The Critical Threats Project’s Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Sudan. The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has committed numerous war crimes as the group has intensified its efforts to consolidate control over western Sudan since losing Khartoum in March 2025. The RSF recently attacked the Zamzam refugee camp, where it likely committed war crimes, near the North Darfur state capital, al Fasher. These actions are possibly constituent acts of ethnic cleansing or even genocide as defined under international law. An RSF attack on al Fasher would likely lead to further acts of ethnic cleansing and possibly genocide.

Somalia. Al Shabaab captured two key areas in central Somalia that could enable the group to reestablish support zones there and connect them to its center of gravity in southern Somalia. This would undo the US-backed Somali counterterrorism offensive in 2022 and allow al Shabaab to pressure the remaining federal government-controlled areas in central Somalia. This comes as al Shabaab opened a second front south of Mogadishu in March 2025.

Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pro-Congolese Wazalendo fighters attacked M23 positions in North Kivu and South Kivu provinces, likely to undermine the group as a governing force and weaken its negotiating position with the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The attacks highlight M23’s capacity and supply issues, which limit its ability to consolidate control in some areas. This coincides with the M23’s continued struggles to effectively implement its political agenda in the eastern DRC.

Sahel. The latest diplomatic tensions between Algeria and Mali could strain the Algerian relationship with Niger and Russia. These tensions will test the cohesion of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), as Niger is in a difficult position between Algeria and the AES. Algeria has separately increased cooperation with the West in recent years, likely in response to destabilizing Russian activity around Algeria.

Assessments:

