With Saudi-hosted talks to end Sudan fighting producing minimal results and Arab states supporting rival forces, de-escalation in the Middle East faces a major test.

So does Gulf states’ ability to employ dollar diplomacy to persuade poorer Arab brethren to align with the policies of countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

In Sudan, the stakes are high.

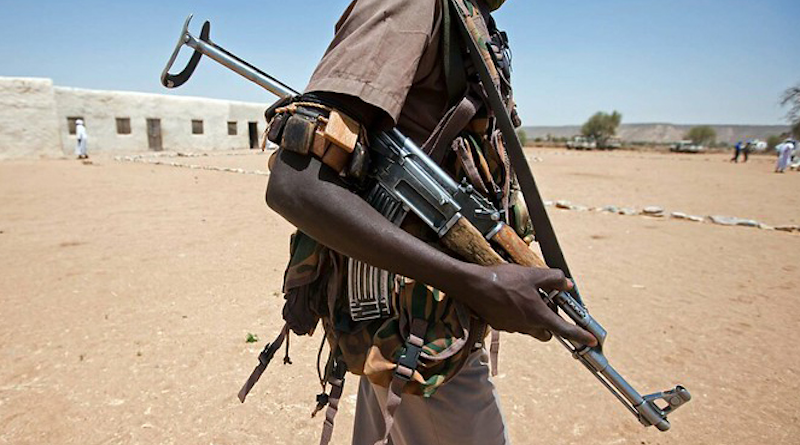

Gulf states fear four weeks of fighting between the Sudanese army headed by Army General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the dissident Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, a.k.a. Hemedti could spark a broader war in the Red Sea that threatens their maritime and strategic interests.

The most US and Saudi mediators were able to achieve in days of talks in the port city of Jeddah between the army and the RSF was “a declaration of commitment to protect the civilians of Sudan” rather than a halt to the fighting.

A US State Department official said the declaration would “guide the conduct of the two forces so that we can get in humanitarian assistance, help begin the restoration of essential services like electricity and water, to arrange for the withdrawal of security forces from hospitals and clinics, and to perform the respectful burial of the dead.”

The World Health Organisation (WHO) last week put the number of killed in the fighting at 604, many of them civilians. It said 51,000 had been wounded and 700,000 displaced.

The mediators hope that they can leverage the declaration to achieve agreement on a 10-day ceasefire to implement it. That in turn, officials said, could create the basis for a longer halt to the fighting.

Officials said implementation of the declaration would be monitored with overhead imagery, satellite data, social media analysis, and on the ground reporting from Sudanese civil society members.

In an indication of the multiple obstacles, the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva narrowly passed a motion tabled by the United States and Britain to increase monitoring of human rights abuses in Sudan.

Arab and African nations either opposed the motion or abstained because of Saudi and Sudanese lobbying against it.

Saudi Arabia asserted that the motion could jeopardise the Jeddah talks while Sudanese ambassador Hassan Hamid Hassan charged that the council was interfering in Sudan’s internal affairs.

“What’s happening in Sudan is an internal affair and what the SAF (Sudanese Armed Forces) are doing is a constitutional duty to all armies in all countries in the world,” Mr. Hassan said.

Progress in the Jeddah talks was hampered by the fact that they are conducted by representatives of the two commanders rather than by Mr. Al-Burhan and Mr. Hemedti themselves.

Signalling that days of talks had not brought the two sides any closer together, the negotiators, the army’s Rear Admiral Mahjoub Bushra Ahmed Rahma and Brigadier General Omer Hamdan Ahmed Hammad, Mr. Hemedti’s brother, did not shake hands after signing the document on humanitarian assistance.

Moreover, with both sides convinced that they have the upper hand, neither has an incentive to implement a long-lasting halt to the fighting. So far, neither the army nor the RSF has abided by several earlier ceasefires.

“A permanent ceasefire isn’t on the table … both sides believe they are capable of winning the battle,” said a Saudi diplomat.

