To modernize the U.S.-Africa relationship, U.S. diplomatic and development efforts should prioritize AI-powered technologies and the broader digital transformation.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) and the broader digital transformation are rapidly shaping the future of Africa with profound implications for U.S. national strategic, security, and economic interests. As a result, U.S. policymakers should elevate Africa’s weight within the U.S. foreign policy development process and AI should take center stage. This shift is in both America’s stated interests and the interests of African nations.1 If the United States does not meaningfully engage in shaping the continent’s digital landscape and AI ecosystem, then the world’s malign actors will.

Increasingly, embedding AI and other digital technologies into the foundation of U.S. diplomacy and foreign assistance efforts in Africa will accelerate development gains in high-priority sectors, most critically in trade and investment. Increasing trade and investment flows between the United States and Africa will help redefine U.S.-Africa relations from an aid-based relationship to one rooted in mutually beneficial economic interests and shared values. To do so, however, will require the political will and commitment to modernize how the State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and other agencies integrate emerging technologies into their programs and engage their partners, the private sector, and African governments and organizations in ways that take advantage of the transformative power of AI technologies.

AI will affect every aspect of the continent’s population, including areas vitally important to U.S. development and diplomatic strategic objectives, and other global players are already heavily influencing the AI environment throughout Africa. It is time for policymakers and development practitioners to get very serious (and very quickly) about AI in Africa.

Why Should the United States Embrace AI in Africa?

The relationship between the United States and Africa needs to evolve. AI, along with the broader digital transformation, offers a vehicle to accelerate this evolution. AI can help realize significant strategic and commercial opportunities for the United States, deliver extraordinary development gains and job creation for Africa, and offer a viable alternative to China’s opaque economic partnership practices.2

Historically, U.S. engagement in Africa has focused largely on social programming—and to great effect. The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief and the President’s Malaria Initiative have saved millions of lives.3 USAID disaster and humanitarian assistance has delivered lifesaving help to those in acute need and reflected American values in the process, which should be a point of pride for all Americans. To be clear, these priorities remain important, and U.S. development agencies should continue to support partner countries’ efforts to plan, finance, and execute their own development agendas. Embracing AI will only make these efforts better, faster, cheaper, more efficient, and more precise.

However, American policymakers have rarely prioritized economic ties with Africa, which has led other global actors to step in to fill the void. Any conversation with African leaders or citizens of any background will turn to the idea that African countries want “trade, not aid.”4 They want help in achieving self-reliance rather than remaining dependent; they would prefer a “hand up, not a hand out.”5 Moreover, they most certainly want to do business with America. At the Carnegie Endowment’s recent Africa Forum in June 2024, these sentiments were on full display by a number of African ambassadors.6

Unfortunately, African leaders also are quick to lament that America’s businesses have not been showing up, so African nations are forced to look elsewhere for their economic partnerships, most notably with China. Of course, mutually beneficial trade and investment is a two-way street. For their part, African leaders must commit to making the difficult reforms necessary to transform their economies into desirable destinations for American businesses. Currently, only two African countries, Mauritius and Botswana, are in the top forty in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom.7 Only one country, Seychelles, is in the top forty in the Freedom component of the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Index.8 Digitization, among other reforms, is a key driver of enabling transparency and establishing Africa as an economic destination.

U.S. diplomatic and foreign assistance attention and dollars should be pointed to countries that have made a clear, demonstrable commitment to a digital transformation, including AI technologies. The State Department, USAID, and other agencies engaging in U.S.-Africa policymaking and implementation should make cutting-edge digital technologies the cornerstone of their development and diplomatic architecture by integrating AI into every aspect of their work with the goal of fundamentally transitioning the U.S.-Africa relationship from an aid-based relationship to one rooted in commercial and economic cooperation, built upon a sixty-year foundation of shared values and trust. Without this commitment, China and other actors will continue to be the economic partners of choice for African nations, with disastrous impact to U.S. security and strategic interests.9

African nations’ diplomatic and economic relationships, particularly with China, are now rapidly evolving. In recent years, domestic economic pressures have slowed the proliferation of Chinese loans to African nations.10 Chinese private sector companies are now expected to take the lead.11 These companies are betting big on digital infrastructure to advance their Digital Silk Road ambitions as part of the broader Belt and Road Initiative.12 The window for the United States and other Western allies is open for now but will not remain open for long.

