Al-Shabaab, the wealthiest and most lethal affiliate of al-Qa`ida, has been wreaking havoc in the East African region since 2006. Its continued resilience, even in the face of mounting counterinsurgency efforts, is underpinned by its sophisticated communications architecture. Within this communications architecture lies a highly disciplined social media strategy, exposing the group’s technical competency, and the importance afforded to strengthening this online frontline by al-Shabaab. This article will present findings from the author’s first-hand monitoring of al-Shabaab’s social media activity, evidencing the controlled, adaptive, and coordinated approach the terrorist group takes to its online behavior. To effectively address al-Shabaab’s continued resilience and influence in the region, the counterinsurgency effort must understand the vital importance and integrated nature of the group’s online operations within its overall strategy.

Even before the Islamic State built its ‘virtual caliphate,’ the Somali terrorist group Harakat al-Shabaab al-Mujahideen, more commonly known as al-Shabaab, was live-tweeting updates from its 2013 Westgate Mall attack in Nairobi.1 Ten years on, the group continues to operate at the cutting edge of the digital landscape, implementing a deliberate online strategy that demonstrates its ability to quickly understand, leverage, and ultimately weaponize new social media platforms and technologies. This article will present findings from a research study into al-Shabaab’s online behavior between January and December 2023, and explore the concerning threats posed by al-Shabaab’s growing technical skills.

Al-Shabaab is the wealthiest and most lethal affiliate of al-Qa`ida.2 Born out of its role as the youth militia of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) in Somalia, al-Shabaab emerged as an established jihadi terrorist organization following Ethiopia’s invasion of Somalia in 2006.3 Its success in the region relies heavily on al-Shabaab’s ability to present itself as a viable alternative to the ‘apostate’ government of Somalia, both by acting as a de facto, albeit ruthless, authority in the areas it controls, as well as through its powerful propaganda.

In 2022, following the election of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) declared ‘total war’ on al-Shabaab,4 and has promised to eradicate the terrorist group by 2024.5 The first phase of the counter-offensive did at first make significant gains against al-Shabaab.6 However, despite regional and international support for the war, al-Shabaab has proven itself remarkably resilient, as it has for nearly two decades. Since early 2023, the group has recaptured portions of the territory lost in the first phase of the counter-offensive, and continues to raise significant funds, maintain strong weapon caches (including weapons stolen from the Somali National Army), and draw in new recruits from Somalia and the wider East Africa region.7

Al-Shabaab’s continued physical strength and resilience in the region is enhanced by its sophisticated communications infrastructure.8 Well-produced, timely, and relevant propaganda from numerous al-Shabaab-affiliated entities reaches audiences from rural Somalia to the streets of London. The combination of established communication infrastructure and ongoing communication campaigns allows the group to maintain a level of influence through its established brand.9 It plays into a narrative that al-Shabaab offers a credible alternative to the current government—providing ‘legitimate,’ timely news to Somalis both at home and abroad.10

Within this sophisticated communication infrastructure sits a deliberate social media strategy, one that is of paramount importance to the group but remains largely unrecognized by the counter-al-Shabaab effort. Detailed observation of al-Shabaab’s online behavior from January to December 2023 suggests that the group takes a tactical approach to building its network online, controlling the narrative, and adapting its approach in response to a rapidly evolving social media ecosystem. Such a deliberate, agile, and effective strategy indicates that al-Shabaab’s online presence is anchored by a centralized structure and supported by technology-based solutions to effectively control and coordinate its online activity. Importantly, al-Shabaab is prioritizing these skills within the context of a wider technological revolution, where access to and affordability of emerging technologies such as large language models (LLMs) and artificial intelligence (AI) will fundamentally alter how wars are fought.11 Al-Shabaab is very likely placing an increasing importance on growing technical skills to leverage these emerging technologies for operational use on social media and beyond.

