Key Takeaway: Niger’s junta annulled defense cooperation agreements with the United States, underscoring its prioritization of growing partnerships with like-minded authoritarian regimes such as Russia and Iran over maintaining cooperation with the United States. Russian mercenaries will likely backfill US positions if US forces withdraw from Niger, which would increase the conventional military and irregular migration threats Russia poses to NATO’s southern flank and consolidate Russian logistics in Africa. Decreased US influence in Niger will also create opportunities for expanded Russian and Iranian cooperation with Niger by degrading America’s ability to dissuade or incentivize Niger from cooperating with these alternative partners. The end of American-Nigerien defense cooperation will also harm both countries’ counterterrorism goals.

Assessment:

Niger’s junta annulled its defense agreements with the United States days after tense meetings with a high-level US delegation. US Assistant Secretary of State Molly Phee and US Africa Command Commander Gen. Michael Langley led a US delegation that met with top Nigerien officials on March 12 and 13.[1] Nigerien junta head Gen. Abdourahamane Tiani refused to meet with the American delegation despite the delegation extending its stay through March 14.[2] US officials expressed concerns about the junta’s growing ties with Iran and Russia during meetings that US officials described as “direct and frank.”[3]

The junta annulled military cooperation agreements with the United States on March 16.[4] The spokesperson labeled the deals as lopsided and accused the United States of failing to adequately share intelligence gathered using its drone fleet and forcing Niger to pay billions of dollars to maintain donated American aircraft.[5] The spokesperson also scolded the US delegation’s “condescending attitude” and threats during the March 12–13 meetings.[6] US defense and diplomatic officials reacted to the announcement by saying that communication channels with the junta remained open and that the United States is seeking clarification and alternative paths forward to continue the partnership.[7]

The junta’s decision puts the future of the remaining active US drone base and 700 US military personnel in Agadez, northern Niger, in question.[8] The United States uses the base to monitor and support security forces operating against al Qaeda and Islamic State–affiliated militants in northwest Africa, including the Lake Chad Basin, Libya, and the Sahel.[9]

Niger is unlikely to compromise on its efforts to grow ties with Iran and Russia to maintain its partnership with the United States. The United States has tried to take a more pragmatic and nonconfrontational approach to the junta after the junta took power in July 2023. The United States initially broke from its French partners in its approach to the coup. France supported a more aggressive approach, including supporting a regional military intervention to restore democratic rule, while the United States dispatched an envoy to engage the junta.[10] The United States waited over two months to formally declare the unconstitutional government change a coup.[11] The United States also recognized the junta’s legitimacy but called for a short transition in the last quarter of 2024. The US ambassador to Niger presented her credentials to the junta in December.[12] Niger’s decision to maintain ties with the United States while growing ties with Iran and Russia up to March 16 indicates that it was trying to balance these partnerships under these conditions.

The United States has taken a tougher stance toward Niger since January 2024, given Niger’s growing ties with Iran and Russia, contributing to the current impasse. The France-based, Africa-focused investigative outlet Jeune Afrique reported on March 19 that sources close to the Nigerien junta and Western diplomats said the United States opposed Niger sliding toward Iran and Russia and the potential of a Russian mercenary deployment to Niger.[13] The Wall Street Journal reported on March 17 that US officials accused Niger of secretly exploring a deal to allow Iran access to its uranium reserves during the March 12–13 meetings.[14] Jeune Afrique also reported that US suspicions that one of the already-signed Iran-Niger energy agreements involved uranium provision became a redline for future US cooperation with Niger.[15] The junta explicitly rejected this hardened stance and cited it as a cause for annulling the US defense deals in its statement that denied the US delegation’s “false accusation” of a secret uranium agreement with Iran and lambasted the US delegation’s “threats.”[16]

The Nigerien junta has signaled from its inception that it wanted to grow cooperation with like-minded authoritarian regimes, such as Russia and Iran, even at the expense of effective partnerships with Western states. The Nigerien junta has staked its popular legitimacy and internal military support on maximizing national sovereignty, cutting ties with its former colonizer and US partner France and diversifying partnerships with authoritarian countries, such as Russia and Iran.[17] These alternative partners are better suited to help the junta boost regime security and enable a more aggressive and militarized counterterrorism strategy. The junta quickly forced French troops out of the country and grew ties with Russia throughout 2023.[18] The junta has been interested in deploying Russian mercenaries since it gained power in July and continued pursuing closer military cooperation with Russia.[19] The junta also signed agreements on energy, health, and finance with Iran in January 2024.[20]