Sudan

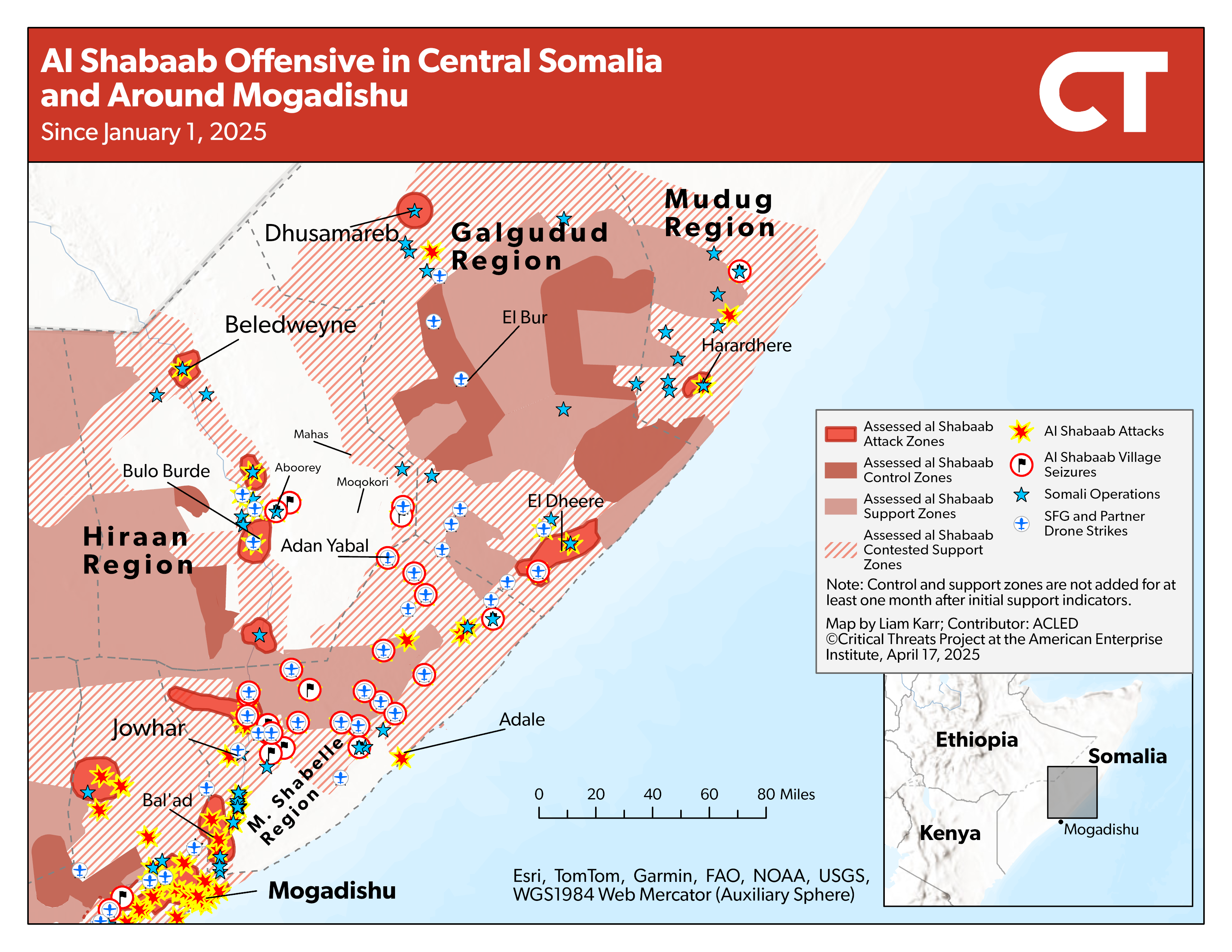

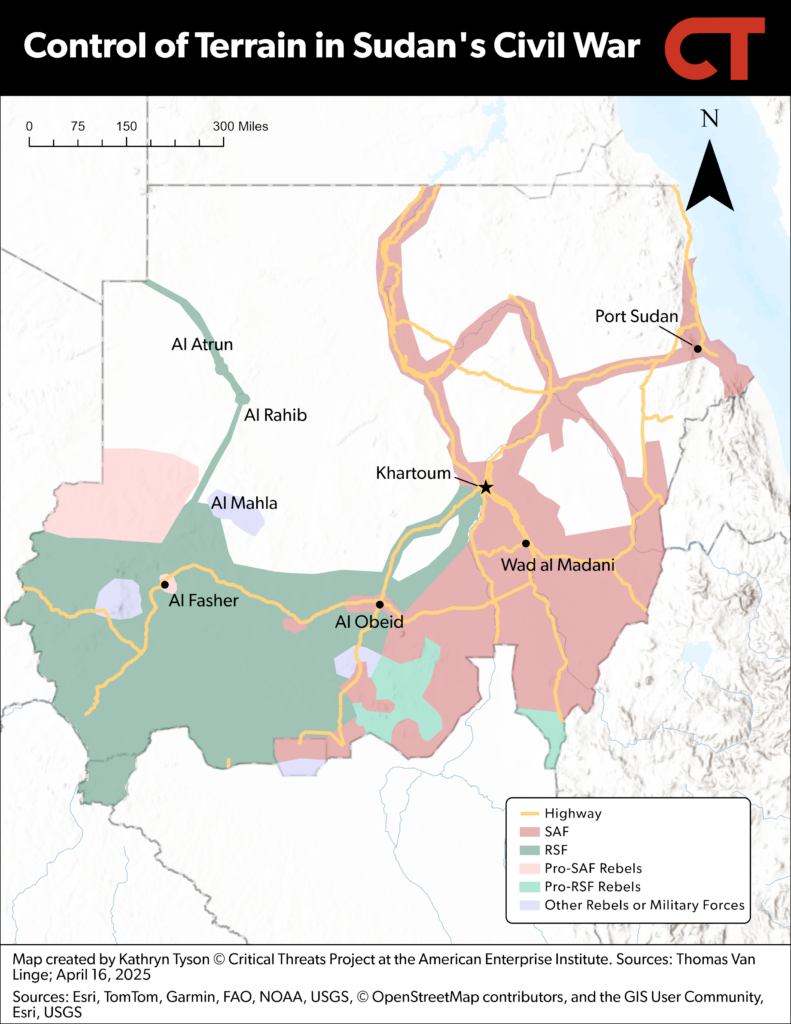

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has intensified their offensive against the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in western Sudan since losing Khartoum in March in order to consolidate control there and establish a de facto partition. The RSF attacked the Zamzam Refugee Camp—nine miles south of the North Darfur state capital al Fasher—on April 9 and captured the camp after days of fighting on April 13.[1] The last SAF military stronghold in the Darfur region is in al Fasher, and the RSF has besieged the state capital since April 2024.[2] The RSF has staged 400 vehicles at the Zamzam camp and is reportedly mobilizing more forces near al Fasher.[3]

The RSF has escalated an offensive to capture al Fasher since it lost Khartoum—the Sudanese capital—in March 2025. The RSF has captured other key SAF positions in Darfur to consolidate control over the lines of communication around al Fasher. The RSF attacked over 50 villages in Dar as Salam locality—around 29 miles south of al Fasher—as it tightened its siege on Zamzam Camp in March.[4] The RSF captured areas north of al Fasher, including the operationally significant town of al Mahla, in late March.[5] Several SAF-aligned armed groups were based in al Mahla.[6] The RSF on April 10 captured Umm Kadada, which is approximately 89 miles east of al Fasher along a key east-west highway and hosts an SAF infantry brigade that belongs to the same division stationed in al Fasher.[7]

Figure 1. Control of Terrain in Sudan’s Civil War

Source: Kathryn Tyson; Thomas van Linge.

The RSF has publicized its governance efforts in western Sudan to portray itself as a legitimate political power. The RSF published a video on March 26 of RSF fighters and tribal leaders “vowing to uphold security” to civilians in al Mahla in order to highlight the RSF as a legitimate protection force.[8] The RSF similarly released videos of RSF fighters “ensuring the security and protection” of civilians in Zamzam camp on April 14.[9]

The RSF has sought to consolidate control of western Sudan with its military campaign and its Darfur-based parallel government after losing Khartoum in March in order to effectively partition Sudan. The SAF launched an offensive to retake the divided capital in October and successfully cleared the RSF from central Khartoum in March. The development is a strategic setback to the RSF and its efforts to control the capital and present itself as a legitimate national power with more legitimacy than its historical reputation as the Janjaweed, the Darfur-based rebel groups that the RSF grew out of. The RSF officially launched a parallel government on April 16 after the SAF announced plans for a new SAF-led government in February 2025.[10] The RSF seeks to gain international support and legitimacy through the parallel government in order to mitigate the blow to its legitimacy that the loss of Khartoum represents.[11]

Figure 2. Area of SAF and RSF Operations in Darfur

Source: Kathryn Tyson; Thomas van Linge.

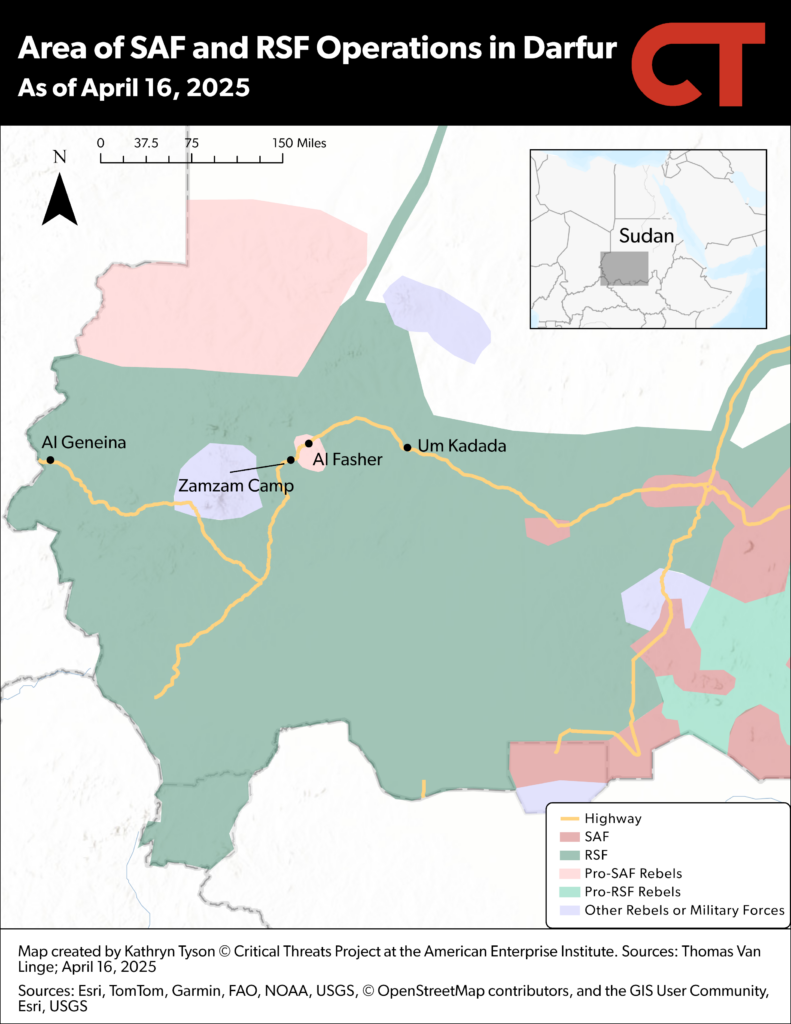

The RSF likely committed war crimes in its attack on the Zamzam camp. These actions are possibly constituent acts of ethnic cleansing or even genocide as defined under international law. The RSF killed over 300 civilians and displaced over 400,000 civilians in its offensive on the Zamzam camp and systematically destroyed homes, markets, and health care facilities.[12] The RSF deliberately executed ten staff members, including doctors and drivers, from the last organization providing critical services at the Zamzam camp.[13] The Yale Humanitarian Research Lab reported on April 14 that civilians around the Zamzam camp and al Fasher were “at imminent risk of torture, conflict-related sexual violence, and massacre.”[14] The RSF siege of al Fasher and deliberate attacks on humanitarian health workers had already imposed famine conditions on the Zamzam camp.[15]