This article will first provide a brief overview of al-Shabaab’s overall communication architecture, which includes the group’s social media strategy. Next, the article will present findings from the author’s first-hand monitoring of key al-Shabaab-affiliated accounts across Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), and YouTube between January and December 2023. As accounts would go offline frequently, the number of accounts monitored at any one time varied, but over the course of the study, more than 250 Telegram channels and over 190 Facebook accounts were identified. This section will outline the author’s understanding of al-Shabaab’s social media strategy, exploring how the group controls its narrative, adapts to evolving social media moderation techniques, and coordinates its approach across platforms to ultimately weaponize online spaces. Finally, the article will offer considerations on how technological advances will continue to diminish the distinction between the real and digital worlds, making it vital for the counter-al-Shabaab effort to tackle the terrorist threat in its entirety, both on the ground and online.

Al-Shabaab’s Communication Architecture

Since its formation, al-Shabaab has placed heavy strategic importance on communication.12 The group’s communication architecture consists of four key components:

- Al-Kataib Media Foundation, which produces al-Shabaab’s official audiovisual content, including its photo and video releases. Content produced by al-Kataib is then distributed on al-Shabaab-affiliated online news sites and social media accounts.13

- Radio stations, which target Somali-based audiences, and provide al-Shabaab-affiliated content to rural locations that might not have access to the internet.a Affiliated stations include al-Furqan and al-Andulas.14

- Online news sources, which masquerade as legitimate news outlets through online sites, and include agencies such as Shahada News, Somalimemo, and Calamada. They produce pro-insurgent articles, as well as report on relevant issues of wider Somali, regional, and global concern to project a veneer of legitimate journalism.15

- Social media networks and messaging apps, which span an array of popular and decentralized platforms to distribute al-Shabaab propaganda. The group currently prioritizes Telegram and Facebook, with a growing use of the Russian social network known as OK.ru, as well as TikTok, X, and YouTube.

Al-Shabaab displays a strong coherence of messaging across its media sources. The group understands the power of consistent, repetitive messaging. Tightly knit coordination of messaging results in a surround-sound of al-Shabaab narrative, repeated across multiple sources and platforms, meant to reinforce the ‘veracity’ of its message. Such coherence helps to portray al-Shabaab as a credible alternative to the current government—providing ‘trusted’ news to its audience.16

The Somali government has attempted to take steps to curb the influence of the group’s propaganda as part of its ongoing counter-offensive, warning Somali news outlets in 2022 that publishing al-Shabaab’s content, even for journalistic purposes, would be considered a criminal offense.17 More recently, in August 2023, the government banned Telegram and TikTok, citing al-Shabaab’s use of the platforms for its recruitment and operations.18 However, attempts to dampen al-Shabaab’s communication infrastructure by the Somali government have been largely short-sighted. The recent Telegram and TikTok ban have had little impact on al-Shabaab’s online networks or ability to communicate on these platforms, and primarily served to further embolden the group’s narratives about government ‘censorship.’ The ban’s limited impact can be credited, at least in part, to growing levels of sophistication behind al-Shabaab’s online strategy.

Al-Shabaab’s Online Strategy

In the decade since al-Shabaab first live-tweeted the 2013 Westgate attack,b it has increasingly tightened its grip on social media. Back in 2014, scholar Ken Menkhaus argued that al-Shabaab’s online presence could serve as a ‘double-edged sword’ for the group, citing instances of rogue messengers and heated disputes among al-Shabaab leadership that played out on the open web.19 Such instances suggested that al-Shabaab did not have sufficient control over its online networks at the time, and that this lack of control could undermine the group’s legitimacy.

Since 2014, social media platforms have proliferated in ways never imaginable a decade ago. This type of proliferation could have resulted in al-Shabaab losing complete control over its narrative within the online space. However, the opposite has played out. From first-hand observation of al-Shabaab’s online networks between January and December 2023, what emerges is an alarmingly well-controlled, adaptive, and coordinated approach to social media that serves to weaponize online spaces and platforms.

