Principal Findings

What’s new? UN-led efforts to broker a ceasefire in Yemen have repeatedly stalled due to a standoff between Huthi rebels and the internationally recognised government over who has authority to control goods, particularly fuel, entering the Red Sea port of Hodeida. With the conflict escalating, the UN is struggling to make headway.

Why does it matter? The economy has become an integral part of the parties’ efforts to strengthen their own positions while weakening their rivals. The economic contest has fuelled the fighting at the front and impeded attempts at peacemaking. But diplomats working to stop the war have too often sidestepped the issue.

What should be done? Yemen needs an economic ceasefire as much as a military one. In concert with other UN actors, the new UN envoy should launch a mediation track to identify the economic conflict’s key players and begin to lay the groundwork for an economic truce even while the shooting continues.

Executive Summary

Yemen is caught up in overlapping emergencies that have defied mediation. In the north, bloody battles rage for control of Marib governorate between the internationally recognised government of Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi and the Huthi rebels who ousted him in 2015. Hadi’s government prevents fuel from entering the Huthi-held port of Hodeida, and a tug of war over the riyal, Yemen’s currency, has led to its collapse in nominally government-controlled cities. These crises form part of a struggle over the economy – call it an economic conflict – that has compounded Yemen’s humanitarian crisis, accelerated its political and territorial fragmentation, and stymied peacemaking. To date, mediation efforts have tended to treat economic matters as technical issues or sought to address them as “confidence-building measures” enacted in service of political dialogue. The new UN envoy should recognise them as core to the conflict and negotiate an economic ceasefire at the same time, and in much the same way, he seeks to arrive at a military truce.

The economic conflict pits the Hadi government against the Huthi rebels for control of the country’s natural resources, trade flows, businesses and markets. State and non-state institutions that facilitate and hinder trade, such as banks, customs authorities and other regulatory bodies, along with the parties’ respective security services, play supporting roles. The Huthis’ advantage in this struggle is their growing control of territory and population centres; the Yemeni government’s is its international legal authority.

The economic conflict’s roots trace back to the country’s failed political transition, which began in 2012 and collapsed in the face of the Huthi rebellion in 2014, setting in motion seven years of civil war and foreign intervention. The economic and military conflicts did not progress at the same pace. Some aspects of the former were held at bay during the war’s early phases by an informal, technocrat-led economic truce that helped to protect pre-war economic institutions that remained highly centralised even as, in other ways, the country broke apart. Civil servants in Sanaa engaged with political leaders on both sides of the conflict and the parties quietly allowed the central bank to maintain a level of neutrality. The truce was never meant to be more than a stopgap measure, however, and it did not last.

Since the economic truce collapsed over the course of 2016 and 2017, the economic conflict has become sharper and more entwined with Yemen’s shooting war. Its most visible features are the splitting of the central bank into rival authorities in Sanaa and Aden, a power struggle over control of trade flows and taxation of fuel in particular, and the precipitous drop of the riyal’s value in nominally government-controlled areas. The riyal’s depreciation has pushed the price of imported necessities such as food and fuel out of reach for many people. As a result, Yemen is the site of what the UN says is one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises. By the end of 2021, the war had cost around 377,000 Yemeni lives, according to the UN Development Programme. Of this number, most were killed not by front-line fighting, shelling or airstrikes, but by hunger and preventable disease, the overwhelming majority of them young children and women.

The parties’ tactics in the economic conflict have often backfired. The government’s initiatives to wrest control of the economy from the Huthis have tended to rebound against it, in large part because the Huthis control Yemen’s main population centres and hence its biggest markets. Diplomats have struggled to convince the government of the folly of its actions, in part because the economy is one of the few remaining sources of perceived leverage for President Hadi and his inner circle. Considering what is at stake – its very survival – the government is unlikely to stand down from economic warfare without major concessions by the Huthis, who perceive that they have the upper hand in the conflict and therefore see no reason to compromise. Yet, by delaying a settlement further, the government risks ceding still more ground to the Huthis.

The parties’ economic tactics have bedevilled the succession of UN envoys who since 2015 have been charged with ending the war. For better or worse, their efforts have tended to focus on the political and military aspects of the conflict while viewing the economic conflict as a subplot even when it is fundamentally bound up with core political issues dividing the parties. The Stockholm Agreement, which prevented a battle for Hodeida, skated over rather than resolved important economic issues. More recent efforts to resolve the Marib crisis and Hodeida embargo have similarly stumbled in treating profoundly important proposed economic concessions as “confidence-building measures”.

This approach needs to change. While the economic dimensions of Yemen’s conflict are not the only impediments to peace, it is difficult to imagine the parties reaching a durable military truce if they fail to reach an economic one alongside it. The new UN envoy, Hans Grundberg, who assumed his post in September, is considering how his office can address the economic conflict. He has some useful models to follow. In Libya, for example, the UN envoy’s office initiated a separate track for economic issues that fall within the framework of broader conflict resolution efforts. Grundberg should take a page from this book, establishing a formal track to address the economic challenges that have become interwoven with the toughest political issues that separate the parties. The concrete objective would be an agreement in which the conflict parties pledge to stop working to damage each other economically and to cooperate in the interests of ordinary Yemenis who desperately need both economic opportunity and better services.

In early 2022, the conflict for Marib escalated. Without progress on the economy, Grundberg is unlikely to be able to stop the shooting. Many of the same obstacles to agreement that have dogged mediators in their pursuit of a military ceasefire will encumber their efforts to achieve an economic truce. Even with international support – which outside actors should certainly lend him – the envoy faces an uphill climb. But that climb will almost surely be steeper still without a dedicated effort that allows mediators to better understand and deal with the economic issues that are so fundamentally bound up with the political drivers of Yemen’s civil war. Seven years into this brutal conflict, it is past time to give this task a try.

Amman/Cairo/Aden/Sanaa/New York/Brussels, 20 January 2022

I. Introduction

In September 2014, a coalition of Huthi rebels and loyalists of former President Ali Abdullah Saleh seized Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, after several days of fighting on the city’s outskirts. The fall of Sanaa marked the end of a transitional period that had begun in February 2012, when Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi – Saleh’s successor – assumed the presidency. Saleh had been forced from office following a popular uprising against his corrupt and sometimes brutal 33-year reign. Elected in a non-competitive process, and enjoying international recognition, Hadi was to be a caretaker leader while a National Dialogue Conference prepared recommendations for a constitutional drafting committee in anticipation of fresh elections. But this ambitious program failed. Buttressed by popular frustration with economic conditions and supported by Saleh and his allies, the Huthis took advantage of state weakness to expand their territorial control, until they captured Sanaa itself.

As most of Yemen’s national institutions were in the capital, it seemed that the Huthi-Saleh alliance had taken over the Yemeni state. Certainly, they tried to do so. After taking Sanaa, their combined forces moved to gain control of most of the country’s main population centres, commercial hubs and natural resources.

Six years later, a senior official of the transitional government that the allies had deposed reflected:

They did what you do when you stage a coup. … The Saleh people had run Yemen for three decades, so they knew what was important and where to go to make sure they could finance their operations. … And they almost succeeded.But the Huthi-Saleh coalition failed in its drive to bring the entire country to heel. In February 2015, President Hadi, whom the alliance had placed under house arrest in Sanaa a month earlier, and who resigned in response, fled to the southern port city of Aden. There, Hadi rescinded his resignation, which he said he had made under duress, called for international military intervention to restore his government to power and named Aden the interim capital.

In March 2015, a Saudi Arabia-led coalition launched a military intervention with U.S. support that by mid-year had pushed the combined Huthi-Saleh forces out of most of the south. The UN and foreign powers continued to recognise the transitional government as Yemen’s rightful rulers, allowing President Hadi to lead anti-Huthi Yemeni forces, albeit mostly as a figurehead based outside the country.

In April 2015, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2216, in which it recognised Hadi as Yemen’s legitimate president, called upon the Huthi-Saleh alliance to hand over weaponry and, in effect, surrender, and imposed an arms embargo on Saleh and two Huthi leaders. The two-party framework for negotiations established by 2216 was aspirational at best, even at the time. It is now significantly outdated, not least because the Huthis killed Saleh in December 2017 after the alliance frayed. Armed groups that are not subordinate to either the Huthis or the Hadi government have proliferated since 2015 and the country has been split into multiple zones of military and political control.