U.S. government agencies are large bureaucracies and often are slow to pivot, but private sector engagement has increasingly been recognized over the past twenty years, at least aspirationally, as good development policy. The last several presidential administrations have slowly started to turn the ship in this direction. In 2013, the Barack Obama administration launched the Power Africa initiative, which has continued through to the present day.13 In 2018, the Donald Trump administration announced the Prosper Africa initiative, which also has continued.14 Meanwhile, the Joe Biden administration has launched the Digital Transformation in Africa Initiative (DTA).15 Policy frameworks and infrastructure are beginning to emerge in the form of the State Department’s Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy, USAID’s Artificial Intelligence Action Plan, the recently released USAID Digital Policy, and President Biden’s Executive Order 13960.16 (Table 1 below summarizes the details on these initiatives.) Africa is beginning to develop its own strategic framework for a digital transformation through the African Union’s Digital Transformation Strategy.17 Although much more and speedy progress is needed, a handful of country-level AI strategies also are beginning to appear.18 The African Union Development Agency is in talks with several large U.S. tech firms to support a more fulsome AI strategy.19 These strategies are important, but a more crucial component will be a disciplined commitment to both resourcing and executing those strategies, driven by a well-trained workforce and knowledgeable leadership. Time is of the essence, given that AI is here now and is being adopted rapidly, with real-life implications well beyond theoretical concepts discussed in academic settings.

AI in Africa: Where Is It Today and Where Is It Going?