Controlling the Narrative

Al-Shabaab’s online presence appears remarkably centralized. Centralization requires high levels of discipline and oversight to ensure its agents stay ‘on message,’ and that discursive or dissentive narratives are seen by followers as outliers. It also requires high levels of technical competency within the organization, to ensure that its selected messengers operate in ways that take advantage of social media’s algorithms, avoid moderation tactics by the platforms, and leverage emerging technology in support of its overall strategy.

Al-Shabaab does display these high levels of discipline within its online ranks. Nearly word-for-word messages are repeated across hundreds of al-Shabaab-affiliated Facebook and Telegram accounts on a daily basis. To do so, the group implements what appears to be a methodical approach to network building to ensure managed growth and control over its messengers.

The group’s approach hinges on the use of a small group of trusted, core ‘opinion setters.’ The legitimacy that these opinion setter accounts carry within al-Shabaab’s online networks is critical for maintaining control over the group’s messaging. These online opinion setters appear to have significant license for developing their own content and sharing their opinions across platforms—namely Facebook and Telegram, the two most utilized platforms by the group. Their style is journalistic, reinforcing the legitimacy of their content, though with a clear pro-al-Shabaab agenda. They also frequently serve as the first source of information on major attacks, posting live updates within minutes of guns being fired, often before other al-Shabaab-affiliated media sources report on the battle.20

The opinion setters’ role therefore is one of control. The content that they generate becomes the standard bearer for al-Shabaab-affiliated networks, thereby reducing the authenticity of potential rogue messaging that comes from outside sources. This study has identified approximately seven to 10 active core opinion setter personas, who maintain multiple accounts across Facebook, Telegram, and to a lesser extent, TikTok, X, and YouTube. As the sections below will detail, these accounts appear to closely coordinate to share information and maintain their networks, even in the face of improving social media moderation tactics.

A larger group of ‘amplifier’ accounts form a second level of al-Shabaab’s online network, which serve to promote the name and brand of core opinion setters. They do not have the same license to generate their own content or share their own opinions; they primarily exist to amplify content originating from the opinion setters’ accounts through reposts and forwards. This approach signals to the wider network that certain names are synonymous with al-Shabaab.

Amplifier accounts also push content out to wider audiences, both those that are already sympathetic to, but possibly not yet actively a part of al-Shabaab, as well as those that are vulnerable to the grievances that al-Shabaab manipulates for recruitment (‘at-risk’ accounts). Amplifier accounts build larger networks and ‘friend’ wider audiences in support of this outreach. They also engage more actively with their online networks than do opinion setters. Core opinion setters, on the other hand, appear to guard their networks more closely, to limit their exposure and risk of being taken offline.

Strategically, amplifier accounts also engage with anti-al-Shabaab sentiment. While this might seem counterintuitive to its modus operandi of maintaining complete control over the narrative, al-Shabaab also displays a solid understanding of how social media algorithms work. Facebook’s algorithms, for example, promote content with high levels of engagement. Regardless of whether that engagement is pro- or anti-al-Shabaab, the result is the same: Engaged content is pushed to the top of news feeds and shared with expanded networks. The group therefore does not actively discourage dissension within its networks, as such amplification is good for outreach. Instead, to ensure that anti-al-Shabaab sentiment does not fracture the group’s unified front, amplifier accounts troll anti-al-Shabaab posts, using consistent pro-al-Shabaab narratives, which they frequently complement with supporting al-Kataib photographic ‘evidence.’

The use of opinion setters is unique to al-Shabaab, at least among other terrorist groups operating in East Africa. Their use demonstrates al-Shabaab’s technical understanding of the social media landscape. As Menkhaus noted, the potential for social media to spiral out of control was high for the group and threatened to expedite the fracturing of al-Shabaab’s narrative.21 But by using opinion setter and amplifier accounts, the group has, so far, managed to reduce the threat of splintered narratives, while also harnessing the power of social media’s amplification and networking algorithms.

