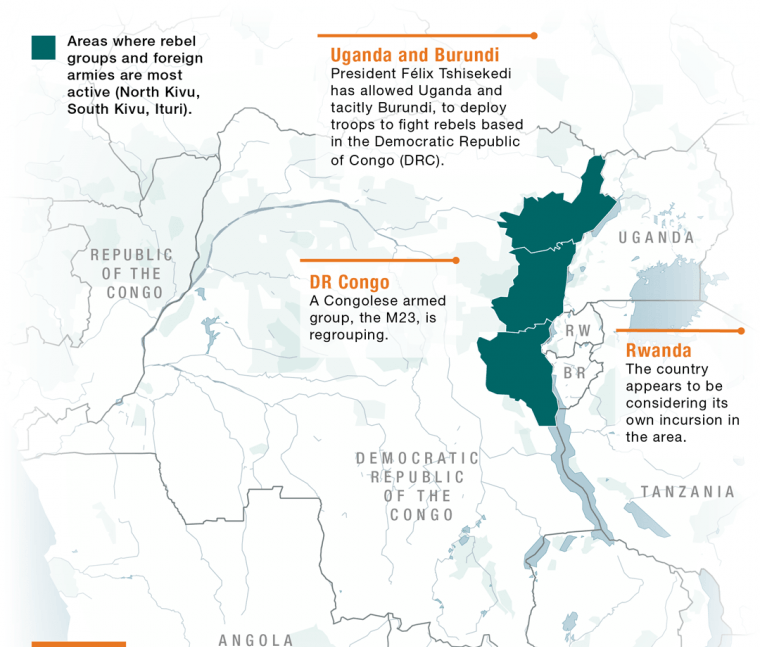

Fighting in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo is intensifying, with Ugandan and Burundian soldiers in pursuit of rebels and Congolese insurgents on the rebound. With help from its allies, Kinshasa should step up diplomacy lest the country become a regional battleground once more.

What’s new? President Félix Tshisekedi has allowed Uganda to deploy troops to fight rebels based in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and is tacitly permitting Burundi do to the same. Rwanda appears to be considering its own incursion in the area. Meanwhile, a Congolese armed group, the M23, is regrouping.

Why does it matter? Tshisekedi’s decision to invite in foreign troops could roil the already unstable east by triggering proxy warfare or energising Congolese rebels. For years, rivalries among the DRC’s neighbours have spawned myriad insurgencies that they could use against one another. Uganda’s military campaign has particularly irked Rwanda.

What should be done? Tshisekedi should set rules for foreign intervention on Congolese soil, while intensifying efforts to dissuade Rwanda from deploying forces across the border. Drawing on Kenya for support, he should organise fresh talks with neighbouring countries to rethink further military action and develop a comprehensive plan for negotiations with armed groups.

I. Overview

President Félix Tshisekedi may have opened Pandora’s box by inviting troops from neighbouring countries to fight rebels based in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In November 2021, following deadly bombings in Uganda’s capital Kampala, Tshisekedi allowed Ugandan units to cross into the DRC’s North Kivu province in pursuit of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan rebel coalition whose largest faction has sworn allegiance to the Islamic State. The following month, Burundian soldiers reportedly marched into the DRC to battle the RED-Tabara rebel group. These interventions are causing fresh upheaval in a country that has suffered greatly from regional rivalries. Rwandan President Paul Kagame has warned that he might dispatch soldiers as well, while Kenya-led talks have revived a proposal for an East African intervention force. Tshisekedi should set clear rules for foreign military operations in the DRC. Drawing on Kenya’s support, he should redouble efforts to convince Rwanda not to send in troops, pointing out the risks to Rwanda’s reputation should it do so and addressing some of Kagame’s concerns.

Volatile for years, relations among the Great Lakes neighbours had begun to improve in recent months. In January, Kagame and Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s president, were inching toward rapprochement after a three-year stalemate. The region’s two heavyweights had fallen out amid a slew of mutual recriminations, with each accusing the other of backing rebels operating from the eastern DRC. Burundi and Rwanda were also on better terms after Evariste Ndayishimiye took over the Burundian presidency from Pierre Nkurunziza, who died suddenly in June 2020. But the activities of militias in the eastern DRC are putting these historically fraught ties under renewed strain, potentially widening rifts between Rwanda and Uganda, and even Rwanda and Burundi. The surprising re-emergence of the M23, a Congolese insurgency that had been dormant for almost a decade, is particular cause for concern, given its previous ties to both Kampala and Kigali.

