Abstract: Following a U.S. airstrike in Somalia in late May, there were news reports that the Islamic State had appointed Abdulqadir Mumin, the emir of the group’s affiliate in Somalia, as its worldwide leader. The outcome of the airstrike is still unclear. While debates around the accuracy of the reports on Mumin’s promotion continue, the revelation ushers in a unique set of consequential questions regarding the Islamic State’s strategic position and operational priorities. The authors argue that the Islamic State’s reported regional shift in leadership would mark an unprecedented but pragmatic move for the organization. This article presents an overview of Mumin’s background, assesses the Islamic State’s operations during Mumin’s supposed tenure, and situates the analysis within the context of the organization’s traditional approach to leadership.

Recently, news reports claimed that the U.S. military had targeted the global leader of the Islamic State in an airstrike in late May.1 It has not been confirmed that he was killed in the operation. For many, the targeting of another Islamic State leader will feel old hat at this point.2 More interesting is that the reported airstrike occurred in Somalia, marking the first time, presumably, that a top-tier Islamic State leader was found in Africa. Abdulqadir Mumin is already known to the public as the commanding emir of the Islamic State’s operations in Somalia.3 Unnamed U.S. officials claim that he covertly became the “worldwide leader of the terror group” last year.4 a

Typically, when an Islamic State leader is killed, academics and analysts reflexively focus on who will be appointed next, what is known about the successor’s leadership style, and the expected effect on group operations. However, this case raises a more extensive set of questions and related implications.

If true, the selection of an Islamic State “caliph”5 who, one, is not of Arab descent, and two, is based in Africa, would represent a notable change in tack for the terrorist organization. Several counterterrorism analysts and scholars have questioned the accuracy of the reporting6 and speculated that Mumin may have instead been appointed as a ranking operational commander,7 such as the leader of the General Directorate of Provinces (GDP),8 rather than the spiritual and political figurehead of the Islamic State network. Indeed, in many ways, this would reflect a functionally more substantive role while also remaining more consistent with the Islamic State’s strict traditional criteria for its caliph.9

Regardless of the specific title on Mumin’s most recent business card, the reported regional shift in leadership would mark an unprecedented but pragmatic move for the organization. Drawing on their backgrounds in the study of the Islamic State,10 violent extremism in Africa,11 and militant leadership,12 the authors survey the Islamic State’s operations during Mumin’s supposed tenure and analyze this within the broader context of the organization’s long-term approach to leadership and current strategic position.

The Islamic State’s Historic Approach to Leadership

The Islamic State historically has established an elite leadership cadre,13 advanced by the religious authority14 personified by the caliph—the commander of the faithful—and the pragmatic authority15 manifested by the operational experiences of those in functional roles in various directorates.16

The Islamic State’s approach to its caliph is distinct but still rooted in its organizational origins, namely its predecessor groups al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI) and the Islamic State in Iraq (ISI). Both of these organizations strongly emphasized Iraq as a center of gravity. For ISI, this was codified in a January 2007 text, titled Elam al-Anam bi Milad Dawlet al-Islam (Informing the People About the Birth of the State of Islam).17 b Interestingly, and particularly relevant to the skepticism expressed by many regarding Abdulqadir Mumin’s supposed appointment, around this same time there were years of debate and related rumors about the personhood and nationality of ISI’s actual leadership, with the U.S. military claiming initially that the group’s functional emir was not Iraqi Abu Umar al-Baghdadi but Egyptian Abu Hamza al-Muhajir (aka Abu Ayyub al-Masri).18

Since its formation in 2013, the Islamic State has named five caliphs: founder Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, Abu al Hasan al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, Abu al-Hussein al-Husseini al-Qurayshi, and supposed current leader Abu Hafs al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi, who was named in August 2023. In reviewing historical documents provided by the group as well as examining commonalities of caliphs named in publicly available documents, there are at least six core requisite characteristics for those who assume the pinnacle spiritual leadership role of the caliph in the Islamic State: They must be Muslim, male, free, sound in mind and emotion, educated, and of Qurayshi lineage.19 Some primary texts reviewed by Aymenn Al-Tamimi have even indicated that a non-Iraqi would not be favored for the role of the caliph.20

In contrast to al-Qa`ida—an organization most associated with the leadership of its founder Usama bin Ladin—the Islamic State has had a series of leaders of varying notoriety.21 While in recent years these individuals have wielded influence from the shadows, foundational leaders to the Islamic State’s ascension were portrayed in written, audio, and visual messaging.22 Given that the Islamic State’s creative media agency23 constructed life narratives of mythical grandeur, both leaders24 Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi continue to have posthumous appeal despite their deaths marking the end of the era of “known caliphs.”25 Organizationally, the group has been united by the ideological credibility of a central leadership figure, and historically, this person has hailed from and lived in the Iraq and Levant region. Moreover, as recent as 2023, a new Islamic State spokesman addressed “soldiers of the abode of the Caliphate in Iraq and al-Sham,”26 indicating that the geographic region remained central to the core spiritual identity of the group.

