Africa’s complex security landscape was buffeted by the compounding effects of the growing regionalization of conflicts, militant Islamist group offensives, military coups, and external actor rivalries.

A look back at 2025 in graphics reveals an African security landscape being reshaped by growing external interventions, militaries emboldened to seize and consolidate power, and the proliferation of drones that expands the reach and lethality of armed combatants. The confluence of urbanization, demographic pressures, and the increasing regionalization of conflicts is further straining Africa’s already fragile security environment. Despite these challenges, numerous African countries have made noteworthy progress over the past year in building out their communications, road, rail, and space infrastructure to expand economic productivity and opportunities for the continent’s 1.5 billion, mostly youthful, citizens.

- Fragmentation in Sudan Strains Region

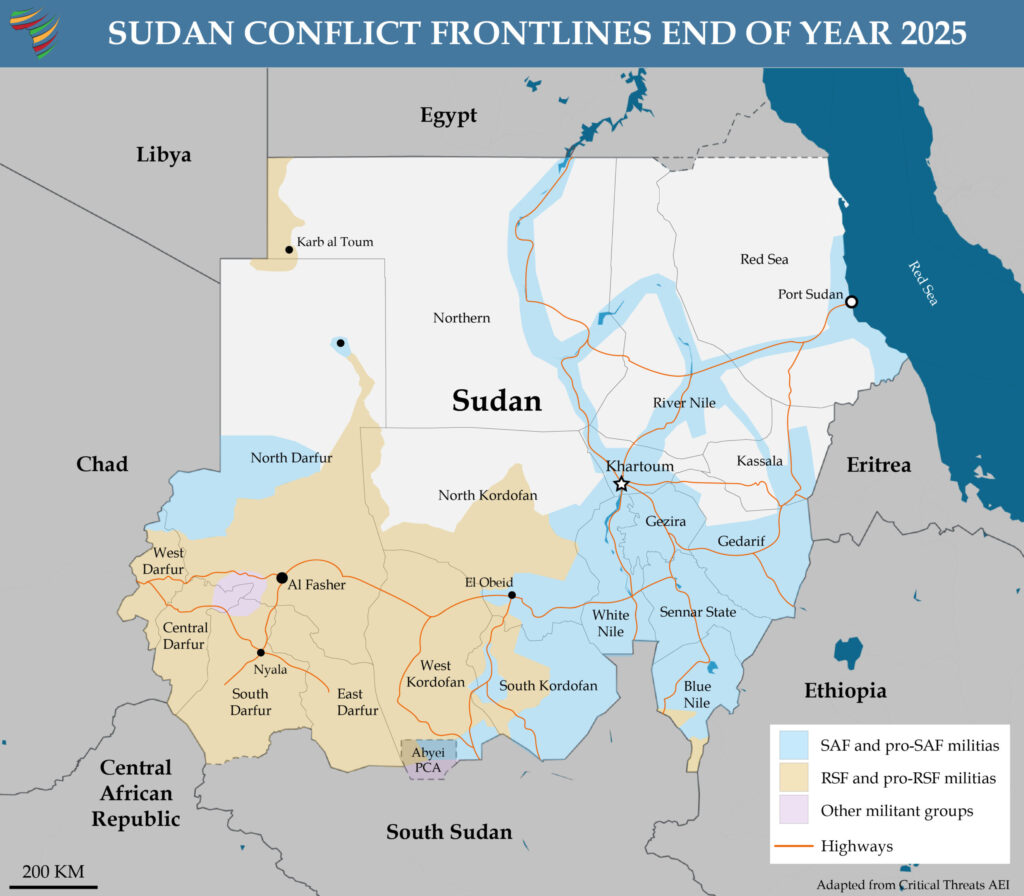

The conflict in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) commanded by General Abdel Fattah al Burhan and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) headed by General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo has triggered the fragmentation of Africa’s third-largest country and the creation of the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. Estimates are that 400,000 people may have already perished, and the country is now roughly divided into eastern and western areas of control.

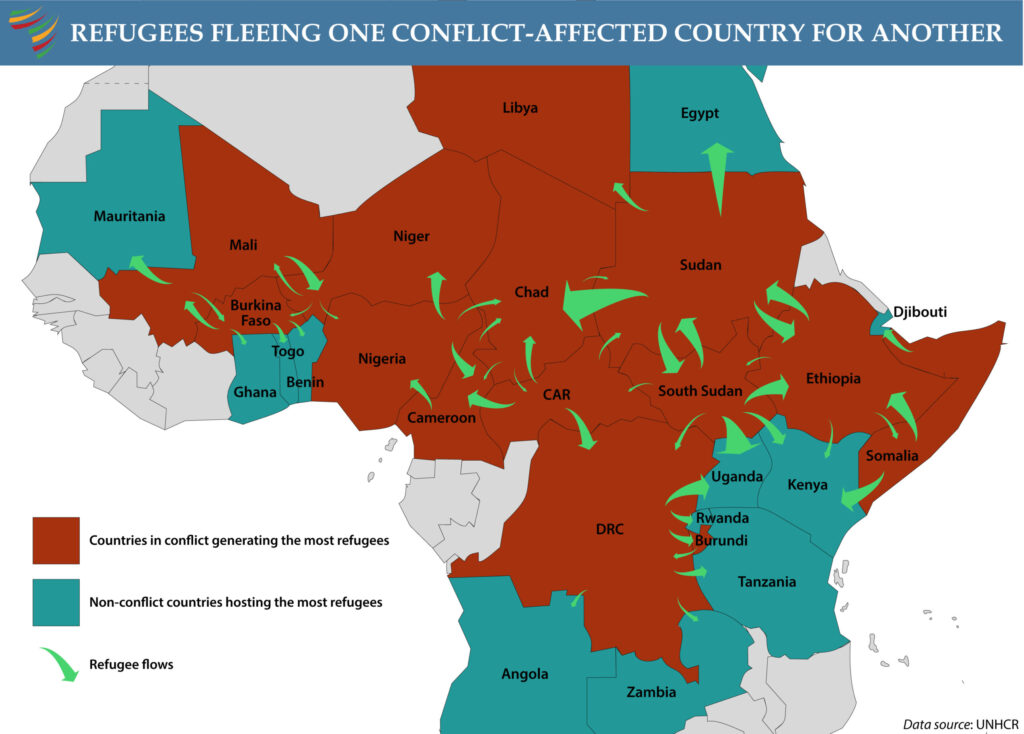

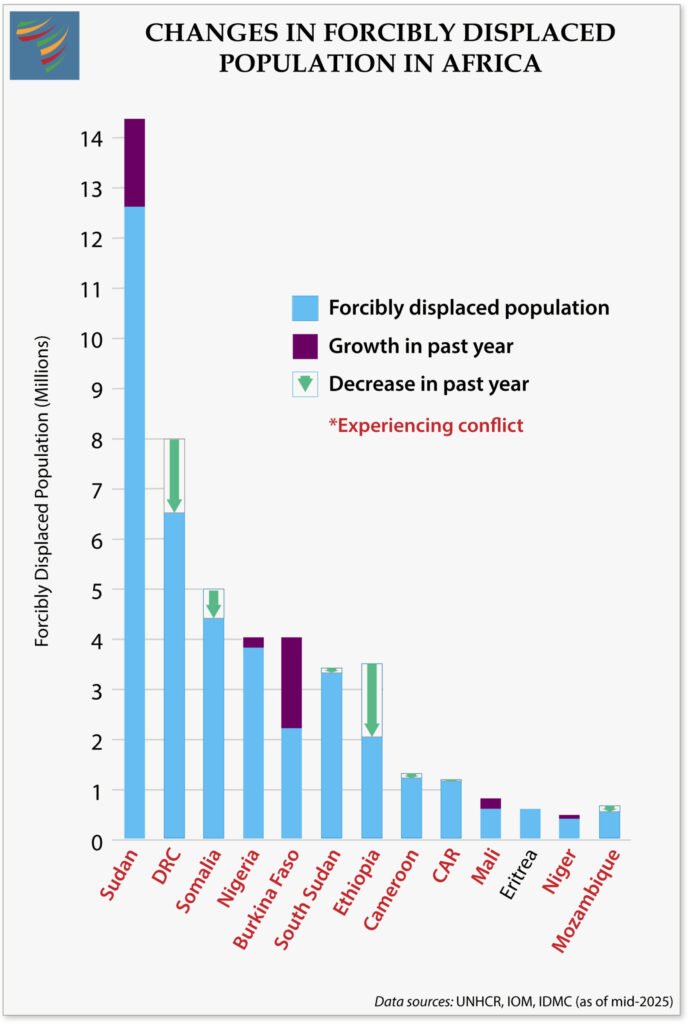

Sudan’s forcibly displaced population totals 12.8 million people. This underscores the brutality of the Sudan conflict, which continues to expand since erupting in April 2023.

In October 2025, the RSF captured El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur. The paramilitary group massacred thousands and forced tens of thousands to flee. More than 150,000 residents of El Fasher remain unaccounted for. With the collapse of the SAF’s last stronghold in the region, the RSF has been able to pivot its focus to Kordofan in the south.

More than 600,000 people are known to have been exposed to famine-like conditions in Sudan, with a concentration in Darfur. Due to the inaccessibility of this and other regions, the number of people facing famine could be far higher. The RSF has specifically targeted food production infrastructure, while both the RSF and SAF have targeted civilian markets and have prevented humanitarian assistance from reaching needy populations.