Given the significant strengths of the sides the UN engages in talks in Yemen – the Huthis’ control of most national institutions and increasingly dominant military position on the ground versus the Hadi government’s foreign backing and international legal standing – it is not surprising that neither has been able to achieve a decisive political or military victory. To gain an edge, the Huthis, the Hadi government and the Saudi-led coalition all have increasingly turned to economic tools. Over time, their economic interventions against each other, which this report refers to in the aggregate as Yemen’s “economic conflict”, have both complicated efforts to end the shooting war and deepened what the UN has long described as one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises.

This report explores Yemen’s economic conflict and offers recommendations for preparing to address it as part of UN-led peace talks. Blending qualitative and quantitative research methodologies, it is based on around 80 interviews with Yemeni businesspeople, bankers, civil servants and political leaders, as well as regional and international officials, conducted between June 2020 and November 2021. Its quantitative analysis uses district-level control mapping checked against similar data gathered by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); analyses of pricing and currency data collected by the World Food Programme (WFP); and figures collated by a private trade data collection firm. It also draws on work conducted by the Assessment Capacities Project (ACAPS), a humanitarian analysis consortium.

Lastly, it benefits from unpublished work by the International Growth Centre’s State Fragility Initiative. The report builds on Crisis Group’s extensive previous research aimed at ending the Yemen war and blunting its humanitarian impact.

Economic Truce, Economic Warfare

A. Weak Economic Foundations

Already before the war, Yemen’s factious elites were competing over an economy that rested on weak and crumbling foundations.

Economic output relied heavily on dwindling hydrocarbon exports, import-led trade – the country purchased some 90 per cent of its wheat and all its rice from overseas – and services such as banking and telecommunications. To pay for imports and support the Yemeni currency, the riyal, the government relied on foreign currency earned through oil and gas exports and on remittances from Yemeni workers abroad. Oil and gas revenues underwrote a large public-sector wage bill and costly fuel subsidies. This setup fostered corruption, left Yemen in a near-permanent fiscal and monetary crisis, and made the country vulnerable to international commodity price shocks. When oil prices fell on global markets, state revenues plummeted. When they rose, income increased but so, too, did the cost of fuel subsidies, which by 2014 outstripped oil export income.

Against this backdrop, political stability was largely dependent on patronage networks, which formed around a regime that had only tenuous control of national territory and splintered during Yemen’s 2011 uprising.

Regime infighting that year caused an economic downturn and exacerbated unemployment. Yemen’s poverty rate topped 50 per cent by the end of 2011. The main geographic node in this unstable and unsustainable system was Sanaa, with its government institutions. The finance ministry and central bank provided importers with letters of credit, managed hard currency supply to maintain the riyal at a stable exchange rate to the dollar, oversaw the payment of fuel subsidies to a state-run firm that held a near-monopoly on domestic fuel distribution, and managed salary payments.

The private sector, almost exclusively headquartered in Sanaa, was reliant on favourable treatment from political allies in the capital.

Although they had been expanding their territorial footprint for months, the Huthis framed their push to Sanaa in 2014 as a response to the Hadi government’s decision to cut almost all fuel subsidies overnight in August of that year. The Huthis, citing corruption, economic mismanagement and foreign control of policy decisions, launched what they termed a “revolution” against the government of President Hadi, setting up protest encampments in and around Sanaa while launching a military offensive from their base in the northern Saada governorate.

After the Huthis and their allies took Sanaa, they appointed loyalists to oversee work at ministries and the central bank. These new mushrifeen (supervisors) paid particular attention to the finance ministry, which held data on the government’s cash reserves and revenue-generating operations – the state’s financial lifeblood.

” The outbreak of the war with the Saudi-led coalition in 2015 … further buffeted the ailing economy. “

The outbreak of the war with the Saudi-led coalition in 2015, sparked by Huthi-Saleh expansion from Sanaa earlier in the year, split Yemen into several zones of territorial control and further buffeted the ailing economy. Front-line fighting, shelling and airstrikes badly damaged infrastructure and agricultural output.

Oil and gas exports ground to a halt, gross domestic product fell by an estimated 28 per cent in 2015, and the country descended into simultaneous fiscal, monetary and financial crises. In June 2015, financial officials in Sanaa wrote in a note to international institutions that “the fiscal situation is catastrophic!!!”

Yet for all the surrounding chaos, the war did not, at first, cause irreparable fractures in state economic institutions. Technocrats in ministries brokered an informal institutional arrangement between Huthi-Saleh-controlled Sanaa and the Hadi government, which had by that time largely relocated to Riyadh despite naming Aden Yemen’s temporary capital.

The deal aimed primarily to protect the finance ministry and central bank from being politicised and ensure that the economy continued to function. The deal was supported by a World Bank official seconded to the UN envoy’s office in 2014 and other international officials who recognised the risk to the economy of allowing institutions to crumble or fragment. Civil servants in Sanaa remained in direct contact with ministers in the Hadi government, then headed by Prime Minister Khaled Bahah. Who had the authority to issue instructions to staff, and who did not, was opaque, and the setup clearly could not last for long.

But it was not intended to endure: the stopgap arrangements, which officials described as an “economic truce”, were based on the assumption that a political settlement was inevitable and imminent.

This assumption proved mistaken. The war dragged on, and as it did, officials in Sanaa began to speak urgently of the need for emergency measures to prevent complete economic collapse. Central Bank Governor Mohammed bin Humam and his staff – in written correspondence and meetings with President Hadi, government officials, international institution representatives and foreign diplomats – warned from late 2015 onward that hard currency and riyal banknotes were running low.

The shortages risked weakening the currency – thereby reducing the inflow of basic goods and threatening the government’s ability to pay public-sector salaries. They recommended that the bank suspend letters of credit for fuel and sugar imports in order to slow the pace at which it was using up its dwindling supply of hard currency; that the government liberalise the fuel trade by ending the state monopoly and allowing private firms to import and distribute it; and that the bank be authorised to print new riyal notes to make payroll.

Mistrust between the Hadi government and central bank staff in Sanaa also became a growing impediment to managing the economic crisis. Amid UN-led efforts to broker a ceasefire and political settlement in early 2016, the government began to accuse bin Humam of allowing the Huthi-Saleh alliance to plunder the bank and its international accounts to underwrite their war effort. It blocked the bank from printing new riyals by sending a note instructing the Russian firm tasked with printing the bills to cancel the order.

The bank continued to struggle. By mid-2016, it was having trouble paying state salaries. With bin Humam’s term as governor up for renewal in August 2016, the economic truce’s sponsors worried that a policy vacuum was emerging. Bank staff protested that they were working to prevent a Huthi takeover of the institution.

The UN envoy’s office brought bin Humam to Kuwait to discuss the economy on the sidelines of peace talks.

But the government was increasingly hostile to him. Explaining the government position, a government economist noted:

Bin Humam and his office couldn’t guarantee the bank’s independence. The government requested a suspension of payments to the [Huthi-Saleh-controlled] defence ministry at the very least. He said: “Listen, if I suspend the payments to the defence ministry, the Huthis will come over, take over the central bank and arrest my staff”. … The central bank’s leadership was in a very peculiar position.Seeking to sustain the bank’s neutrality, some senior officials in Sanaa, Riyadh and Aden, including Prime Minister Bahah, proposed establishing a coordinating office outside of Yemen under bin Humam or someone else.

By mid-2016, however, Yemeni government officials in Riyadh had also begun discussions with their Saudi and Emirati counterparts about reconstituting the central bank in Aden under new leadership. UN, U.S. and UK officials warned that doing so could prove economically catastrophic because the Hadi government lacked the resources or manpower needed to operate the bank. But they said they remained hopeful that UN-led talks in Kuwait between the government, the Huthi-Saleh alliance and the Saudis would resolve differences between the two sides.

As discussed below, those talks ended without producing a settlement in August 2016.

B. The Saudi Blockade and the UN Verification Mechanism

Control of Yemen’s inbound trade also became caught up in the war during the conflict’s first months. When, in March 2015, Saudi Arabia launched a naval blockade of Yemen’s ports, diplomats scrambled to ensure that food, fuel and other basic goods could still get into the country.

The Saudis said the blockade was meant to stop the Huthis from acquiring Iranian weapons smuggled aboard cargo ships. Foreign officials tried to reassure Riyadh that allowing imports into the Huthi-controlled Hodeida port would not facilitate such smuggling, citing intelligence that showed most weapons were coming into Yemen on dhows, small boats mooring in coves along the coast, rather than cargo vessels. The UN appointed a veteran official to negotiate design of an inspection system for commercial ships docking in Yemen, known as the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism (UNVIM).

This mechanism, which became operational in May 2016, allowed more goods into Hodeida but did not remove all obstacles.

