Key Takeaways:

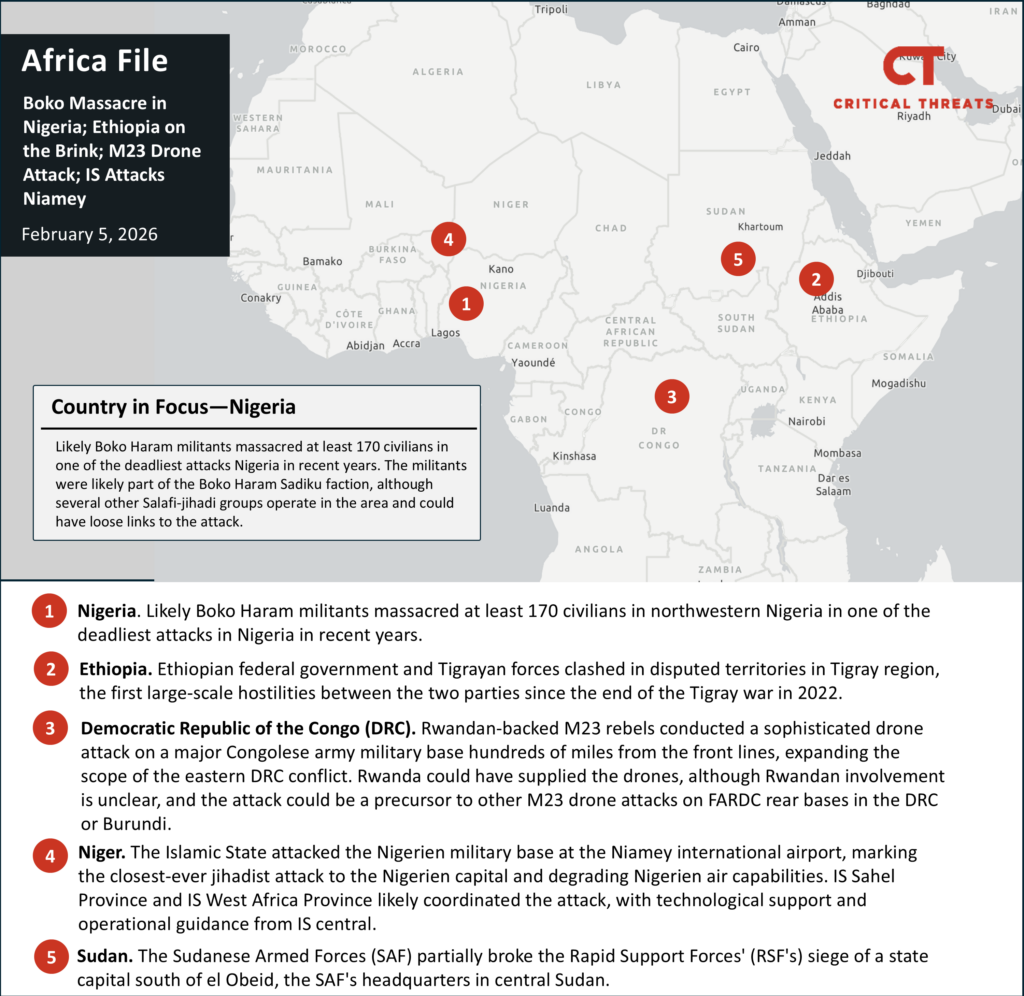

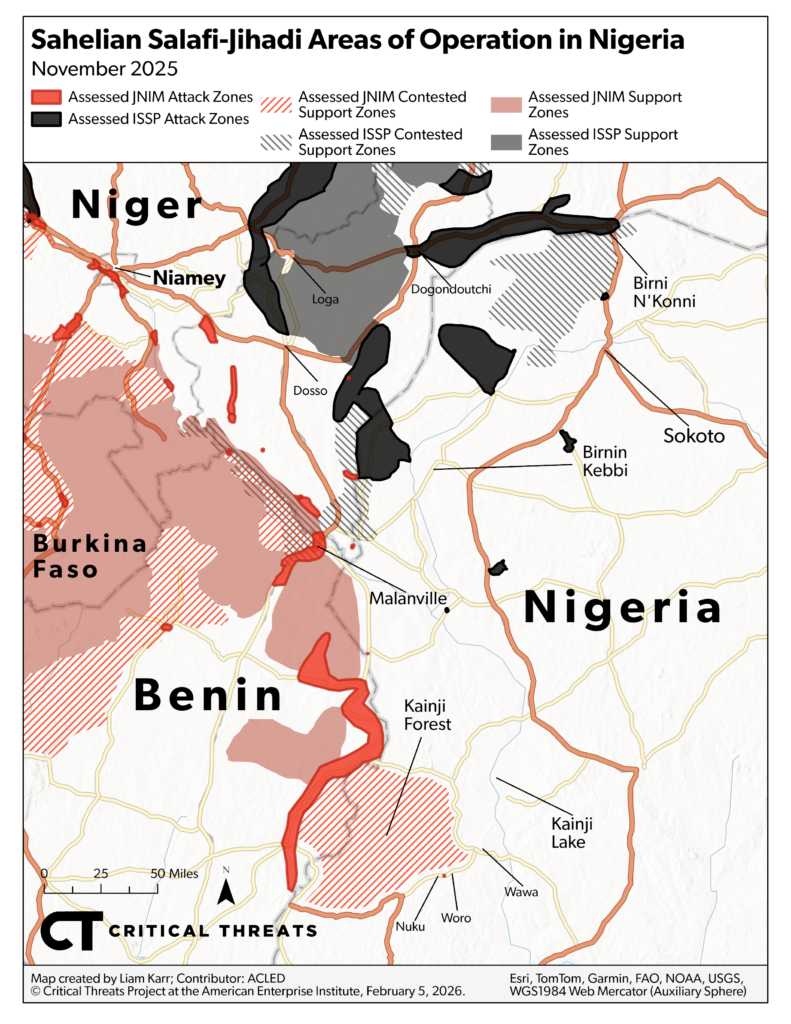

Nigeria. Likely Boko Haram militants massacred at least 170 civilians in northwestern Nigeria in one of the deadliest attacks in Nigeria in recent years. The militants were likely part of the Boko Haram Sadiku faction, although several other Salafi-jihadi groups operate in the area and could have loose links to the attack.

Ethiopia. Ethiopian federal government and Tigrayan forces clashed in disputed territories in Tigray region, the first large-scale hostilities between the two parties since the end of the Tigray war in 2022. The hostilities are unlikely to spark a war similar to the Tigray war in the immediate term, although outstanding issues related to the implementation of the peace agreement threaten to cause a broader conflict involving other countries in the region.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Rwandan-backed M23 rebels conducted a sophisticated drone attack on a major Congolese army (FARDC) military base hundreds of miles from the front lines, expanding the scope of the eastern DRC conflict. Rwanda could have supplied the drones, although Rwandan involvement is unclear, and the attack could be a precursor to other M23 drone attacks on FARDC rear bases in the DRC or Burundi.

