Key Takeaways:

- Mali. JNIM attacked the main military air base and a gendarmerie base in Bamako, its first attacks in the capital since 2015. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM) likely conducted the attacks to undermine the legitimacy of the Malian junta and reduce both elite and popular support for the junta. JNIM has significantly strengthened its support zones in southern Mali since 2022 and is likely using these areas to support more sophisticated and frequent activity in and around the capital.

- Chad. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán repeated his intention to follow through on delayed plans to deploy 200 Hungarian troops to Chad to help stop migration and improve counterterrorism efforts. Hungary’s objectives are publicly aligned with the EU and are similar to the policies of other anti-immigration EU countries, such as Italy, that have sought to increase their role in the Sahel as France’s influence wanes. Hungary may also have alternative or secondary aims to offer regime support in exchange for economic benefits. Hungary giving greater priority to regime security and economic objectives over migration concerns would increase its alignment with Russia and create opportunities for cooperation in the Sahel. However, Hungary’s efforts have no explicit link to Russia, and Hungary and Russia are likely not explicitly coordinating their activity in the region.

- Horn of Africa. The Ethiopia-Somalia dispute is threatening to spark proxy conflicts in both countries between local actors and the federal governments. Tensions are growing between the Somali Federal Government (SFG) and the regional South West State government over the SFG’s decision to replace Ethiopian forces with Egyptian forces, which may result in a military conflict. The SFG has also threatened to support ethno-nationalist insurgents in Ethiopia, which could exacerbate festering conflicts between the Ethiopian government and multiple ethno-nationalist militants in Ethiopia.

- Assessments:

Mali

JNIM attacked the main military air base and a gendarmerie base in Bamako, its first attacks in the capital since 2015. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM) conducted two nearly simultaneous attacks targeting a gendarmerie school and the main Malian air base, Senou Air Base, on the morning of September 17.[1] French media reported that one group of attackers first hit the school, which also houses elite gendarmerie units, to distract security forces from the main attack at the air base.[2] JNIM claimed that the attack killed hundreds of soldiers, destroyed six military aircraft, and disabled four other aircraft.[3] An anonymous Malian officer told French outlet Le Monde that the attack on the gendarmerie school alone killed 60 people.[4]

JNIM likely conducted the attacks to undermine the legitimacy of the Malian junta and reduce both elite and popular support for the junta. The Malian junta came to power promising to improve security and has pushed a narrative in the capital that it has done so despite the worsening insurgency in central and southern Mali.[5] The first attack in the capital in nearly a decade directly undermines this narrative. JNIM also targeted two “hard” military targets, indicating an explicit effort to intimidate the junta and avoid alienating civilians. JNIM even published footage showing militants burning the presidential plane, drawing an explicit link to the junta.[6] This attack pattern differs from the group’s previous attacks in Bamako, which targeted soft civilian targets like luxury hotels and resorts.[7]

JNIM also likely targeted Senou Air Base to support its narrative that it is a protector from, and avenger of, the human rights abuses inflicted by Malian and Russian forces. Russian forces and Malian drones are both stationed at the Senou Air Base.[8] JNIM has repeatedly condemned Russian forces operating in Mali for massacring civilians and sworn to avenge their victims.[9] The group has also criticized Malian drone strikes that have killed civilians and blasted Turkey, which supplies the Bayraktar TB2 drones that the Malian army uses.[10] JNIM explicitly noted that it inflicted losses on the “Wagner mercenaries” at the air base, destroyed a drone, and avenged “the hundreds of massacres and slaughters perpetrated by this junta and its Russian allies against our Muslim people.”[11]