In 2015, Saudi Arabia had created a unit in its defence ministry charged with monitoring maritime and airborne trade entering Yemen, calling it the Emergency Humanitarian Operations Cell. The Hadi government authorised the cell to inspect vessels and detain them in what is known as the Coalition Holding Area, off the Red Sea coast of Saudi Arabia, and to oversee their passage into Yemeni waters once the government had signed off on shipments separately as part of the UNVIM regime. Coalition naval forces under the government’s authority often delayed ships in the holding area and subjected them to intrusive searches even if they had received UNVIM clearances. Businesspeople accused government officials of soliciting bribes in exchange for approval of shipments. Citing regular delays in approvals, the Sanaa-based Huthi-Saleh authorities argued that this tangle of requirements and protocols still constituted a blockade, or siege, of their areas.

C. 2016-2017: Ending the Economic Truce

By mid-2016, as UN-led talks in Kuwait teetered on the verge of collapse, the technocrats’ economic truce had become untenable. In July of that year, the Huthis and Saleh’s pre-2011 ruling party, the General People’s Congress (GPC), announced the formation of a new Supreme Political Council to perform presidential duties in Hadi’s place, as well as a National Salvation Government, including a new finance minister who under usual circumstances would have assumed the position of central bank vice chair.

Days later, the Hadi government’s Aden-based prime minister, Ahmed Obeid bin Dagher, issued a letter to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and major international private and state-run banks, informing them that bin Humam and the Sanaa central bank no longer represented the Yemeni state.

The Kuwait talks ended inconclusively in August.

” With the Huthis taking measures to cement their … status as de facto rulers in Sanaa, the Hadi government responded by seeking to loosen the rebels’ grip on economic institutions. “

With the Huthis taking measures to cement their authorities’ status as de facto rulers in Sanaa, the Hadi government responded by seeking to loosen the rebels’ grip on economic institutions. In September 2016, President Hadi announced that his government was relocating the central bank’s headquarters to Aden and installing as its governor a close ally, Monasser al-Quaiti, who had served as finance minister in Riyadh since 2015.

But the announcement did not translate into tangible changes at first. The Huthis did not recognise the move, and central bank staff at the Sanaa headquarters continued work as normal. Moreover, the government did not initially have access to the bank’s SWIFT system, used to make international transfers. Nevertheless, over time, the government began to staff the Aden branch of the bank and sought to claim control of international accounts and the SWIFT code.

The government said moving the bank to Aden was necessary, in part because bin Humam’s term was expiring, but the decision was made hastily and without planning.

President Hadi offered a strategic rationale, namely, that the move would help to cut funding to his rivals.

A former government official said:

It wasn’t very complicated. They wanted to turn the tables so that they had the money and the Huthis had none, and so that the Coalition wasn’t on the hook to finance them in the future. But there wasn’t a plan in 2016, there wasn’t a strategy beyond that desire, to move the bank.The move also prompted speculation about Hadi’s political intentions. The new governor primarily hired southerners to run the bank in Aden and elevated a number of staff from what had been a local branch of the central bank to senior positions, convincing some Yemenis that he was, in effect, building a southern institution to break away from the north. A central bank official said: “We honestly were unsure ourselves if this was going to be a central bank for the south or for Yemen as a whole”.

In 2017, the new bank started printing riyal notes in a new format, giving rise to additional rumours – propagated by some in the government camp – that it planned to remove from circulation the old currency used by the Sanaa central bank. (Government officials now deny that they ever considered that step.

) The government said the new notes would be used to pay salaries, but it did not publish either figures on how much money had been printed or an annual budget, complicating the task of tracking what it was doing with the notes.

Many, on both sides of the war, came to wonder if the government was trying to fully control Yemen’s monetary policy to the detriment of the Huthi-run economy.

The Huthis in particular accused the government and the Saudi-led coalition of seeking to decimate the economy in order to starve the Huthis into submission. A senior official at the Huthi-run Sanaa Central Bank of Yemen said:

All economic sectors have been targeted by the coalition of the aggression against Yemen. They do whatever they can to destroy the economy in general. The coalition was planning the total economic collapse of the economy and government institutions so we would arrive at a state of hunger and violence.Saudi and government officials deny such claims. But the economy had clearly become politicised and was now more entwined than ever with the conflict.

D. 2017-2018: A Regulatory Vacuum

By early 2017, the Hadi government and the de facto authorities in Sanaa had each taken measures to ease the financial burden of costly pre-war import and currency support mechanisms – in each case by drawing back from certain roles it had played. In August of that year, the government liberalised the foreign exchange sector by halting efforts to defend the riyal against the U.S. dollar by selling hard currency into the local market at set rates, building on bin Humam’s earlier decision to allow the riyal to decline from 215 to 250 against the dollar.

The move protected the bank’s dwindling foreign currency reserves but eroded the influence it had wielded over markets when it was the primary source of hard currency.

The de facto authorities in Sanaa and the government also each announced moves to open up the fuel import sector, hitherto largely monopolised by state companies.

Combined with the central bank rift, which seeded confusion over who set monetary policy, oversaw private banks and regulated money exchangers – tasks the government was ill equipped to do given its lack of skilled staff or presence on the ground – the rivals’ new laissez-faire approach to the financial and import sectors created the perception of a regulatory vacuum.

Yemeni financial institutions and businesses thus became seen as riskier partners for their international counterparts. Foreign banks in particular were already alarmed by the UN arms embargo on Huthi leaders and former President Saleh, which they feared could be a precedent for the U.S. or other countries to impose their own bilateral punitive measures. After the central bank move, they accelerated a process of risk-averse compliance measures, cancelling many Yemeni businesses’ accounts. For this reason, many Yemeni businesses lost access to correspondent banking relationships abroad, which are key to their ability to transfer funds to pay for imports and other associated services.

” With oil exports having collapsed in 2015, Yemen was increasingly dependent on remittances from abroad. “

Moreover, with oil exports having collapsed in 2015, Yemen was increasingly dependent on remittances from abroad, which in turn were subject to regular interruptions due to transfer agencies’ concerns over sanctions and running afoul of money-laundering and counter-terror financing laws.

Remittances and imports are vital to ordinary Yemenis’ survival. With foreign currency in short supply and the international banking sector increasingly leery of doing business with Yemeni partners, informal money transfer networks, known as the hawala system, filled the void. Imports became a crucial cog in the hawala machine, as they could be moved from other countries into Yemen and sold into local markets for cash, effectively sidestepping formal money transfers. Since fuel was the highest-value import item and a dollarised commodity whose price was no longer set by local authorities, and the removal of subsidies had made competing in the local market more profitable, it became a high-demand, transferrable store of value. “Fuel became better than gold”, a Yemeni businessman said.

By 2017, economic battle lines had been drawn around Hodeida in particular. Fuel imports represented a copious and stable source of revenue at the Huthi-Saleh alliance-controlled port.

In the view of government officials, the alliance’s collection of taxes and customs at the port, particularly but not only on fuel, was tantamount to plundering state resources; for their part, the de facto authorities in Sanaa argued that they were simply fulfilling their governing duties. Hadi government officials and the Saudi-led coalition further alleged that Iran was boosting Huthi revenues by sending fuel shipments to Hodeida via the United Arab Emirates (UAE) at low or zero cost, which the rebels could sell in the local market.

The duelling monetary policies of the rival authorities also caused friction.

The deregulation of markets, and delays in the Saudi-led coalition making a promised large dollar deposit at the Aden central bank, had led to a depreciation in the riyal’s value against the dollar.

From early 2017, the fall in the riyal-dollar exchange rate accelerated, prompting tit-for-tat accusations from the rival parties.

The Huthis argued that the devaluation stemmed from the government’s printing of banknotes to fund its budget. The Huthis further argue that from 2017 onward the government was receiving income from customs and fuel exports that could have been used to stabilise the economy but were instead being plundered. For its part, the government accused the Huthis of manipulating the riyal by pressuring traders to sell notes in large quantities in order to artificially depress the currency’s value so that they could profit when it returned to earlier levels. The government also alleged that the high volume of fuel imports into Hodeida were being used to transfer Iranian funds to the Huthis, a claim both the Huthis and Tehran deny.

In reality, both parties were to blame: all these factors and more played a role in accelerating the country’s economic collapse.

E. 2018-2019: Conflicts Converge

Yemen’s economic and military conflicts converged in 2018. In December 2017, the Huthis had killed their erstwhile ally, Saleh, after months of rising internal tensions. Calculating that the Huthis had been weakened by their continuing battles with Saleh loyalists, the UAE announced that it was reinvigorating its year-old military campaign along the Red Sea coast with the goal of taking the port city of Hodeida.

