This report discusses jihadist expansion in the Benin-Niger-Nigeria borderlands, focusing on ISSP and JNIM strategies and impacts.

Since early 2024, the violent campaigns of the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) jihadist groups have been reshaping the security landscape in the Sahel and its littoral borderlands. These groups have significantly expanded their operations, transforming the regions bordering the Sahel toward the coast, often called coastal West Africa or “littoral borderlands,” into an active conflict hotspot. ACLED data show that JNIM and ISSP have entered a new phase of expansion, and their growing influence in the border regions between Niger, Nigeria, and Benin is part of a broader regional trend of jihadist expansion, and consequently, a larger proportion of the civilian population being exposed to conflict.

In recent years, these border regions have experienced a considerable surge in violence. Niger’s Dosso and Tahoua regions and Benin’s Alibori department are three of the most affected areas. In these regions, ACLED data indicate that since 2023, the number of reported incidents of political violence has increased, and associated reported fatalities have doubled. JNIM and ISSP’s investment in cross-border activities suggests that this border region is of growing importance for jihadist expansion. The groups have been exploiting the porous borders to entrench their presence and further their goals of establishing proto-states, but also to complicate military efforts to contain their areas of operation. These ongoing developments unfold against the backdrop of significant geopolitical changes, including regional alliance shifts and the severing of ties with former Western partners.

The emergence of a new battlefront

Jihadist expansion from the traditional strongholds in the central Sahel can be traced back to at least 2016, when JNIM’s predecessor groups Katiba Macina and Ansaroul Islam and ISSP predecessor Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) extended their radius of operation to the north of Burkina Faso and Niger. This shift marked a significant transformation in the structure and goals of these groups. JNIM, which was founded in March 2017 as part of a merger of four preexisting groups (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb’s Sahara Emirate, Al-Murabitun, Ansar Dine, and Katiba Macina), began pursuing a strategy focused on building local alliances. This happened in stark contrast to the approach of ISGS, which mirrored the violence and brutality of its parent organization, the Islamic State. In late 2017 and early 2018, JNIM and ISSP further expanded to southwestern Niger and eastern Burkina Faso, areas that would play an important role later on with the expansion into coastal West Africa.

However, deepening ideological differences and mounting competition between the jihadist groups began generating mistrust and animosity.1 By mid-2019, this escalated into an outbidding campaign characterized by parallel offensives against state forces,2 but also the first spillover incidents involving JNIM and ISSP (the then Greater Sahara faction of IS West Africa Province) in Benin and Nigeria.

In early 2020, the growing rivalry between the two groups led to a violent turf war in central Mali and in the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger borderlands, known as the Liptako-Gourma region. At its outset, JNIM consolidated its influence in central Mali and most of Burkina Faso, including the eastern regions, effectively pushing out ISSP. Meanwhile, ISSP solidified its presence in the Liptako-Gourma tri-state border area.3 Using eastern Burkina Faso as a base — specifically Kompienga, Tapoa, and Koulpelogo provinces — JNIM expanded its operations southward into Benin and Togo starting from 2021 and 2022.4