As the group has faced intense territorial and leadership loss in Iraq and Syria,27 however, the potential for leaders in other regions may have developed.

While the Islamic State leverages the position of the caliph to provide historical and ideological credibility for the group, a highly bureaucratized structure28 called the General Directorate of Provinces (GDP) affords a variety of leadership styles29 to shape the organization and how it behaves. As recently as June 2023, the U.S. State Department described the GDP function as critical in providing operational guidance and funding around the world for Islamic State activity.30 Based on reporting from the United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team31 and his own review of primary documents from the group, scholar Tore Hamming described key functions of the GDP as well as the likely leaders who have managed them. Some of the functions revolve around the exchange of military expertise and personnel32 among the regional affiliate branches, but the most central function of this hub-and-spoke model is the lifting and shifting of munificence between the core Levant offices and the affiliates. During the height of the group’s power, it was thought that the funding flowed from the central core to regional offices of varying strategic importance, but Caleb Weiss and colleagues have more recently speculated that instead, it is the distant provinces that now often provide cashflow back to the home base as well as to each other.33

The Islamic State’s Al-Karrar office, a key node in the Islamic State’s present financial infrastructure nested within the GDP, is based in Somalia. Aaron Zelin recently described the “global integration” of the Islamic State’s operations, embodied in the GDP.34 In addition to offering operational guidance to affiliates in eastern and central Africa, Al-Karrar serves as a financial hub and transmitter of funds to a number of provinces in other regions. In the Islamic State’s shift toward a regionally pooled financing model, it makes sense that the leader of the Al-Karrar office—being also connected with a prominent regional affiliate—would stand to gain greater power and influence among central leadership.

The Islamic State in the Era of Abdulqadir Mumin

What is known about Abdulqadir Mumin, a leader who not only oversees critical assets in the Islamic State’s network, but also may have built an organization sufficiently wealthy to finance Islamic State operations as far away as the Islamic State Khorasan Province?35