From late 2016 onward, UAE officials had made three arguments for seizing Hodeida, claiming that with it under their control they could prevent Iranian arms smuggling through the port; secure the Red Sea shipping lanes from Huthi and Iranian attack; and be able to disrupt the Huthis’ financing and logistical capabilities. This last point was, in Western officials’ view, a way of suggesting that they would seek to wrest control of imports into Yemen via Hodeida from the Huthis, for whom it provided vital revenue. After the Kuwait talks’ collapse in 2016, U.S. and British military officials, who rated the chances of success of a maritime assault on Hodeida poorly and worried that a battle for the city could deepen the humanitarian crisis, dissuaded the UAE from launching the operation.

In parallel, the government began to discuss other plans to cut off the Huthis from revenues they earned from Hodeida, using its internationally recognised legal status as Yemen’s sovereign authority. It was aided by Saleh loyalists, many of them senior members of the GPC (which as noted above was the pre-2011 ruling party), who left the important roles they had played in the Huthi-Saleh alliance and joined the anti-Huthi camp after Saleh’s death.

Armed with economic expertise and knowledge of how the authorities in Sanaa raised revenues, they proposed a series of initiatives to weaken the Huthis’ revenue collection capabilities and bolster the government’s.

At the same time, the government sought to make itself a more reliable economic player and improve its governance. It increased the number of state salaries it paid, including some in Huthi-controlled territory.

It calculated that a battle for Hodeida, along with better security and service delivery in Aden, would lead Yemen’s major businesses to move their headquarters to the interim capital, where the government could tax their profits. In January 2018, Riyadh announced but held back disbursement of a $2 billion deposit for the central bank in Aden. Government officials began to draft a series of conditions for access to letters of credit paid for through the Saudi deposit.

Combined, a UAE-led takeover of Hodeida, an aggressive push to control fuel imports and remittance flows, and a recapitalised central bank could have dented the Huthis’ ability to finance their operations in Sanaa while burnishing the government’s economic governance capabilities. Some viewed the plan to sever the Huthis’ revenue stream as designed mainly to improve the GPC’s weakened position, rather than to bolster Hadi’s. Yemeni and foreign observers perceived an emergent if brutal economic strategy.

In line with comments from numerous other observers, a Western diplomat working closely on economic issues in Yemen at the time said:

Moving the central bank to Aden was the first move in the economic war, but the real economic strategy was born in 2018. It was much bigger than anything Hadi could have come up with. The banks were essential to this part of the war, and so was Hodeida. You would get the revenues from Hodeida and then [once UAE-backed forces seized Hodeida from the Huthis] have the GPC bankers running things from branches in Hodeida, which is in the north, and move the whole economic infrastructure there.But the economic strategy floundered in the face of events on the ground. The Hodeida offensive did not take place. Amid the uproar over the Saudis’ killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018, and fears of a humanitarian disaster voiced by Crisis Group and many others, the UN and U.S. intervened to stop a battle for the port and city.

Meanwhile, the central bank was unable to get access to the Saudi deposit until nine months after it was announced, also in October 2018, due to bureaucratic wrangling over the technical requirements for disbursal. By that time, the country was in the midst of a full-blown humanitarian and currency crisis.

F. 2019-2020: The Stockholm Agreement and Its Aftermath

- UN involvement

Before the Hodeida standoff, UN Envoy Martin Griffiths, who succeeded Ould Cheikh Ahmed in April 2018, had sought to avoid direct entanglement in economic disputes. He and his senior staff argued that their job was to end the war, not to get caught up in granular disputes over the minutiae of the economy.

But the agreement that he brokered to prevent a battle for the port city made such a stance untenable. In December 2018, Griffiths mediated a deal, the Stockholm Agreement, between the government and the Huthis, whose centrepiece, negotiated during indirect talks in Sweden, was a sub-agreement on Hodeida. The Huthis and the Hadi government committed to a ceasefire around Hodeida and neighbouring Red Sea ports, a redeployment of forces from Hodeida, an enhanced UNVIM inspection regime including a larger UN presence at Red Sea ports, and a new mechanism to collect port revenues and pay civil service salaries via the central bank branch in Hodeida, which the Huthis controlled.

The agreement achieved the UN’s primary goal – preventing a battle for Hodeida – but the text was loosely written and lacking in detail, particularly with respect to the management of revenues generated at the Hodeida port.

The government interpreted the agreement as an assertion of its sovereign authority over Hodeida. Thus, it argued that it had the right to select the local security forces whom the agreement made responsible for securing Hodeida and its environs, and to control the central bank’s Hodeida branch and hence port revenues. The Huthis contended that the agreement stipulated that the existing police and coast guards (largely aligned with them) would remain in place following the withdrawal of rival military forces from Hodeida. The Huthis’ interpretation was closer to the UN negotiation team’s than was the government’s. But the government argued that what the Huthis wanted was an unacceptable violation of its sovereignty, as recognised in UN Security Council Resolution 2216.

In brokering the Stockholm Agreement, the UN necessarily adopted a ceasefire-first approach to mediation on the basis that preventing famine was the absolute priority.

But perhaps because of the urgency of the task at hand, the text of the agreement was light on detail. It treated security and economic provisions as addressing technical problems, to be resolved by mid-level officials through follow-up negotiations. Yet these provisions touched upon the fundamental question of who should have sovereign state authority – the heart of the political conflict. Problems would thus arise when it was time to implement the deal.

Once the Stockholm Agreement was brokered, the UN envoy focused on restarting high-level political talks, leaving the deal’s security and economic aspects to less senior officials to deal with. He and his senior-most political adviser continued to argue that the economy was not within their office’s remit, and that economic disputes would be settled as part of a national political agreement that would come at a much later stage of the mediation process.

Although they had brokered an agreement that dealt directly with the economic conflict, this dimension of the hostilities was clearly of a lower order of priority than, for example, a military ceasefire or political talks, even if it was a barrier to political progress.

In January 2019, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2452, establishing the Mission to Support the Hudayda Agreement (UNMHA) to observe the ceasefire and coordinate force redeployments outlined in the Hodeida provisions of the Stockholm deal.

Although UNMHA was a special political mission with a Security Council mandate, in practice its head reported to the UN envoy and relied upon him for contact with senior political officials among both the government and the de facto authorities. It dealt mainly with military and security officials who needed signoff from these same political leaders to make decisions. Staff from the special envoy’s office, meanwhile, sought to initiate technical talks about a revenue collection and sharing mechanism. But they, too, dealt mainly with technocrats who lacked decision-making power or direct access to senior leaders. Both processes were troubled from the start, as the rival parties sought to litigate the Stockholm Agreement’s meaning. UNMHA staff quickly saw that their efforts to implement the deal would be impotent without renewed political dialogue.

” The UN envoy’s office continued to [be] primarily focused on achieving a political settlement rather than … on questions of economic sovereignty “

Problems with the Stockholm Agreement bled over into other areas. Throughout 2018, the special envoy’s staff had repeatedly attempted to coordinate a face-to-face meeting between the Sanaa and Aden authorities over economic management in the hopes of reintegrating the central bank and restarting national salary payments.

But after the Sweden talks, they were forced by the deal and the parties to narrow their focus to the opaque and contested revenue-sharing provision outlined in the Stockholm Agreement. A meeting held in Amman in March 2019 ended inconclusively after a series of spats over control of the central bank’s Hodeida branch. Still, the UN envoy’s office continued to see its mandate as primarily focused on achieving a political settlement rather than placing greater emphasis on questions of economic sovereignty that were multiplying and becoming ever larger obstacles to peace.

- Wresting control by other means

As international opposition to a battle for Hodeida had become more evident over the course of 2018, the government began to take legal measures to wrest control of the economy by other means, many of them proposed by the GPC economic experts who had split from the Huthis after Saleh’s death. In September 2018, President Hadi issued Decree 75, which called for a newly formed economic committee to approve all fuel imports and for the central bank in Aden to oversee all dollar transactions tied to imports.

The committee also set more stringent criteria for approval of import licences.

Government officials involved with this and other similar decrees argue that they were simply attempting to impose regulatory structures after a period of lawlessness that, among other things, had seen the riyal’s rapid depreciation.

But businesspeople and other economic observers believed the new regulations sought to curtail the operations of Huthi-affiliated traders.