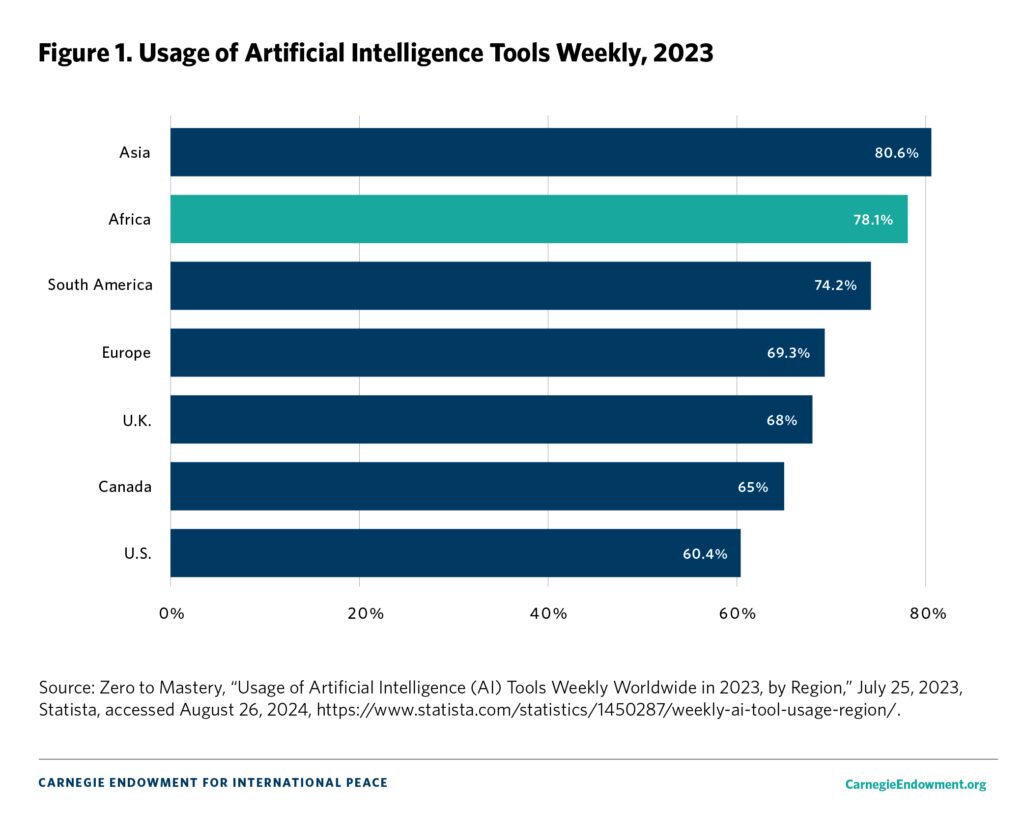

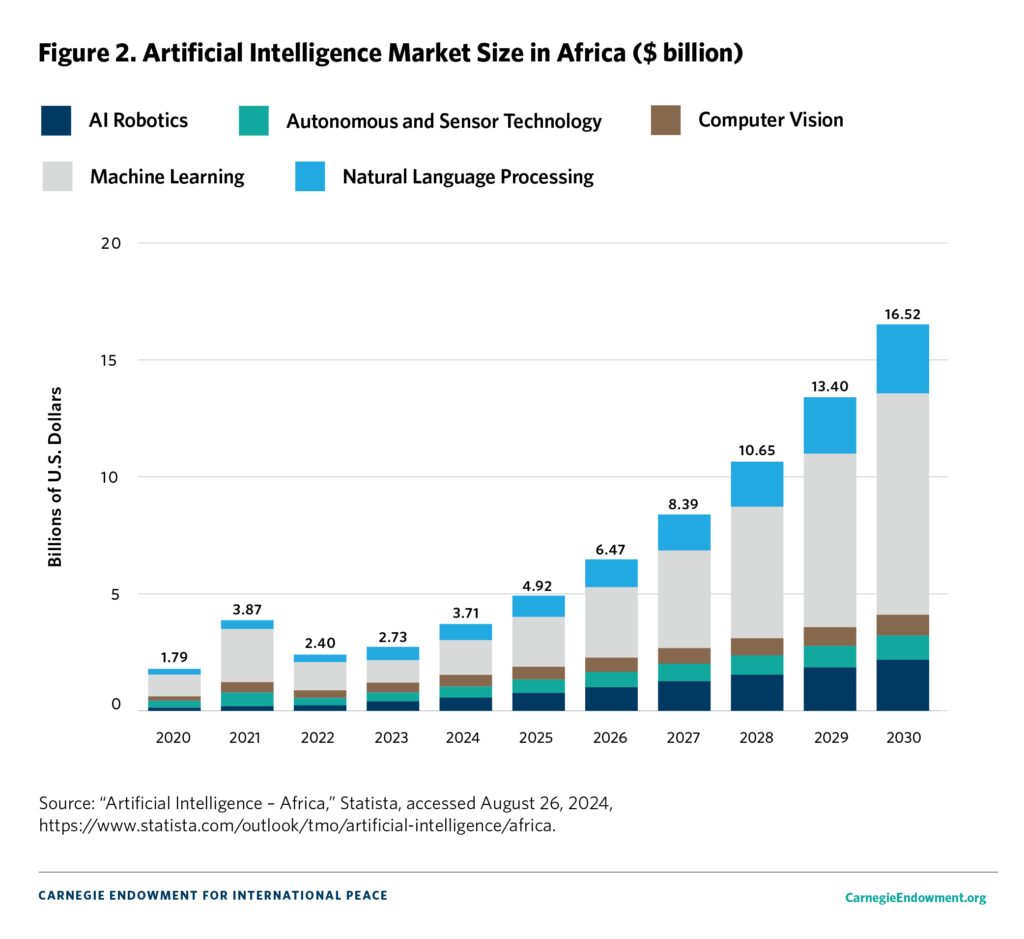

Africa’s demographic tsunami is well underway; its young population is already embracing AI technologies, and the technology’s usage is expected to soar over the next decade. By 2030, 42 percent of the world’s youth population will be Africans and 77 percent of Africa’s population is under age thirty-five.20 Their awareness and adoption of advanced technologies is already rivaling figures in Western populations. For example, 78 percent of Africans use AI tools at least weekly, compared to 69 percent in Europe and 60 percent in the United States (see figure 1). The direct AI market in Africa, currently at approximately $3 billion, is expected to grow by 28 to 30 percent annually over the next several years, reaching $16 to $18 billion by 2030 (see figure 2).21

Affordability, digital literacy, the usage gap,26 access to electricity, and gender disparities all continue to hinder broader access to the internet in Africa. Women in particular are affected, with 34 percent of African women enjoying internet access versus 46 percent of men. Geographic disparities for broadband speed and capacity also inhibit more advanced technologies from taking hold in Africa, particularly in rural areas. More than 84 percent of urban areas have upgraded networks to at least 4G compared to only 25 percent of rural areas, which still are largely dependent on 2G and 3G networks.27 AI systems often rely on large datasets to function effectively, and in many African countries data collection and management systems are underdeveloped. Good quality data, particularly in the health sector, may be scarce or unavailable.28