Regional actors have amplified the lethality, devastation, and persistence of this conflict through the provision of materiel, funding, and political support. The United Arab Emirates and Russia are considered the key sponsors of the RSF, while Saudi Arabia, Türkiye, Egypt, Russia, Qatar, and Iran have been backing the SAF.- Militant Islamist Groups Maintain Momentum

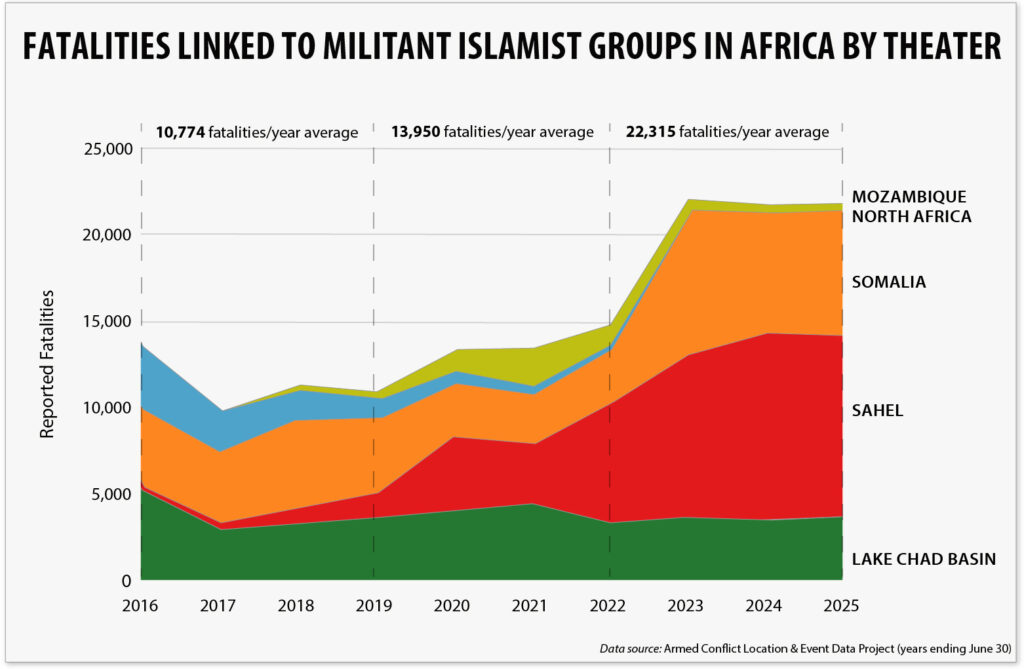

The 22,307 fatalities linked to militant Islamist groups in Africa over the past year sustain a record level of lethality observed since 2023 and represent a 60-percent increase from the 2020-2022 period.

The militant Islamist group threat is not monolithic but comprises some dozen distinct groups, each operating with their own unique leadership, organizational structure, objectives, fundraising, recruitment, and tactics.

The Sahel has held the designation of the most lethal theater of militant Islamist violence in Africa for 4 years in a row—accounting for 55 percent of all militant Islamist group-linked fatalities. An estimated 67 percent of all non-combatants killed by militant Islamist groups in Africa are in the Sahel.

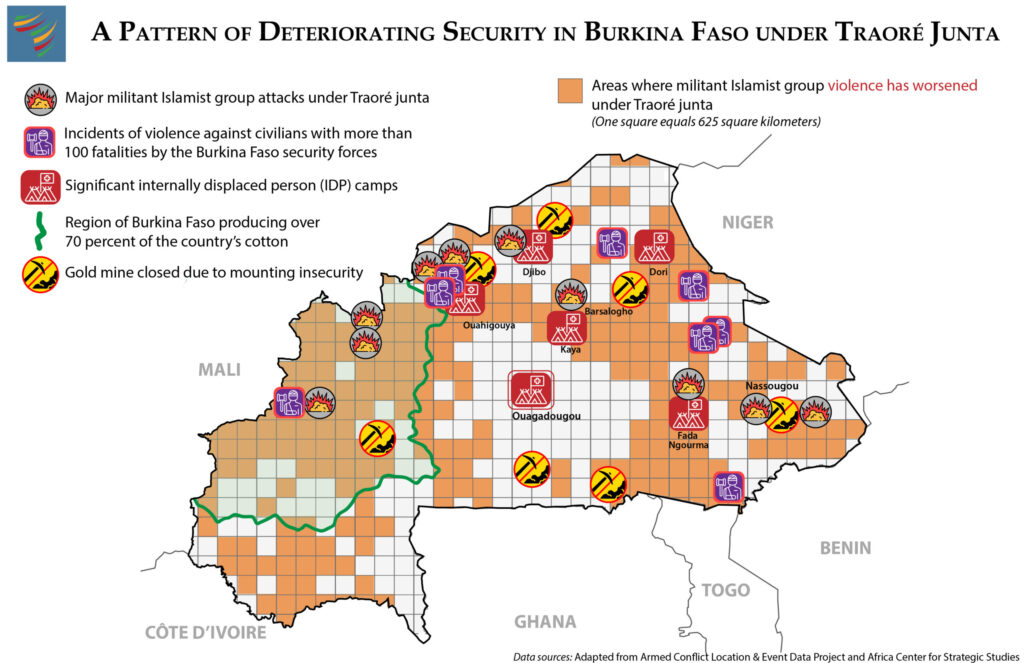

Security has deteriorated under each of the military juntas that seized power in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

Security has deteriorated under each of the military juntas that seized power in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

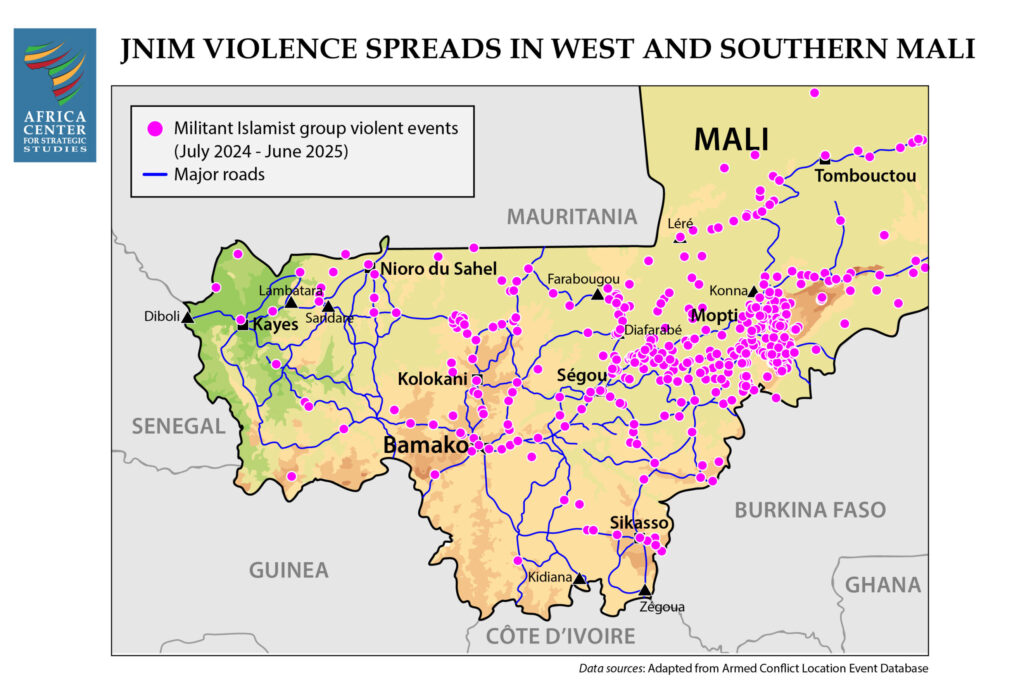

In Mali, blockades of key transportation arteries in the west and south have caused fuel and other shortages in Bamako, exposing the junta’s inability to provide security as well as its lack of legitimacy.

Fatalities linked to militant Islamist group violence in Burkina Faso have almost tripled in the past 3 years, reaching 17,775 deaths. This compares to 6,630 deaths in the 3-year period prior to the coup in September 2022. Estimates are that Burkinabe military forces now operate freely in as little as 30 percent of the country. Using siege tactics, militant Islamist groups have encircled roughly 130 Burkinabe towns and cities.

Since the October 2023 coup against the democratic government of President Mahmoud Bazoum in Niger, fatalities linked to militant Islamist violence have quadrupled (to 1,655 deaths). This includes a 49-percent increase in civilian deaths over the past year.

The expansion of militant Islamist violence in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has resulted in an increased number of attacks along and beyond the borders of coastal West African countries, from Mauritania to Nigeria.