” For years, the DRC’s neighbours have used militias in its east … as proxies. “

For years, the DRC’s neighbours have used militias in its east – Congolese and foreign alike – as proxies. Rwanda and Uganda especially have long sought to exert influence in the area, whose abundant mineral resources buttress their economies. Since assuming office in 2019, Tshisekedi has tried to tackle the dozens of Congolese and foreign groups by mending relations with his neighbours – through regional diplomacy, at first, and later through bilateral talks. He initially had some success, mainly by bringing Kagame and Museveni together under a quadripartite framework with his Angolan counterpart, João Lourenço. Those efforts have since petered out. The DRC’s admission to the East African Community in March gave a boost to regional diplomacy, with Kenya organising talks in Nairobi. But allowing foreign military involvement on Congolese territory could undercut prospects of such diplomacy and could even generate wider confrontation. The presence of Rwandan troops in the DRC could reignite rivalries over turf and invigorate local insurgents, undermining Tshisekedi’s stated goal of stabilising the area.

Several steps could reduce escalation risks in the east. The Congolese president could set rules for any foreign intervention, clarifying the objectives, duration and potentially the area of operation of those he has greenlighted, particularly that of Uganda. He could endeavour to persuade Kagame not to send troops into the DRC. Transparency about Uganda’s operation might help mollify Kagame, but to bolster his case, Tshisekedi can also lay out the reputational costs of a Rwandan intervention for Kigali. The Congolese president, who has just assumed the helm of the Regional Oversight Mechanism of a 2013 peace agreement, the Peace, Security and Cooperation Framework (PSCF), could use his tenure to reinvigorate his regional diplomacy. Kenya should push Tshisekedi to develop a comprehensive plan for negotiations with armed groups. Finally, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, a body comprising states in the region and a PSCF guarantor, should continue collecting evidence of foreign support for rebels in the DRC.

II. Kagame’s War Rhetoric

On 8 February, President Kagame gave a thundering 50-minute speech to the Rwandan parliament, decrying a threat to the country’s security emanating from the DRC’s Kivu provinces. He cited alleged connections between the ADF and one of his longstanding foes, the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR), a remnant of the Rwandan Hutu militia responsible for the 1994 genocide. In his native Kinyarwanda, interspersed with English, Kagame said the danger was great enough that he was considering deploying troops in the eastern DRC without Tshisekedi’s approval. “As we are a very small country, our current doctrine is to go and fight the fire at its origin … We will wage war where it started, where there is enough space to wage war”, Kagame said. “We do what we must do, with or without the consent of others”.

Kagame’s speech came after the Ugandan and Burundian armed forces launched their own military operations in the DRC. In November 2021, Tshisekedi authorised Uganda to deploy soldiers in the eastern DRC to fight the ADF, which Museveni holds responsible for the lethal bombings in Kampala.

In late December, presumably with Tshisekedi’s blessing, Burundian troops crossed into the DRC to target the RED-Tabara insurgency, a Tutsi-led group opposing the Hutu-dominated government in Bujumbura. Those rebels had fired mortar shells at Burundi’s international airport in September and killed about a dozen soldiers and police in an attack on a Burundi-DRC border post three months later.

Ugandan and Rwandan officials are in the eastern DRC often to gather intelligence, but they tend to move under the radar. (Rwanda consistently denies any such activity.)

Uganda’s deployment is the most substantial open foreign intervention in the DRC since the devastating Congolese wars ended in 2003.

Along with Burundi’s clandestine deployment, Rwanda’s threat to get involved and the possible formation of an East African force, Uganda’s deployment has sparked fears of broader outside military involvement and cast further doubt upon Tshisekedi’s ability to stabilise the east.

” [President] Tshisekedi has tried several ways of tackling the dozens of armed groups plaguing the eastern DRC. “

Tshisekedi has tried several ways of tackling the dozens of armed groups plaguing the eastern DRC. At his presidency’s outset, he favoured a regional approach. In 2019, he floated a plan to invite Burundi, Rwanda and Uganda to carry out joint military operations in the east under the Congolese army’s authority. This plan went nowhere, however, allegedly because each of Kampala and Kigali were wary of seeing the other expand a sphere of influence in the DRC.

