The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

China. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) announced the highest total investment through the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) since the peak of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the subsequent COVID-19 pandemic as it discussed plans to continue diversifying cooperation in Africa beyond hard-infrastructure BRI projects. Many of the new agreements and funding plans from FOCAC 2024 are areas of emphasis in its 2021 Global Development Initiative, including green energy and tech, food and health development, and governance and military cooperation. The PRC did not announce crucial debt relief or restructuring but did follow through on other goals of African partners, such as better access to Chinese markets and promises to fund stalled infrastructure projects. The PRC used the summit to advance its narrative as an alternative to the West and diplomatically signal its view of Africa and African countries as pivotal to its long-term strategic vision to counter the US-led international system.

Mali. Malian and Russian troops are preparing to relaunch their offensive in northern Mali along the Algerian border for the first time since Tuareg militants defeated them in the area in July. Security forces face several capacity and capability challenges to clear and hold the Algerian border and other remote areas of northern Mali. Russian military commentators framing the Russian units participating in the offensive as part of the Russian Ministry of Defense–linked Africa Corps may indicate that the Ministry of Defense has consolidated greater control over the Russian presence in Mali.

Assessments:

China

The PRC announced the highest total investment through the FOCAC since the peak of its BRI and the subsequent COVID-19 pandemic as it discussed plans to continue diversifying cooperation in Africa beyond hard-infrastructure BRI projects. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) launched the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in 2000 and has held a FOCAC meeting every three years.[1] The FOCAC has become a key piece of the PRC’s Africa strategy, through which it sets priorities and the framework for its economic, political, and security goals on the continent.[2]