Somalia

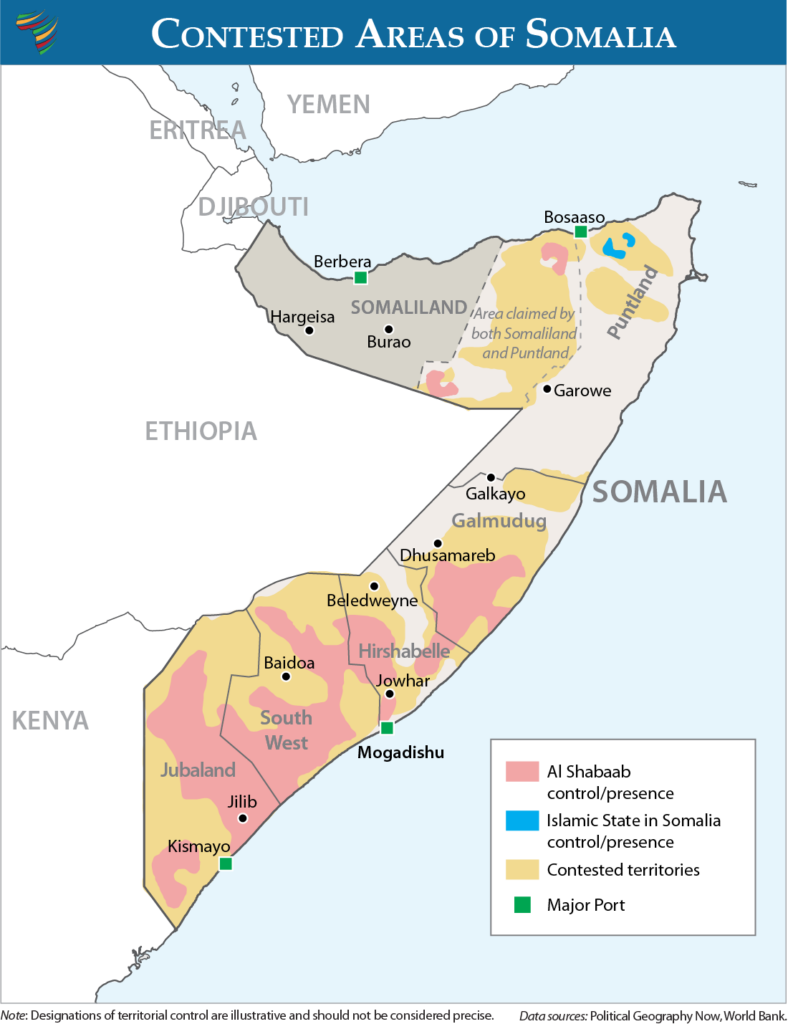

Somalia is the theater with the second-highest number of fatalities linked to militant Islamist violence, accounting for 28 percent of the continental total. The 6,224 fatalities linked to al Shabaab over the past year are double that of 2022.

A sweeping al Shabaab offensive across much of central Somalia in mid-2025 brought the militants to within 50 kilometers of Mogadishu

A sweeping al Shabaab offensive across much of central Somalia in mid-2025 brought the militants to within 50 kilometers of Mogadishu and renewed attention on the need to strengthen cooperation between the federal government and the federal member states, bolster the African Union peace support operation, and mitigate regional geopolitical competition.

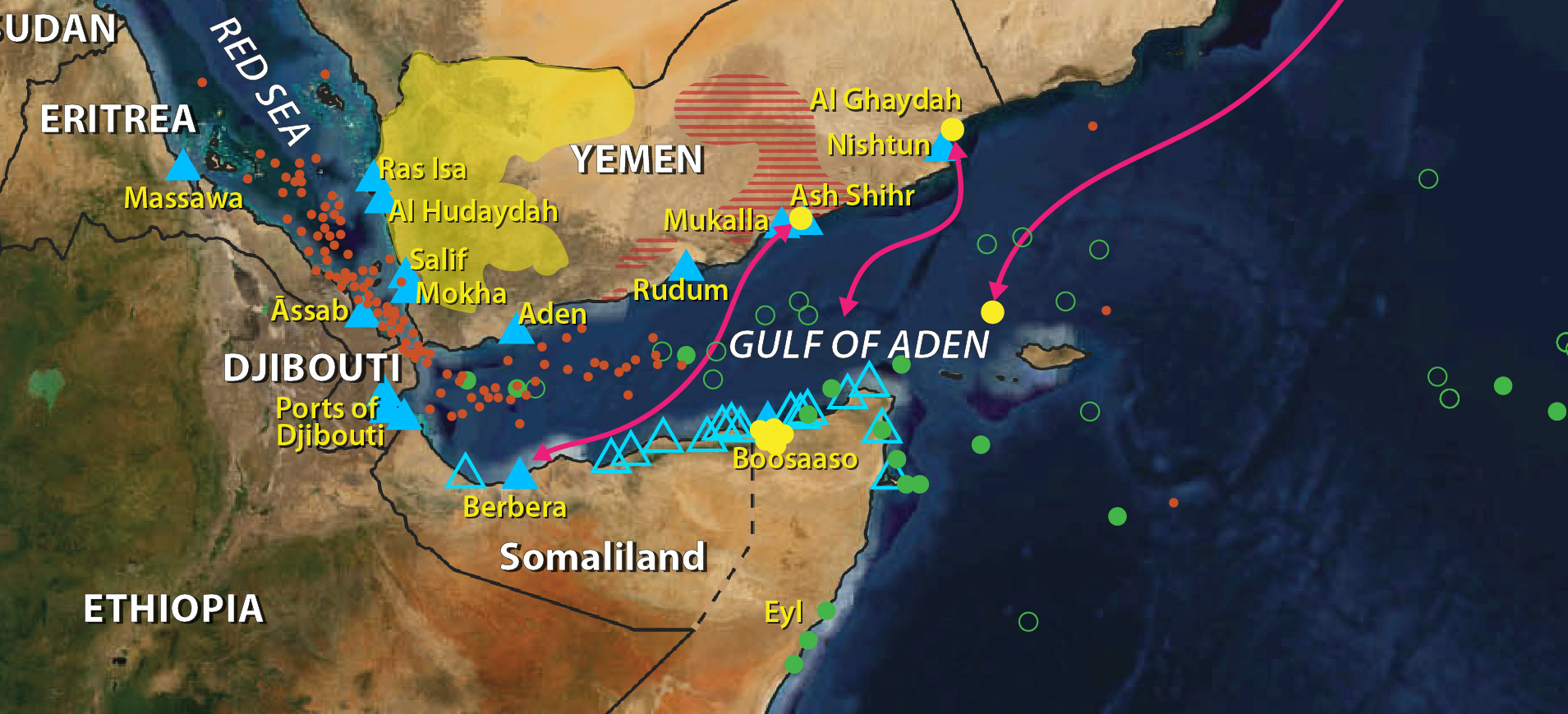

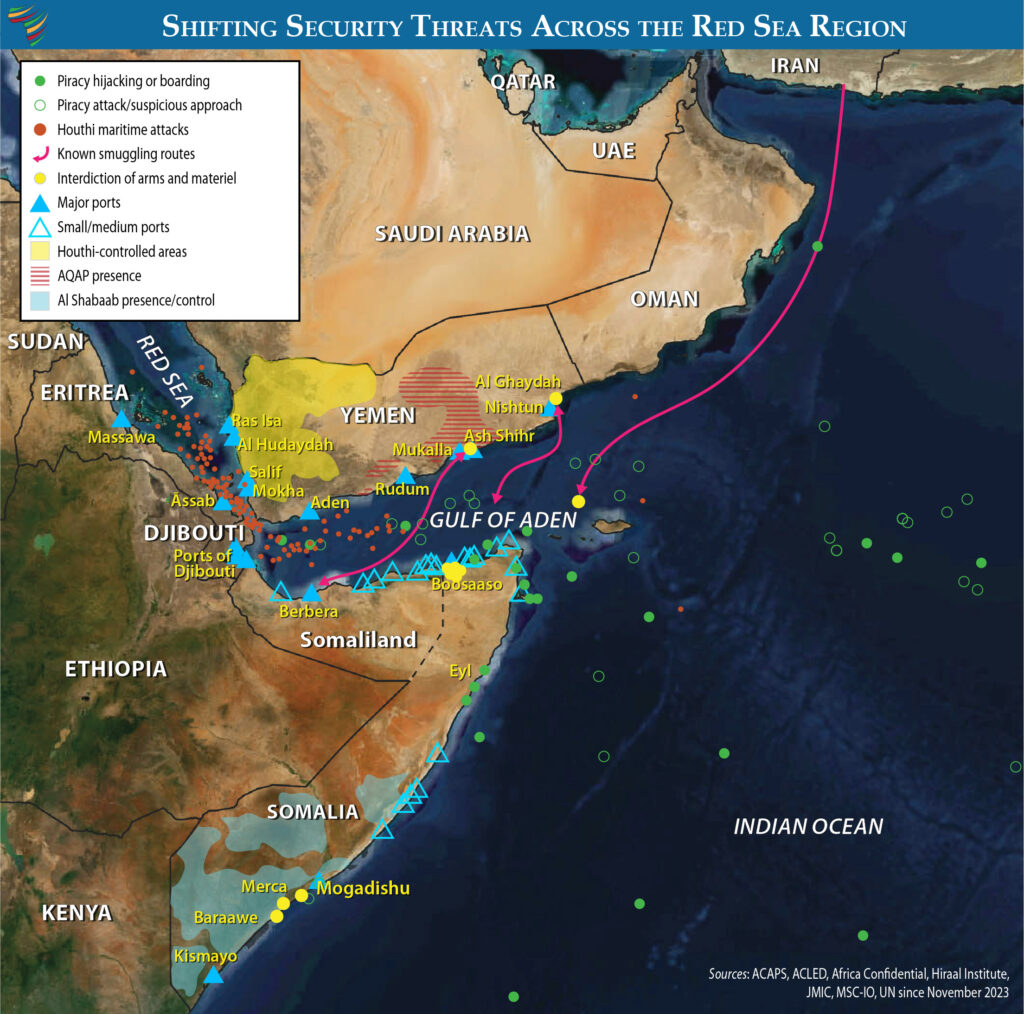

Estimates are that al Shabaab capabilities have expanded in the past year due to an increasingly cooperative relationship with Yemen’s Houthis. This cooperation has translated into improved materiel (including drones and ballistic missiles) and training for al Shabaab, which is believed to have directly contributed to their successful offensive operations in central and southern Somalia.

