This past June, the leaders of the world’s largest IMF economies and wealthiest liberal democracies gathered at Elmau castle in Germany’s picturesque Bavarian Alps for the annual G7 summit. Besides discussing obvious topics such as the Ukrainian war and global economic recovery, the gathering was an opportunity to unveil a major infrastructure development program—the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII).

Spearheaded by US president Joe Biden, PGII is in part a rebranding of his “Build Back Better” (B3W) domestic bill. The economic recovery plan was aimed at strengthening the US economy but had fallen flat in both Congress and before the public eye. PGII is rooted in B3W’s four pillars: healthcare, gender equality and equity, climate and environment, and digital connectivity. But it will include hard infrastructure projects, initially missing from the B3W investment portfolio, to reflect a clearer commitment to physical development all across the global south—with a special focus on Africa.

When the West uses liberal democracy as a yardstick for development, they fail to realize that it’s not ‘one-size fits all.

Money will be pulled from both government funding and the private sector (e.g. pension and insurance funds)—an act that will require coordination across multiple federal departments and agencies, says John Calabrese, the director of American University’s Middle East and Asia Project.

According to a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), this refreshed approach of using limited official finance to stimulate higher volumes of private capital will counteract China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI’s) high debt levels, where financing largely depends on opaque state-to-state channels.

