“China did this,” “the Chinese did that.” There is an essentialization of China and Chinese actors that hinders our understanding of China-Africa relations – whether to praise or demonize them – as it lumps a multiplicity of approaches, as well as actors, into a fantasized strategy. Hence, the need to use the plural to talk about these Chinese presences in Africa.

Chinese Actors in Africa

To begin with, there are institutional actors who may clash within the embassies themselves. There are divergences between officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who subordinate the commercial to the political, and those from the Ministry of Trade who, conversely, subordinate the political to the commercial. This disagreement was particularly sensitive after the institutional reform of 2003 which, in fact, granted a certain pre-eminence to the Ministry of Trade over that of Foreign Affairs. This rivalry between the commercial and the political is also reflected in the relationship between officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the ExIm Bank of China, which is under the Ministry of Finance: the former encourages the granting of loans at subsidized rates, while the latter prefers to grant loans at commercial rates. These frictions in Africa can be expressed through political confrontation – and thus opposing strategies – at the central government level in China. These institutional disputes may become even more important as the National Development and Reform Commission depends on piecemeal information from institutional actors, or even the inevitably biased information provided by recipient companies.

Chinese companies and their strategies, which are as diverse as they are varied, depend as much on their status as on their search for markets, without us being able to reduce them to the observation of a grand plan, except for a certain desire to internationalize (zhouchuqu) as encouraged by the Chinese government. It should be noted that this internationalization does not automatically make these companies multinationals or globalized companies insofar as the turnover they achieve abroad remains marginal in their total turnover. Among the large state-owned enterprises under the direct supervision of the central government, a distinction can be made between those that are effectively mandated by the Chinese government to guarantee the supply of raw materials and those that are market-seeking, such as the large construction companies that have no other objective than to make profits. Then there are the provincial state-owned enterprises whose primary loyalty is to local governments, which strengthen their power through the profits they make.

There are also large private or supposedly private companies such as Huawei which, in the early 2000s, opposed the Chinese government’s desire to impose purely Chinese telephone standards for the sale of telephone equipment abroad. Certainly, in the current situation, marked by the Sino-American economic war and the intransigent authoritarianism of the Chinese Communist Party, it is not certain that companies like Huawei can still enjoy such great decision-making autonomy, as shown by the recent setbacks of Jack Ma (former CEO and founder of Alibaba). Private SMEs are potentially free electrons. Think of the Haite company, which had a project to set up a special economic zone in Tangiers, but which, despite the initial support of the Banque marocaine du commerce extérieur (future Bank of Africa), failed to receive the support of Beijing.

The Chinese authorities put the number of Chinese companies active in Africa at between three and four thousand. The difference with the number stated by the 2017 McKinsey report (10,000 Chinese companies in Africa) results from a confusion. The companies mentioned above are Chinese companies (or their subsidiaries) under Chinese law – and therefore incorporated in China – whereas the McKinsey report also includes small private companies under local African law (and therefore legally and statistically non-Chinese) run by Chinese nationals whose allegiance to Beijing may be inversely proportional to the autonomy they enjoy.

