Libya’s climate-vulnerable regions of Jabal Nafusa, Fezzan, and Jabal Akhdar underscore the important role played by civil society and municipalities in protecting marginalized communities.

A vast, arid, oil-dependent country of nearly 7 million people, Libya is acutely exposed to the deleterious effects of climate change. These problems include soaring temperatures, declining rainfall, rising sea levels, extended droughts, and sand and dust storms of increasing frequency, duration, and intensity, to name a few. The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index ranks Libya 126 of 182 states, just after Iraq, in the lower-middle tier denoting most vulnerable countries.

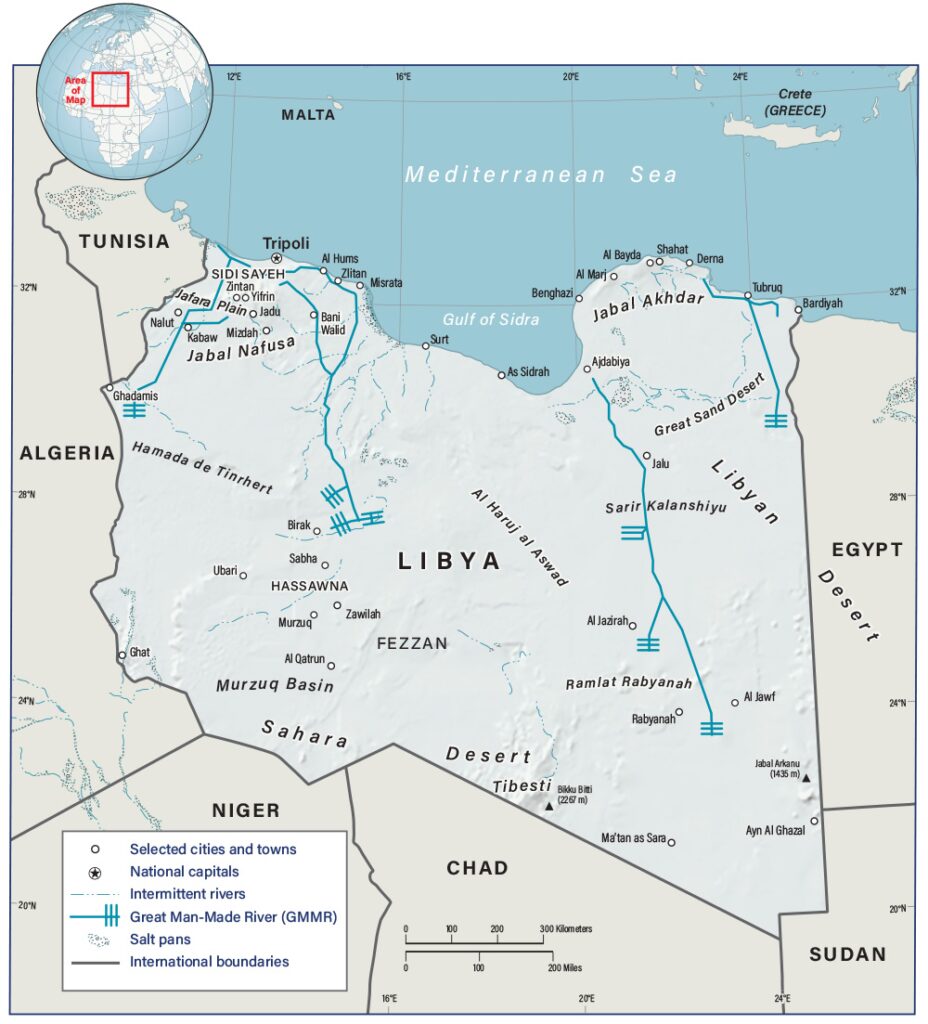

The diminishing availability of water is Libya’s most pressing climate-related risk. Eighty percent of the country’s potable water supply is drawn from nonreplenishable fossil aquifers through a network of pipes known as the Great Man-Made River (GMMR), which suffers from deteriorating infrastructure, evaporation in open reservoirs, unsustainable extraction rates, and uneven service to Libya’s far-flung towns. The lack of a national water strategy or integrated water policy, along with heavily subsidized water tariffs, has further exacerbated the effects of this scarcity. The provision of clean water increasingly has become a source of regional, communal, and political competition. Electricity is similarly threatened by climate disruptions, particularly temperature spikes, due in no small part again to eroding infrastructure and heavy subsidization, which contributes to exorbitant consumption rates and outages.