Unable to ease the deep-rooted mistrust between the two, Tshisekedi changed tack and began to pursue bilateral cooperation. In March 2021, Congolese and Rwandan officials drew up an operational plan for joint military action in the east, though official follow-up has thus far been limited. In July, the DRC and Burundi agreed to cooperate militarily as well, following a face-to-face meeting between Tshisekedi and Ndayishimiye that was likely a prelude to the deployment of Burundian troops in South Kivu province. Four months later, and after months of talks between Tshisekedi and Museveni, Ugandan troops marched into the DRC.

Uganda’s military venture is public knowledge, though contradictory statements have reinforced the impression that the parties have no clear agreement about its scope. Though Tshisekedi authorised the operation, the DRC’s government spokesman denied the Ugandan troops’ presence at first.

Since then, Congolese and Ugandan authorities have presented the operation as a joint military exercise. In reality, Uganda appears to be firmly in charge: its military has claimed several battlefield gains, from capturing ADF camps and freeing hostages to killing dozens of ADF fighters. Yet reports of direct clashes between ADF rebels and Ugandan troops are sparse. The UN peacekeeping mission in the DRC, MONUSCO, whose Force Intervention Brigade (FIB) is also targeting the ADF, also appeared slightly surprised by the Ugandan troop deployment, as President Tshisekedi informed the mission only days prior to the start of its operations.

There are also questions about the Ugandan deployment’s duration. Tshisekedi said in December it would be brief; in contrast, Uganda initially signalled that it would depart only after its soldiers had subdued the ADF. In January, the Ugandan units extended their area of operations from North Kivu to north-eastern Ituri province, where many ADF rebels had fled during the campaign’s first phase. The same month, Uganda’s defence forces submitted a budget to parliament requesting additional funding, indicating that troops are likely to stay in the DRC until at least June 2023. In April, Museveni said he had deployed as many as 4,000 troops. Then, in a surprise tweet on 17 May, Museveni’s son and commander of the land forces, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, announced the end of the Ugandan operation and the withdrawal of troops within two weeks. His tweet appeared to provide clarity on the deployment’s initial duration: it has apparently been scheduled for six months. But just hours later, the general seemed to backtrack, saying Museveni and Tshisekedi could still decide to extend the mission by six months.

” Burundi’s incursion into South Kivu is shrouded in secrecy. “

Burundi’s incursion into South Kivu is shrouded in secrecy. In late December, residents of the province’s Uvira territory reported seeing about 400 Burundian soldiers and Imbonerakure, Burundi’s notorious ruling-party youth militia, cross the Rusizi river between the two countries.

They then reportedly entered an alliance with the Gumino and Twigwaneho ethnic groups and several other smaller Mai-Mai groups against RED-Tabara, which has formed ties with another Burundian insurgency, Forces nationales de libération (FNL), and Congolese Mai-Mai militias. The Burundian army reportedly sustained heavy losses, while thousands of residents fled the violence. Burundi has repeatedly denied that its troops are fighting in the DRC, however.

The Congolese government has remained silent on the issue.

The likelihood that Rwanda will enter the fray is real. Kagame’s February speech indicates that he is deeply unhappy with his neighbours’ military operations in the DRC, though he seems well aware of the obstacles he would face if he were to order Rwandan troops to follow suit.

Many Congolese have vivid memories of Rwanda’s brutal tactics during its previous military campaigns in the DRC. Moreover, Rwanda’s historical support for a range of insurgencies in the eastern DRC feeds widespread suspicion among Congolese about its intentions. By mid-December, two weeks after Uganda launched its offensive against the ADF, the Congolese and Rwandan police forces agreed to enhance cross-border cooperation. Rumours that a Rwandan crime-fighting force may deploy in Goma, Congo’s sprawling commercial hub near the Rwandan border, have already sparked deadly protests in the city.