Somalia is also the base of the Islamic State in Somalia (ISS), located in the northeastern State of Puntland. While ISS has had operations in Somalia since 2015, it has gained increased scrutiny in the past year following United Nations and other reports that ISS had emerged as an administrative and financial hub for ISIS globally. These reports indicate that ISS had escalated its recruitment of foreign fighters (swelling its ranks from some 200 in 2018 to an estimated 1,000 in 2025).

Lake Chad Basin

The Lake Chad Basin saw a 7-percent increase in fatalities (3,982) linked to militant Islamist violence over the past year, demonstrating the continued resilience of Boko Haram and the Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA). The region accounts for 18 percent of total fatalities associated with militant Islamist groups on the continent.

Both Boko Haram and ISWA appear increasingly well-organized and equipped. Over the past year, ISWA overran 15 Nigerian military bases and, in a first, used night vision technology to launch attacks on these bases. It has also gained the operational expertise to deploy armed and surveillance drones, shifting the battlefield in the region. The two groups were linked to roughly equal numbers of fatalities.

Militant Islamist cells have also moved into northwestern Nigeria in recent years, which heretofore has been primarily the domain of organized criminal gangs (commonly referred to as “bandits”). Operating mainly in Sokoto and Kebbi States, the Lakurawa group has combined militant Islamist ideology with bandit-like kidnappings, extortion, and the seizure of assets. Comprising an estimated 200 fighters, Lakurawa is well-equipped with, among other tech, unmanned aerial vehicles for surveillance and satellite communications equipment.⇑ Back to Top ⇑

- Growing Impunity and Abuses of Power

Of the 10 elections scheduled in Africa for this year, only 3 were considered free and fair. Moreover, the election in one of the continent’s most stable countries, Tanzania, saw unprecedented levels of violence directed at supporters of the political opposition, ordinary citizens, and journalists. This continues a pattern of impunity by incumbents regarding the expectation to hold credible elections that provide a validation of popular support.

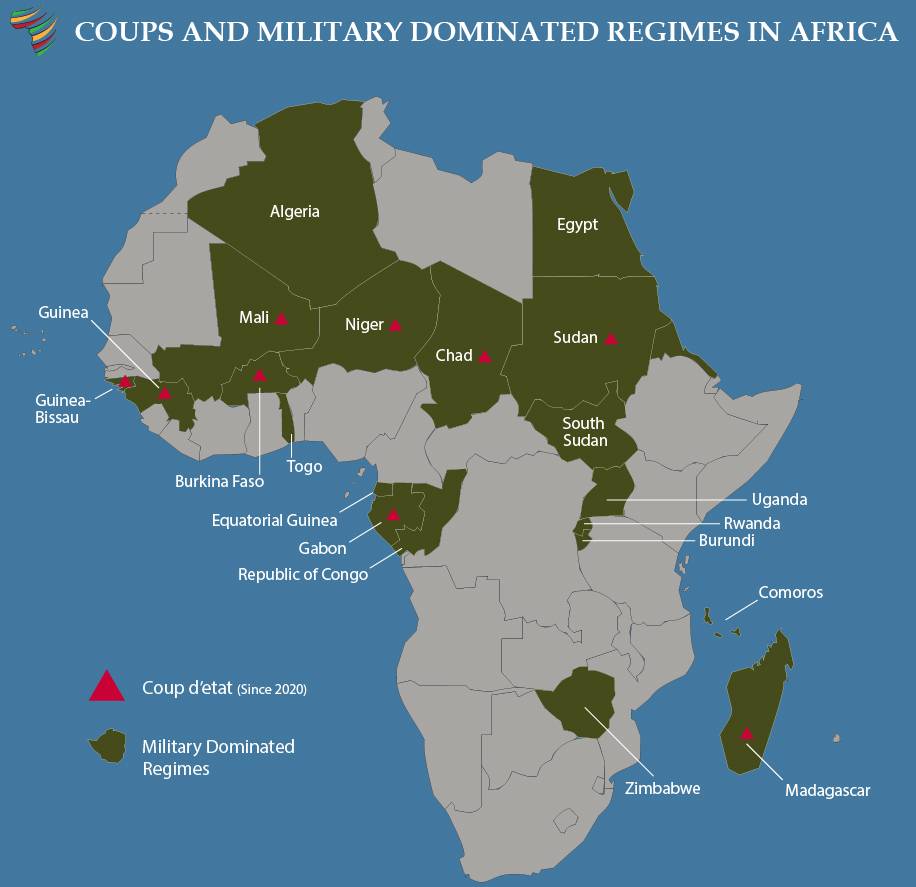

Military interference continued to be a dominant theme with military juntas attempting to consolidate earlier seizures of power through electoral exercises in Gabon and Guinea. A military coup in Guinea-Bissau in November preempted the long-delayed election there. Another coup, in Madagascar in October, further undermined constitutionalism in that Indian Ocean Island state. Benin was able to prevent a military coup in December with the help of ECOWAS forces from Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire. Suggestions that the Benin coup plotters may have been aided by the Sahelian juntas underscores their active effort to normalize military takeovers of democratic governments.

These coups add to the trend of recent years, resulting in nine African countries having had militaries seize power since 2020.

Rather than reformist, these coups have been accompanied by expanding repression. Political parties, independent media, and civil society groups have been repeatedly suspended, formally dissolved, or restricted from speaking to the public.

20 of Africa’s 54 national leaders have now come to power from coups or military actions—reprising the norm of military government many Africans thought they had long left behind. African leaders who took power via coup, in turn, are far more likely to evade term limits and perpetuate their time in power.

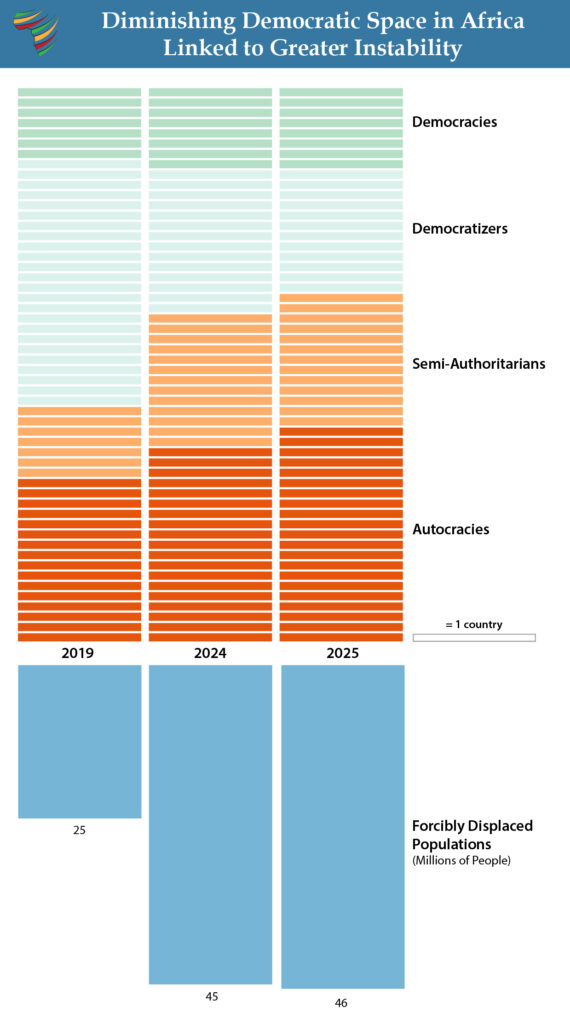

The growing number of military governments is part of a broader trend of democratic backsliding in Africa in recent years that is altering the contours of the continent’s governance landscape. Whereas there was a majority of democratic-leaning governments in 2019, this has reverted to a majority authoritarian-leaning today. Africa now has more authoritarian governments than at any time since 1998.

In addition to the direct political instability caused by democratic backsliding, exclusionary and unaccountable governance impacts security. Of the 15 countries facing major armed conflict, 13 are authoritarian-leaning.

Building on this pattern, 14 of the 15 African countries with the largest forced displacement populations have authoritarian-leaning governments, underscoring the regional spillover effects from unrepresentative governance.