The RSF’s actions around the Zamzam camp are possibly constituent acts of ethnic cleansing or even genocide as defined under international law. The Zamzam camp predominantly hosted Zaghawa and other non-Arab civilians that the Janjaweed displaced in the early 2000s Darfur genocide.[16] A UN Commission of Experts previously defined ethnic cleansing in the context of the conflict in the former Yugoslavia as “rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area” and “a purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas.”[17] Acts of ethnic cleansing may amount to constituent acts of genocide, which are defined as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group.”[18] The full scope of the attack around the Zamzam camp is unknown because the RSF has imposed a communications blackout.[19]

The RSF has likely committed multiple other war crimes around the Zamzam camp. The RSF likely violated international humanitarian law by deliberately attacking medical facilities, imposing famine conditions on the camp through its siege and targeting of humanitarian personnel, and executing unarmed people.[20] The brazen RSF attack on the camp likely violates the international legal principle of proportionality, regardless of the RSF’s claims that the SAF used the refugees in camp as human shields. Proportionality is a fundamental principle of humanitarian law that dictates that belligerent parties must take measures to minimize the cost to civilians and that civilian harm must not be disproportionate to the expected military advantage of conducting an attack or operation.[21] The SAF and SAF-aligned militias have disputed the RSF claims.

Figure 3. Instances of RSF Ethnically-Motivated Violence During the Sudanese Civil War

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

The attacks in al Fasher follow a pattern of the RSF abusing civilians throughout the civil war in ways that have been consistent with ethnically motivated violence, war crimes, and possible acts of genocide. The RSF conducted a “systematic” mass ethnic cleansing campaign against the Massalit ethnic group in al Geneina, West Darfur state, from April to November 2023, killing thousands, with upper estimates from the United Nations reaching 15,000 killed.[22] The RSF killed at least 300 civilians and displaced over 135,000 more between late October and early November 2024 in ethnically motivated attacks in Gezira state, central Sudan, after the SAF captured the Gezira state capital city of Wad Madani.[23] United Nations’ agencies have reported that both sides in Sudan, but primarily the RSF, has systematically used “rape and sexual violence as a weapon of war.”[24] Amnesty International reported in April that the RSF has committed “atrocities, including rape, gang-rape and sexual slavery” that amount to war crimes and possible crimes against humanity across Sudan in a deliberate effort to “humiliate, assert control and displace communities across the country.”[25] The RSF has increased attacks on civilian infrastructure in recent weeks, including several drone attacks targeting Merowe Dam in northern Sudan.[26] These attacks have caused widespread blackouts in major population centers, such as Khartoum, and the deliberate targeting of civilian infrastructure amounts to possible war crimes.[27]

The eventual RSF offensive on the city of al Fasher will likely lead to even greater ethnic cleansing and possible acts of genocide. RSF advances in recent weeks have set conditions to attack al Fasher, and the RSF is now staging at least 400 vehicles in the Zamzam camp for a likely offensive.[28] The United Nations and several international observers have warned that the RSF could conduct a genocide if it captures the Zamzam camp and al Fasher.[29] Hundreds of thousands of civilians fled from the Zamzam camp to al Fasher, which is now the last refuge for nearly 700,000 displaced civilians in the area.[30] The RSF has trapped these civilians and cut humanitarian assistance with its siege on the town.[31] The RSF has repeatedly demonstrated a pattern of ethnic cleansing in Darfur that includes acts of genocide stretching back to the Janjaweed’s 2000s Darfur—and as recently as ethnic cleansing and alleged genocide in al Geneina in 2023.[32] These examples serve as a template for what could happen if the RSF secures uncontested control over al Fasher.

Read CTP’s latest Africa File brief, “Sudan’s Civil War: Global Stakes, Local Costs.” The one-page brief covers the external actors fueling Sudan’s civil war, including Iran, Russia and the United Arab Emirates.

Somalia

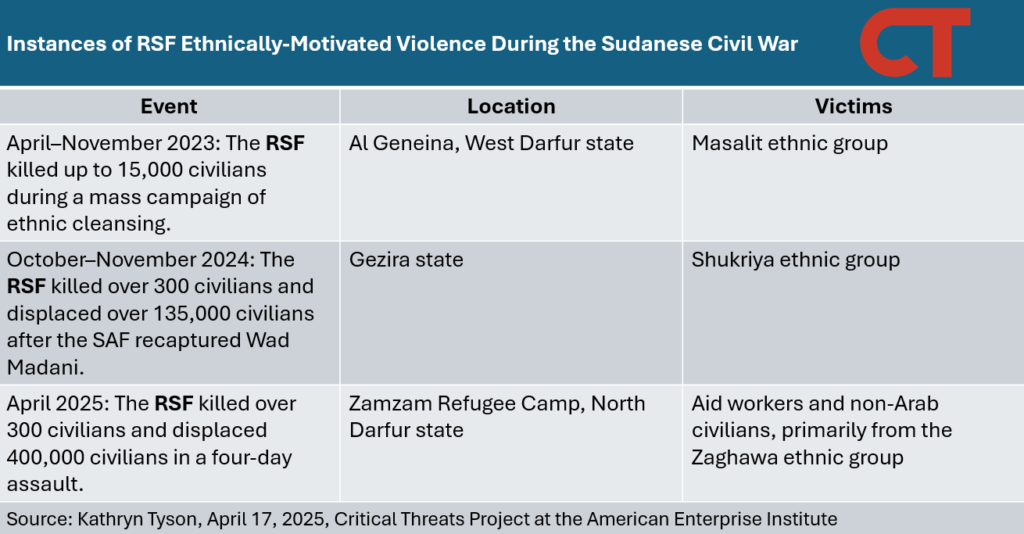

Al Shabaab captured two key areas in central Somalia that set conditions for the group to reestablish support zones there and connect them to its center of gravity in southern Somalia for the first time since 2022. Al Shabaab reinforcements crossed the Shabelle River in the Hiraan region in early April and captured Aboorey and Beero Yabal—two villages roughly 13 miles northeast and north of Bulo Burde town, respectively—on April 7.[33] Somali forces launched a counterattack on April 8 and retook part of Aboorey but withdrew from Aboorey and Yasooman—a mountainous locality five miles (10 kilometers) further east—on April 16, after over a week of fighting.[34] Al Shabaab launched a separate attack 42 miles (68 kilometers) southeast in Adan Yabal town, which is the easternmost district capital in the Middle Shabelle region, and captured the area after Somali forces withdrew.[35]