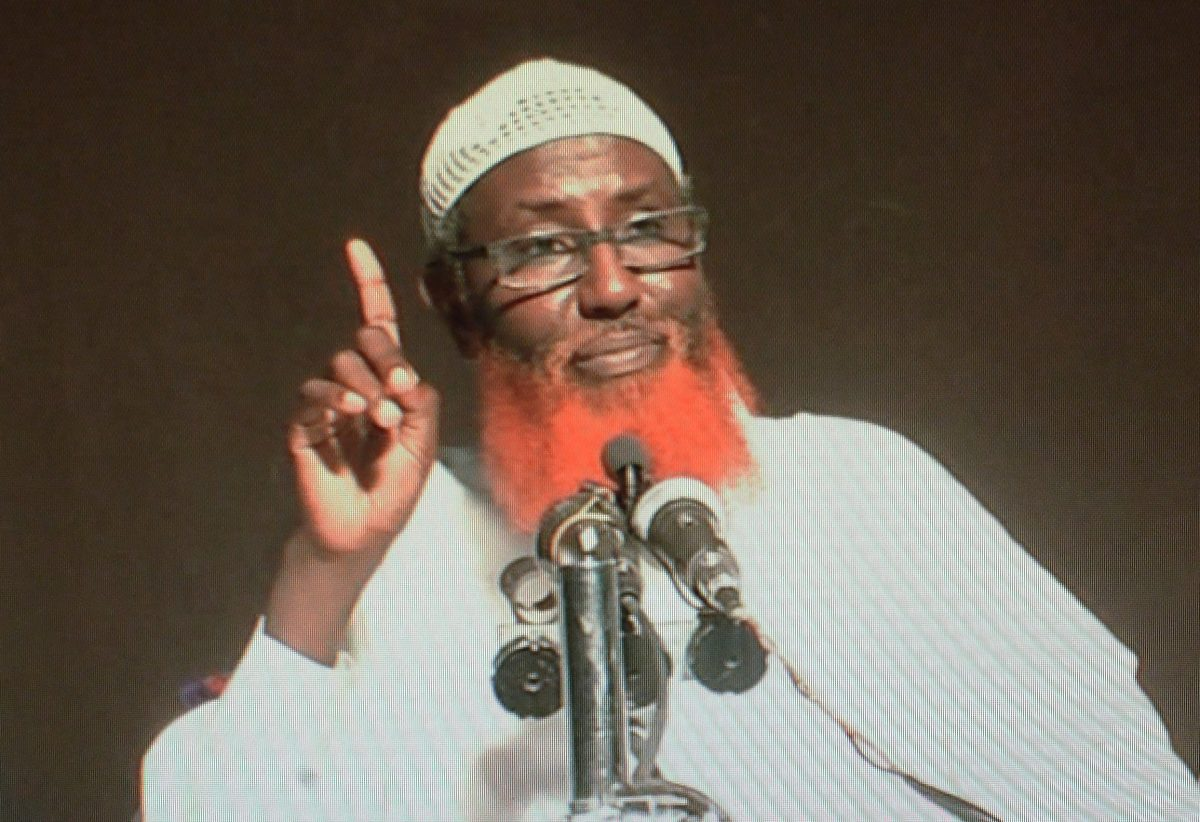

Mumin was born in Puntland, the semiautonomous region in northern Somalia. He lived in Sweden before moving to the United Kingdom in the 2000s, where he was granted British citizenship.36 The few images available of him during this period reveal a joyful countenance, showing a bright henna-dyed beard. The authors speculate that his gleaming white teeth may signal potential early and consistent access to dental care. Swedish scholar Magnus Ranstorp discusses Mumin’s stint in Gothenburg, likely between 1990 and 2003, as a time of increasing radicalization.37 Some have suggested the existence of a clip that was broadcast on Swedish national public television in which Mumin cavalierly discussed the genital mutilation of his daughter.38 After leaving Sweden, Mumin reportedly preached at a mosque in Leicester before moving to South London, where he allegedly crossed paths with Michael Adebolajo (one of the murderers of Fusilier Lee Rigby), Mohamed Emwazi (aka “Jihadi John”), and Moazzam Begg (a former Guantanamo Bay detainee).39 Some reports suggest he was removed from the Greenwich Islamic Center after speculation that he was part of a large recruiting network influencing British men to travel to Somalia and support local violent Islamist network.40 He eventually followed suit and left the United Kingdom for Somalia to join al-Shabaab in mid-2010.41

Later that year, Mumin gained further notoriety after burning his passport in a mosque in Mogadishu, where he was also instructed to find more recruits on behalf of al-Shabaab.42 Mumin became a deputy in the group and, according to scholar Christopher Anzalone, was one of the al-Shabaab officials tasked with negotiating with local clan elders in and around Mogadishu in 2011 to 2012.43 It was during this period that al-Shabaab formally declared allegiance to al-Qaida. Following the surrender of a ranking commander, Mohamed Said Atom, to the Somali government in 2014, Mumin took on a more senior role in the group. And in 2015, he became one of the most notable defections from al-Shabaab to the Islamic State when he pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.44 A small number of his followers joined the Islamic State along with him,45 forming what would become Wilayat al-Sumal (Mumin’s baya was not formally recognized by Islamic State leadership until December 2017).46 The group established its base in the Golis Mountains of the Puntland semi-autonomous region in northern Somalia.47 In 2023, the U.S. Treasury reported that Mumin had become the leader of the Al-Karrar office.48 Under him, his former deputy Abdirahman Fahiye Isse Mohamud was promoted to lead Islamic State-Somalia’s operations as wali (governor).

During Mumin’s tenure, Islamic State-Somalia has experienced up and downs, being pressed hard by both U.S. counterterrorism operations and an al-Shabaab campaign against the group.49 Nonetheless, Islamic State-Somalia has established itself as a niche but prominent member of the Islamic State network.50 Unlike the group’s operational units in Syria and Iraq or the Islamic State West Africa Province, all of which can boast a larger number of combatants and are more active on the battlefield, Islamic State-Somalia maintains a relatively small cadre of fighters. It has staked its reputation less around high-impact attacks or control of large swaths of territory.51 Instead, as host for the Al-Karrar office, Islamic State-Somalia’s gravitas and influence comes through its role as a key node of financial facilitation and operational support to Islamic State affiliates and cells active in central Africa, South Africa, Mozambique, as well as Islamic State elements far outside of the region.52 In the past few months, the group has shown its willingness and occasional ability to repel al-Shabaab forces, though this is still limited to the mountainous areas of Puntland comprising its core base of operations.53