Whichever way Kagame decides to proceed, tensions between him and Tshisekedi have clearly racked up a notch since Ugandan and Burundian troops entered the DRC. Despite Tshisekedi’s efforts to bring Kagame onto his side, acrimony between the two leaders runs deep. Rwandan officials claim that Tshisekedi has not allowed them to “take care of the FDLR” – a longstanding complaint of Kagame’s that he also levelled at Tshisekedi’s predecessor, Joseph Kabila – even suggesting that the Congolese army cooperates with the group. For his part, Tshisekedi worries about Rwanda’s regional ambitions. “It is unrealistic and unproductive, even suicidal, for a country in our sub-region to think that it can always benefit from maintaining conflicts or tensions with its neighbours”, he told diplomats in late February.

III. Rwanda-Uganda Rivalry and the Return of the M23

Intense antagonism between Kagame and Museveni has often fanned the flames of conflict in the Great Lakes region. Uganda’s incursion into the DRC has stoked fears that Rwanda may get involved too, whether to compete for control of territory or to seek vengeance for previous wrongs. Traditionally tempestuous relations between the former allies have taken a turn for the worse over recent years.

Months of increasingly hostile mutual allegations culminated in Rwanda’s abrupt closure of the bustling Gatuna border crossing in February 2019.

Among other things, Kagame accused Kampala of harassing Rwandans in Uganda. Commerce between the two countries all but collapsed as the border shut. The measure disrupted trade throughout East Africa, as Gatuna sits on the principal route for trucks carrying supplies from Kenya’s Mombasa port into the interior, with over 2,000 trucks crossing each month. The COVID-19 pandemic then compounded the closure’s harmful effects.

Mediation by Tshisekedi and Lourenço brought Rwanda and Uganda together to sign a memorandum of understanding in August 2019 but yielded no further concrete action. Relations finally improved after General Muhoozi paid a visit to Kagame in January 2022.

He flew back to Uganda with a Ugandan soldier Rwanda had arrested in November. In return, Museveni made an important conciliatory gesture by replacing his military intelligence chief, General Abel Kandiho, whom Kagame allegedly wanted removed, because he holds him responsible for abuses against hundreds of Rwandans in Uganda. Rwanda then said it would reopen the border. A further sign of warming ties was Kagame attending Muhoozi’s birthday party in April. During his first visit to Kampala in four years, he also met with Museveni, reportedly to discuss regional dynamics.

” Economic rivalries are part of the reason for the enmity between Rwanda and Uganda. “

Economic rivalries are part of the reason for the enmity between Rwanda and Uganda. The two have long vied for control of the eastern DRC’s natural resources. As much as 90 per cent of Congo’s gold is smuggled to neighbouring countries, with the bulk arriving in Rwanda and Uganda.

Both countries list gold among their biggest foreign exchange earners, though neither produces much itself. Besides significant deposits of gold and other minerals, the eastern DRC also has oil, notably under Lake Albert, which spans the Uganda-DRC border. In February, French company TotalEnergies approved a $10 billion oil project on Uganda’s side of the lake that will turn the country into a significant energy producer. Aside from technical difficulties, squabbling over the route of a pipeline to an East African port had delayed the project for years.

(The company also has a memorandum of understanding with Rwanda to help develop its energy sector.)

With both Uganda and Rwanda relying on access to the eastern DRC to bolster their economies, Tshisekedi faces a difficult balancing act. A June 2021 agreement between Tshisekedi and Kagame giving a Rwandan company rights to refine gold produced in Congo reportedly irritated Kampala; that Tshisekedi went along with the deal also surprised many Congolese.

For his part, Kagame is said to be upset about a massive Ugandan road project in the eastern DRC that aims to open trade routes to three eastern Congolese cities and thus provide alternatives to the Gatuna/Katuna crossing. At least one of these roads is allegedly too close to Rwanda’s border – and thus in what Kagame perceives as Kigali’s sphere of influence – for his liking.

There are reasons to believe that Museveni is as interested in safeguarding Uganda’s economic projects in or near the eastern DRC as he is in subduing the ADF. Ugandan authorities linked the military incursion directly to the Kampala bombings.

But Museveni had allegedly obtained Tshisekedi’s approval to deploy troops in August, prior to the attacks, and Uganda undertook its road project and its anti-ADF campaign almost simultaneously, indicating months of advance planning – though admittedly the ADF was a concern in Kampala before the group’s strikes. Military experts working on the region told Crisis Group that Uganda does not envisage defeating the ADF militarily or staying for a limited period of time. The fact that the Ugandan army used only one border crossing to enter the DRC appears to substantiate this theory, as ADF fighters were thus able to scatter to the north west. Ugandan troops could have cornered the group had they entered the DRC from two or more directions.