Over the course of 2019, as the government sought to enforce Decree 75, it also introduced Decree 49; the latter required the payment of customs and taxes to the government before shipments entered Yemeni ports, which the Huthis claimed ran counter to Yemeni law.

A series of standoffs ensued over fuel imports into Hodeida. The Huthis pressured importers not to submit applications to the newly formed Technical Office of the Economic Committee, which authorised ships to move into Hodeida from the coalition’s maritime holding area.

The government responded by blocking ships from entering the port even after they had received clearance from UNVIM, unless they followed the new rules.

Following the promulgation of Decree 49, Hodeida’s fuel imports fell sharply, and fuel shortages soon became commonplace in Huthi-controlled areas.

Fuel prices almost tripled in some of these areas, from 7,300 riyals (about $12) to more than 20,000 riyals (about $33) per 20 litres. By October 2019, the coalition was detaining fuel vessels bound for Hodeida that UNVIM had cleared for passage in the holding area but that had not complied with the new regulations for an average of just under 30 days.

In September and October 2019, worried that fuel shortages and price hikes would deepen the humanitarian catastrophe, the UN envoy’s team pressured the government to release some fuel shipments. In November, it negotiated a temporary revenue collection and sharing mechanism. Under the new mechanism, fuel importers were to deposit all customs and tax payments in an account at the central bank’s Hodeida branch; the Huthis were to regularly provide UN-verified bank statements showing the funds remained in the account until such a time as the two sides could reach an agreement on salary payments, which on paper was the main sticking point for both sides.

In return, the government suspended the two decrees’ enforcement. Fuel flowed into Hodeida and prices fell, but the web of requirements governing fuel imports at the port grew more tangled.

As the economic conflict escalated over the course of 2019, the government’s economic strategy – and credibility – was further disrupted by tensions between Hadi loyalists and the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a self-styled government-in-waiting that seeks an independent southern Yemen. The two sides had clashed for several days in the streets of Aden in January 2018. Cooler heads prevailed but only for a time. In August 2019, STC forces fought a week-long battle that gave them near complete control of the government’s temporary capital. The STC encircled but did not enter the central bank headquarters.

Despite Saudi-led efforts to broker a compromise between the two sides, the government subsequently has been unable to spend more than a few weeks at a time in Aden, departing during tensions with the STC and local protesters, while senior bank staff have in many cases chosen to operate from elsewhere in Yemen or even outside the country.

The government no longer controlled (and to this day does not control), in any meaningful sense, the temporary capital it had hoped to make Yemen’s new financial and economic hub.

G. 2020-2022: Riyal Ban, Marib Battle

Hopes that the UN mechanism would resolve the fuel standoff, or that a Huthi-Saudi back channel that reopened in September 2019 would signal the beginning of the end of the war, were soon dashed.

In December 2019, the authorities in Sanaa reintroduced a ban on new riyal notes printed by the central bank in Aden, delivering a blow to the economy in government-controlled areas.

The move came as Saudi Arabia’s $2 billion deposit with the Aden bank, the government’s principal tool for combating the currency’s depreciation, began to dwindle, and the riyal began to lose value against the dollar in government-controlled areas.

Government officials had been hopeful that Riyadh would deposit more funds at the bank, which might have helped prop up the currency, but that did not happen. Media reports that the first tranche of currency had been mismanaged and an anti-corruption drive in the kingdom that ensnared senior Saudi military leaders involved in Yemen, among others, dampened Saudi interest in providing more funds to the government.

While nominally government-run areas made up more of Yemen’s overall territory, the overwhelming majority of the country’s population – more than 70 per cent – lived in Huthi zones of control. The Huthi ban thus essentially concentrated the new bills the government had printed since the beginning of the war in these much less populous areas, oversaturating the local currency markets that were starved of hard currency with riyals. The supply mismatch acted as an accelerant to the riyal’s decline in government-controlled areas.

A military escalation in the north soon followed. In January 2020, skirmishes blew up into pitched battles between the Huthis and the government and its local allies in three northern governorates, al-Jawf, Sanaa and Marib. By March, the Huthis had seized al-Hazm, al-Jawf’s provincial capital, and begun to push east toward Marib city, the government’s last urban stronghold in the north, and nearby oil and gas facilities.

As the fighting intensified, the UN personnel who might otherwise have conducted face-to-face diplomacy had been grounded by the coronavirus.

” A victory [in Marib] would … deprive the government of significant funds and boost the Huthis’ credibility among the population. “

In February 2021, the rebels stepped up their campaign in Marib and neighbouring governorates, and in September they started tightening the military noose around the governorate after seizing territory in its south.

A victory there would both provide supplies of fuel, electricity and revenue, and also, in the view of some Sanaa officials, allow them to export oil from Marib to a terminal at Ras Issa, north of Hodeida.

It would also deprive the government of significant funds and boost the Huthis’ credibility among the population under rebel governance at Hadi’s expense.

Overlap between the military and economic conflicts now became yet more significant. In February 2020, the Huthis stopped providing statements from the Hodeida central bank branch, later saying they had withdrawn funds to pay public-sector employees half their salaries amid a breakdown in negotiations over a salary payment agreement.

At the same time, the rebels reportedly purged remaining unaffiliated staff from senior bank positions, turning it into an entirely “Huthi” institution in the eyes of many officials, a charge the Huthis deny.

In response, from June 2020 onward, the government intermittently halted approval for fuel shipments entering Hodeida, causing a steady decline in fuel entering the port and, as a result, a sharp price rise in Huthi-controlled areas despite falling global prices.

UN diplomatic intervention led to stop-start fuel shipment clearances in July and October-December 2020. But fuel import volumes at Hodeida continued to decline anyway as traders sought to avoid further disruption by shipping fuel to other Yemeni ports.

At the same time, infighting among the anti-Huthi ranks continued to hinder the government in imposing its will on the economy in areas under its nominal control. In April 2020, the STC declared self-rule in Aden, and surrounded the Aden central bank headquarters, although it did not enter the building. Two months later, the STC reportedly seized some 64 billion riyals in banknotes (more than $250 million at the exchange rate at the time) from bank authorities who were transporting them from Aden port to the central bank. Saudi Arabia again intervened, to prevent the bank’s takeover by the STC, stationing its forces around the Aden bank’s perimeter. In January 2021, the government again stopped most fuel shipments following a Huthi attack on Aden airport, in which a missile nearly struck the plane carrying Prime Minister Maen Abdulmalek Saeed’s newly formed cabinet.

By mid-2021, fuel imports into Hodeida had slowed to a trickle.

Since early 2021, the economic and military conflicts have become yet more intertwined. In February and then again beginning in September, the Huthis made significant territorial gains in Marib and neighbouring governorates, getting closer to Marib city and the nearby Safer oil and gas facilities as well as a connected power plant. By mid-November, they controlled most of twelve of Marib’s fourteen districts. As the Huthis moved deeper into the governorate, they became more vocal in arguing that life under their rule was superior to other parts of the country, fairer and more stable. They claimed that the government’s local allies, particularly Islah, a Sunni Islamist party, were looting oil, gas and electricity, which the rebels said should be shared among all Yemenis, with the sharing controlled by the Huthis’ de facto authorities.

They also burnished their reputation for responsible economic governance, for example by hastening to stabilise the riyal’s value in areas they had captured.

The government and their Saudi allies meanwhile sought new forms of economic leverage with the Huthis. In late 2020 and early 2021, officials from both governments lobbied the outgoing Trump administration to designate the Huthis a Foreign Terrorist Organization. In January 2021, in one of the administration’s last acts, it obliged.

The designation’s main effect would have been economic, forcing U.S. businesses to halt all commercial relationships with counterparts working in Yemen, diminishing trade flows and driving commodity prices up further. It would probably have achieved through legal means what the government and the coalition had earlier sought to do militarily – cut off Hodeida – but given businesses’ risk aversion would also likely have curtailed trade to Aden, Mukalla and other nominally government-controlled ports, cutting off the government’s nose to spite its face. In any event, the new U.S. administration of President Joe Biden quickly reversed the decision.

The government, meanwhile, has struggled to cope with an escalating economic crisis in its own areas. But the government appears to have remained more focused on wresting control of the economy from the Huthis than on improving governance in the territory it controls. Since January 2021, protests have roiled Mukalla, Aden, Ataq and Taiz – the major cities under the government’s control apart from Marib – over living conditions. The riyal fell to new lows against the dollar in Aden in December 2021, reaching a 1,700 to one exchange rate, despite the government having secured access to about $100 million held at the Bank of England and several hundred million dollars of IMF funding. The government responded by shuttering local exchange firms and asking foreign banks to freeze cooperation with a major Sanaa-based bank on the grounds that it refused to share data with Aden, and by auctioning limited amounts of hard currency on the local market. Aid officials saw the bank move in particular as disruptive to aid flows and an effort to strong-arm the UN into routing money via the Aden central bank.