Oil dependence is yet another vulnerability. Libya, which has the largest proven reserves in Africa, has long relied on oil exports as its primary source of revenue. This pattern of reliance has resulted in a disproportionately large public sector, which employs 85 percent of the population and leaves the country severely exposed to future declines in oil prices caused by the transition to renewable energy and net-zero carbon pledges. Oil is also used to generate electricity, which is not only costly but contributes—along with the wasteful “flaring” or venting of gas during oil production—to Libya having the highest per-capita carbon emission rate in Africa.

At the height of the dictator Muammar Qaddafi’s ambitions, arable land comprised only 1.2 percent of the country’s territory and has since shrunk to less than 1 percent. The agricultural sector itself has been contracting steadily since the 2011 revolution, owing to the cumulative effects of conflict, supply chain disruptions, rising costs of agricultural supplies, and the lack of renewable water supplies. And while it contributes to a miniscule portion of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), estimated at less than 2 percent in 2022, the agriculture sector continues to be a source of income for a not-insubstantial percentage of its inhabitants—estimated at 22 percent in 2020. Libya’s low agricultural output means that it is forced to import three-quarters of its foodstuffs, making the country extremely vulnerable to disruptions in global food supplies, including those resulting from climate change. Endemic government inattention to the agricultural sector has only worsened this dynamic. “They don’t prioritize it because they think it doesn’t contribute to the gross income,” noted a Libyan soil scientist in a telephone interview. “But if we lose local food production, we have food insecurity.”1

These vulnerabilities present an especially dire threat to the well-being and human security of people living in the sparsely populated regions of the Jabal Nafusa (Nafusa Mountains), also known as Jabal Gharbi, west of Tripoli; the southern Fezzan region; and the Jabal Akhdar (Green Mountains) in eastern Libya (see map 1). Here, climate shocks are being aggravated not only by environmental degradation but also by socioeconomic marginalization, political and intercommunal conflicts, and collapsing infrastructure. The cumulative impacts of these factors on food security and subsistence farming are a particular concern in these three areas, given that the Jabal Akhdar region produces half of all of Libya’s crops and the Jabal Nafusa region, its adjacent Jafara Plain, and the Fezzan grow the other half. Farmers interviewed in these regions were acutely aware of how climate change combines with political and socioeconomic problems, especially poor governance, to threaten their livelihood.

“The main factor is neglect,” noted one farmer in the Sidi Sayeh area south of Tripoli. “There is no oversight, no support, no investment in growing our capacity as farmers. Climate change adds another layer, but it is the juxtaposition of its effects with the lack of institutional oversight and support that will push farmers like me to leave behind their ancestral practices.”2

It is not only farmers who are threatened in these areas. Migrants and refugees are especially at risk, given the proximity of some of these agricultural areas to borders and their resultant role in hosting displaced persons. So too are Libyan ethnolinguistic minorities, for whom climate change compounds preexisting grievances of discrimination. Workers in the informal sector, women, and children are also imperiled.

Understanding how climate change is affecting the well-being and livelihood of these at-risk populations is therefore essential for the crafting of a viable, more inclusive climate strategy, one that mobilizes local resources and knowledge to build better pathways for resilience—for all of Libya’s inhabitants.

The Climate-Governance-Misgovernance Nexus in Libya

Long-standing problems of governance, institutional fragmentation, political tensions, and recurring armed conflict have sharpened Libya’s vulnerability to climate change and also impeded a coherent government response to climate mitigation and adaptation.

The roots of the country’s climate fragility are found in Qaddafi’s poor management of resources and inefficient state-owned monopolies managing water and electricity. Added to this were Qaddafi’s overly ambitious agricultural schemes that saw the rapid depletion of coastal aquifers and a dependence on his much-touted megaproject, the GMMR. He often used the project politically, prioritizing access for favored communities and excluding others who were deemed less loyal. His peculiar brand of socialist rule oversaw the collectivization of land in the mid-1980s, a process that removed existing legal safeguards on nature preserves and hastened the deforestation of the Green Belt around Tripoli and other cities, which for decades had contributed to a beneficial microclimate, slowed desertification, and stopped soil erosion.3

Since Qaddafi’s death in 2011, a worsening spiral of factional conflict, corruption, infrastructural decay, and predation has left ever-greater numbers of people exposed to climate shocks. The chaos has also produced a profound lag in the country’s official response to climate change. Of the 196 signatories to the 2016 Paris Agreement, only Libya has not signed a Nationally Determined Contribution. And even though the country has established a renewable energy plan and has enormous potential for solar and wind energy, it has made little progress on these fronts, in part because of a lack of competitiveness in the private sector and bureaucratic resistance from state-owned monopolies.

