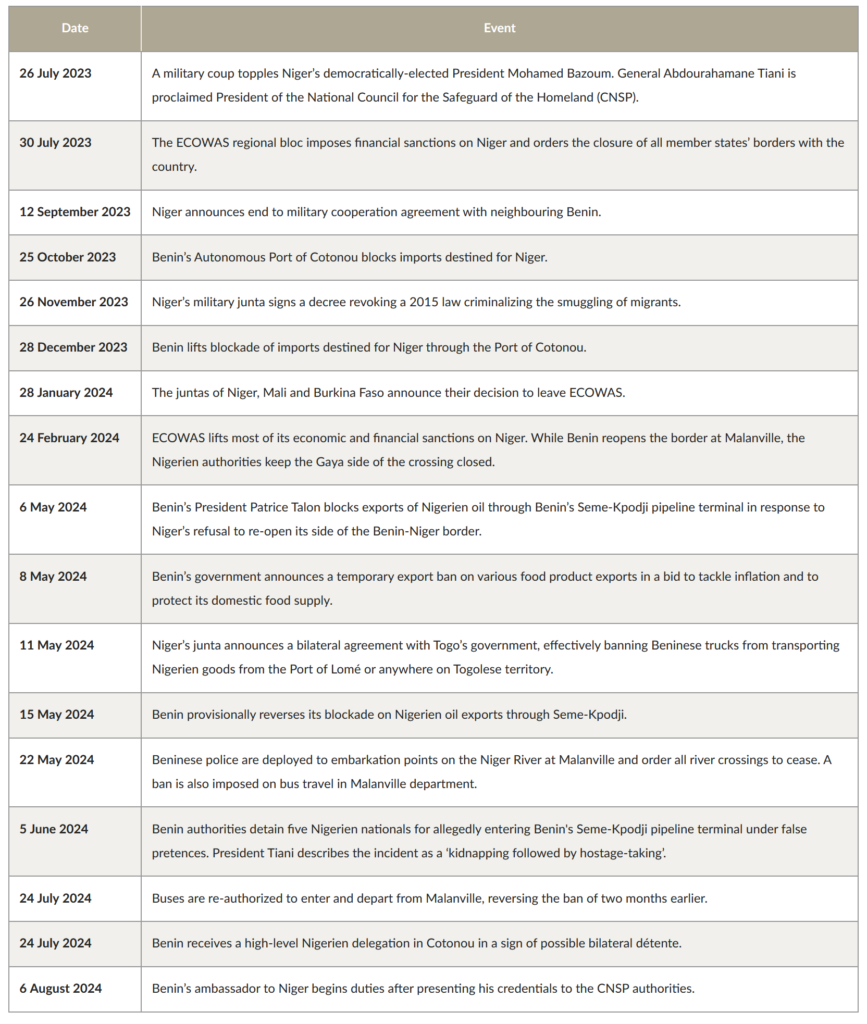

When Niger’s democratically elected President Mohamed Bazoum was overthrown in a July 2023 coup, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) moved within days to impose punitive measures that it hoped would force a return to constitutional order. This included financial sanctions on Niger and the closure of all member states’ borders with the country.1 The bridge over the Niger River, linking the Beninese city of Malanville and the city of Gaya in Niger – a key transit point for migrants and both licit and illicit trade – was therefore officially closed.

Over the next few months, the governments of Niger and Benin took various escalatory measures (see Figure 2).2 The regional dispute peaked in January 2024, when the military juntas of Niger, Burkina Faso and Mali announced their decision to leave ECOWAS.3 Backed into a corner after failing to force a return to civilian rule, the regional bloc lifted most of its sanctions in late February.4 However, while Benin reopened the border on the Malanville side, the Nigerien authorities did not reciprocate.

The extended closure has fuelled the smuggling by boat of migrants as well as licit commodities across the Niger River, swelling profits from illicit transportation and bribes, while damaging the livelihoods of local traders. Northern Benin had already become an area of significant concern over the past five years, due to an increased presence of violent extremist organizations.

The border closure has had little effect on the ability of these armed groups to use Malanville as a transit point for the supply of illicitly traded commodities such as fuel.5 Individuals living in and around Malanville with pre-existing ties to extremist groups have also continued to provide them with intelligence. While there is no evidence at this stage of any increase in recruitment, economic hardship and deteriorations in community–state relations are well-known drivers of violent extremist groups’ recruitment.6

The dynamics at play at the Malanville-Gaya crossing illustrate the counterproductivity of border closures, which invariably simply fuel increases in clandestine traffic. The booming flow of migrants facilitated by smugglers across the Niger River underscores that human smuggling is among the most resilient illicit activities to external shocks. Benin cracked down in May this year on smuggling of migrants across the river. However, the principal effect of this appears to have been to drive up the price of the journey and further boost human smugglers’ profits.