In early 2022, the government’s situation appeared to improve and the Huthis’ to worsen. Hadi’s appointment of a new governor and board at the central bank, and rumours that a new deposit might soon be forthcoming from the Gulf states, led to a temporary rally in the riyal-dollar exchange rate to less than 1,000 riyals to the dollar, although by mid-January the rate had again sunk below 1,300 to one.

Around the new year, the Huthis were pushed out of Shebwa governorate by coalition-backed forces, the first time they had lost territory since they began their advance on Marib in 2020. A Huthi-claimed drone attack on Abu Dhabi, finally, drew international ire and talk of new sanctions against the rebels.

But these developments have not yet changed the war’s overall trajectory and are more likely to make the rivals entrench their positions in the economic conflict than seek compromise.

III. Understanding the Impact of Economic Conflict

A. The Conflict’s Fallout

Falling income was the main factor depressing ordinary Yemenis’ purchasing power during the war’s early years. As the economy contracted, many Yemenis lost full-time jobs and sought irregular alternative work, leading to a fall in household incomes and placing stricter limits on budgets for food and other necessities.

A series of additional shocks have since pushed basic goods out of reach for many Yemenis. Among these are the cessation of many public-sector salary payments, natural disasters and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The combined hunger-humanitarian crisis does not result from a lack of basic goods, such as food, clean water and medicine, which have been generally available, but from most people’s inability to pay for such goods because of lower incomes and higher prices. Rising prices have been the primary problem since 2018. The economic conflict between the government and the Huthis has been an important contributing factor to the resulting increase in living costs. The World Food Programme estimates that the cost of the basic food basket purchased by an average Yemeni family has increased by more than 170 per cent over the course of 2020 and 2021 in government-controlled areas while increasing by 40 per cent in Huthi-held territory.

- The currency split and its effects

The economic conflict’s most visible effect is the growing divergence in the riyal’s value in different parts of Yemen, which has in turn affected the price of basic goods like wheat and oil. This divergence was triggered by the above-referenced December 2019 Huthi ban on government-printed new-format banknotes. In effect, the move split the country into two economic zones: Huthi-held areas, where “old” riyals are the main currency available; and territory under the government’s nominal control where “new” banknotes printed by the Aden central bank have circulated.

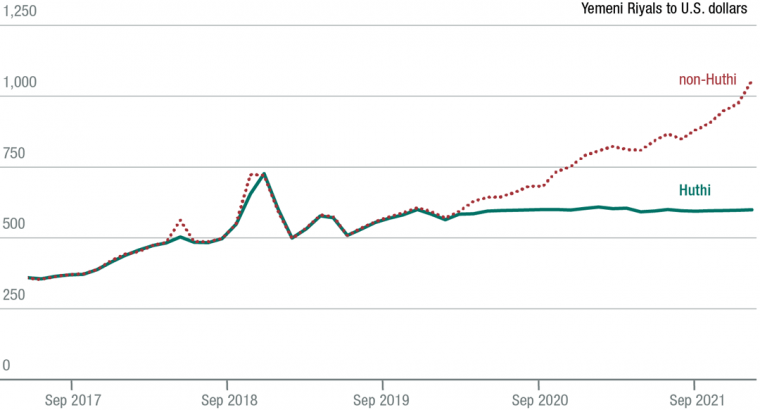

As Figure 2 shows, the riyal functioned as a single currency in both the Huthi and non-Huthi-controlled economic zones before January 2020. But as noted above, by November 2021, $1 traded for almost 1,500 “new riyals”, while the U.S. dollar traded at less than 600 “old riyals” in Huthi-controlled areas. Overall, the riyal has depreciated by about 64 per cent against the dollar since January 2015 in the Huthi-controlled economic zone, and by more than 80 per cent over the same period in nominally government-controlled territory.

As mentioned above, the divergence in the value of riyals in the two zones derives in part from mismatched supplies of local currency and foreign exchange in those zones after the Huthi ban. Foreign currency has consistently been available in greater supply in Huthi-controlled areas than in the rest of the country. Most major banks, businesses and money changers are headquartered in Sanaa, the country’s historical commercial hub, as are UN agencies and most major international non-governmental organisations, which transfer hundreds of millions of dollars per year into Yemen to fund their operations. As a result, most of the country’s hard currency trade still moves through Sanaa, and businesses with foreign holdings are subject to Huthi oversight. The Huthis’ principal financial challenge since 2019 has been a liquidity crunch – their authorities lack the physical notes required to keep the economy in their areas running efficiently.

The government’s monetary challenges are the mirror image of the Huthis’. Growing income from oil exports and domestic oil and gas sales, and the now-exhausted 2018 Saudi $2 billion deposit, have proven insufficient as sources of foreign currency to cover even the modest volume of imports the government underwrites with letters of credit. Following the Huthi ban on newly formatted riyals, areas under the government’s nominal control have also suffered from oversaturation of new banknotes. Making matters worse, to pay salaries and cover operational costs, the government has printed what some of its officials estimate is more than 3 trillion riyals in new banknotes since 2016, a doubling of the money supply compared to January 2015, when the central bank last issued money supply data.

The Huthis claim that the real figure is 5.32 trillion riyals, which would be a tripling of total money supply. The rebels point to the government’s money printing both to explain the riyal’s decline and to justify their ban on the new notes, arguing that the new bills are part of a plot to “destroy” Yemen’s economy.

The government, in turn, blames the Huthis for the riyal’s decline in the areas it controls and argues that it had no choice but to print the new bills in order to pay civil service salaries. It has repeatedly sought to shutter money exchanges it believes are working with the rebels to profit by pushing down the currency’s value in areas they hold.

While there is likely truth to accusations of currency manipulation, the decision to fund the budget by printing new format bills, in particular, along with economic mismanagement, weak regulation and a general decline in economic output have played more important roles.

Indeed, confidence in the government’s abilities as a monetary authority has fallen since the central bank move and the Saudi deposit.

Allegations that the government mismanaged the deposit, including a UN Panel of Experts report that alleged money laundering (the findings of which have since been placed under review), have further damaged the government’s credibility. As a result, many Yemenis are trying to dispose of unstable new banknotes, further weakening the currency.

The government’s appointment of a new central bank governor in December 2021, accompanied by rumours that Riyadh planned on making a new multibillion dollar deposit to the central bank, helped temporarily boost the riyal’s value in December 2021 to around 1,000 riyals to the dollar.

Absent a new deposit and meaningful reform within the bank, however, the reprieve is likely to prove temporary.

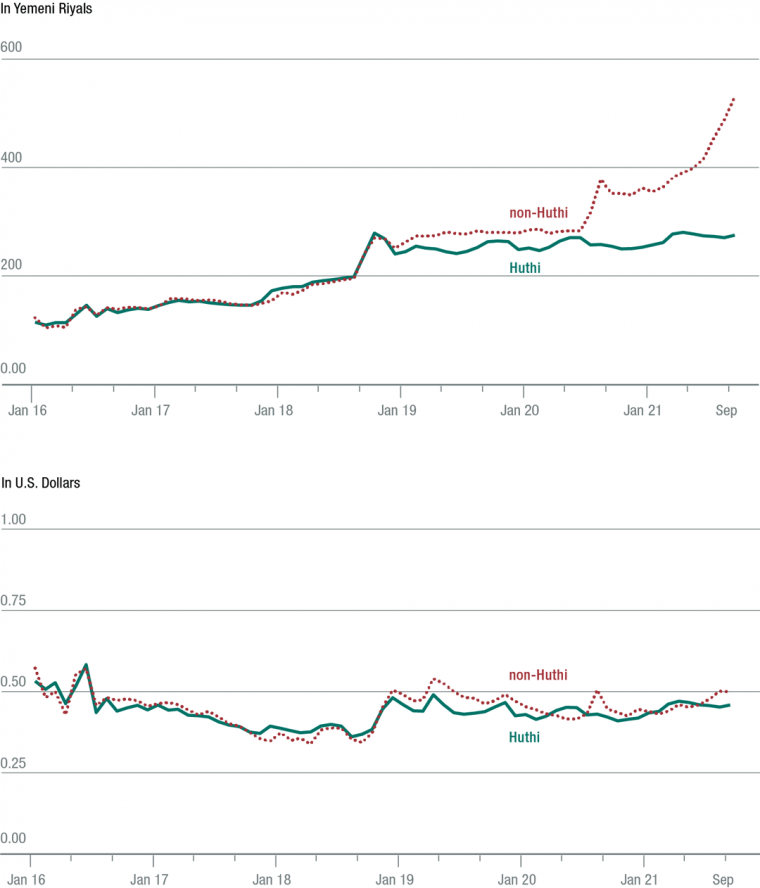

- Wheat prices

Changes in the price of wheat, more than 90 per cent of which is imported, show the impact of the central bank split on ordinary Yemenis. Consumers buying wheat in Huthi-controlled areas paid 4 per cent more in riyals in June 2021 than in November 2019, just before the currency split in two. But riyal wheat prices increased by 49 per cent in government-held areas during the same period. While four factors could contribute to rising wheat prices – reduced supply, higher global prices, profiteering and the depreciating riyal – the last appears to be the most important.

