This story documents live testimonies about the Iranian penetration in Sudan by Al-Hajj, Al-Liwa, Al-Dibalami and other sources that keep us from mentioning their names for their protection and for their safety, who agreed that this penetration in their country poses a threat to the territorial integrity of the Middle East and Africa in a way that cannot be ignored.

In the midst of the war in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, you can see the fear in the eyes of people and a sense of awe in their carefully selected words when dealing with strangers. I thought about this while waiting in the lobby of the hotel near the Blue Nile for the car that would take me to a meeting at the house of the only person I could trust to provide me with certain details about Iran’s security and military involvement in Sudan. I’ll refer to him as “pilgrim.”

And I’m waiting. I’ve reviewed my notes. Everything in Sudan attracts attention: a low standard of living, horrific poverty rates, business stopovers, high unemployment, and a frightening lack of public security. The country is clearly camped everywhere, even in the city’s wealthier neighborhoods. I can see it from the window of my hotel, surrounded by the greatness of the King Farouk Mosque, the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the Sudanese National Museum. This made me wonder about an important question: How was this country kidnapped from its previous state of peaceful coexistence among its neighbors?

Over the past ten years, as a Middle East researcher, I have closely followed Iran’s incursions into Africa and its successful efforts to establish links with military institutions in the targeted countries. You have noticed how Iran’s influence has expanded in the region and across the world by creating networks of “non-state actors” and armed militias that are sowing chaos and ensuring the failure of vital national projects under the banner of “resistance and resistance.”

Iran is planning its long-term strategy of carefully “exporting the revolution” at the political, military, economic, and security levels. This strategy began with the Iran-Iraq war and expanded across Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, leading to the conflict in Gaza and Africa. The establishment of security, intelligence and military infrastructures where their tools can reach to build and expand an Islamic republic is now bearing fruit, although it is considered poisonous in the eyes of the West, the East and many of its neighbors.

After hours of waiting, I finally got a call that there was a car waiting for me outside the hotel. It was driven by an armed man in military uniform, accompanied in the car by armed guards. As we headed to Al-Hajj’s house, my companion stressed the importance of maintaining his privacy and security. After more than 40 minutes of command through military checkpoints, we arrived at a heavily guarded villa. Al-Hajj welcomed me with the usual warmth of the Sudanese people, and joked to me, “Have you adapted to the heat of the atmosphere and the sound of bullets.”

We moved to a secluded corner of the backyard of the villa, away from home. The pilgrim dismissed all the guards. After stressing once again the importance of not mentioning his name or any details that may reveal his identity, we began our conversation on the issue of Sudan and Iran. Or rather, Hajj began to dissect the relations between the two countries while I was listening.

Al-Hajj began by saying that Sudanese-Iranian relations were strengthened by the military coup that brought the Islamic Front to power in Sudan in 1989, a period witnessed closely. The two countries were ideologically compatible, especially in their common hostility toward the United States. Iran supported the military coup and Omar al-Bashir as Sudan’s new president, and provided military and humanitarian aid throughout the 1990s. On the other hand, Sudan supported Iran’s ambitions in its nuclear program and voted against UN resolutions condemning Iran, especially in the areas of human rights.

Regarding the security and intelligence relationship between Iran and Sudan, Al-Haj explained that it began in the early 1990s under the leadership of Major General Dr. Mahdi Ibrahim, the founder of the Sudanese security system, along with Dr. Nafi Ali Nafi. At the time, Sudan’s security apparatus was divided into an internal security agency known as the National Security Agency and an external security agency overseen by Sudanese intelligence. However, in 2004, Bashir issued a decree to integrate all security services under a unified body called the General Intelligence Service

Mahdi Ibrahim is credited with his role as an engineer for security relations between Sudan and Iran. Iran has played a key role in shaping the Sudanese security and intelligence system, as it is designed along the lines of its own structure in terms of administrative management, training, and operations. In the early stages, all Sudanese officers and soldiers were sent to Iran for training. Similarly, Iran has sent its officers to Sudan to serve as experts and advisers within Sudan’s emerging intelligence service.

During this period, Iran supplied the Sudanese army with weapons and smuggled weapons to associated factions throughout the Middle East and Africa. Sudan has also become a training ground for extremists from around the world under the influence of Iran. In the end, Iran has set up factories to manufacture weapons on Sudanese soil.