Regional migration flows reshaped by insecurity

The closure of the Benin-Niger border is just the latest factor to influence regional migratory flows in recent years, however. In particular, the impact of insecurity in the Sahel region on regional mobility has been pronounced, even ahead of the closure.

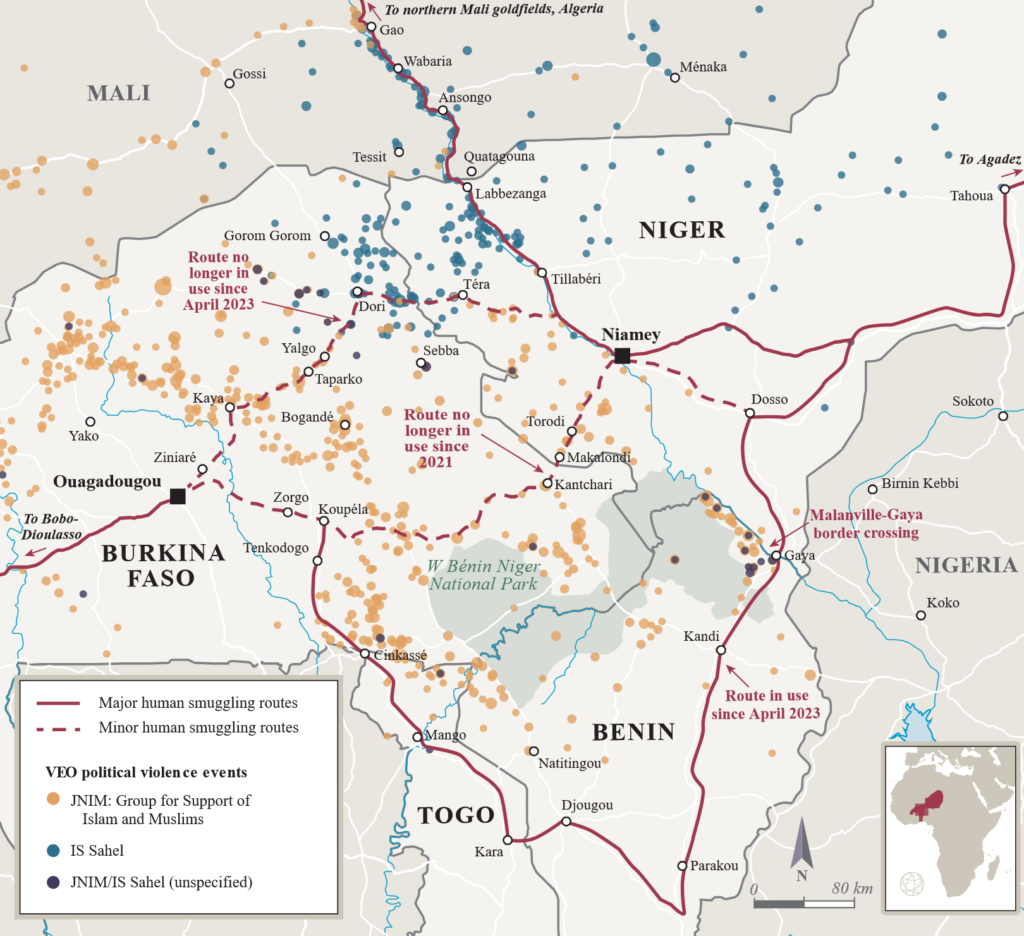

The route from Burkina Faso’s capital Ouagadougou to Niger’s capital Niamey is a key itinerary connecting coastal West African countries to Niger, and is therefore crucial to regional migratory movements. Migrants seek to move north on this route from Burkina Faso as well as other countries in the region (namely Gambia, Guinea, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali) to Niger.