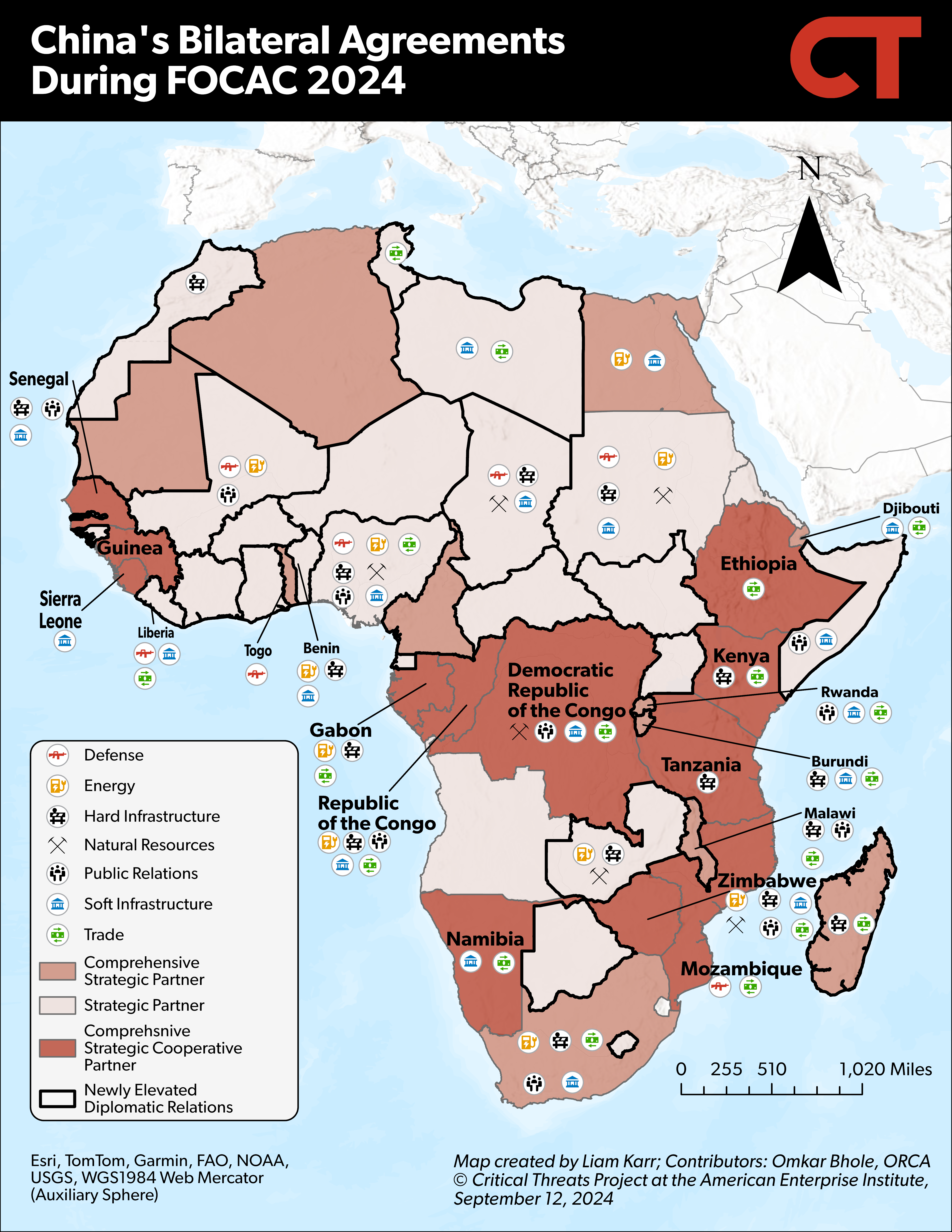

The PRC pledged to invest nearly $50.7 billion in financing for Africa at the 2024 FOCAC as part of a 10-point initiative.[3] The total is $10 billion short of the largest FOCAC investment plans at the peak of the BRI, in 2015 and 2018, but $10 billion more than FOCAC 2021.[4] The PRC plans to disburse nearly $30 billion of the assistance through credit lines, more than triple the credit it granted at the previous conference, in 2021.[5] The 2024 credit lines also differ from the substantial loans that the PRC granted in 2015 and 2018. Chinese firms plan to invest another $10 billion, equal to the amount promised at the 2021 FOCAC.[6] The remaining roughly $10 billion consists of smaller amounts provided through other unspecified aid.

Figure 1. Chinese Investment Pledges During the FOCAC: 2006 to 2024

Source: Liam Karr; Alex He; Center for International Governance Innovation

The PRC continued its yearslong effort to make its economic engagement in Africa more sustainable and profitable by expanding its investment portfolio in line with its Global Development Initiative (GDI). Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leader Xi Jinping announced the PRC’s revamped strategy—the GDI—in September 2021 and made it a focus at the previous FOCAC, in November 2021.[7] The GDI emphasizes investment in projects that promote “software for development” to address issues like poverty, food insecurity, pandemic responses, development financing, climate change mitigation and green tech, industrialization, the digital economy, and connectivity.[8]

The CCP aims for the GDI to be more integrated across CCP strategy and in its international outreach strategy. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs heads GDI-related frameworks, aiming to address issues with various institutions and actors failing to coordinate a unified strategy for the BRI.[9] The PRC has worked to make the GDI a multilateral program through cooperation with the UN Development Program and establishing other multilateral platforms surrounding the GDI.[10] Xi has also said the GDI explicitly supports the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.[11]

Multiple factors contributed to the policy shift to deprioritize the BRI in favor of the new GDI. First, the COVID-19 pandemic naturally stunted the BRI’s momentum. By mid-2020, many projects were on hold, with 20 percent of projects “seriously affected” by COVID fallout, causing BRI-related investments to fall from $60.5 billion in 2020 to $56.5 billion in 2021.[12] The CCP was also facing more economic pressure at home. Growing debt levels began constraining the PRC’s financing abilities more than when it launched the BRI in 2013, and the CCP had issued its 14th Five-Year Plan calling for more sustainable and financially profitable investments.[13] The West also developed its own infrastructure initiatives to rival the BRI, while African countries and the PRC began looking for more multilateral financing solutions as African debt—including to the PRC—continued to balloon.[14]