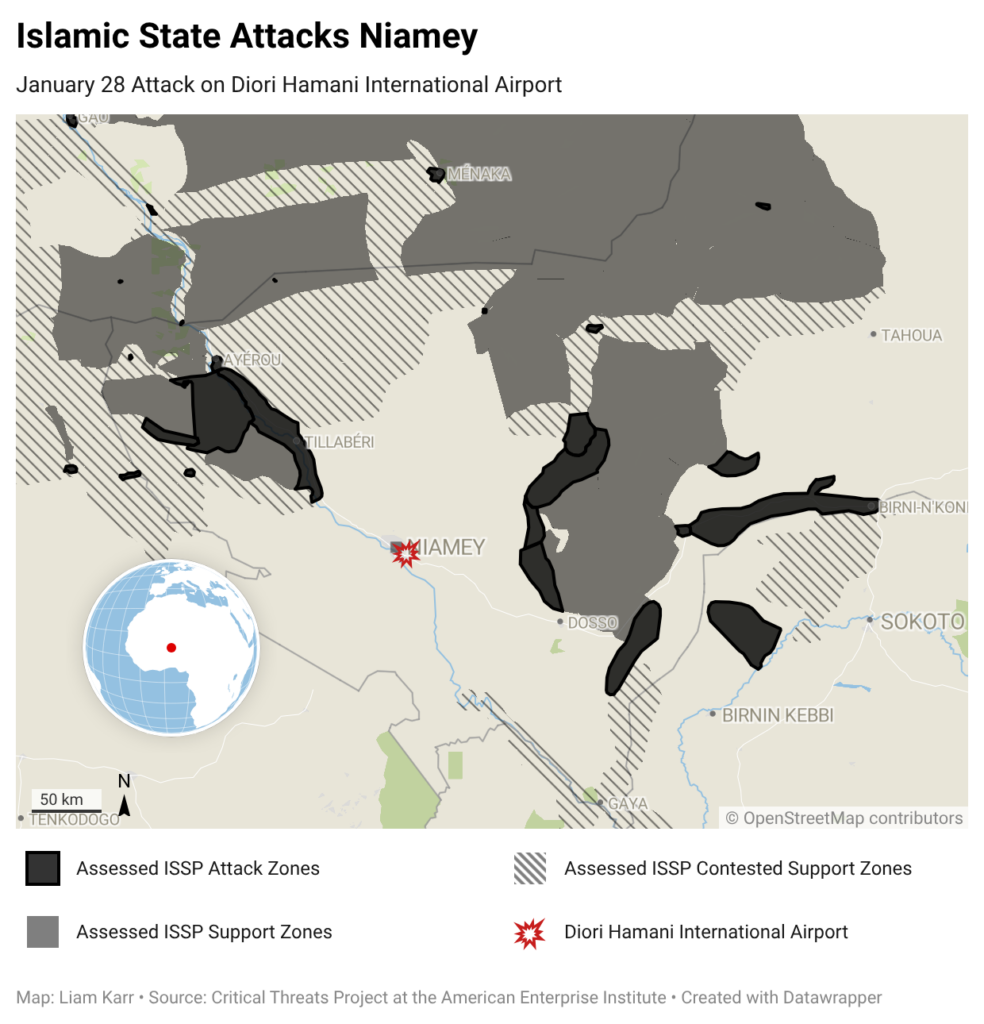

Niger. The Islamic State attacked the Nigerien military base at the Niamey international airport, marking the closest-ever jihadist attack to the Nigerien capital and degrading Nigerien air capabilities. IS Sahel Province and IS West Africa Province likely coordinated the attack, with technological support and operational guidance from IS central.

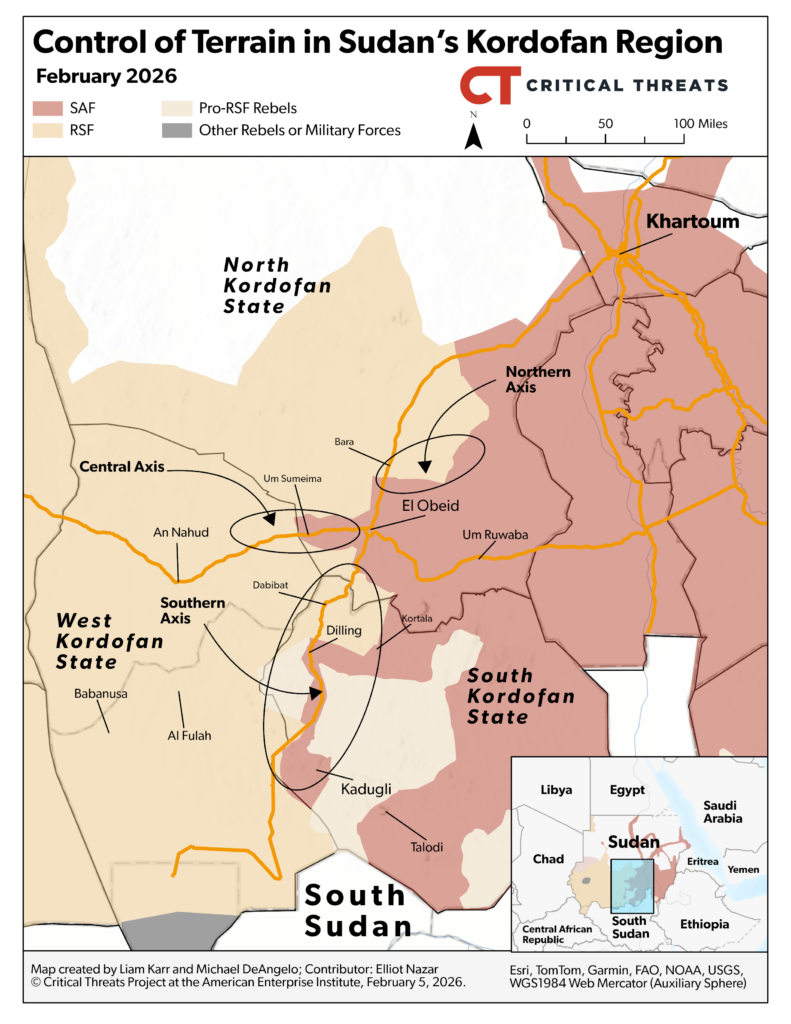

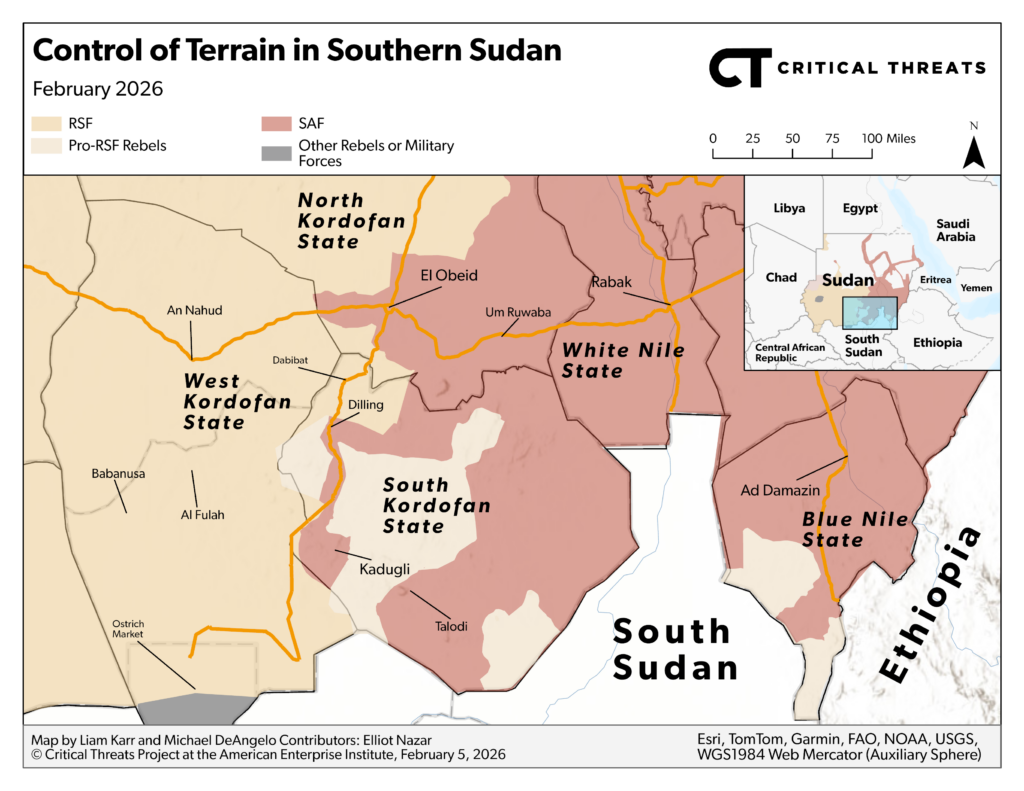

Sudan. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) partially broke the Rapid Support Forces’ (RSF’s) siege of a state capital south of el Obeid, the SAF’s headquarters in central Sudan. The SAF’s gains set conditions for it to break the RSF’s partial siege of el Obeid from the south and potentially give it another axis of advance toward the RSF’s center of gravity in western Sudan, although the RSF has opened a new front on the SAF’s flank in eastern Sudan that could divert SAF resources.