Corruption is also more likely to thrive under the opacity of authoritarian government. The median ranking for Africa’s authoritarian governments on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index is 140 (out of 180 countries). This compares to a median ranking of 58 for Africa’s democracies. These differences in governance standards have direct implications for the upholding of the rule of law, protection of private property, investment potential, and job creation.⇑ Back to Top ⇑

- China and Russia Expand Foothold in Security and Critical Infrastructure Sectors

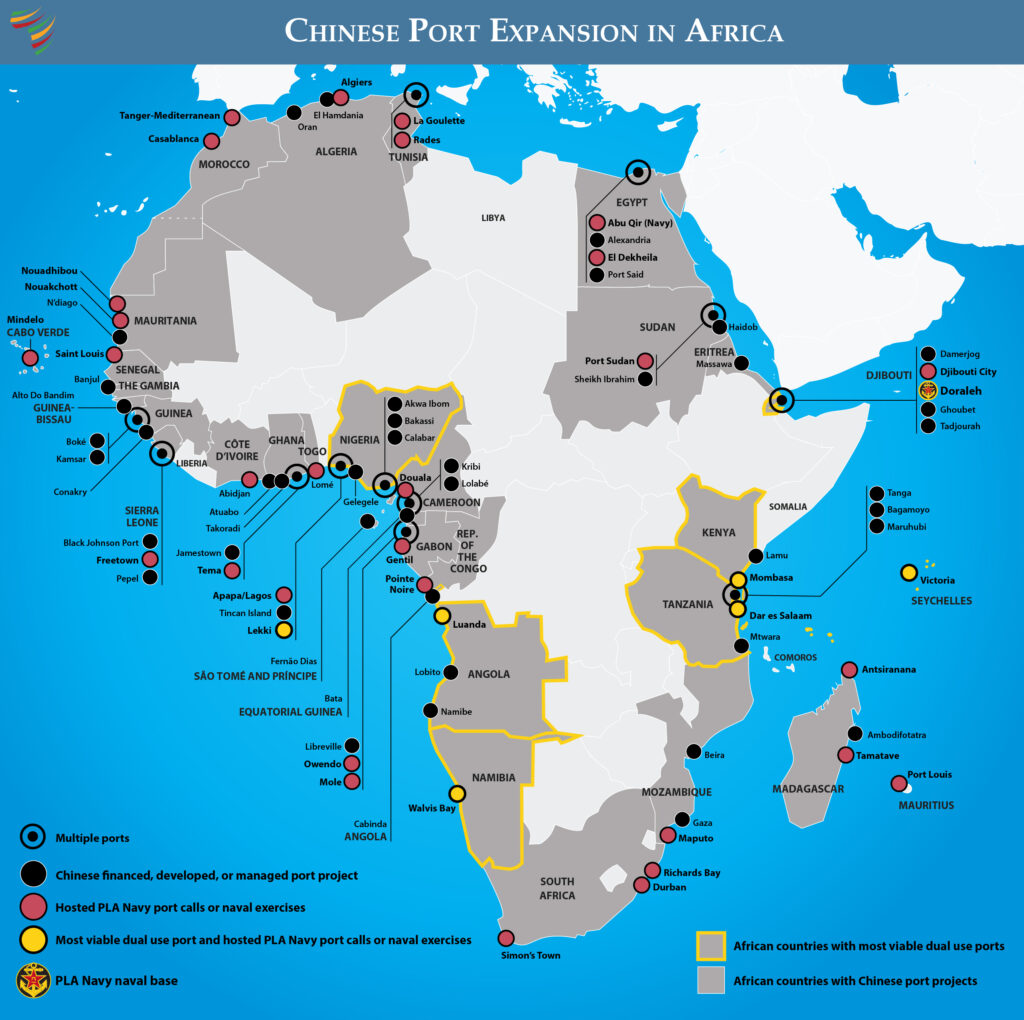

China is expanding its security engagements in Africa as part of its Global Security Initiative. These engagements include joint drills and operations with African forces, which have grown in scale and sophistication in recent years. The joint Chinese and Egyptian air force drills in May 2025 were the largest Chinese deployments of air power in Africa ever.

The joint Chinese and Egyptian air force drills in May 2025 were the largest Chinese deployments of air power in Africa ever.

The Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) Beijing Action Plan (2025-2027) is notable for containing more security commitments than any previous FOCAC action plans. Today, China is training roughly 2,000 African officers annually and has become a leading arms supplier on the continent. Roughly 70 percent of African countries now operate Chinese armored vehicles.

Chinese security engagements are often integrated with deepening political support for selected ruling parties and the promotion of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) security norms and governance practices.

Chinese state-owned firms are active stakeholders in an estimated 78 ports across 32 African countries as builders, financiers, or operators. Chinese firms are present in over a third of Africa’s maritime trade hubs—a significantly greater presence than anywhere else in the world. China’s expansive port development opens the door for China to repurpose commercial ports for military activities.

China has also gained a dominant position in Africa’s critical minerals sector. Of 166 Chinese-owned mining projects globally, 66 are in Africa, more than in any other region. This dominance often inhibits resource-rich African countries from advancing up the value chain.

With the fall of the Russian-supported Assad regime in Syria, Moscow has attempted to reposition its military assets in the Mediterranean to Libya (and closer to Europe). Flights from Syria to the al Khadim air base in eastern Libya controlled by militias loyal to General Khalifa Haftar have delivered troops, heavy weapons, armored vehicles, aircraft, helicopters, and surface-to-air systems.

Russia has also restored the Matan al Sarra Air Base in Libya near the borders with Chad and Sudan, enabling it to better support arms supplies to the RSF in Sudan.

Russia remains the leading external supporter of Africa’s military juntas whose extraconstitutional seizures of power have been a key entry point through which Russia has expanded its influence. Russia also maintains a strong presence in the Central African Republic, where Russian operatives are heavily involved in securing a third term for President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. This is consistent with a broader pattern of Russian efforts to undermine democracy in Africa as a means of strengthening Moscow’s influence on the continent.

Moscow has replaced its paramilitary Wagner Group forces on the continent with the Africa Corps, now officially recognized as a unit within the Russian Ministry of Defense. Yet, there are few differences in how these forces operate. Many Africa Corps soldiers are Wagner veterans, and the group has been accused of carrying on Wagner’s legacy of committing atrocities against civilians in Mali, Burkina Faso, and CAR.

Russia has ratcheted up its information warfare in the Sahel with its support of the military juntas and a highly coordinated information campaign to foster disillusionment and additional military coups in the coastal West African countries.⇑ Back to Top ⇑

- Growing Gulf Actor Competition in East Africa

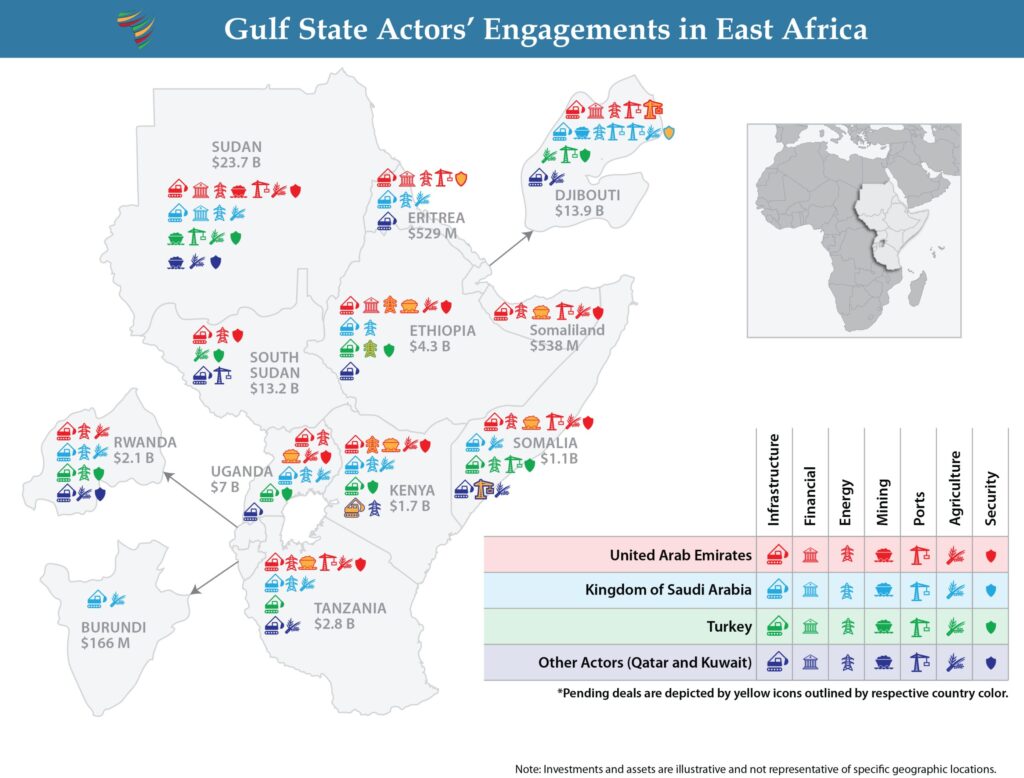

Gulf states (and Türkiye) have become increasingly intertwined with the economies, port operations, politics, and security forces of East Africa—with far-reaching implications for the region’s roughly 415 million citizens.

The UAE is by far the most engaged regional actor in East Africa, with an estimated $47 billion in projects.

Driven by economic interests, rivalries, and ambitions to be the dominant regional power, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye have become leading sources of capital, private sector engagement, and weapons flows into East Africa in recent years. Combined with heightened engagements from Qatar and Kuwait, this has amounted to roughly $75 billion in investments for East Africa in recent years.