JNIM likely symbolically timed the attack to embarrass and undermine the Malian junta and its regional allies in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), Burkina Faso and Niger. The attack was the day after the first anniversary of the creation of the AES, on September 16, and five days before Mali’s independence day, on September 22.[12] The foreign ministers of the AES countries were meeting in Bamako on the day of the attack to discuss ways to better coordinate diplomatic activity among the alliance.[13] The AES has repeatedly criticized other regional bodies for not doing enough to combat regional security issues like the JNIM insurgency and increased efforts in 2024 to undertake joint security operations to counter JNIM in all three countries.[14]

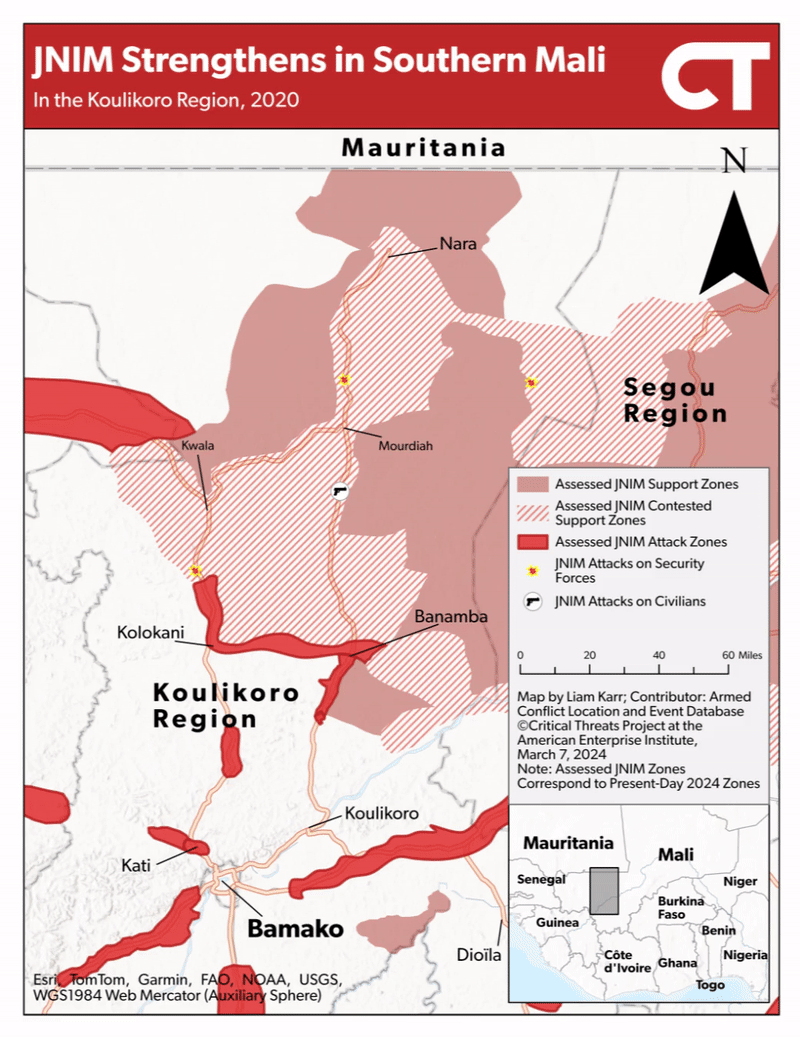

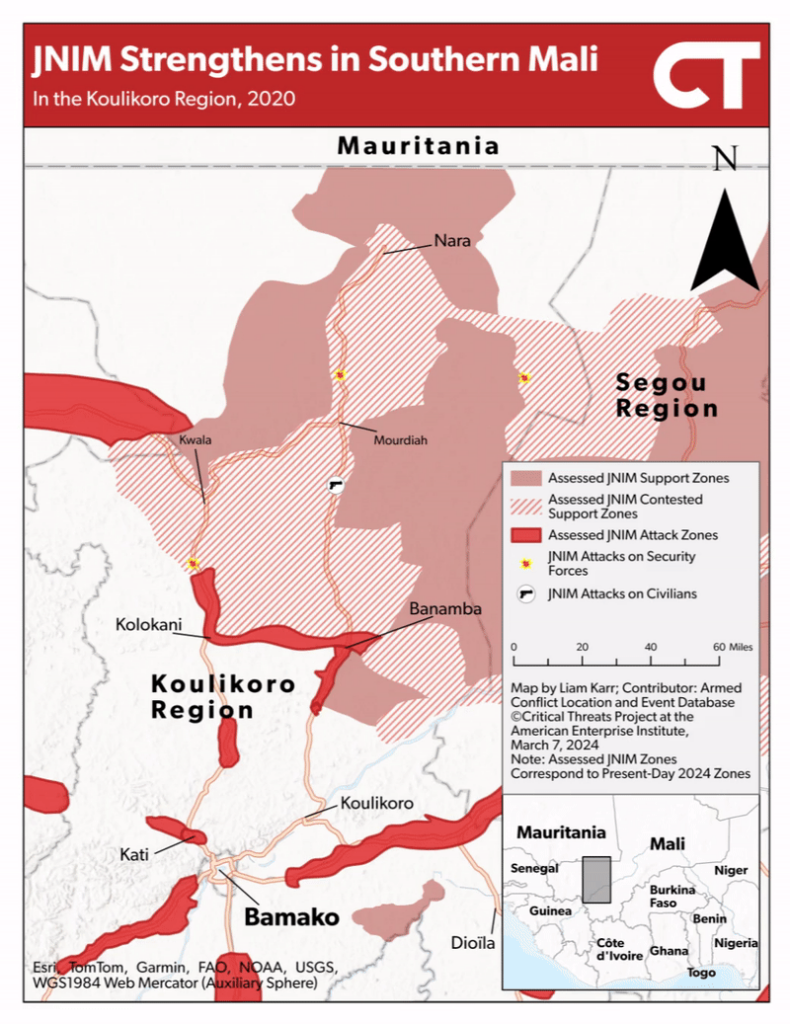

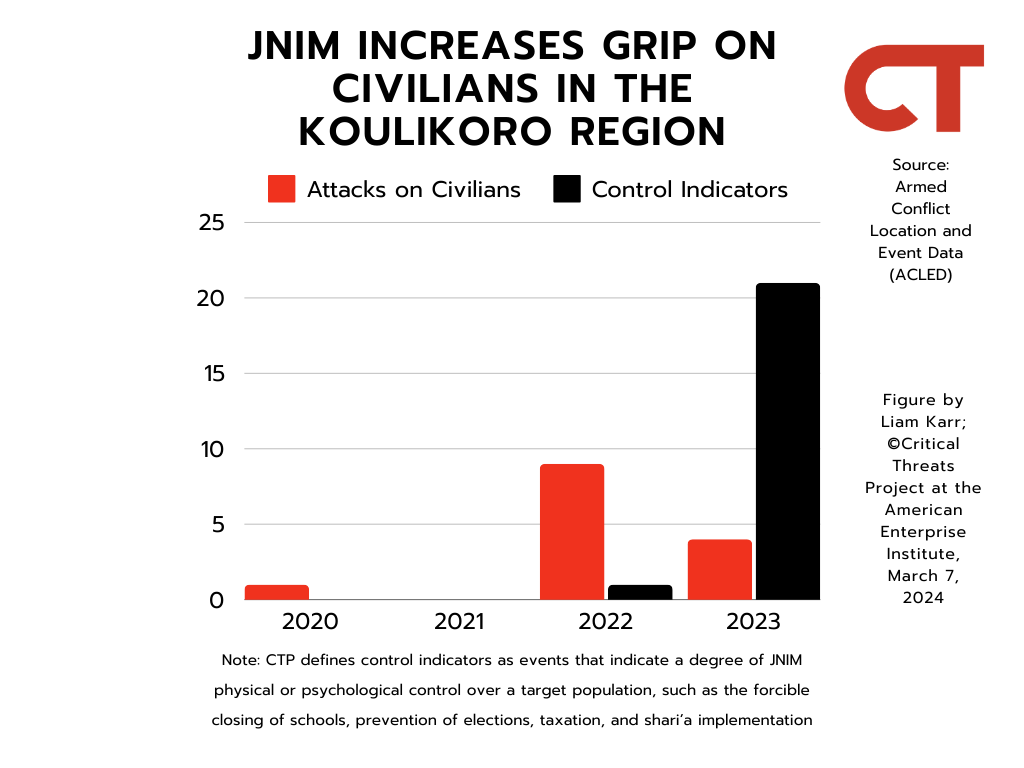

JNIM has significantly strengthened its support zones in southern Mali since 2022 and is likely using these areas to support more sophisticated and frequent activity in and around the capital. JNIM established support zones in the northern half of the Koulikoro region in 2023 and 2024. JNIM shifted its activity in the Banamba and Nara districts (officially called cercles in Mali) from targeting security forces to coercive attacks on civilians in 2022.[15] The Armed Conflict Location and Event Database project recorded growing reports of control indicators around both districts in 2023, such as JNIM closing schools, preventing local elections, taxing civilians, and enforcing localized shari’a agreements in both districts.