Figure 1. Africa File, February 5, 2026

Nigeria

Likely Boko Haram militants massacred at least 170 civilians in one of the deadliest attacks Nigeria in recent years. Militants attacked Nuku and Woro towns in Nigeria’s Kwara state on February 3.[1] The attack was particularly brutal, as attackers tied the hands and feet of several of their victims, slit some of their throats, and burned homes and shops in both towns over several hours.[2]

The attackers were Salafi-jihadi militants, who had moved into the area over the previous six months. Locals claimed that they recognized the gunmen as jihadists who had regularly preached in the area, encouraging locals to adhere to shari’a law and rebel against the Nigerian state.[3] The militants had also sent “warning” letters and pamphlets to the towns over past five months.[4] The final warning came in early January and was addressed from Jama’at Ahl al Sunna lil Da’wa wal Jihad, the formal name of Boko Haram, and its Lake Chad-based leader Bakura Doro.[5] Local leaders notified Nigerian security forces, which had withdrawn from the area after attacks in November 2025.[6] The militants opened fire during a sermon on February 3 after villagers rejected their appeals.[7] The attack is the deadliest jihadist-linked attack of the decade and the deadliest jihadist-linked attack ever outside of northeastern Nigeria.

The militants were likely part of the Boko Haram Sadiku faction, a Boko Haram group that has been active in northwestern Nigeria since 2020. Sadiku is reportedly the alias of a commander loyal to Boko Haram whom the late Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau dispatched to northwestern Niger in 2020.[8] Sadiku eventually established two bases on opposite sides of the border of Kaduna and Niger states, consisting of new recruits and members from Darul Salam, an Islamist sect active in northern Nigeria since the 1990s.[9] The Sadiku faction also had a complicated relationship with bandits, an array of various criminal gangs that operate across northern Nigeria in a warlord-like system. The group both attacked smaller bandit groups to cultivate local support in its core area, while collaborating with stronger warlords. This included Sadiku-bandit collaboration in the 2022 Abuja–Kaduna train attack, which netted the group thousands of dollars for its fighters, bandit allies, and civilians under its control.[10]

Elements of the Sadiku faction have relocated to the Kainji Lake National Park area, near the Niger–Kwara state border and site of the February 3 massacres, since July 2025.[11] The group’s relationship with its powerful bandit partners deteriorated in late 2024, forcing fighters in Niger state to begin to relocate. Large-scale civilian massacres are not the group’s typical modus operandi, but the Sadiku fighters in Niger state were relatively more hostile toward civilians than the faction’s other cell in Kaduna state. There had also been in an increase in attacks on civilians and looting raids on villages in the Niger-Kwara border area since Sadiku militants reportedly began entering the area, mirroring the tense relationship the faction’s fighters had with communities in Niger state.[12]

Figure 2. Sahelian Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in Nigeria

Several other jihadist factions also operate in northwestern Niger, including the Sahelian-based Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) and IS Sahel Province (ISSP), and could have links to the attack. Salafi-jihadi militants known as Mahmuda—named after their now-captured veteran jihadist leader Mallam Mahmuda—have been present in the Kainji Lake area since 2021, placing the attack within their area of operations. Mallam Mahmuda initially joined Boko Haram in the early 2010s, and researchers James Barnett and Umar Musa assess that he was likely part of the al Qaeda–linked Boko Haram splinter, Ansaru, given his travels to Libya, Niger, and Somalia throughout the 2010s.[13]

There is significant circumstantial evidence linking the Mahmuda faction to the entrance of al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, JNIM, to northwestern Nigeria since 2025. Nigerian security sources told Barnett and Musa that Mallam Mahmuda was directly in touch with JNIM factions in Burkina Faso, which have spread southward into Benin and along the Benin-Nigeria border in recent years.[14] Multiple researchers have noted that Francophone militants have crossed into the Kainji Lake area, Mahmuda’s base area, since 2021.[15] JNIM announced its presence in northwestern Nigeria in the second half of 2025 with a video claiming to show a small, Nigeria-based cell and two small-scale attacks in Kwara state, although it only formally claimed one of these.[16]

Mahmuda and JNIM are unlikely to be behind the attack. The February 3 massacres are not Mahmuda’s or JNIM’s typical modus operandi. JNIM and Mahmuda both put a greater emphasis on civilian outreach and nonviolence against Muslims than Boko Haram.[17] This outlook aligns with the approach taken by other al Qaeda–linked groups, whereas Boko Haram’s ultra-takfiri ideological beliefs frame any Muslim not actively joining the group as a legitimate target. Both JNIM and Mahmuda use coercive tactics against civilians—Mahmuda regularly abducts uncooperative local leaders, and JNIM enforces brutal blockades and accompanying kidnappings against uncooperative communities—but usually do not carry out massacres at the level of brutality or scale seen in the February 3 attacks.[18] JNIM has massacred hundreds of civilians in retaliation for cooperation with security forces in the Sahel, but the group’s cells in Nigeria are exponentially weaker than its subgroups in the Sahel, as the media it released in 2025 only ever showed a handful of fighters.[19]

Mahmuda and JNIM may be tolerating or cooperating with Sadiku militants in their area of operations around Kainji Lake given their vulnerable situations. Nigerian security forces arrested Mallam Mahmuda in mid-2025, which CTP assessed at the time could cause the group to fragment in the absence of his leadership.[20] It is possible that Mahmuda fighters defected to Sadiku, or at the very least are open to collaboration amid heightened counterterrorism pressure since mid-2025. Salafi-jihadist militants in northwestern Nigeria do not strongly adhere to their group affiliations due to their small size and the competitive environment with bandits, which also increases collaboration across groups based on human network connections.[21] Some Mahmuda militants reportedly fled to Benin, and given JNIM’s aforementioned small size, there may be fewer militants willing or able to contest the Sadiku militants moving into the area.[22]

A faction of ISSP-linked militants known as Lakurawa is unlikely to have carried out the attack, given that their area of operations is much further north in northwestern Nigeria near the Niger border. A Nigerian MP from the area accused Lakurawa of being behind the attack, although Lakurawa is locally used to refer to any militant from the neighboring Francophone countries.[23] References to ISSP’s Lakurawa faction specifically consists of ISSP-linked militants operating in Niger and across the Nigerian border in northern Nigeria’s Kebbi and Sokoto states. The February 3 massacres were over 150 miles south of the southernmost activity linked to ISSP’s Lakurawa.[24] The faction also functions as a key logistic node between ISSP and IS West Africa Province in northeastern Nigeria, decreasing its incentives to carry out a high-publicity attack that could draw further unwanted counterterrorism pressure after the United States conducted strikes against the group in December 2025.[25]