The deterioration and rupture of France’s relationship with Mali from 2020 to 2022 foreshadowed the likely trajectory of the Niger-US partnership. The Malian junta—like the Burkinabe and Nigerien juntas since—pursued a closer relationship with Russia because it offers a more attractive partnership that addresses their broader needs for authoritarian regime security while aligning with their anti-Western and aggressively militarized counterinsurgency outlooks.[21] France also initially took a conciliatory stance toward the Malian junta, but ties eventually ruptured as Malian officials adopted anti-French stances, consolidated power with a second coup, and uncompromisingly sought to grow relations with Russia.[22] The Malian junta continued to pursue this new relationship beyond France’s “redline” of deploying Wagner Group mercenaries in 2021.[23] The move ended the strained relationship and showed that the Malian junta was willing to risk its decade-long military partnership with France to pursue an unrestrained new partnership with Russia.[24]

Russian mercenaries could backfill abandoned US positions in northern Niger within months of US forces leaving the country, which would pose various threats to NATO’s southern flank and consolidate Russian logistics networks in Africa. CTP continues to assess that Niger will likely contract Russian mercenaries to help fill the capacity gaps left by the departure of French and potentially US forces and address the deteriorating security situation in the country.[25] The Nigerien junta initially showed interest in a Wagner Group deployment in its first days in power, although this was when it faced a potential regional invasion to restore democratic rule.[26] The junta has since continued meeting with Russian defense officials linked to Russian mercenary activity and signing additional defense agreements.[27]

Russia has also demonstrated its interest in expanding its military footprint in the Sahel. There are already 1,000–2,000 Kremlin-funded Wagner Group mercenaries that have been in neighboring Mali since 2021.[28] Numerous open-source intelligence organizations have also assessed that the Russian Ministry of Defense began ramping up recruitment in the fourth quarter of 2023 for its new private military company, called “Africa Corps.” Russia’s Africa Corps aims to establish footholds in Burkina Faso and Niger and subsume preexisting Wagner operations in other countries such as Libya and Mali.[29] At least 100 Russian Africa Corps mercenaries deployed to Burkina Faso in January 2024.[30] Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger are part of an alliance, which creates further opportunities for multilateral cooperation between the juntas and Russia.[31]

Russian mercenaries would likely backfill the inactive US bases in Niamey and the northern Nigerien city Agadez as they did French positions in Mali. Wagner Group mercenaries quickly began operating out of former French bases in Mali immediately after French forces withdrew in 2022.[32] Wagner Group and Malian army forces also assumed control over several vacated UN bases in northern Mali as UN forces withdrew throughout 2023.[33]

Russia would be unlikely to base drones with its mercenaries in Niger in immediate term. However, presence of Russian mercenary bases in northern Niger would create an opportunity for the Kremlin to deploy drones in the area to threaten NATO’s southern flank in the future. Russian mercenaries in Mali have not deployed or indicated they plan to deploy Russian drones in Africa. Wagner auxiliaries in Mali have relied on Malian forces’ use of Turkish TB2 drones.[34] Niger also has its own TB2 drones.[35] Russia has supported its Wagner mercenaries in Libya with conventional Russian aircraft but no drones.[36] The rapid increase in Iranian and Russian production of Shahed-style drones for Russia’s war in Ukraine increases the risk that the Kremlin leverages some of this production capacity to equip mercenaries in Africa with drones in the future.[37]