To strengthen its influence on Sudanese society and religious life, Iran established Hosseiniyat (Shiite mosques) in Sudan, which served as a gateway to spread Shia Islam locally and across Africa. All this was done under the umbrella of the Iranian Cultural Center, which established 45 branches and schools, such as Al-Furqan schools that are still operating to this day.

There are no accurate statistics on the percentage and actual number of Shia Muslims in Sudanese society, but various studies indicate that they make up about 1% of the population, although this figure may change. According to a 2009 Pew Research Center study, the percentage of the Shia population in Sudan exceeds 1%, while updates to the 2020 Global Religions Database indicate that Shiites account for about 0.07% of the population. According to the State Department’s 2022 Religious Freedom Report, this small Shia community is mainly based in the capital, Khartoum.

However, official relations between the two countries ended on January 4, 2016, when Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour confirmed to Al Jazeera that Sudan had severed diplomatic relations with Iran due to its sectarian interference in the region and its attacks on the Saudi embassy and consulate in Tehran.

Al-Hajj believes that the severing of diplomatic relations between Khartoum and Tehran in 2016 did not weaken the Iranian influence in Sudan on the security, military and economic levels. This view is in line with the statements of a high-level Sudanese military source, whom I will call “the brigade.” The general confirmed to me that the secret relations between the two countries continued at the level of the security services, using a civil interface, the African Union of Digital Media, to cover these relations.

The Union, whose board of directors was headed by the wife of Major General Mohammad Atta al-Mawla, director of the Security and Intelligence Service, and the executive management of the union includes intelligence officers and its executive director is the security lieutenant colonel Ghada Abdel Moneim; he directly belongs to the director of intelligence and worked for three years (2016-2019) as a security and military channel that facilitates Iran’s operations in Sudan.

All Iranian military and security experts and advisers have been admitted under the guise of being EU-linked media personnel. This arrangement continued until the fall of the Bashir government in April 2019, where the union was dissolved and relations were cut, to resume again in 2020 under the supervision of the Sudanese military intelligence.

The Sudanese security community in 2016 provided a justification for the need to maintain military and security relations with Tehran, that Iran was a major part of the axis of resistance, and that they could not abandon this alliance, even if the political relations between Tehran and Khartoum ended. For this reason, the security and military institutions have worked to continue these relations for mutual economic and military benefits, and this began by enabling members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards involved in military industrialization in Sudan to train and provide Hezbollah and Hamas with the necessary resources in exchange for economic, military and intelligence support for Sudan.

After the revolution in Sudan in December 2018 and the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in January 2019, military intelligence and military security received the file of communication with the Iranians. Here, I find consistency between the novel of the pilgrim and the events and the novel of the general.

In a related context, it can be seen that the direct supervision of the relationship from the Iranian side was the client of Qassem Soleimani until his assassination in January 2020. After that, Brigadier General Ismail Qani took over the supervision. All contacts between the two sides were conducted through the Iranian ambassador in Beirut, Mojtaba Amani, who was injured in the explosion of communication devices in Lebanon on September 17, according to the Iranian Fars news agency. Al-Haj said that, given the pressure that Lebanon is suffering as a result of the superiority of Israeli intelligence over the country’s telecommunications infrastructure, it is possible that the point of contact between the two sides has been changed or reset to another location.

Despite the fact that the relationship has seen periods of ups and downs, the armed conflict between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces, along with the Gaza war, has given Tehran a chance to make Sudan a new platform for attacks on U.S., Israeli, and Arab interests.

Al-Haj stressed that Iran’s military and intelligence support was a decisive factor in resolving the battle for the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces. He believes that one of the decisive battles was a real turning point, as Iranian support enabled the army to achieve significant breakthroughs in the context of the battles, and this was especially evident after the army’s attack on Omdurman and its control of the radio and television building on March 14, 2024, which ended the control of the Rapid Support Forces, which has been in place since mid-April 2023.

With the dynamic shifts in Sudan and the changing balance of power, the armed conflict, which has escalated into civil war, has reshaped alliances within the country. The conflict led to the Islamists returning to high-profile positions, with their influence growing significantly as the war continued, as they were fighting alongside the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces, in particular the Brotherhood battalions associated with the Sudanese Islamist movement, known locally as Kizan.

Civilian politicians, including those from the Forces for Freedom and Change, a civilian and rebel alliance opposed to military rule, accuse Islamists of controlling the decision-making apparatus within the post-war military, and this has largely contributed to the failure of all international and regional efforts to launch dialogue and propose solutions to the civil war, whether through the Jeddah talks, the IGAD initiative, or the Egypt conference.