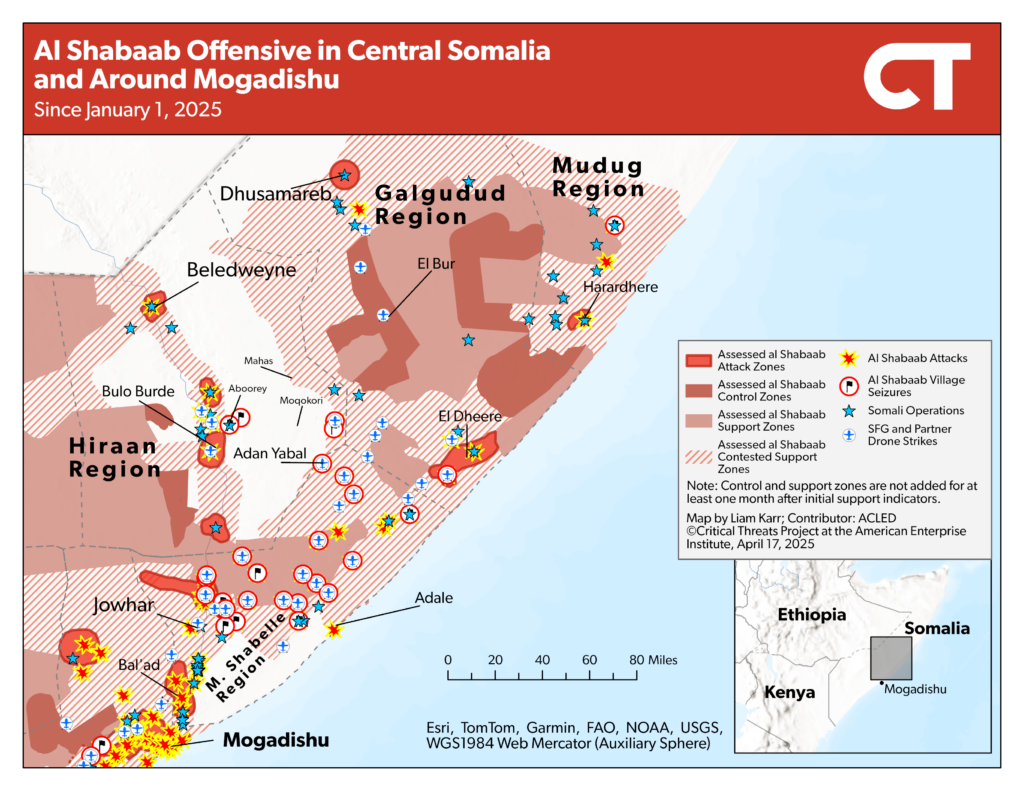

Figure 4. Al Shabaab Offensive in Central Somalia and Around Mogadishu

Note: Control and support zones are not added for at least one month after initial support indicators.

Source: Liam Karr, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Aboorey and Adan Yabal are two operationally critical areas of central Somalia. Al Shabaab has battled Somali forces repeatedly for control of Aboorey and the surrounding areas in several bloody battles since 2022 because the territory links al Shabaab’s support zones on the west side of the Shabelle River to other areas of central Somalia. Beero Yabal lies on the main north-south road between Mogadishu and the Hiraan regional capital, Beledweyne, and Aboorey is a gateway to al Shabaab-controlled areas of central Somalia farther northeast in the El Bur district in the Galgudud region. Somali forces’ initial efforts to clear these areas in 2022 resulted in hundreds of casualties, and Somali forces had already repelled two major al Shabaab offensives on Beero Yabal in early 2025.[36] Adan Yabal is a key crossroads town that links several regions in central Somalia and is nearly equidistant from several key villages, including al Shabaab-controlled El Baraf and El Bur and Somali Federal Government (SFG)–controlled Adale, Bulo Burde, El Dheere, and Mahas. Adan Yabal was al Shabaab’s administrative headquarters in central Somalia for over a decade before Somali forces captured the town in December 2022.[37]

Al Shabaab has waged an offensive in central Somalia throughout 2025, which aims to overpower Somali forces and reinfiltrate these areas, reconnecting the group’s territory in central Somalia with its center of gravity in southern Somalia.[38] Fighters from the group’s core territories in southern Somalia overwhelmed Somali forces in Bal’ad, Bulo Burde, and Jowhar districts while the group’s fighters in central Somalia targeted Somali forces further northwest in the Adan Yabal district.[39] Somali forces in 2022 launched an offensive that disrupted al Shabaab’s ground lines of communication between central and southern Somalia by clearing al Shabaab from the eastern halves of Hiraan and Middle Shabelle regions east of the Shabelle River.[40] These gains cut off al Shabaab’s central Somali forces.[41]

Al Shabaab already reestablished a support zone that links southern Somalia to central Somalia in March 2025. The two al Shabaab pincers from central and southern Somalia successfully reinfiltrated previously cleared areas of the Middle Shabelle region for the first time since 2022 and linked in the Adale district in March.[42] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) recorded only one al Shabaab–related event in Adale district in 2024 but since the beginning of March 2025 recorded 56 such events, including the capture of several villages.[43] These gains allowed the group to reinforce and resupply its forces in central Somalia.