China-Africa Economic Relations in Review

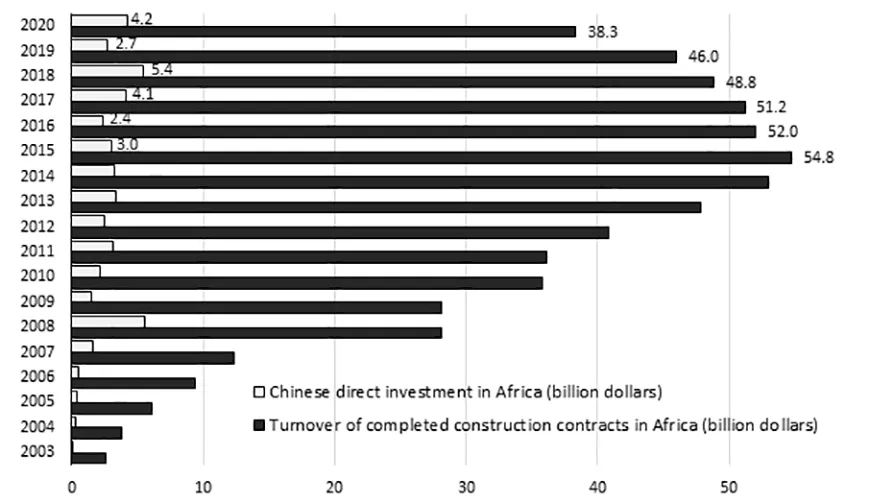

Analysis of Chinese statistical data, as well as that of international institutions, clearly shows that Chinese companies in Africa do not act specifically as investors, contrary to the oft-repeated cliché. They act as service providers, customers and suppliers of goods. The amount of these commercial activities (services and goods) is on average 80 times higher than the amount actually invested in Africa. For instance, in 2019, the amount of Chinese direct investment in Africa was $2.7 billion, which is roughly the value of Dong Feng’s stake in the French car manufacturer Peugeot (PSA): that is, the same amount for, on the one hand, a single Chinese company investing in a single foreign company, and on the other hand, a significant number of Chinese companies investing in the 54 African countries.

These figures reveal the classic confusion between investing, financing, and providing services. International bodies (IMF, OECD) have given a clear definition of what should be considered as investment. It is a definition that China adheres to and is recalled each year in MOFCOM’s statistical communiqué on Chinese direct investment abroad. In order to make the confusion more obvious and to give investment its correct role, it is useful to compare, in Figure 1, the amount of investment with the services provided (the indicator for which is the turnover of overseas construction contracts completed in the same year).

According to Figure 1, in recent years, the turnover of Chinese construction companies was more than ten to twenty times the amount invested by China in Africa. This reveals an inescapable fact: Chinese investment in Africa is an expense for China, not an income for the host African country. In contrast, payment for services is an expense (as well as an investment) for the African client country, but an income for China. Given these differences, these two activities each illustrate China’s presence in Africa in their own way. They clearly show that China is a service provider rather than an investor, and that Africa is a client rather than a partner.

The consequence of China’s low investment in Africa is that China is only marginally involved in its industrialization. Globally, China’s industrial investments abroad represent only 19.6% of its foreign investments and are mostly in Western countries in search of both technology and profits. In Africa, Chinese industrial investments are made in labor-intensive activities, which are therefore hardly capital-intensive and consequently do not industrialize much and involve only very limited technology transfers. The 14th Five-Year Plan (published on 13 March 2021), referring to concerns over anticipated deindustrialization in China, therefore invites economic actors to consolidate the industrial sector. This is a reaffirmation of a principle stated in 2015: “let the manufacturing sector strengthen the nation” (zhizao qiang guo). This orientation is, moreover, consistent with a declared commitment to the rapid robotization of labor-intensive activities, leading in particular to the interruption of any re-importing delocalization. Cooperation with Germany on the fourth industrial revolution can also be explained by this concern for a “robotic revolution” (jiqiren geming) made a priority by Xi Jinping in 2014, because not only will it raise the productivity of workers who would otherwise have been rendered uncompetitive by very high wages, but it will also make it possible to ignore the demographic challenge of a population that is ageing too quickly because it has not given birth to a younger generation that is numerically large enough to justify a consumption-driven economy. So, it is not surprising that there is now little mention of exporting industrial production capacity and the subsequent creation of 85 million jobs outside China – which would require, according to MOFCOM’s 2018 figures, 1.3 million Chinese companies to internationalize given the small number of jobs they create. The trade war between China and the United States also reinforces a refocusing announced in July 2020 which goes in the same direction: this so-called “dual circulation” (shuang xunhuan) strategy can only increase China’s autonomy, thus giving the impression of an economic confinement, or even a withdrawal into itself in a political context which is relatively unfavorable for it.

Thus, much ado about investment. Chinese companies invest only marginally in Africa. Instead, they trade and build infrastructure on behalf of African governments, which invest in infrastructure with Chinese funding (see Figure 2). This raises questions about the status of African countries in the New Silk Roads strategy.