Adaptability to an Evolving Online Environment

While Somali is not a priority language for social media giants such as Facebook or Telegram, these platforms have nonetheless made significant strides to identify al-Shabaab networks and remove its content and accounts. In the face of advancing moderation from these sites, al-Shabaab’s ability to quickly adapt and maneuver around these evolving tactics is all the more impressive.

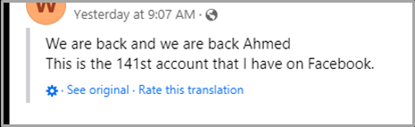

Al-Shabaab has grown accustomed to its accounts being removed from social media platforms, referred to as “takedowns.” Opinion setters gloat about how often their accounts are taken down—seen as a badge of honor by those in the network.

However, the rapidity with which al-Shabaab-affiliated accounts can create new accounts and reconnect those accounts to the wider al-Shabaab online network should be cause for concern. Figure 2 shows an opinion setter bragging about his 141st account, for example. Between June and early September 2023, this same prominent opinion setter cycled through at least 17 new Facebook accounts affiliated with his persona. Over a one-month period, the same opinion setter created at least 11 new Telegram accounts. New accounts on both platforms were often created within a day of a previous account being banned, nullifying the impact of these takedown efforts.22

Account creation on many platforms and messaging apps requires a unique email address and/or phone number. While relatively straightforward to generate additional email addresses, repeatedly registering accounts with a new phone number, as is required by Telegram for example, necessitates access to multiple SIM cards or devices, a level of technical knowledge on how to generate fake numbers and/or privileged access into mobile network providers.

Frequently, new accounts are generated within hours of old accounts being banned. This speed suggests that: 1) al-Shabaab facilitates the creation of multiple back-up accounts for key accounts across priority platforms; and 2) al-Shabaab facilitates the registration of new accounts to replace banned accounts through access to new devices, SIM cards, and/or fake phone numbers. Any of these scenarios highlights the concerning level of resources and overall technical competency that exist within al-Shabaab to ensure that its online presence is maintained.

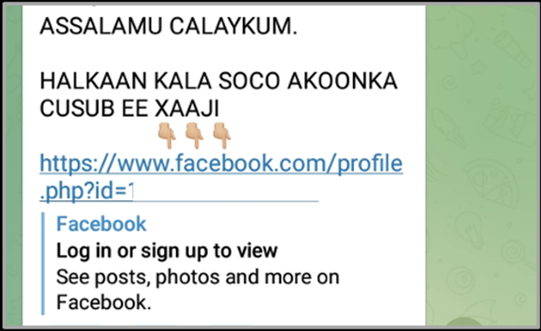

Al-Shabaab has also demonstrated an impressive ability to limit the impact of large takedown efforts through its approach to parallel network creation. Affiliated accounts replicate themselves across multiple platforms, generating content on multiple accounts on each platform. Importantly, opinion setter and amplifier accounts use very similar displays—similar handle names, profile pictures, and content signatures—to mark their accounts so that followers within the network can easily find and follow them. They ask followers to join them on multiple platforms, to ensure that parallel networks exist across the likes of Facebook, Telegram, TikTok, and X. This approach means that if an account is banned from Facebook, for instance, a new account can be created and shared by a parallel al-Shabaab network on Telegram, thereby rebuilding the account’s network on Facebook within hours, rather than days or weeks. A slight but notable decline in this practice has been observed since September, however, due to considerable efforts made by Facebook to remove opinion setter accounts from the platform more permanently.

Equally, al-Shabaab’s appetite for exploring fringe platforms or decentralizedc social networks has grown in response to advancing moderation tactics. Expanding the platforms al-Shabaab operates on does pose a risk to the group, as the wider its network, the harder it becomes to maintain control over its narratives. That said, platforms such as the Russian social network site Odnoklassniki, abbreviated as OK.ru, have become important distribution channels for al-Shabaab, as OK.ru’s moderation is relatively minimal. In typical al-Shabaab fashion, however, its expansion into these new sites appears carefully controlled and managed, suggesting the group places restrictions on any unauthorized use of new platforms.