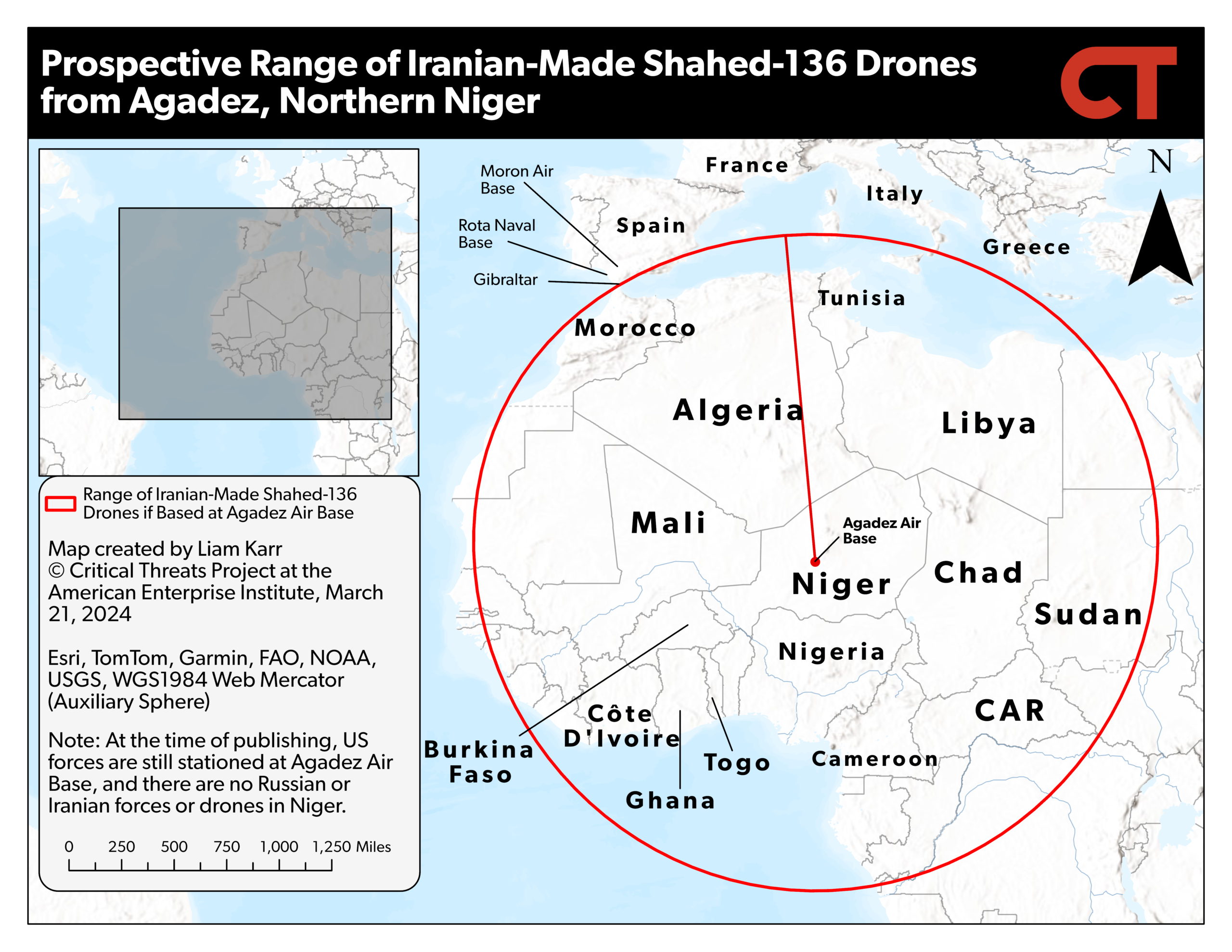

Shahed 136 drones based near Agadez would be within range of key US and NATO installations and parts of the Mediterranean Sea. The Shahed 136, also known as Geranium s in Russia, has a maximum range of 1,553 miles (2,500 kilometers).[38] Agadez is 1,523 miles from Sicily and the southern tip of the Italian mainland, 1,555 miles from Gibraltar, and roughly 1,600 miles from the US-Spanish air and naval bases in southern Spain.

Figure 1. Prospective Range of Iranian-Made Shahed 136 Drones from Agadez, Northern Niger

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian forces or drones in Niger.

Source: Liam Karr.