[16] Local and international sources have also reported that the group is besieging several key towns in the area and controls the RN4 road that runs south towards Bamako from Nara.[17] CTP previously assessed that the group in 2024 used these support zones to conduct its first suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device attacks in the Koulikoro region since 2022 and would use these areas to increase the rate and sophistication of its attacks around the Malian capital.[18]

Figure 1. JNIM Strengthens in Southern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Figure 2. JNIM Increases Grip on Civilians in the Koulikoro Region

Note: CTP defines control indicators as events that indicate a degree of JNIM physical or psychological control over a target population, such as the forcible closing of schools, prevention of elections, taxation, or shari’a law implementation.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

JNIM has increased the rate and sophistication of attacks on roadways around Bamako in 2023, demonstrating the intent and growing capability to attack near the capital. [19] JNIM waged an offensive targeting the roads surrounding Bamako in the first half of 2023, conducting at least 17 attacks within 70 miles of the capital between January and July. [20] CTP previously assessed that JNIM aimed to disrupt lines of communication in southern Mali and discredit the Malian junta based on JNIM primarily targeting security forces and framing the attacks as a challenge to the junta’s authority.[21] The group also launched a complex attack involving two suicide VBIEDs targeting military installations at Kati—10 miles from Bamako—in 2022, initially demonstrating its capability to carry out more sophisticated attacks around Bamako for the first time since 2015.[22]

Chad

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán repeated his intention to follow through on delayed plans to deploy 200 Hungarian troops to Chad to help stop migration and improve counterterrorism efforts. Orban affirmed the plans after meeting with Chadian President Mahamat Deby in Budapest from September 7 to 9.[23] The Hungarian defense minister initially announced in November 2023 plans to deploy troops in the spring of 2024 to help Chadian forces stop migration, improve counterterrorism efforts, and help implement humanitarian and economic assistance programs.[24] Hungary also opened a humanitarian center and diplomatic mission in the Chadian capital and signed agriculture and education agreements with Chad over the last year.[25]

The mission has faced delays due to internal challenges and pushback in Chad and Hungary. French media reported in March that the mission had been delayed due to recruitment challenges.[26] Several of Deby’s close advisors are opposed to the deployment.[27] Opposition groups in Hungary have also called the deployment “dangerous and wasteful” and accused Orban of nepotism due to the heavy role of his son, Gaspar Orbán, in negotiations surrounding the partnership.[28]