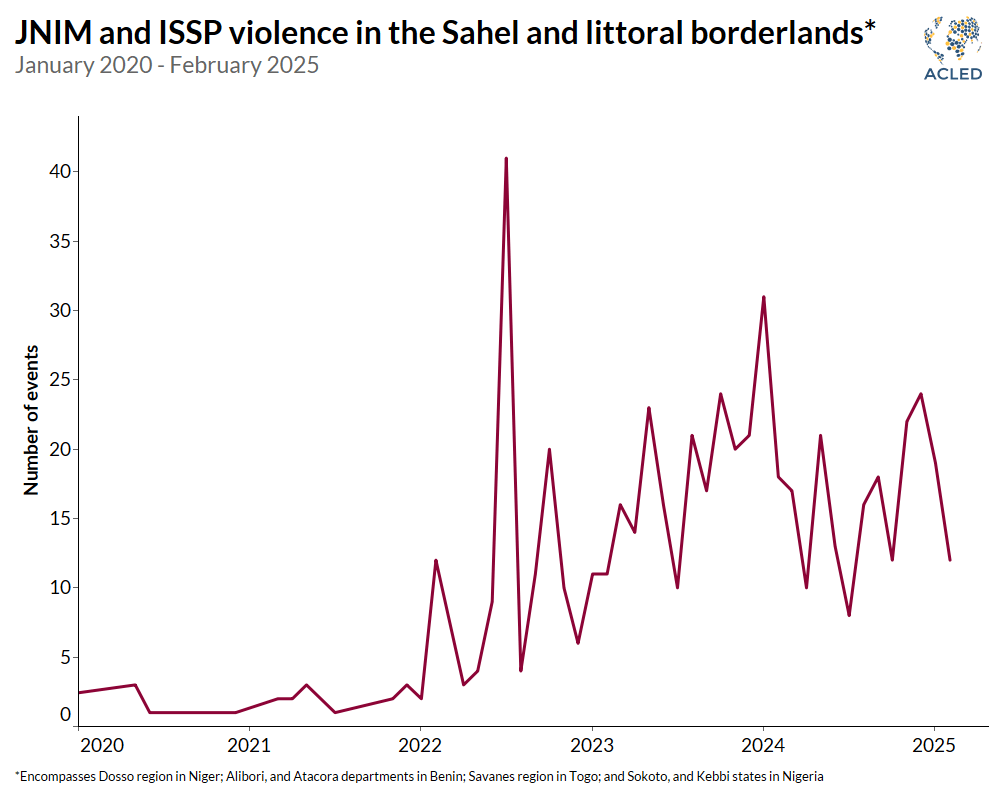

Between 2023 and 2024, JNIM and ISSP have escalated their operations in the border regions between Benin, Niger, and Nigeria, significantly transforming these areas into a volatile frontline (see graph below). This renewed southward expansion through sustained violent campaigns is driven by the persistent pursuit of new manpower and recruitment opportunities as these groups continue to grow and build their insurgent armies,5as well as the need for access to resources through smuggling and illicit trade routes essential for their operations. Expansion into these remote and less secure areas further allows both groups to establish new operational bases and expand their logistical networks. This expansion has led to territorial contestation and has profoundly impacted the local communities, who find themselves increasingly caught in the crossfire of the ongoing conflict.