The UAE is by far the most engaged regional actor in East Africa, with an estimated $47 billion in projects. This represents roughly 60 percent of all Gulf region capital inflows into East Africa and contributes to the UAE being the fourth-largest source of capital in Africa, following the European Union, China, and the United States.

As in Sudan, Somalia is becoming increasingly entangled in a regional conflict vortex that pits Egypt, Eritrea, Sudan, Qatar, and Türkiye against Ethiopia, Kenya, and the UAE.

Meanwhile, expanding capabilities and revenue flows have enabled a resilient al Shabaab to exploit power struggles within Somalia’s federal structure and pose a serious threat of taking Mogadishu. This, in turn, would open the door to Somalia becoming a hub for international terrorist groups.

The past year has revealed evidence of growing collaboration between al Shabaab in Somalia and Yemen’s Houthis.

The Houthis have used drones, missiles, and small boats to target over 100 commercial vessels attempting to traverse the 70-mile-long and 20-mile-wide (at its narrowest) Bab al Mandab Strait separating Africa from the Arabian Peninsula.

The rise in insecurity in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, and Western Indian Ocean has direct economic impacts on the global economy. Shipping through the Suez Canal (which accounts for about 12-15 percent of worldwide trade and 30 percent of container ship traffic) had dropped by 50-60 percent in the first half of the year.⇑ Back to Top ⇑

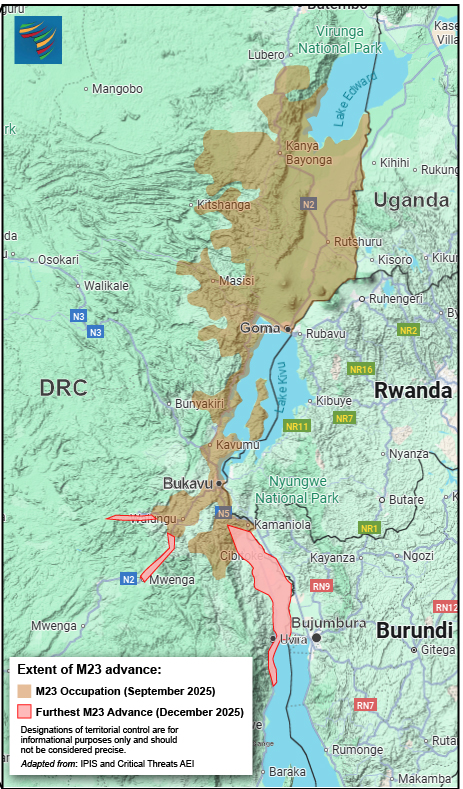

- Escalated Fighting in the DRC Risks Wider Regional Conflict The fall of Goma in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to the March 23 Movement (M23) rebels at the beginning of 2025 sent shock waves through the region and risks triggering a wider regional war. The Congo Wars of 1996-2003 precipitated the intervention of at least 8 African militaries in support of opposing sides and the deaths of an estimated 5.4 million Congolese.

It is widely recognized that M23 is backed by the Rwanda Defense Force (RDF) in support of Rwandan interests in the DRC. There is also evidence from UN investigations that M23 is receiving support from Uganda—underscoring the regional dimensions of the conflict.

In addition to Goma (population of 2 million), M23 has taken control of Bukavu, the capital of South Kivu (population 1.3 million), and in December pressed farther south to advance on the town of Uvira (population of 650,000). More than 2.5 million people have been displaced as a result of M23’s offensives. This includes 200,000 Congolese civilians who have been displaced due to the advances on Uvira.

Fighting in and around Uvira is another potential trigger for the expansion of the conflict. Uvira is just across the border with Bujumbura, and an estimated 10,000 Burundian troops have been in the DRC to protect Uvira. M23 reportedly captured hundreds of Burundian troops during the December offensive. Clashes in this region could easily escalate into a conflict between Burundi and Rwanda.

During the battle for Goma in January 2025, a firefight between the M23 and SADC mission in the DRC (SAMIDRC) forces, who were in the DRC to help contain the M23 threat, led to the deaths of 20 soldiers from South Africa, Malawi, and Tanzania—leading to SAMIDRC’s eventual withdrawal.

Mediation efforts by the United States and Qatar have generated multiple ceasefires over the course of the year. However, the multidimensionality of the DRC crisis makes it particularly challenging to resolve. In addition to the DRC’s territorial integrity and regional rivalries, other contentious issues include the:

Contested nationality and citizenship for Congolese of Rwandan and Burundian descent in eastern Congo

Control over Congo’s vast natural resources and mineral wealth

Weak legitimacy of the DRC government

Ineffectiveness and predatory behavior of the 150,000-strong Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC), which has been hobbled by indiscipline, parallel chains of command, erratic pay, and predatory behavior

Government deployment of mercenaries

The comprehensive Inter-Congolese Dialogue (ICD) and resultant Sun City (South Africa) Accords that ended the Second Congo War (1998-2003) may hold lessons for the current crisis, given the similar root causes, actors, and external dimensions.

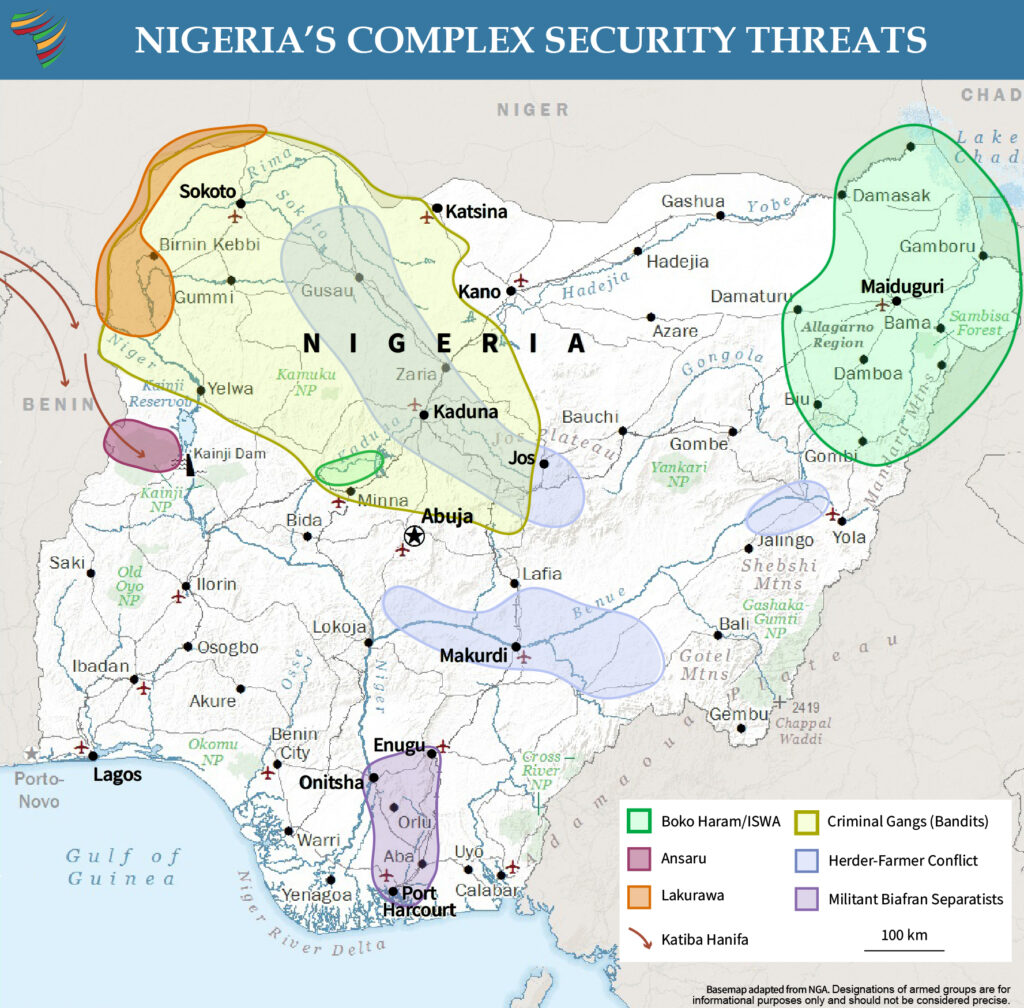

Regional Instability Exacerbating Strains in Nigeria

Nigeria faced an escalation of organized criminal attacks in its North West Region. Locally known as “bandits,” these criminal gangs have grown increasingly brazen—most prominently with their mass kidnappings of school children and others, who are then held for ransom as part of a lucrative revenue generation scheme.

Beyond the kidnappings, these criminal groups have been engaging in the targeting of key transportation routes, extortion, and the seizing of lucrative economic enterprises such as farms and mines. These criminal groups have thrived in the porous border areas with southwestern Niger, which has seen a dramatic escalation in insecurity following the military coup in 2023.

Nigeria is also facing cross-border attacks from militant Islamist groups (believed to be Katiba Hanifa from the JNIM coalition) entering from Benin. This represents a further ripple effect of the expansion of militant Islamist violence in the western Sahel, which has spread southward from Mali to Burkina Faso and is now threatening the coastal West African countries, including Benin and Nigeria.

The emergence of violent extremist groups in northwest Nigeria implies the long-feared convergence of militant Islamist groups with organized criminal networks.