Whatever Uganda’s reasons, its offensive has angered Rwanda, as Kagame’s speech indicated. He suggested that he might consider sending Rwandan contingents across the Congolese border without a prior bilateral agreement.

The same day, seemingly in response to Kagame’s belligerent remarks, Museveni appointed Kandiho as head of the Ugandan police, reversing his previous decision to appease Kagame by sidelining the former intelligence chief.

It appears that the two presidents have scores yet to settle.

” [Uganda and Rwanda] continue to trade accusations, notably citing each other’s involvement with the [Allied Democratic Forces]. “

The two countries continue to trade accusations, notably citing each other’s involvement with the ADF. Rwandan officials say Uganda supports the group or at least does not do enough to fight it; Ugandan officials lob the same charge at Rwanda.

In November, a Rwandan dissident alleged that Rwanda sponsors the ADF, implicating two senior army officers. That dissident was a former member of the Rwandan National Congress (RNC), a group led by Tutsi defectors from Kagame’s government, with a military wing in the eastern DRC. Rwanda has repeatedly criticised Uganda for allowing the RNC on its territory, for instance pointing to a Ugandan work permit issued in January to SelfWorth Initiative, a human rights outfit Rwanda sees as a RNC front. In February, Museveni’s son alluded to RNC activities in Uganda in what seemed to be an acknowledgement of the group’s capacity to hurt Uganda-Rwanda relations. It was unclear if he was commenting on the government’s behalf, but in April Uganda reportedly deported an influential RNC member, seemingly in an attempt to assuage Rwanda’s concerns.

An even more pressing concern is the sudden re-emergence of the M23. In 2012, with backing from Rwanda and Uganda, this group led the last big rebellion on Congolese soil, briefly capturing Goma before UN and Congolese troops defeated it the following year. Most combatants fled to Uganda, while the remainder sought refuge in Rwanda. A December 2013 peace agreement emphasised that M23 fighters should return to the DRC, without saying who was responsible for their repatriation. Some former rebels eventually trickled back on their own accord. In 2017, rebel commander Sultani Makenga tried to revive the movement by leading an estimated 200 ex-fighters back into the DRC before settling in the Mikeno sector of Virunga National Park, which borders Rwanda and Uganda. The group then largely fell out of view, though some members reportedly worked as hit men “settling” disputes in the Rutshuru area.

Renewed attacks by the M23 could deepen the rift between Uganda and Rwanda. The group resurfaced on 7 November with a raid on Congolese army positions in Rutshuru territory, bordering Rwanda and Uganda.

Congo’s military immediately blamed the M23, with some in Tshisekedi’s entourage claiming that the attackers arrived from Rwanda. The president of Uganda’s M23 wing denied involvement, but did acknowledge the presence of Makenga and his men on Congolese soil. Rwanda also denied that it was involved, blaming the Uganda cohort for the attack. (Uganda’s deputy foreign minister dismissed Rwanda’s accusation as “rubbish”. ) Analysts told Crisis Group that Makenga likely overreacted to a security incident. In a larger attack on 24 January in Nyesisi, near the Virunga National Park, alleged M23 rebels killed about 40 Congolese soldiers, including a colonel. Some analysts believe that Rwanda backed this assault, as it occurred near Uganda’s road works. Kagame immediately denied that Rwanda was involved.

How much the M23 can further destabilise the east is unclear, but the group could create headaches for everyone in the Great Lakes region. On 28 March, its fighters clashed with the Congolese army and attacked communities near Rutshuru. Fighting also raged near the border, forcing some 6,000 civilians into Uganda.

Kampala dispatched extra troops to the eastern DRC to protect the road project’s machinery. North Kivu’s military governor accused Rwanda of supporting the M23, parading two captured men he said were Rwandan soldiers before journalists. Rwanda refuted the accusations. The next day, a UN helicopter with eight peacekeepers crashed in the area, killing everyone on board. The Congolese army said the M23 had downed the aircraft. On 1 April, the M23 unexpectedly announced a unilateral ceasefire, encouraging Congolese authorities to initiate negotiations. The Congolese army rejected the offer, launching a counter-offensive on 6 April. It quickly lost strategic positions to the M23, however.