El-Hajj, who spent 40 years in politics, military service and participation in external security, said the course of the war has become unpredictable. Islamists are allied with Iran as a state and ideology, seeking to strengthen Tehran, protect its interests, and expand its influence. These relations deepened and overlapped further after the war in Gaza and the assassination of Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran on July 31, as well as a series of Israeli military strikes on Lebanon, which resulted in the killing of 18 Hezbollah leaders in a month, including Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah on September 27

All of the above brings me back to a 2012 book by U.S. intelligence officer Stephen O’Harn, titled “The Iranian Revolutionary Guard: The Threat That Grows as America Sleeps.” In the book, O’Harn asserts that Iran brought Osama bin Laden to Sudan after the IRGC struck a deal with Hassan al-Turabi (1932-2016), the leader of the Sudanese National Islamic Front, where Tehran would have provided millions of dollars to training and arms transfer centers that would turn Sudan into an Iranian starting point for the rest of the African continent.

Today, the Persian strategy of conflict — the export of extremism and terrorism, and the strengthening of the presence of rogue states — is being repeated, but with new methods and tools.

In this context, a source claiming that he met a group of US intelligence officers in the late 1990s and before the events of 9/11 and told them that Sudan would be a central focus of Salafist jihadism. During the Bashir regime, the Muslim Brotherhood believed that they had secured a country that ruled through the international organization of the Muslim Brotherhood and were planning to start from it to control other countries. Therefore, Iran considered Sudan early on as a strategic ally that would help it achieve its ambitions and export its revolution to Mecca, and redirect Muslims around the world to Iran, which it claimed would lead the Muslim world as a savior from the colonial face of the United States and the end of the State of Israel.

As midnight approached, fatigue began to appear on the face of the pilgrim. I politely suggested that he can rest and we’ll continue tomorrow. But he just smiled and said, “Can you guarantee that we will be able to hold this session tomorrow? Let’s continue. Maybe someone will read or hear.”

Thus, Al-Haj believes that not only have the main actors recently returned, but the circumstances are remarkably similar to those of Sudan in the 1990s. International and regional isolation has surrounded Khartoum, and the lack of trust between the Sudanese army and the various parties in the peace negotiations has become clear. The military’s need for new allies with experience in working within complex conflict environments, such as the Iranians, has increased, especially after the losses it suffered during the early stages of the war. Considering his battle against the RSF as existential, all these factors reinforce the influence of both Islamists and Iranians.

Thus, Al-Haj concluded that the conditions and actors are in place to re-establish the scene of the 1990s, but this time it is accompanied by a highly volatile and volatile African and Middle Eastern environment. To understand the implications of Iranian empowerment in Sudan, Al-Haj said the broader current landscape of Africa must first be studied. For example, the continent is undergoing rapid transformations, with increasing challenges to U.S. capabilities in the growing fight against terrorism there. These challenges have been exacerbated by four coups after 2020 in African countries: Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. After the withdrawal of U.S. forces in July 2024 from its counterterrorism air base in Niger, Central Africa has become a quagmire in which local governments are grappling against terrorist organizations such as ISIS and al-Qaeda, as well as sympathizers seeking to foment chaos.

The observation of Iranian activity in its early stages may not provide a careful reading of our current position. In this regard, the general stated: “Iran has been working in Africa for many years, and recently the Iranian marches reached Ethiopia during the government’s war with the Tigrayan Front between 2020-2022, and now it is working with the Sudanese army and I do not rule out that it is threatened to fall into the wrong hands.” He asserts that Tehran continues to support the Somali terrorist group Al-Shabaab and actively participate with the Islamic Movement in Nigeria, which acts as an Iranian proxy similar to Hezbollah, the Popular Mobilization Forces and the Houthis

This comes at a time when Tehran is increasingly needing to regain its centrality and its pivotal role in supporting Islamist groups hostile to the United States and Israel, especially in light of the ongoing conflict in Gaza. The failure of its missile attack on Israel on April 13 highlighted Iran’s inability to attack either country within its territory, reinforcing Tehran’s need to strengthen its capacity for operations and covert attacks while maintaining denial capacity.