How JNIM and ISSP expand southward

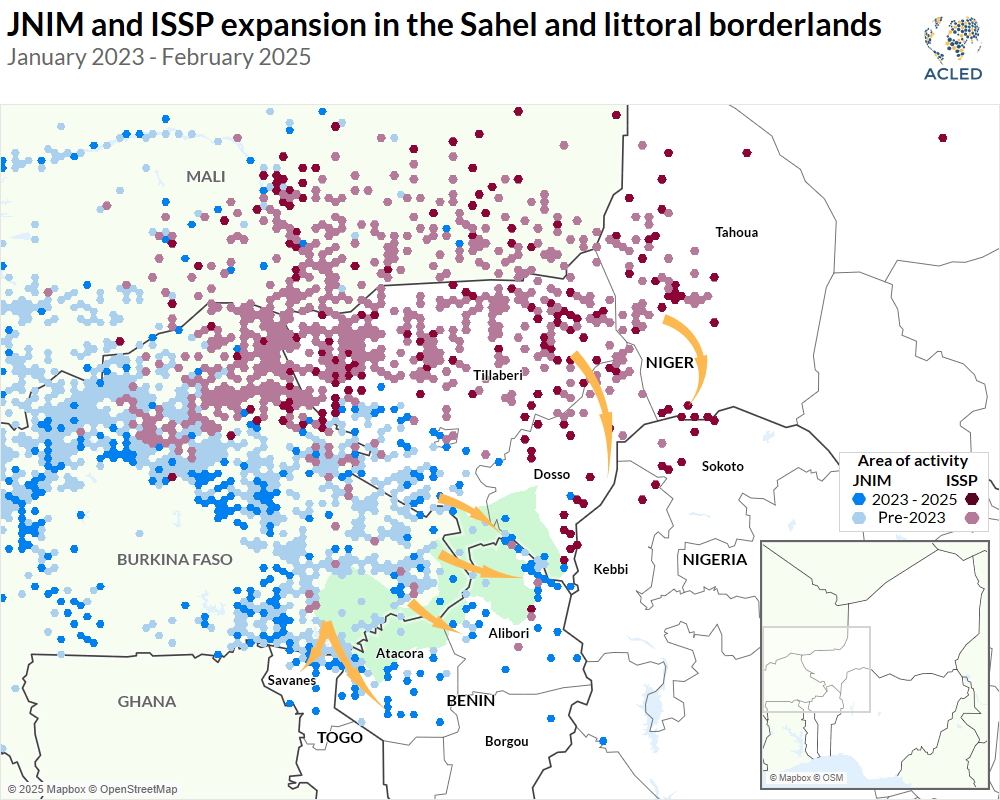

Violent attacks by JNIM and ISSP have significantly increased in the border areas between the Sahel and the littoral borderlands, each using different tactics. Both groups have expanded out of their traditional areas of operation in the Sahel toward Benin and Nigeria, crossing paths in the southwestern border regions of Niger (see map below).

JNIM has used eastern Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger as staging grounds to initially expand into Benin in 2021 and in Togo in 2022, and since the beginning of 2024 consolidating its presence in northern Benin and southern Dosso in Niger. In northern Benin and southern Dosso, JNIM has entrenched itself within the W-Arly-Pendjari Complex protected area, including Park W, from where the group has staged its campaign along the Benin-Niger border, which has also facilitated movements toward Nigeria.6JNIM has used media and propaganda campaigns to promote its presence, and has claimed several operations in Benin, Niger, and Togo.7

ISSP, which originates and operates from its strategic bases in northeastern Mali’s Menaka and Niger’s Tillaberi and Tahoua regions,8 has instead intensified its activities in northern and central Dosso and introduced tactics of economic warfare, in particular through attacks on the Benin-Niger oil pipeline. ISSP’s strategy initially involved primarily nonviolent activities, including collecting zakat (alms or taxes), clandestinely managing supply lines, and moving forces and reinforcements across Dosso’s hinterland into Nigeria. Several routes across Dosso initially constituted a supply corridor for the group before ISSP developed it into a support zone. In early 2024, it transformed into a combat zone as the group began launching attacks on security forces, civilians, and critical infrastructure.

Certain media narratives have misleadingly attributed the surge in violence along the Niger and Nigeria border to a “new terrorist group” known by the moniker “Lakurawa.”9 Rather than an altogether new group, these militants are also reported to have long entertained relations with ISSP, exploiting the chronic instability in the central Sahel.10 In fact, attacks attributed to the so-called Lakurawa are long-established ISSP operations in Niger’s Dosso region and Nigeria’s northwestern states of Sokoto and Kebbi.11 This mislabeling overlooks how groups like JNIM and ISSP operate and adapt to changing circumstances when they infiltrate, contest, and consolidate territory, and also employ hybrid tactics that mix self-defense, insurgency, and banditry — complexities that oftentimes are poorly understood or described in oversimplified or outdated terms in official accounts and the media.