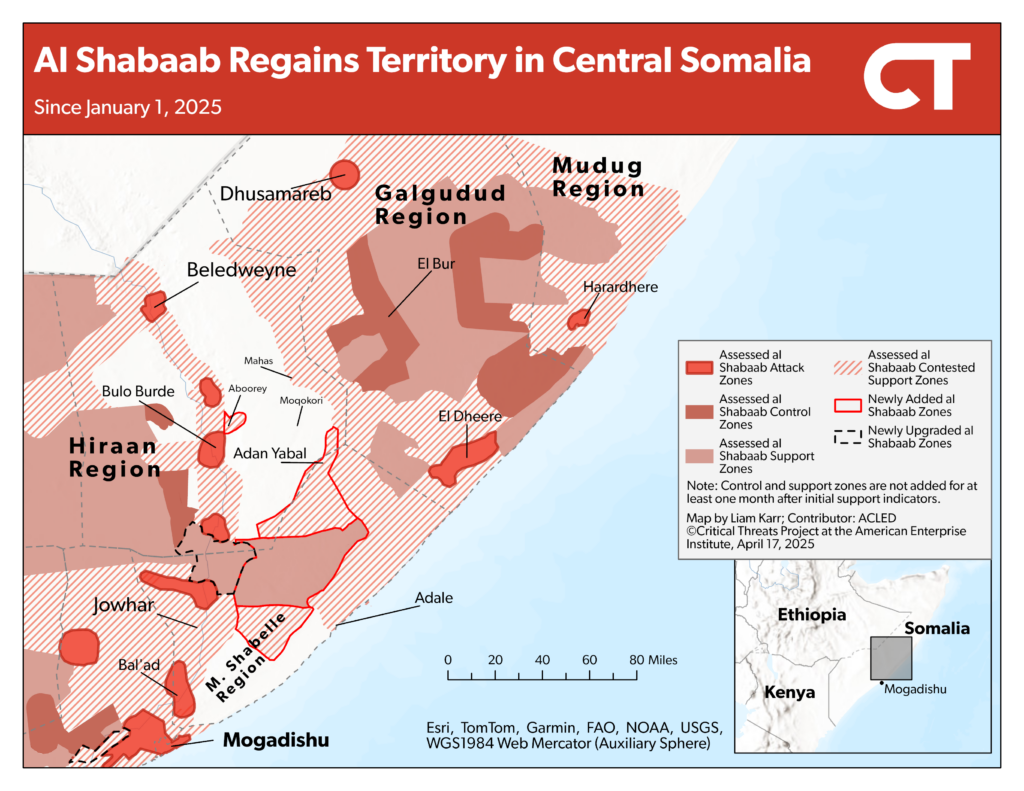

Figure 5. Al Shabaab Regains Territory in Central Somalia

Note: Control and support zones are not added for at least one month after initial support indicators.

Source: Liam Karr, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Al Shabaab is threatening to expand this support zone further to include multiple ground lines of communication and more directly connect with its central Somalia administrative hub, El Bur. Somali forces now only control two other towns in southeastern Hiraan region—Mahas and Moqokori. Al Shabaab forces are now within 45 miles of both towns from each of the east, south, and west. Al Shabaab control of these towns would provide a buffer that protects the group’s ground lines of communication in Middle Shabelle and would establish support zones along additional ground lines of communication between El Bur, Middle Shabelle, and al Shabaab’s support zones west of the Shabelle River in southern Somalia.

Somali forces have performed poorly in some areas, and the scope of al Shabaab’s offensive has overwhelmed Somalia’s international partner-provided air support. Thousands of Somali forces fled from a much smaller al Shabaab force at Adan Yabal.[44] Lingering clan grievances, underprepared Somali forces taking over from African Union (AU) forces, and al Shabaab’s remaining support zones in central Somalia have all likely contributed to al Shabaab’s recent gains.[45] Somali officials claim that decreased air support contributed to al Shabaab’s capture of Aboorey.[46] ACLED recorded six drone strikes in the Bulo Burde district in 2025 but none since March 23, before the latest round of fighting around Aboorey.[47] This decrease is likely because international partners are preoccupied trying to contain the al Shabaab incursion in Middle Shabelle and around Adan Yabal. International partners conducted 30 drone strikes in Middle Shabelle between January and March 13 and have conducted a further 20 drone strikes over the following month.[48] These strikes have not denied al Shabaab’s ability to rotate its forces from central Somalia or to stage the attack to recapture Adan Yabal, despite killing hundreds of militants.

Al Shabaab’s growing gains in central Somalia threaten to inflict a strategic setback on the SFG by undoing the US-backed Somali counterterrorism offensive in 2022. Al Shabaab’s gains will allow the group to increase pressure on the main highway that runs along the Shabelle River from Mogadishu through Middle Shabelle and Hiraan. Somali forces had cleared the highway and created a buffer zone on the eastern side of the road during the 2022 offensive. Al Shabaab’s capture of Adan Yabal puts significant pressure on the remaining SFG-controlled areas in the Middle Shabelle region and neighboring Galgudud region. Al Shabaab had historically used Adan Yabal as a staging ground and vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (VBIED) manufacturing hub.[49] The roads that run from the town allow al Shabaab to threaten the SFG-controlled district capital El Dheere and several points along the road that runs from El Dheere toward Mogadishu via Middle Shabelle. Al Shabaab’s reinvigorated presence in central Somalia will pose a greater threat to the SFG-controlled district capital Harardhere, which is on the northern flank of al Shabaab’s central Somalia territory in the Mudug region. Adan Yabal, El Dheere, and Harardhere were the three district capitals that Somali forces captured from al Shabaab in 2022.

These losses would undermine the SFG’s domestic and international credibility in its ability to eventually retake its national territory from al Shabaab. Many of Somalia’s international partners praised the 2022 offensive as the first Somali-led counterterrorism offensive to retake significant territory from al Shabaab.[50] The offensive boosted morale within Somalia and led the SFG to try to replicate the offensive in other parts of the country and tout plans to take over more security responsibilities from international forces.[51] The offensive stalled in 2023, however, and the SFG’s clan-based coalition began to collapse in 2024, as the SFG was distracted with other domestic and regional political issues.[52] The offensive benefited from al Shabaab’s missteps that alienated locals in the area, the Somali president’s clan ties in the area, and the prevalence of strong clan militias in the area.[53] The SFG was unable to consolidate its gains despite these favorable conditions, which are not present in al Shabaab’s center of gravity in southern Somalia.