As the African continent is teeming with jihadist fighters, Iran has the experience, knowledge, history of their organization and support through various means. Enhancing its influence in Sudan amid growing uncertainty and uncertainty would allow Iran to redevelop its infrastructure, enabling it to direct and organize these organizations and groups. In particular, this is likely to happen if the Sudanese army surrenders to external pressure and shifts from a national institution to a body with different military groups similar to the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq, effectively becoming Tehran’s agent. In such a scenario, Sudan could return as a rogue state that threatens regional stability, and represents a military and security threat to all neighboring countries, specifically referring to Egypt and Saudi Arabia as Iranian targets in the medium term.

Red Sea: The complex of the safe passage between Iran and its interests in Sudan

I have often reflected on Iran’s strategy of approaching and assisting countries, especially in times of armed conflict. This strategy includes providing support that gives the affected party a sense of importance and its ability to change the balance of deterrence and strength, allowing Iran to impose its conditions on other demands. This is exactly what happened in Sudan.

Al-Hajj told me that Iran’s open appetite for expansion and growth in Sudan is not only governed by the current circumstances and the realities of war, but also realizes Sudan’s important geopolitical position in the Red Sea environment. In 2012, Iran offered to help Sudan establish air defenses along the Red Sea coast after an airstrike that Israel was accused of carrying out.

Here comes the role of the Houthis in the development of infrastructure through the Iranian concept. Al-Haj noticed that the actual relationship between Sudan and the Houthi movement began five years later from the so-called Operation Decisive Storm, which began on March 25, 2015. The main topic of discussion between the two parties was the Sudanese prisoners in Yemen.

Sudanese intelligence was managing contacts with Brigadier General Yahya Sari, the Houthis’ official spokesman, and Mohammed Abdul Salam, the chief negotiator, as well as Abu Maytham, the Houthi movement’s foreign security director who was originally based in Beirut. It is currently unclear whether there is still a change in Israeli contact points and strikes targeting well-known leaders as part of the axis of resistance, or whether it has moved elsewhere.

Referring to the brigade believed to be in 2020, Sudanese intelligence took over the communications file with Iran, specifically with the Revolutionary Guards. During that period, a set of understandings were reached stating that the Houthis would not target Sudan militarily. In return, the Sudanese Military Intelligence and the General Intelligence Service, with the approval of Major General Burhan, agreed to allow the smuggling of weapons to the Houthi movement through the Red Sea under the supervision of the Sudanese intelligence, and to facilitate the movement of the Houthis through Khartoum airport to travel outside Sudan after their arrival from Yemen through the Red Sea; this includes facilitating the arrival and transfer of 17 Houthi leaders from Khartoum Airport with three separate flights to Beirut, as well as treating the wounded Houthis in Sudan.

In late 2021, the relationship between the two parties developed, with a focus on effectively smuggling drone engines to Houthi traffic through the Sudanese Red Sea port of Flamengo. Smuggling shipments included precision spare parts and ballistic missile guidance technology arriving via fishing boats anchored in the port of Port Sudan. In addition, the number of Houthis smuggled from Sudan to Beirut has steadily increased to at least five people per week.

Al-Haj believes that Sudan’s facilities for the Houthis and Iranians have contributed to the development of relations leading to the agreements to provide Sudan with drones and train some officers of the Sudanese Armed Forces. This culminated in early 2024 with the official restoration of full relations between the two countries, as well as increased intelligence and military activities.

The pace of Houthi attacks has begun to take a new turn, since it entered the fifth phase, according to their media, in terms of the pace of targeting commercial ships in the Red Sea, and the movement began to document its attacks. On 3 October 2024, the Houthi military media showed scenes showing the targeting of the British oil tanker Cordelia MOON in the Red Sea, using a drone, which reveals a new media data aimed mainly at promoting their ideologies and proving the effectiveness of their military option, despite its failure to stop the war in the Gaza Strip.

Al-Hajj continues to recount events in an attractive way, trying to historically link the goals of each event to the events that follow. After the official restoration of relations between the two countries, a senior security officer tasked with overseeing Sudan’s drone project, Major General Sadiq, who once served as the director of Major General Burhan’s office, traveled to Tehran twice this year, where the old agreement on arms smuggling – the trade of drones and precision missile guidance equipment to the Houthis – was confirmed.

Moreover, Iran has been granted a military base in the Red Sea, ensuring the flow of weapons and military equipment to Hamas. There was also an agreement to deploy a Sudanese liaison officer in Eritrea to facilitate smuggling operations across the Red Sea, as well as an understanding that the Sudanese Armed Forces stationed in Saudi Arabia would not deal with the Houthis, while providing all the necessary support and facilities to target Khalifa Haftar’s plans in Libya.