Although the digital divide is significant, Africa is not tethered to legacy infrastructure and often has been able to leapfrog technologies.29 Mobile phones, for instance, have proliferated in the absence of landline telephones.30 Likewise, peer-to-peer mobile payment platforms function in lieu of traditional banking services.31 These differences present an opportunity for key U.S. agencies—particularly the State Department, USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC),32 the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC),33 the Export-Import Bank, and the Department of Commerce—to engage on the African continent by partnering with American and African technology firms to advance development goals and shape the AI landscape. These agencies should prioritize support for digital infrastructure, telecommunications, and internet accessibility projects throughout Africa, both through direct programming and by bolstering advocacy efforts for American companies pursuing African public tender opportunities.

Risks Associated with AI for Coercive Purposes

Second, significant risks and legitimate concerns about AI remain issues to mitigate and navigate. The use of facial recognition and other biometric/digital ID technologies already are controversial for their potential misuse by authoritarian leaders limiting human rights, suppressing political opposition, and surveilling and censoring citizens.34 Yet another concern is the fact that these technologies have been known to have accuracy problems within African populations.35 Strategic and regulatory infrastructure also are lagging. Only seven African countries have developed AI strategies, compared with more than fifty countries around the world, plus the European Union (EU).36 Of the more than 700 AI policy framework initiatives implemented globally since 2017, only five have been from Africa.37 The United States, the EU, and other close allies have deep expertise that could be helpful to African partner countries and ensure a fair operating environment for all parties. This triangulating of partnerships with key allies offering specialized expertise could be highly attractive to African partners looking to pursue deeper commercial ties. Furthermore, it could assist in building the regulatory frameworks necessary to ensure the responsible proliferation of AI-powered technologies.

Bureaucratic Constraints

Last, the ways in which USAID and other government agencies engage partners and administer their appropriated resources must play a part in any transition to a technology-driven, economic-focused approach. The USAID and State Department workforces are overburdened by archaic procurement regulations, mountainous reporting requirements from partners, and heavily earmarked appropriations exacerbated by unnecessarily strict agency-level interpretations of earmark provisions well beyond congressional intent. These barriers result in a workforce reduced to pursuing a path of least resistance, which leads to a lack of incentive to innovate and, ultimately, to inertia.

Moreover, late appropriations, last-minute agency allocations, and pressure to move funding through the lengthy procurement process or at least park it in mechanisms before the two-year budget allocations expire often lead to large pipelines and limited pathways to engage new technology firms that are moving at breakneck speeds but have little or no U.S. government contracting experience. This restrictive environment ultimately results in the long-standing practice of awarding large contracts to large implementing partners to ensure that agency officials can get the money out the door.38 It also either inhibits partnerships with technology firms or constrains these partnerships to small-scale, disparate programs run by resource-starved innovation hubs, stuck in the corners of State Department or USAID headquarters and regarded by leadership as niche issues when they should be set front and center and implemented on a larger scale. Government leaders must understand and internalize that AI is no longer a niche issue and must be central to their strategic and policy development thought process.

Although these challenges and risks are formidable and must be recognized, mitigated, and addressed, they should not prevent or deter a movement to bring AI into the forefront of foreign assistance programming in Africa. Doing so would have disastrous geopolitical consequences for U.S. strategic interests in Africa. Conversely, overcoming these challenges and effectively harnessing the power of AI in Africa will drive the two-way trade and investment needed to propel the U.S.-Africa relationship into a more desirable economic, development, and diplomatic alliance.

How AI Can Transform U.S.-Africa Trade and Investment

AI has the potential to usher in a new era of U.S.-Africa relations through significantly increased and mutually beneficial trade and investment. A wide range of applications—including support for greater market intelligence, real-time data analytics, risk assessment and mitigation, and precision logistics and supply chain operations—will open the doors for AI to revolutionize the investment landscape in Africa.

