Key Takeaways:

- Togo. Reports of a small and potentially growing number of Russian military advisers in Togo indicate that Russia and Togo are increasing their ties as the Kremlin aims to expand its influence beyond the Sahel in West Africa. The Kremlin likely seeks to use Togo as a logistical node to support its other operations in Africa. Russia may also have a long-term aim of securing an Atlantic Ocean port in Togo, which would support the Kremlin’s strategic efforts to increase its threat to NATO’s flanks through basing in Africa. Russia will have to offset competing partnerships with Togo’s remaining non-French Western partners, such as the United States, but a future increase in instability could lead the Togolese government to further increase ties with Russia.

- Burkina Faso. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate is increasing violence against civilians in eastern Burkina Faso, likely to coerce and deter civilians from resisting the group to expand its support zones. The group’s campaign is likely setting conditions to besiege the Est regional capital, Fada N’Gourma, the largest town in southeastern Burkina Faso.

Assessments:

Togo.

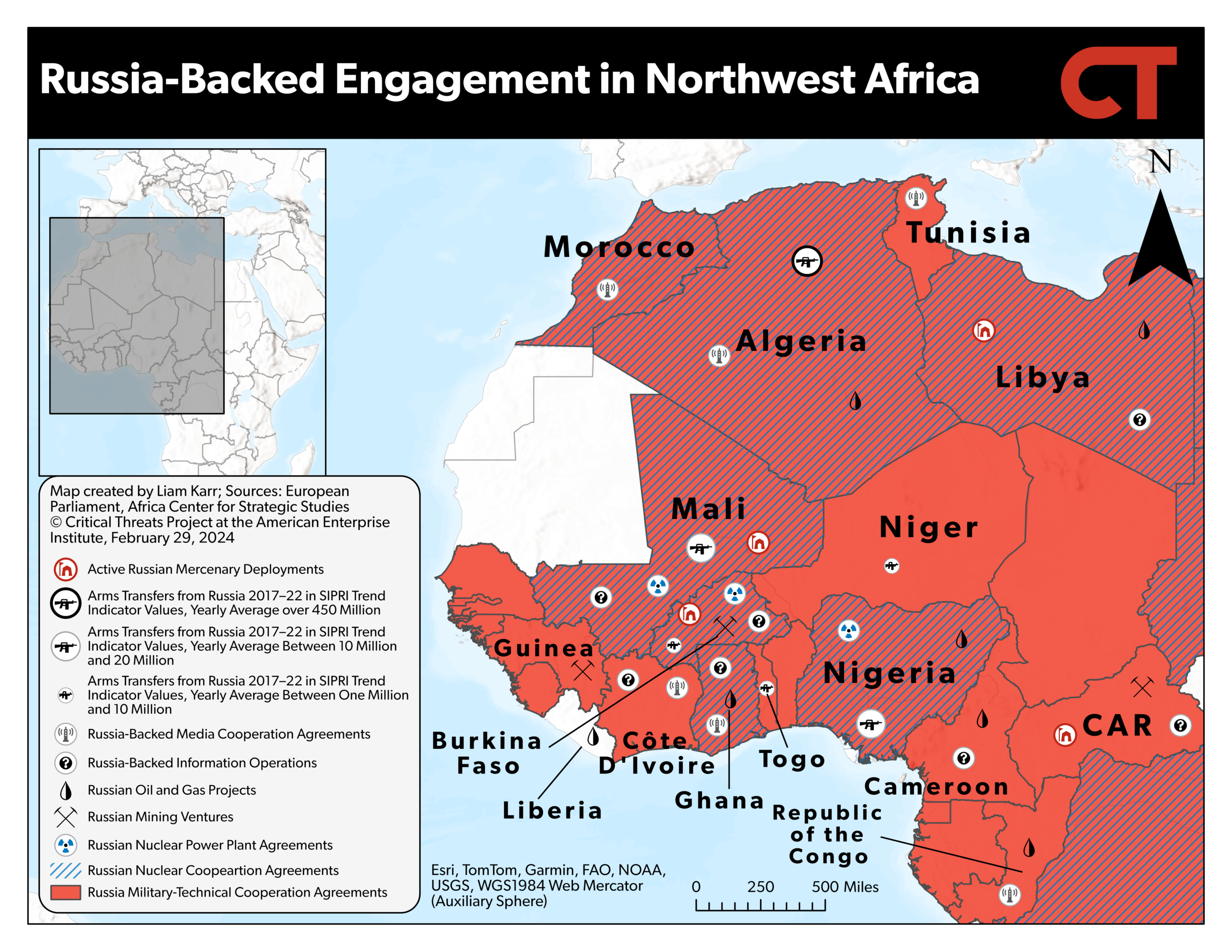

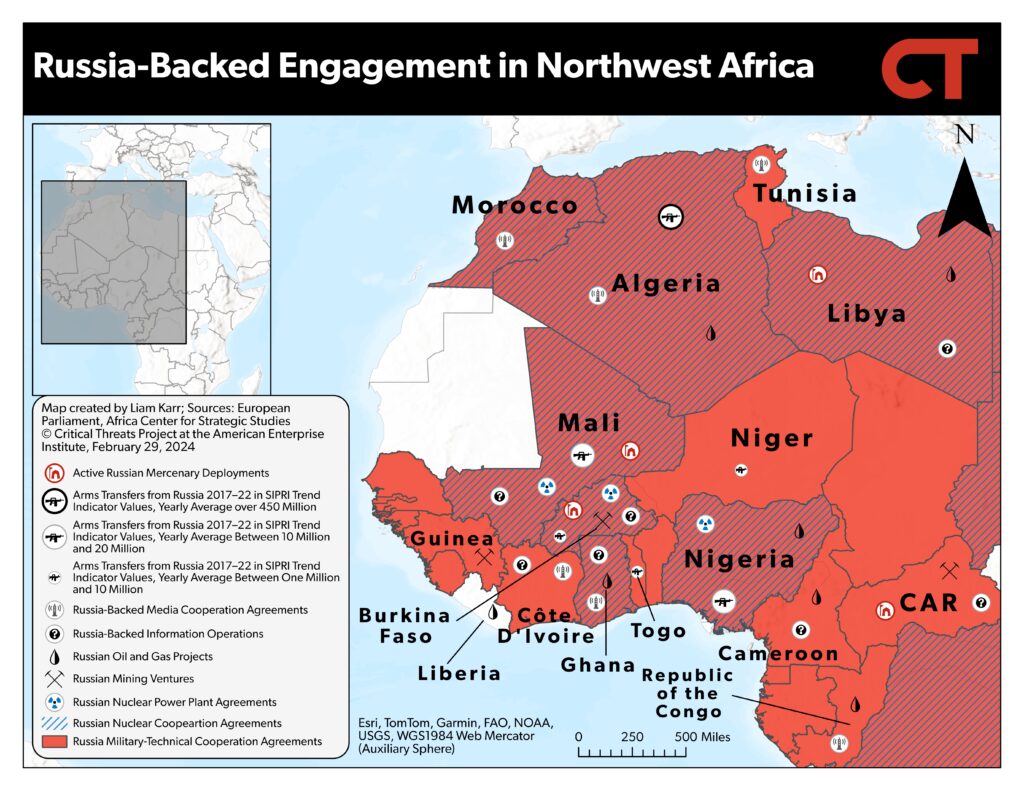

Russia and Togo are increasing ties as the Kremlin aims to expand its influence beyond the Sahel in West Africa. French-based investigative news site Africa Intelligence reported on February 19 that a contingent of 30 Russian military advisers that recently arrived in Togo are helping Togolese troops build a new military camp on the border with Burkina Faso.[1] The purpose of the camp is to defend against Salafi-jihadi attacks that largely emanate from Burkina Faso.

