Key Takeaways:

- Democratic Republic of the Congo. The FARDC and allied militias launched an offensive operation on September 26 against a Rwandan rebel group in eastern DRC. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) may have launched the offensive against the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) to advance ongoing peace talks aiming to end the conflict in the eastern DRC among the DRC, Rwanda, and their proxies. An anti-FDLR offensive has been a key Rwandan demand in peace talks because Rwanda’s Tutsi-dominated government views the FDLR as a threat. The Rwanda-backed and predominantly Rwandaphone M23 rebellion has made significant gains against the Congolese army in the eastern DRC since Rwanda began backing the group to counter the FDLR in 2021, creating an incentive for Kinshasa to advance peace talks.

- Ethiopia. The Ethiopian National Defense Force launched a counteroffensive against ethno-nationalist insurgents known as Fano in Ethiopia’s northwestern Amhara region. Fano has maintained attacks against the Ethiopian military in the region and likely seeks to establish control over key lines of communication to degrade the federal government’s access to Amhara region. Negotiations between Fano and the Ethiopian government are not progressing, and both sides are unlikely to reach an agreement in the coming months.

- Somalia. Partners for the new AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia disagree on Egypt’s role as a troop-contributing country and funding for the mission as the November 15 deadline to submit the mission plans to the UN Security Council approaches. Egypt replacing Ethiopia in the African Union (AU) mission would exacerbate the growing tensions among Egypt, Somalia, and Ethiopia, and between the Somali Federal Government and local administrations. Egypt taking a large role in the mission would also likely disrupt the mission structure and initially degrade its effectiveness as Egyptian troops and potentially other troop-contributing countries acclimated to a new operating environment and a rearranged AU mission structure.

- Mali. JNIM launched three simultaneous attacks against Malian and Russian bases across northern Mali, including its first suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device attack in northern Mali since September 2023. All three attacks failed. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM) said the attack was retaliation for Malian and Russian atrocities against civilians, framing itself as a protector to gain popular support. JNIM launched the attack as security forces are preoccupied with threats in other areas of northern Mali.

- Togo. JNIM conducted its second-deadliest attack in Togo, killing at least nine Togolese and Turkish soldiers. The attack is likely part of an effort to degrade Togolese border security and strengthen its cross-border rear support zones. JNIM will likely increase the rate and severity of its attacks in Benin and Togo in the coming months as the area enters the dry season.

- Assessments:

Democratic Republic of the Congo

FARDC and allied militias launched an offensive operation on September 26 against a predominantly Rwandan Hutu rebel group in eastern DRC. France-based investigative outlet Africa Intelligence reported that the Congolese army’s (FARDC) offensive aims to capture Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) Commander Pacifique Ntawunguka and will last six months.[1] Fighting since the beginning of the offensive has centered on the Lushagala refugee camp near the provincial capital of Goma. French media reports that 85 percent of the nearly 80,000 refugees at the camp have fled to safety.[2]

The FDLR is a predominantly ethnic Hutu armed group based in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) with ties to the former officers and soldiers in the Rwandan Armed Forces, who are widely condemned for their role in the 1994 Tutsi genocide.[3] The rebel group is an irredentist movement that claims its military activity aims to “drive inter-Rwandan dialogue,” but most international observers believe it aims to topple the Rwandan government.[4] The FDLR uses guerrilla tactics to attack state forces, mostly Rwandan, and vulnerable villages in remote areas rather than direct combat with larger forces.[5] The group is concentrated in the lower territories of North Kivu near the Rwandan border known as “Petit Nord,” and the UN estimates it has 1,000 to 1,500 fighters.[6]

The DRC may have launched the offensive against the FDLR to advance ongoing peace talks aiming to halt the conflict in the eastern DRC between the DRC, Rwanda, and their proxies. Angola has been mediating peace talks known as the Luanda Process between the DRC and Rwanda since July 2022.[7] The talks resulted in a ceasefire agreement between the DRC and Rwanda that went into effect on August 4.[8] However, fighting between FARDC and Rwandan-backed M23 rebels resumed on August 25 with each side blaming the other for failing to abide by the agreement.[9]

FARDC action against the FDLR has been a major component of peace talks. Political and intelligence officials from the DRC and Rwanda have since met secretly and under the Luanda Process framework multiple times to solidify an agreement for FARDC to target the FDLR and for Rwandan troops to withdraw from the eastern DRC.[10] Angolan, Congolese, and Rwandan officials finalized the plan on September 14 and stipulated that FARDC would attack the FDLR and that the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF) would withdraw from the DRC five days later.[11] The Congolese foreign minister refused to sign the final agreement, however, arguing both aspects of the agreement should be implemented simultaneously.[12] The foreign minister also accused Rwanda of derailing the peace process by offering “no guarantees or concrete details” about the RDF’s withdrawal and claimed Kigali conditioned the RDF’s disengagement on FARDC’s offensive against the FDLR.[13] Both sides have agreed to attend the next slate of ministerial meetings in Luanda on October 12.[14]

An anti-FDLR offensive has been a key Rwandan demand in peace talks because Rwanda’s Tutsi-dominated government views the FDLR as a threat due to the DRC’s use of the FDLR as an anti-Rwandan proxy, the FDLR’s ties to the Rwandan genocide, and the group’s anti-Tutsi ideology. The DRC has financed and supplied the FDLR since 2006 as a proxy to counter Rwanda and Rwandan-backed rebels operating in eastern DRC.[15] The UN and United States have sanctioned the FLDR since 2003 and 2006, respectively, and long called on the DRC to cease collaboration with the group due to human rights abuses and illegal taxation networks.[16] Kigali has accused the Congolese government of using the FDLR as a proxy to destabilize or even overthrow the Rwandan government.[17] Rwanda has also alleged that the United Nations intervention force and Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops have collaborated with the FDLR, representing a direct threat to Rwanda and an obstruction to peace in the eastern DRC.[18]