Many of the new agreements and funding plans from FOCAC 2024 are on GDI areas of emphasis, including green energy and tech, food and health development, and governance and military cooperation. The PRC pledged $140 million of aid for food security and another $140 million for defense.[15] The CCP announced plans to fund 30 green energy projects, 30 joint laboratories to collaborate on satellite and space technology, 30 “interconnectivity” projects, 25 research centers, and 20 “digitization” projects.[16] The PRC also plans to launch 20 health initiatives covering malaria treatment, pharmaceutical production, and epidemic responses across the continent.[17]

The PRC is emphasizing person-to-person exchanges as part of its initiatives to build human network ties across the continent. The PRC will send 500 agricultural experts and 2,000 medical staff to Africa as part of its programming and train 6,000 military personnel and 1,000 law enforcement officers in Africa.[18] The CCP also plans to invite young military officers and 1,000 government officials to the PRC to learn about relevant governance and military tactics.[19]

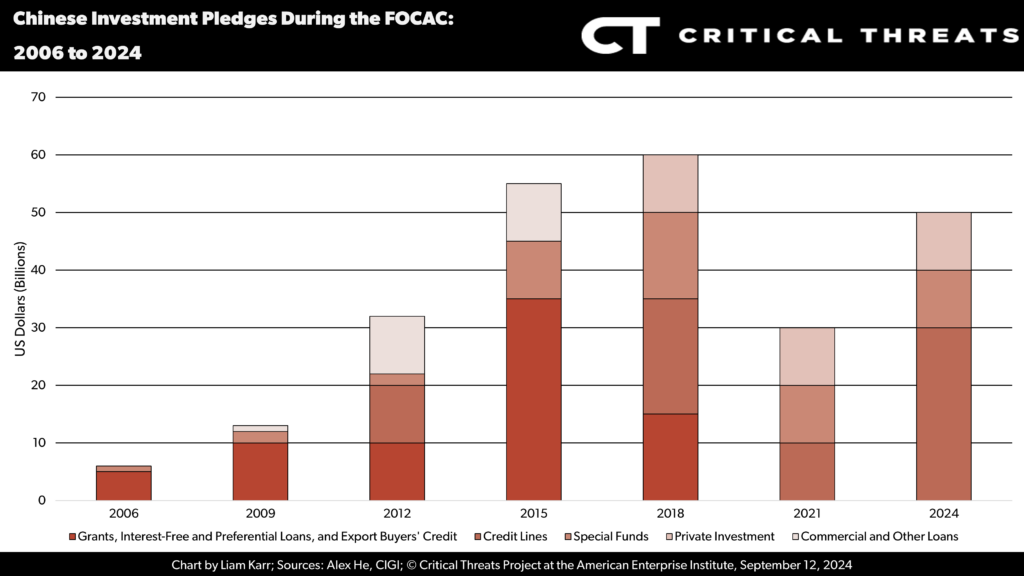

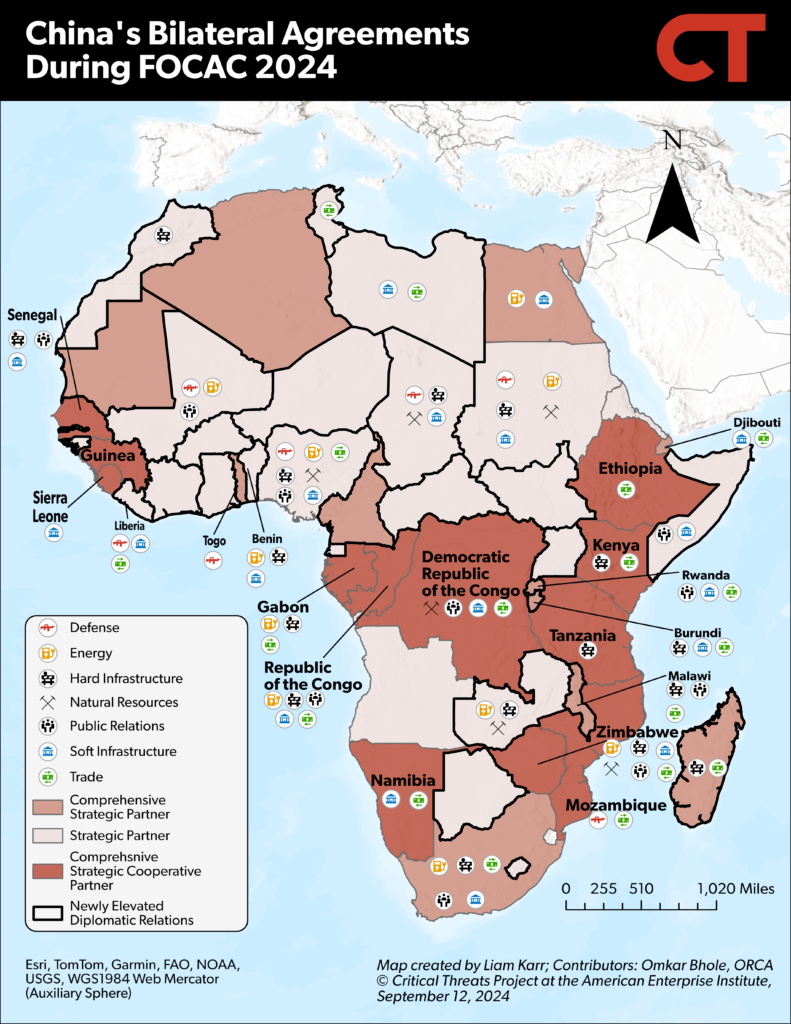

Figure 2. China’s Bilateral Agreements During FOCAC 2024

Note: Soft infrastructure includes agriculture, education, health, local economic development, tech, and telecommunications projects. Trade includes currency swap and export agreements. Public relations includes cultural exchange and media sharing agreements.

Source: Liam Karr, Omkar Bhole, Organisation for Research on China and Asia.