Political fissures and elite rivalries are in no small measure to blame for this paralysis. The country is nominally ruled by a Government of National Unity (GNU), but in practice it is split between the Tripoli-based administration and Khalifa Haftar’s increasingly militarized administration in the east. Despite some climate-related cooperation and exchange of information, this split continues to hobble progress. Even within the GNU, there has been competition over control of climate policy, most evident between the Ministry of the Environment and a climate authority within the prime minister’s office—though the two bodies have reportedly improved their collaboration and coordination.4

Increasingly, key ministries and institutions have been taken over by armed groups, in both the east and west, which have further contributed to climate vulnerability through environmental predation, converting tracts of forests into more profitable money-laundering schemes like apartments, malls, and resorts, while also selling chopped-down trees as charcoal.5 The effects of such predation, particularly acute in the western Jafara Plain and in the eastern Jabal Akhdar, have only worsened the effects of climate change, particularly for those Libyan citizens who make a living off the land. “The consequences of climate change became more acute ever since they started breaking down the forests into smaller units, cutting the trees, and selling off the land,” noted a farmer in the southern environs of Tripoli.6 And although the agricultural police department that operates in both the east and west has publicized its crackdown on illegal clearing, it does not cross the red lines of dominant armed groups.

Elsewhere, Libya’s ability to build climate policy is hobbled by a dearth of qualified personnel, insufficient technical capacity, poor local data collection, poor collaboration between the government and universities, and a lack of local-level participation and activism.7 Libyan municipalities in particular have important roles to play on climate change advocacy and awareness, but they have been frustrated by a lack of administrative, budgetary, and political support from the capital.8 Libya’s civil society is similarly constrained by a lack of support and increasingly repressive security measures from authorities in both the east and the west. This lack of support has had a chilling effect on climate activists.

These daunting structural and political problems will have profoundly negative consequences for the country’s ability to surmount the challenges of climate change—and they are felt acutely in the mountainous zone just west of the capital.

The Jabal Nafusa

Rising to 900 meters above sea level (nearly 3,000 feet), the Jabal Nafusa are a rugged mountainous plateau that arcs around the Jafara plain west of Tripoli and stretches over 400 kilometers (about 250 miles) to the Tunisian border. Historically, the region has been of marginal political and strategic significance, though this changed with the 2011 revolution, given the range’s role as a base for anti-Qaddafi rebels and its location alongside routes into the capital. The divisions within the Nafusa region that emerged during that period—as some towns supported the uprising and others opposed it—reflected in many instances the Qaddafi regime’s exploitation of intercommunal tensions by granting favored communities grazing land, employment in the security services, and even access to water.

Roughly speaking, the most prominent division today in the region is an ethnolinguistic one between Arab communities, who historically were pastoralists, and the Amazigh people, who were predominately settled farmers (hadhar). That said, neither the Amazigh nor the Arab communities in the Nafusa region behave today as a monolithic bloc: allegiances and alliances among their respective towns often straddle the ethnolinguistic line and are constantly shifting. Against this backdrop of fragmentation, climate change and its attendant worsening of water shortages has sharpened intercommunal tensions in the Nafusa region and tensions between Nafusa communities and the Tripoli government.

Historically farmed since antiquity, the eastern portions of the Nafusa range are the most fertile and productive, particularly for the cultivation of olive, fig, and almond trees. And even though the region has always grappled with droughts, sandstorms, and erratic rainfall, anthropogenic climate change and global warming are causing a different sort of threat.9 Local farmers have noticed that winters are getting warmer while summers have become drier and hotter, without the usual cooling-off in the evening, leading to outbreaks of wildfires that required the dispatch of firefighting equipment from outside the country. Rainfall appears less frequently, and sandstorms are changing in seasonality and increasing in intensity, the result of both global warming and local factors such as declining plant cover and soil erosion.10 Desertification—a direct result of climate change—is increasing as well, with expanding sand reducing the area of cultivable land (see figure 1).