Ethiopia

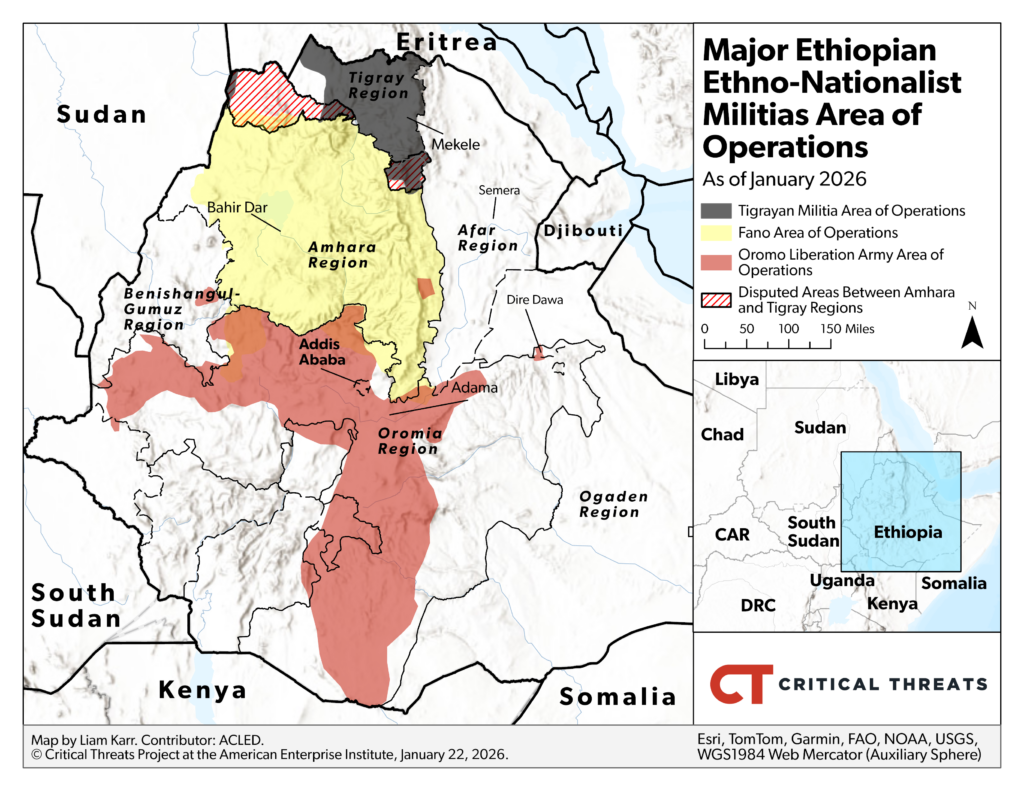

Ethiopian federal government and Tigrayan forces clashed in disputed territories in southern and northwestern Tigray region, the first large-scale hostilities between the two parties since the end of the Tigray war in 2022. The Tigray Defense Forces (TDF)—the Tigray People’s Liberation Front’s (TPLF’s) military force—launched an offensive to uproot Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) and Amhara ethno-nationalist forces from Tselemti district in northwestern Tigray on January 26.[26] The Amhara ethno-nationalist media outlet Amhara War Updates reported that the TDF used heavy artillery and mechanized units in the offensive.[27] The TDF overran ENDF positions across Tselemti, which borders Amhara region to the south, with open-source mapper Ethiopia Map stating that the TDF captured much of the district.[28] The ENDF and Amhara militias reportedly mobilized forces from Tselemti and surrounding zones in preparation for further TDF operations.[29] The TDF conducted more assaults from January 28 to January 30, including on localities bordering Amhara region, although the ENDF and aligned forces regained some positions by January 31.[30] The ENDF conducted multiple drone strikes across Tigray targeting TDF units, including leadership.[31]

The TDF separately seized control of key border areas in southern Tigray without significant resistance after the ENDF withdrew on January 29.[32] The TDF seized the towns of Alamata and Korem in Alamata district, which is located approximately 115 miles south of Mekele, the Tigray regional capital.[33] The Amhara and Tigray regional administrations both have long-standing land claims in Alamata and Tselemti.[34] The TDF also clashed with the Tigray Peace Forces (TPF)—an anti-TPLF Tigrayan force based in Afar region near the Tigray border—near Alamata and in the Wajirat district of Tigray and the Megale district of Afar.[35] Amhara War Updates reported further clashes between the TDF and ENDF and TPF on February 2.[36] The TPLF has accused the federal government of supporting the TPF.[37]

Figure 3. Ethno-Nationalist Militias Area of Operation in Northern Ethiopia

Figure 4. TDF Offensives in Tigray

Disputes over the federal government’s plan to return displaced Tigrayans from the Tigray war caused the outbreak of violence, but the hostilities have been brewing amid sharply deteriorating relations between the federal government and TPLF since early 2025. The Pretoria peace agreement, which ended the Tigray war, calls for the federal government to be the only armed force in Tigray’s de jure boundaries, including long-disputed territories between Amhara and Tigray.[38] This provision entails the disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of Tigrayan forces and the withdrawal of Amhara militias and the Eritrean military, both of whom fought against Tigrayan forces.[39] The withdrawal applies to areas that Amhara forces captured within the disputed territories, such as Alamata and Tselmti.[40] The agreement also requires that the federal government facilitate the provision of humanitarian aid and return of displaced Tigrayans.[41]

Amhara and Eritrean forces are still present in Tigray, however, which has prevented Tigrayan refugees from returning and provided a pretext for the TDF to avoid disarming.[42] The TPLF blames the continued displacement of more than one million Tigrayans on the presence of Amhara forces in disputed areas of Tigray.[43] Tigray Interim Administration (TIA) head Tadesse Worede has also stated that Amhara forces have prevented the reintegration of formerly displaced Tigrayans in Tselemti and that the reintegration process must change throughout Tigray.[44] The TDF has substantially slowed its demobilization, explicitly citing the federal government’s shortcomings in securing Tigray to justify its preservation.[45] Worede said that the recent clashes in Tselemti were a direct result of the federal government’s “failure to find a lasting solution” to the continued displacement of Tigrayans and presence of Amhara forces or to collaborate with the TIA to solve the problemset.[46]

The Pretoria agreement had already functionally collapsed in March 2025, when hardline TPLF factions launched a de facto coup against the federal government-backed TIA.[47] These factions disagreed with Pretoria agreement and viewed the TIA as federal government-controlled.[48] The TPLF’s coup allowed it to reassert political control over the TIA. The federal government eventually responded politically by revoking the TPLF’s legal standing as a political party, which prevents the TPLF from assuming formal federal or regional authority.[49]

The federal government and TPLF took increasingly belligerent stances throughout the rest of 2025. The TPLF reinstated a central military command in June, which gives the TPLF formal control over the TDF.[50] The TDF conducted raids in Afar, whose regional government has close ties with the federal government, in November to degrade the TPF.[51] The ENDF responded with a drone strike on TDF positions.[52] The federal government then halted funding to Tigray in December, contributing to a limited TDF revolt against Tigray’s regional administration over unpaid salaries.[53] The TPLF has also accused the federal government of imposing a fuel blockade on Tigray.[54]

The federal government and Tigrayan forces are unlikely to engage in a war on the same scale as the Tigray war in the immediate term, although the deep-rooted issues between the two sides heighten the risk of prolonged conflict. The TPLF has sought to de-escalate since January 31. Worede stated on January 31 that the offensive’s aims were limited to politically resolving the issues of returning displaced Tigrayans and ensuring Tigray’s border integrity and that large-scale clashes “should not have happened.”[55] Worede also reaffirmed the TIA’s desire to fulfill the Pretoria agreement and avoid war.[56] The TDF withdrew from seized positions in Tselemti to highlight the TIA’s willingness to engage in dialogue, and there have not been notable clashes in Tselemti since.[57] The TPLF additionally sent a letter to the African Union responding positively to AU efforts to mediate further talks.[58] Ethiopian Airlines resumed flights to Mekele on February 3 after canceling them from January 29 to February 2.[59] Clashes have occurred in southern Tigray despite the de-escalation in northwestern Tigray, however.[60]

The lack of a political resolution to the disputes over the Pretoria agreement make future clashes likely in the upcoming months, however, heightening the risk of a broader, prolonged conflict. The continued presence of Amhara forces and the TPF on the Tigray border is a leading point of contention for the TPLF. The federal government and TPLF also took escalatory action in 2025 despite both declaring a willingness to engage in negotiations. The TPLF’s revoked legal status limits the scope of potential negotiations.

The heightened tensions could spark a broader conflict with Eritrea, which would risk becoming a regional conflict involving multiple Red Sea powers in a most dangerous scenario. Eritrea would almost certainly get drawn into any war in Tigray on the side of the TPLF. Eritrea viewed the Pretoria agreement as a betrayal of its interests, as it did not dismantle the TPLF and mandated withdrawal of Eritrean troops from Ethiopia without Eritrean approval.[61] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s focus on securing sea access via the Eritrean port of Assab since 2023 has worsened tensions. Ethiopian officials, including Abiy, have repeatedly declared that Ethiopia will realize its “historic right” to sea access at Assab and implicitly kept the use of force to gain access on the table.[62] Eritrea has accused Ethiopia of warmongering and launched a nationwide military mobilization in February 2025, massing forces on the Ethiopian border and sparking international concerns of an imminent war.[63]

Eritrea has responded to its deteriorating relations with Ethiopia by aligning with the TPLF despite them being longtime rivals, including during the Tigray war. Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki reportedly met with TPLF officials in January 2025, pledging to support the TPLF in case of a war with Ethiopia.[64] Western diplomatic sources also claimed in early 2025 that Eritrean and TPLF officials had held multiple meetings.[65] The Guardian reported that Eritrean intelligence may have helped the TPLF execute its de facto coup in March.[66] Eritrea and Tigray reopened a border crossing in June with TPLF head Debretsion Gebremichael in attendance, and Gebremichael has since declared the TPLF’s intention to strengthen ties with Eritrea.[67] Eritrean troops remain in Tigray, and the Belgium-based, human rights-focused Europe External Programme with Africa think tank reported that Eritrea has assisted the TDF’s offensives in northwestern and southern Tigray.[68]

