Key Takeaways:

- Horn of Africa. Egypt is growing military cooperation with Somalia and deployed troops to Somalia, which is increasing tensions with Ethiopia and raising the risk of direct or proxy military clashes between Egypt and Somalia against Ethiopia. The Somali Federal Government is trying to pressure Ethiopia to withdraw its military forces from Somalia and annul its port agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Egypt wants to counter Ethiopia’s growing influence on the Nile and Red Sea, which are economically vital waterways for Egypt. Ethiopia has strongly warned that the growing Egyptian military presence on its border poses a national security threat. The African Union peacekeeping transition at the end of 2024 is a potential trigger that could transform the rising political tensions into an armed conflict between Egyptian and Somali forces against Ethiopian soldiers or pro-Ethiopian Somali forces. The growing tensions could derail Turkish-led peace talks scheduled for later in September.

- Niger. ISSP has cut off a district capital in western Niger, threatening to expand its control in the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger border area. Stronger Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) support in this area would enable the group to project greater pressure on roadways connecting Niger to Burkina Faso and Mali. The military setback in northwestern Niger is also undermining internal support for the Nigerien junta among the army.

- Burkina Faso. Burkina Faso is advancing its nuclear energy goals with Russian support. Russia is using nuclear energy diplomacy in Burkina Faso and across Africa to spread its influence and create economic opportunities for itself.

- Assessments:

Horn of Africa

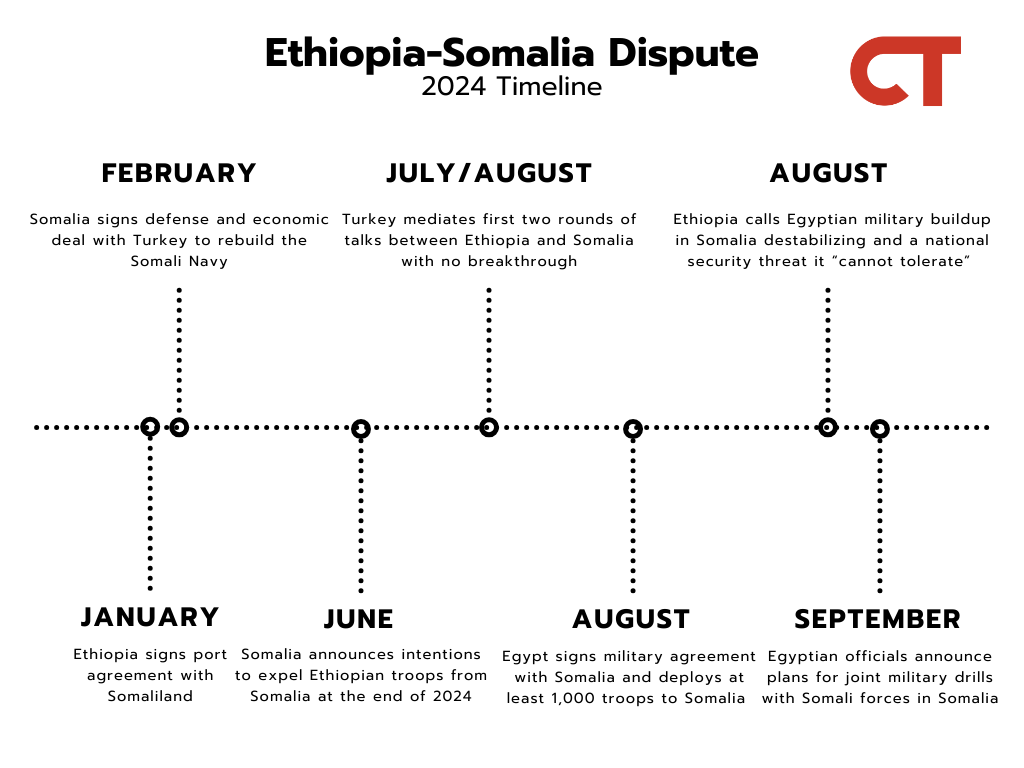

Egypt is growing military cooperation with Somalia and deployed troops to Somalia, which is increasing regional tensions between Egypt and Somalia against Ethiopia. Egypt and Somalia signed a bilateral defense cooperation agreement when Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud visited his Egyptian counterpart, Abdel Fattah el Sisi, in Cairo in August.[1] The African Union (AU) and Egypt also separately said in August that Egypt would contribute to the multilateral AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia that will begin in 2025 after the current mission wraps at the end of 2024.[2] International media reported that 5,000 Egyptian troops will deploy to Somalia around Mogadishu as part of the mission, while Egyptian media said the deployment could be as many as 10,000.[3]

Egypt then sent 1,000 soldiers and arms and ammunition to Mogadishu between August 27 and 29.[4] Egyptian officials said Egypt would ship armored vehicles, rocket launchers, artillery, anti-tank missiles, radars, and drones as part of the defense deal. Egypt and Somalia are also planning to hold joint military exercises in Somalia sometime in September.[5] Egyptian officials said the exercise will involve ground, air, and naval forces and “send a clear and loud message about our firm commitment to co-operate and protect Somalia.”[6]

The Somali Federal Government is trying to pressure Ethiopia to withdraw its military forces from Somalia and annul its port agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Relations between Ethiopia and Somalia have rapidly worsened since Ethiopia signed an agreement with Somaliland in January. The deal involved Ethiopia receiving land for a potential civilian- or military-use port on the Somaliland coast that would grant Ethiopia Red Sea access via the Bab al Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen in exchange for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[7] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has described Red Sea access as an existential issue and “natural right” that Ethiopia would fight for if it could not secure it through peaceful means.[8]

The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty and threatened to “retaliate” if Ethiopia followed through.[9] Relations between the two countries continued to deteriorate as Ethiopia has continued bypassing the SFG and building diplomatic ties with local officials in Somaliland and other parts of Somalia to pursue its goals while attempting to sideline the SFG.[10] Somali officials announced in June that the SFG plans to expel Ethiopian forces from Somalia after the conclusion of the current AU mission at the end of 2024 unless Ethiopia revokes its port deal with Somaliland.[11] Ethiopia has been a part of the AU peacekeeping forces in Somalia since 2014 and has more than 4,000 troops in Somalia as part of the current AU peacekeeping mission fighting the Somali-based al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab.[12] Ethiopia also has thousands of additional soldiers in the regions of central and southern Somalia that border Ethiopia through bilateral agreements with the SFG.[13]