The PRC did not announce crucial debt relief or restructuring but did follow through on other asks from its African partners, such as better access to Chinese markets and promises to fund stalled infrastructure projects. The PRC’s role as a leading lender to African countries makes it a key player in addressing Africa’s debt crisis. Chinese lenders accounted for nearly 12 percent of Africa’s total external debt of $697 billion by the end of 2020.[20] The PRC is not solely responsible for causing African debt distress, and analysts have cast severe doubt on any notions of intentional Chinese “debt-trap diplomacy.”[21] However, many African states have made efforts to gain forgiveness or restructuring of their Chinese loans.[22]

Critics have taken issue with certain predatory aspects of the Chinese lending model that undermine recipient countries’ long-term economic health. Chinese loans often prohibit collective restructuring, include confidentiality causes, and suppress local industries by mandating that Chinese state-owned enterprises be the primary contractors for related projects.[23] The PRC also coordinates its lending to Africa around politically oriented events like FOCAC, leading to economically irresponsible lending to small countries for political purposes.[24]

The PRC announced significant infrastructure investments that aim to finish stalled BRI projects and launch some new projects. The PRC’s shift away from the BRI that began in 2019 led to decreased lending to African countries, leaving several BRI projects stalled and incomplete.[25] These delays exacerbated affected countries’ struggles to integrate and grow their economies to address their debt issues.[26] The PRC agreed to fund stalled railway projects in Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia and another regional highway in Kenya.[27]

Figure 3. China’s Hard Infrastructure Deals

Source: Liam Karr.