A protracted conflict would likely extend the regional proxy war already involving Sudan into Ethiopia given heightened competition across the Red Sea. Egypt and Saudi Arabia have recently increased military and political efforts to support the Sudanese Armed Forces in Sudan’s civil war, while the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is the Rapid Support Forces’ indispensable backer, supplying drones, air defense systems, and other equipment.[69] Saudi military intervention to repel an offensive by Emirati-backed proxies in Yemen led to an Emirati withdrawal from Yemen in early January 2026, and Saudi political outreach contributed to Somalia’s decision to cancel bilateral agreements with the UAE in mid-January.[70]

Figure 5. Emerging Blocs in the Red Sea Arena

Egypt and the UAE would likely get pulled into an Eritrea-Ethiopia war as part of this regional competition. The UAE is a strategic Ethiopian partner, providing billions of dollars of economic investment and weapons systems ranging from drones to fighter jets, and would feel the need to back its key regional ally.[71] Egypt recently signed a deal to invest in Assab that allegedly included naval provisions for Egyptian warships and has a high-level security dialogue with Eritrea.[72] Egypt and Saudi Arabia would almost certainly view the war as an example of Ethiopian aggression and Emirati-backed instability, with Egypt likely taking a strong approach in line with its recent regional stance. Egypt would also view the war as a zero-sum affair for Red Sea influence, given that an Ethiopian annexation of Assab would add another pro-Emirati port to the Red Sea at Egypt’s expense. Saudi Arabia has strong ties with both Eritrea and Ethiopia, however, likely limiting its involvement in any broader conflict.[73]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

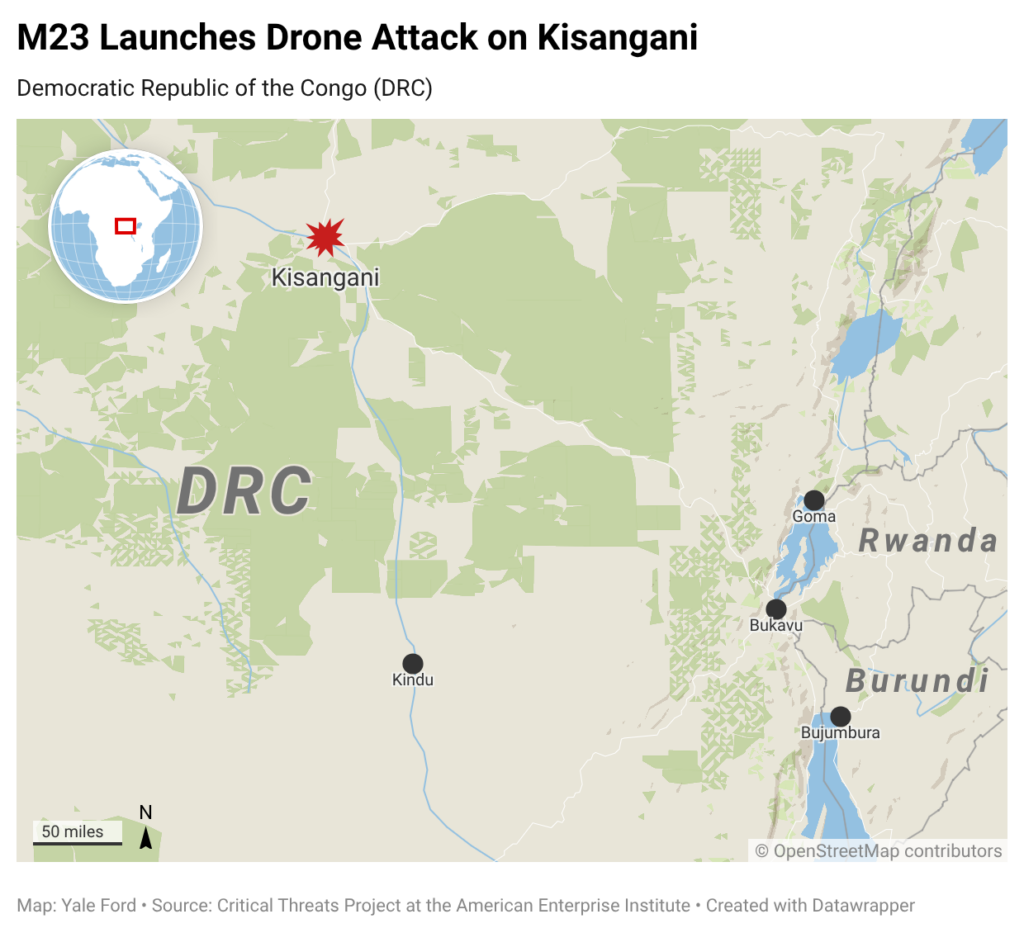

Rwandan-backed M23 rebels conducted a sophisticated drone attack on a major Congolese army (FARDC) military base, nearly 350 miles away from the frontlines in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The Tshopo provincial government claimed that the FARDC shot down eight one-way attack (OWA) drones operated by M23 near the Kisangani international airport in the central DRC between January 31 and February 1.[74] M23 reportedly used eight Turkish-made Yiha III drones in the attack, six of which the FARDC reportedly shot down and another that crashed near the airport without causing damage.[75] Yiha III drones are long-range, precision-strike loitering munitions designed to attack high-value stationary targets, including forward air bases.[76] Kisangani is the DRC’s fourth largest city, almost 350 miles away from the front line in North Kivu province in the eastern DRC and more than 250 miles northwest of Walikale town along the RN3. The attack marks M23’s first military engagement against the Congolese government west of the frontline since early 2025 and its most westward since the group reemerged in late 2021.

M23 claimed responsibility for the attack a few days later and framed it as evidence of the group’s expanded operational reach.[77] Corneille Nangaa, the head of M23’s political wing, claimed responsibility for the attack as a “warning” in a statement on social media on February 3.[78] M23’s political spokesman, Lawrence Kanyuka, claimed that the group destroyed the airport’s drone command center in a separate statement on February 3.[79] Nangaa said that M23 would begin preemptively targeting FARDC air bases and other military installations from which Congolese forces launch attacks against M23.[80]