Notably, Mumin developed Islamic State-Somalia into one of the most financially solvent of the Islamic State’s provinces in the post-caliphate era.54 In 2023, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) reported, “In the first half of 2022, ISIS-Somalia generated nearly $2 million by collecting extortion payments from local businesses, related imports, livestock, and agriculture. In 2021, ISIS-Somalia generated an estimated $2.5 million in revenue. ISIS-Somalia is one of the most significant ISIS affiliates in Africa, generating revenue for ISIS to disburse to branches and networks across the continent.”55 In 2024, the U.S. Treasury assessed Islamic State-Somalia to likely be the Islamic State network’s “primary revenue generator,” having earned as estimated $6 million dollars through extortion and taxes since 2022.56 Of course, these numbers pale in comparison to the massive budgets enjoyed by the Islamic State at the height of its territorial campaign; a RAND Corporation report estimates that the group had annual revenues of $1.89 billion in 2014.57 In additional context, al-Shabaab is estimated to bring in annual revenues of $100 million,58 dwarfing its local Islamic State counterpart. Still, present reports indicate that Islamic State-Somalia likely operates at a budget surplus—likely enabled by its historically light operational profile—and, through the Al-Karrar office, is instrumental in moving financial support to Islamic State elements around the region and the globe.

Mumin most likely took his promotion as an Islamic State ‘global leader’ sometime last year. His experience recruiting foreign fighters—particularly those from the West—and his established financial leadership would have been viewed as desirable competencies. The Islamic State’s global operational profile took a somewhat discernible character in the past six to 12 months, which may indicate the priorities or unique efficacies that Mumin brought to the table. First, and most notably, during this period the Islamic State demonstrated an increased willingness and ability to pursue external operations, particularly through its affiliate in Afghanistan, Islamic State Khorasan Province.59 These include a set of deadly operations in Iran60 and Russia.61 Intelligence leaders in the United States warn of a growing risk of similar “coordinated attacks”62 on the U.S. homeland. Second, and relatedly, the Islamic State has continued its emphasis on foreign fighter mobilization63 and inspiring homegrown violent extremist64 attacks in Western Europe, Israel, and North America. Lastly, in 2024, the Islamic State has invested heavily in Africa with a notable show of renewed strength65 in northern Mozambique, recruitment pushes in North Africa,66 and a stubborn entrenchment in Somalia.67 These initiatives align well with what the authors believe to be true of Mumin’s background and experience.

The Organizational Opportunity, Impetus, and Risk of a Leadership Pivot to Africa

If recent reports are correct, what did the Islamic State stand to gain from giving high command to a leader in Africa, in general, and to Mumin, specifically? What were the expected risks that weighed in the decision? Answers to these questions are more than academic; they provide valuable insight into the Islamic State’s strategic priorities and perceptions around its global operational capabilities.

The expected benefits of a regional shift in leadership are an operational commander leading from a seemingly more permissive environment who is also more geographically proximate to the Islamic State’s established and still growing global epicenter of activity.68 One can speculate that the Islamic State likely sought some relief from the heavy operational pressure it faces in Iraq and Syria.69 Due to a steady tempo of high-value targeting operations, the group is on its fourth caliph in less than three years. On the ground, the region remains a hotly contested battlespace and political arena, with several state and non-state armed forces operating in the area, most of which are actively hostile to an estimated 2,500 local Islamic State combatants.70

The Horn of Africa may have offered welcome insulation from instability in the Levant and greater freedom of movement. Of course, as demonstrated in the January 2023 Bilal al-Sudani raid71 and the airstrike in late May, Puntland—the northern region of Somalia in which Islamic State-Somalia primarily operates—is clearly within reach of U.S. forces and their partners.c As such, the relative utility to the Islamic State of a geographic shift in this regard may be only marginal.

Perhaps more importantly, placement in Somalia co-locates the leader with a key facilitation node in the Islamic State network and puts the leader squarely in the region where the group is conducting the most operations, all while retaining connective tissue to the Middle East through Yemen as a transit point for fighters and materiel. To be sure, violence associated with the regional affiliates of the Islamic State has remained somewhat flat over the last year, and the group’s lethality actually decreased in some areas.72 Still, in the global context, violent operations by African branches and cells comprised 60 percent of all claimed Islamic State operations worldwide last year—the largest proportion in the Africa region to date and the sort of portfolio of violence one might expect under the direction of an African emir.73 As senior analysts from the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center recently assessed, “[Islamic State] networks in Africa have the potential to fund and help lead ISIS’ global enterprise.”74