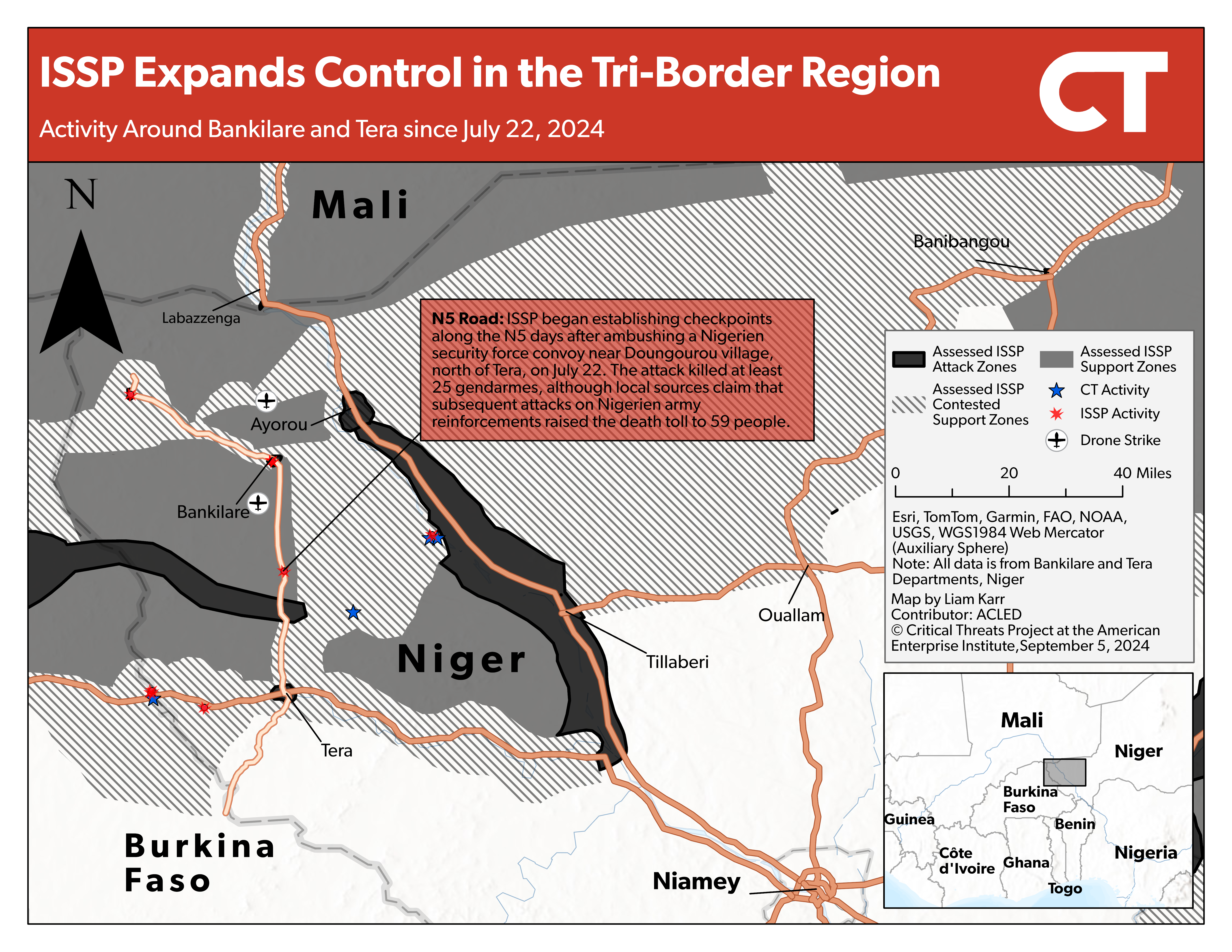

Figure 1. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

Egypt wants to counter Ethiopia’s growing influence on the Nile and Red Sea, which are economically vital waterways for Egypt. Egypt has sought to strengthen ties with Somalia since before 2024 to court Somali support for its position on Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).[14] The GERD has been a point of contention for Egypt since Ethiopia began its construction on the Nile River, in 2011.[15] Egypt has repeatedly labeled the GERD an existential threat that will degrade—or enable Ethiopia to control—its Nile water supply.[16] The Nile is vital for Egypt’s economy and general population given it gets 90 percent of all its water from the Nile, which it uses for electric production, agriculture, and drinking water.[17] Ethiopia has framed the project as key to its economic development, energy independence, and national unity.[18] Egypt has argued that Ethiopia should not fill the GERD without a legally binding agreement that resolves concerns about the dam’s downstream effects.[19]

Somalia has become Egypt’s best potential partner to counter Ethiopia since the outbreak of the Sudanese civil war, which degraded Egypt’s influence in Sudan. The ruling Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) had backed Egypt’s stance on the GERD as Sudan is another downstream Nile country. The two partners conducted military drills and had stationed Egyptian fighter jets in Sudan since 2020 to pressure Ethiopia towards an agreement.[20] The Sudanese civil war has preoccupied the SAF and nullified Egypt’s military capacity in Sudan. Rival Sudanese forces destroyed some of the fighter jets Egypt had stationed in Sudan and captured Egyptian pilots in the early days of the war, which led Egypt to withdraw its remaining assets and personnel.[21]