Niger is the penultimate African stage – ahead of onward travel to the Mediterranean springboards of Algeria and Libya – of migrant journeys to Europe. The repeal by Niger in November 2023 of an anti-smuggling law has made the journey noticeably easier, at least once migrants have safely navigated passage into the country. The route is also popular among those aiming to reach gold-mining areas in Niger or Mali.7

Before the border closure, travelling via Benin had increased in popularity for migrants, particularly those coming from Burkina Faso.8 An increase in violence and predatory behaviour by extremist organizations – primarily Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) but also, to an extent, Islamic State Sahel Province – in Burkina Faso’s Sahel and Est regions made transiting the area highly risky for migrants travelling to Niger directly. Regional bus companies, the go-to for migrants travelling across the Sahel, were forced to adapt. In 2021, one of the main bus routes from Ouagadougou to Niamey via the city of Kantchari in eastern Burkina Faso was shut down due to threats and violence carried out by JNIM.9

An alternative route further north, via Dori in Burkina Faso and Téra in Niger, was initially used thereafter. However, JNIM also attacked buses along this route repeatedly in 2022.10 In early 2023, following a further attack by a suspected extremist organization on two buses near Dori, regional bus companies suspended services on the route.11 Bus companies and the migrants who use them turned instead to the Togo-Benin route (see Figure 1).

A large proportion of West African migrants travelling to Libya or Algeria with the objective of reaching Europe therefore travel via Benin. In 2023, internal displacement in Burkina Faso reached record levels, surpassing 2 million, with increasing numbers fleeing to neighbouring countries, Benin among them.12 While most Burkinabés fleeing insecurity are displaced internally – seeking refuge in larger towns, or settling in neighbouring countries (chiefly Côte d’Ivoire) – there has been an increase in their movements beyond the region too, including into Italy.13

Figure 1 Insecurity along routes used by bus companies between Ouagadougou and Niamey, July to December 2023.

Source: ACLED data and GI-TOC monitoring, published in Alice Fereday, Niger: Coup reverses 2015 human smuggling ban amid major political and security upheaval, GI-TOC, June 2024

Figure 2 Developments in Benin-Niger relations since July 2023.