The parties’ forward positions are near each other at present, leading to sporadic clashes.

Part of the reason that the M23 has returned with such force is that Tshisekedi’s government has struggled since coming into office in 2019 to act decisively on the 2013 peace agreement. According to the deal, DRC authorities were to demobilise and disarm M23 fighters and give amnesties to most of the rank-and-file. But the agreement had no solution for how to deal with perpetrators of severe human rights violations, including the commander, Makenga, who were excluded from repatriation. Tshisekedi previously said he would lift arrest warrants for some rebels accused of atrocities, but to date he has not done so, possibly due to anxiety about how people would view such a move. The M23 enjoys little popular support and many Congolese would baulk at offers of return or amnesty to its fighters.

Meanwhile, M23 delegates, reportedly including a representative of Makenga, have been struggling to get an audience with Tshisekedi. Some Congolese opposition figures worry that the government could use a spiralling rebellion to suspend the 2023 presidential election in the east, as voters there largely favour the opposition.

IV. Burundi and Rwanda Rekindle Ties

If Rwanda’s relations with the DRC and Uganda are evolving, its ties to Burundi have significantly improved.

While Burundi and Rwanda got along reasonably well in the past, their relationship deteriorated in the 2010s amid mutual allegations of meddling in domestic affairs. Animosity peaked during Burundi’s 2015 political crisis, when protesters came out en masse against President Nkurunziza’s push to secure a third term through changes to the constitution. The crisis escalated when a coup attempt unleashed a brutal crackdown by security forces, which in turn sent tens of thousands fleeing to neighbouring countries. Nkurunziza believed that Rwanda had orchestrated the coup attempt. Much to his dismay, and seemingly confirming his suspicions, Rwanda awarded several coup plotters refugee status and gave uprooted Burundian journalists permission to broadcast from Kigali.

Throughout his third term, Nkurunziza accordingly shunned Rwanda, as he did most Western countries that had criticised the security forces’ abuses and the subsequent flawed elections.

Nkurunziza and Kagame also accused each other of supporting rebel groups. For instance, Nkurunziza openly stated that Rwanda was backing RED-Tabara, providing material and logistical support.

For its part, Rwanda was furious that Burundi appeared to be turning a blind eye to FDLR activities in the country’s north west and charged Burundi with working alongside Uganda to forge an alliance between the FDLR and the RNC. Kigali also said Burundian intelligence agents and members of the ruling party’s youth militia were “embedded” with armed groups in South Kivu.

The two countries swiftly repaired ties after power changed hands in Burundi. Nkurunziza’s successor, Ndayishimiye, almost immediately tried to end Burundi’s isolation. The timing for Rwanda, whose economy was beginning to buckle under the strain of the border closure with Uganda, was propitious. High-ranking officials on both sides are now on speaking terms again and rumours abound of a meeting between the two presidents.

In March 2021, Kigali barred three Burundian radio stations from broadcasting from Rwanda. The government has also started to facilitate the return of Burundian refugees. But the two countries’ leaders are unlikely to meet before Rwanda hands over the coup plotters, which it has so far refused to do. For Burundian officials, the request is a prerequisite for full restoration of relations. Kigali’s refusal likely also drives Burundi’s decision to keep its border with Rwanda closed, despite Rwanda reopening all land frontiers, including with Burundi, in March 2022.

” [Burundi and Rwanda] are now cooperating against armed groups. “

Still, the two countries are now cooperating against armed groups. Burundi appears to have reversed its policy of sheltering the FDLR, attacking the group’s forest hideout in February 2021. When Burundian troops clashed with Rwandan soldiers who reportedly pursued members of the FDLR and the FNL, another anti-Kagame rebel group in the same area, a call between the two countries’ military intelligence chiefs prevented an escalation.

An exchange of captured insurgents has further eased tensions. In July, Rwanda extradited nineteen RED-Tabara combatants it had arrested the year before to Burundi. In return, Burundi delivered eleven alleged FNL rebels to Rwanda.

The intergovernmental body, International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, supervised the handover at the border.

RED-Tabara remains a bone of contention, however.