To verify the information of the pilgrim and the narrative he provides, it was necessary to consult the brigade, who confirmed that by the end of January 2024, two Migron-6 drones had entered service and started operating from Wadi Base, one of the largest military bases in Sudan. These drones are currently involved in military operations.

During the same period, an Iranian ship arrived at the port of Port Sudan carrying four Muhajir-6 drones, along with five 130 mm artillery pieces, six 120 mm mortars, and a large range of various munitions. Fishing boats crossing the Red Sea are widely used to smuggle weapons, often loaded with fish on the surface while hiding between 600 and 800 assault rifles under the deck, he said. Moreover, larger fishing vessels also carry various types of missiles and spare parts for drones.

He said that after the relationship between the two countries became normal and direct, Iran, through the Sudanese military manufacturing authority, provided 300 thousand fully equipped military uniforms and monitoring and spying equipment for the Sudanese army.

With regard to securing the transfer of weapons and military equipment to Hamas, there was coordination between the military intelligence and the Sudanese intelligence to draw on the expertise of the Rashaida tribe, which had settled in the Sudan in 1846. Weapons and military experts are smuggled from Sudan through the Sinai desert, in coordination with some tribes inside Egypt, to the tunnels leading to Gaza. In this regard, the general, who respects the Egyptian leadership and greatly appreciates it, questions its decision to support the Sudanese army, as it says, “Egypt supports the Sudanese army in its fight against the Rapid Support Forces, out of its need to achieve stability in Sudan and the position of the Sudanese army supporting Egypt in its position on the Renaissance Dam, along with the historical relations of the two parties.” He then adds, “But today Cairo faces a major challenge in preserving its interests with the Sudanese army after it was pushed by the war to ally with the Iranians and Islamists who have gained great influence within the army, especially since Cairo has suffered for decades from radical Islam and from the projects of the Muslim Brotherhood against the Egyptian political system, which is very intersected with the Iranian project, whether towards the region as a whole, or Egypt in particular.

Therefore, Cairo must determine its position and assess the repercussions of the Sudanese army’s restoration of control over the country’s geography, which may lead to the presence of a radical Islamic force that may feed the ambitions of the Muslim Brotherhood to rule in Egypt, and the attempts of terrorist organizations to restore their former presence in Sinai. The general took a deep breath, looked me right in the eye and said firmly: “Egypt must resolve this battle and take the lead from the Iranians.”

For a specialist researcher who wants to check the sources, it was necessary to find someone inside the Sudanese Foreign Ministry who could discuss the visits of the Sudanese Foreign Minister to Tehran, the first of which was on February 5, 2024. During my time in Khartoum, I wanted an active diplomatic meeting working on foreign affairs, and therefore, through research and mutual friends, one name has repeatedly emerged in diplomatic circles, which I will refer to as “diplomatic.”

He stated that the delegation accompanying the minister included representatives from the Military Intelligence and Security Service and the Al-Baraa Ben Malek Brigade, which is also known as the Al-Baraa bin Malik Brigade or the Shadow Brigades. This armed group has an ideological extremist affiliation and maintains a network of relations with Sudanese armed groups that cooperate with the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces.

The diplomat also noted the existence of an implicit and direct agreement between the Iranian Revolutionary Guards, the Sudanese General Intelligence Service and the military intelligence that allowed both countries to withdraw from the agreement. Al-Baraa Bin Malik Group was tasked with carrying out armed military operations in the Red Sea, while maintaining contact with the Revolutionary Guards similar to that of Hezbollah and the Houthis, as well as some factions in Iraq.

This is in line with what the brigade told me: “A number of members of the Al-Baraa bin Malik Battalion have been trained to operate drones and naval boats booby-trapped in Iraq and Lebanon.” In addition, the foreign minister’s visit to Tehran resulted in an agreement to set up a production line for drones and suicide boats in Port Sudan under Iranian supervision to supply the Houthis and Hamas with this type of aircraft. In contrast, Iran was granted one million acres of agricultural land from Sudanese land.

As soon as the name of the Al-Baraa battalion appeared alongside a group of extremist armed groups, many questions appeared in my mind that contribute to understanding the security chaos in the Middle East and Africa, which will continue to be exposed. It was necessary to ask about the presence of ISIS: is it already on the ground and fighting alongside the Sudanese army? Do you receive generous funding and have access to new military technologies?