The growing spillover threat across its western border is one of the reasons that Nigeria acted quickly to help stabilize the government of Benin following a coup attempt from a unit of disgruntled Beninois soldiers in December.

The emergence of violent extremist groups in northwest Nigeria implies the long-feared convergence of militant Islamist groups with organized criminal networks—infusing financial incentives with ideological zeal and terrorist violence.

Nigeria has simultaneously been staving off this convergence in the northeast, where Boko Haram and the Islamic State of West Africa have been active for the past 15 years.

The Nigerian government must navigate the expanding threat in the north while addressing a host of other ongoing security challenges, including farmer-herder violence in its Middle Belt that inflames Christian-Muslim tensions, a violent separatist movement in the south, riverine and coastal piracy, and cybercriminal groups that scam victims around the world.

Despite its challenges, Nigeria remains a major magnet for migration from across the West Africa region, one of the few African countries that have a net positive migration flow.⇑ Back to Top ⇑

- Evolving Technology Reshaping Warfare

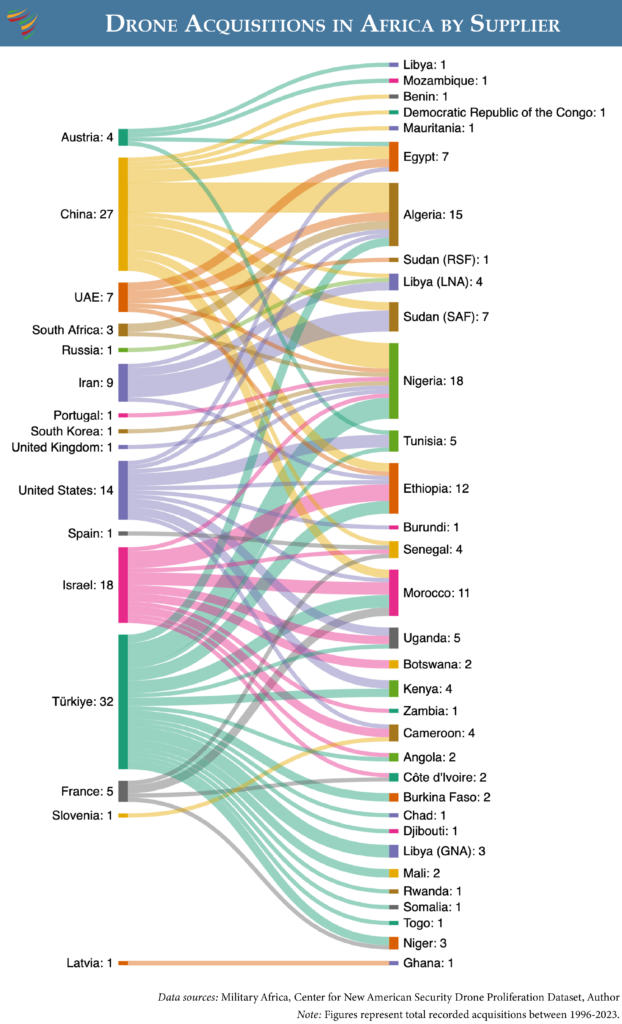

The proliferation of drones is reshaping the battlespace in Africa’s armed conflicts. With their decreasing costs, growing availability, and reduced need for operational expertise, drones are effectively providing the capabilities of a small air force and dramatically expanding the reach of armed combatants.

At least 31 African countries have acquired thousands of individual unmanned units, with the pace of government military drone acquisitions increasing.

93 percent of recorded drone strikes in Africa have been concentrated in six countries: Sudan, Ethiopia, Burkina Faso, Mali, Libya, and Somalia.

Armed nonstate actors in at least nine African countries—Burkina Faso, the DRC, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Somalia, and Sudan—have acquired and used military drones.

African countries are seeking to indigenize drone production capabilities, particularly with the proliferation of small, commercially made drones.

Middle powers, particularly Türkiye, are asymmetrically expanding their influence in Africa by meeting the continent’s rising demand for drones. Türkiye is Africa’s top supplier, with a total of 32 agreements. Israel, the UAE, and Iran have similarly expanded their reach on the continent via the supply of drones.

African countries are seeking to indigenize drone production capabilities, particularly with the proliferation of small, commercially made drones that are being modified and integrated into tactical operations. Enterprises in nine African countries (Algeria, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, and Tunisia) now produce military drones, supplying approximately 12 percent of Africa’s overall drone market.

The propagation of unmanned weapons systems has made urban areas increasingly vulnerable. Drone attacks by the warring parties in Sudan have resulted in mass civilian casualties in major cities across the country.

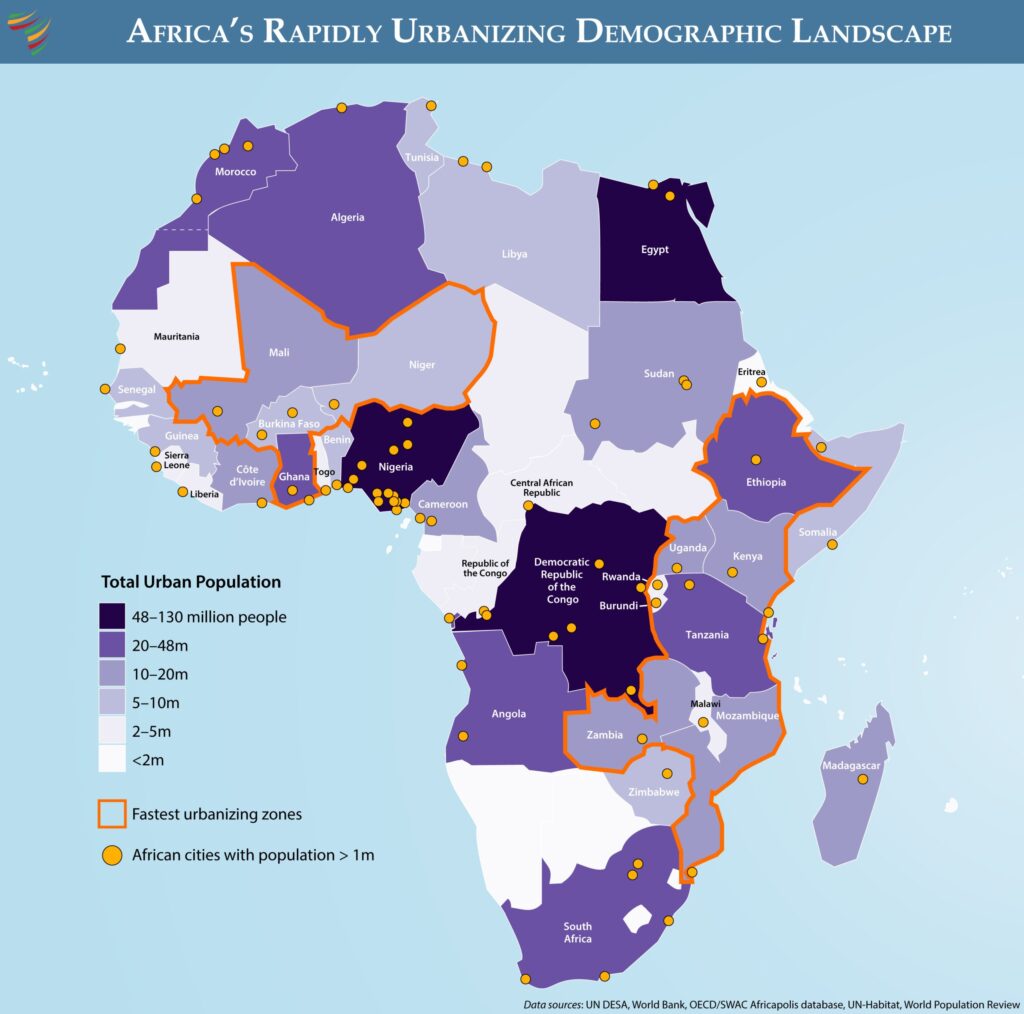

- Urbanization and Youth Protests Africa is the world’s fastest urbanizing region, with cities growing at an average rate of 3.5 percent per year (or 45 million people).

Nearly half of Africans—over 700 million people—already live in urban areas, a number projected to double to 1.4 billion by 2050. This pace of urban expansion is unprecedented in human history—and portends fundamental shifts in security requirements.