Both the inland and maritime Silk Roads are a legacy of the traditional trade routes between Asia and Europe. The maritime route in its present form was born in the 19th century. It is the successor to the porcelain route used by Arab and Indian merchants. It was then extended to the Mediterranean, and then beyond, to Northern Europe, thanks to the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. One of the first promoters of the modern maritime route is the forerunner of today’s CMA-CGM, which was behind the creation of Djibouti (1888) and the Djibouti-Addis Ababa railway (1897). Since the Asian crisis of 1998, and especially since the early 2000s, Chinese officials have tried, with very limited success, to reform the economic model inherited from Deng Xiaoping. They have tried to transform the engine of their economy, i.e. to substitute growth driven by the domestic market for growth driven by external markets. Hence Xi Jinping’s call in Davos in 2017 for liberal globalization, which can almost be interpreted as a distress call. The New Silk Roads strategy is therefore an initiative to better penetrate European markets (mainly the European Union). Indeed, these are the first outlet for Chinese products, ahead of the countries of Southeast Asia and the United States.

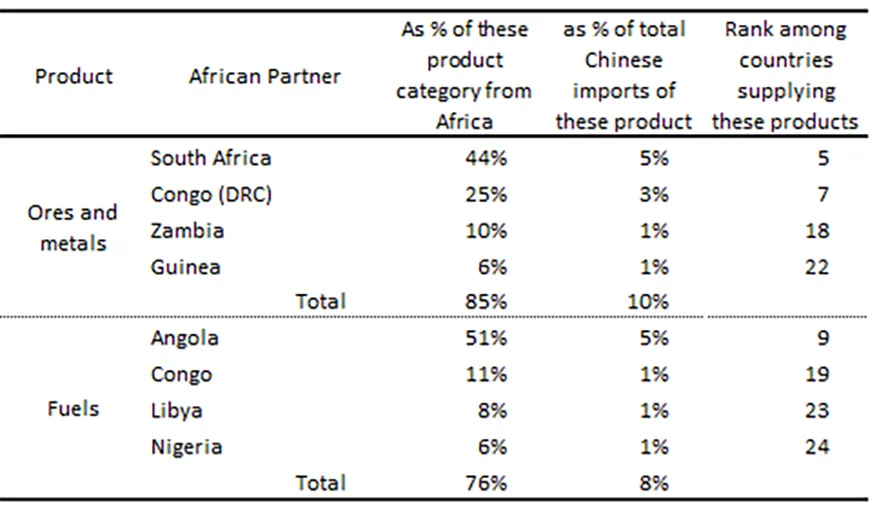

Trade in containerized goods between China and Europe accounts for 15% of Chinese trade year on year (94% of which is by sea) while trade with Africa accounts for only 4%. In fact, all modes of transport combined (sea, air and land), Africa accounts for only 3% of world trade and 3% of Chinese trade in goods. Thus, from a micro-economic point of view (that of Chinese companies), this might offer some potentially large markets. However, from a macro-economic point of view (that of the Chinese nation), this is far from the case. Even in terms of access to raw materials, Africa is very dependent on Chinese purchases. China, on the other hand, has built up a wide range of alternative suppliers for these same raw materials. So, it will never be really dependent on Africa.

Table 1 illustrates this by looking at exports of ores and metals and fuels. Only South Africa and Angola could possibly claim to play a significant role, given China’s very relative dependence on them. Indeed, recent developments in Australia-China relations show that China is not afraid to challenge its supposed dependence on Australia for iron supplies – which in this case could be to the benefit (in the short term at least) of some African countries such as Guinea. Here again, the 14th Five-Year Plan clearly reiterates the will to establish industrial chains that respect the principle of “China first” (yi wo wei zhu). In the context of an unequal international division of labor, this principle only strengthens Africa’s role as a supplier of raw materials alongside other “resource countries” (ziyuan guo).

The lesson we can learn from this is there is a substantial asymmetry in the relationship between Africa as a continent and China as a nation. While China is economically important to Africa, Africa is not important to China. In contrast, African countries are politically important to China.

