The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

- Somalia. The African Union (AU) and UN are advancing plans for an AU-led peacekeeping mission in Somalia after the current AU mission expires, at the end of 2024. The new mission will prioritize ongoing peace-building measures and defer state-building efforts to international partners and the Somali Federal Government (SFG). Egypt plans to contribute to the AU mission for the first time, while four of the five current troop-contributing countries—including Ethiopia—have not confirmed their participation.

- Burkina Faso. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate JNIM carried out its deadliest attack ever against Burkinabe forces in early August, which adds to growing internal pressure to overthrow Burkinabe junta leader Ibrahim Traore. The Burkinabe junta’s focus on regime stability over counterinsurgency operations will reduce pressure on insurgent support zones, enabling the militants to continue carrying out destabilizing large-scale attacks.

- Assessments:

Somalia

The AU and UN are advancing plans for an AU-led peacekeeping mission in Somalia after the current AU mission expires at the end of 2024. The African Union (AU) endorsed plans for a successor mission in June 2024, adopted a strategic concept of operations (CONOPs) in early August, and forwarded the CONOPs for the new AU Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) to the UN Security Council for approval in mid-August.[1] Ethiopian Foreign Affairs Spokesperson Nebiyu Tedla said that the AU and UN want to finalize the political, financial, and logistical arrangements sometime between October and December.[2]

The new mission will prioritize ongoing peace-building measures—such as providing security to Somali citizens and degrading al Shabaab—while leaving international partners and the Somali Federal Government to work on state-building. The new mission’s security goals carry over directly from the African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) mandate and will have a similar force size to the current ATMIS mission.[3] ATMIS began in 2022 with over 20,000 troops but has implemented a staged drawdown since 2023 to 12,626 uniformed personnel who will stay in the country through the mission’s completion, at the end of 2024.[4] The AUSSOM CONOPs says the mission will have 11,911 personnel.[5] The AUSSOM CONOPs also says the mission will have four sectors, which will require AU forces to combine areas or transition them to Somali control across the six ATMIS sectors.

The AU has called on other partners to take the lead on state-building tasks and framed the new mission as an enabler for such efforts. International organizations define peace-building as “strengthening national capacities . . . for conflict management” to reduce the risk of conflict, whereas state-building is “an endogenous process to enhance capacity, institutions, and legitimacy of the state driven by state-society relations.”[6] There is significant overlap between the new mission’s peace-building objectives and some aspects of state-building, such as improving the capacity of Somali forces, helping with reconstruction and development, and fostering good practices that encourage strong civil-military relations. However, the AU has emphasized that the new mission’s peace-building and post-conflict development goals are a way to “enable” broader state-building goals in coordination with the SFG and other partners and specifically called for “scaling up” assistance to the SFG to mobilize resources for those efforts.[7] This language differs from the ATMIS and AU Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) frameworks, which directly mandated the mission itself to “coordinate” state-building activities and help the SFG “carry out their functions of government.” [8]

Egypt plans to contribute to the AU mission for the first time, while four of the five current troop-contributing countries—including Ethiopia—have not confirmed their continued participation. The AU said that it accepted Egypt’s offer in its August 1 letter, and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi confirmed that Egypt will contribute troops when Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud visited Cairo on August 14.[9]

Egypt’s involvement in the AU mission reflects growing ties between Egypt and Somalia since the current SFG administration took office in 2022 and likely aims to strengthen Egypt’s position vis-à-vis Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa.[10] Egypt aims to court Somali support for Egypt’s position in contentious issues with Ethiopia, such as Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project. The GERD has been a major point of contention with Egypt since Ethiopia began its construction on the Nile River in 2011.[11] Egypt also opened a new embassy in Mogadishu and signed a defense pact with Somalia in August 2024.[12]

Ethiopia has not been confirmed as a troop contributor even though it contributes at least 3,000 troops to ATMIS and has thousands of additional troops stationed in Somalia as part of bilateral agreements with the SFG.[13] Somali National Security Advisor Hussein Sheikh Ali said in June that the SFG would expel Ethiopian forces after ATMIS expires unless Ethiopia repeals the controversial port deal it signed with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region.[14] CTP previously assessed that Ethiopia will almost certainly maintain its presence in Somalia because its forces create a buffer zone against al Shabaab that Ethiopia views as essential to its national security. Furthermore, the local Somali forces and leaders in the areas where Ethiopian forces are stationed have voiced support for retaining Ethiopian troops in the country, further undermining the SFG’s ability to pressure Ethiopia to leave.[15]

Djibouti is the only confirmed returning troop contributor. Djibouti was the smallest ATMIS troops contributor based on all five countries’ prior contributions to the AU mission that preceded ATMIS. Djibouti contributed 960 troops, compared with at least 3,600 from each of the other four countries.[16] Burundi, Kenya, and Uganda have not confirmed that they will participate in the new AU mission.