In this regard, several sources I spoke with agreed that the relationship between the Sudanese Islamic Movement and extremist Islamist groups is close and advanced. At various times, these groups provided funding, training, protection and intelligence. Through institutions such as the Quran Society, the Islamic Call Organization, the University of Africa, the Islamic University of Omdurman, the Charm of Communication, the Madkar Organization, and the Union of Foreign Students, they have provided a ready infrastructure to engage in the ideas of the terrorist organization ISIS, which has played a public role in military operations since the beginning of the war. This is illustrated by the confession of politician Muhammad Ali al-Jazuli, who is also secretary-general of a Sudanese Islamist group, when he was arrested by the Rapid Support Forces in May 2023.

In analyzing the landscape of extremism in Sudan and tracking the movements of wanted extremists, it appears that a large number of ISIS members from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan – estimated at 6000 – have been invited to fight alongside the Sudanese army under the guise of studying at Sudanese universities.

Moreover, a researcher specializing in countering violent extremism in Sudan told me that a man named Saddam, who uses the code name “Abu Abdullah,” lives in Sudan. Despite his involvement in the killing of U.S. citizen John Granville and Abdulrahman Abbas Rahma on January 1, 2008, Saddam was not captured, smuggled into Iraq, Syria and Libya, and is now fighting alongside the Sudanese army in Omdurman, the country’s second-largest city.

When I gave the information I had to the pilgrim, asking for confirmation or denial, I was surprised when he told me, “If you want to become rich, just show the Americans Sudan.” In a cynical way, he added, “Do they even know about us?” He then explained that most of the individuals wanted under the U.S. State Department’s Justice Rewards Program are here in Sudan – including al-Desouqi, nicknamed “Khomeini”; Sheikh Jibril, Imam Bilal, and Hashim Arabi, a former colonel in Syrian intelligence; and Hisham al-Tijani, the head of students at the Institution of Students coming to Sudan, all of whom were active members of the terrorist organization Daesh.

During my stay in Khartoum, I met with one of the diplomats active in foreign affairs. As is often the case, everyone in this country wants to find a way out of the crisis and to convey messages to the world, but they fear assassination. The diplomat tried to explain why. “In the run-up to the outbreak of the war in Sudan, there were attempts by the head of the military council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, to improve relations with the moderate countries in the region and to cleanse the country of Bashir’s legacy and the Islamic Front. In October 2020, Khartoum agreed to normalize relations with Israel, and two months later the United States removed Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism. But that has not lasted, Sudan is a country where all contradictions are gathering, and the future cannot be planned because of the data, the intertwined data, the complexities and the multiplicity of actors who come from different and often conflicting backgrounds.

I tried to reach out to anyone from the RSF to get their story and their perspective on what was happening in Sudan, but I didn’t succeed. In fact, I was strongly warned not to contact them because of the complexities of the situation. They warned me that asking questions and possibly misinterpreting their understanding of my position could lead to “challenges” that would be difficult to deal with.

How to analyze the implications of Iranian control over Sudan

Iran’s clear ambition to control Sudan has serious and long-lasting consequences for the security and economic interests of the United States and its partners from Arab countries, especially Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Iranian control of Sudan will turn it into an active and influential state regarding the fate of the vital trade corridor of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan and Israel.

The negative effects of Iran’s presence are evident in the recent military activities of the Houthis, who now have a route to smuggle weapons, transfer of command, advanced technology and spying equipment, forming a new terrorist center that will be difficult to dismantle. Moreover, the geographical depth of the Iranians and the Houthis is increasing. Given that Sudan is Africa’s gateway, Iranian influence will continue to expand there.

The idea that the Iranian-Sudanese agreements allowed Tehran to take full control of the Red Sea, threatens both maritime navigation and the Arabian Sea. Thus, Saudi Arabia’s interests are exposed to multiple levels of military, security and economic risks. This includes development projects under Saudi Vision 2030, where the Saudi coastline along the Red Sea plays a pivotal role, as well as the NEOM project and the development of the Red Sea Coast project, both part of Saudi Arabia’s plans to diversify its economy away from dependence on oil by positioning itself as a hub for tourism, entertainment and foreign investment.