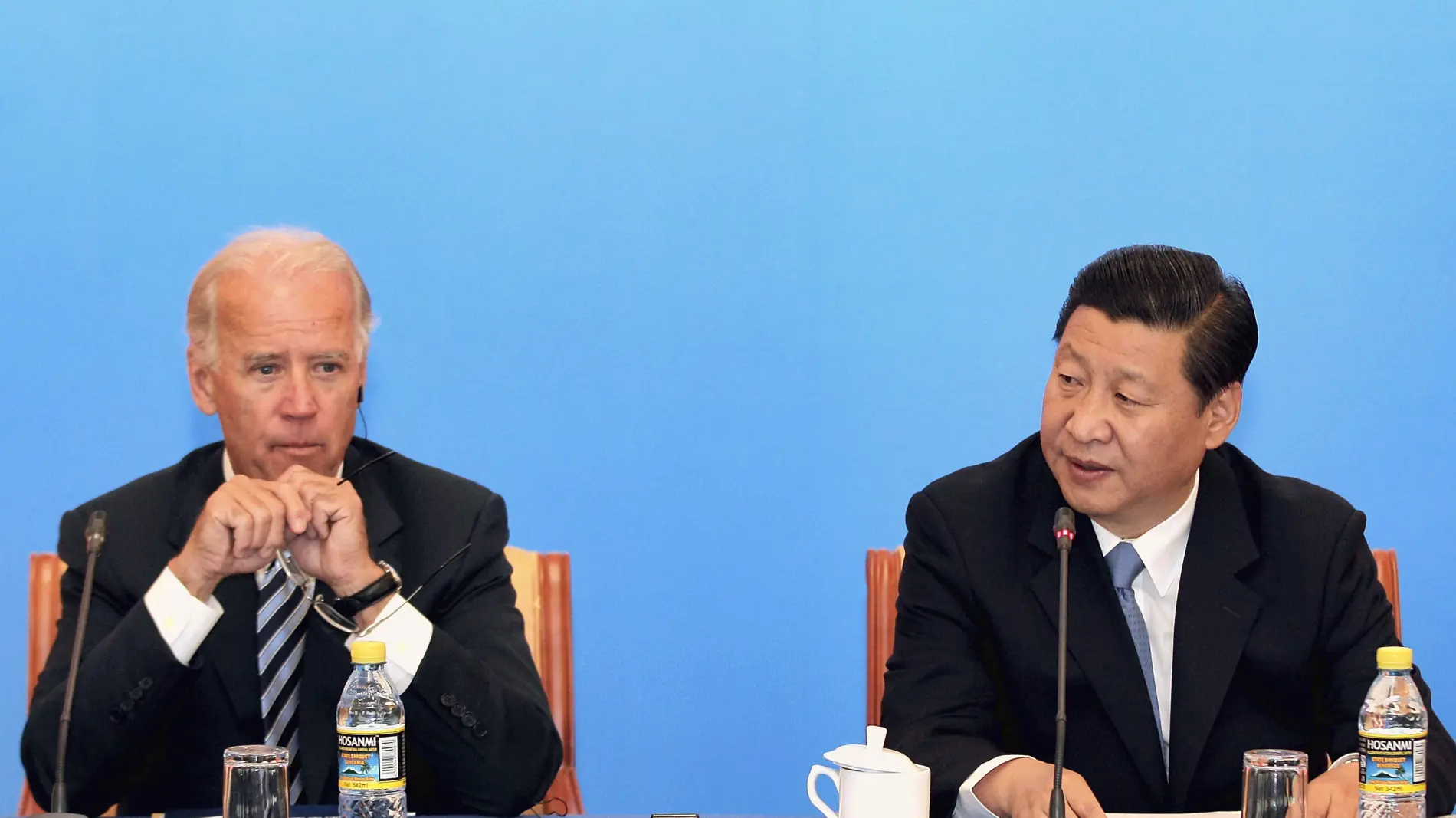

Build Back Better versus China’s Belt and Road initiative

According to a White House briefing, upcoming projects include a $2 billion solar project in Angola, $600 million to cover six submarine telecommunications cables connecting Singapore to France through Egypt and the Horn of Africa, and $25 million in the Uhuru Growth Fund I-A to grow small and medium-sized businesses in west Africa.

Calabrese says that this collective effort aligns with the Obama-Biden perspective that addressing global challenges requires a concerted strategy across like-minded states, particularly given the environment of major power grappling. Yet PGII has an undeniable reactionary air of countering China.

China has nearly a decade’s head start in the arena of African infrastructural development. President Xi Jinping’s well-publicized BRI has been making headway since 2013. BRI has been punctuated by countless speculations regarding a new form of neocolonialism and projecting western fears of China’s rising clout. The irony and racial tinges underlying these discussions, many by nations who were actual formal colonizers across Africa, oftentimes seemed lost.

Efem Ubi, an associate professor and director of research at the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs based in Lagos, says that he would welcome this step towards development if it’s genuine—yet he has serious concerns about PGII’s yet-unknown conditionalities and the lack of African inclusivity.

“When the West uses liberal democracy as a yardstick for development, they fail to realize that it’s not ‘one-size fits all.’ They then develop a system alien to many African socio-political dynamics, which actually can create endemic problems that stall progress.”

Africans are skeptical about the West’s motivation in Africa

Ubi points to a series of coups in Mali and Sudan over recent years as examples. “Democracy must be adapted to individual social structures. Yet no African state has adopted it smoothly so far.”

He explains how after the collapse of the former Soviet Union, many African countries took up democracy to access loans—which veered more toward pseudo democracy in practice.

“Governance should benefit citizens, not dictatorship or authoritarian rule. It should provide for citizens and allow for economic growth and development—meaning, let it precipitate into the positive changes in the human development index.”

The researcher adds: “It’s time that the West tries to respect each country’s position, tradition, and culture. Some of their conditions need to be toned down.”

“There should be a give and take, concessions, not just a goal to outdo China,” Ubi tells Quartz. “Besides, B3W was a failure—so is this rebranding really going to make a difference? Why is it a group of countries coming together to aid the developing world? China did it solo.”

Elijah Munyi, an assistant professor of International Relations at the United States International University based in Nairobi, believes that the motivations of both the western world and China are largely the same—“to exert power and influence.” “Whether the US or Europe is late in the game, is immaterial,” he tells Quartz. “What is fascinating for me is the one sided-ness of these decisions.”

Build Back Better not only lacks originality, but also creativity

Although the infrastructure needs of low and middle-income countries are enormous, Calabrese believes PGII is lacking somewhat in both creativity and selectivity. “The US cannot possibly ‘compete’ with China in every country and every sector,” the researcher says, particularly in light of the massive funds at the disposal and direction of the state authorities.

“I think the initiative will only gain traction if the US and its G7 partners can drill down into each of the PGII’s four pillars, develop criteria for targeting or at least coordinating the targeting of just a few countries…to determine which projects would best meet their needs and be viable—irrespective of Chinese activities in those countries.”

Regarding the proposed submarine telecommunications cable, Calabrese points out that it’s undoubtedly meant to provide an alternative to China’s 7,500-mile undersea Peace Cable. “I do not necessarily see a ‘second cable’ as superfluous,” the researcher says. “The US has been most concerned about potential Chinese ‘control’ over the flow of information. This project, if it materializes, would presumably provide ‘users’ with a ‘safe’ option.”

Justin Siocha, a communications practitioner based in Nairobi who specializes in Chinese economic aid in Africa, says that African countries will take money and aid from anyone. “This is good news for them, especially now with all the economic crisis after covid.” But the power struggle is apparent even in this supposed act of altruism. “The West—the U.S. in particular—is trying to hold on to their ‘super powers.’ A main challenge in this sense, economically speaking, is China.”

But given China’s established history in Africa, the West will need to play catch up, Siocha continues. He agrees with Ubi that the West will have to manage its expectations with regard to providing conditional aid. “If [the West] wants to contain China, they have to reduce those democratic ideals. In my opinion, it’s a good time for African countries to play ball and gain from the competing actors.”

Siocha is confident that changes will happen. “The reality is Russia has resources and China has money,” he says. “The West has neither at the moment. But they have been controlling the world for long.”