The AU plans to fund the mission through UN-assessed contributions instead of relying on specific donors. UN-assessed contributions are pools of money shared among the member states based on their gross domestic product that the UN General Assembly determines is needed to finance an approved expense.[17] Western partners aired concerns about continuing to fund a new mission due to worries about long-term financing and sustainability, leading the AU and EU to push for member-contribution funding.[18] This will be the first use of a new UN resolution from December 2023 that enables assessed contributions to be used towards AU-led peace and security operations.[19]

The AU repeated its warning that the ongoing ATMIS drawdown and eventual AUSSOM transition is creating gaps for al Shabaab to attack or take over areas that ATMIS transitions to unprepared or overstretched Somali forces. The AU and SFG already released a joint assessment in March that the “hasty drawdown” of ATMIS personnel would contribute to capacity gaps and a resulting security vacuum, prompting an adjusted withdrawal schedule and discussions for a continued mission.[20] The August 1 AU statement explicitly called for an internal assessment on the impact and implications of the ongoing ATMIS drawdown by September to avoid any security vacuum.[21]

Al Shabaab is waging a campaign targeting bases that AU forces are transitioning to Somali control. The group conducted a suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device attack targeting a base in a regional capital in central Somalia on June 30 the day Djiboutian forces handed the base to the Somali National Army (SNA).[22] Al Shabaab also briefly overran a military base in central Somalia on August 13 that ATMIS forces had recently transitioned to the SNA.[23]

Burkina Faso

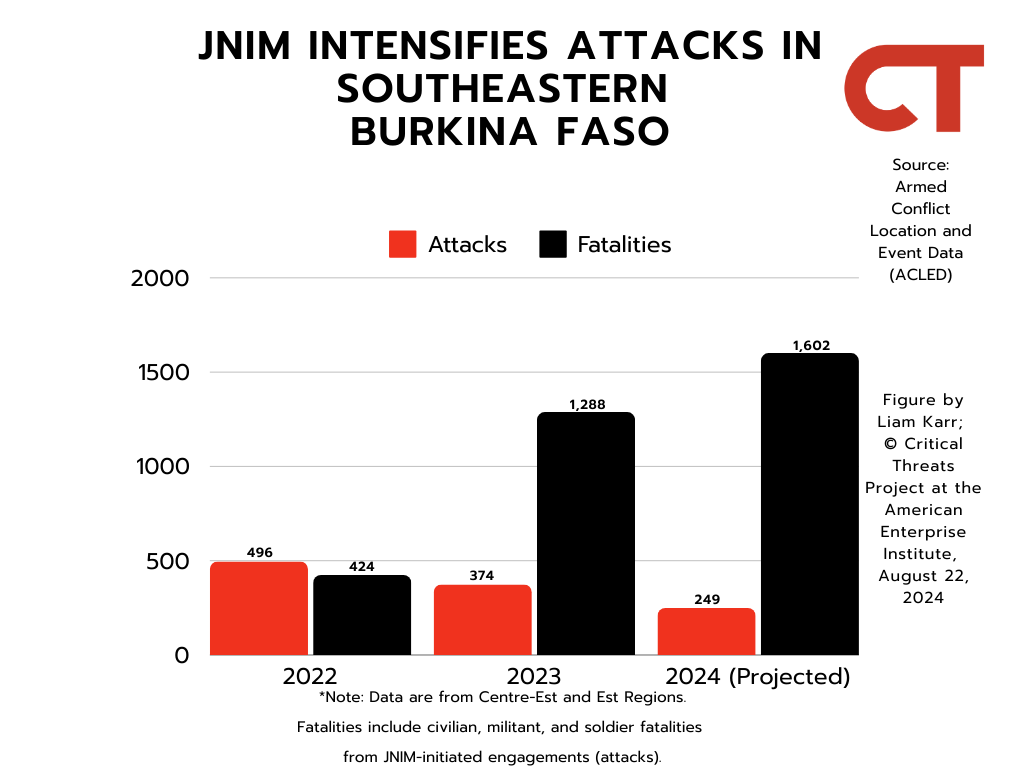

JNIM carried out its deadliest attack ever against Burkinabe forces in early August, which adds to growing internal pressure to overthrow Burkinabe junta leader Ibrahim Traore. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) militants ambushed a Burkinabe military convoy in Burkina Faso’s Est region on August 9.[24] Local media sources claimed that more than 140 Burkinabe soldiers and nearly 50 civilians were killed. JNIM claimed it killed more than 140 Burkinabe soldiers.[25] JNIM claimed the attack was a response to the Burkinabe junta’s alleged crimes against civilians.[26]

The attack is part of an ongoing JNIM campaign that is becoming increasingly deadly as the group targets isolated government-held towns in southeastern Burkina Faso. JNIM is besieging numerous towns—including provincial capitals—around Burkina Faso.[27] JNIM conducts large-scale attacks against large Burkinabe convoys trying to resupply and reinforce these areas and overwhelms weakened and isolated towns as part of this campaign.[28] The group carried out at least three large-scale attacks that killed at least 20 people in eastern Burkina Faso and along the Nigerien border in May.[29] JNIM also conducted a spate of attacks from July 12 to 16 that killed at least 46 civilians.[30]

Figure 1. JNIM Intensifies Attacks in Southeastern Burkina Faso

Note: Data are from Centre-Est and Est Regions. Fatalities include civilian, militant, and soldier fatalities from JNIM-initiated engagement (attacks).