The presence of Russian military advisers marks an expansion in Russian-Togolese military cooperation that has been growing since 2022. Russia delivered three Mi-35 combat helicopters and two Mi-17 transport helicopters to Togo in late 2022.[2] This deal established Russia over France and the United States as the leading provider of military hardware in Togo from 2012 to 2022, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s trend-indicator value index.[3] It also made Togo the leading recipient of Russian military hardware among the Francophile West African littoral states over the same period.[4] The trend-indicator value measures the volume of military capability transfers rather than the financial value of arms transfers.[5]

The Kremlin likely seeks to use Togo as a logistical node to support its other operations in Africa. The National Resistance Center of Ukraine, which is a Ukrainian Special Forces–run information operation and partisan support organization, claimed on February 24 that the Russian armed forces are planning to deploy a newly formed “African Expeditionary Force” to Togo in March 2024.[6] The expeditionary force would support the incumbent president in the upcoming 2025 elections.[7] The National Resistance Center also said that this would be the first step in a larger effort to secure Russian naval basing in Togo.[8] The naval base would strengthen a logistics corridor connecting Russian mercenary bases from Libya, through Burkina Faso and Mali, to the Gulf of Guinea via Togo.[9]

This rumored plan is like other types of Russian engagement in Africa that the Kremlin has described as a “regime survival package.”[10] The Royal United Services Institute, a London-based think tank, released a report in February 2024 based on internal Russian documents that confirmed that the Kremlin is explicitly pursuing a colonial strategy based on elite capture in Africa.[11] The Kremlin leverages formal state power and unconventional military units—such as the Wagner Group and Russian intelligence—to offer local elites military support, allyship in international bodies, and information campaigns to boost the elites’ domestic support.[12] Russia increases its influence over target governments and isolates them from the West as a result.[13]

The Wagner Group’s network in central Africa offers a blueprint for a similar regional logistics network. In Cameroon, a handful of Wagner Group operatives have leveraged the Kremlin’s good relations with the country’s longtime dictator to gain access to Cameroonian ports.[14] Wagner uses the ports to import and export goods and equipment related to its primary theater of operations in the neighboring Central African Republic.[15] Togo—like Cameroon—is not as reliant on rents as the states where the Kremlin has agreed to deploy mercenaries to gain access to African rents and resources.[16] Togo also does not require the same degree of security assistance as Burkina Faso and Mali, which are at the epicenter of the Sahel’s Salafi-jihadi insurgency. Both countries have deployed Russian mercenaries to combat the insurgency.[17]

Figure 1. Russian-Backed Engagement in Northwest Africa

Source: Liam Karr; European Parliament; Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Note: “SIPRI” is Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The Kremlin may also have a long-term goal of securing an Atlantic Ocean port in Togo to support its strategic aims of expanding another flank from which to threaten NATO with naval basing in Africa. The Ukrainian Resistance Center’s assessment said that Russia aimed to secure naval basing in Togo as part of a logistics corridor.[18] However, the Kremlin has also sought to expand its military naval basing in other parts of Africa in recent years. These efforts aim to expand its military footprint and offset Turkey’s closing of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which prevents Russia’s Black Sea Fleet from supporting Russian activity in the Mediterranean and Syria.[19] Russia has repeatedly backed factions in Sudan that it believes will follow through on a 2017 agreement for a Red Sea port in Sudan and is trying to secure a Mediterranean port in Libya, which would complement its port at Tartus, Syria.[20]

Russian ports in Africa would pose a long-term strategic threat to NATO by supporting Russia’s aim to have a standing force able to threaten NATO critical infrastructure with long-range cruise missile strikes from the sea.[21] Russian strategy and doctrine emphasize the importance of preemptive deployments of naval forces to establish deterrence and set favorable conditions for an ensuing conflict.[22] It identifies the navy as a critical tool to conventionally “attack critically important ground-based facilities” from the sea on short notice to destroy an enemy’s military and economic potential.[23]

Russian naval activity in the Mediterranean poses a clear danger to Europe. An Italian MP and former head of the Italian armed forces claimed in January 2024 that the Kremlin would base nuclear-powered submarines in Libya if it secured a base.[24] A Russian naval base at Tobruk would put most of central and southern Europe within range of Russian frigates and submarines with Kalibr cruise missile systems.[25]