If the benefits of maintaining a top-tier Islamic State leader in Africa are largely operational, the risks for the group are mostly symbolic and reputational, though no less consequential. First, the appointment of a non-Qurayshi as caliph would undermine the group’s carefully laid ideological foundations75 and eschatological vision.76 Mumin has not publicly claimed to be a direct male descendant of the Prophet Mohammad or have Qurayshi lineage.77 This restriction does not apply, however, to heads of Islamic State directorates, such as the GDP. This is where Mumin’s role, his latest formal title, matters most. A blatant inconsistency in this regard would likely provide ample fodder for the group’s competitors and adversaries to launch effective counter-messaging campaigns aimed at undermining the Islamic State’s legitimacy and inciting defections from its corps of followers and supporters. Moving the caliph or other top leadership from Iraq and Syria may also feed into global perceptions around the Islamic State’s failure to survive in Iraq and Syria and the reputational blows it has suffered as a result of its extensive territorial retreat over the past five years.

For the Islamic State, the risks and benefits involved lie not only in regional and organizational dynamics, but also in the appointed leader. Mumin’s background and resumé of experience may reveal the knowledge, skills, and abilities that the Islamic State value at this stage in the organization’s lifecycle and hint at the personal qualities and ‘professional’ competencies that were expected to characterize Mumin’s tenure.

First, Mumin may have come from money—or at least was comfortable with it. Given his life history in Sweden and the United Kingdom, as well as markers evident in his appearance, it may be that Mumin not only was skilled at managing finances in his province and beyond, but he also may have been capable of leading a capital campaign needed to fund a large-scale, international attack. This profile of leadership parallels that of another jihadi leader—Usama bin Ladin—who saw that funding his war was most central to winning it.78

Second, while he may not have had the Qurayshi79 lineage requisite for divine ideological leadership, he clearly would have displayed the spiritual expertise to justify any acts of violence via his interpretation of Islamic law.80 In short, Mumin’s experience as an ideologue in a variety of extremists’ circles likely points to an affluence with leveraging obscure texts and Hadith interpretations that would be difficult to refute or counter. This level of expertise likely made Mumin’s analysis and direction unassailable, particularly by followers with less doctrinal training.

Finally, his familiarity with Western culture likely made him more dangerous than most on at least two fronts: foreign fighter recruitment and attack planning. Mumin had a long record of success in recruiting foreign fighters to Africa, including violent extremists from the Middle East, Europe, and the United States.81 This seems to have proven useful. Recent reports indicate that Islamic State-Somalia has experienced an “influx of fighters and operatives” from Yemen.82 Aaron Zelin reported that in late 2023, four Moroccans were arrested with members of Islamic State-Somalia in Cal Miskaat and, in early 2024, ranking members of Islamic State-Somalia—a Moroccan and a Syrian—were arrested in central Puntland.83 Other foreign fighters have attempted to join the Islamic State’s front in the Sahel.84

Perhaps his most important leadership characteristic had not yet been enacted, however. Given his life events in Sweden and the United Kingdom, it is likely that Mumin would have gained tremendous domain expertise with symbolic people, processes, and property in those and similar countries. In addition, his comfort and familiarity with the media may have made him particularly savvy at timing highly visible and powerful attacks in the West. While there has been an uptick in thwarted plots on such targets,85 none have publicly been attributed to Mumin’s leadership, at least so far.

Conclusions

The geographic shift in Islamic State leadership represented by Abdulqadir Mumin’s reported promotion is probably best understood as a pragmatic recognition of the network’s operational global epicenter, rather than as a signal that the group has reimagined its long-term political and ideological centers of gravity. The Islamic State retains deep roots in Iraq and the greater Levant. And its forces in that region, numbering still in the thousands, remain focused on resurgence.86

The May airstrike in Somalia and related reporting about Mumin’s promotion requires close and sustained attention. Any extensive conclusions will be highly dependent, first and foremost, on whether or not Mumin was actually killed in the operation and, second, on the specifics of his most recent role in the Islamic State. In the meantime, intelligence collection as well as counter-threat efforts should focus on what seem to be the pillars of the Islamic State’s operational priorities during Mumin’s tenure to date, such as an increase in foreign fighter flows to Africa, greater resourcing to African affiliates, and a growing appetite for external operations. The selection of a top tier leader in Africa is notable—for the reasons discussed here—but the rest of the Islamic State’s extensive leadership apparatus almost certainly remains concentrated in the Middle East. In this sense, much is business as usual.

Substantive Notes

[a] The United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team published a report earlier this year that hinted that the Islamic State’s center of gravity may have shifted to Africa: “Several Member States assessed that the level of attrition and security challenges makes a shift in the centre of gravity of ISIL (Da’esh) core away from Iraq or the Syrian Arab Republic possible. Africa and Afghanistan were viable locations for a new leader, with the former more likely.” See “Thirty-third report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2610 (2021) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations Security Council, January 29, 2024.