The CCP has prioritized “small and beautiful” projects over major infrastructure undertakings as part of the BRI since giving greater priority to the GDI. The PRC announced plans for 1,000 of these “small and beautiful” projects during the forum. It explicitly framed a $281 million rural road construction development in Kenya as one of these projects.[28] Several other countries signed infrastructure deals that are presumably part of this effort, including airport construction in Chad, high-speed rail networks in Morocco, and modernizing airports and seaports in Sudan.[29]

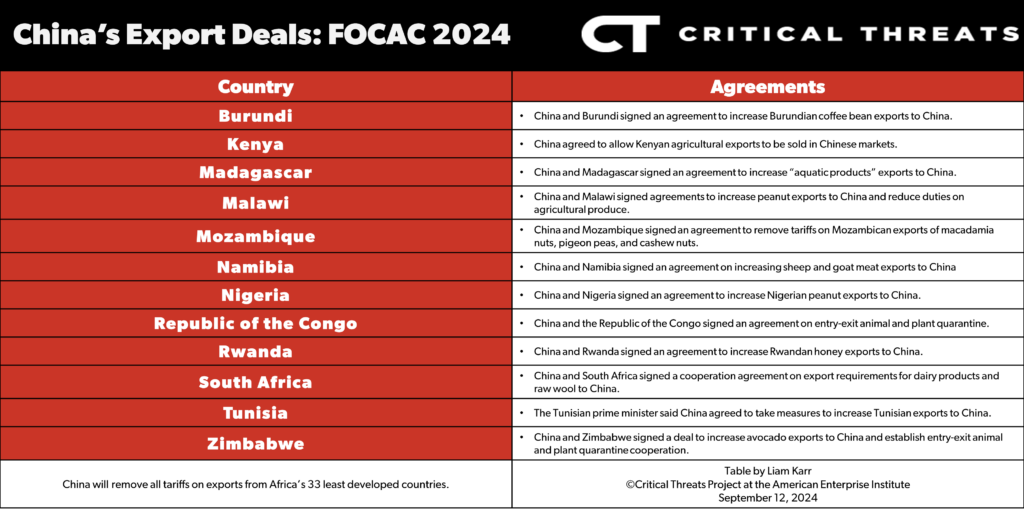

The CCP also launched several bilateral and multilateral initiatives to make it easier for African countries to export goods to Chinese markets. The PRC removed all tariffs on all goods from the 33 least developed countries in Africa.[30] The tariffs have contributed to a significant trade deficit between the PRC and sub-Saharan Africa in recent years.[31] The PRC also signed separate bilateral agreements with 12 African countries that will make it easier for them to export various products to the PRC.[32]

Figure 4. China’s Export Deals

Source: Liam Karr. Individual sourcing available by request.

The CCP used the summit to advance its narrative as an alternative to the West and diplomatically signal its view of Africa and African countries as pivotal to its long-term strategic vision to counter the US-led international system. CCP officials repeatedly described “the great suffering” of developing countries under Western modernization.[33] Xi and other CCP officials regularly referred to Africa and the PRC’s “shared future” outside the US-led international order.[34] Xi also said in a summit speech that “the China-Africa relationship is now at its best in history.”[35]

The PRC upgraded diplomatic ties with all African countries to at least the strategic level, indicating Africa’s importance in the PRC’s strategic priorities.[36] The PRC claims to have a non-alliance policy and therefore doesn’t have any official alliances and puts a heavy emphasis on bilateral partnerships. The strategic level is the third-highest of the PRC’s six general bilateral ties categories.[37] The PRC uses these six groupings to signal its strategic priorities and perceptions of various countries.[38] There is no precise definition for the categories, and partnerships do not always equate to preferential treatment.