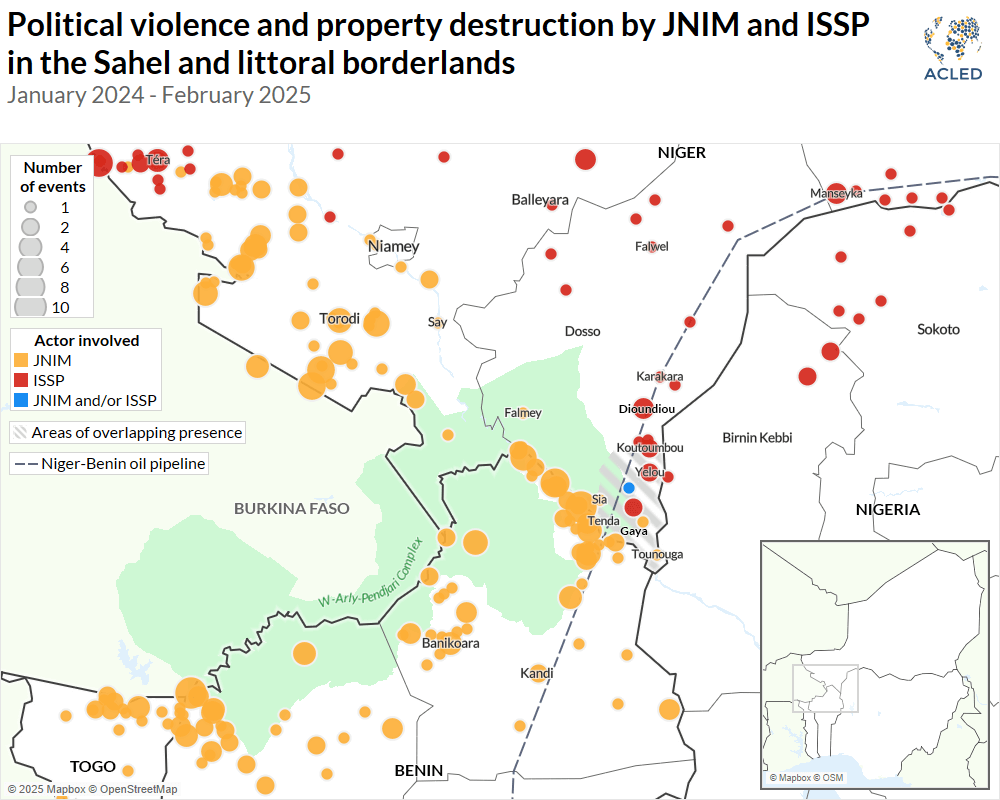

ISSP has maintained a low profile, operating covertly to infiltrate and entrench itself along the Niger-Nigeria border, and is now also expanding its operations toward the Beninese border.12 The expansion of JNIM and ISSP follows different geographical trajectories but the two groups’ presence overlap in Niger’s Dosso region, and especially in the communes of Gaya and Dioundiou (see map below). JNIM and ISSP’s overlapping presence in the same areas creates a complex and volatile situation due to their different operational and violent tactics and objectives.

For example, JNIM has carried out a series of attacks on military and security force positions,13including focusing on embedding itself in communities on both sides of the Benin-Niger border through proselytization, community outreach, and involvement in the local economies and illicit trade. Meanwhile, ISSP has carried out similar attacks by engaging in armed confrontations with the military and security forces. What stands out, however, is its more aggressive approach and use of economic warfare, targeting the oil pipeline, in particular the section between Bela and Lido that passes through the Dioundiou commune.14Additionally, in a more recent development, the group also began targeting civilians on a larger scale, including by committing mass atrocities, as happened on 22 February 2025, when likely ISSP fighters attacked several villages around Koutoumbou, in Diondiou commune, on the border with Nigeria.

Both JNIM and ISSP operate in Gaya, creating a competitive dynamic as both groups vie for influence and control over the same geographical area. It cannot be ruled out that in these early stages of infiltration and territorial contestation, the two groups could establish a modus vivendi by coexisting or demarcating their respective areas of operation in the process of destabilizing the territory. Either way, considering the enmity, and the protracted and deadly turf wars between JNIM and ISSP elsewhere in the region, this proximity more likely increases the risk of broader competition and confrontation.

Territorial contestation and the social impact of militant expansion

The expansion of JNIM and ISSP in the Sahel and littoral borderlands is interwoven with significant changes in the social dynamics within the affected communities. As these groups consolidate control over new areas, they interact with the civilian population, influencing social norms and economic activities.

In northern Benin and Niger’s Dosso region, interactions between jihadist militant groups and local populations have evolved as the groups transition from transitory movements to a more entrenched presence.15 Initially, militants moved through these areas, often without engaging with the civilian population. This shift is characterized by the strategic use of religious outreach and community engagement, which includes setting up camps and stayovers near villages, conducting recruitment drives, and preaching at local mosques and participating in religious activities.16 Such interactions serve both to embed the militants within communities and to propagate their ideology.

JNIM, in particular, has been noted for its overt religious messaging, which often includes warnings against collaborating with military and security forces. This messaging strategy not only aims to integrate the group’s presence into the daily lives of the locals but also to establish a set of rules for engagement between civilians and militants.17The presence of militants in public spaces, particularly in mosques, underscores their intent to cement their influence by becoming a regular part of community life.