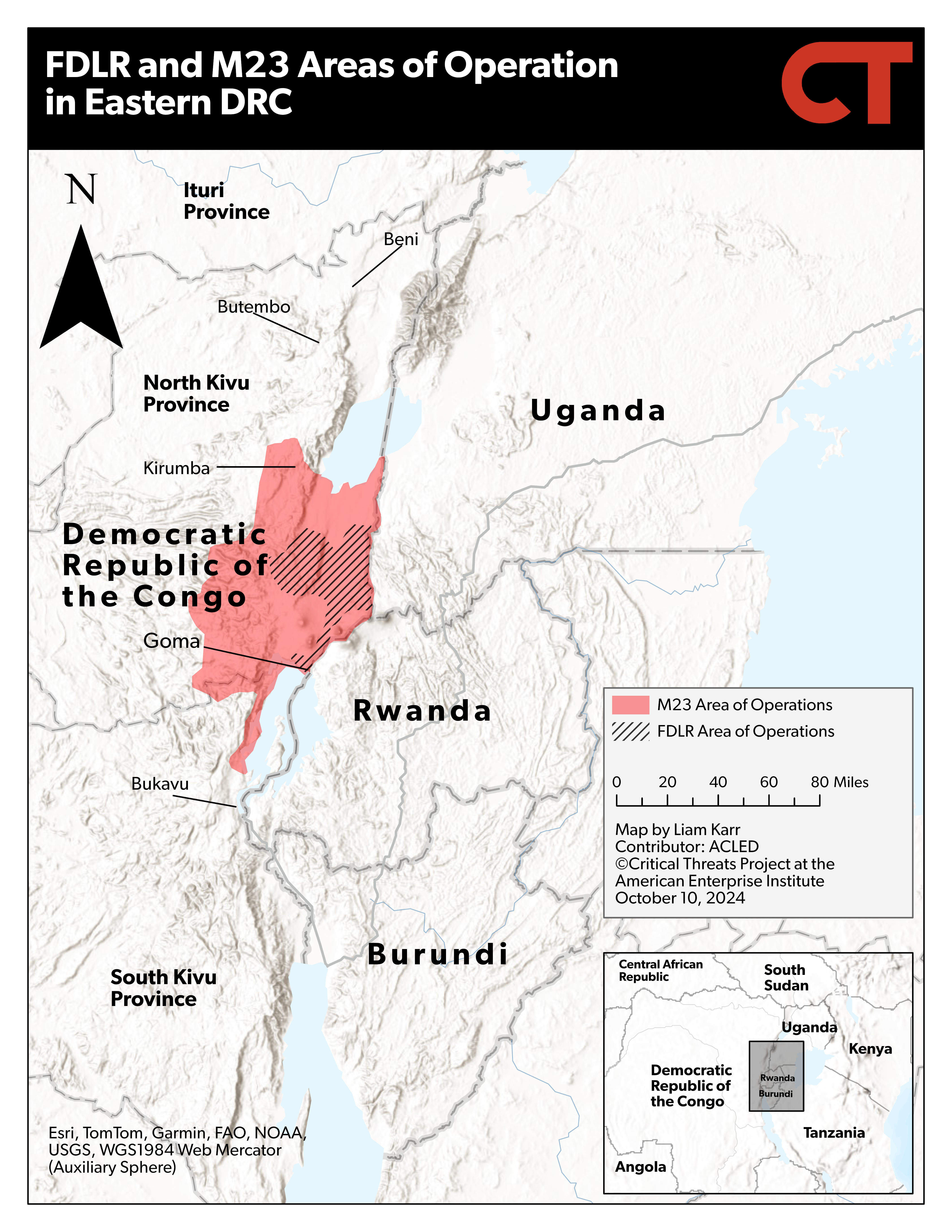

Figure 1. FDLR and M23 Areas of Operation in Eastern DRC

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The Rwanda-backed and predominantly Rwandaphone M23 rebellion has made significant gains against the FARDC in the eastern DRC since Rwanda began backing the group to counter the FDLR in 2021, which is an incentive for Kinshasa to advance peace talks.[19] M23 is an armed rebellion that was established in 2012 following the failed integration of predominantly Tutsi fighters into FARDC.[20] The failed integration effort is one of many grievances among the Tutsi and other minority Rwandaphone communities that feel marginalized and violently discriminated against in the eastern DRC.[21]

The M23 rebels reemerged in November 2021, after several years of dormancy, when negotiations between M23 and the DRC government collapsed. The rebels claimed that a sudden offensive by FARDC and worsening insecurity in the eastern DRC necessitated the use of armed force to defend themselves and their communities.[22] M23 further alleged that Kinshasa failed to meet the group’s long-standing political demands, including the repatriation of its members exiled abroad and the safe return of Congolese Tutsi refugees from neighboring countries.[23] M23 leaders have also demanded that the Congolese government repress FDLR militants that threaten Tutsi populations in the east.[24]

Kigali began supporting the M23 insurgency in 2021 after a brief honeymoon period with newly elected Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi ended. Congolese and Rwandan forces conducted joint operations against the FDLR after Tshisekedi became president in 2019. However, this cooperation ended in mid-2021 when Rwanda perceived the strengthening economic and security partnership between the DRC and Uganda as a threat to its economic and security interests.[25] Uganda deployed troops in the eastern DRC in 2022 to combat IS Central Africa Province, locally known as the Allied Democratic Forces, which has its historical roots in Uganda and carried out suicide bombings in Kampala in 2021. Rwanda viewed the deployment and growing ties as infringing on its sphere of influence.

