Fighting alongside Malian soldiers, Wagner mercenaries have massacred civilians and burned their villages in northern Mali, fueling a fast-growing refugee crisis.

Families travel through the night on desert backroads, arriving in this desolate borderland each day with new stories of terror about the White men in masks who drove them from their homes.

Mercenaries with Russia’s Wagner Group, fighting alongside Malian soldiers, have assaulted women, massacred civilians and burned villages in Mali, the displaced say — a campaign of wanton violence that is fueling a rapidly growing refugee crisis to the west in neighboring Mauritania.

“We have never seen anything like this,” said Kossi ag Mohamed, a 31-year-old herder who described fleeing his village in Mali’s Timbuktu region. Wagner, he said, had brought “catastrophe.”

Mali’s military junta, which seized power from the democratically elected president in a coup d’état in 2020, began working with Wagner in late 2021. Nearly two years later, the future of the Kremlin-linked mercenary group was thrown into doubt when its founder, Yevgeniy Prigozhin, was killed in a plane crash after a short-lived rebellion against President Vladimir Putin.

But Wagner never went away, and its fighters have continued to deploy overseas — a shadow force that experts say now operates as an extension of Russia’s Defense Ministry. In Mali, the group’s footprint has only grown, according to analysts and visuals verified by The Washington Post, providing a revenue stream for Putin’s cash-strapped government and a base of influence for Moscow in an increasingly anarchic West Africa.

Malian authorities say the partnership is designed to combat Tuareg separatists — who have long agitated for their own state in northern Mali — as well as militant groups loyal to al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. But it is civilians, not armed groups, that have borne the brunt of Wagner’s brutality.

“They kill people very indiscriminately,” said Héni Nsaibia, West Africa senior analyst for the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, or ACLED, a nonprofit research group. “They see a convoy of transport vehicles or people doing business, and they attack. They kill men, women and children. Then they loot the goods.”

Russia’s Defense Ministry, Wagner and the Malian government did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

In recent months, Ag Mohamed said, the men in his area had developed a grim ritual: hiding in the trees when they heard a military convoy approaching, and then, when it was safe, following the gunshots they had heard to collect the dead.

His eyes were blank as he scrolled through videos he said he and his friends had taken. One showed seven bloodied corpses sprawled on the ground. In another was a decapitated man, his head placed between his hands. The bodies of women and children were visible in a third video, lying in the ashes of a burned home.

“It is death that made me flee,” Ag Mohamed said. “I saw death everywhere.”

A policy of terror

When Mali’s junta extended the invitation to Wagner — it always said its contract was with the Russian state, not the Kremlin-linked mercenary group — violence by Islamist extremists was on the rise. One of Wagner’s goals, an operative recounted in a recent interview, was helping the army take back bases and territory that had fallen under the control of extremists.

The Malian government pays about $10 million a month for Wagner’s services, analysts say, a boon to Moscow as it weathers international sanctions over its war in Ukraine. Russia has also been awarded concessions at several gold mines, giving the country a material stake in Mali’s security.

Although Malian forces have made some gains since the arrival of the Russian mercenaries, now believed to number around 1,500, experts say military operations in areas beyond state control have been characterized by overwhelming brutality.

“It’s a policy of ‘kill them all,’” said Wassim Nasr, a Sahel specialist and senior research fellow at the Soufan Center. “They are trying to terrorize the local population.”

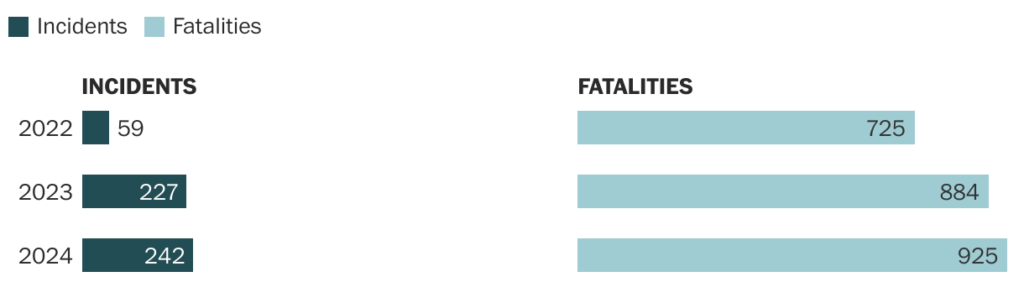

ACLED estimates that at least 925 civilians were killed last year in attacks involving Wagner — more than double the 400 civilians the group estimates were killed by Islamist militants.