Following the aforementioned attack on Bujumbura airport in September 2021, Burundi issued international arrest warrants for opposition politician Alexis Sinduhije, whom authorities believe leads RED-Tabara, as well as officials of his political party living in exile. Burundi’s prosecutor asked countries harbouring these fugitives to extradite them, warning that failure to comply with his request would compromise regional peace and security. While Sinduhije resides in Belgium, several senior RED-Tabara rebels live in Kigali. It is unclear to what extent Rwanda is helping RED-Tabara at present. Some analysts believe that its backing for the group has diminished, giving Burundi the confidence to fight the rebels, while others think it still provides some support.

V. The Need for Regional Diplomacy

Tshisekedi has repeatedly stated his determination to stabilise the DRC’s restive east. At first, he rightly put a premium on regional diplomacy, hosting quadripartite meetings bringing Kagame, Museveni and himself together with Lourenço. The process stalled amid the COVID-19 pandemic, yielding little progress apart from a virtual meeting in October 2020. With Lourenço preoccupied with domestic politics, and Tshisekedi’s former chief of staff and coalition partner Vital Kamerhe, who apparently had been running Great Lakes policy on the DRC’s side, convicted for corruption, Tshisekedi’s enthusiasm for that regional track waned.

The Congolese president then changed tack and sought to subdue armed groups by force. In May 2021, he imposed a state of siege in Ituri and North Kivu, placing the two provinces under military control. His decision to invite Ugandan and Burundian troops into the DRC, alongside Congolese army operations, further illustrates his emphasis on a military approach. But military action has time and again failed to pacify the east, as the DRC’s history of cyclic warfare shows. In April 2022, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta convened Museveni, Ndayishimiye, Tshisekedi and Rwanda’s foreign minister for talks in which they agreed to form a regional force to fight rebels in the eastern DRC, partly to double down on the military approach, but partly to facilitate peace talks with Congolese armed groups.

Building on this meeting, President Tshisekedi can take a number of steps to reduce the risk of a free-for-all in the eastern DRC.

” [President Tshisekedi] should urgently set clear rules for foreign militaries operating in the eastern DRC. “

First, he should urgently set clear rules for foreign militaries operating in the eastern DRC – both for the sake of its inhabitants, who are at risk of getting caught in the crossfire, and also to help assuage Kagame’s concerns. He should be more transparent about what he agreed upon with his neighbours: the duration – in particular after Muhoozi’s May tweets – and geographic scope of their military involvement, their objectives and, crucially, their forces’ behaviour. Without such agreement among partners, the neighbours’ involvement could escalate into a regional conflagration, stir up greater local resentment and spoil the fruits of Tshisekedi’s efforts to reconcile with his neighbours. Uganda and Burundi should themselves provide more clarity about their activities. The secrecy surrounding Burundi’s incursion has riled even its own troops. In February, Burundi’s military intelligence allegedly ordered the execution of about twenty Burundian soldiers in Uvira for insubordination. The men had reportedly asked for official recognition of their mission and a clear order of battle in line with military regulations.

Simultaneously, Tshisekedi should redouble efforts to dissuade Rwanda from sending soldiers to the eastern DRC.

On 24 February, Tshisekedi took over from Museveni as rotating chair of the PSCF’s Regional Oversight Mechanism. As chair, he can urge his regional counterparts to comply with the agreement’s stipulations that signatories refrain from interfering in one another’s domestic politics and assisting armed groups. In particular, he should convince Rwanda to remain a party to the agreement; that Kagame did not attend the chairmanship handover summit in Kinshasa suggests he may be turning his back on the alliance. In meetings with Kagame, Tshisekedi should stress that intervening in the DRC could damage Rwanda’s standing in the region – which has risen of late due to Rwandan troops’ successes in Mozambique and the Central African Republic (at the invitation of those countries’ governments). A military operation in the DRC might also undercut Rwanda’s business interests at a time when it is building four ports on Lake Kivu to facilitate trade.

Kagame is renowned for his reluctance to compromise in matters related to the eastern DRC, but in trying to persuade him, Tshisekedi may have a useful ally in Kenya, which has no interest in escalation in the region. In March, the DRC joined the East African Community and its large population makes up an important market for Kenyan products. Additionally, since 2021, Kenya contributes troops to the UN peacekeeping mission’s FIB, which is based in the eastern DRC, and has a mandate to take on armed groups. The FIB was instrumental in defeating the M23 in 2013 and reportedly will fight that group again too.