The DRC and international partners including the UN and United States have accused Kigali of infringing on the DRC’s territorial integrity through its support of M23 and the covert deployment of RDF troops on Congolese soil to support M23.[26] The UN and United States have repeatedly accused Kigali of deploying an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 RDF troops to support M23 and providing the group with training and military equipment based on aerial footage and M23’s use of advanced military technology.[27] Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project data indicate the RDF conducted at least a dozen joint operations with M23 from November 2021 to March 2023.[28] Kigali denies that it provides logistic or military assistance to the group but has voiced support for the demands of an M23-aligned political movement known as the Congo River Alliance.[29]

Kinshasa has failed to substantially degrade the M23 insurgency. The estimated 3,000 M23 insurgents have rapidly consolidated control over sizable swaths of territory in North Kivu since 2021, gradually pushing southward toward the provincial capital, Goma.[30] Petit Nord has been the region most affected by violence as M23 rebels routinely clash with FARDC and allied militia groups for control over strategic military positions, lucrative mining zones, and key supply and trade routes near Goma.[31] The UN and other international experts tripled the territory under its control in 2022 and then further expanded operations and has since grown its territorial control by at least another 70 percent since a six-month ceasefire broke down in October 2023.[32] This growth includes significant gains around Goma in 2024 that have involved heavy fighting around refugee camps used by FARDC and allied armed groups as de facto military bases.[33]

The Congolese government has sought to gain local and international allies to boost its military capacity and increase diplomatic pressure on Rwanda to halt the M23 advance. Kinshasa has co-opted FDLR militants and partnered with dozens of loosely organized militia groups claiming to total of 40,000 fighters known as the “Wazalendo,” who have launched attacks against M23.[34] Kinshasa has also invited foreign troops to repel M23, including the East African Community Regional Force (EACRF) and SADC troops. However, the EACRF withdrew in December 2023 after Tshisekedi criticized the EACRF for not confronting M23 in enough kinetic engagements despite its successes in reclaiming M23-held territory.[35] Tshisekedi has also called for international policymakers to impose “targeted sanctions” on Rwanda for backing M23.[36] He has also sought to discredit M23’s raison d’être by claiming that the Congolese government can protect Congolese Tutsi interests and accusing M23 of “always playing the victim to make business out of it.”[37]

Ethiopia

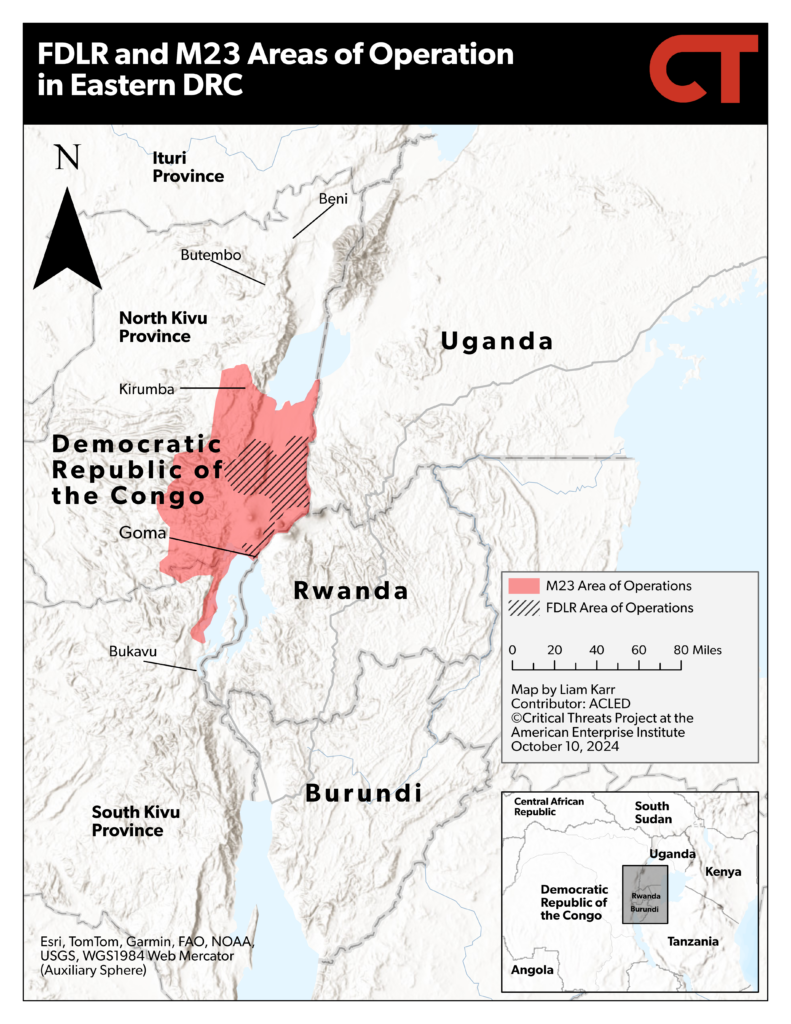

The ENDF launched a counteroffensive against ethno-nationalist insurgents known as Fano in Ethiopia’s northwestern Amhara region.[38] The Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) and the regional Amhara government said on October 1 that they will “intensify” operations against leaders of Fano militias, individuals who support the militias, and individuals who provide Fano with logistic support and information.[39] The ENDF launched the counteroffensive to degrade Fano militarily, retake territory from Fano, and target support networks that could help Fano reconstitute itself in the future. The ENDF is using the counteroffensive to push Fano to peace talks. The ENDF spokesperson said that “for peace to prevail, they [Fano] need to be met with force.”[40] Fano has waged a mostly low-level insurgency in northern Ethiopia’s Amhara region since August 2023.[41] Fano launched an offensive in July 2024 that included expanding control over several key roadways and attacking Ethiopia’s second-largest city in September.[42] The ENDF has doubled operations against Fano in the region between mid-September and early October, shortly after Fano attacked Ethiopia’s second-biggest city, Gondar, on September 16.[43] The ENDF conducted five operations against Fano between September 20 and September 26, compared with 13 operations between September 27 and October 3.[44]