Figure 6. M23 Launches Drone Attacks Against Kisangani

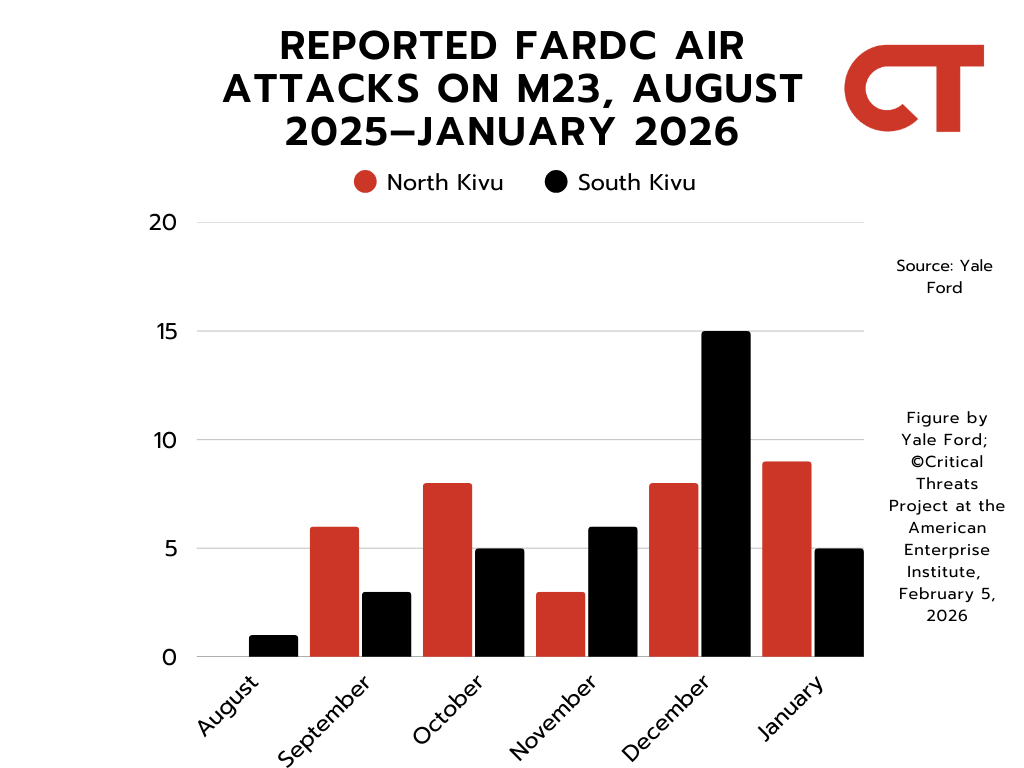

Kisangani has been an important rear base for the FARDC against M23 for several years. The airport, which is about 10 miles from city center, has been a major FARDC air and logistic hub, including for foreign military contractors employed by the Congolese government since mid-2025, according to the UN.[81] Kisangani houses a large part of the FARDC’s air arsenal of Russian-made fighter jets and medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) drones, specifically Chinese-made CH-4 Rainbow and Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 and TAI Anka drones.[82] These assets have been integral to an ongoing FARDC air interdiction campaign in North and South Kivu to deny M23 lines of advance to the DRC interior and degrade its supply lines in North and South Kivu.[83]

Figure 7. Reported FARDC Air Attacks on M23, August 2025–January 2026

It is unclear if Rwanda directly aided the attack, but it could have provided the drones, which would be a violation of its commitments under the Washington Accords and increase already-growing US pressure on Rwanda. Kanyuka implied that M23 carried out the attack without Rwandan military support using equipment that it captured in Goma in North Kivu and the Kavumu airport in South Kivu during its early 2025 offensive.[84] M23 captured up to 20 Belarusian-made long-range Berkut-BM loitering unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), likely OWA drones, according to the open-source intelligence outlet Janes, when it took control of Goma in January 2025.[85] The Berkut-BM drones are also long-range but are optimized mainly to strike time-sensitive targets before they can relocate.[86] CTP assessed in late 2025 that M23 has likely used the large amount of weaponry and military equipment that it seized from Goma in offensives.[87] The Kavumu airport in South Kivu had been the FARDC’s forward drone command center before M23 captured it in February 2025, but it reportedly only housed MALE drones—most of which went out of service in 2024—not OWA drones.[88] M23 had previously used small, short-range quadcopter suicide drones in attacks against the FARDC that were relatively ineffective.[89]

Rwanda is a close defense partner of Turkey and has deployed drones to support M23 offensives in the past. The Rwandan army (RDF) operates an undisclosed number of Turkish UAVs and signed a defense agreement with Turkey in November 2025 for the transfer of Turkish technology and to establish a drone assembly plant in Kigali, the Rwandan capital.[90] The UN has reported on the RDF’s deployment of armed drones to support M23 offensives on multiple occasions since early 2024.[91] M23’s offensive on Uvira in early 2025 involved the use of suicide and multi-role drones.[92] Rwanda violated its commitment under the Washington Accords to not “engage in, support, or condone any military incursions or other acts” in the eastern DRC by participating in the assault on Uvira.[93]

The United States has increased diplomatic pressure on Rwanda for its role in escalating the conflict and violating its peace commitments since December. Strong US political pressure on Rwanda and M23 led to the group’s withdrawal in mid-January. Senior US officials, including US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, have openly criticized Rwanda and warned of consequences to high-ranking Rwandan officials for violating the Washington Accords, including possible sanctions.[94] Rwanda and M23 acknowledged their ties publicly for the first time in late January, possibly hoping to further manage US diplomatic pressure.[95] The United States and the international community had specifically expressed concern about the increased use of attack and suicide drones during the Uvira offensive.[96] The French investigative outlet Africa Intelligence reported on February 5 that the Trump administration is expected to levy new sanctions on a several high-ranking RDF, Rwandan intelligence, and mining officials soon.[97]

M23 could similarly target Kindu in east-central DRC or Bujumbura in neighboring Burundi in a drone attack. Kindu is the administrative and commercial capital of Maniema province, located roughly 270 miles west of M23’s current position on the RP503 in Shabunda district in South Kivu. Kindu is an important FARDC command center that houses FARDC air assets and the FARDC’s 31st Rapid Intervention Brigade.[98] Kindu’s airport is the second most important FARDC airbase and staging ground behind Kisangani for the FARDC’s air and ground operations against M23 in the east. M23 has previously accused the Congolese government of using Kindu to deploy foreign mercenaries in the conflict and conduct drone strikes on its positions and civilians.

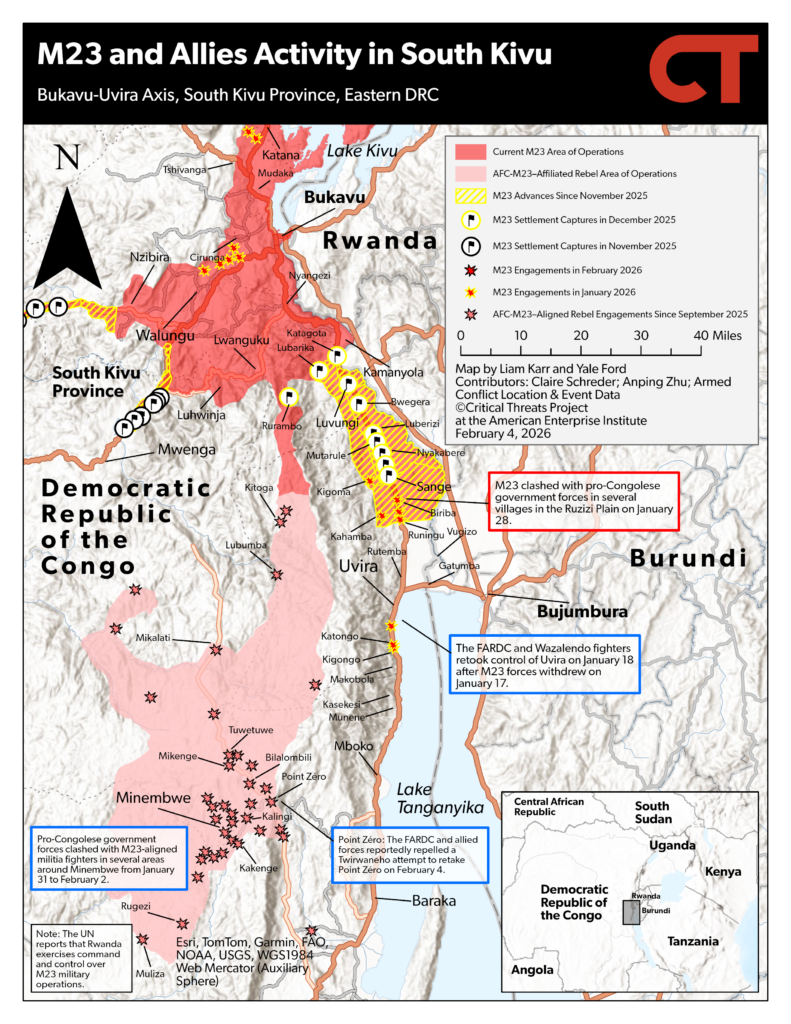

M23 could also target Bujumbura, although this would be a significant escalation and increase the risk of a regional war. The FARDC has used the Bujumbura airport, 16 miles to the east of Uvira in Burundi, to transfer weaponry and conduct frequent bombing runs on M23 and M23-aligned militia positions in South Kivu for months. Burundi is the FARDC’s most important and capable ally against M23 and M23-aligned rebel militias. The FARDC retook control of Uvira after M23 withdrew in mid-January and has conducted numerous significant airstrikes, some reportedly launched from Bujumbura, on M23 and M23-aligned militia positions in the highlands above Uvira since mid-December. CTP assessed previously that M23 is already setting political conditions to justify future offensive military maneuvers in South Kivu as the security situation returns to the status quo ante.[99] Nangaa said after the Kisangani attack that M23 had drawn a “red line” and would end the FARDC’s “air superiority” by targeting “every threat . . . at its point of origin.”[100]