Al-Shabaab’s approaches to new account generation, parallel network creation, and expansion into alternative platforms appear deliberate and coordinated, and emphasize the group’s growing technical knowledge. Core opinion setters have acknowledged that al-Shabaab has taught them techniques for avoiding moderation and strengthening their networks (see Figure 4). Al-Shabaab’s ability to anticipate and limit the impact of rapidly improving and evolving moderation tactics on certain social media platforms suggests that it too is investing in its own improving and evolving technical capabilities.

Between September and December 2023, however, Facebook appears to have made a concerted effort to remove opinion setter accounts more permanently. While al-Shabaab’s network on Facebook remains large and diverse, the unified narrative seen on the platform in the first eight months of 2023 is declining, given the reduced number of core opinion setters consistently operating on Facebook since September. Telegram, on the other hand, continues to offer a more cohesive narrative from al-Shabaab, and opinion setters remain active on the platform.

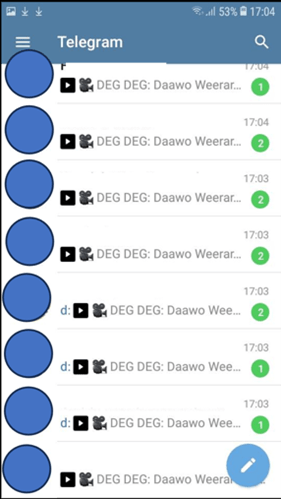

Coordinated Information Sharing and Responses

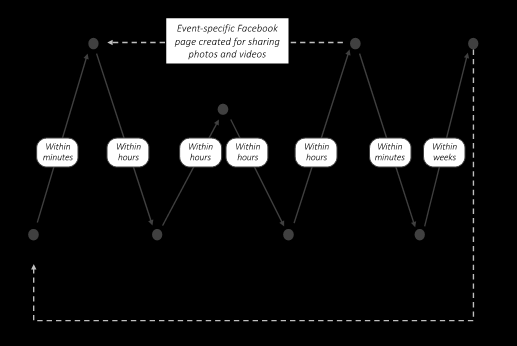

Al-Shabaab’s online behavior suggests that strong, behind the scenes coordination exists between opinion setter accounts, amplifier accounts, and al-Shabaab’s wider communication structure. For example, on September 27, 2023, al-Kataib released a three-minute video of a recent attack in an area of Somalia called Nuur Dugle. Within one minute of its release, 13 al-Shabaab-affiliated Telegram channels shared the video, alongside the same message. This coordination resulted in over 5,000 subscribers receiving the video on Telegram within minutes of its release. The video also appeared on an event-specific Facebook page and OK.ru at the same time.

Al-Shabaab also maintains consistency of this narrative across its various media sources, including radio and web-based media outlets. The speed with which the narratives spread from one social media platform to another, then to radio and to news agencies, suggests high levels of coordination across the group’s communications infrastructure. Specifically when reporting on a significant attack, al-Shabaab frequently follows a predictable pattern of sharing information from one platform to the next, within a tight time-frame, as seen in Figure 6. The flow of messaging around key attacks highlights the coordination of messaging, and the centrality of Telegram as the often first source of information on major attacks.

Finally, al-Shabaab’s formidable response to the Somali government’s August 2023 Telegram ban exposes a closely coordinated effort across the group’s social media networks. Within a day of the ban being announced, al-Shabaab networks circulated detailed instructions for accessing Telegram through virtual private networks (VPNs) and custom proxy servers. Opinion setter accounts also promoted WhatsApp networks as fallback options for providing similar services to Telegram, and reinforced the importance of its Facebook network. Taunting the government for its ban, al-Shabaab flooded Telegram with new accounts and even more content, and used the ban to spin narratives about the government’s supposed censorship, lies, and weakness to enforce such a ban.