In addition, there is a direct impact on the Egyptian economy, managing the Suez Canal with 15% of international shipping traffic, 30% of container trade worldwide, and 40% of trade between Europe and Asia. Suez Canal revenues fell sharply due to Houthi attacks, reaching about $2 billion during the fiscal year 2023-2024, as ship traffic shifted around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope

In the same context, the Iranian-Sudanese rapprochement contributed to Sudan’s distance from supporting Saudi interests. As previously reported, Sudan stood in solidarity with Saudi Arabia and cut ties with Iran after the storming of the Saudi embassy in Tehran in 2016. However, it has become clear that Sudan’s support has been superficial and dishonest. In addition, Sudanese forces participated in the Saudi campaign against the Houthis in Yemen, which also appeared to serve Iranian interests.

We are facing a major shift in the expansion of Iranian influence in Sudan, which poses a geographical danger to Saudi Arabia. This could be Iran’s ultimate goal. The Sudanese military’s lack of seriousness in responding to Saudi pressure to stop the war only increases turmoil in the Red Sea and negatively affects Saudi national economic and development projects.

Moreover, the expansion of Iranian influence in Sudan increases pressure on his army and weakens his position against the establishment of an Iranian naval base, especially given the intensity of the civil war, which increases the army’s need for Iranian support. This will put the IRGC on only 200 miles (320 kilometers) from Saudi shores. Also, the presence of an Iranian naval base will enhance Iran’s intelligence and reconnaissance capabilities in one of the world’s busiest sea lanes. Imagine how much more Iran can achieve than it plays in providing the Houthis with data on passing ships, enabling them to successfully carry out their attacks.

Conclusion

Today, after many interviews with people whose names have been reserved for their protection and safety, I believe that we are about to confront a violent extremist terrorist axis targeting all countries in the world that are not in line with the Iranian project.

In the case of Sudan, its maritime border could place the Red Sea at the mercy of Iranian-backed terrorist groups. It would be unrealistic for the United States to turn a blind eye to this threat, especially at a time when it has mobilized a large part of its naval military force to combat Houthi threats to international navigation. The Houthis have gained support and assistance from Iran, especially in their use of missile and drone arsenals against military and commercial ships, as well as Israeli targets. Iran continues to seek to influence the dynamics of the Red Sea, by influencing the Bab al-Mandab Strait and establishing a foothold along its coasts.

Moreover, Iran’s growing presence in the Red Sea poses an existential threat to energy supplies and utilities, which was a former target for Iran when it enabled the Houthis to target Saudi facilities in Abqaiq and al-Khurais in 2019. In addition, the Houthis attacked several oil tankers in the Red Sea during the escalation accompanying the war in Gaza. In February 2024, the British cargo ship Rubymar was hit by a Houthi ballistic missile off the coast of Yemen, threatening an environmental disaster due to a possible 18-nautical-mile oil spill.

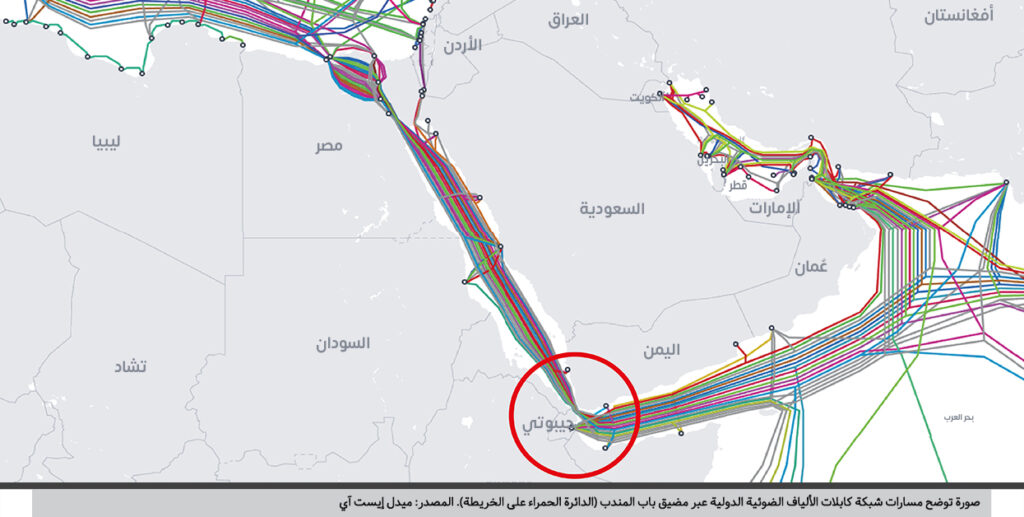

However, Iranian and Houthi activity in the Red Sea has implications that extend beyond commercial and energy security. There are real concerns about threats to global digital infrastructure, as underwater cables could become targets for Iran and its customers. The Red Sea floor hosts 16 fiber-optic lines, which together account for 17% of all international data transmission lines. “The threat from the Houthis to cut underwater cables is dangerous,” a military source said, “and it has been discussed between Sudanese intelligence and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards.”