Egypt also likely wants to deny Ethiopia Red Sea naval access, which would create opportunities for Ethiopia to threaten Egypt’s Red Sea rents in the far future. Egypt received roughly $9 billion annually from Suez Canal receipts before the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, which began in October, and the subsequent Yemeni-based Houthi campaign in the Red Sea.[22] The Houthi attacks have more than halved this figure in 2024.[23] Ethiopia signed defense accords with France to reestablish its defunct navy in 2019 but has not made notable progress since.[24]

Ethiopia has strongly warned that the growing Egyptian military presence on its border poses a national security threat. The Ethiopian foreign affairs ministry released a statement on August 28 implicitly warning Egypt and the international community against Egyptian military involvement in the new AU mission and Somalia more broadly.[25] The statement repeatedly accused external actors—presumably Egypt—of destabilizing the region and said that it “must shoulder the grave ramifications” of doing so. Ethiopia framed these concerns as potential threats to its national security and actions that it “cannot tolerate.” Multiple local reporters have reported that Ethiopia began building up its military forces in the Ogaden region, which borders Somalia, in August.[26]

The AU peacekeeping transition at the end of 2024 is a potential trigger that could transform the rising political tensions into an armed conflict between Egyptian and Somali forces against Ethiopian soldiers. Ethiopian officials have implied that Ethiopian troops will stay in Somalia past 2024 if Ethiopia has international and local support regardless of the SFG’s actions.[27] Local leaders and politicians in parts of southwestern Somalia have spoken out against the SFG’s plans to expel Ethiopian soldiers.[28] Ethiopia’s position is consistent with CTP’s previous assessment that Ethiopian forces will almost certainly try to remain in Somalia to maintain a buffer zone against al Shabaab and prevent an al Shabaab offensive into Ethiopia, as the group launched in 2022.[29] Ethiopia’s stated national security concerns about the Egyptian military buildup in Somalia further incentivize it to maintain this buffer zone.

Ethiopian forces remaining in Somalia without SFG approval would provide a clear pretext for Somalia, with Egyptian support, to attack Ethiopian soldiers on Somali soil or along the border. The SFG has repeatedly condemned Ethiopia for violating its sovereignty throughout 2024 and threatened to retaliate.[30] Sisi has warned that Egypt would protect Somalia from any threats to its sovereignty on multiple occasions and explicitly threatened Ethiopia to “not try Egypt, or try to threaten its brothers especially if they ask it to intervene” after meeting with the Somali president in January.[31] Egypt’s GERD concerns also give it internal reasons to support military intervention against Ethiopia. Egypt wrote to the UN Security Council on September 1 that Ethiopia’s unilateral policy on the GERD “threatens the stability of the region” and that Egypt is “prepared to take all measures and steps guaranteed under the UN Charter” to defend itself after Ethiopia began the fifth stage of filling the GERD.[32]

The timing and nature of Egypt and Somalia’s recent military cooperation also signal both countries’ intent to threaten Ethiopia and indicate that their military buildup is not tied purely to the AU peacekeeping mission. Egyptian troops have arrived months before the planned AU transition at the end of 2024. Furthermore, the AU and UN will not finalize the new mission’s funding, concept of operations, and other troop-contributing countries until October.[33] This timing discrepancy indicates that the soldiers are not primarily there as part of the planned peacekeeping mission. The anti-tank missiles Egypt plans to send are also more geared for a conventional conflict, as al Shabaab does not use sophisticated enough vehicles to require anti-tank weapons.

The upcoming Egypt-Somalia military exercise will likely underscore the cooperation’s anti-Ethiopian intentions. Egyptian officials announced their plans for the military exercise one day after their September 1 warning about Ethiopia’s GERD activity.[34] Egypt previously used military exercises with Sudan to pressure Ethiopia on GERD negotiations.[35] Egyptian officials also said the exercise aims to “send a clear and loud message about our firm commitment to co-operate and protect Somalia.”[36] This framing is consistent with Egypt’s previous promises to protect Somali sovereignty from Ethiopia throughout 2024, indicating that the exercises are a message to Ethiopia and not counterinsurgency operations.[37] Military exercise in regions of Somalia bordering Ethiopia would further indicate the anti-Ethiopian nature of the exercises by putting Egyptian forces within range of Ethiopian soldiers and outside of their reported AU peacekeeping area of responsibility around Mogadishu.