Following the April meeting in Nairobi at which Rwanda was represented by its prime minister, Kenyatta should work to ensure Kagame’s attendance at a second regional meeting. He should also use the influence he enjoys to press upon Kagame the costs of deploying forces unilaterally in the DRC.

The Nairobi meeting unexpectedly put greater emphasis on negotiations with Congolese rather than foreign armed groups. The participants threatened to deploy a regional force to stabilise the eastern DRC unless Congolese armed groups agree to negotiations with Kinshasa. They hastily cobbled together a first round of talks with the leaders of eighteen armed groups, but the precise goal and scope of this dialogue are still murky. Selection criteria for attendees were unclear and some of the most violent groups, such as the Cooperative for the Development of the Congo, active in Ituri, and Mai-Mai Yakutumba from South Kivu, were not there. Nor did the talks include foreign armed groups, such as the ADF, RED-Tabara and the FDLR, while the Congolese authorities kept the M23 branch loyal to Makenga out of the discussions.

Preparations for a second meeting in Goma are under way.

Kenya should push Tshisekedi to develop a comprehensive plan, with assistance from the UN, which could help shape the contours of the effort. True, talks with armed groups in the DRC’s east would face huge challenges. Many groups are unlikely to demobilise without jobs for their fighters – which would require better reintegration plans than in the past – and security guarantees, which are hard unless the Congolese security forces establish a greater but less predatory presence in the region, itself no small hurdle. Whether talks would incorporate foreign forces is unclear. While Burundi says it may be open to talks with RED-Tabara and the FNL, little suggests a similar process is on the cards with Rwandan rebels, let alone the ADF, and how much talks with Congolese groups would address Rwandan and Ugandan involvement is unclear.

Still, given support from at least some countries in the region for such an approach, it is worth Tshisekedi fleshing out what a more thoroughgoing strategy – laying out what would be on offer for groups demobilising and what would happen to those refusing to do so – would entail.

” The [East African] force option … is likely to encounter great technical, logistical and financial difficulties. “

Both Tshisekedi and Kenyatta should also be wary of investing too much capital in exploring the idea of an East African force that regional leaders envisioned in Nairobi. Assembling such a force under a unified command and control would be a better option than each neighbour deploying its own forces separately, which could lead to them competing with one another. But the regional force option, which was already floated some years ago, is likely to encounter great technical, logistical and financial difficulties. Its feasibility is far from clear. Furthermore, most countries that would contribute troops already have soldiers on Congolese soil and it is uncertain how a joint force of East African states, including Kenya and Uganda, would sit alongside Uganda’s operation in North Kivu and Kenya’s contribution to the FIB, let alone the Burundian troop deployment to South Kivu.

In any case, more boots on the ground in the eastern DRC, even under a unified command, may well do more to engender instability than to curb violence.

Lastly, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region, which is a PSCF’s guarantor, should keep collecting evidence of foreign support for armed groups in the DRC. The Expanded Joint Verification Mechanism is mandated by the PSCF to probe allegations filed by regional states. For instance, it could look into recent M23 attacks to ascertain if a neighbouring state was indeed complicit. Though a difficult undertaking, independent verification of regional governments’ support for rebels could then provide a basis for dialogue that Tshisekedi would supervise as chairman of the PSCF’s Regional Oversight Mechanism. All regional leaders should realise that they have a shared responsibility to prevent a new war around the Great Lakes, as all stand to lose from another conflict.

VI. Conclusion

On the surface, Great Lakes countries are patching up their differences. Yet military operations by Burundi and Uganda in the eastern DRC, combined with continued rebel activity, could reignite historical antagonism between neighbours and further destabilise the DRC. Tshisekedi’s licence to Uganda to deploy troops and his tacit acquiescence in Burundian forces’ incursion to fight rebels on Congolese soil have annoyed Rwanda. Kagame, who in February alleged that insurgents threaten his country’s security, could decide to back Congolese rebels or send his own contingents across the border without prior approval. Tshisekedi should redouble efforts to balance the competing interests of his neighbours, clearly delineate what Uganda’s operations will do and convince Rwanda to commit to regional diplomacy rather than renewed warfare. Foreign military operations could generate further proxy conflicts in the region. Long torn apart by outside meddling, it can ill afford another war involving the DRC’s neighbours.