Andrew Lebovich, a research fellow with the Clingendael Institute in the Netherlands, said that Mali’s military has long been accused of human right violations but that the scale and ferocity of abuses have increased since Wagner entered the picture.

The mercenaries have adopted “dirty-war tactics,” Lebovich said, including kidnapping, torture and decapitation. Multiple refugees told The Post that corpses were often mutilated before the army withdrew.

Desperate flight

Even before the crush of new arrivals, the Mbera refugee camp in Mauritania’s southeastern desert had become the third-largest population center in the country.

Tens of thousands of Malians arrived here in 2012, when extremists and separatists overran much of their country, and the camp continued to grow over the next decade as Mali lurched from one crisis to the next. But the exodus last year was unprecedented; there are now some 149,000 people in and around Mbera — triple the number in 2023, according to the United Nations. The camp itself is long past capacity and sprawls in every direction.

In more than two dozen interviews, refugees who have arrived since 2023 said it was attacks by Mali’s military and its Russian allies — not Islamist militants — that made them flee. Al-Qaeda’s regional affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, or JNIM, controls large amounts of territory in Mali and competes for influence with a local branch of the Islamic State, which is smaller but more brutal.

Some refugees said that they had experienced intimidation years ago from extremists who sought to impose their rule but that village life had largely returned to normal before the army came.

“They consider everyone who wears a turban a terrorist,” said 45-year-old Cherfe ag Mama, who said his brother was killed by Wagner mercenaries in the Timbuktu region.

A women’s leader in the camp, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive subject, described a whisper network of women who have shared stories of sexual assault committed by Wagner operatives.

Aïssata Kelli, a 40-year-old mother of two, recounted the moment gunmen burst into her home in November. She was too terrified to look at them for long, but she said she saw they were White, wore masks and shouted a version of the same two questions, again and again.

“Where are the jihadists?” Kelli remembered the men yelling in French at her and a few other women nearby. “Where are your husbands?”

Most of the men in their village, including Kelli’s husband, had fled when they heard the military was en route. Kelli told the men that her husband was not a jihadist and that she did not know where he was. The White men screamed and hit her as they stripped off her clothes, she recalled, searching for a phone they thought she was hiding.

“I am even scared at the memory,” said Kelli, as she sat beside her husband, a partly blind herder, in their recently erected tent. “I thought they were going to kill me.”

The attack on their village lasted for three agonizing days, according to Kelli and her friend, 35-year-old Siray Bah. Wagner mercenaries and Malian soldiers ransacked homes and businesses, the women said, then set them on fire.

Five men, including the village imam, were killed, and several others were kidnapped. Among them was Bah’s husband, father to her seven children, taken by gunmen from the market where he had gone to buy food for the family.

Bah, nursing her newborn baby, said she called his phone repeatedly in the days after he disappeared. No one ever answered.