The impact of these stressors has been magnified by the aforementioned inefficiencies in water supply and political marginalization. Qaddafi’s historical mistrust and suppression of the Amazigh people led him to deny predominantly Amazigh towns in the Nafusa region access to the GMMR network, forcing a reliance on wells and water tanks that continues to this day. The GMMR’s discontinuity continues to plague the predominately Amazigh towns of Yifren, Nalut, Jadu, and Qala’a, as well as some Arab towns like Zintan, which was scheduled to be connected to the pipeline system before the 2011 revolution interrupted that work. Consequently, a significant number of Nafusa communities have been forced to rely on water shipments delivered by tanker trucks. But these trucks, which haul water up steep mountain roads from a reservoir at the base of the Jabal Nafusa, are too few in number to service the entire region and often are prohibitively expensive for many families. Accessing deep groundwater aquifers through excavation and well-digging is another option, but this too is a costly and often unsuccessful endeavor. Moreover, wells in some locales often are too few to cover the population’s needs or have fallen into disrepair (see figure 2). Even in communities that the GMMR reaches, the water supply is often limited and inconsistent.

In the face of such infrastructural and climate challenges, some Amazigh communities in Nafusa have taken to reviving ancestral adaptation and stewardship mechanisms including agroforestry, terracing techniques, and water management practices. One such method, agdal, is a communal approach to land utilization characterized by the cyclic utilization of grazing areas, a mindful approach to water consumption that prioritizes sustainable sustenance, and, most importantly, a profound set of social and ethical principles centered around the responsible management of fertile and water-abundant lands. Traditional customs like agdal enable Amazigh communities to gather and preserve water during the rainy seasons and thrive amid challenging environmental circumstances.

Elsewhere, municipal leaders in Nafusa are leading grassroots efforts on climate adaptation, focusing on rationalizing water and electricity consumption and combating desertification. They are pushing for greater local empowerment while soliciting services from the GNU in Tripoli and support from foreign states and donors. But such efforts remain hampered by meager budgets from authorities in the capital. In one notable case, the mayors of three Nafusa towns—Jadu, Yifren, and Kabaw—reportedly diverted the 150,000 dinar allotment from the Tripoli government for the purchase of an official car to fund environmental services and to address their towns’ water scarcity problems. More broadly, though, municipalities suffer from Libya’s aforementioned lack of political and fiscal decentralization, a shortcoming acutely felt by people in other parts of the country grappling with climate change, especially those in Libya’s underdeveloped desert south.

Fezzan

The southwest region of Fezzan, stretching over 200,000 square kilometers (nearly 125,000 square miles), is Libya’s driest, hottest, and most inhospitable area, marked by a Saharan topography of sand dune seas, gravel-strewn plateaus, volcanic mountains, dry riverbeds, and oasis depressions. Climate change is thus a particular concern for its inhabitants. As it has been for millennia, water continues to be a prized and contested commodity in this region, evident in Fezzan’s role in supplying the aquifer-fed water to the GMMR pipeline, a quality that has only grown in importance as Libya’s northern groundwater supplies are depleted by salinization. Water has also aggravated a deepening sense of socioeconomic exclusion by Fezzan’s inhabitants, who comprise 10 percent of Libya’s population.

Today, Fezzan is Libya’s poorest region, even though it is home to important oil fields that produce one-quarter of the country’s total crude output. Though Qaddafi set up thousands of hectares of state-owned farms in the south, the infrastructure has fallen into disrepair since the 2011 revolution. Moreover, the Qaddafi regime rewarded favored Arab tribes with preferential access to the smuggling trade and other privileges and marginalized non-Arab ethnolinguistic minorities, such as the Tabu and the Tuareg. The Tuareg, however, were slightly better off because they had been included in the security services and had access to agricultural land.11

Those disparities are felt today in outbreaks of violent conflict between and within these groups, often over access to increasingly important fixed economic streams derived from the cross-border smuggling of people and goods as well as access to the region’s oil fields. Climate change, with its attendant effects of water scarcity, expanding desertification, and extended droughts, will further inflame these fissures and also amplify the grievances the people of Fezzan feel toward the north. Already, Fezzan’s importance as a source of water has been leveraged as a means of conveying those grievances, with tribes and protesters dismantling or otherwise sabotaging pumps along the GMMR network, at one point at a rate of four pumps per month.12 In the vital Hassawna area of Fezzan, which supplies Libya with 60 percent of its water, vandalism of wells diminished water output by over 30 percent, causing shortages in the north. Rapidly diminishing groundwater is yet another problem, especially in the Murzuq Basin, where a major aquifer provides water to towns and farms in the southwest portion of Fezzan not connected to the GMMR. According to one projection, the aquifer may be depleted as soon as 2037, causing severe socioeconomic damage throughout the area.13