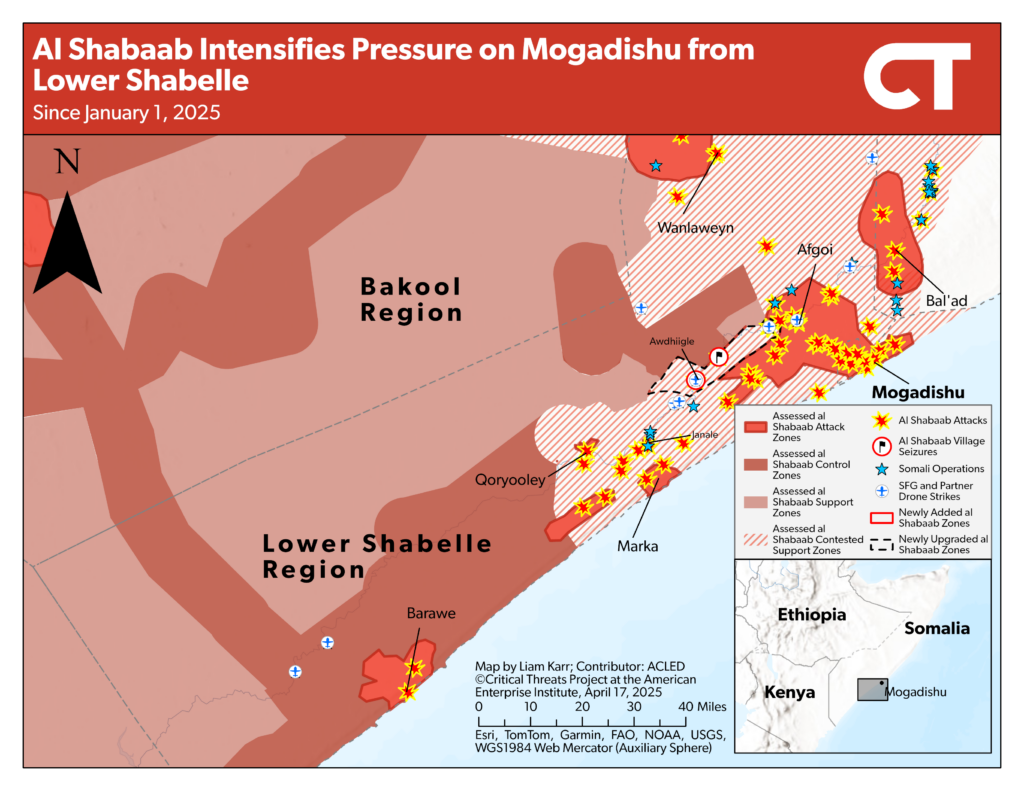

Al Shabaab opened a second front south of Mogadishu in March and has captured several operationally key towns. Al Shabaab captured Awdhiigle, Bariire, and Saabid in the Lower Shabelle region in late March 2025, although Somali forces recaptured Saabid.[54] These towns are all crucial for Somali forces to defend Mogadishu from al Shabaab VBIEDs.[55] All the towns are in the Afgoi district—effectively the Mogadishu suburbs, within 30 miles of the Mogadishu administrative limits—along one of the two main roads that lead to Mogadishu via Afgoi town. These towns have key bridges over the Shabelle River that link the al Shabaab–controlled areas of southern Somalia to the main road and, therefore, Mogadishu.[56]

Al Shabaab likely pushed an information operation highlighting the group’s activity along the stretch of the road between Afgoi town and Mogadishu to raise further alarm in Mogadishu. Al Shabaab–affiliated media amplified reports of al Shabaab patrols along the road in the Mogadishu outskirts in late March.[57] The group has been attacking Somali forces in this area for years and has not sustained these patrols, however.[58]

Figure 6. Al Shabaab Intensifies Pressure on Mogadishu from Lower Shabelle

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Al Shabaab is highly unlikely to launch an offensive on Mogadishu to seize power in the short term, but its gains in central and southern Somalia will allow the group to destabilize Mogadishu and undermine the legitimacy of the SFG. The areas around Mogadishu could serve as staging grounds for a conventional assault on Mogadishu. A conventional offensive on Mogadishu would be very risky and would take substantial preparation, however, especially given that the group will need to reconstitute some of its forces after its current offensive. Somalia’s international partners would pose a significant threat to al Shabaab’s chances of success. Emirati, Turkish, and US drone strikes would be able to target large gatherings of al Shabaab militants. Somalia’s regional partners in the AU peacekeeping mission—Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda—have thousands of troops in Somalia and no interest in the spike in regional instability that would occur if Mogadishu fell to al Shabaab.[59] Al Shabaab has attacked all these countries directly, and these partners have intervened in the past when Mogadishu is under threat.[60] Al Shabaab has not attempted a conventional assault to capture Mogadishu since regional AU forces pushed the group out of Mogadishu in 2011 for many of these same reasons.[61]

Al Shabaab’s gains will likely enable the group to launch more high-visibility attacks in Mogadishu that highlight the SFG’s inability to provide security. Al Shabaab can use its presence along key points on the highways in central and southern Somalia to stage and move suicide commandos and VBIEDs into the capital. The group conducted at least nine attacks that used VBIEDs in Mogadishu over 13 months between August 2022 and September 2023 in response to the SFG-backed central Somalia offensive but has only conducted four VBIED attacks since the SFG campaign subsided toward the end of 2023.[62] The group could also try to target more politically sensitive areas of Mogadishu. Al Shabaab has conducted other high-visibility attacks in Mogadishu targeting the embassy compound at the Mogadishu airport and Villa Somalia since March 2025.[63] Al Shabaab regularly conducts these kinds of symbolic attacks, however, and the rate of attacks in the most politically sensitive districts that contain Villa Somalia and the embassy compound is down overall by over 80 percent in 2025 compared to 2024.[64]

Al Shabaab can use areas surrounding Mogadishu to bolster its own shadow governance activities and pressure Mogadishu’s economy, both of which would undermine the SFG’s legitimacy. Al Shabaab bases courts, officials, and other administrative systems overseeing Mogadishu in the Mogadishu district outskirts or suburbs in Afgoi district.[65] Control of the roads in central and southern Somalia surrounding Mogadishu would create opportunities for the group to improve its legitimacy vis-à-vis the SFG by exerting pressure on traffic in and out of Mogadishu. Al Shabaab could boost its own legitimacy by taxing traffic as it does in other areas of Somalia, or the group could decrease the SFG’s legitimacy by using “siege” tactics to disrupt the local and national economy.[66] Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has used such tactics on a smaller scale to cause local governments to collapse under economic and food supply pressure.[67]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