Benin–Niger border closure strengthens smuggling industry

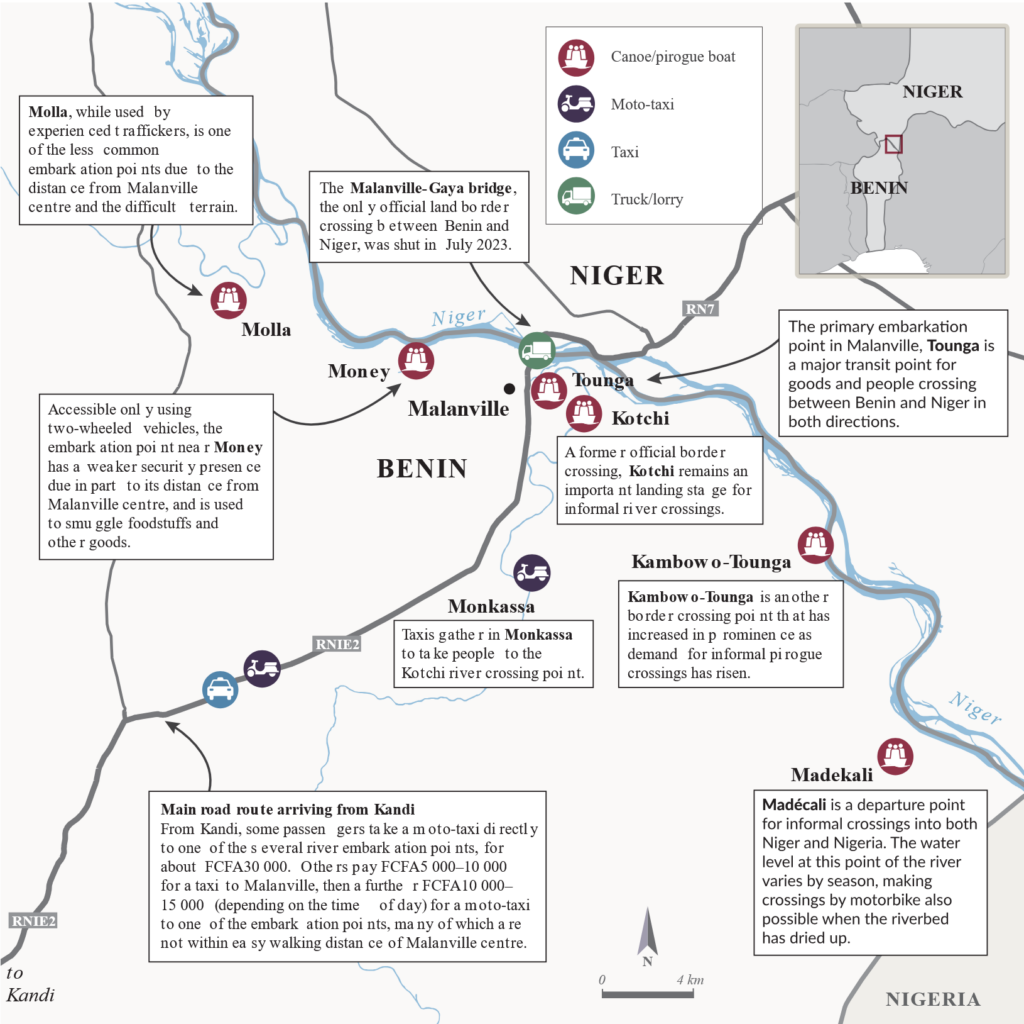

Along most of Benin’s border with Niger, the two countries are separated by the Niger River. Pirogues (wooden canoes) have long been used to smuggle goods and people across the border. The river is a significant transit point for migrants travelling north from coastal states up through Niger and on towards North Africa.14 Until the July 2023 border closure, passengers typically entered Niger over the Malanville-Gaya bridge.

While the overall number of people arriving at the Benin-Niger border (legally) from elsewhere in West Africa dipped slightly due to the bridge closure, the impact was relatively short-lived. When land travel over the bridge was halted, pirogue operators saw demand for their services skyrocket and river crossings surged. As noted earlier, the number of migrants moving via Benin had increased substantially following the closure of the Dori-Téra bus route. GI-TOC monitoring suggests that just ahead of the coup in July, between 7 000 and 8 000 people per month were entering Niger via the Malanville-Gaya bridge, compared to around 3 000 per month before April 2023.

As land crossings were halted, commercial bus operations came to a standstill. In the months after the border closure, Malanville resembled a ‘parking lot’ as trucks and buses stretched back kilometres from the border, stranded and unable to continue their journeys into Niger.15 However, the smuggling system adapted, facilitating the cross-border movement of migrants who would otherwise have been moving legally.

Local sources at the Benin-Niger border in Gaya estimate that in August 2023, around 500 passengers a day, many of whom arrived by bus from Burkina Faso and through Togo, were being smuggled across the river by pirogue, at a cost of FCFA5 000 (nearly €7.60) per passenger.16 By December 2023, up to 850 people were estimated to be crossing the river by pirogue every day – a 70% increase in just four months.17

First the bridge, then the river

On 22 May 2024, the Beninese authorities cracked down on informal Niger River crossings, which they had tolerated for the previous 10 months.18 Initially, the impact on the migrant smuggling route was pronounced, as the number of arrivals into Malanville dropped.19 ‘The closure of the river has a direct impact on our business,’ said an official from a bus company operating routes from Ouagadougou to Malanville. ‘After the news, the chiefs instructed us to temporarily close the station. If passengers cannot cross the river, there is no point in taking them to Malanville, and vice versa. Therefore, our services in Malanville are suspended until further notice.’20

However, smuggling systems adapted. With bus routes now terminating at the Beninese city of Kandi, 100 kilometres south of Malanville, taxi drivers saw a sharp rise in demand. Crossings moved further away from the official Malanville-Gaya bridge and embarkation points multiplied.21

As the risks involved in migrant smuggling increased, so did the level of organization – and profits. Pirogue crossing fees surged from FCFA1 500–FCFA2 000 (€2.30–€3.00) to FCFA3 000–FCFA5 000 (€4.50–€7.50), as did bribes payable to security officials to enable transit, which increased from around FCFA1 000 (€1.50) to FCFA3 000–FCFA4 000 (€4.60–€6) per traveller.22

People began to cross at embarkation points on the Niger River or on one of its tributaries, the Sota River or the Alibori River, further away from the official Malanville-Gaya bridge (see Figure 3).23 The crossings are often arranged collaboratively between moto-taxi drivers and the pirogue operators, and take place at night, when police surveillance is weaker.

Figure 3 River embarkation points on the Benin side of the Benin-Niger border.

Migrant smuggling resilient to insecurity and uncertainty

As of September 2024, the ban on river crossings remained in place. However, recent political developments, including reciprocal visits by delegations of both countries, suggest that bilateral tensions are de-escalating. It is therefore conceivable, if not likely, that the border will open soon.

The boom in migrant smuggling in Malanville in the wake of the border closure has strengthened relationships between key players, from moto-taxi drivers to pirogue operators, law enforcement officers and the intermediaries who keep the entire enterprise moving. Just as heightened insecurity in Burkina Faso led to a shift in migration routes towards Benin, migrants and those who facilitate their movement across borders have adapted to challenges created by the Benin-Niger border closure.

