Hargeisa’s sharp rebuke of the Turkish president for remarks made in Ethiopia further exposes how Israel’s recognition of the self-declared republic has unsettled alliances across the Horn of Africa.

Somaliland’s government has hit back at Turkiye’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, accusing him of meddling in regional affairs after he used a speech in Ethiopia to condemn Israel’s recognition of the self-declared republic.

Analysts say the episode highlights just how crowded and fragile the Horn has become.

The Red Sea shipping corridor is under strain, with global trade increasingly exposed to regional shocks. Gulf states are competing for leverage along their shores, investing in ports and security partnerships.

Israel is seeking strategic depth at a time of heightened regional tension. Turkiye has embedded itself as a central security and economic partner in Somalia, where it trains forces, builds infrastructure and backs Mogadishu’s claim to territorial unity.

Somaliland, long on the margins of international recognition, now finds itself at the heart of a much larger contest over influence, access and legitimacy in the region.

Why Hargeisa is angry

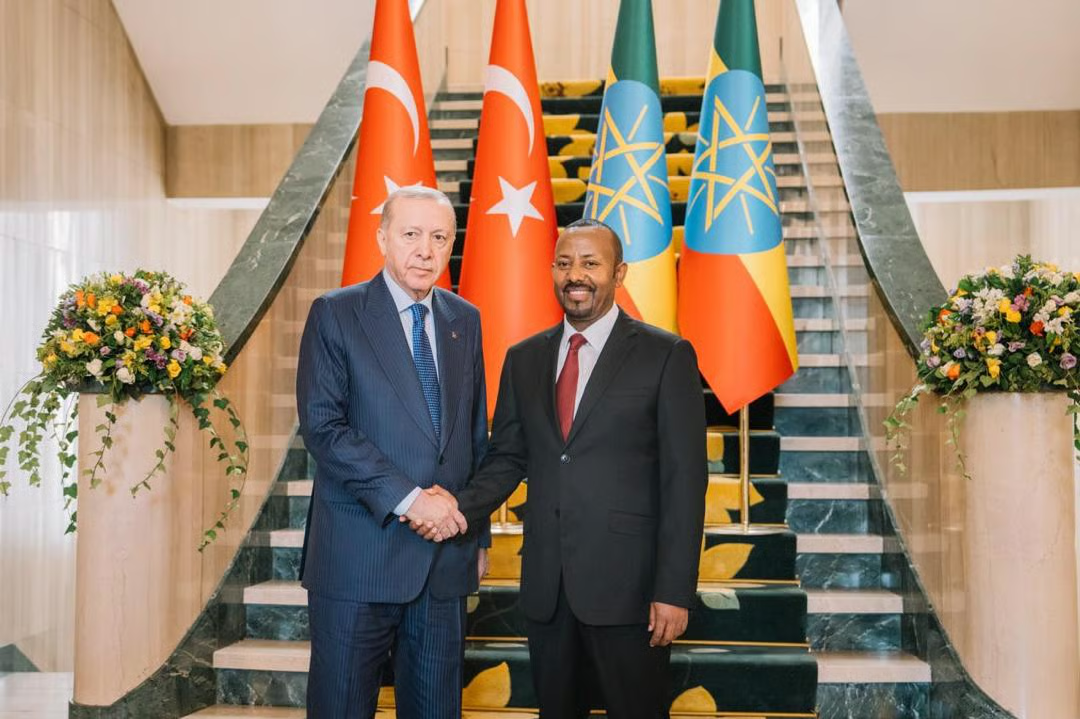

During Tuesday’s official visit to Addis Ababa, Erdogan criticised Israel’s decision to formally recognise Somaliland as a sovereign state, arguing at a joint press briefing with Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed that the move “would benefit neither Somaliland nor the Horn of Africa”.

Warning against introducing new tensions into an already fragile region, the Turkish leader also stressed that regional problems should be resolved by countries within the region, not shaped by outside powers.

For Somaliland, that framing cut deep. In a sharply worded statement issued Wednesday, the government said Erdogan’s remarks amounted to “unacceptable interference aimed at discouraging relations between Somaliland and regional partners”.

It insisted that foreign policy decisions of states in the Horn of Africa must be determined by the region’s own governments and peoples, warning that “external rivalries” should not be extended into the region in ways that risk undermining stability and cooperation.

It called on Turkiye to refrain from taking positions that “inflame regional tensions”, adding that “Somaliland’s outreach to regional and international partners, and its pursuit of recognition, remain peaceful, lawful, and firmly grounded in the democratic aspirations of its people.”

Muhammad Abdi Duale, Somaliland analyst and founder of Hargeisa-based Horn Diplomat media, says Erdogan’s defence of Somalia’s territorial integrity glosses over a crucial historical distinction.

“Somaliland is not a secessionist project born in 1991,” he argues.

“It first became independent in June 1960 and was recognised by more than 30 countries before voluntarily entering into union with the former Italian Somalia.”

According to Duale, that union was never properly cemented through a fully ratified legal framework.

When the Somali Republic collapsed in 1991, Somaliland did not splinter from a functioning state but “reclaimed a sovereignty it had previously exercised.”

That difference, he insists, matters under international law.

…unacceptable interference aimed at discouraging relations between Somaliland and regional partnersDuale also pushes back against the suggestion that recognition would destabilise the region.