The figures below illustrate the evolution of wheat prices in government-controlled areas. Before the Huthi ban on the new riyal note, local riyal-denominated wheat and flour prices largely moved in lockstep (Figure 3a). Since the ban, wheat prices have risen more sharply in areas under the government’s nominal control than in those held by the Huthis. Wheat flour changed hands in government-held areas at a 22 per cent premium over its price in Huthi-controlled areas in April 2021. Prices have diverged in nominal riyal terms because of the currency’s depreciation from late 2019. When market prices are converted back to dollars using local exchange rates that account for the different valuations of the riyal (Figure 3b), they continue to move roughly in unison and in line with market prices.

That is little comfort to ordinary Yemenis in government-controlled areas, however, whose buying power in riyals has been badly affected by the currency’s decline in value.

Wheat prices by control actor World Food Programme Price Data

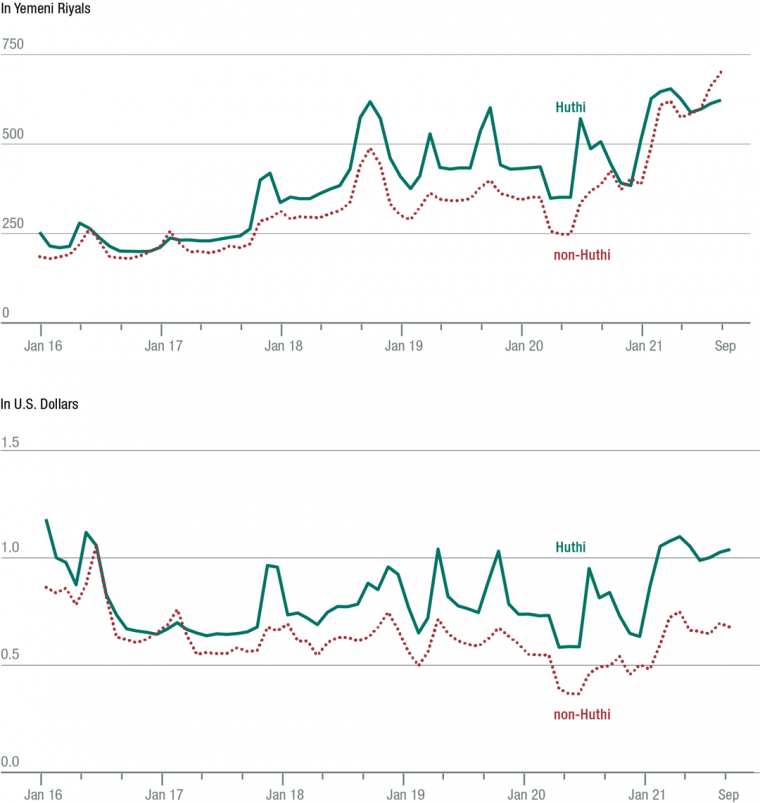

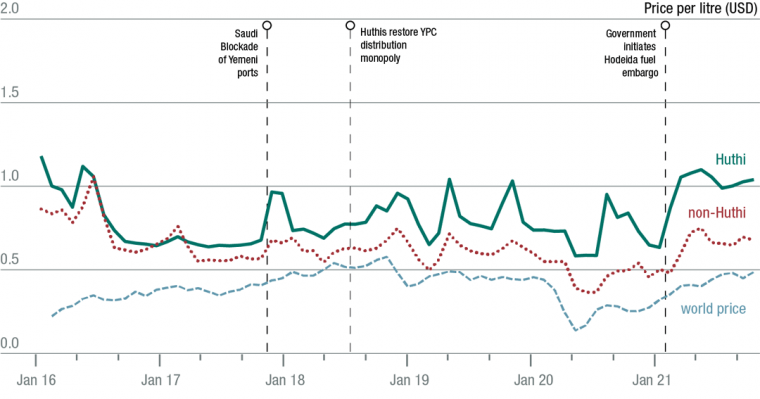

Fuel prices

After spiking in the war’s early days, fuel prices normalised in 2016 but have risen since early 2017. Unlike wheat, fuel pricing was divided along lines of territorial control long before the Huthi currency ban. Whereas food import and distribution networks, which are operated mainly by private-sector actors, remain to this day tightly integrated at the national level, the historically state-run fuel supply chain fragmented down lines of territorial control early on.

Also unlike wheat, the currency’s divergence has served to mask – rather than highlight – the differences in pricing in the two economic zones. Riyal diesel prices have been significantly higher in Huthi-held areas since late 2017, with the gap growing consistently from early 2018 onward, coinciding with the Hodeida offensive and the battle over legislative control of fuel imports and currency. It appeared to close somewhat in riyal terms in 2020 and 2021 (Figure 4a), due to the currency’s depreciation in government-held areas, but dollarised prices rose significantly in Huthi-controlled areas during this period. When diesel prices are converted to dollars (Figure 4b), prices in Huthi-held areas have risen 34 per cent since January 2018, but prices have fallen by 5 per cent in non-Huthi-controlled areas (versus a 10 per cent increase on international markets over the same period).

Traders, businesspeople and Huthi and government officials offer a range of explanations for this growing gap. The Huthis argue that higher prices in their areas are driven by shortages because of the coalition and government’s restrictions on fuel imports at Hodeida port (widely referred to as the fuel embargo), rising shipping costs and demurrage fees imposed on coalition-held vessels, along with double taxation and transportation costs for the growing volume of fuel that first enters government-held areas and is later transported to Huthi-controlled territory overland. The government and its allies claim that there are no shortages in Huthi-held areas and that higher prices stem from Huthi profiteering, a charge the Huthis deny.

Each side appears to be partly correct. Imports into Hodeida in 2020 represented around 35 per cent of Yemen’s diesel and motor gasoline supply, and 32 per cent of heavy fuel oil imports, a lower proportion of the total than in the war’s early days when more than 50 per cent of all fuel entered via Hodeida. By October 2021, the volume of fuel imports entering Hodeida had halved compared to the same month four years earlier. Just 17 per cent of Yemen’s fuel imports came into Hodeida in October 2021, compared to 43 per cent in October 2017, and the proportion was even lower earlier in the year.

This change has resulted from some re-routing of fuel and several short but sharp interruptions of delivery from Hodeida; these shocks to the supply chain can only have exacerbated fuel scarcity and therefore pushed up pricing in Huthi-controlled areas.

Yet the government is correct in arguing that, until 2021, trade disruptions around Hodeida were limited; moreover, total fuel inflows to all Yemeni ports increased over the course of 2020 as importers rerouted shipments to nominally government-controlled Aden and Mukalla ports. They were higher in the first ten months of 2021 than the same period in 2019, which should have eased the pain of disruptions at Hodeida.

It also seems that the Huthis themselves were responsible for some fuel shipment delays at Hodeida: during August and September 2019, the Huthi authorities at the port held ships in anchorage for an average of almost eleven days in what some traders claim was a rebuke to importers who were complying with government regulations.

Statistical analysis of territorial control and diesel prices suggests that, when all other factors are held equal, Huthi control of a district is associated with a 67 per cent increase in the cost of diesel in dollar terms, compared to what the price would be in the same district if controlled by the government or other local actors.

Yet an examination of monthly fluctuation in fuel prices in key Huthi-controlled markets casts doubt on the Huthi claim that the cost differential is purely due to shocks to the Hodeida fuel supply. While such a shock appears to have caused fuel prices to jump in Sanaa during the initial naval blockade in 2015 and then during a short November 2017 supply interruption caused by an announced Saudi blockade of Hodeida, there was a persistent if much narrower gap between prices in Huthi-controlled and other areas of the country throughout periods when there were no such blockade-induced shortages (Figure 4).