Hungary’s objectives are publicly aligned with the EU and are similar to the policies of other anti-immigration EU countries, such as Italy, that have sought to increase their role in the Sahel as France’s influence wanes. Hungary has already supported non-military development programs in Chad and other African countries through its Hungary Helps program, which partially aims to reduce emigration to Europe.[29] Hungarian officials have framed the deployment as part of this effort and in line with European interests to stabilize the region. However, Hungary’s impact on migration in Chad will be more limited given migration numbers in Chad are much lower than countries like Niger and Sudan.[30]

Italy has remained engaged in countries like Niger due to its migration concerns. At least 250 Italian military personnel have remained in Niger to train and advise Nigerien forces as part of its Bilateral Support Mission to Niger.[31] The mission began in 2019 to support border surveillance activities to control migrant flows.[32] Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has also increased outreach to African countries to increase cooperation to stem migration.[33]

The EU and France have voiced support for Hungary’s plans. An EU spokesperson “welcomed” Hungary’s initiative and encouraged more international partners to work with Chad to address its challenges.[34] French and Hungarian forces have discussed cooperating on medical services in Chad, and French media reported that French President Emmanuel Macron has remained in contact with Orbán on the issue despite their strained relationship.[35]

Hungary may also have alternative or secondary aims to offer regime support in exchange for economic benefits. The Poland-based investigative outlet VSquare cited a Hungarian government source claiming that Gaspar Orbán said the mission would provide economic opportunities, such as deals on oil and uranium extraction.[36] VSquare also reported that Hungarian and central European government officials said Gaspar Orbán has also discussed establishing a civilian and military intelligence gathering apparatus in Chad.[37] This capability could be used to support a wide range of activities, including regime security functions.

CTP has previously assessed that Chad would be interested in such an arrangement to strengthen regime security and respond to internal pressure to distance itself from the West. Deby faces internal tensions with Chadian elites related to his handling of the civil war in neighboring Sudan. Deby decided to cooperate with the United Arab Emirates by letting it use an airport in eastern Chad to support Sudan’s paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in exchange for financial aid.[38] This move alienated elites from the eastern Sudan that view the RSF as a threat due to a history of cross-border ethnic tensions and violence involving militia groups that now compose the RSF.[39] American experts on African politics have warned that these tensions could result in an elite coup.[40] Domestic opposition groups have also fomented protests including thousands of people on multiple occasions since 2021 to call for the departure of French troops in the country, creating a potential impetus for a non-Western security partner.[41]

Hungary giving greater priority to regime security and economic objectives over migration concerns would increase its alignment with Russia and create opportunities for cooperation in the Sahel. Russia has pursued a similar policy of offering its authoritarian partners a “regime survival package,” in which it provides regime support in exchange for preferential economic deals.[42] Russia has also increased its outreach to Chad throughout 2024, including a meeting between Putin and Deby in Moscow in January.[43] CTP has previously assessed that Russia likely seeks to increase its influence in Chad to undermine—and eventually remove—the West from the Sahel region, support Russian operations in neighboring theaters, and mitigate the effects of sanctions for its war in Ukraine.[44] Hungary and Russia have also enjoyed warming ties outside of the Sahel. The two have maintained a strong relationship since Russian invaded Ukraine in 2022, and Orbán has strong personal ties to Putin and similar nationalistic and anti-Western views despite Hungary’s EU and NATO membership.[45] Oil production and uranium mining would be areas of mutual benefit given Hungary’s domestic capacity to use these resources are dependent on Russian provide resources.[46]

However, Hungary’s efforts have no explicit link to Russia, and Hungary and Russia are likely not explicitly coordinating their activity in the Sahel. First, Hungary and Russia have different interests in trans-Saharan migration challenges. Hungary has repeatedly emphasized that it wants to cut down on trans-Saharan migration to Europe, while the EU has repeatedly warned that Russia seeks to weaponize it as it has in other areas of the world.[47]