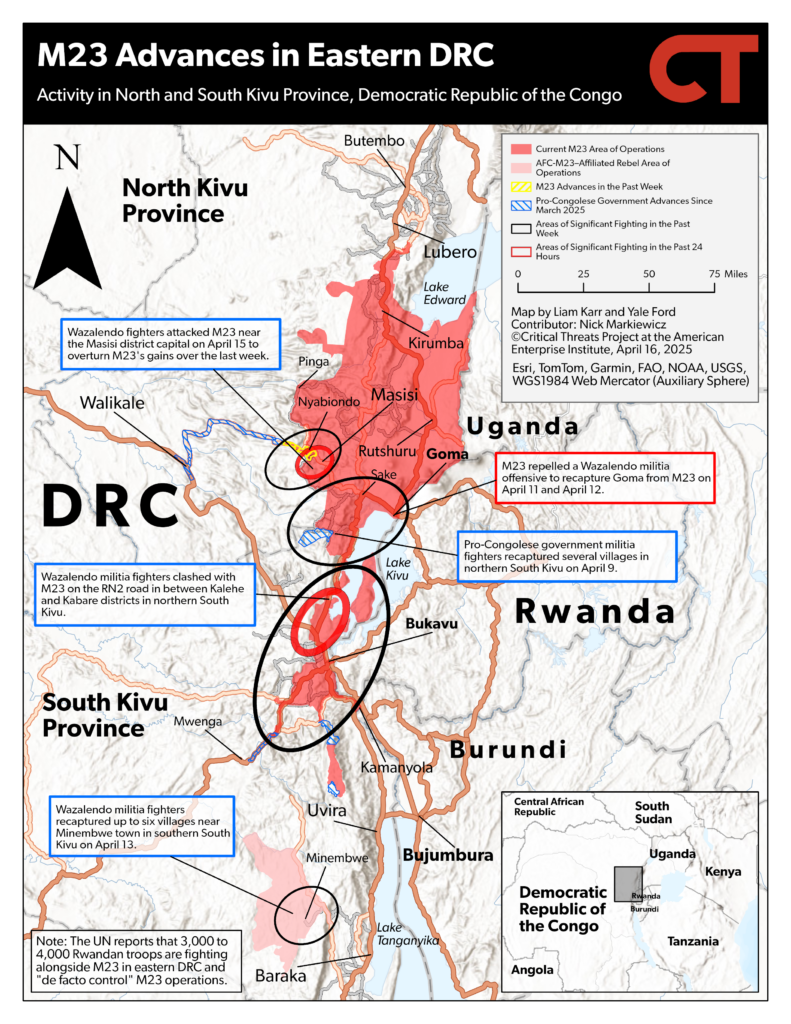

Pro-Congolese government Wazalendo fighters launched offensives on positions near the North Kivu and South Kivu provincial capitals, Bukavu and Goma, respectively. Wazalendo fighters launched an offensive on April 9 that captured several villages in Kalehe district near the South Kivu border with North Kivu and up to a dozen villages on the RN2 road in South Kivu’s Kabare district.[68] M23 began sending reinforcements “en masse” to Kabare district from North Kivu, Bukavu, and the Kavumu airport—roughly 20 miles north of Bukavu—to reassert control over the RN2, but Wazalendo fighters have continued to contest the area.[69]

A significant number of Wazalendo militia fighters launched “well-coordinated” attacks against M23 in the western part of Goma and on Goma’s outskirts on April 11 and April 12 in order to retake the North Kivu provincial capital.[70] M23 repelled the Wazalendo attacks and claimed that Congolese army (FARDC) soldiers, Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops, and fighters from —an ethnic Hutu militia with links to the Rwandan genocide—participated in the attack on Goma.[71] The FARDC and the SADC denied their involvement in the attacks on Goma.[72]

Figure 7. M23 Advances in Eastern DRC

Source: Yale Ford and Liam Karr.

The Wazalendo offensive is the latest sign that M23 continues to face capacity and supply challenges that limit its ability to consolidate military control over its area of operations. M23 has been unable to fully secure several district capitals in North Kivu, along with Goma, in recent weeks. These struggles signal that the group is likely overstretched. FARDC and allied Wazalendo militias recaptured Walikale town from M23 on April 3 after the pro-Congolese forces flanked M23 and cut the group’s ground lines of communication between Walikale and the Masisi district capital.[73] M23 forces retreated from Walikale back toward Masisi and have been unable to maintain a solid defensive perimeter around Masisi town and clear Wazalendo fighters from the surrounding villages.[74]

Recent Wazalendo attacks have separately exposed M23’s porous front lines around Bukavu. Wazalendo militias have attacked towns within 15 miles of Bukavu regularly and even Bukavu directly on March 3.[75] Burundian troops and Wazalendo fighters recaptured an area south of Bukavu in northern Uvira district in mid-March after M23 faced severe supply shortages.[76] FARDC and Wazalendo fighters reportedly recaptured Nyangezi village—about 15 miles south of Bukavu on the RN5 road—on April 1, thereby severing M23’s ground lines of communication between Bukavu and M23-controlled Kamanyola, the southernmost Congolese town along the DRC-Rwanda border.[77] Wazalendo fighters briefly occupied the Kavumu airport on April 13 after M23 redeployed troops from Kavumu to support its operations on the RN2 near Katana.[78]

These military challenges have coincided with M23’s continued struggles to effectively govern Goma and Bukavu and implement its broader political agenda across North Kivu and South Kivu. Both Goma and Bukavu and their peripheral areas have faced persistent insecurity since M23 captured the two provincial capitals in late January and mid-February, respectively.[79] An unidentified attacker detonated explosives in an assassination attempt on senior M23 officials and Corneille Nangaa—the leader of M23’s political branch, Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC)—during a public rally in Bukavu in late February.[80] M23 has lacked the law enforcement personnel to fully secure Bukavu and Goma, and the rebel group has forcibly conscripted young people and sought to absorb FARDC and local police units in both cities to address spikes in homicide, looting, and other crime. [81]

Goma and Bukavu have faced cash shortages and rising prices that have caused significant economic difficulties for residents. The Congolese government has prohibited financial institutions tied to the DRC’s central banking system in Kinshasa—the DRC capital—from operating in M23-occupied areas.[82] M23 has appointed finance officials and launched a parallel banking system in areas it controls to attempt to circumvent Kinshasa’s injunction and ease the liquidity crunch.[83] The Congolese media outlet Kivu Morning Post quoted a “local official close to M23” on April 7 who said that the initiative is mainly a “political act aimed at reassuring residents and economic operators.”[84] M23’s efforts to establish a parallel financial system will likely face challenges, however, because of international restrictions on money laundering and the parallel system’s limited connections to correspondent banks.[85]

M23 has taken steps to solidify its administrative control over areas that it occupies through the appointment of M23 loyalists to political positions. M23 has announced numerous high and mid-level appointments to run M23-held areas since it captured Goma in late January, including “governors” of North Kivu and South Kivu provinces and district administrators for several districts in the two provinces.[86] M23 installed its own police and customary authorities at the local level, conducted “household identification and census operations,” and forced residents to do salongo, a local practice of communal labor.[87]

The Wazalendo attacks likely aim to taint M23’s legitimacy as a capable governing force and weaken M23’s bargaining power in direct peace talks with the DRC government. The highly visible Wazalendo offensive highlights the M23’s military vulnerabilities, which undercut M23’s negotiating leverage in Qatar-mediated peace talks. An analyst for the International Crisis Group characterized the Wazalendo attacks on Goma to French state media as a “harassment strategy coupled with a communications operation” aimed at undermining M23.[88] Economic instability and persistent insecurity around Goma and Bukavu undermine M23’s public image as a stabilizing force that can govern and provide security and opportunity to large population centers better than the DRC government, which M23 denounces as “corrupt” and “incompetent.”