In general, high fuel costs in Huthi-controlled areas appear to result from a combination of factors, of which the embargo is only one. These include higher global prices, the riyal’s depreciation, supply disruptions because of the embargo, double taxation (because fuel is being taxed at the port of entry and then at Huthi-controlled inland customs points), higher transport costs and, more than likely, Huthi profit seeking through increased retail prices.

B. The Hodeida Strategy and Its Failings

The Hodeida fuel embargo has brought some financial and other benefits to the government, generating relatively small amounts of customs revenue and forcing the Huthis to depend on supply lines traversing territories its rivals control. At the same time, it is also demonstrably not helping weaken the Huthis financially or economically; it is most visibly rebounding on ordinary Yemenis. But the government, rightly or wrongly, believes that the Hodeida embargo provides it with much-needed leverage over the Huthis, even as its own international image, and that of Saudi Arabia, is increasingly tarnished by what appears to be the collective punishment of the twenty million or so Yemenis living under Huthi rule.

Imports entering Hodeida declined over the course of 2021 as the result of both government regulations on imports and the fuel embargo. On average, Hodeida accounted for 8 per cent of Yemen’s fuel imports in the first ten months of 2021, a sharp decline from previous years.

Ports under the government’s nominal control, principally Aden and Mukalla, benefited from the Hodeida decline. By October 2021, Aden accounted for more than 60 per cent of all fuel entering Yemen. The government earned 100 billion riyals from duties levied on fuel in the first six months of 2021, according to a senior government official. At local exchange rates, this sum would be equivalent to about $100 million, or $16.6 million per month, and should net the government roughly $200 million for the year from these ports. The sum compares favourably to the 120 billion riyals the government says it earned from fuel imports in the entirety of 2020. Government income is now similar to what Hadi officials believe the Huthis earned from fuel taxes and customs at Hodeida port in 2019 and 2020.

But the victory is likely hollow, as it is unclear how much of this income accrues to the government, given that the Aden and Mukalla ports are controlled by local forces that in the past hung on to local revenues.

Moreover, as a former government official noted: “I doubt that either a few weeks without fuel or $200 million a year is going to change the course of the war. It’s a small victory at a big political cost”.

” The [Hodeida fuel embargo] has not damaged the Huthis operationally … the more isolated Huthi areas are, the more influence the group has over the local economy. “

Furthermore, the embargo has not damaged the Huthis operationally, in large part because fuel appears to be flowing into Huthi areas despite the falling volume of imports to Hodeida. Since it began, the Huthis have made significant territorial gains.

In 2020 and 2021, a number of allegedly Huthi-affiliated fuel importers began to bring in quantities of fuel via nominally government-controlled ports at Aden and Mukalla.

Traders and local merchants report seeing large volumes of fuel being transferred from government-held ports to Huthi-controlled areas. Because fuel prices are higher in the Huthis’ economic zone and the old riyal is largely stable there, merchants in government-held areas, where prices are lower and the currency is less stable, have a strong incentive to sell fuel into Huthi-controlled areas.

Nor is the embargo hurting the Huthis’ financial bottom line. Senior officials in Sanaa say customs, tax and other revenues are largely unchanged in 2021 compared to 2020.

The government’s focus on customs revenues fails to take into account how the Huthis make money. The rebels’ economic power increasingly derives from controlling the country’s main population centres, as well as their ability to control and set prices in local markets. Huthi-controlled areas are home to around 70 per cent of the country’s population (10 per cent in Sanaa alone), if not more, and hence its major markets. Moreover, the Huthis operate something akin to a police state in northern Yemen, exerting strong control over locals including businessmen. This degree of control over their areas allows the Huthis to regulate prices in local markets in a way the government cannot match.

A Yemeni researcher characterised the Huthis’ zone of control as a “walled garden”, noting that ironically the more isolated Huthi areas are, the more influence the group has over the local economy, and the greater freedom it has to extract money via taxes and sales of goods like fuel at a markup.

This control has also allowed them to set prices for fuel to their benefit. In July 2018, the Huthis reversed their above-referenced earlier liberalisation of fuel markets, ending the private sector’s role in selling fuel to consumers. The Huthi-controlled Yemen Petroleum Corporation, restored as the sole authorised distributor in Huthi areas, began paying importers a set price for fuel shipments arriving at Hodeida and internal customs points. It sells the fuel at its own gas stations.

The Huthis also play an important role in setting prices in a grey market that operates alongside formal state-run fuel stations. Grey market vendors who would not be able to operate without the Huthis’ tacit approval maintain supply at informal locations during shortages, selling fuel at significantly higher prices than are charged at state-run fuel stations. As a result, the Huthis now control, and profit from, each link in the fuel supply chain.

Since restoring the Yemen Petroleum Corporation’s fuel distribution monopoly, the Sanaa de facto authorities have generated more revenues from selling fuel directly to consumers than from customs duties, taxes and other fees levied at Hodeida combined.

During this period, the dollar margin between global fuel prices and the cost at Huthi-controlled gas stations has widened (Figure 5). Conservatively, the Huthis earned around $524 million from taxes and other fees on fuel and point-of-sale revenues for diesel and gasoline in 2020. This amount is more than half of all revenues the Huthis reported collecting in 2019. The bulk of Huthi fuel income in 2020 and 2021, in other words, likely came not from taxes and fees at Hodeida, but from their control of the supply chain and sales via the Yemen Petroleum Corporation and the parallel market.

Huthi officials and supporters deny that their side has artificially inflated prices in the areas the group controls, citing transportation costs and double taxation as explanations for the price hikes. But the Huthis’ account of the fuel price dynamics in their areas does not add up entirely. Even when these factors are accounted for, at a minimum the Huthis have been able to maintain an income from fuel in 2021 similar to 2020 despite the Hodeida embargo, negating its effects. Using the same estimates above, which account for transportation costs and double taxation, Huthi revenues from diesel and gasoline imports and sales were $219 million amid rising prices in their local market in the first four months of 2021. If the Sanaa authorities were to sustain similar revenues through 2021, they would earn an estimated $657 million over the course of the year, a $153 million, or 29 per cent, increase over 2020.

” In a war that is often fought through narratives, the Huthis have been able to come out on top by telling a story of victimhood. “

Thus, by disrupting supply into Hodeida, the government did little to benefit itself financially and made itself the scapegoat for supply shortages, even if they were partly manufactured by the Huthis, and price hikes that were not in fact wholly its fault. In a war that is often fought through narratives, the Huthis have been able to come out on top by telling a story of victimhood. At the same time, Huthi income may well have increased as a result of its actions in the face of the Hodeida embargo. The government now finds itself in a bind: if it allows trade to flow freely through Hodeida, the Huthis will likely benefit economically while cutting the cost of living in its areas, selling more fuel imported via Hodeida (albeit at a lower margin, if prices are cut to mollify the local population). But if it sustains the embargo, the Huthis can make large sums of money through the arrangements they have created in response, while blaming the government for higher prices as its international image is further tarnished.

C. The Government’s Weakening Position

On the other side of the Huthis’ garden wall, the situation in territory nominally controlled by the government is in deep disorder and may deteriorate further because of the Hodeida embargo and the Marib fight.

The combination of fuel shortages, the currency crisis and worsening humanitarian conditions is deepening divisions among anti-Huthi elements. Fuel and electricity shortages combined with a collapsing currency and the resulting skyrocketing cost of living in Mukalla, Shabwa, Aden and Taiz have led to sustained and often violent protests against government economic mismanagement. The STC has accused the government of waging a “war of services” in its areas, deliberately making conditions unbearable as a way to undermine its cause.

Protests by pro-independence southerners over the declining economy and a lack of services have in turn precipitated violence between government-aligned forces and STC supporters.

Government authorities have tried to stabilise the situation but to little avail. In October 2021, the central bank in Aden initiated new measures to slow down the riyal’s decline, including by suspending the work of exchange companies and releasing new banknotes into the market. But continued volatility sparked widespread protests. Crowds protesting the currency’s decline in Taiz, where the government has previously enjoyed some support, called for President Hadi to be removed.

Food insecurity also continues to rise. According to the World Food Programme, a similar proportion of the population in Yemen’s two economic zones, just under 40 per cent, were not getting enough to eat in August 2020. By November 2021, this percentage was largely the same in Huthi territory and had risen to 48 per cent in non-Huthi areas.