Hungary’s interests in the Sahel also pre-date Russia replacing France as the main partner in the Sahel. Orbán initially tried to participate in the now-defunct EU Task Force Takuba, which was supposed to support French troops in Mali before the junta kicked out Western forces in favor of Russian mercenaries, in 2022.[48] Orban then reached out to now-deposed Nigerien Prime Minister Mohamed Bazoum, who was a key ally of both France and the United States before a pro-Russian junta overthrew Bazoum in a coup in July 2023.[49]

Horn of Africa

The Ethiopia-Somalia dispute is threatening to spark proxy conflicts in both countries between local actors and the federal governments. Relations between Ethiopia and Somalia have rapidly worsened since Ethiopia signed an agreement with Somaliland in January. The deal involved Ethiopia receiving land for a potential civilian- or military-use port on the Somaliland coast that would grant Ethiopia Red Sea access via the Bab al Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen in exchange for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[50] The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty and threatened to “retaliate” if Ethiopia followed through.[51]

Tensions are growing between the Somali Federal SFG and the regional SWS government over the SFG’s decision to replace Ethiopian forces with Egyptian forces. SFG officials announced in June that the SFG plans to expel Ethiopian forces from Somalia after the conclusion of the current African Union (AU) mission, at the end of 2024, unless Ethiopia revokes its port deal with Somaliland.[52] The SFG has since reached agreements with Egypt to fill Ethiopia’s role by contributing to the new AU peacekeeping mission scheduled to begin in 2025 and immediately deploy forces to help train the Somali National Army.[53] South West State (SWS) officials have repeatedly rejected the SFG’s plans and said they preferred to keep working with Ethiopian forces, which have been present in Somalia as part of AU peacekeeping missions and bilateral arrangements with the SFG since 2014.[54]

The SFG has already begun retaliating against local politicians speaking out in favor of Ethiopia, marginalizing those communities and increasing the risk of an internal conflict. The Somali parliament began efforts to pass a law to strip immunity from 25 SWS members of parliament in early September.[55] The SFG allegedly canceled several flights between Mogadishu and the SWS’s de facto political capital, Baidoa, on September 17, as SWS members of parliament were planning to travel to Baidoa to meet with regional leaders.[56]

The SFG is trying to reach a diplomatic solution but may also use military force. Somali Prime Minister Hamza Abdi Barre and National Intelligence and Security Agency Director Abdullahi Mohamed Ali traveled to Baidoa to discuss the issue with regional SWS lawmakers on September 11.[57] Somalia media also reported that Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud is meeting with interlocutors and may visit Baidoa to meet with SWS President Abdiaziz Laftagareen.[58]

Somali media reported that the SFG deployed special forces to SWS, which would be a clear precursor to infighting between the SFG and the regional government. A senior regional official and local journalist denied Somali media reports that the SFG deployed Turkish-trained special Haramcad special police and Gorgor commandos to the SWS district capital, Barawe, on September 16.[59] The SFG typically deploys special forces during conflicts with regional governments because state security forces and many of the Somali National Army soldiers in the area usually side with the local governments based on shared clan ties.[60]