Wazalendo militias will likely continue to be a challenge to peace efforts in the immediate and long term. The Wazalendo fighters are formally allied to the Congolese army by law but are not a party to the unconditional ceasefire between the DRC and Rwanda brokered by Qatar in mid-March or subsequent Qatari-mediated efforts between the DRC and M23.[89] A Wazalendo militia leader said in an interview with Congolese media in mid-April that Wazalendo fighters “do not agree on the discussions taking place in Doha” and that “what [DRC President Félix Tshisekedi] does with the [M23] rebels does not concern us, the Wazalendo, if he wants to talk with Rwanda.”[90] “A Congolese politician in the DRC’s National Assembly from the Walikale district attempted to declare a ceasefire on behalf of Wazalendo fighters in connection to the Doha talks in mid-April, but the fighters rejected the call and said they would keep fighting.”[91] Previous ceasefires between the DRC and Rwanda led to a drop in overall violence in the eastern DRC but failed to limit direct hostilities between M23 and Wazalendo fighters.[92]

FARDC’s ability to control Wazalendo and other anti-Rwanda militias will be a long-term obstacle to peace negotiations and any efforts to implement a peace deal in the eastern DRC. Both M23 and Rwanda—M23’s primary patron—have demanded that FARDC break their alliance with and target Wazalendo and FDLR-linked militants as part of any long-term peace agreement.[93] M23 has conducted operations against suspected FDLR fighters north of Goma in the Virunga National Park and southern Rutshuru district since late March.[94] The FARDC has faced long-standing difficulties in constraining, demobilizing, or integrating militia fighters into the ranks of FARDC.[95] Domestic and international efforts to demobilize and reintegrate Mai-Mai militias, which were the predecessor to the Wazalendo militias, failed and led to persistent violence in the eastern DRC in the decades after the Second Congo War.[96] The UN reported in December 2024 that FDLR fighters are embedded into pro-Congolese government militia units and that the DRC government “continued to systematically rely on and cooperate with [pro-Congolese government militias] and FDLR.”[97] The United Nations reported in April 2025 that FDLR “intensified its collaboration” with Wazalendo militia groups allied to the FARDC.[98]

Sahel

The latest diplomatic row between Algeria and Mali could strain Algeria’s relations with Mali’s Nigerien and Russian partners. Algeria downed a Malian drone near the Algeria-Mali border town of Tinzaouten on April 1 after Algerian officials claimed that the drone crossed into Algerian airspace.[99] The drone was one of Mali’s two Turkish-made Bayraktar Akinci drones—a higher-end drone than the more common Bayraktar TB2.[100] Mali retaliated by withdrawing its ambassador, summoning the Algerian ambassador, and announcing that it would “reinforce” its position along the Algerian border, where it controls none of the mostly desert territory.[101] Mali’s allies in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES)—Burkina Faso and Niger—also withdrew their ambassadors from Algeria.[102] Algeria responded by withdrawing its ambassador from Mali and Niger, delaying the appointment of an ambassador to Burkina Faso, and closing its airspace to Malian aircraft.[103]

Algeria and Mali’s relationship had already significantly deteriorated since 2024, when the Malian junta escalated military activity against separatist Tuareg rebels in northern Mali near the border with Algeria.[104] This offensive ended a 2015 Algerian-brokered peace deal, which Algeria still strongly supported and tried to salvage in December 2023 due to fears that renewed hostilities in Mali would mobilize the Tuareg population in Algeria and cause refugees to flee into Algeria.[105] One of the biggest engagements of the 2024 offensive occurred near Tinzaouten in July, when Tuareg militants with likely ties to both Tuareg rebel groups and al Qaeda affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen killed up to 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers in an ambush.[106] Algeria had previously taken other military measures to deter Malian overreach along their shared border, such as live-ammunition military drills on the border.[107]

Figure 8. Malian and Russian Forces Battle Tuareg Insurgents in Northern Mali

Source: Liam Karr, Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.

Niger’s involvement in the dispute will test the cohesion of the AES, as the issue places Niger in a tough spot between the AES and its partnership with Algeria. Algerian mediation efforts in Niger in the immediate aftermath of the 2023 Niger coup failed.[108] Algeria’s forceful anti-immigration policy raised tensions with the Nigerien junta further in early 2024, which has scaled back anti-immigration efforts to capitalize on the illicit trans-Saharan migration economy.[109] Algeria and Niger began to repair their relationship in the second half of 2024, however. The two countries resumed discussions on the trans-Saharan gas pipeline that intends to link Nigerian oil to Europe via Algeria and Niger.[110] Algeria, Niger, and Nigeria signed a series of deals to advance the pipeline project as recently as February 2025.[111] Algeria discussed in 2025 plans to help Niger build an oil refinery, petrochemical complex, and a 40-megawatt power station.[112]

Algeria and Niger both benefit from their partnership, and their efforts to navigate the ongoing dispute will test the cohesion and effectiveness of the AES as an international political bloc. Algeria seeks to offset the regional impact of its strained relationship with Mali as Algeria competes with its main rival—Morocco—for influence in the Sahel.[113] Niger seeks investment to stabilize its fragile economy.[114] Algeria’s move to ban only Malian aircraft from its airspace signals that it wants to compartmentalize the dispute to just Mali.[115] Niger has followed its AES partners by withdrawing its ambassador, but Niger has not been put in a position to take any further direct retaliatory measures.[116]

The dispute will likely strain Algeria and Russia’s historically strong relationship. Algeria has increased ties with the West in recent years, likely to balance its relationships, partially due to Russia’s destabilizing activity around Algeria. The growing tensions between Algeria and the Russian-backed AES have likely strained the historically strong Algerian-Russian partnership. Algeria has maintained a close relationship with Russia that includes significant defense ties and cooperation in international institutions that dates back to the Soviet Union and has persisted after Russia invaded Ukraine in March 2022.[117] The Kremlin sent five Su-35 jets to Algeria in March, and Algeria will receive Su-57 stealth fighter jets in 2025.[118] Algeria has appealed to Moscow to help decrease tensions in the Sahel repeatedly, but Russia has shown itself to be unable or unwilling to rein in the Malian junta.[119] Russian forces have enabled Mali’s offensives in northern Mali, and the Kremlin has increased arms shipments to Mali in 2025.[120] Algeria has signaled increasingly—publicly and privately—that it views Russia’s activity in the Sahel and neighboring Libya as a threat to Algerian and regional stability.[121]

Algeria has sought greater cooperation with Europe and the United States directly and indirectly in reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Russia’s destabilizing activity around Algeria in Africa. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led Algeria to emerge as an alternative energy supplier for European countries seeking to shift away from Russian gas and highlighted Algeria’s overreliance on Russian arms supplies.[122] Algerian and US military engagement reached a new peak in early 2025 after the two countries signed a wide-reaching memorandum of understanding and elevated discussions between top military leaders.[123]

add note

tweet