The Kremlin has not armed its mercenaries in Africa with drones, including in places closer to Europe, such as Libya or Mali. Russian doctrine indicates that the Kremlin is likely interested in such opportunities in the event of a conflict with NATO, however. Russian strategy and doctrine emphasize the importance of quickly attacking “critically important ground-based facilities” on short notice to destroy an enemy’s military and economic potential.[39] This illustrates the Kremlin’s likely intent in securing such drone placements in the future to prepare for a conflict with NATO. Locations like Libya and Mali are more comfortably within range of the Mediterranean and Europe; this would make Libya and Mali more likely base locations should the Kremlin decide to base drones in Africa in the future.

Russia would also likely use positions in northern Niger to exploit trans-Saharan migrant-smuggling routes to increase irregular migration flows to Europe and enrich its mercenaries. Russia has repeatedly and systematically weaponized migrant crises in Europe. The Russian and Belarussian governments have flooded the borders of Finland, Lithuania, and Poland with refugees since 2021.[40] Their tactics included luring refugees from the Middle East and Africa on flights to Europe based on false promises before dropping them at the border.[41] Russia’s attacks on agricultural facilities in Ukraine and scrapping of the Black Sea grain deal in July 2023 indirectly targets food availability in Africa, creating another cause for mass migration.[42] The Kremlin also foments prolonged instability in theaters where it is active, such as Syria, Ukraine, and now the Sahel, which creates long-term refugee crises.[43]

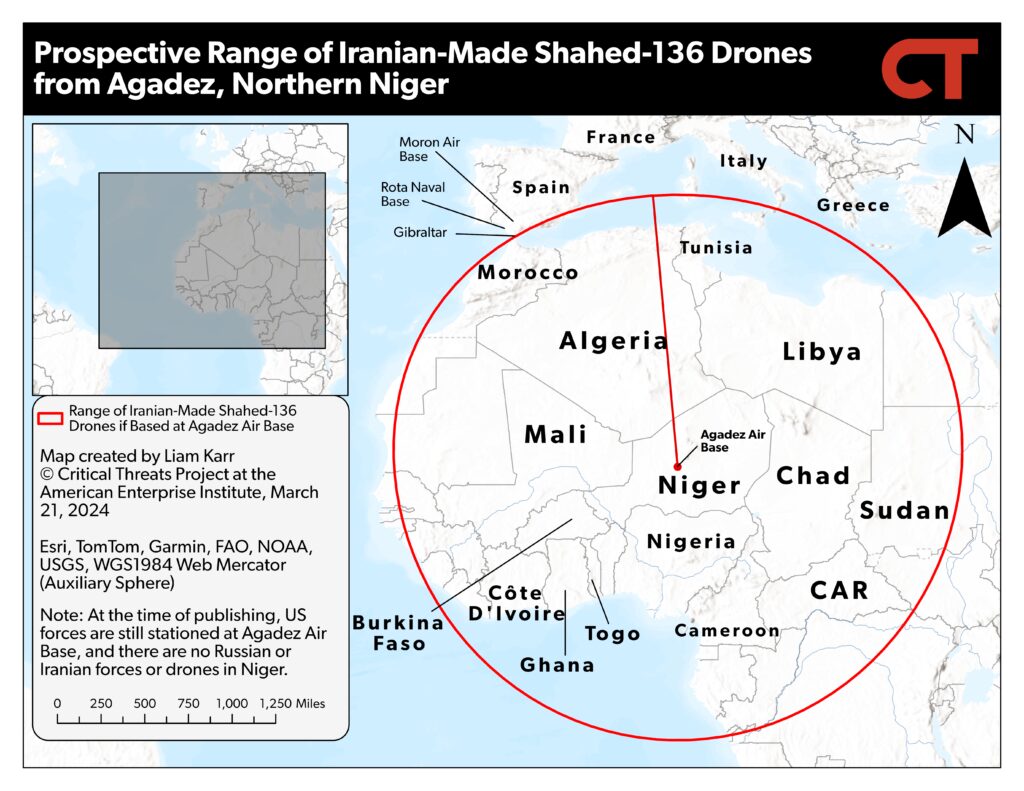

Russia is now active along many of the trans-Saharan migrant routes, increasing its opportunities to facilitate mass migration. Russian mercenaries in the Sahel have contributed to a massive spike in human rights abuses since 2021, helping fuel record-high levels of trans-Saharan migration to Europe.[44] Russian security assistance has simultaneously failed to slow the Salafi-jihadi insurgency, creating conditions for worsening instability that continues to prompt migration.[45] Russia’s partners in the Nigerien junta also annulled an EU-backed migration law that aimed to stem these flows in December 2023, benefiting both parties but directly increasing migrant flows to North Africa and Europe.[46] Russia’s growing footprint in sub-Saharan Africa also increases opportunities for Russian personnel to directly lure more migrants to Europe to drop at NATO’s borders.