No external player – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt, the United States, and Russia – wants to prolong the conflict even if most of the players backed the army and the RSF in their efforts to stymie a transition to civilian rule after mass anti-government protests toppled President Omar al-Bashir in 2019.

Yet, Egypt, dependent on Gulf financial and economic aid, and the United Arab Emirates have long-standing ties to opposing parties in the Sudanese conflict even though Cairo and Abu Dhabi insist that they have not taken sides.

Cairo’s view of Sudan drives Egyptian support for Mr. Al-Burhan and the Sudanese army as an indispensable ally in its long-running dispute with Ethiopia over the controversial Renaissance Dam.

Egypt has described the giant hydroelectric project on the Blue Nile in northern Ethiopia as an existential threat because of its potential to control the river’s flow, which is vital to life in the country.

The UAE has long worked with Mr. Hemedti, who sent mercenaries to fight in the Saudi-led Yemen and has positioned himself as a bulwark against Islamists who dominated the Al-Bashir government and are believed to be influential in the military.

The UAE also facilitates Mr. Hemedti’s lucrative gold exports through Dubai. At the same time, the UAE has kept its lines open to the army and Mr. Al-Burhan.

Last year, Sudan’s DAL conglomerate signed a US$6 billion agreement, backed by Mr. Al-Burhan, Sudan’s de facto ruler, with two UAE companies, AD Ports and Invictus Investment, to build a port in Abu Amama on the Red Sea. The port would be a key node in an Emirati Red Sea string of strategic outposts.

Last week, Mr. Al-Burhan supporters demanded the expulsion of Emirati diplomats in retaliation for the UAE’s backing of Mr. Hemedti, the general’s rival.

Arab media reported that the UAE, amid fears of a breakdown of the Jeddah talks and an escalation in the fighting, has sought to financially entice Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to back away from his support for Mr. Al-Burhan.

Grappling with economic turmoil that has seen official inflation shoot up to nearly 34 percent and the local currency halve in value over the past year, Mr. Al-Sisi last month visited the UAE in search of new funding, days before the Sudan fighting erupted.

The UAE’s effort to reportedly buy off Egyptian support for Mr. Al-Burhan would backtrack on its recent shift from unconditional support to demanding economic reform and enhanced transparency in return for its generosity.

The effort also harks back to when Gulf states poured money into economic black holes in exchange for loyalty.

With the Renaissance Dam in mind, that may be, for Egypt, a high price to pay.

Generational change further complicates Egypt’s relations with the UAE and other Gulf states.

Ziad Bahaa-Eldin, Egypt’s first deputy prime minister after the 2013 UAE and Saudi-backed military coup, noted that generational change had produced Gulf leaders without emotional ties to Egypt. They no longer see Egypt, the Arab world’s most populous nation, as the region’s strategic, cultural, and educational pulse, Mr. Bahaa-Eldin said.

The coup that toppled Mohammed Morsi, a leader of the Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt’s first and only democratically elected president, and brought Mr. Bahaa-Eldin to office, may have been the transition point.

An octogenarian, 88-year-old King Abdullah, ruled Saudi Arabia at the time. Admittedly, then Emirati crown prince Mohammed bin Zayed, the UAE’s de facto ruler, who has since become president, was at 52 considerably younger. He fits Mr. Bahaa-Eldin’s mould.

“We are in the presence of a new generation of officials and decision-makers who do not have the emotional relationship with Egypt that exited with the generation that preceded them and that was raised and educated in Egypt,” Mr. Bahaa-Eldin said.

“As much as we need the Arab countries due to the retreat of our economy and the fact that we are witnessing a crisis, the Gulf also still needs Egypt, which is a force to be reckoned with, is still the source of culture, education, and medicine, and has strategic political weight in the region,” Mr. Bahaa-Eldin added.

Mr. Al-Sisi is betting on that in his refusal to toe the UAE’s line in Sudan.