Russian basing in the Gulf of Guinea would create an alternative but more limited flank to the Mediterranean and bring Russian naval platforms closer to the United States. Russian nuclear-powered submarines in the Atlantic would be past the main NATO checkpoint to the Atlantic at the British territory of Gibraltar, increasing the risk to the United States.[26] Nuclear-powered submarines with Kalibr systems would also be in range to strike Gibraltar once they reached the Mauritanian coast, just under 1,400 miles from the Togolese port capital, Lome. Russia deployed an Admiral Gorshkov–class frigate—which has a seaworthy range of 5,580 miles—to conduct a computer simulation hypersonic cruise missile strike exercise in the Atlantic Ocean in January 2023, underscoring its intention to project naval power into the Atlantic.[27]

Russia will have to manage competition with Togo’s remaining non-French Western partners, such as the United States, to secure its aims. Togo has tried to balance ties with non-French Western partners as it expands its partnership with Russia instead of using Russian aid to outright replace Western assistance.[28] Togo is one of five coastal West African countries that receive support from the US Global Fragility Act (GFA), which supports long-term, locally-led plans to increase community resilience and address the root political causes of instability.[29]

The program is a whole-of-government plan involving the US Defense and State Departments and the US Agency for International Development that provides locally attuned development, political, and security assistance.[30] US Africa Command Commander Gen. Michael Langley and the US ambassador to Togo led a delegation meeting with the Togolese president, military chief of staff, and other leaders in August as part of these efforts.[31]

A future increase in instability could lead the Togolese government to increase ties with Russia. A deterioration of the security situation in northern Togo would jeopardize the continued backing of Western partnerships and lead to more militarized policies, which favor cooperation with Russia. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate uses Togo as a buffer zone and transit route for activities in Benin and Burkina Faso, which has limited it to a low-level, cross-border threat in Togo.[32] However, the group has shifted to establishing a more active and locally driven insurgency in neighboring Benin since 2021, which highlights the risk of a similar move in Togo in the future.[33] The military governments leading Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger responded to deteriorating security by overthrowing their civilian-led governments, rejecting Western-backed counterterrorism assistance, and taking an even more aggressive and militarized approach with Russian backing.[34]

Internal political pressure could also drive Togo’s president into the Kremlin’s orbit. Togolese President Faure Gnassingbe’s authoritarian tendencies increase his alignment with Russia. Gnassingbe will be seeking his fifth—and legally final—term in upcoming elections scheduled for 2025.[35] He has been in office since the military installed him to succeed his father in 2005.[36] Opposition figures claimed widespread election fraud during the most recent elections in 2020, adding to Gnassingbe’s questionable democratic credentials.[37] Togolese authorities have also suppressed independent information and press freedoms in jihadist-afflicted areas of northern Togo by harassing journalists since 2022.[38] Russia has helped authoritarian leaders subvert democracy across Africa, and the Ukrainian Resistance Center’s claim that Russia is planning to send operatives to support Gnassingbe’s reelection bid matches the other kinds of support Russia has offered on the continent.[39]

Russia has shown that it ideologically and materially outcompetes the West in unstable authoritarian-led countries in Africa. Russia’s military doctrine is more aligned with a heavily militarized and callous counterinsurgency approach.[40] The GFA exemplifies this divergence in Russian and Western outlook, as the program says it aims to “incorporate lessons learned from overly securitized approaches” (emphasis added) in the Sahel over the past decade.[41]

This discrepancy has the practical effect of making Russian military hardware easier to acquire for countries facing democratic or humanitarian concerns from the West.[42] Russia has also repeatedly shown that it will back friendly authoritarian leaders through “regime security packages” that keep Kremlin allies in power by mitigating domestic and international backlash.[43] These kinds of Russian partnerships accelerate breakdowns between the African states and Western partners by worsening democratic and human rights records.[44] This distancing from the West further increases partner countries’ reliance on Russia and brings them into the Kremlin’s orbit.[45]

Burkina Faso.

