The Guinean junta’s growing repression and intolerance for dissent risk derailing the promised transition back to civilian government while deepening the country’s humanitarian crisis.

Three members of the Guinean opposition—Oumar Sylla (also known as Foniké Menguè), Mamadou Billo Bah, and Mohammed Cissé—were arrested at Menguè’s home in Conakry on July 9, 2024 and taken to a detention facility on Kissa, an island off Conakry, where they were allegedly tortured. While Cissé was eventually released, Menguè and Bah remain unaccounted for. Their wives have filed a lawsuit against Guinea’s junta leader, Mamady Doumbouya, claiming he ordered their forced disappearance. These abductions represent a pattern of escalating harassment, jailings, and trials against critics of the junta, including popular rapper, Djanii Alfa.

The head of a Special Forces unit, Colonel Doumbouya seized power in a military coup on September 5, 2021. Under an agreement negotiated with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Doumbouya promised a transition back to civilian rule and democratic elections by the end of 2024.

Yet, the junta has not taken concrete steps to uphold this commitment and its members now refer to Doumbouya as President of the Republic, rather than president of the transition as they had previously.

Djanii Alfa

Rapper Djanii Alfa being detained by the military junta. (Screenshot: Lamarana Djebou Sow /AFP TV)

The military regime is increasingly resorting to repression to hold onto power. The junta has banned public protests—yet when Guinean citizens and civil society groups protest anyway, they are violently suppressed. Amnesty International estimates that at least 47 people have been killed by security forces during protests against the junta between June 2022 and March 2024.

Members of the bar have been on strike for weeks to protest the arbitrary arrests and unlawful detentions of Guinean citizens.

Media outlets that report on the protests or criticize the junta face closure. Journalists and media regulators who implicate the Doumbouya regime with corruption have been imprisoned for “defaming the head of state.”

Under the junta, the country is suffering from growing economic strains. Acute food insecurity has skyrocketed to an estimated 11 percent of Guinea’s 14 million people (from 2.6 percent in 2020). Over a million Guineans are now facing food crisis.

The junta’s intransigence in upholding the transition is reversing hard-won reforms to create a multiparty democracy in Guinea and risks reverting to the long, dark years of military rule and hardship that have defined the country’s post-independence trajectory.