In the Tuareg and Tabu communities of the south, the perception of municipal neglect is magnified by deeply entrenched feelings of ethnolinguistic discrimination by Arab elites in the north. In the southwest municipality of Ubari, for example—home to substantial agricultural land and Libya’s largest oil field, and the site of fierce intercommunal and political conflict from 2014 to 2016—Tuareg residents have long complained about the diversion of water and petroleum wealth to the north. Some believe that this diversion, and the attendant exodus of youth from the region, will pose an existential crisis for their survival as a distinct minority.14 “The Tuareg will disappear,” noted one Tuareg activist from the area, who served as a former deputy minister of water. He described a proposal by a young local Tuareg engineer to purify sewage water and use drip-irrigation to cultivate a tree line from Ubari to Sabha in order to counter desertification without endangering future water access. “As long as there are people there is sewage, so it is sustainable,” he maintained.15 But the engineer’s plan remained unrealized, he stated, owing to a lack of support from Tripoli.

The effects of water scarcity, compounded by climate change, will disproportionately affect Fezzan’s most vulnerable inhabitants. Even with the deterioration of agriculture infrastructure through conflict, theft, and neglect since 2011, many still depend on farming for their livelihood. Displaced persons and migrants—whose numbers in Fezzan are likely to grow in the face of climate shocks and slow-onset climate pressures—are especially reliant on agricultural work, sometimes in forced labor conditions under armed groups and smugglers.16 Though men provide the primary labor, women often assist in the rearing of livestock, and children under the age of sixteen provide farming labor, especially during school vacations. Given its remoteness, the south also faces challenges of transporting crops to northern markets. Road networks are especially vulnerable to worsening sandstorms, which raise transportation costs.17

Throughout Fezzan, there are often fruitful exchanges between private and public entities in towns and cities. One such meeting took place at a workshop on the challenges and prospects of sustainable development in southern Libya, convened in February 2023 between Tripoli University, Sebha University, Sahara and Sahel Observatory, and the Libyan Center for Studies & Researches for Environmental Science and Technology. An agricultural research center in the northern coastal city of Misrata, as another example, is teaching farmers in the south to grow crops using less water and to use water with greater salinity, while also introducing newer, more durable seed varieties that are better adapted to the increasingly arid conditions.18

Even with these indicators of progress, municipal officials in Fezzan have complained vociferously about the lack of appropriate central government legislation, authorization, and funding, which would empower them to act as agents for climate adaptation rather than simply as providers of services such as water and waste removal.19 They also face outmoded laws that prohibit direct interaction with foreign companies and officials, which prevent them from obtaining outside expertise and equipment. Partly as a result, local-level efforts to harness the region’s great potential in solar and wind remain sporadic and unrealized.

These same concerns about sustainability in the face of government inertia are also present in Libya’s third climate-affected periphery, the mountains of the east, where historically abundant rainfall is rapidly diminishing.

The Jabal Akhdar

With its thickly forested slopes and bucolic meadows, the aptly named Jabal Akhdar seem a world away from Fezzan. Rising 800 meters above sea level (about 2,600 feet) and stretching350 kilometers (about 215 miles) from Benghazi in the south to Derna in the north, the mountains are Libya’s wettest region and home to its densest concentration of trees and its most arable land. It is also rich in biodiversity: though it constitutes just 1 percent of Libya’s surface area, Jabal Akhdar accounts for anywhere from 50 to 75 percent of its plant species, leading one climate activist from the area to dub the mountains and their forests “the lung of Libya.”

Though its populace lacks significant communal divides, the mountains have been the site of political instability and grievances against the government, especially given eastern Libya’s perception of relative decline after Qaddafi’s 1969 coup toppled the eastern-based Senussi dynasty. During the 1990s, these grievances informed a fierce Islamist insurgency against the regime that used the fortress-like gorges and caves of the Jabal Akhdar as a haven. Since the fall of Qaddafi, successive rounds of violence in eastern Libya, particularly during the 2014–2018 war that wracked Benghazi and Derna, only worsened the region’s environmental deterioration and vulnerability to climate change.

Today, the region is firmly under the control of Haftar and his Libyan Arab Armed Forces (LAAF), who are nominally part of the GNU in Tripoli but who in practice govern eastern Libya as a separate administrative territory. Although Tripoli and the east have working-level coordination and collaboration on some issues, such as meteorological data collection and the exchange of research on seed varieties, steps toward more national-level climate cooperation invariably fall victim to the same elite rivalries and factionalism that plague other aspects of Libya’s governance.20 Simultaneously, Haftar’s kleptocratic rule is exacting a severe toll on environmental protection in the Jabal region. Nowhere is this more evident than in the activities of the LAAF Military Investment Authority. This organization is a profit-making enterprise for the Haftar family and has been involved in predatory illicit enterprises such as fuel smuggling and scrap metal harvesting. Reportedly, some of the illegally acquired scrap metal (which often is sold abroad) comes from equipment and components of the GMMR.