Al-Shabaab also shifted how it operated on the platform. Prior to the ban, key Telegram accounts would remain active for months, despite the extremist nature of the content. Directly after the ban, certain accounts were being removed daily.d In response, opinion setters took to generating and promoting multiple new accounts at once. To protect these new accounts from takedowns, they have frequently changed the handle names and have alternated between making their accounts public and private. Doing so creates significant challenges for Telegram moderators to keep their fingers on the pulse of the network and it is likely a deliberate, and well-informed strategy by al-Shabaab to avoid significant consequences from the platform ban (again, see Figure 4). This tactic has paid dividends for al-Shabaab, with the rate of account takedowns on Telegram slowing in the final three months of 2023. For example, one prominent opinion setter cycled through 15 Telegram channels between August 15 and the end of September, but since early October, the same opinion setter has maintained one active account.

The Integrated Nature of al-Shabaab’s Digital and Real-World Threats

Monitoring al-Shabaab’s online behavior between January and December 2023, it is evident that the group operates a highly controlled communications infrastructure and implements a methodical and well-informed online strategy. Affiliated social media accounts are not just dispersed supporters promoting the group’s ideology; opinion setters and amplifier accounts are tactical agents responsible for manning an online frontline, supported by al-Shabaab’s overall communication infrastructure. This online frontline, and the actors who lead it, form a core component of al-Shabaab’s overall strategy; one that should be carefully considered by the counter-al-Shabaab effort. While the nature of the group’s online operations will continue to evolve rapidly in response to changing moderation tactics and advancements in technology, what will remain constant is al-Shabaab’s commitment to its online presence.

These online agents are also backed by growing technical competencies within al-Shabaab. The consistency and velocity of messaging, agile responses to enhancing moderation tactics, and overall strategic approach to weaponizing social media requires technological tools, capabilities, and know-how. The war being waged by al-Shabaab is therefore no longer exclusive to its ground operations; alongside its physical attacks, al-Shabaab simultaneously seeks to advance its online frontline, investing in the tools needed to wield its strength militarily and online, through increasingly integrated operations. Within minutes of guns being fired, opinion setters are sharing real-time updates and al-Shabaab claims on Telegram,23 meaning that physical battles are playing out alongside a digital war of influence.

Al-Shabaab’s messaging on the war in Gaza presents a prime example of how its online influence impacts its real-world operations. Since October 7, al-Shabaab has used its online networks to bring what would be a Middle East conflict into the East African context, drawing parallels between Hamas’ and al-Shabaab’s supposedly anti-colonial struggles and what is presented as the oppression faced by Muslims in Gaza and Somalia. The pro-Hamas and pro-Palestinian content promoted by al-Shabaab online presents the group with a unique opportunity to strengthen its ground operations. Using real-time ‘evidence’ of Muslim oppression coming out of Gaza to reinforce its narratives online, al-Shabaab is widening its appeal on-the-ground and enlarging its recruitment base to a more international audience aggrieved by the situation in Gaza.24 In an increasingly digital world, it is no longer possible (or wise) to separate online from offline extremism. They become two sides of the same coin.

Critical to the success, therefore, of the counter-al-Shabaab effort is a recognition of the integrated nature of al-Shabaab’s social media presence and its ground operations, and an understanding of how the group’s technical competencies will continue to change the trajectory of the group’s operations. Doing so necessitates greater collaboration across regional security actors and technology experts, to develop more detailed predictions of when and how the group’s capabilities will collide with growing access to emerging technologies, and to monitor the group’s online evolution. It is time to move away from reactive measures to this online frontline, which prioritize content moderation and counter-narratives. They have very little impact on dislodging al-Shabaab’s social media network or degrading the group’s overall influence. Coming to terms quickly with the inevitability of al-Shabaab’s growing social media presence and enhancement of its technical skills will allow the counter-al-Shabaab effort to better understand the nature of this evolving threat, develop more comprehensive security strategies, and consider opportunities for using emerging technology proactively in the fight against al-Shabaab.