The ENDF has also used nonmilitary means to cut off potential support for Fano and disrupt Fano’s communications. The ENDF initiated a major arrest campaign targeting suspected Fano fighters, as well as civilians and government officials suspected of supporting or collaborating with Fano. Amnesty International reported that the Ethiopian military and police forces have arbitrarily arrested hundreds of people across the Amhara region since September 28.[45] An Ethiopian journalist also reported internet outages in some parts of the Amhara region.[46]

Figure 2. ENDF Campaign Against Fano in the Amhara Region

Source: Kathryn Tyson; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

add note

tweet

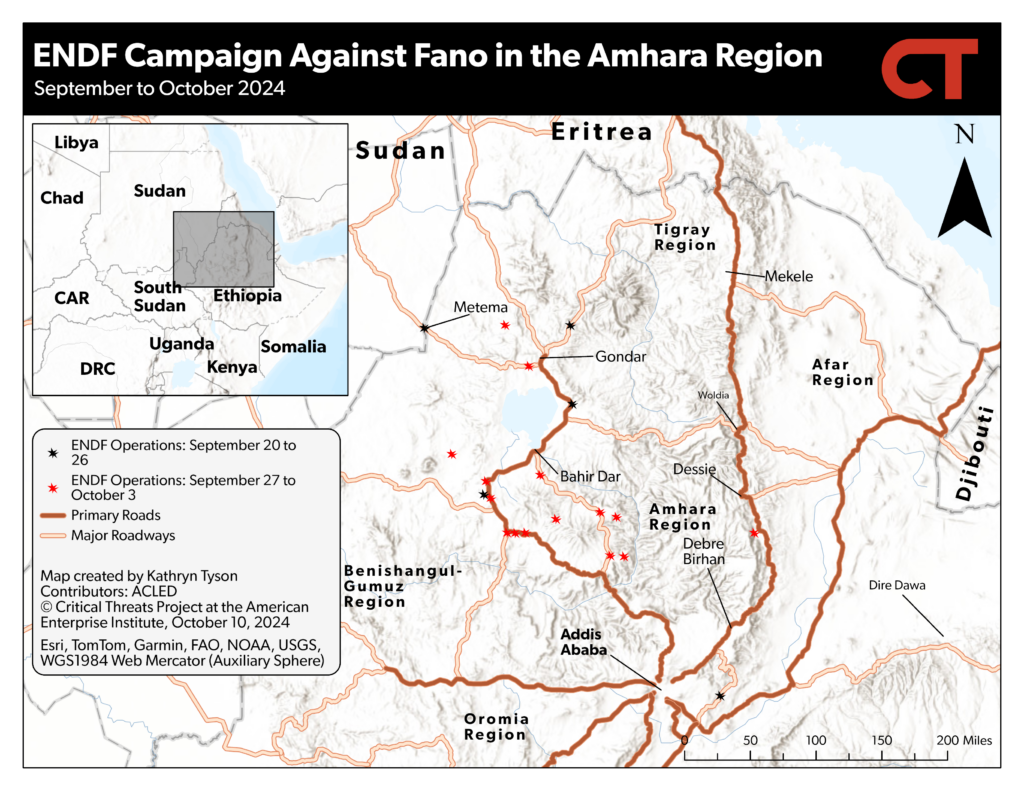

Fano has maintained attacks against the Ethiopian military in the region and likely seeks to establish control over key lines of communication to degrade the federal government’s access to Amhara region. Fano attacks have remained at consistent levels since the ENDF launched its campaign on October 1. Fano conducted 16 attacks targeting the ENDF from September 20 to 26, compared with 21 attacks from September 27 to October 3.[47] Pro-Fano media has also reported that Fano has continued temporarily seizing control of towns in the Amhara region.[48] Fano has also looted weapons and ammunition from ENDF bases and ENDF-controlled towns to resupply itself for further attacks.[49] Fano continues to target the ENDF on key east–west highways in Amhara and the A3 and B31 highways, the two major north–south highways between the Amhara region and Addis Ababa.[50] Fano announced on October 3 the closure of all major highways in Amhara for nonemergency purposes following the ENDF campaign.[51]

Figure 3. Fano Attacks Targeting the ENDF in the Amhara Region

Source: Kathryn Tyson; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Negotiations between Fano and the Ethiopian government are not progressing and both sides are unlikely to reach an agreement in the coming months. Fano’s primary objective—advancing Amhara ethno-nationalist interests through armed resistance—is at odds with the ENDF, which seeks to disarm and dismantle Fano.[52] There are several obstacles to ending the fighting. The federal government created a 15-member peace council in June 2024 to facilitate negotiations that have not made significant progress.[53] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said talks were taking place in August 2024, but a Fano spokesperson denied participating in such talks.[54] Fano lacks a centralized command structure and does not have formal leadership to negotiate with the federal government.[55] Internal disputes within Fano have also hindered attempts to negotiate with the government.[56]

The ENDF also launched a similar campaign in 2023, which temporarily degraded Fano Ethiopian forces arrested suspected Fano fighters and supporters in 2023 before the group reconstituted and began high levels of attacks on the ENDF. The ENDF said on October 1 that Fano’s “urban cells are relocating to rural areas” which will help the group establish “escape routes,” presumably referring to areas to which Fano can retreat.[57] The ENDF also said that Fano has “intensified propaganda.” Pro-Fano media have reported some defections from regional governments to Fano, but CTP-ISW cannot verify these reports.[58] CTP previously warned that a heavy-handed and military-focused counterinsurgency strategy would likely exacerbate the grievances driving the insurgency in the long term.[59]