Junta Violating its Own Benchmarks for Transition

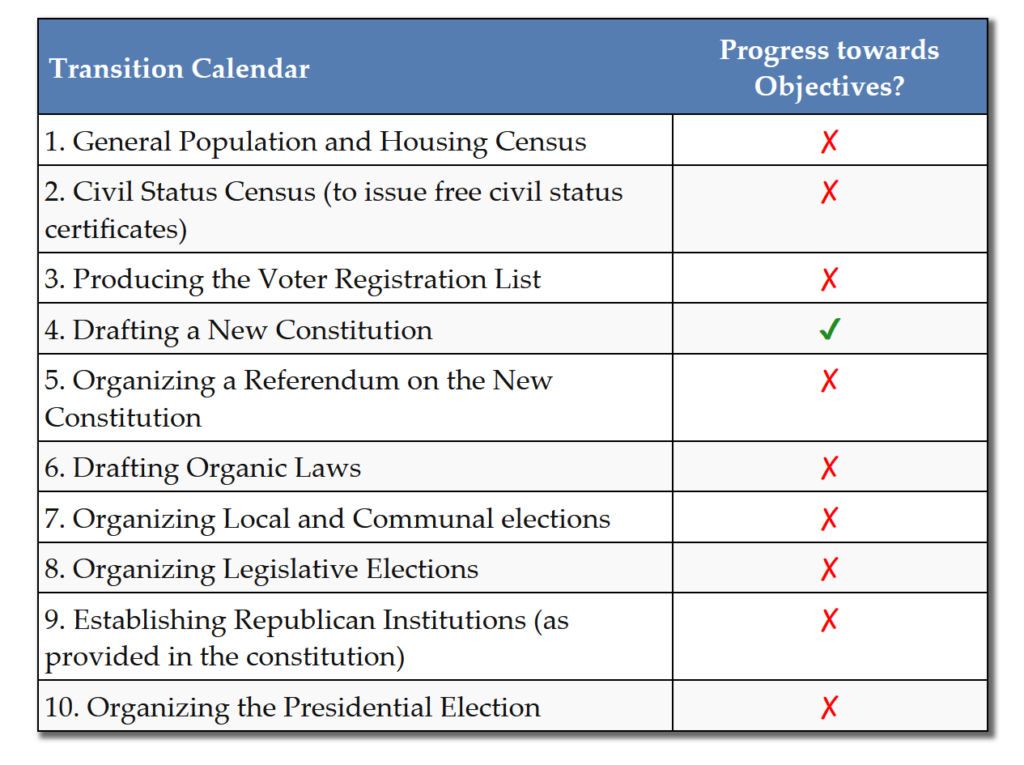

In an agreement with ECOWAS after the September 2021 coup, the Doumbouya junta promised to abide by a 10-point roadmap and presidential elections by December 2024. But the military government has failed to take concrete steps towards a transition. ECOWAS has condemned this lack of progress, but the junta insists that the transition plan must be completed in order, starting with a population census. The National Institute for Statistics, which is responsible for this initial step, has said that the census will not be completed until August 2025. Moving at the junta’s pace, the rest of the transition could be put off for years.

The proposed constitution appears to grant the junta and transitional council immunity for their actions in office.On July 31, 2024, the Doumbouya regime made public its proposed new constitution. The transitional council, which had been tasked with drafting the document, emphasized this was a working draft. This ambiguity further clouds the transition timetable. Substantively, the proposed constitution appears to grant the junta and transitional council immunity for their actions in office, further casting doubt on the legitimacy of the junta’s actions.

Opposition leaders are insisting that the elections be held as planned by December 2024. They have called for independent bodies to manage both the voter registration and election administration. The opposition also disputes that a new constitution is needed and argue that any constitutional reforms should wait until there is a legitimate, democratically elected government in place.

Further signaling the Doumbouya regime’s lack of commitment to a transition, junta spokesman Ousmane Gaoual Diallo said in a July 2024 interview that “a return to constitutional order doesn’t mean the end of the transition. These are two completely different themes. Everyone must understand that soldiers didn’t come to power to say, ‘we organize the election and then we move over so someone else takes over.’” He called the transition a medium-term program that could take up to another four years to “properly” implement.

Questioning of the Junta Is Not Tolerated

Building on its decades-long efforts to establish democracy despite entrenched military government, Guinea’s civil society has actively opposed the Doumbouya junta.

The Front National pour la Défense de la Constitution (the National Front for the Defense of the Constitution or FNDC), the main opposition coalition that had battled President Alpha Condé’s evasion of term limits, began calling for the junta to step down shortly after the coup in September 2021. The junta dissolved the FNDC in August 2022 and jailed at least three of its leaders, prompting the longtime opposition leader and democracy proponent, Cellou Dalein Diallo, and others to go into exile. Upon the jailed leaders’ release in May 2023, a broad alliance of opposition groups, including the FNDC and former pro-Condé parties, formed a new “Forces Vives de la Guinée” to denounce the shrinking democratic space.

In December 2021, the junta also established a new court, the Cour de répression des crimes économiques (the Court to Stop Economic Crimes or CRIEF), ostensibly to prosecute economic crimes. In practice, the court has only investigated, tried, and convicted former members of government and members of the opposition, leading the FNDC to call the CRIEF a tool of political repression.

Intolerance of dissent is not limited to political opponents. Following the December 2023 fuel depot explosion in Conakry that killed 24 people and destroyed 800 buildings, a communal advocacy council was formed to raise awareness of the victims’ plight and petition the government to rebuild the houses lost. Instead, the junta sent security forces to the high school where the communal council’s leader worked, used tear gas to disperse students, and arrested him. He was tried and convicted for criticizing the authorities and inciting unrest.