Substantive Notes

[a] Radio stations also have online sites and social media accounts to share their content internationally.

[b] In September 2013, al-Shabaab gunmen invaded a popular Nairobi mall in retaliation for Kenya’s involvement in the Somali conflict. The siege lasted for over three days and saw dozens of civilians killed.

[c] Decentralized social networks run on independent servers, rather than on a centralized server.

[d] It is very difficult to know by whom. Telegram is notoriously private and has not provided public detail on its approach to content moderation specific to Somalia, or any possible collaboration with the Somali government.

Citations

[1] David Mair, “#Westgate: A Case Study: How al-Shabaab used Twitter during an Ongoing Attack,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40:1 (2016): pp. 24-43.

[2] Stig Jarle Hansen, “Can Somalia’s New Offensive Defeat al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 16:1 (2023).

[3] Claire Klobucista, Jonathan Masters, and Mohammed Aly, “Backgrounder: Al Shabaab,” Council on Foreign Relations, December 2022.

[4] Mohamed Dhaysane, “Somalia’s President Vows ‘Total War’ Against al-Shabab,” Voice of America, August 24, 2022.

[5] “PM: Over 45% of al-Shabaab strongholds liberated in Somalia,” Garowe Online, September 24, 2023.

[6] “Sustaining Gains in Somalia’s Offensive against Al-Shabaab,” International Crisis Group, March 2023.

[7] See James Barnett, “Faltering Lion: Analyzing Progress and Setbacks in Somalia’s War against al-Shabaab,” Hudson Institute, September 2023 and Mohamed Gabobe, “As foreign troops withdraw, how likely is an Al-Shabab takeover in Somalia?” New Arab, September 2023.

[8] Alta Grobbelaar, “Media and Terrorism in Africa: Al-Shabaab’s Evolution from Militant Group to Media Mogul,” Insight on Africa 15:1 (2023): pp. 7-22.

[9] Matt Freear, “How East Africa’s Terrorists Build Their Brand Strength,” RUSI Newsbrief 32:2 (2019).

[10] Christopher Anzalone, “Continuity and Change: The Evolution and Resilience of Al-Shabab’s Media Insurgency, 2006–2016,” Hate Speech International, November 2016.

[11] David E. Sanger, “The Next Fear on A.I.: Hollywood’s Killer Robots Become the Military’s Tools,” New York Times, May 2023.

[12] Mary Harper, “Is Anybody Listening? Al-Shabaab’s Communications” in Michael Keating and Matt Waldman eds., War and Peace in Somalia: National Grievances, Local Conflict and Al-Shabaab (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[13] Anzalone.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Somalia Warns Media Not to Publish Al-Shabab Propaganda,” Voice of America, October 2022.

[18] “Somalia bans TikTok, Telegram and 1XBet over ‘horrific’ content, misinformation,” Reuters, August 2023.

[19] Ken Menkhaus, “Al-Shabaab and Social Media: A Double-Edged Sword,” Brown Journal of World Affairs 20:2 (2014): pp. 309-327.

[20] Georgia Gilroy, “Fanboys or the Frontline?: How al-Shabaab’s Social Media Influencers are Controlling the Narrative,” GNET, July 2023.

[21] Menkhaus.

[22] As identified by author’s monitoring of al-Shabaab online networks throughout 2023.

[23] See Paul Cruickshank, “A View from the CT Foxhole: Harun Maruf, Senior Editor, Voice of America Somali,” CTC Sentinel 15:11 (2022) and Gilroy, “Fanboys or the Frontline?”

[24] Georgia Gilroy, “How al-Shabaab is Using Social Media to Build a Bridge between Gaza and Somalia,” GNET, October 2023.