Africa’s Political Significance for China

To understand the political importance of Africa for China, it is necessary to delve into the history of the late 20th century. In 1989, after the Tiananmen Square massacres, Western countries imposed sanctions on China. This was an electroshock for the Chinese leaders of the time, as evidenced by the Short History of the Chinese Communist Party in a revised version published in 2021 to celebrate its CCP’s centenary. From then on, a dual narrative was gradually established: a fairly liberal economic message illustrated, for example, by Xi Jinping’s speech in Davos (see above); and a vehemently anti-Western political message that has been consolidated over time and has blossomed in recent years, as shown most recently by the rhetoric of certain Chinese diplomats now described as “war wolves.” Politically, this has been translated since the early 1990s into an instrumentalization of the old national humiliation theme and a revision of history textbooks, a reinvention of Confucianism, a reactivation of Third Worldism, and a deepening of ties with developing countries, starting with African countries. Africa has 54 countries with one vote each in the UN General Assembly (except for Eswatini, 53 countries currently recognize Beijing) – that is, almost a third of the votes that can pass decisions. This has led to a rewriting of history, as evidenced by the publication in 1999 of a book tracing fifty years of Chinese diplomacy in which Africa is portrayed as a hero thanks to which the People’s Republic of China was able to replace the Republic of China (Taiwan) on the UN Security Council. In fact, as the UN archives show, the support of African countries came late and was only expressed when Taiwan’s ouster became inevitable.

China has been heading four UN agencies simultaneously: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) [2019-2023], the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) [2015-2021], the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) [2013-2021] and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) [2015-2022]. It is also the only country that has never held so many directorates simultaneously, which is all the more important as these four agencies are highly symbolic. The FAO and UNIDO directorates underline China’s involvement in development, industrialization, and aid to poor countries. The ICAO and ITU supervision also show China as a technically innovative country in sensitive areas, having successfully transformed itself from a backward to a technologically advanced country. If China’s presence at the head of the ITU makes sense in the race, no longer for 5G, but for 6G, which Huawei intends to be able to market as early as 2030, its presence at the head of the ICAO was even more significant with the launch of an air silk route, after the setbacks of the Boeing 737 Max and on the eve of the certification of the Comac C919. The Silk Air Route is a project initiated by the conglomerate AVIC (Aviation Industry Corporation of China) to promote the export of Chinese aeronautical equipment, infrastructure, and services to countries along the New Silk Roads. It is an industrial project that strongly needs the support of the Chinese state to obtain the various certificates that establish the airworthiness of the exported material and equipment and, to this end, is included in the 14th Five Year Plan. Among the exportable equipment is the Comac C919, which is intended for the same markets as the Airbus A320 and the Boeing 737 Max. In other words, by economically and financially supporting African countries, China is building up a clientele of dependent countries that enable it to build its image and exercise definite political power: the instrumentalization of Africa contributes directly to the rebirth of the powerful China that Chinese leaders are so keen to see. Inadvertently cynical (or so one assumes), Yao Guimei(director of the Center for South African Studies at the China-Africa Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) sums up the relationship with Africa as “resources, markets, and votes.”

This instrumental cynicism was stigmatized at a colloquium held on 27 May 2022 under the auspices of the Culture magazine and the Eurasian Society for System Science Research Association. To epitomize the panelists’ views, I would say they insisted that China is economically invaluable to Africa, while Africa’s economic significance to China is extremely modest. However, Africa is politically relevant to China. They agreed that Chinese economic cooperation in Africa is the “ballast stone” – in other words, what stabilizes Sino-African relations – and that Africa should no longer be instrumentalized for political purposes, but should become the fulcrum of a new Chinese international economic strategy to better counter the international order endorsed by “the West led by the United States.” However, this questioning is likely to be implemented only to a very limited extent, as the White Paper “China and Africa in the New Era” (December 2021) and the 15th Five Year Plan (2021-2025) assign a specific place for Africa in the international division of labor as conditioned by China’s want to establish industrial chains that respect the “China First” principle. In the context of such an unequal international division of labor, this principle only reinforces African countries’ role as suppliers of raw materials, or as “resource countries” as they are typified in the 15th Five Year Plan.