The PRC also upgraded at least eight countries to the comprehensive strategic partner level, the second-highest category. Burundi, Cameroon, Djibouti, Madagascar, Mauritania, Rwanda, Senegal, and Togo all received the upgrade. [39] Cameroon, Madagascar, and Mauritania are the only countries of these eight to not announce additional follow-up agreements with the PRC. The PRC establishes comprehensive strategic partners with countries in regions it deems crucial to its strategic goals so it can establish channels to facilitate cooperation and coordination across multiple sectors and on regional and international affairs.[40] Several EU and South American countries are also considered comprehensive strategic partners.[41]

At least 12 African countries were already comprehensive strategic cooperative partners—the highest partnership grouping outside of a handful of special accolades.[42] Comprehensive strategic cooperative partnerships involve a greater emphasis on the full pursuit of cooperation and development.[43] Russia and Pakistan are the only two countries outside Africa and Southeast Asia that have variations of the comprehensive strategic cooperative partner title.[44]

The PRC further emphasized its perception of Africa as crucial to its strategic vision with a declaration that frames Africa as an “all-weather” partner for the “new era.” The PRC foreign ministry spokesperson announced that all participating countries agreed on the “Beijing Declaration on Building an All-Weather China-Africa Community with a Shared Future in the New Era.”[45] The PRC had used framing like “all-weather” and “new era” to define only its uniquely close partnerships with Russia and Pakistan.[46] The “all-weather” framing indicates the PRC’s intentions to maintain long-term ties regardless of global shifts. The “new era” framing is a clear challenge to the US-led international system.

The PRC also undertook multilateral and bilateral initiatives to lessen dependency on the US dollar. The PRC plans to disburse all its FOCAC funding using the Chinese yuan instead of the dollar for the first time.[47] The PRC also signed currency swap agreements with Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Mauritania.[48] Ethiopia and Nigeria are the continent’s fifth- and fourth-largest economies, respectively.[49] Currency swaps reduce dependence on the US dollar by strengthening non-dollar foreign reserves and enable trading in other national currencies.

Mali

Malian and Russian troops are preparing to relaunch their offensive in northern Mali along the Algerian border for the first time since Tuareg militants defeated them in the area in July. Malian and Russian Ministry of Defense–linked Africa Corps troops received a significant number of new vehicles in Gao, a regional capital in northern Mali, between August 14 and 25.[50] Local sources estimated that between 600 and 800 Malian and Russian troops then deployed north from Gao in a 100-vehicle convoy on August 30 and are expected to arrive in the northernmost regional capital, Kidal, on September 15.[51] Malian forces and their Burkinabe allies have also conducted at least 10 drone strikes targeting the area near the border town Tinzaouten since July 27, presumably to degrade insurgent support zones in the area.[52]

Figure 5. Malian and Russian Forces Battle Tuareg Insurgents in Northern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

Malian and Russian forces are presumably aiming to capture the border town Tinzaouten, where Tuareg rebels repelled their previous offensive in a deadly ambush. Malian and Russian forces launched an offensive in late June to clear Tuareg insurgents from remote areas of northern Mali outside of the regional capital, Kidal city.[53] Tuareg militants ambushed a Malian-Russian convoy approaching Tinzaouten on July 25, leading to several days of fighting as the convoy was halted and eventually retreated.[54] The battle resulted in the deaths of up to 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers and significant materiel losses.[55] CTP previously assessed that a variety of current and historical factors indicated that the militants had links to the Tuareg separatist rebel coalition and al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM).[56] The Associated Press and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty also reported that both groups may have coordinated separate ambushes against their shared enemy.[57]

Malian and Russian forces face several capacity and capability challenges to clear and hold the Algerian border and other remote areas of northern Mali. Security forces have partially addressed the immediate capacity issues that led to their July defeat. The 100-vehicle convoy is at least four times as large in terms of personnel and nearly eight times as large in terms of vehicles as the forces sent to capture the town in July.[58] The July convoy initially consisted of only 12 vehicles that received no more than 70 additional soldiers as reinforcements.[59] This small contingent faced an overwhelming force of over 1,000 insurgents.[60]