Figure 8. M23 and Allies Activity in South Kivu

An attack on Burundi would risk a regional war and likely spoil deconfliction efforts between Rwanda and Burundi, however. Burundi and Rwanda are rivals in the eastern DRC, and both view their competition as potentially existential. M23 had halted their first southward advance along the Burundian border in South Kivu in early 2025 after Rwanda and Burundi deconflicted, which decreased the risk of a wider regional war between the two countries in the short term. Relations with Burundi slowly collapsed in 2025, however, and CTP assessed that M23 and Rwanda launched the Uvira offensive to knock the Burundian military out of the war, which heightened the risks of a regional war.[101] The Rwandan foreign minister told the French magazine Jeune Afrique on January 12 that Burundian and Rwandan security officials met on their shared border to deconflict twice in December after Uvira’s fall.[102]

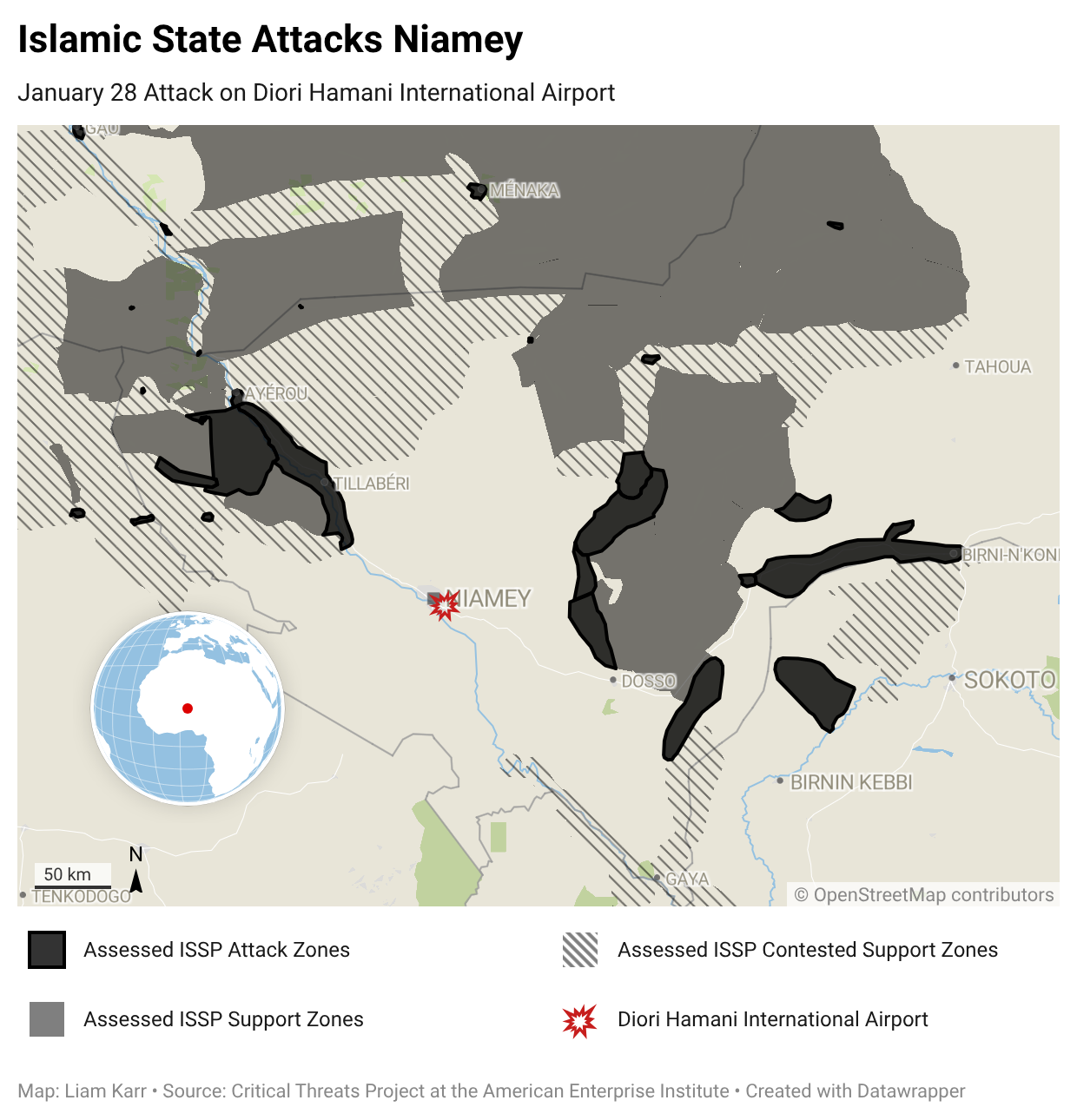

Niger

The Islamic State conducted a complex attack targeting the Niamey airport, weakening Nigerien counterinsurgency capabilities and marking the first major Salafi-jihadi attack in the vicinity of the Nigerien capital. The Islamic State conducted a complex attack on Air Base 101, at the Diori Hamani International airport, the night of January 28. The attack utilized one-way attack (OWA, or kamikaze) drones, mortar fire, vehicle borne improvised explosive devices, and heavily armed militants on motorcycles to target the air command headquarters and drone facilities.[103] The attackers burned several civilian and military aircraft, vehicles, and at least three hangars.[104] Local sources reported that the attack killed three Russian soldiers, 24 Nigerien soldiers, and wounded 18 others, while the Nigerien junta leader praised Nigerien and Russian forces for killing over 20 militants and detaining a dozen suspects.[105] The Islamic State claimed responsibility for the assault on January 30 and said that its fighters destroyed the air command center, several drones, aircraft, military vehicles, and ammunition stockpiles.[106] The airport is roughly five miles from the city of Niamey and six miles from the Nigerien Presidential Palace.[107]

The attack destroyed key Nigerien aircraft critical to intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance operations, and logistics. The Islamic State released footage of a burning aircraft and helicopter and later claimed to destroy six drones and seven military aircraft.[108] Open-source analysts identified the helicopter as an MI-171 SH model but are unsure whether the aircraft is a Diamond DA42 MPP Twin Star reconnaissance aircraft or a Hurkus-C combat aircraft.[109] Some analysts allege that the attack damaged both a DA42 reconnaissance aircraft and a Hurkus-C combat aircraft.[110] Reports of militants destroyed a Cessna 208 Caravan reconnaissance aircraft have also circulated heavy on social media.[111]

The damage could equate to the destruction of one-third of Niger’s ISR aircraft and its largest multi-role helicopter. Niger possesses four Cessna 208 Caravans and two Diamond DA42s for ISR.[112] Niger has three Hurkus-Cs, which combine ISR and attack capabilities and contain advanced technological features such as infrared and optical imaging.[113] The MI-171 SH combat-transport helicopter was Niger’s biggest multi-role helicopter, capable of carrying 36 troops and 4,000kg of cargo.[114] Niger’s remaining transport helicopters—two Bell 412HP Twin Hueys and five SA342 Gazelles—can accommodate roughly 14 and 5 people respectively.[115]

Figure 9. Islamic State Attacks Niamey

IS Sahel Province (ISSP) and northeastern Nigeria–based IS West Africa Province (ISWAP) likely coordinated the attack. The militants reportedly used kamikaze drones in tandem with the ground assault, which is a capability and tactic that ISWAP has previously demonstrated but ISSP has not.[116] ISWAP began experimenting with modifying commercially available quadcopters to drop grenades and as a OWA delivery vehicle for other improvised explosive devices since at least December 2024.[117] The group first used drones in combat on December 24, 2024, when it used four drones armed with grenades as OWA vehicles against a Nigerian military base in northeastern Nigeria.[118] ISWAP has since used armed drones in other attacks on Nigerian military installations throughout northeastern Nigeria’s Borno state[119] CTP could not verify additional reporting of ISWAP using drones as OWA vehicles beyond the December 2024 attack, but the group carried out a separate complex attack in northeastern Nigeria on January 29, 2025—less than 24 hours after the attack on the Niamey airport—in which it used a “drone bombardment” to cover retreating ground forces.[120]