Economically, areas under the influence of the militant groups increasingly revolve around the groups’ logistical needs. In parts of northern Benin, local economies have started to cater more to the militants, facilitating illicit trade and smuggling operations that include the provision and procurement of fuel and supplies.18The militants’ involvement in local commerce is often coercive: They set the terms of engagement and integrate their operations into the local economy under the guise of protection and order.

Moreover, the coercive nature of these groups’ interactions with civilians often involves setting strict behavioral guidelines based on their interpretation of Shariah, with severe consequences for noncompliance. These activities are not only a means of control but also serve as a mechanism for the militants to sustain their operations through economic exploitation and integration into local markets.

Increased violence in the region is often caused by fighting over territory as the jihadist groups expand their control. A group’s strategic encroachment into new areas is often met with resistance from local security forces, which seek to regain or maintain control, leading to a cycle of aggression and retaliation through militant attacks and military counteroperations that further destabilizes the region. In areas with limited state presence, civilians have taken up arms to defend their villages by forming self-defense groups — a pattern observed elsewhere in the region — including the zankai in Niger’s Tillaberi, Tuareg and Arab militias in Tahoua, and the Yansakai in northwestern Nigeria.19 Militiafication usually creates a conflict dynamic that exacerbates underlying ethnic tensions through the arming of communities and the militarization of identities, escalating localized violence into full-fledged intercommunal wars. As JNIM and ISSP continue to expand their reach, the impact on local communities grows more profound, affecting everything from cultural practices and economic activities to local governance and security.

Confronting persistent regional challenges

In light of continued jihadist expansion and escalating cross-border insecurity, the recent announcement by central Sahel states to form a 5,000-strong joint force underscores the urgent need for increased regional cooperation.20 While the central Sahel countries of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger that have withdrawn from Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are now driving this initiative, previous efforts, including the defunct G5 Sahel Joint Force and other regional initiatives, illustrate the persistent challenges in conducting and sustaining effective joint operations.

Strained relations between neighboring countries, particularly between Benin and Niger and between Niger and Nigeria, have already hampered coordinated security efforts and allowed jihadist groups to exploit these border areas amid heightened political tensions, including those following the July 2023 coup in Niger. Against this backdrop, the proposed joint force aligns with the objectives of the central Sahel states (fighting rebellions and insurgencies and repelling external military aggression), which have already formed a defense pact and confederation. However, the joint force initiative is not designed to bridge the existing divides and deal with a wider geographical threat area that now encompasses several neighboring littoral states.

In 2021, multiple coordinated military operations demonstrated a remarkable level of regional cooperation. Operations such as the G5 Sahel Force’s Operation Sama in Niger and Burkina Faso; a series of joint operations between Burkinabe and Nigerien forces known as Operation Taanli; and Operation Tourbillon Vert involving Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, and Mali demonstrated an impressive range of cooperation across a vast geographical area.

However, military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger between 2020 and 2023 significantly disrupted the potential for sustainable, coordinated responses. These political upheavals not only destabilized regional cooperation but also led to a shift in international partnerships. The withdrawal of Western military support from France (in August 2022),21 Germany (August 2024),22 and the US (September 2024)23 and the Malian authorities’ decision to end the peacekeeping mission MINUSMA (which officially ended in June 2023)24 has further created a vacuum that jihadist groups have been quick to exploit. This has largely shifted the burden of the fight to regional forces, which have struggled with logistics, coordination, and sustaining pressure on militant groups. The jihadist expansion and ongoing entrenchment along the borders between Benin and Niger and Niger with Nigeria illustrates the persistent lack of effective regional security strategies and the difficulties in achieving cohesive action against jihadist groups.

The future stability of the border area between Niger, Nigeria, and Benin depends largely on the responses of these states, especially their ability to improve military and security cooperation and coordination. If these efforts continue to falter and the presence of military and security forces declines, there is a risk that the local population, influenced by other communities in Niger and Nigeria that reject militancy and banditry, will take up arms in self-defense. Such a development would not only change the current conflict dynamics, but could also fundamentally reshape the security landscape in this subregion.