While the route via Togo and Benin is considerably safer than the previously used routes that run directly from Burkina Faso to Niger, the expansion of extremist organizations’ activity southwards from the Sahel and into the northern areas of coastal West African states generates increasingly significant risks for individuals travelling through these areas. In April 2024, for example, JNIM targeted a customs station in Monkassa, a village just south of Malanville, killing two civilians and one soldier. There have also been security incidents in Kandi and in Djougou, 30 kilometres west of the Togo border.24

Border opening key to security

Migrant smugglers’ adaptation to heightened insecurity and border closures highlights just how resilient this trade is; indeed, heightened insecurity is a key driver of migrant flows. Authorities in Benin and Niger should therefore reopen the border to allow the regular movement of people to resume, as a key step to diminishing both the volume and profitability of human smuggling.

The reopening of the border would also ease pressure on legitimate livelihoods in both countries that have been severely damaged by the bridge closure and the subsequent ban on river crossings. Such pressure has not – at least yet – triggered protests against the authorities, or any discernible recruitment drive by armed groups, but other countries’ experiences suggest that resentment towards political leaders can bolster support for violent extremist groups. The longer the border remains closed, damaging the livelihoods of local traders, the more vulnerable these residents become to recruitment.

Notes

Boureima Balima and Felix Onuah, West Africa threatens force on Niger coup leaders, French embassy attacked, Reuters, 31 July 2023. ↩

Niger denounces military cooperation agreement with Benin, Africa News, 13 September 2023; Abdoulie Sey, Cotonou port closed to Niger bound goods, APA News, 27 October 2023. ↩

Proposed ECOWAS exits leave West Africa at a crossroads, ISS Today, 8 February 2024. ↩

ECOWAS lifts sanctions on Niger amid tensions in West Africa bloc, Al Jazeera, 24 February 2024. ↩

Request for information conducted with migrants, customs and law enforcement officials, piroguiers, bus company officials and local residents, August 2024. ↩

Flore Berger, Mouhamadou Kane and Patrick Gnonsekan, Community resilience to violent extremism and illicit economies: Community resilience dialogues in Atakora (Benin) and Bounkani (Côte d’Ivoire), GI-TOC, February 2024. ↩

Ongoing GI-TOC monitoring. ↩

Alice Fereday, Niger: Coup reverses 2015 human smuggling ban amid major political and security upheaval, GI-TOC, June 2024. ↩

Alice Fereday, Niger: Regional migration and gold mining consolidate as smuggling to Libya stagnates, GI-TOC, July 2023. ↩

Niger: au moins 19 morts dans l’attaque d’un bus qui revenait de Ouagadougou, RFI, 17 March 2022. ↩

L’insécurité au Burkina pousse deux sociétés de bus nigériennes à revoir leurs trajets, RFI, 18 April 2023. ↩

UNHCR Burkina Faso, Aperçu des personnes déplacées de force au 31 juillet 2024, July 2024. ↩

UNHCR, Sahel situation: 2023 situation overview, ↩

Citizens of ECOWAS can normally travel across member states’ borders freely (provided they possess a valid travel ID), but mobility facilitators – or passeurs – are still required when natural obstacles, notably rivers, require navigation. ↩

After Niger coup, sanctions pain strikes at shutdown Benin border, Africa News, 21 September 2023. ↩

Alice Fereday, Niger: Coup reverses 2015 human smuggling ban amid major political and security upheaval, GI-TOC, June 2024. ↩

Ibid. ↩

Judicaël Kpehoun, Frontière Bénin-Niger: voyageurs et colis en souffrance à Malanville, Banouto, 24 May 2024. ↩

The decision to block river crossings was accompanied by a prohibition, imposed by authorities in Malanville, on buses arriving and departing the area. ↩

Interview with a bus company official, Malanville, May 2024. ↩

Initially, some passengers sought to cross into Niger via Nigeria, crossing into the latter through Segbana, but this was short-lived, given the long route and the high prevalence of road checkpoints on the Nigerian side of the border. Request for information conducted with migrants, customs and law enforcement officials, piroguiers, bus company officials and local residents, August 2024; Interview with security researcher in northern Benin, August 2024, by phone. ↩

Interview with a migrant, Malanville, August 2024; Request for information conducted with migrants, customs and law enforcement officials, piroguiers, bus company officials and local residents, August 2024; Interview with security researcher in northern Benin, August 2024, by phone. ↩

Interview with security researcher in northern Benin, August 2024, by phone. ↩

Data from ACLED. ↩