Somalia

Partners for the new AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia disagree on Egypt’s role as a troop-contributing country and funding for the mission as the November 15 deadline to submit the mission plans to the UN Security Council approaches. The African Union (AU) Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) is supposed to succeed the outgoing AU Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) on January 1, 2025, when the ATMIS mandate expires at the end of 2024. The AU Peace and Security Council endorsed plans for AUSSOM in June 2024 due to concerns that ongoing counterinsurgency offensives and a simultaneous withdrawal of international forces at the end of 2024 would leave gaps that al Shabaab could exploit.[60] The AU adopted a strategic concept of operations for AUSSOM in early August and forwarded the concept to the UN Security Council for approval in mid-August.[61] A joint UN-AU mission traveled to Somalia in early October ahead to continue discussions on the mission’s composition and funding with key local, regional, and international stakeholders.[62]

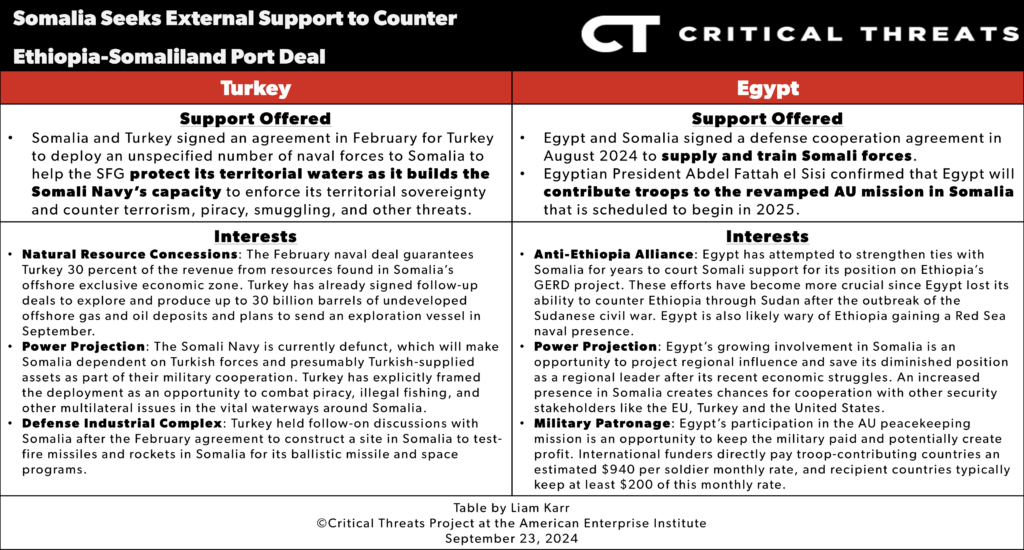

Some partner countries disagree with Egypt’s inclusion in the new mission due to Egypt’s role in the Ethiopia-Somalia dispute and Egypt’s lack of involvement in prior missions. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi confirmed in August that Egypt planned to contribute troops to the revamped AU mission in Somalia that is scheduled to begin in 2025.[63] International and regional outlets have reported that 5,000 Egyptian troops will deploy to Somalia as part of the mission, which would be nearly half of the planned 11,146 military force.[64]

The Somali Federal Government (SFG) and Egypt have increased military cooperation to counter Ethiopia throughout 2024. after the SFG aims to counter Ethiopia’s memorandum of understanding for a naval base with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region in northern Somalia that Ethiopia signed in January 2024.[65] The SFG has repeatedly called the deal a violation of Somali sovereignty. Egypt has attempted to strengthen ties with Somalia for years to court Somali support to counter Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project.[66] Egypt has repeatedly labeled the GERD an existential threat that will degrade—or enable Ethiopia to control—its Nile water supply, which is vital for Egypt’s economy and general population.[67] The SFG and Egypt have signed several agreements since August that aim to enable Somalia to expel and replace the 8,000–10,000 Ethiopian troops fighting al Shabaab in Somalia with Egyptian forces and threaten Ethiopia by allowing Egypt to pose a military threat on Ethiopia’s border.[68]