General Sadiba Koulibaly

General Sadiba Koulibaly who died in prison under mysterious circumstances in June 2024. (Photo: lelynx)

Dissent is not tolerated even, or perhaps especially, among the junta’s core members. General Sadiba Koulibaly, the former number two of the junta, had served as Chief of the Armed Forces between the coup and March 2023, when he was named Ambassador to Cuba. When he subsequently traveled to Conakry, reportedly to request that Embassy personnel in Havana be paid their salary arrears, he was instead arrested on June 4, 2024. His lightning trial saw him convicted for desertion abroad, rebellion, attempted murder, and illegal weapons possession. On June 14 he was sentenced to five years in prison. General Koulibaly died in prison under mysterious circumstances on June 22.

Media space is also shrinking, limiting information into and out of Guinea. The junta has restricted internet access, stopped TV and radio channels from broadcasting, and pursued a crackdown on independent private media. Sékou Jamal Pendessa, the Secretary General of Guinea’s Union of Professional Journalists, was sentenced in February 2024 to six months in jail for organizing a protest, threatening public order and the dignity of people through information technology. In July, two media regulators, Djene Diaby and Tawel Camara, from the 13-member High Authority for Communication, were convicted of defaming the head of state after they claimed that the junta had bribed the executives of two (since banned) popular media outlets in exchange for positive coverage.

A Long History of Disastrous Military Rule

Since its independence in 1958, Guinea has suffered under more than 50 years of dictatorial rule, of which the military has directly or indirectly played a central part. This includes the oppressive 25-year regime of Sekou Touré (1958–1984) in which 50,000 people are estimated to have been killed by the government, the 24-year military regime (1984–2008) of General Lansana Conté, and the military junta of Dadis Camara (2008-2010) under which an estimated 150 people were killed by the military and hundreds of women raped in the infamous stadium massacre.

The military’s decades-long stranglehold on Guinean society has left the country one of the poorest in Africa, despite being endowed with a quarter of the world’s bauxite reserves. Under Conté, the economy largely contracted, and an estimated 1.5 million Guineans fled the country. Between 1985 and 2010, median annual per capita economic growth was stagnant at 1.1 percent. By comparison, in the decade after Guinea’s democratic opening in 2010, the country realized median annual economic growth of 3 percent.

By seizing power, the Doumbouya (who promoted himself to General in 2024) junta is seemingly aiming to assert the Guinean military’s perceived entitlement to rule. In the process, it risks extending the military’s ignominious legacy.

The military’s decades-long stranglehold on Guinean society has left the country one of the poorest in Africa.Under the Doumbouya junta, life for ordinary Guineans has grown more difficult. Just in 2024, the price of a 50 kg bag of rice has increased from $35 to $39 and the cost of a 20 liter can of cooking oil has risen from $30 to nearly $34. The percentage of the Guinean population living in acute food insecurity rose from 2.6 percent in 2020 to 10.7 percent in 2022. In December 2021, 564,458 Guineans were considered to be facing a food crisis and in need of assistance. By June 2024, this figure had climbed to an estimated 1,025,035.

The deteriorating food situation is remarkable in that acute food insecurity in Africa is typically associated with conflict, something Guinea has thus far been able to avoid.

A 2023 Afrobarometer survey found that 55 percent of Guineans felt economic conditions were deteriorating compared to a year earlier. Indicative of the worsening economic conditions and growing repression, 21,693 Guineans arrived in Europe in 2023, compared to 3,034 in 2021.

Security Risks Increasing in Guinea

Unlike the military juntas in Mali and Burkina Faso who justified taking power on the security threat from violent extremists, Guinea has not, to date, been subject to such attacks.