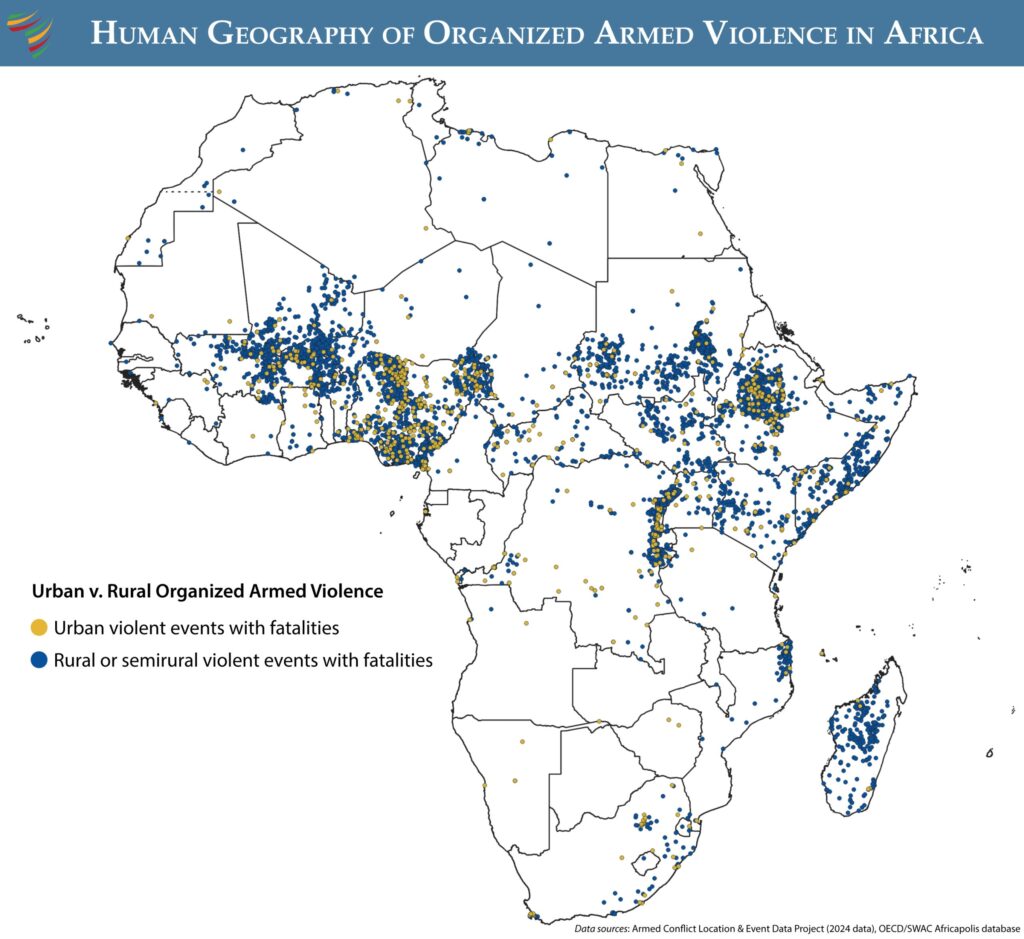

587 of 4,930 African cities suffered fatalities linked to organized armed violence in the past year. This figure has been rising in recent years, indicating that Africa’s urban areas are progressively becoming a target in the continent’s civil wars or entrenched insurgencies.

The conflict between the SAF and the RSF in Sudan, which has engulfed population-dense cities like Khartoum, Omdurman, and El Fasher, may be a precursor of this trend—and the resulting skyrocketing in noncombatant fatalities.

Similar patterns have been observed in the eastern DRC (around urban hubs like Goma, Bukavu, and Uvira), Somalia (in Mogadishu, Baidoa, and Kismayo), and Nigeria (Maiduguri). Growing incursions into urban peripheries and municipal centers by militant Islamist insurgencies in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger signal the possibility of increased civilian casualties in the Sahel, as well.

With urbanization, the world’s youngest continent has also seen numerous Gen Z protests in 2025 calling for greater accountability, job opportunities, and democracy. In Morocco, this was focused on national anger over systemic failures in the health care system, unemployment, and access to services.

Madagascar’s protests were hijacked by a military coup, underscoring the challenges of translating protests into accountable, democratic governments responsive to citizen interests.

In Madagascar, protests over water and electricity shortages led to questions over the legitimacy of the government and the fall of the sitting president, Andry Rajoelina. Rather than leading to reform, however, these protests were hijacked by a military coup, underscoring the challenges of translating protests into accountable, democratic governments responsive to citizen interests.

Youth were at the forefront of the protests around Tanzania’s October election, which was marked by significant irregularities according to regional and continental bodies. Tanzanian police and intelligence services subsequently fired live rounds into the crowds resulting in an estimated several thousand fatalities.

Gen Z protests have happened across a host of other African cities, reflective of frustrations where one million Africans enter the labor force every month but less than one in four find a job in the formal sector.

- Progress toward Agenda 2063 In line with Africa’s enormous potential as a youthful population, emerging market, and hub for technological and cultural innovation, the African Union’s Agenda 2063 has set out a vision and strategy to move toward an integrated, prosperous, democratic, and secure Africa. Noteworthy, if partial, progress was made in 2025 to translate this vision into practice.

With 54 members, the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is the largest free trade area in the world by membership. If fully implemented, it could boost intra-African trade by more than 50 percent and fundamentally reshape industrialization and regional value chains. Forty-eight countries have ratified the agreement, and the permanent secretariat in Accra, Ghana, is operational.

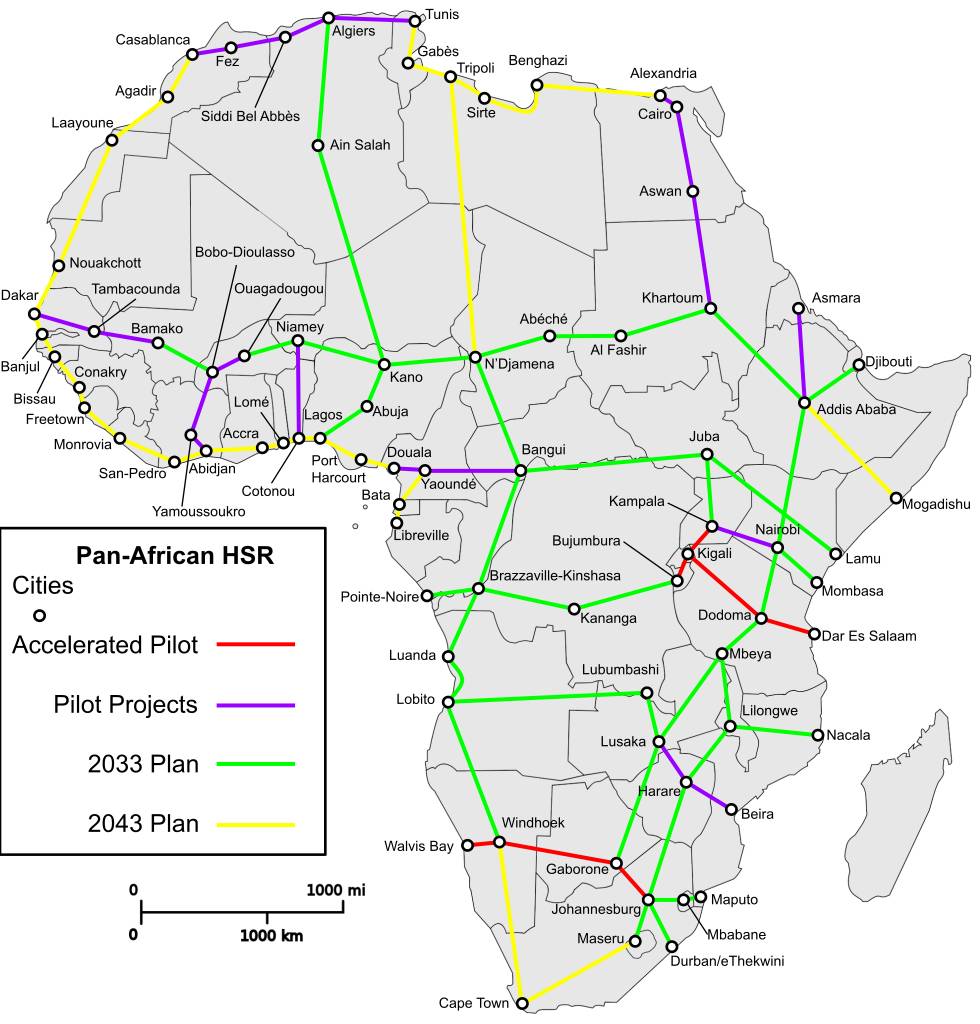

Creating infrastructure that facilitates intra- and interregional trade, commerce, and transportation is a central element of Agenda 2063. Infrastructure connectivity has advanced with new transport networks, broader electrification, and significant information and communications technology improvements. 16,000 kilometers of roads have been constructed out of the planned 54,000 kilometers under Agenda 2063’s Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa.

2 million kilometers of terrestrial fiber have been connected as part of the African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy to facilitate more reliable and accessible data, higher economic productivity, and e-services.

Infrastructure connectivity has advanced with new transport networks, broader electrification, and significant information and communications technology improvements.

The past year has seen progress in regulatory harmonization of the African Single Electricity Market (AfSEM). African Power Pools (for West, Southern, and East Africa) are aligning their strategies with some regions already interconnected and trading power.

2,000 kilometers of track comprising the Africa Union’s Integrated High-Speed Rail Network (HSR) have been constructed. The network will link North Africa to Southern Africa, with each region implementing a Regional Railway Master Plan fitting into the larger integrated plan. An additional 50,000 kilometers of track is envisioned by 2043.

Space is rapidly emerging as a strategic frontier for African countries, given its concrete contributions to improved communications, information access, economic development, and national security applications, including improved border surveillance, maritime monitoring, and tracking illicit trafficking.

The African Space Agency (AfSA) was inaugurated in Cairo in April 2025. AfSA provides a continental framework for aligning space programs, providing policy coordination, reducing duplication, and fostering shared access to infrastructure and data.

More than 21 African countries have established space programs, and 18 have launched at least one satellite. The continent has launched a combined total of 65 satellites (including miniature “CubeSats”), with over 120 additional satellites in development and expected to be launched by 2030.