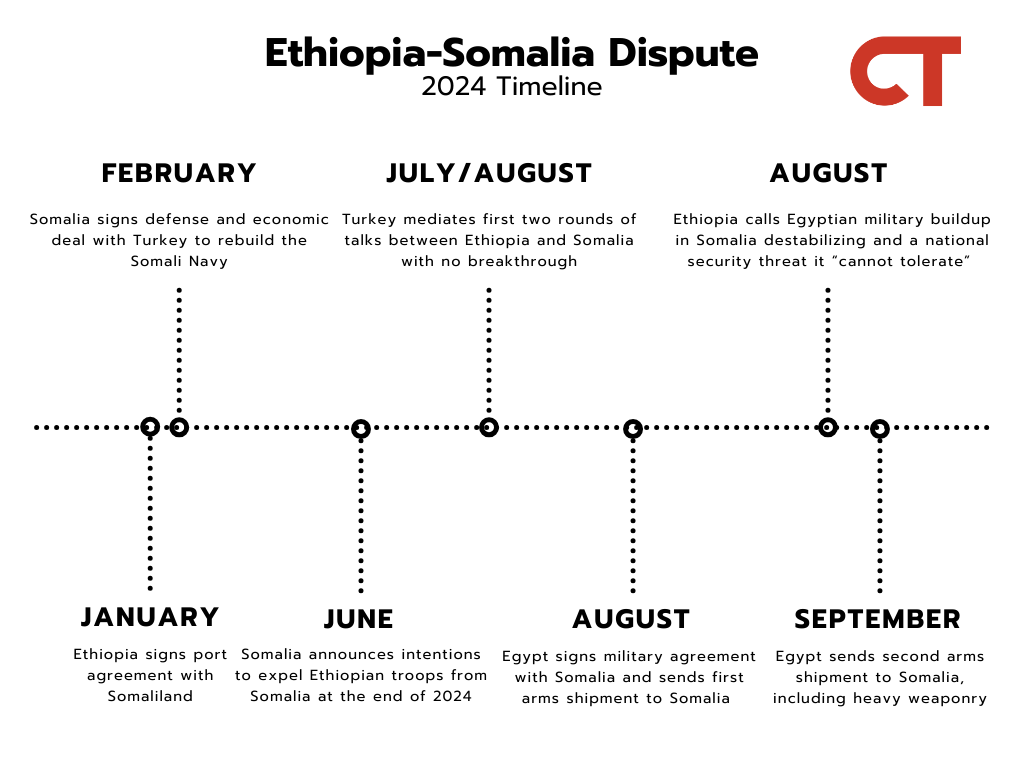

Figure 4. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

Regional troop-contributing countries (TCCs) have criticized Egypt’s potential inclusion in the mission. Some international and regional partners warned that Egypt’s inclusion would give Egypt a victory in its rivalry with Ethiopia and undermine the main objective of the mission to counter al Shabaab.[69] Uganda’s foreign minister also argued that Egypt’s inclusion in the mission would disrupt the mission’s structure given that the current TCCs have been working together, each in the same area of Somalia, for a decade.[70] The foreign minister alluded to both criticisms when saying “why does Egypt want to join now, where have they been all this time” in comments to a Kenyan-based news site.[71] However, the AU already provisionally accepted Egypt’s offer in August.[72]

Figure 5. Somalia Seeks External Support to Counter Ethiopia-Somaliland Port Deal

Source: Liam Karr.

Egypt replacing Ethiopia in the AU mission would exacerbate the growing tensions among Egypt, Somalia, and Ethiopia, and between the Somali Federal Government and local administrations. Ethiopia believes the change would undermine its security against al Shabaab. CTP previously assessed that Ethiopian forces will almost certainly try to remain in Somalia to maintain a buffer zone against al Shabaab and prevent an al Shabaab offensive into Ethiopia, as the group launched in 2022.[73]

Ethiopia has also repeatedly warned that Egypt’s growing military presence in Somalia poses a national security threat and warned Egypt and the international community against including Egypt as part of the new AU mission.[74] Reports have varied as to where the Egyptian contingent of the mission will deploy.[75] One option is Egypt deploying to the Ethiopian forces’ area of operations in a direct swap. This course would alarm Ethiopia, given Ethiopia is primarily responsible for nearly all sectors in Somalia that border Ethiopia, meaning Egyptian troops would take control of these areas.

Several Somali federal member states that host Ethiopian troops have also rejected the proposed swap.[76] Multiple leaders and politicians in Somalia’s Jubbaland and South West states have spoken out against the SFG’s plans to expel Ethiopian troops.[77] The SFG has already begun retaliating against local politicians speaking out in favor of Ethiopia, marginalizing these communities and increasing the risk of an internal conflict.[78] Many of the Somali forces that operate in these states alongside Ethiopian soldiers respond to their clan and regional leaders, not federal entities, such as the Somali National Army or the SFG.[79] Disagreements between the federal government and these local factions have historically led to clashes between local and national forces, often the local factions receiving external backing from Ethiopia or Kenya.[80]

Egypt taking a large role in the mission would also likely disrupt the mission structure and initially degrade its effectiveness as Egyptian troops and potentially other TCCs acclimate to a new operating environment and a rearranged AU mission structure. The alternative to Egypt assuming control of Ethiopia’s sectors in the current mission is Egypt deploying to a different part of Somalia, where current TCCs operate, and reassigning one of those countries to cover Ethiopia’s former areas. This change eliminates the relationships and understanding that the national contingents of the TCCs have developed with local leaders and civilians in their areas of operations. The impact would be especially salient given the complex and unique nature of Somalia’s clan politics.

International partners have also still not agreed on the mission’s funding mechanisms. The US State Department released a statement along with Qatar, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and the UK that emphasized the urgent need to finalize funding options for the new mission.[81] Western partners aired concerns about continuing to fund a new mission due to worries about long-term financing and sustainability, leading the AU and EU to push for member-contribution funding.[82] The AU had previously said that it planned to fund the mission through UN-assessed contributions instead of relying on specific donors.[83] UN-assessed contributions are pools of money shared among the member states based on their gross domestic product that the UN General Assembly determines is needed to finance an approved expense.[84]