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database Project.

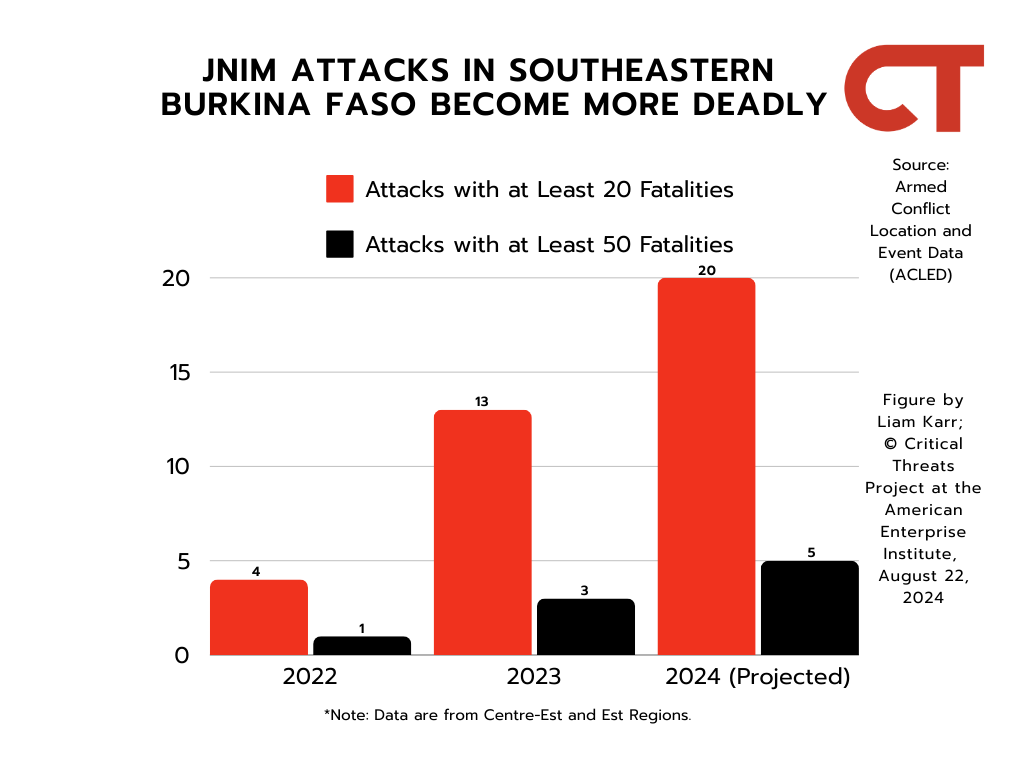

Figure 2. JNIM Attacks in Southeastern Burkina Faso Become More Deadly

Note: Data are from Centre-Est and Est Regions.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database Project.

The attack adds to growing internal pressure to overthrow the Burkinabe junta. The junta survived a potential coup in early June. Soldiers exchanged fire near the presidential palace and national broadcast station on June 12, the day after JNIM killed over 100 Burkinabe soldiers in what had been the deadliest attack on Burkinabe forces.[31] Junta leader Ibrahim Traore disappeared from public over the following week amid rumored talks with discontented segments of the army, and Traore’s Malian and Russian allies sent roughly 100 troops to protect Traore.[32] The Burkinabe junta also claimed to thwart assassination and coup attempts targeting Traore in September 2023 and January 2024.[33]

Large-scale insurgent attacks have contributed to multiple coup attempts in Burkina Faso since 2022. High-casualty militant attacks preceded both successful Burkinabe coups, in January and October 2022.[34] The junta claimed to thwart the September 2023 coup attempt after JNIM killed more than 50 Burkinabe soldiers and civilian auxiliaries in an attack in northern Burkina Faso in early September.[35]

The Burkinabe junta’s focus on regime stability over counterinsurgency operations will reduce pressure on insurgent support zones, enabling the militants to continue carrying out destabilizing large-scale attacks. The Burkinabe junta used the coup concerns in June, including redeploying several elite Rapid Intervention Battalions from their regional bases near insurgent-afflicted areas to the capital on the night of June 19.[36] The arrival of Malian and Russian reinforcements after the June dispute also shows the junta is utilizing the Alliance of Sahel States and its Russian support for regime security rather than joint counterterrorism operations.[37]

JNIM and IS Sahel Province (ISSP) are increasingly conducting large-scale attacks across Burkina Faso, which will prolong internal instability and risk creating more space for insurgents. JNIM and ISSP conducted 43 attacks that killed 20 or more security forces and civilians in the first seven months of 2024.[38] The groups conducted 29 such attacks in 2023.[39] The groups also conducted eight attacks that killed over 50 people in the first seven months of 2024, which is already more than the six such attacks that occurred in 2023.[40] This trend will continue to foment dissatisfaction with the Burkinabe junta, leading to more regime security concerns that will distract from counterinsurgency priorities.