Russian mercenaries in Niger can insert themselves into the local migrant-smuggling economy to further increase profits and migrant flows. Facilitating migration to North Africa is a major local economy in northern Niger, and Agadez is a primary staging point.[47] Thousands of people gather in convoys to travel across the desert to Libya, where they seek to reach the Mediterranean coast and take a boat to mainland Europe.[48] Nigerien security forces are already involved in the migrant-smuggling economy by charging migrant smugglers at security checkpoints and escorting migrant convoys.[49] Russian mercenaries have shown adept at inserting themselves in other informal African economies by cultivating ties with civilian and military power brokers and would do the same in Niger.[50] This would allow them to both profit off migration and directly facilitate migration by helping convoys reach the Mediterranean.

The EU border patrol agency and numerous European officials have warned in 2024 that Russian President Vladimir Putin is attempting to foment greater refugee flows from Africa to destabilize Europe, influence elections, and undermine support for Ukraine.[51] The EU has repeatedly identified migration as a critical issue after the 2010s Syrian refugee crisis destabilized the continent by overwhelming the EU asylum system and amplifying racial tensions, giving rise to ethno-nationalist right-wing political movements.[52] Putin has repeatedly generated refugee crises to exploit this weakness by prolonging military conflicts and humanitarian emergencies that increase migration flows and then either decreasing local migration enforcement measures or directly supporting migrants and smugglers.[53] The EU border patrol agency noted that 380,000 migrants attempted to cross into Europe from Libya in 2023, the highest number of irregular crossings since 2016.[54]

Figure 2. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Clingendael Institute; Norwegian Center for Global Analyses.