The inhabitants of the Jabal Akhdar acutely feel the nexus of governance, climate change, and environmental devastation. As elsewhere, farmers in the area suffered from problems like electrical outages, supply chain disruptions (particularly seeds), rising costs of drilling for groundwater, and soil erosion caused by overgrazing and poor land management. All of these issues have been compounded by climate-induced temperature spikes and declining rainfall.21 Furthermore, the region’s beekeepers—a niche but important industry, especially in the east, where honey is particularly prized for delicacies and traditional remedies—have seen their honey output decline drastically as climate change has pushed temperatures to ranges that are inhospitable for bees.

But the most catastrophic environmental affliction in the mountains is the rampant loss of tree and vegetation cover. Between 2005 and 2019, the Jabal Akhdar lost over 14,000 hectares of forest, with the rate of deforestation accelerating after 2011 as insecurity and lawlessness encouraged people to sell wood for charcoal and to embark on unchecked construction. Government efforts to crack down on such illegal practices have been uneven, with better-armed militias and criminal groups sometimes responding to enforcement efforts with heavy gunfire. Conflicts in the east and elsewhere have also exacerbated deforestation as urban areas have expanded and new settlements have emerged to accommodate displaced persons.22

Regardless of reason, the effects of deforestation have been uniformly harmful for citizens’ livelihoods, health, and properties. Deprived of tree cover, the average mean temperature in the area has risen, which in turn has made outbreaks of wildfires more likely. Already, soaring heat waves have sparked outbreaks of such destructive blazes, like the ones in 2013 and 2021 that swept through forests near Shahat and Al-Bayda, respectively. The absence of tree cover has also contributed to soil erosion and decreased agricultural outputs, while also increasing the prevalence of dust storms originating from the region.23

More broadly, the human-caused transformation of the region’s natural environment, along with widespread corruption and decaying infrastructure, has worsened the damage from climate-induced floods like those that hit the eastern city of Al-Bayda in late 2020, displacing thousands. Most tragically, the city of Derna at the foothills of the Jabal Akhdar suffered a catastrophic loss of life—an estimated at 11,200 people—after two aging dams collapsed during Storm Daniel in early September 2023. The same storm also displaced more than 40,000 people from Derna and other locales. The impact of Storm Daniel underscores how the malignant effects of politics and militia rule magnify climate shocks in Libya: in the case of Derna, Haftar’s military regime had long targeted and isolated the town because it had a history of opposition to his authority. This animosity contributed to the municipality’s unpreparedness and to the storm’s staggering death toll.

The aftermath of the Derna tragedy has made it clear that local actors need to have both the capacity and the freedom to tackle climate adaptation and environmental stewardship. Municipalities in and around the Jabal Akhdar, as elsewhere, have taken some commendable steps on these fronts, with campaigns on water rationalization, well-digging, recycling drives, electricity conservation, and other actions toward sustainability. On the crucial problem of deforestation, local civil society, journalists, and bloggers have been especially active. Reforestation initiatives in particular have proven enormously popular, with groups like the Libyan Wildlife Trust and the Boy Scouts planting millions of seedlings and sponsoring awareness campaigns in schools. Yet according to several observers, these efforts, while laudable, are not enough: Libyan civil society has not yet been able to realize its full potential as a bridge between the public and private sectors and as a voice for vulnerable communities.24 The activists themselves admit that their efforts cannot keep pace with environmental devastation, and they point to the need for a better-equipped and more robust response from official law enforcement entities.

Moreover, in the east in particular, activists face restrictions from the area’s security forces. Though these forces do not directly target environmental and climate groups as long as their activities do not cross certain political red lines (like corruption or the role of the Haftar family), their presence still has a chilling effect.25 “Young people are willing, but they are afraid,” noted one official from the region. “There is no state support.”26 In a September 2023 interview, a member of a volunteer climate action group in eastern Libya gave an example of such interference, stating that their organization’s efforts to import weather monitoring equipment—to compensate for what this person believed was the inadequacy of the official meteorological service—were blocked by Haftar’s government because of supposed security concerns.27

Relatedly, policing bodies in both the east and the west often have a distinctly ideological bent deriving from the Salafi current of Islam, evident in arrests that are not rooted in codified law but rather are against transgressions deemed to be un-Islamic. These arrests have included crackdowns on environmental activism like an “Earth Hour” event in Benghazi in 2017 and, more recently, in the arrests of animal rights defenders in the same city. In such an environment, it is not surprising that many climate activists operate from abroad or solely in the virtual space, while others confine their engagement to politically “safe” activities. Separately, Haftar’s governing apparatus could try to coopt climate action as a form of legitimation, or greenwashing—especially as the issue attracts great funding and support from outside donors. Arab autocrats elsewhere have pursued similar tactics by focusing mostly on technical solutions, renewable energy plans, and ambitious net-zero pledges while sidelining the society-focused governance reforms and grassroots partnerships that effective climate adaptation requires.28 The urgency of such local-focused reforms is nowhere as apparent as in Libya’s vulnerable peripheral regions.