For more than three decades, he notes, Somaliland has held elections, overseen peaceful transfers of power and maintained relative internal security without foreign troops on its soil.

“In a region often defined by fragility, Somaliland has been an outlier for stability,” he says.

Turkiye is entitled to its diplomatic position, Duale concedes. However, he argues, it is “neither legally precise nor politically helpful” to frame Somaliland’s case as a breach of territorial integrity.

In his view, prior sovereignty, the principle of self-determination and sustained institutional continuity together form the backbone of Somaliland’s claim.

“Somaliland’s pursuit of recognition is peaceful, lawful and grounded in history,” Duale says. “No external pressure can erase that history.”

Israel’s move

On 26 December, Israel became the first UN member state to officially recognise the Republic of Somaliland as an independent country, opening the door to formal diplomatic relations and cooperation in sectors ranging from agriculture and technology to trade and security.

In Tel Aviv, the decision was presented as part of Israel’s broader push to build new partnerships with strategically located states, an extension of the Abraham Accords logic of widening diplomatic circles.

But geography explains why the move matters. Somaliland’s coastline stretches along the Gulf of Aden, near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, one of the world’s most critical maritime chokepoints linking the Red Sea to the Indian Ocean.

Somaliland’s outreach to regional and international partners, and its pursuit of recognition, remain peaceful, lawful, and firmly grounded in the democratic aspirations of its peopleWith Houthi-linked attacks disrupting shipping, and regional waters increasingly militarised, Israel gains a potential partner overlooking vital sea lanes.

“This calculus has intensified amid Red Sea insecurity, notably Houthi-linked attacks on international shipping tied to broader Middle Eastern conflicts,” according to a report from the Robert Lansing Institute for Global Threats and Democracies Studies.

“Israel is seeking allies with strategic locations to protect its interests and maintain secure sea lines of communication.”

That is precisely what unsettled others. Somalia’s federal government denounced the recognition as a direct challenge to its sovereignty.

The African Union warned about the precedent. Turkiye, Egypt and Djibouti all pushed back. For them, the issue is not just Somaliland, but the risk that the Horn’s delicate political balance could tilt further under the pressure of outside alignments.

Turkiye’s Horn strategy

For more than a decade, Turkiye has quietly built one of the deepest foreign footprints in Somalia:

Major infrastructure projects in Mogadishu

Its largest overseas military base

A 2024 defence and economic cooperation agreement

Mediation between Somalia and Ethiopia under the ‘Ankara Process’Ankara presents itself as a stabilising actor and a defender of Somali territorial integrity.

As a result, Israel’s recognition of Somaliland risks upsetting the regional balance and potentially eroding Turkish influence in Mogadishu.

READ MORE Turkiye in Africa: Trade, security, and complex Ethiopia-Somalia mediation

Erdogan’s remarks in Addis Ababa were therefore not only about principle. They were also about positioning.

The Gulf dimension

The backlash against Israel’s recognition quickly spread across the Arab world.

Saudi Arabia reaffirmed its support for Somalia’s unity and rejected what it described as unilateral secessionist steps

Qatar warned that the recognition set a dangerous precedent and undermined international law

Egypt coordinated diplomatic calls with Somalia, Turkiye and Djibouti, condemning the move

Sudan also issued a formal protestFor Gulf states, the Horn of Africa is not peripheral but a strategic backyard tied to Red Sea trade, food security investments, port access and maritime defence.

Israel’s entry into that equation, particularly amid broader Middle Eastern tensions, complicates an already crowded chessboard.

Ethiopia in the middle

Erdogan delivered his remarks while standing beside Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, a setting that mattered.

During the same briefing, Abiy renewed his long-running push for Red Sea access.

He called Ethiopia’s landlocked status a historical injustice, arguing that a nation of more than 130 million people cannot remain a “geographic prisoner”.

Securing peaceful, mutually beneficial access to the sea, he insisted, is not a luxury but a sovereign right and central to Ethiopia’s economic survival and the Horn’s future growth.

That ambition is what makes this so sensitive. In 2024, Abiy’s government signed a controversial memorandum with Somaliland to secure potential Red Sea port access.

The move sent shockwaves through Somalia and triggered a full-blown diplomatic crisis, as Mogadishu accused Addis Ababa of undermining its sovereignty.

Regional actors scrambled to contain the fallout.

Since then, Ethiopia has been walking a tightrope. Landlocked and under economic pressure, it is desperate for reliable sea access.

At the same time, it cannot afford a prolonged rupture with Somalia or alienate partners who see territorial integrity as non-negotiable.

The Abiy government has tried to calm tensions, keep dialogue open with Mogadishu, preserve its Somaliland port ambitions and embrace Turkiye’s mediation efforts, all without closing any doors.

Israel’s recognition of Somaliland makes that balancing act even harder, says a former Ethiopian foreign ministry official who asked not to be named for security reasons.

The official also points to the pressure the Turkish president piles on Addis Ababa.

“Erdogan didn’t just criticise Israel’s recognition of Somaliland. He did it standing beside Prime Minister Abiy. That was a message, and it puts Ethiopia on the spot,” the official tells The Africa Report.

“Addis Ababa has been trying to play both sides, repairing ties with Somalia while keeping its Somaliland port option alive.

“When Turkiye publicly doubles down on Somalia’s territorial integrity, it squeezes that middle ground. Ethiopia will find it harder to stay ambiguous.”