Ethiopia’s strong ties to various local actors in Somalia also increase the risk of an armed proxy conflict in Somalia between the SFG and pro-Ethiopian regional Somali administrations, even if Ethiopian forces withdraw. Multiple leaders and politicians in Somalia’s Jubbaland and South West states have spoken out against the SFG’s plans to expel Ethiopian troops.[38] Many of the Somali forces that operate in these states alongside Ethiopian soldiers respond to their clan and regional leaders, not federal entities like the Somali National Army or the SFG.[39] Disagreements between the federal government and these local factions have historically led to clashes between local and national forces, often the local factions receiving external backing from Ethiopia or Kenya.[40]

The SFG has already begun retaliating against local politicians speaking out in favor of Ethiopia, marginalizing these communities and increasing the risk of an internal conflict. President Mohamud fired his special envoy for health and nutrition on September 1 after the envoy voiced support for Ethiopian troops remaining in Somalia and warned against bringing the Nile conflict (i.e., the GERD dispute) to Somalia.[41] The Somali parliament is attempting to pass a law to strip immunity from 25 members of parliament from South West state that have voiced support for a continued Ethiopian military presence in Somalia.[42]

The growing tensions could undermine upcoming Turkish-led peace talks between Ethiopia and Somalia. Turkey mediated talks between Ethiopia and Somalia in Ankara in July and August and will host a third round of discussions on September 17.[43] The effort has failed to yield a breakthrough, and both sides have accused each other of wanting to destabilize the other.[44] The Somali minister of foreign affairs left the August meeting blaming Ethiopia for the talks’ collapsing.[45] Ethiopia also blamed Somalia for “colluding with external actors aiming to destabilize the region” instead of pursuing the peace talks.[46]

Turkey’s recent rapprochement with Egypt will also impact its mediator role. Sisi met with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on September 5 for the first time since Sisi took power in 2013, which led Turkey to cut ties with Egypt and shelter the Muslim Brotherhood leaders that Sisi overthrew.[47] Turkey had also been a steadfast supporter of Ethiopia on the GERD issue in recent years.[48] Egypt and Turkey signed 17 bilateral agreements during Sisi’s visit and discussed the need to “preserve the unity and territorial integrity” of Somalia among other issues.[49] Turkey’s rapprochement with Egypt better positions it as a negotiator with strong ties to Egypt, Ethiopia, and Somalia. However, Turkey also risks alienating Ethiopia and diminishing its status as an impartial mediator given that Ethiopia will presumably view Turkey’s growing ties to Egypt and Somalia as a threat.