Conclusion: Building Grassroots Climate Resilience in Vulnerable Regions

The sheer scale of Libya’s climate fragility demands a radical departure from the status quo. In many respects, climate change accelerates and amplifies preexisting deficiencies in governance and inequalities that predate the chaos of the 2011 uprising and its aftermath. It also introduces new shocks, like heat waves, fires, and extended droughts. These impacts are worsening the health and livelihood of already at-risk populations—those in the agricultural sector, for instance—while creating new stresses on comparatively better-off citizens.

Endemic insecurity and successive rounds of national-level internal conflict starting in 2014 have understandably impeded concerted climate and environmental action by governments and citizens alike. “It’s hard to garner public support for trees when people’s lives are in danger,” admitted an environmental activist in 2013. But the peace that has emerged since a United Nations–brokered ceasefire in 2020 is one in which armed groups dominate the political and economic life of the country as dynasties of venal elites in both east and west carve up the spoils while stifling free expression and civil society. Such circumstances are hardly cause for optimism on climate adaptation.

At the most basic level, that adaptation should prioritize solving Libya’s water crisis by extending the GMMR to communities in need, halting the decay of its infrastructure, and rationalizing the use of the water it delivers. Among consumers, this rationalization can be accomplished principally through tariffs. Farmers can support the process through more efficient practices like the introduction of new seed varieties, a shift toward less water-intensive crops, and more sustainable techniques like hydroponic farming. In tandem, Libya should explore alternate sources of freshwater, like desalinization. Today, most of Libya’s sixty desalination facilities are not operational, and the industry itself faces a lack of support owing to these maintenance issues and perception of its prohibitive cost. Yet with the rapid depletion of the country’s aquifers, that perception needs to change. Various innovative domestic proposals have been advanced for making desalinization in Libya more economically feasible; one proposal advanced by a Tuareg activist and former official would use dune-generated heat in Fezzan to power coastal desalinization plants.29 Underpinning all these potential options is the pressing need for a national water strategy and an integrated water policy that will rationalize and safeguard its distribution across the sprawling country.

That need, in turn, speaks to another urgent imperative for Libya’s climate adaptation: vision and will at the top. As noted, the challenge of fiscal and political decentralization in Libya is deeply entrenched. On climate change, municipalities are hindered by legal and funding restrictions, such as the lack of legislative empowerment to tackle climate adaptation and the need to seek preapproval for revenue expenditure instead of having climate change measures built into their budgets.30 Beyond this consideration, municipalities need greater authority and leeway and fewer bureaucratic obstacles to expeditiously access foreign funding, equipment, and expertise, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Taqarib project and the European Union’s Tamsall effort. For their part, both the Libyan government and foreign donors should work to coordinate and “bundle” municipal-level projects, more efficiently identify best practices, more easily access outside funding, and scale-up successes.

Beyond town-level empowerment, interlocutors across all three regions surveyed in this article spoke about the need for greater space, protections, and support for civil society actors working on environmental protection and climate adaptation. Many acknowledged that, despite the groundswell of enthusiasm, such activism is still in its infancy. They suggested the need for greater education and acculturation of Libya’s youth on climate change, starting in schools. These efforts are encouragingly underway by UNICEF in eastern Libya, but they need more buy-in from Libya’s authorities.31 More pressingly, though, Libyan authorities in the west and the east need to grant greater freedoms for independent civil society groups to operate freely and with foreign support, ending the restrictive laws that prevent them from doing so.

Relatedly, the dominance of Libya’s predatory armed groups over nearly every aspect of its political and economic life needs to transition to a law-based, accountable security sector—a Herculean problem that will not be solved anytime soon. Still, the urgency of tackling Libya’s climate adaptation and environmental devastation adds one more compelling reason for doing so. In all three of the regions surveyed, interlocutors were unanimous in pointing to the militias as the primary culprits for the weakening of climate resilience, through predation on the environment and, indirectly, through the perpetuation of violent conflict and the resulting population displacements, disruptions to services, and damage to infrastructure and the economy.