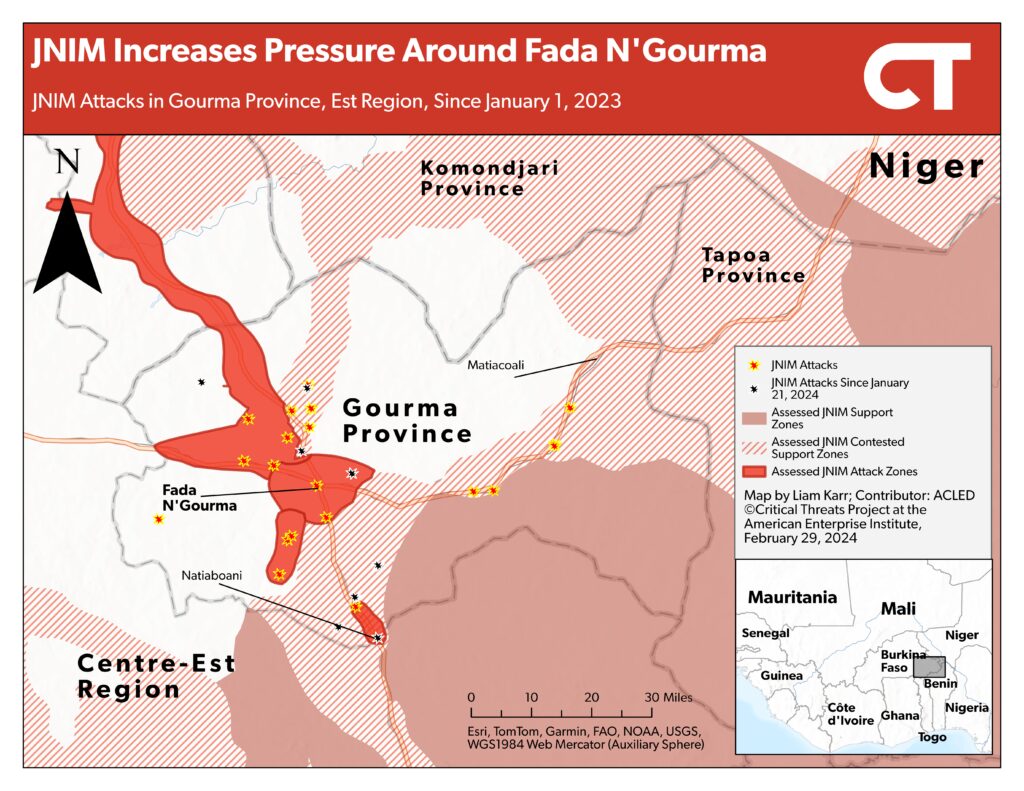

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate is increasing violence against civilians in eastern Burkina Faso, likely to coerce and deter civilians from cooperating with security forces or arming themselves. Militants from Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) massacred “dozens” of civilians attending morning prayer at a mosque in Gourma province and simultaneously attacked a military base in the same town on the morning of February 25.[46] JNIM has carried out at least eight attacks in southeastern Burkina Faso’s Gourma province since January 21.[47] This matches the group’s previous peak rates over the past year in July and November 2023.[48]

The attacks since January 2024 have significantly grown in severity, especially for civilians. JNIM killed 10 or more people in four attacks in Gourma province in 2023, only one of which targeted civilians or civilian militias.[49] However, six of the attacks since January 21 have killed 10 or more people, including an attack that killed 50 civilians on February 7.[50] Five of the six attacks have involved casualties among civilians or civilian militias.[51]

JNIM’s civilian targeting campaign is benefiting from a lack of effective state forces in the region. The disproportionate targeting of civilians underscores the lack of formal security forces in the area that can either defend villages or reinforce civilian militias. A special police unit retreated to the regional capital in one instance, underscoring the inadequacy of state security forces even when they are present.[52] The Burkinabe military announced on February 23 that it had deployed special force units to the Est region, which could help stabilize the situation.[53]

JNIM is likely setting conditions to besiege the regional capital, Fada N’Gourma. All of JNIM’s attacks in the region since January 2024 have occurred along roads that lead to Fada N’Gourma or in rural areas within 25 miles of the regional capital. This campaign has forced dozens of civilians to flee from their villages to Fada N’Gourma.[54] People who remain in their villages risk being the target of JNIM violence, especially if they attempt to resist the group. The end effect is that JNIM secures freedom of movement across these areas.

Figure 2. JNIM Increases Pressure Around Fada N’Gourma