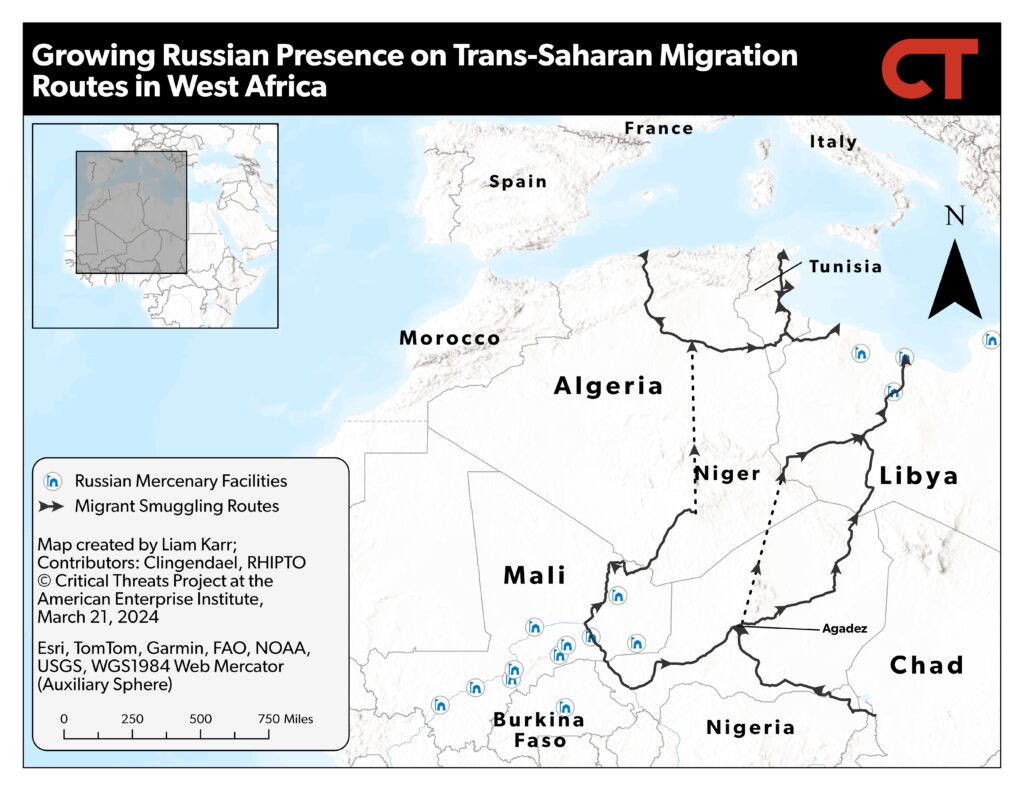

Russian basing in northern Niger would also strengthen Russia’s logistical network in Africa. Russian basing in Agadez would help bridge the gap in the Russian Ministry of Defense’s air-supply network between positions in Libya and sub-Saharan Africa.[55] Agadez is 1,100 miles or less from the Wagner-controlled airbases in Libya and just over 1,100 miles from major Russian bases in Bamako to the west and Bangui—the capital of the Central African Republic—to the southeast.[56]

Figure 3. Russian Mercenary Facilities in Northwest Africa

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian forces or drones in Niger.

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

A US withdrawal from Niger would undermine America’s counterterrorism posture in West and North Africa despite potential fallback options, which could increase the transnational threat risk to Europe and the United States. US Africa Command head Gen. Langley warned that the loss of US basing in the Sahel will “degrade our ability to do active watching and warning, including for homeland defense.”[57]

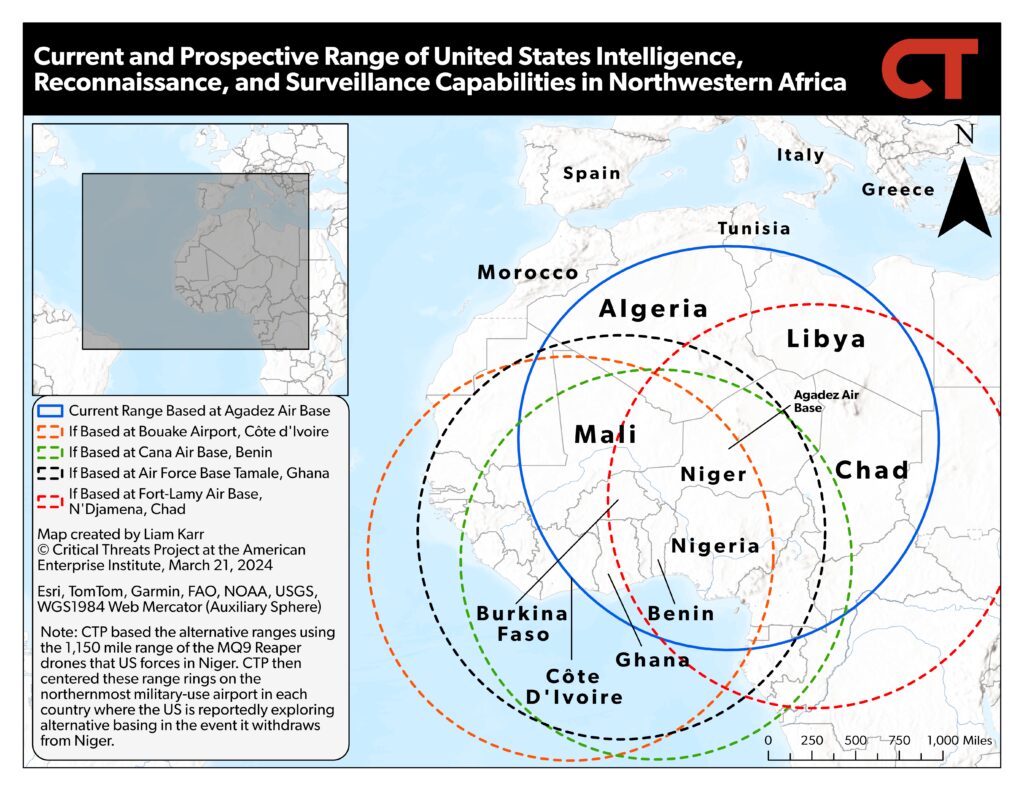

The United States is exploring alternative basing options in the Gulf of Guinea and Chad. The Wall Street Journal reported on January 3 that the United States held preliminary talks for US reconnaissance drones to use airfields in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Benin.[58] French newspaper Le Monde reported in January that the US was considering joint bases with France on the continent.[59] The most likely destination for such a base would be Chad, where French forces relocated after departing Niger at the end of 2023.[60]