However, security forces still likely lack the capacity to hold remote territory. Security forces were unable to hold positions along the border in July, so their convoys patrolled areas for a few hours before withdrawing to their bases farther south, allowing the militants to reenter the area.[61] Local Tuareg sources also claim that the new convoy is taking an alternate route to the border due to fears of improvised explosive devices on the main route, which is an area that Malian and Russian forces previously cleared in late June and early July but have evidently not held.[62] Malian and Russian forces previously took control of forward operating bases to help hold newly contested positions during their initial offensive into northern Mali to capture Kidal, in late 2023.[63]

Malian and Russian forces risk creating gaps for JNIM to exploit in other parts of the country by giving greater priority to northern Mali. Russian forces have been essential to the capture of other longtime rebel strongholds in northern Mali since late 2023.[64] However, CTP previously reported during the late 2023 offensive against Kidal that this focus decreased Malian-Russian operations in central Mali.[65] A similar pattern would risk JNIM making significant gains in more populated and politically important areas of central Mali, which plays into JNIM’s strategy given that the UN reported that JNIM has already prioritized central Mali over northern Mali in 2024.[66] However, CTP has not yet observed any notable change in operations outside of northern Mali during the current military buildup.[67]

Malian forces and their Russian partners will also likely remain reliant on Burkinabe and Malian air support. The Malian and Russian official accounts of the July attack separately attributed the defeat to a sandstorm that halted the convoy and prevented air support from intervening in the battle.[68] Drone support had previously driven the separatist rebels from the military base in Tinzaouten in December 2023 and contributed to the successful Malian-Russian offensive in northern Mali in late 2023.[69] Air support degrades insurgents’ ability to carry out effective ambushes by spotting and targeting massed insurgent forces. The continued drone strikes around Tinzaouten indicate that security forces are still counting on this air support, especially given that the insurgents maintain numerical superiority if they can gather up to 1,000 militants as they did in July.[70]

Security forces are unlikely to permanently degrade support zones along and across the Algerian border due to Mali’s strained ties with Algeria.[71] Algeria mediated and strongly supported the 2015 peace agreement between the Malian government and separatist Tuareg rebels and attempted to salvage the deal in December 2023 due to fears that renewed hostilities in Mali would mobilize the Tuareg population in Algeria and cause refugees to flee to Algeria.[72] Mali withdrew its ambassador from Algeria in retaliation for those efforts and accused Algeria of undermining its sovereignty as it formally withdrew from the peace agreement in January 2024.[73]

Algeria has repeatedly signaled strong opposition to Malian military activities along, and especially across, its border. Algeria conducted live ammunition military drills on its border with Mali in February 2024 to deter Malian overreach.[74] Algeria’s representative to the UN called for accountability for human rights abuses and an end to “mercenary activities” in Mali on August 27 in a statement following multiple drone strikes near Tinzaouten that killed civilians.[75]

Russian military commentators framing the Russian units participating in the offensive as part of the Russian MoD-linked Africa Corps may indicate that the MoD has consolidated greater control over the Russian presence in Mali. Prominent Russian military commentators said in the aftermath of the July attack that the Ministry of Defense (MoD) would use the incident to replace Wagner Group fighters with Africa Corps recruits.[76] The MoD created the Africa Corps to formally take over the Wagner Group’s operations in Mali in late 2023 as part of its efforts to subsume Wagner’s global portfolio following the death of Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, in August 2023.[77] Russian MoD personnel already heavily supported Wagner’s activity Mali before the creation of Africa Corps, and Wagner was left virtually untouched in Mali as long as fighters signed MoD contracts, meaning there was little tangible change for Russian forces in the country.[78]

The Russian characterization of the latest offensive as an Africa Corps operation would signal an inflection in the Kremlin’s efforts to brand its activity in Mali. Russia maintained Wagner Group imagery as part of its operations in Mali to keep a thin veneer of plausible deniability.[79] This move has given the Malian junta the confidence to keep lying about the presence of Russian forces in Mali.[80] This framing also enabled Russia to frame blunders like the July ambush as a Wagner defeat instead of a Russian defeat.[81]