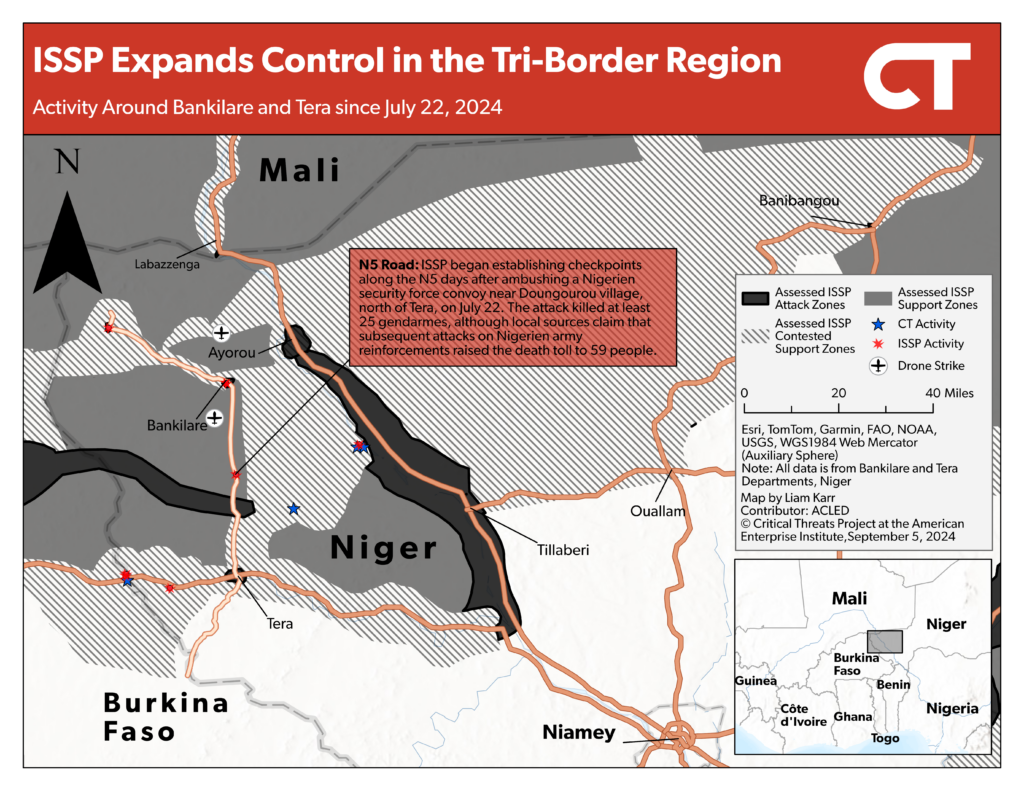

Niger

ISSP has cut off a district capital in western Niger, threatening to expand its control in the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger border area. The Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) carried out another large ambush targeting a Nigerien security force convoy traveling on the N5 road between the district capitals Bankilare and Tera on July 22.[50] IS and local sources claimed that the attack killed around 25 gendarmes, although some local sources said attacks on Nigerien army reinforcements raised the death toll to 59.[51]

Figure 2. ISSP Expands Control in the Tri-Border Region

Note: All data are from Bankilare and Tera Departments, Niger.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

Locals reported that ISSP has now taken control of the N5 between Bankilare and Tera. ISSP militants have established checkpoints along the route and denied security forces access to the road.[52] The group has encircled the army base in Bankilare, which is just under 50 miles north of Tera, and prevented reinforcements and supplies from reaching the base.[53] ISSP ambushed a Nigerien convoy trying to aid the base on September 1, killing another 20 soldiers.[54]

ISSP’s recent gains are a significant setback given that security forces had strongly contested the group in this area over the previous year to prevent the group from establishing strong support zones but are now unable to exert the same level of counterinsurgency pressure. The junta gave greater priority to contesting ISSP in the Tera department over other parts of the country in the first year of its rule between August 2023 and July 2024.[55] Nearly one-quarter of all ground operations in this period occurred in Tera.[56] Government activity in the area also included an uptick in activity shortly before the ambush in July 2024. Nigerien forces conducted nine operations against ISSP in Bankilare and Tera departments, in July compared with eight in the entire first half of 2024.[57] CTP assessed in July that these efforts and communal mobilization had possibly contributed to ISSP’s failure to establish strong support zones in most of this area.[58] Taxation and movement reports have decreased in the post-coup period.[59]

The attack and subsequent isolation of Nigerien forces has led to a significant reduction in counterinsurgency pressure. The attack has shattered morale, leading anonymous soldiers to report that at least one lieutenant and several soldiers deserted.[60] The poor morale and lack of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support have led the soldiers to significantly decrease offensive operations. The Nigerien authorities attempted to establish a truce with the ISSP, but the group executed the government emissaries.[61]

Stronger ISSP support in this area would enable the group to project greater pressure on roadways connecting Niger to Burkina Faso and Mali. The N5 connects to the N23 highway that links northwestern Niger and Burkina Faso, and Bankilare is less than 20 miles from the N1 road that connects western Niger to Mali. ISSP already regularly attacks civilians and security forces traveling on the N1 and N23 roads but has not established uncontested control over either road to the extent it now controls the N5.