AI can process vast amounts of information to identify market trends, consumer preferences, and emerging opportunities within various African economies, particularly in the financial sector.39 U.S. businesses can leverage these insights to tailor their strategies and offerings to the unique demands of African markets, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful ventures. AI can help in risk assessment by analyzing geopolitical, economic, and social factors, enabling investors to make informed decisions and mitigate potential risks associated with entering new African markets.

In addition, AI can streamline supply chain operations and logistics, which are critical components of trade, as well as improve global health initiatives vital to U.S. and African policy objectives for a healthy population and workforce. By optimizing routes, inventory management, and demand forecasting, AI can reduce costs and improve efficiency for companies engaged in U.S.-Africa trade. Predictive maintenance powered by AI can also ensure that machinery, transportation, and infrastructure operate smoothly, minimizing downtime and disruptions. Enhanced supply chain visibility through AI-powered tracking systems can foster greater transparency and trust between U.S. and African partners.

AI also can facilitate greater financial inclusion and access to capital in Africa, which is crucial for attracting U.S. investments. AI-driven fintech solutions can provide alternative credit scoring and lending platforms, helping small and medium-sized enterprises in Africa gain access to funding needed to grow.40 These new opportunities for credit can empower local businesses to expand and innovate, making them more attractive to foreign investors. Additionally, AI can enhance financial transaction security, reducing fraud risks, ensuring safer cross-border transactions in support of the African Union’s African Continental Free Trade Area,41 and facilitating digital trade, an important modernization to include in the African Growth and Opportunity Act reauthorization process.42 By fostering a more inclusive and secure financial ecosystem, AI can create a conducive environment for increased U.S.-Africa trade and investment, ultimately driving economic growth on both sides of the Atlantic.

Perhaps most importantly, AI and an accelerated digital transformation with an all in posture from the U.S. and African governments will create a more attractive trade and investment environment by changing the narrative around the ease of doing business in Africa in the eyes of American and international investors. All of these elements directly support the goals of the DTA, Biden’s executive order, the U.S.-Africa Strategy,43 Prosper Africa, and other interagency strategic planning documents.

To overcome the challenges and realize the benefits, leaders in Washington, as well as USAID mission directors and U.S. ambassadors in the field, must invest in their own education about AI technologies; understand the opportunities they present for bilateral cooperation; and steer resources toward advancing sound policy frameworks, digital infrastructure, and new partnerships. Senior leaders also need to work with congressional members and staffers to ensure mutual understanding of the intent of congressional earmarks and avoid misinterpretations. Lastly, procurement practices need to be reformed to encourage participation and engagement of nontraditional partners—that is, American and African technology firms that have impressive track records of success in their own industries but may not have pursued or participated in the government contracting industry.

Five Key Actions to the Successful Adoption of AI by Africa-Focused U.S. Government Agencies

Bring senior leaders up to speed. For U.S. government agencies to truly embrace AI and the digital transformation as a core driver of strategic priorities, government leaders in Washington and the field must have a strong command of where these technologies are, where they are going, and how they should shape a vision for our bilateral and multilateral partnerships. To achieve this, senior leaders will need to take the following steps.

Send a message to agency leadership that AI and the digital transformation is a central priority for delivering on U.S.-Africa diplomatic and development objectives and hold decisionmakers accountable for reflecting those priorities in both rhetoric and program design.

Increase access to leadership and elevate the voices of in-house technology experts through technology integration councils, chaired by department or agency leadership but powered by in-house experts, that track progress of technology usage in programs and initiatives. These forums are crucial for agency leadership to hear directly from subject-matter experts without the barriers created by hierarchical filters.

Secure real, tangible partnerships with American technology firms at the corporate level, codified by binding memorandums of understanding or letters of intent. Partnerships with the private sector are vital to success. Principal-level engagement will be critical to drive and demonstrate buy-in from both the government and the private sector.

Measure the performance of leadership (including mission directors, ambassadors, assistant secretaries, and assistant administrators) based on utilization and delivery of technology-based solutions to development and diplomatic challenges. Leaders respond to pressure from senior leaders providing a clear mandate and clear expectations. Programmatic decisions are (rightly) driven largely by leadership in the field, but these individuals need to know the priorities from Washington. Clear messaging that field leader performance will be evaluated based on programmatic integration of technology will accelerate action-oriented adoption of AI and other cutting-edge technologies into existing and new programs.