[b] According to one report, Elam al-Anam “makes the case for Iraq, not by extolling Baghdad’s association with Abbasid grandeur, but by highlighting its strategic location at the center of the Arab world. Iraq also has ample resources that could sustain a new state.” See Nibras Kazimi, “The Caliphate Attempted: Zarqawi’s Ideological Heirs, Their Choice for a Caliph, and the Collapse of Their Self-Styled Islamic State of Iraq,” Hudson Institute, July 1, 2008.

[c] As the authors have written with Tricia Bacon elsewhere, Bilal al-Sudani was a key operative and facilitator for the Islamic State. Like Mumin, the Sudanese national was originally a member of al-Shabaab, where he facilitated the travel of foreign recruits and financed foreign fighter activity in the country. He was designated as a terrorist by the U.S. Treasury Department under E.O. 13224 in 2012 and defected to the Islamic State in 2015. Al-Sudani was killed in a U.S. raid conducted by U.S. military forces in January 2023. See Tricia Bacon and Austin C. Doctor, “The Death of Bilal al-Sudani and Its Impact on Islamic State Operations,” Program on Extremism at George Washington University, March 2023.

Citations

[1] Courtney Kube, “Global leader of ISIS targeted and possibly killed in U.S. airstrike,” NBC News, June 16, 2024; Luis Martinez and Michelle Stoddart, “Top ISIS leader in Somalia was target of US airstrike,” ABC News, June 15, 2024; “U.S. Forces conduct strike targeting ISIS,” United States Africa Command, May 31, 2024.

[2] “Islamic State Confirms Death of Its Leader, Names Replacement,” Voice of America, August 3, 2023.

[3] “State Department Terrorist Designation of Abdiqadir Mumin,” U.S. Department of State, August 31, 2016.

[4] Kube.

[5] Haroro Ingram and Craig Whiteside, “ISIS’s Leadership Crisis,” Foreign Affairs, February 23, 2022.

[6] Carla Babb, Harun Maruf, and Jeff Seldin, “Islamic State in Somalia poses growing threat, US officials say,” Voice of America, June 18, 2024.

[7] Jason Warner, “Is the Islamic State’s Leadership Moving to Africa? Not so Fast,” Modern War Institute, February 16, 2024.

[8] Tore Hamming, “The General Directorate of Provinces: Managing the Islamic State’s Global Network,” CTC Sentinel 16:7 (2023).

[9] Cole Bunzel, “From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State,” Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World 15 (2015).

[10] Craig Whiteside, Charlie Winter, and Haroro J. Ingram, The ISIS Reader (London: Hurst Publishers, 2020); Daniel Milton, “The al-Mawla TIRs: An Analytical Discussion with Cole Bunzel, Haroro Ingram, Gina Ligon, and Craig Whiteside,” CTC Sentinel 13:9 (2020).

[11] Austin Doctor, “After Palma: Assessing the Islamic State’s Position in Northern Mozambique,” Program on Extremism at George Washington, August 2022.

[12] Austin Doctor, Samuel T. Hunter, and Gina S. Ligon, “Militant Leadership and Terrorism in Armed Conflict,” Terrorism and Political Violence 1-17 (2023).

[13] Whiteside, Winter, and Ingram.

[14] Hugh Kennedy, Caliphate: The History of an Idea (New York: Basic Books, 2016).

[15] Haroro J. Ingram and Jon Lewis, “The Founding Fathers of American Jihad,” Program on Extremism at George Washington University and the National Counterterrorism Innovation, Technology, and Education Center, June 2021.

[16] Hamming.

[17] Kazimi; Brian Fishman, “Fourth Generation Governance: Sheikh Tamimi defends the Islamic State of Iraq,“ Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, March 23, 2007.

[18] Bill Roggio, “US and Iraqi forces kill Al Masri and Baghdadi, al Qaeda in Iraq’s top two leaders,” FDD’s Long War Journal, April 19, 2010.

[19] Daniel Milton and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi, “Stepping Out from the Shadows: The Interrogation of the Islamic State’s Future Caliph,” CTC Sentinel 13:9 (2020).

[20] Aymenn Al-Tamimi, “Caliphs of the Shadows: The Islamic State’s Leaders Post-Mawla,” CTC Sentinel 16:8 (2023).

[21] Ibid.

[22] Megan Stubbs-Richardson, Jessica Hubbert, Sierra Nelson, Audrey Reid, Taylor Johnson, Gracyn Young, and Alicia Hopkins, “Not Your Typical Social Media Influencer: Exploring the Who, What, and Where of Islamic State Online Propaganda,” International Journal of Cyber Criminology 14:2 (2020).