ISSP further degrading civilian or military freedom of movement on these roads would hinder the Sahelian states’ ability to conduct joint operations targeting insurgent havens along the border. Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger agreed in March to increase joint counterinsurgency operations along their borders.[62] Nigerien forces participated in some patrols along roads that extend into Burkina Faso in June.[63] ISSP degrading the ability of Nigerien forces to use these roads would challenge their ability to continue conducting such operations and strengthen ISSP’s border support zones.

Greater ISSP control of the roads would also harm local economies and create opportunities for greater ISSP taxation. The N1 road links northern Mali to the ports in Benin and Togo via Burkina Faso and Niger and is a part of two key trade corridors that the West African monetary union designated in 2009.[64] The N26 road is important for local cross-border communities and economies on both sides of the Burkina Faso and Niger border.[65] The N5 is also itself a crucial artery of a network of smaller roads that connect villages in the northwestern corner of Niger and run into Burkina Faso.

The military setback in northwestern Niger is also undermining internal support for the Nigerien junta among the army. Nigerien soldiers criticized the regional commander’s decision to not send air support or reinforcements during the July ambush and are reportedly angry with the junta hierarchy for not sending additional support to improve the situation.[66] The low morale and self-isolation in Bankilare is also present in other parts of northwestern Niger. Soldiers operating near the Tillaberi and Tahoua regional border refused to conduct patrols without air support or deserted their positions following a massive ISSP ambush that annihilated a convoy in July.[67] The attacks undermine the junta’s legitimacy among the military rank-and-file because the bulk of Nigerien forces acquiesced to the coup because they supported coup leaders’ messaging about correcting the democratic government’s counterinsurgency strategy.[68]

Degraded control of the key road arteries in western Niger would compound the junta’s preexisting economic woes, which also threaten its popular support. The junta is still experiencing significant economic shortfalls after regional and international sanctions and donor cuts contributed to the junta slashing its 2023 budget by 40 percent and defaulting on four debt payments totaling $519 million since taking power.[69] The World Bank projected Niger’s economic growth in 2024 to be 45 percent less than pre-coup estimates.[70] These issues have inflated food prices and contributed to at least 1.1 million Nigeriens falling below the extreme poverty threshold since the coup, bringing the total number to 14.1 million people—roughly 54 percent of the population.[71]