Lastly, while the Jabal Nafusa, Fezzan, and the Jabal Akhdar share certain commonalities in their climate vulnerabilities, they are also distinctive subregions with their own communal and ethnolinguistic identities, histories, economic resources, and other factors that militate against the one-size-fits all approach encouraged by foreign states and organizations. Addressing climate fragility in each of these areas therefore necessitates a multifaceted approach that recognizes and harnesses these local specificities, integrating on-the-ground knowledge, community-driven initiatives, and partnerships with civil society organizations. Ultimately, though, these bottom-up actions need to be accompanied by top-level will and resolve by Libyan elites, who must set aside self-aggrandizement and the pursuit of spoils to address the looming climate crisis.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the numerous Libyan interlocutors who shared their views. He would also like to thank Muadh Krayem, Muadh Sharif, and Andrew Bonney for their research assistance and Matthew Brubacher and Manal Shehabi for their comments on a draft of this article.

Notes

1 Telephone interview with Jalal Al-Qadi, director of the Misrata Agriculture Research Center, based in Misrata, Libya, October 2022.

2 Interview with Libyan farmer Bashir Alafrak in Sidi Sayeh, Libya, September 2022.

3 Interview with a Libyan agricultural consultant, Tripoli, Libya, May 2022.

4 Observations and interviews with Libyan climate officials, Tripoli, Libya, May 2022 and July 2023.

5 Interviews with Libyan activists in Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

6 Interview with Libyan farmer Bashir Alafrak in Sidi Sayeh, Libya, September 2022.

7 Interview with personnel from the National Meteorological Office, Tripoli, and telephone interview with a climate activist based in eastern Libya, July 2023. “We can’t depend on the government because of the east-west rivalry, low capacity, and seven to eight government climate entities,” stated the activist, who noted the exception of the staff of the Great Man-Made River.

8 Interview with Libyan local governance expert Otman Gajiji, Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

9 Author visit to Amazigh communities in the Jabal Nafusa, Libya, July 2023.

10 Author interviews with Amazigh farmers in and around Yifren and Qala’a, Libya, July 2023.

11 Interview with a Tuareg notable, Ghat, Libya, March 2016. “After the Fateh Revolution, Qaddafi gave us agriculture, he made us go to school. The state took care of the Tuareg,” this individual noted.

12 Telephone interview with climate consultant Matthew Brubacher, based in Geneva, Switzerland, October 2022.

13 Telephone interview with climate consultant Matthew Brubacher, based in Geneva, Switzerland, October 2022.

14 Interviews with Tuareg residents of Ubari during a visit to the town, March 2016.

15 Interview with Tuareg activist and former official, Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

16 Interviews with African migrants at detention facilities in Tripoli and Zawiya, March 2016.

17 PowerPoint briefing, “Sand and Dust Storms in Libya,” provided to the author by the National Meteorological Office, Tripoli, Libya, May 2022.

18 Telephone interview with Jalal Al-Qadi, director of the Misrata Agriculture Research Center, based in Misrata, Libya, October 2022.

19 Interview with Libyan local governance expert Otman Gajiji, Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

20 Interviews with environmental and climate officials in Tripoli and Misrata, May 2022 and July 2023.

21 Interview with an eastern-based Libyan official in the National Meteorological Office, Tripoli, July 2023.

22 Telephone interview with an eastern-based Libyan climate activist, July 2023.

23 Telephone interview with an eastern-based Libyan climate activist, July 2023; and interview with officials from National Meteorological Office, Tripoli, Libya, May 2022.

24 In-person and telephone interviews with Libyan officials and activists from eastern Libya, July 2023.

25 Telephone interviews with European diplomats and Libyan activists from eastern Libya, 2022 and 2023.

26 Interview with a Libyan official from eastern Libya, location undisclosed, July 2023.

27 Telephone interview with a Libyan climate activist, name and location undisclosed, September 2023.

28 As noted by Middle East climate scholar Jeannie Sowers, “The degree to which states are tolerant of local-level initiatives and mobilization will become only more important as climate impacts intensify.” Jeannie Sowers,”The High Stakes of Climate Adaptation in the Middle East and North Africa,” Current History, December 2017, 348–354, https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2017.116.794.348.

29 Interview with a Tuareg activist and former official, Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

30 Interview with Libyan local governance expert Otman Gajii, Tripoli, Libya, July 2023.

31 Telephone interview with a Libyan climate activist based in eastern Libya, July 2023.