Mali

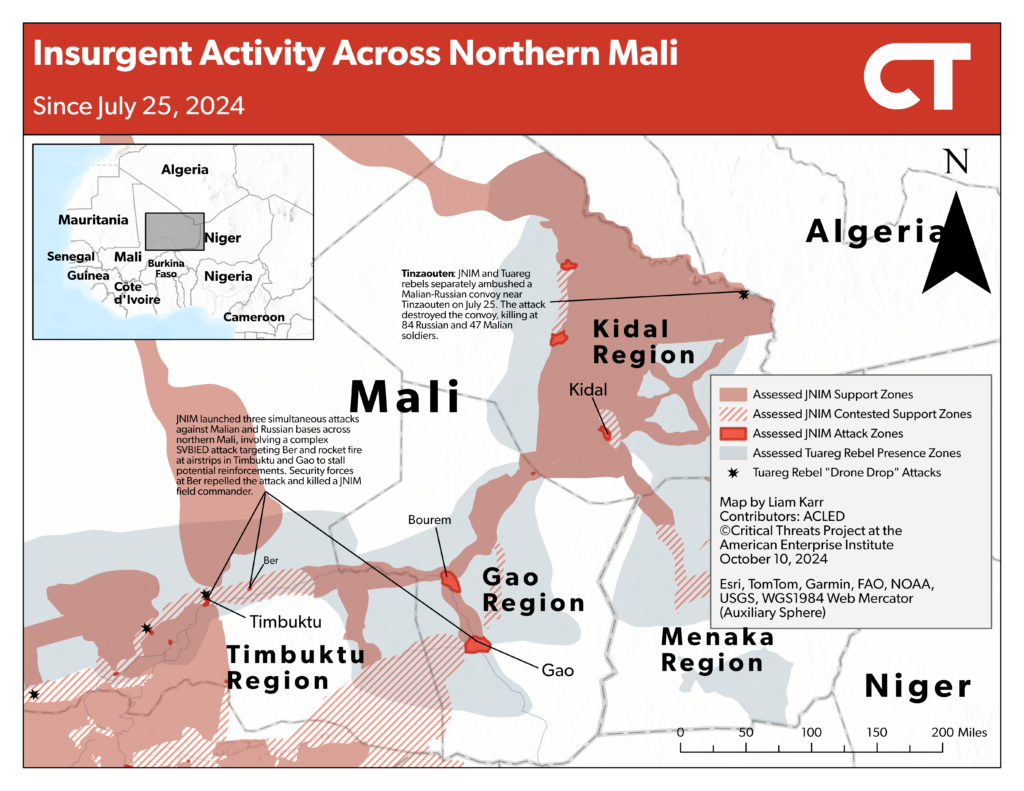

JNIM launched three simultaneous attacks against Malian and Russian bases across northern Mali, including its first SVBIED attack in northern Mali since September 2023. All three attacks failed. The main Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM) attack targeted the military base in Ber, beginning with three suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs) followed by additional militants. JNIM simultaneously targeted the airstrips at military bases in Timbuktu and Gao with rockets, 34 and 200 miles away from Ber, respectively. These secondary attacks aimed to prevent air aid from reaching the main attack at Ber. JNIM was unable to enter the Ber base, and none of the rockets hit their targets in Gao and Timbuktu.[85] Malian forces also killed a JNIM field commander during the fighting. The attack was the first SVBIED attack in northern Mali since September 2023.[86]

JNIM said the attack was retaliation for Malian and Russian atrocities against civilians, framing itself as a protector to gain popular support. The JNIM emir for the Timbuktu region called the attack “a legitimate and natural response to the massacres and crimes perpetrated by this junta and its allies” in the statement claiming the attack.[87] JNIM framed its September 17 attacks in the Malian capital, over 425 miles south of Timbuktu, in similar terms. The group noted in its claims that it inflicted losses on the “Wagner mercenaries” at the air base, destroyed a drone, and avenged “the hundreds of massacres and slaughters perpetrated by this junta and its Russian allies against our Muslim people.”[88]

Figure 6. Insurgent Activity Across Northern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

JNIM launched the attack as security forces are preoccupied with threats in other areas of northern Mali. A significant number of Malian and Russian forces have been operating in far northern Mali’s Kidal region since the end of September. Two Malian and Russian convoys consisting of more than 70 vehicles and at least 500 Malian, Russian, and pro-government Tuareg militia fighters deployed from Gao on August 30 and arrived in the northernmost regional capital, Kidal, on September 12.[89] The convoy then departed from Kidal city on September 29 and traveled eastward to Tin Essako before traveling north toward the town of Tinzaouten, along the Algerian border.[90] CTP assessed that militants with likely ties to both al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate and the Tuareg separatist rebel coalition participated in an ambush on July 26 near Tinzaouten that repelled the previous Malian-Russian offensive in this area and killed at least 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers.[91] However, the convoy retreated back to Kidal on October 8 after claiming to retrieve the bodies of Malian soldiers that died in the July ambush.[92]

Tuareg rebels have also begun attacking Malian and Russian bases across the Timbuktu region using drones to drop improvised explosive devices. Tuareg rebels first debuted the tactic in the July ambush at Tinzaouten.[93] The rebels have carried out five more “drone drop” attacks on security force bases in Timbuktu since the beginning of September.[94] The rebels have targeted bases at Goundam and Lere twice each, and the base at Timbuktu city once. CTP previously noted that the new tactic enables the group to conduct indirect fire to harass or fix security force units given they lacked mortar capabilities.[95]