Invest in visiting technologist programs, such as the Tech Congress44 initiative (modified for executive branch leaders), and give these positions ready access to senior leaders to share the latest innovations and advice on how to take full advantage of their capabilities.Point development dollars toward shaping the AI/digital transformation landscape in Africa. USAID, the State Department, MCC, DFC, and other agencies have existing dollars, authorities, and mechanisms to prioritize AI strategies as a critical program initiative. With political will from agency and departmental senior leadership, program approval documents should require the program designers to include AI and digital transformation elements to secure agency approval. For example, every program approval process should include questions such as:

How does this program leverage AI and other digital technologies?

How does this program support the transition from an aid-based relationship to a U.S.-Africa partnership based on economic cooperation?

How does this program plan to engage African or U.S. technology firms?Prioritize AI and digital technology adoption into the selection of implementing partners. Once a program is approved and solicited, government contractors and partners are, by their nature, responsive to the government’s articulated priorities. Nevertheless, they need to be told what those priorities are. Contractors and partners historically have not innovated because they have not been required to do so to survive. In fact, the current practice is heavily weighted toward government contracting past performance credentials, which means that only those firms with long histories of managing U.S. government contracts, grants, and cooperative agreements are realistically competitive. These circumstances make partnerships with innovative technology firms, either African or American, nearly impossible through traditional procurement practices. Initiatives such as the New Partnerships Initiative are an attempt to address this problem, but the roots of inertia run deep.45 Even though a company may not have U.S. government contracting experience, this does not mean they cannot deliver results for the U.S. government. Therefore, the implementing partner selection criteria should transition away from being almost solely based on U.S. government contract experience and toward:

Demonstrable success in their respective area of expertise, rather than the government contracting industry

Demonstrable ability to integrate AI and digital technologies into various projects

Demonstrable capability to deliver results for their clients, regardless of sectorSupport accessibility and local-level AI capacity building and skills development. To be successful in shaping the AI landscape in Africa, USAID, the State Department, DFC, MCC, and other agencies will need to engage with, invest in, and support access to finance for local technology firms across Africa to build the capacity and skills of young, talented Africans. USAID has a long history of this work, but other agencies will also be critical to achieving success.46 USAID, the State Department, MCC, and DFC should:

Prioritize targeting African technology firms for DFC loan guarantee programs, which have proven effective in unlocking local capital for small businesses

Double or triple down on USAID programs, such as the USAID Digital Invest47 program, that are focused on accelerating new investments in digital products

Prioritize programs that expand technology and internet access across the continentTriangulate partnerships. Several U.S. allies are highly advanced in leveraging AI and other digital technologies that could complement American AI leadership in the healthcare, e-commerce, supply chain, and financial services sectors. Triangulated partnerships with allies with shared values and goals could leverage respective strengths, expand the tent, and offer strategic alternatives to China for the United States’ African partners. For example, the United States should consider working with:

British AI research institutions: Institutions such as the Alan Turing Institute48 and universities such as Oxford, Cambridge, and Imperial College London have partnered with African universities and research organizations, including the University of Nairobi, University of Cape Town, and University of Ghana, on AI-related projects in healthcare, education, and agriculture. The United States could be a force multiplier or gap filler in many of these partnerships.

Japan AI-powered robotics: The Tokyo Institute of Technology49 and other Japanese tech-based institutions and companies are increasingly active in Africa, particularly in Ghana and Ethiopia, in the areas of agriculture, emergency response, and medical innovation. All of these areas are key U.S. priorities ripe for collaboration, brokered via the Japan International Cooperation Agency.

German engineering and automated manufacturing technologies: Organizations such as Fraunhofer IGB50 collaborate with African institutions, including Stellenbosch University, on infrastructure projects related to renewable energy, water management, and agricultural technology.Conclusion

U.S. policymakers, African leaders, and the private sector all desire to modernize the U.S.-Africa relationship in ways that deliver mutually beneficial economic cooperation. AI and other cutting-edge technologies offer the promise of a vehicle for such a transformation. Centering U.S. diplomatic and development priorities around advancing AI-powered technologies and the broader digital transformation in Africa will bring about the change all parties want to see. However, it will require the political will, a commitment to changing the status quo, and a bold vision for the future to overcome the formidable challenges. The stakes are high and the clock is ticking.