These alternative options have practical drawbacks, however. The relocation of US reconnaissance drones at least 500 miles south, to the Gulf of Guinea, would significantly restrain US reconnaissance in North Africa and potentially the Lake Chad Basin. American forces at the Agadez Air Base use MQ9 reaper drones, which have a range of 1,150 miles.[61] Relocation into any of the three countries will remove Africa-based surveillance of Islamic State cells in Libya and most of Algeria. Relocation to the farthest West option—Côte d’Ivoire—would also eliminate eyes on the Lake Chad Basin, where the Islamic State’s West Africa Province and regional administrative node is based. Relocation to Chad would eliminate coverage of the western halves of Burkina Faso and Mali, where al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate is firmly entrenched.

Figure 4. Current and Prospective Range of United States Intelligence, Reconnaissance, and Surveillance Capabilities in Northwestern Africa

Note: CTP based the alternative ranges using the 1,150-mile range of the MQ9 Reaper drones that US forces use in Niger. CTP then centered these range rings on the northernmost military-use airport in each country where the US is reportedly exploring alternative basing, in the event it withdraws from Niger.

Source: Liam Karr; https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/22/us/politics/drone-base-niger.html; https://www.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104470/mq-9-reaper.

The political situation in Chad also makes it a potentially unstable partner for US forces.[62] Chad is currently ruled by a more pro-Western junta, but there is still anti-French sentiment that threatens France’s long-term presence in the country.[63] The Sahelian juntas and Russia have all played on heightened anti-French sentiment to advance their aims.[64] The Chadian junta head also visited Moscow on January 24, potentially indicating a shift in Russia’s long-running efforts to increase its influence in Chad after supporting Chadian rebels in 2019.[65] The January meeting and potential reset of relations increases the risk that the Chadian junta follows the lead of the other Sahelian states and realigns closer to Putin’s authoritarian regime.[66] The United States increasing cooperation with the Chadian junta, despite the Chadian military killing a prominent opposition leader and government critic on February 29, also delegitimizes Western arguments about the importance of democratic governance that the West has leveled at the other Sahelian juntas.[67]

Niger breaking ties with the United States will also further degrade America’s ability to dissuade or incentivize Niger from cooperating with Iran, including on uranium provision. Niger’s growing ties with Iran and a potential uranium exploration deal were major US concerns heading into the March 12–13 visit.[68] CTP previously assessed that it is unlikely Iran attempts to obtain Nigerien uranium due to Iran’s domestic capabilities and a lack of indicators that the junta was looking to replace the Western-based mining companies that currently own the majority shares in nearly all Nigerien uranium mines.[69] Ending defense cooperation removes a key avenue of collaboration between the US and Niger that the US had as leverage to incentivize a democratic transition and more restrained relations with Iran and Russia. US law further limits the US government’s leverage by restring the government from providing any foreign assistance to coup governments outside of humanitarian aid and democratic promotion.[70]

Niger replacing the United States with Russia as its primary security partner will degrade the Nigerien military’s effectiveness and strengthen Islamic State and al Qaeda–affiliated insurgents. Niger will lose crucial US-backed equipment, training, and support programs. The United States has provided three C-130H Hercules transport aircraft, two Cessna-208 Caravan light transport aircraft, and at least 50 Mamba 7 armored personnel carriers to the Nigerien military since 2012, making it the leading provider for the Nigerien military over this period.[71] The end of US maintenance, spare-part provision, and training programs will slowly degrade the usability of more sophisticated systems like the transport aircraft.[72] These aircraft enable the military to quickly move troops, vehicles, and supplies to insurgent-afflicted areas.[73]