Russia’s growing presence

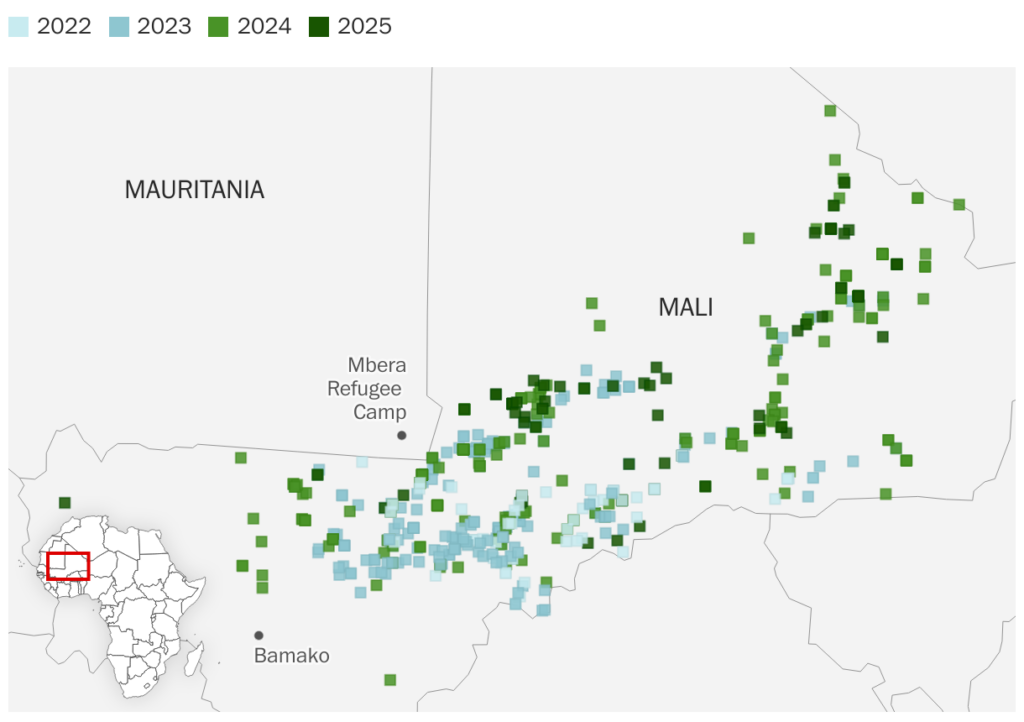

While Wagner’s initial focus was on central Mali, analysts say, the group has increasingly expanded its operations into the north — the epicenter of a long-running fight between the state and ethnic Tuareg rebels, who have fought for decades to establish an independent state.

One of Wagner’s most significant victories in Mali was taking back the historic rebel stronghold of Kidal in 2023; the group suffered its largest setback last summer, losing dozens of men in a battle with Tuareg fighters near the Algerian border.

Analysts said the losses were controversial in Russia, and prompted questions about the future of the group in Africa. But in recent months, there has been a spike in military equipment coming from Russia into Mali, according to analysts and visuals.

Jennifer Jun, an associate fellow for imagery analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said satellite images show signs of recent expansion at a military base at Bamako’s Modibo Keita International Airport, where Wagner has been known to operate since 2021.

There have also been more recruitment efforts by Wagner, and more chatter on social media from the mercenaries themselves.

“Mali was really a black box,” said Lou Osborn, the founder of All Eyes on Wagner, a nonprofit that investigates the mercenary group. “The images we saw of Wagner in the country were not from Russians. Now Russians are communicating.”

In a video published on Telegram in December, two veterans of the Wagner Group — Alexander Kuznetsov, known by the nom de guerre “Ratibor,” and Ruslan Zaprudsky, or “Rusich” — drive through a crowded street in Bamako, Mali’s capital, with their faces unmasked and un-blurred.

On Feb. 16, a Wagner-affiliated Telegram account posted photos of a fire blazing near Kidal, with a caption that says the town “has undergone a slight transformation.” Planet Labs satellite imagery between Feb. 15 and 17 shows a burn scar almost two miles long running beside the village.

Analysts said the location of the fire on the edge of a community suggests a strategy of intimidation, likely intended to force people out.

Nowhere is safe

In most places, the border between Mali and Mauritania is no more than a line in the sand.

When Wagner is conducting an operation, the displaced cross the border throughout the day, said Ibrahim Sidi Mohamed, the local leader in Douankara, a once-sleepy village on the Mauritanian side, about 30 miles from Mbera.

The number of families living in Douankara has exploded since 2023, from 380 to 4,020, he said. They come in pickup trucks, bringing only the things they can carry. The lucky ones have room for their livestock.

People live in tents, or in one-room structures they’ve cobbled together from wood and tin. Even for those who make it to the village, there is no promise of safety.

Ould Bacana, a 30-year-old refugee who had been living in Douankara, was killed by a Wagner patrol three miles from the village, according to Mohamed and Bacana’s mother.

Bacana, the family breadwinner, had been on his way to sell goods at a cattle market just across the border in Mali when he and a handful of other men were killed by Russian mercenaries, witnesses later told Mohamed. Locals found the bodies and buried them in shallow graves covered with branches and twigs.

“It is only women that are left — they have killed all the men,” Bacana’s mother, Izi Sidi Ahmed, said as she sat curled in her tent. The tiny woman nodded at her teenage son, saying she did not let him venture across the border, even though the family now has little to eat.

“What are we supposed to do?” she asked, repeating the question as if to herself.

“What are we supposed to do?”