Burkina Faso

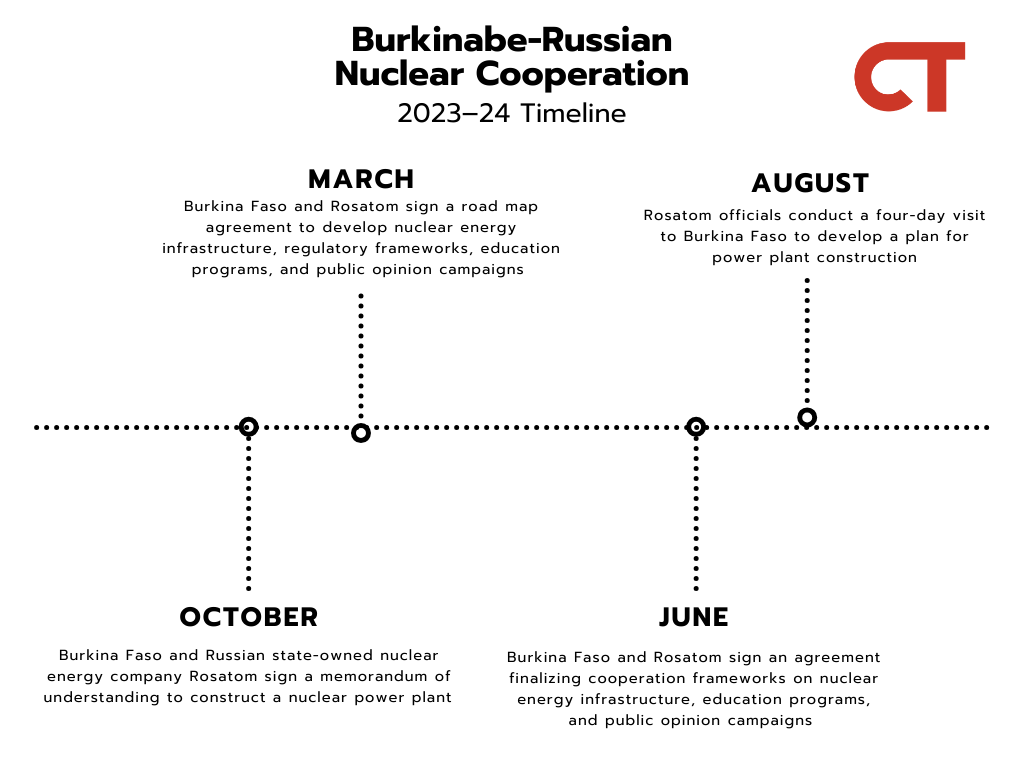

Burkina Faso is advancing its nuclear energy goals with Russian support. Officials from the Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom conducted a four-day visit to Ouagadougou in August 2024 to create a preconstruction checklist of prerequisites for Burkina Faso’s planned nuclear power plant.[72] The Burkinabe government also established an atomic energy agency, the Burkina Atomic Energy Agency (BAAE), on August 21.[73] The BAAE aims to ensure Burkina Faso’s energy independence and industrialization and facilitate access to electricity.[74]

Figure 3. Burkinabe-Russian Nuclear Cooperation: 2023–24 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

The Rosatom visit and creation of the BAAE is the latest step in growing Burkinabe and Russian cooperation on nuclear energy since October 2023. Burkina Faso signed a memorandum of understanding with Rosatom in October 2023 to construct a nuclear power plant and enhance nuclear energy cooperation.[75] Burkina Faso and Rosatom signed follow-up road map agreements in March, April, and June 2024 focusing on education and training, infrastructure, public education, and regulatory frameworks.[76] The Burkinabe government also passed a bill in July 2024 giving privileges and immunities to experts and International Atomic Energy Agency officials who will support the construction of its first nuclear power plant.[77]

Burkina Faso has lacked the domestic capacity to meet its electricity demands and sought to establish nuclear energy capabilities to address its shortfalls since 2021.[78] Burkina Faso produces roughly 782 million kilowatts of electricity a year, which is less than half its electricity consumption, roughly 2.1 billion kilowatts a year.[79] This gap has made Burkina Faso reliant on importing electricity largely from Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Togo.[80] The junta’s relationship with all three countries has deteriorated since it took power due to the regional West African economic and political bloc—the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)—levying sanctions that contributed to Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger leaving ECOWAS.[81] The junta has an especially contentious relationship with Côte d’Ivoire.[82] These political dynamics have likely created increased urgency for Burkina Faso to achieve energy independence. Burkina Faso has also lacked the electricity transmission infrastructure and regulatory framework required for a power plant, which Rosatom is helping address.[83]

Russia is using nuclear energy diplomacy in Burkina Faso and across Africa to spread its influence and create economic opportunities for itself. Russia has positioned itself as a global leader in the nuclear energy market, including in Africa.[84] This has led to numerous deals on peaceful nuclear technological cooperation and nuclear power plant construction.[85] These deals create multiple revenue and export market opportunities via Russia exporting nuclear energy technology, constructing power plants, and Russia’s large stake in the uranium market that power plants need to operate.[86] These opportunities make the Russian economy more resilient in the face of Western economic retaliation for its invasion of Ukraine.

Russia also uses these projects to expand its influence by making countries reliant on Russian financing and tech. [87] Russia finances a significant portion of these projects to ensure that it can engage with all potential partners.[88] The expertise and time required to build a nuclear power plant also makes countries dependent upon Russia for the project and solidifies long-term Russian engagement.[89]