Moreover, the Houthis’ control extends to the Bab al-Mandab Strait, one of the three bottlenecks around the world, connecting Europe, India, and East Asia. Contrary to false assumptions that the Houthis lack the technical and military capabilities to damage underwater cables, they have shown remarkable superiority during their involvement in the war in the Gaza Strip, especially after targeting Israel in mid-September 2024 with a “hypersonic” missile, which covered a distance of 1,300 miles (2040 kilometers) in 11 and a half minutes, according to Houthi military spokesman Yahya Sari.

On the other hand, cutting underwater cables, usually thickened by garden hose, does not necessarily require any special experience, trained staff or even professional divers. Some cables are located in the shallow water only at a depth of 100 meters. Do not forget that three divers were arrested in Egypt in 2013 for trying to cut an underwater cable near the port of Alexandria.

The risk of damaging underwater cables is perhaps more threatening than maritime piracy. The Red Sea carries an estimated 17 percent of global internet traffic along its fiber tubes, making it a rich target for the Houthis. Damage to these cables can have enormous consequences for the global economy, as well as civilian, military and financial information services.

The alarm bells were launched in December 2023 when Houthi-linked Telegram channels published a map of underwater communication cable networks in the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Arabian Sea and Gulf with the threat: “Yemen appears to be in a strategic location, with internet lines connecting entire continents near it – not just countries.”

Another channel linked to Lebanon’s Hezbollah published a post asking: “Did you know that the internet lines connecting East and West pass through the Bab al-Mandab Strait?” This prompted the launch of a five-bell alert by telecom companies regarding possible sabotage by the Houthis.

However, the risks to underwater cables may not necessarily stem from deliberate actions. The fierce naval war in the Red Sea by the Houthis could inadvertently damage these cables. When the British cargo ship Rubymar, which was hit in March this year by a Houthi missile attack off the coast of Yemen, was hit by its crew and thrown an anchor in deep waters. This has trapped the anchor with three underwater cables and pulled them along the seabed, disrupting the internet connection of millions of people, from nearby East Africa to thousands of miles away in Vietnam.

Finally, it is important to highlight the humanitarian cost of the war. According to a report by the International Rescue Committee, since April 2023, the ongoing war has killed 150,000 people, a much higher number than the officially announced death toll of 15,000. Moreover, 12 million people have lost their homes, with 10 million citizens displaced inside Sudan and another 2 million fleeing to neighbouring countries. In addition, 18 million people face severe food insecurity amid food shortages, water, medicine and fuel.

All of the above only raises the question of Iran’s intervention in Sudan and its ability to help the Sudanese army achieve victory and regain control of the country. It also raises the question that has never been asked whether the United States and Middle Eastern countries are willing to bear the consequences of Iranian intervention in another conflict in the region, especially in a country with a coastline of nearly 670 kilometers along the Red Sea.

This question was the only one that the pilgrim, the general and the diplomat did not even try to answer, except by reducing their shoulders to express their despair and fatigue with the world.

During the editing and review of this article, on October 1, Iran fired 180 ballistic missiles at Israel in response to the assassination of Hamas political bureau leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran, and Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut. At the time, Hezbollah was facing structural, logistical, and organizational challenges due to Israeli strikes targeting its commanders and weapons storage sites.

The recent Iranian attack may differ from its compound attack on April 14, in terms of the extent of the arrival, which took about 15 minutes, and in terms of the few intercepts of missiles compared to the first attack, which was shot down during about 99% of flying objects, as well as the targeted sites that are directly linked to the course of the war in the Gaza Strip and Lebanon, and achieved the element of surprise, as Iran entered before it in a state of complete silence, and its indicators were monitored by the United States and Israel hours before its implementation.

This brings us back to the idea that the space given to Iran through Sudan’s gateway contributed to the development of its missile program. What will the pilgrim, the general, the diplomat say? I think they will agree with me that October 1st is just a fatal example of how Tehran has benefited from the period of freedom of movement it has enjoyed in Sudan in recent years