[23] Shiroma Silva, “Islamic State: Giant library of group’s online propaganda discovered,” BBC, September 3, 2020.

[24] Haroro J. Ingram and Craig Whiteside, “Generation Killed: The challenges of routinizing global jihad,” War on the Rocks, August 18, 2022.

[25] Al-Tamimi.

[26] Ibid.

[27] “Timeline: the Rise, Spread, and Fall of the Islamic State,” Wilson Center, October 28, 2019.

[28] Michael Logan, Lauren Zimmerman, and Gina S. Ligon, “A Strategic Analysis of Violent Extremist Organizations in the United States Central Command Area of Responsibility,” NSI White Paper (March 2020).

[29] Gina Scott Ligon, Michael K. Logan, and Douglas C. Derrick, “Malevolent Charismatic, Ideological, and Pragmatic Leaders,” in Samuel T. Hunter and Jeffrey Lovelace eds., Extending the Charismatic, Ideological, and Pragmatic Approach to Leadership (New York: Routledge, 2020).

[30] Matthew Miller, “Terrorist Designation of ISIS General Directorate of Provinces Leaders,” U.S. Department of State, June 8, 2023.

[31] See United Nations Security Council, ISIL (Da’esh) & Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Monitoring Team reports.

[32] Warner and Hulme.

[33] Caleb Weiss, Ryan O’Farrell, Tara Candland, and Laren Poole, “Fatal Transaction: The Funding Behind the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province,” Program on Extremism at George Washington University and Bridgeway Foundation, June 2023.

[34] Aaron Y. Zelin, “A Globally Integrated Islamic State,” War on the Rocks, July 15, 2024.

[35] Tricia Bacon and Austin C. Doctor, “The Death of Bilal al-Sudani and Its Impact on Islamic State Operations,” Program on Extremism at George Washington University, March 2023; “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, February 27, 2024.

[36] “Who is this Islamic State’s Abdulqadir Mumin in Somalia?” East African, September 2, 2016; “ISIS-Somalia,” U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, September 2022.

[37] Magnus Ranstorp, Filip Ahlin, Peder Hyllengren, and Magnus Normark, “Mellan salafism och salafistisk jihadism Påverkan mot och utmaningar för det svenska samhället,” Centrum för Asymmetriska Hot- och TerrorismStudier and Försvarshögskolan, 2018.

[38] Louise Lindell, “Nya terrorledaren bodde i Sverige,” Expressen, August 5, 2012.

[39] Duncan Gardham and John Simpson, “Jihadist attended same mosque as Lee Rigby killer,” Times, February 28, 2015.

[40] Jack Moore, “The Orange-Bearded Jihadi General Spreading ISIS Brand in Somalia,” Newsweek, May 24, 2017.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Jason Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three ‘New’ Islamic State Affiliates,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017).

[43] Faisal Ali, “Abdulqadir Mumin as IS caliph would challenge its dogma, says Christopher Anzalone,” Geeska, June 27, 2024.

[44] Thomas Joscelyn, “Shabaab’s leadership fights Islamic State’s attempted expansion in East Africa,” FDD’s Long War Journal, October 26, 2015.

[45] Thomas Joscelyn, “American jihadist reportedly flees al Qaeda’s crackdown in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 8, 2015.

[46] The origins of the Islamic State’s operations in Somalia have been well-documented in the pages of this publication. See, for example, Lucas Webber and Daniele Garofalo, “The Islamic State Somalia Propaganda Coalition’s Regional Language Push,” CTC Sentinel 16:4 (2023); Jason Warner and Charlotte Hulme, “The Islamic State in Africa: Estimating Fighter Numbers in Cells Across the Continent,” CTC Sentinel 11:7 (2018); Caleb Weiss, “Reigniting the Rivalry: The Islamic State in Somalia vs. al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 12:4 (2019); Jason Warner and Caleb Weiss, “A Legitimate Challenger? Assessing the Rivalry between al-Shabaab and the Islamic State in Somalia,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

[47] Zakaria Yusef and Abdul Khalif, “The Islamic State Threat in Somalia’s Puntland State,” International Crisis Group, November 17, 2016.

[48] “Treasury Designates Senior ISIS-Somalia Financier,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 27, 2023.

[49] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State describes intense campaign against Shabaab in northern Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, February 2, 2024.

[50] Warner and Weiss.