Togo

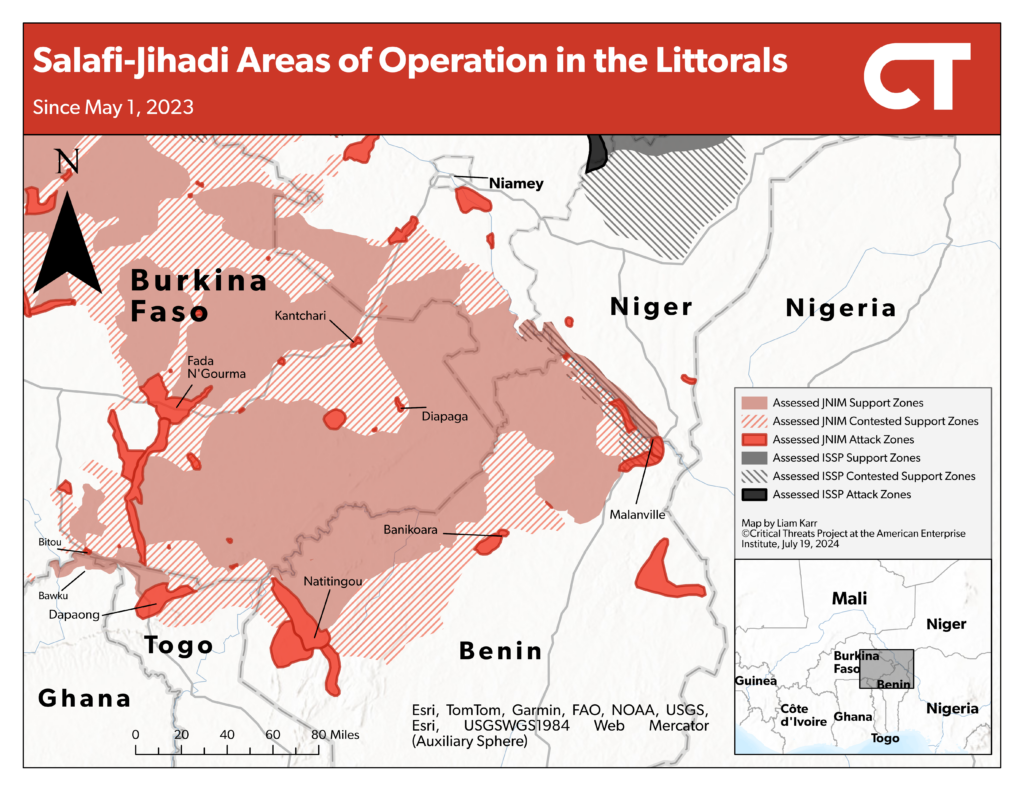

JNIM conducted its second-deadliest attack in Togo. The group attacked a construction site near Fanworgou village in northern Togo near the Burkinabe border. The attack killed at least nine soldiers and 10 civilians.[96] Most of the civilians were either caught in the crossfire or construction employees. JNIM’s deadliest attack in Togo killed 31 civilians in northern Togo in February 2023.[97]

The attack is likely part of an effort to degrade Togolese border security and strengthen its cross-border rear support zones. Burkinabe construction company Ebomaf had been constructing trenches and other obstacles around Fanworgou designed to keep insurgents from crossing the Burkinabe border into northern Togo.[98] The attack was JNIM’s first direct-fire attack on Togolese security forces since it killed 12 soldiers in an attack on a border post in July 2024.[99] The UN reported in July 2024 that JNIM cells based in Burkina Faso carry out most of the group’s attacks in the littoral countries to access resources and logistic corridors essential for expansion.[100] CTP previously assessed that the JNIM militants in southeastern Burkina Faso had likely strengthened their support zones, enabling them to carry out more regular and more severe attacks in Togo.[101]

A lack of cross-border cooperation has contributed to JNIM’s strengthening cross-border activity. Burkinabe and Togolese cross-border military cooperation has largely stopped since Burkina Faso’s 2022 coup, strengthening JNIM’s havens along the border.[102] Togo has expressed interest in resuming cooperation with Burkina Faso to address the growing insecurity.[103] The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project recorded two Burkinabe cross-border operations into Togo in June for the first time since the 2022 Burkinabe coup, but Burkinabe forces have not sustained these operations. Togo sporadically carries out clusters of drone strikes on Burkinabe territory, but these are also not sustained.

Figure 7. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Littorals

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

JNIM will likely increase the rate and severity of its attacks in Benin and Togo in the coming months as the area enters the dry season. JNIM has also used its support zones in Burkina Faso to strengthen its cross-border activity in Benin. The group carried out its deadliest attack against Beninese security forces in July 2024 when it killed 12 rangers near the Mekrou River. The rainy season in northern Benin and northern Togo generally runs from May through October.[104] Seasonal rains often degrade access to and from JNIM’s support zones in the park networks along the borders of Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Togo.[105] JNIM significantly increased its rate of attacks in Benin during the most recent dry season, averaging over 14 attacks per month, compared with less than four attacks per month during the 2024 rainy season.[106]

Stronger rear support zones in northern Togo and other littoral states creates the risk that JNIM uses these support zones to expand farther south in the future. Insurgents can use these havens to project force deeper into the littoral states, capitalize on local grievances as they arise, and gradually increase their sway over local communities. Increased local traction would presumably increase the likelihood that local JNIM militants pursue local objectives in the littoral states as opposed to using the area as a rear support zone. JNIM also used these support zones to increase to escalate their activity against Benin and Togo in response to heightened counterinsurgency activity in 2022, highlighting their ability to give priority to activity in the littoral states as it sees fit.[107]

Local media reported that JNIM killed at least two Turkish soldiers in the attack in northern Togo. The Togolese investigative outlet L’Alternative reported that the attack killed two Turkish soldiers who were a part of the construction site security team.[108] Multiple open-source analysis X accounts circulated images of the attack and claimed that they showed the dead Turkish soldiers.[109] The France-based diaspora outlet Afrik.com also reported that Turkish-piloted combat helicopters helped force the JNIM attackers to retreat across the border.[110] Togo signed a military agreement with Turkey in 2021 to improve logistic and industrial capacity and received two Bayraktar TB2 drones in 2022.[111] Africa Intelligence reported in mid-July 2024 that Togo was “increasingly relying on Turkish military experts to help it safeguard its northern borders.”[112] L’Alternative reported that these soldiers instruct Togolese forces, clear mines, and pilot helicopters.[113]

Turkey’s efforts intersect with US efforts to bolster border security in Benin and Togo. The United States has leveraged programs like the Global Fragility Act (GFA) to offer military aid that aims to enable nonmilitary projects to increase community resilience and target the root grievances that JNIM capitalizes on to recruit.[114] Benin and Togo are two of five coastal West African countries that receive support from the GFA.[115] The US Departments of State and Defense and the US Agency for International Development implement targeted development, political, and security assistance to recipient countries through the GFA.[116] US Africa Command Commander Gen. Michael Langley and the US ambassador to Togo led a delegation meeting with the Togolese president, military chief of staff, and other leaders in August 2023 as part of these efforts.[117] The United States is more militarily engaged in Benin, where it is refurbishing an air base and helping medevac and advise Beninese forces.[118]