Guinea detail of Militant Islamist-Linked Violent Events bordering Coastal West Africa

Militant Islamist-linked violent events bordering Guinea. (See: Recalibrating Coastal West Africa’s Response to Violent Extremism)

Nonetheless, violent extremist events in regions of Mali along the Guinean border have increased from one in 2023 to a projected 19 in 2024—posing a serious threat of spilling into Guinea. The slowness of West African governments to support development and establish cooperative relationships with border communities has been a key vulnerability to the encroachment and spread of these extremist groups. Under the Guinean junta’s rule, there has been little prioritization or expertise dedicated to such stabilizing development and governance initiatives.

Reflective of the growing repression and external threats, Guinea’s Global Peace Index ranking dropped from 96th (out of 163 countries) in 2018 (medium) to 124th in 2024 (low). In 2022, Guinea had the largest deterioration in peacefulness in Africa—ahead of Burkina Faso (and second only to Ukraine on a global level).

Decreasing Transparency in Management of Government Resources

While the junta has pledged transparency and accountability in the mining sector, this has not materialized. In a report on corruption in Guinea’s mining sector, researchers with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) noted that accountants of a private mining firm refused to share requested information with a tax inspector because the company only provides that information directly to the office of the presidency.

This is significant as the junta has renegotiated contracts to develop the world’s largest unexploited bauxite mine (Simandou), which are proceeding with little accountability for local communities’ interests. When fully operational, the mine is expected to generate $1 billion in revenues annually. Currently, total government revenues are less than $4 billion. Meanwhile, several independent institutions dedicated to fighting corruption and providing oversight have been moved to the office of the presidency, preventing effective oversight.

Institutions dedicated to fighting corruption and providing oversight have been moved to the office of the presidency.As part of the investigation into the December 2023 fuel depot explosion in Conakry, a leaked audit report of the Société nationale des pétroles (the National Petroleum Company or SONAP) by the Minister of the Economy and the Inspector General of Finances alleged fraud at SONAP. SONAP is headed by a close confidant of Doumbouya, Amadou Doumbouya (no relation to the junta leader). The audit found that under an oil imports contract signed between SONAP and the Nigerian trader Sahara Energy Resource Limited in March 2022, the trading fee Guinea was paying had increased from $53 dollars a ton to $115 a ton, citing the war in Ukraine. Yet, this fee has not been reduced since, despite the decline in the price of a barrel of oil from around $105 to $78. SONAP has also instituted a five-fold increase in the fee paid by customers (from 35 to 150 francs per liter) compared to the rate under Alpha Condé.

Guinean journalists, meanwhile, have reported that Amadou Doumbouya allegedly purchased a $1 million dollar house in Texas in 2022. In January 2024, French journalist Thomas Dietrich, who had been investigating corruption at SONAP, was expelled from Guinea.

The Guinean government has also become more militarized under the junta. In 2022, Doumbouya replaced the country’s 34 civilian prefects with military officers. In March 2024, Doumbouya dissolved the country’s 342 elected municipal councils, again directly appointing their 3,000 replacements. Without irony, Doumbouya cited the fact that their elected mandate had expired, making them “illegitimate.” The opposition has claimed these nominations are a means of extending the junta’s control of government. Among other responsibilities affecting the day-to-day lives of citizens, municipal councils are typically charged with organizing elections.

Flying under the Radar

While not attracting the level of international attention as the Sahelian juntas, Guinea’s military government has taken clear steps to consolidate its hold on power over the past year. This has been accompanied by slow rolling the transitional calendar while crushing dissent. As the transition is delayed, the junta extends its hold over society by placing loyalists at all levels of national and local government. Despite releasing a draft constitution, the junta is now openly admitting that it has no plans to leave power, even when the transition benchmarks are met. In effect, the military is reasserting its long-held role as the sole source of power in Guinea.

Besides undermining Guineans’ hard-fought efforts to establish a functional and peaceful democracy, the junta’s intent to hold power indefinitely appears set to amplify food, migration, and security threats that will have implications across the region.