[51] Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three ‘New’ Islamic State Affiliates;” Christopher Anzalone, “The Resilience of al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 9:4 (2016); Christopher Anzalone, “From al-Shabab to the Islamic State: The Bay‘a of ‘Abd al-Qadir Mu’min and Its Implications,” Jihadology, October 25, 2015.

[52] Bacon and Doctor; Hamming.

[53] “ISIS breaks out of its Puntland base,” Africa Confidential, June 28, 2024.

[54] Caleb Weiss, “U.S. designates Islamic State financier in Somalia,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 29, 2023.

[55] “Treasury Designates Senior ISIS-Somalia Financier,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, July 27, 2023.

[56] “Fact Sheet: Countering ISIS Financing.”

[57] Patrick B. Johnson, Mona Alami, Colin Clarke, and Howard J. Shatz, “Return and Expand? The Finances and Prospects of the Islamic State After the Caliphate,” RAND Corporation, 2019.

[58] “Letter dated 23 January 2024 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011) and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals, groups, undertakings and entities addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team, January 29, 2024.

[59] Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Lucas Webber, and Riccardo Valle, “From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024).

[60] Parisa Hafezi, Elwely Elwelly, and Clauda Tanios, “Islamic State claims responsibility for deadly Iran attack, Tehran vows revenge,” Reuters, January 4, 2024.

[61] Sara Harmouch and Amira Jadoon, “How Moscow terror attack fits ISIS-K strategy to widen agenda, take fight to its perceived enemies,” Clemson News, March 25, 2024.

[62] Jeff Seldin, “FBI fears ‘coordinated attack’ on US homeland,” Voice of America, April 11, 2024.

[63] Aaron Y. Zelin, “The Islamic State on the March in Africa,” Washington Institute, March 1, 2024.

[64] Jeff Seldin, “Terror attacks headline threats to upcoming Paris Olympics,” Voice of America, June 4, 2024.

[65] Tom Gould and Gerald Imray, “New attacks by IS-linked group in Mozambique leave over 70 children missing. Thousands have fled,” Associated Press, March 6, 2024.

[66] Zelin.

[67] Babb, Maruf, and Seldin.

[68] Tricia Bacon, Austin C. Doctor, and Jason Warner, “A Global Strategy to Address the Islamic State in Africa,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, June 29, 2022.

[69] “Iraqi forces kill senior Islamic State leader in a raid on Syria,” Reuters, June 11, 2024.

[70] Jeff Seldin, “Worrying signs exist that IS growing stronger in Syria,” Voice of America, April 5, 2024.

[71] Bacon and Doctor; Eric Schmitt, “Ties to Kabul Bombing Put ISIS Leader in Somalia in U.S. Cross Hairs,” New York Times, February 4, 2023.

[72] “Deaths Linked to Militant Islamist Violence in Africa Continue to Spiral,” Africa Center for Security Studies, January 29, 2024.

[73] Mina al-Lami, “What happened to IS in 2023?” BBC Monitoring, December 26, 2023.

[74] NCTC’s Senior Analysts, “Calibrated Counterterrorism: Actively Suppressing International Terrorism,” CTC Sentinel 16:8 (2023).

[75] Haroro J. Ingram, “The Long Jihad,” Program on Extremism at George Washington, 2021.

[76] Graeme Wood, “What ISIS Really Wants,” Atlantic, March 2015.

[77] Ali.

[78] Deb Riechmann and Robert Burns, “Osama bin Laden wanted the bulk of his fortune used ’on jihad,’” PBS News, March 1, 2016.

[79] Milton and al-`Ubaydi.

[80] Ian R. Pelletier, Leif Lundmark, Rachel Gardner, Gina Scott Ligon, and Ramazan Kilinc, “Why ISIS’s message resonates: Leveraging Islam, sociopolitical catalysts, and adaptive messaging,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 39:10 (2016).

[81] “The Islamic State in East Africa,” European Institute of Peace, September 2018.

[82] Babb, Maruf, and Seldin.

[83] Zelin.

[84] Liam Karr, “Foreign Fighters and Jihadi Rivalry in the Sahel; Somalia Backslides,” Institute for the Study of War, March 14, 2024.

[85] NCTC’s Senior Analysts; “Germany charges seven suspected ISIS-K members over attack plots,” Reuters, April 24, 2024; Petter Nesser and Wassim Nasr, “The Threat Matric Facing the Paris Olympics,” CTC Sentinel 17:6 (2024).

[86] Jeff Seldin, “US fears Islamic State comeback in Syria, Iraq,” VOA News, July 17, 2024; “Defeat ISIS Mission in Iraq and Syria for January – June 2024,” U.S. Central Command, July 16, 2024.