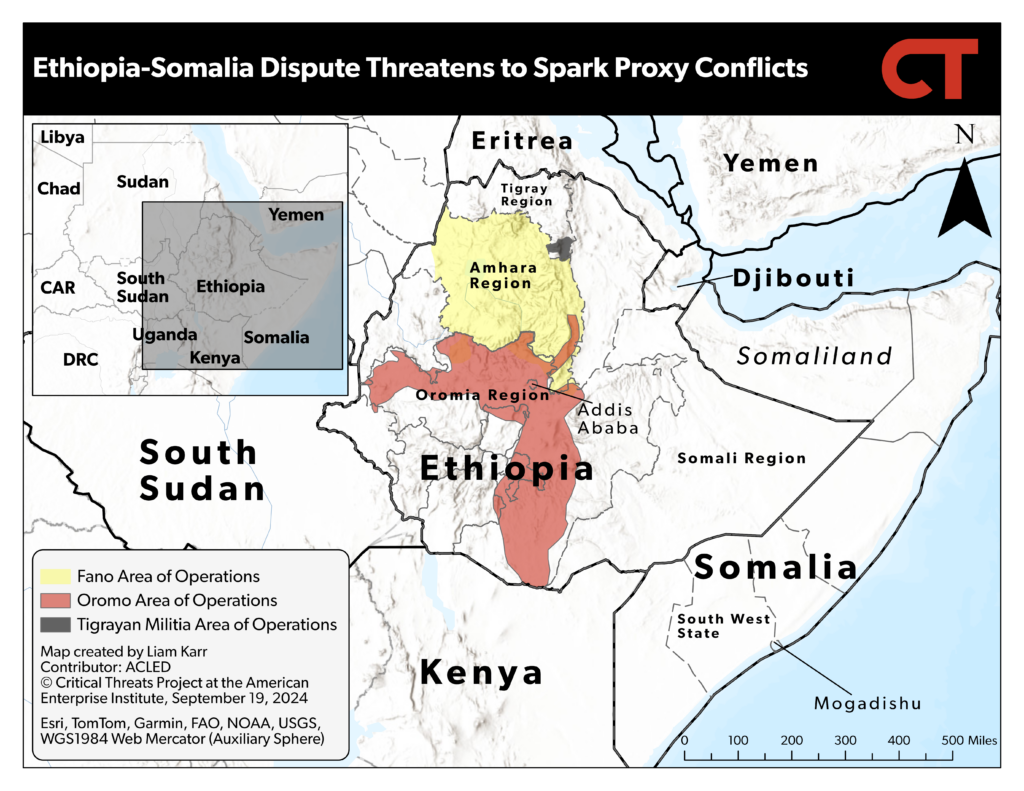

Figure 3. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute Threatens to Spark Proxy Conflicts

Note: “CAR” is the Central African Republic. “DRC” is the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The SFG has also threatened to support ethno-nationalist insurgents in Ethiopia, which could exacerbate festering ethnic conflicts in Ethiopia. Somali Foreign Minister Ahmed Moalim Fiqi said in mid-September that the SFG would consider establishing contact with rebels if Ethiopia followed through on its agreement with Somaliland but that the crisis had not yet “reached that stage.”[61] Increased internal violence in Africa’s second most populous country would have far-reaching economic, humanitarian, political, and security ramifications for the Horn of Africa.

Ethiopia is facing several ethno-nationalist insurgencies across the country. A loose collection of decentralized Amhara militias known as Fano have been waging an insurgency against the federal government in northern Ethiopia since August 2023.[62] Fano launched several offensives in September 2024 that captured several key points near Gondar, Ethiopia’s second-largest city, and other towns along the border with Sudan.[63] The Fano insurgency overlaps with a conflict between federal forces, and Oromo insurgents that also sometimes fight Fano in central Ethiopia.[64] The federal and regional governments in Tigray are also still working to implement the 2022 peace agreement that ended the Tigray war, which has caused internal disputes amongst Tigrayan leaders and clashes between Amhara and Tigrayan militias over disputed areas.[65]

The SFG could also exploit growing tensions between the Ethiopian government and former Somali insurgents in the Somali Region in eastern Ethiopia. The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) abandoned its armed struggle for Somali self-determination and pursued political power after a 2018 peace deal ended their over 30-year insurgency.[66] However, the group released a statement on September 17 warning that the Ethiopian government was taking inflammatory actions in response to the Ethiopia-Somalia dispute that was jeopardizing and violating the peace deal.[67] The ONLF accused the federal government of discrimination against Somali citizens, such as forcing them to deny their ethnic identity on television, planning to erase Somali identity from the state name and flag, and imposing martial law on the region. The ONLF would be the easiest group for the SFG to support if the ONLF resumed its insurgency due to their shared Somali ethnic identity and proximity across the Ethiopia-Somalia border.