Other elements of the attack further signal ISWAP involvement. Videos of the attack on the airport also show some attackers speaking languages more common in ISWAP’s area of operations than ISSP’s. IS media outlets released videos where militants are speaking Kanuri, a language spoken primarily in northeastern Nigeria. Another video shows attackers speaking Hausa, a language spoken primarily in northern Nigeria, and Arabic with a Nigerian accent.[121] The Islamic State’s Amaq channel claimed the attack rather than affiliated ISSP channels, which occurs most often when multiple provinces are involved.[122]

IS central enabled the attack with technology transfers to West Africa through its global network in recent years and encouraged or may have even ordered this kind of high-publicity attack. The UN reported in late 2024 that IS dispatched 13 trainers from the Middle East to the Lake Chad Basin to train ISWAP fighters on the acquisition, assembly, and deployment of combat drones.[123] IS is able to either move these trainers or pass on this guidance to ISSP through its General Directorate of Provinces, which disseminates guidance and resources and coordinates external activity across regional offices. ISWAP hosts the West Africa office, Maktab al Furqan, which oversees ISSP and ISWAP.[124]

IS has demonstrated the capability and intent to increase cooperation between ISSP and ISWAP in recent years. The late 2024 UN report claimed that IS explicitly directed ISWAP to increase support for ISSP to boost ISSP operations. This time frame loosely aligns with the strengthening of the ISSP-linked Lakurawa faction in northwestern Nigeria near the border with Niger. The group had been present in the area for years, but the UN and Armed Conflict Location & Event Data reported in 2024 that Lakurawa was increasingly functioning as a supply corridor and bridge between ISSP and ISWAP.[125] Lakurawa operationalized these support zones and began carrying out attacks in response to heightened counterinsurgency pressure in 2025 to retain its capabilities in the area.[126]

Sudan

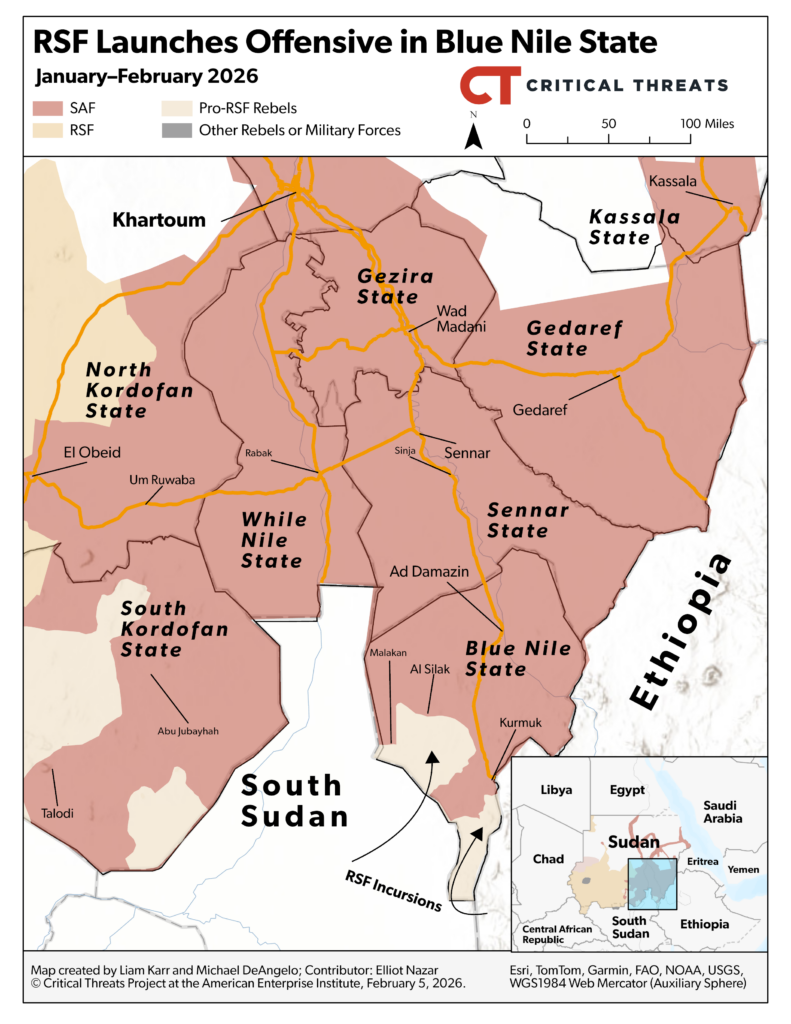

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) partially broke the siege of Kadugli, the South Kordofan state capital located 180 miles south of el Obeid, the SAF’s headquarters in central Sudan. The SAF reportedly conducted drone strikes on Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) al Hilu positions along the north–south road connecting Kadugli to Dilling—located 80 miles north—before launching ground assaults on February 1.[127] The SAF took several key positions along the road, including al Dashoul and Kega, which are located approximately 35 miles north of Kadugli.[128] The RSF and SPLM-N al Hilu had captured Kega on December 31, which enabled them to enforce a full siege of both Dilling and Kadugli.[129] The SAF then announced that it had cleared all RSF and SPLM-N al Hilu positions along the key road and lifted the siege on February 3.[130]

The SAF’s recent advances relieve pressure on partially besieged el Obeid and could open potential axes of advance toward RSF-controlled western Sudan or key oilfields in south-central Sudan. The SAF’s seizure of the Dilling-Kadugli road could enable the SAF to mass forces in Dilling to advance north toward el Obeid along the main north–south highway in Kordofan region. The RSF has established frontline positions near Kazgil, Bara, and um Sumeima, which are located approximately 30 miles south, 40 miles north, and 40 miles west of el Obeid, respectively. The RSF’s capture of Bara in late October cut a key water source for el Obeid.[131] The SAF tried advancing south from positions outside of el Obeid on December 31, but the RSF repelled the assault.[132] The SAF has already indirectly linked Dilling and el Obeid, however, after it partially broke the RSF’s siege of Dilling on January 26 via an alternate road to the east.[133]

Figure 10. Control of Terrain in Sudan’s Kordofan Region

The SAF could also use Dilling as a launchpad to flank RSF positions west of el Obeid on Sudan’s main east–west highway and eventually advance toward Darfur region, which is the RSF’s center of gravity. Dilling connects to an Nahud—the RSF-controlled west Kordofan state capital located 125 miles northwest of Dilling and 135 miles west of el Obeid—through a secondary highway and road. The SAF tried to advance along this route in May 2025, but the RSF repelled the advance and captured the key junction between the secondary highway and main north–south highway at al Dabibat.[134] The RSF-controlled crossroads town is located approximately 35 miles north of Dilling and 65 miles south of el Obeid. The SAF could alternatively prioritize recapturing the Heglig oilfields located 125 miles southwest of Kadugli, which the RSF captured on December 8.[135] The oil fields are an important source of fuel and revenue for the SAF, but the RSF’s capture has disrupted facility operations and forced the SAF to negotiate with the RSF regarding operations.[136]

Figure 11. Control of Terrain in Southern Sudan

The RSF and allied SPLM-N al Hilu have advanced as part of an offensive in southeastern Sudan from the Ethiopia and South Sudan border, however, which could draw SAF resources from central Sudan. SPLM-N al Hilu captured Deim Mansour, which is located 15 miles southwest of Kurmuk, on February 3.[137] Kurmuk is a key border town on the main highway linking western Ethiopia to southeastern Sudan.

Capturing Kurmuk would strengthen RSF supply lines from Ethiopia to Sudan. Ethiopia is likely facilitating UAE weapons shipments to the RSF through western Ethiopia, as Emirati-linked flights transporting suspected weapons have significantly increased since November 2025, and open-source analyst Rich Tedd tracked a shipment to an area near the Blue Nile border.[138] The SAF has also accused Ethiopia of facilitating weapons shipments and hosting RSF bases since December and mobilized forces in Blue Nile in January in anticipation of an RSF offensive.[139] An SAF official stated that SAF intelligence tracked SPLM-N al Hilu fighter movements from Ethiopia into Blue Nile prior to the recent attacks.[140] These attacks follow a series of assaults on SAF positions in Blue Nile on January 25 and 26 likely originating from RSF rear bases in South Sudan.[141]

Figure 12. RSF Launches Offensive in Blue Nile State