US forces in Niger have also trained Nigerien forces; provided intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) in support of Nigerien operations; and advised and assisted Nigerien troops on more rare occasions.[74] The decrease in ISR since France’s withdrawal from Mali and a decrease in cooperation with other counterterrorism partners providing ISR have already significantly improved Salafi-jihadi militants’ freedom of movement in the Sahel.[75] The lack of ISR enables militants to gather in larger numbers and attack security forces with less warning, increasing the scale and severity of their attacks. Such large-scale and high casualty attacks have been on the rise in Niger since the US suspended ISR support for Nigerien forces after declaring the junta a coup government in October 2023.[76] At least 100 Islamic State militants ambushed Nigerien forces in northwestern Niger on March 21, killing at least 20 soldiers, for example.[77]

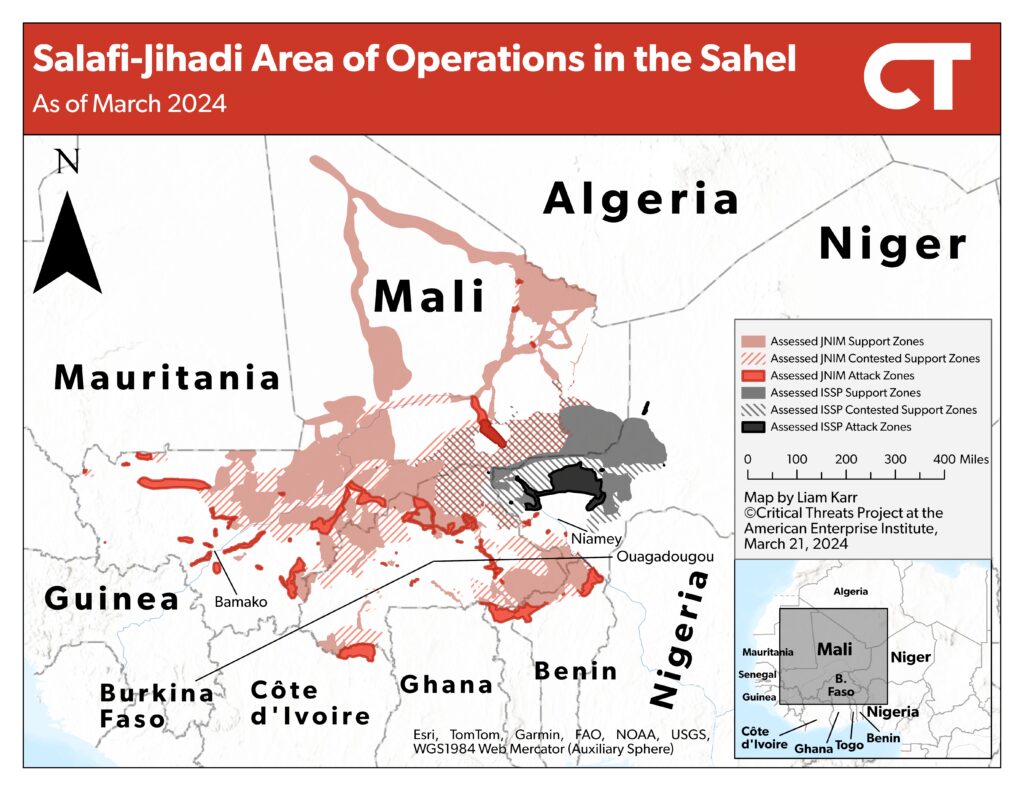

Russian mercenaries in Africa have been ineffective—if not counterproductive—in counterinsurgency operations. Wagner Group forces failed to slow the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Mozambique in 2019 and have failed to degrade the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in the Sahel.[78] Wagner’s brutal tactics are also counterproductive, as they exacerbate human rights abuses against civilians that insurgent groups use to gain popular support.[79] Al Qaeda– and Islamic State–linked groups are taking advantage of these shortcomings to strengthen their support zones and expand toward political centers in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.[80]

Figure 5. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Sahel

Note: JNIM stands for al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen; ISSP stands for the Islamic State’s Sahel Province.

Source: Liam Karr.