Key Takeaways:

- Mali. The Wagner Group established control over its first gold mine in Mali and will likely attempt to expand its influence over northern Mali’s artisanal mines to bolster the Kremlin’s sanctions evasion efforts. The Kremlin has used this playbook to accrue billions from artisanal mines in Sudan, contributing to the $2.5 billion in gold the Kremlin has generated in Africa since it invaded Ukraine in 2022.

- Somalia. Al Qaeda’s Somali affiliate al Shabaab has conducted several attacks in Mogadishu since December 2023 that are part of efforts to counter government initiatives to degrade the group’s influence in the capital. Some of the attacks support al Shabaab’s substantial revenue collection operations, which help it finance military purchases and support al Qaeda’s global goals, including attacking the United States and its interests.

Assessments:

Mali.

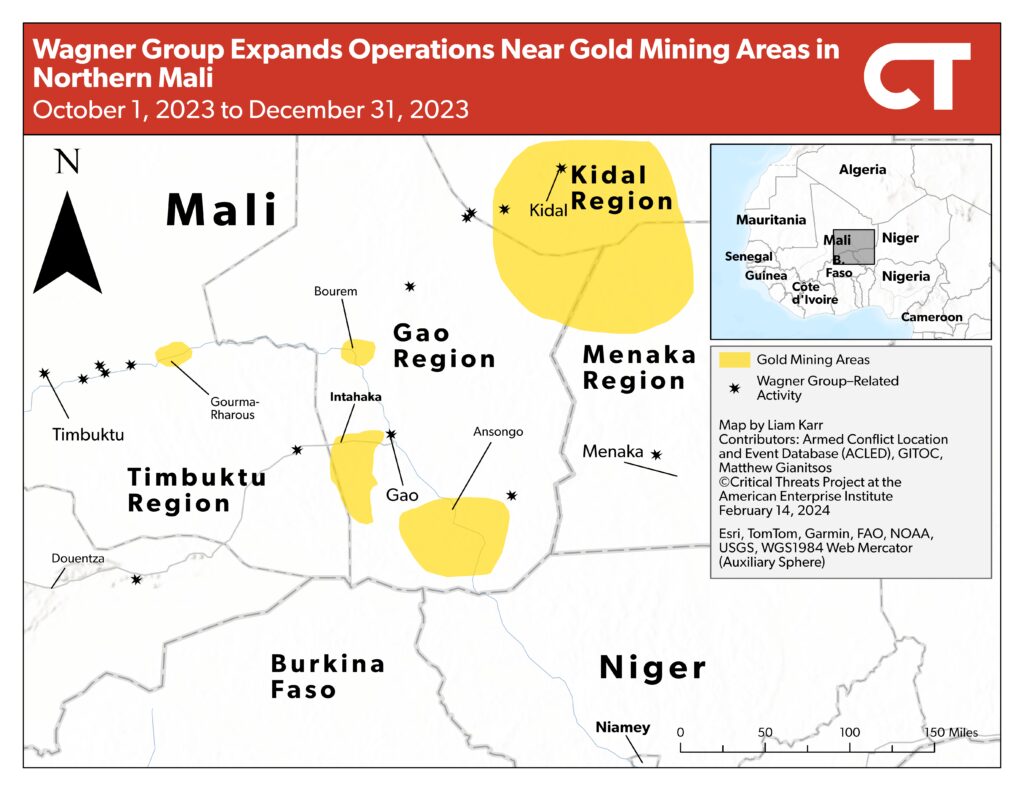

The Wagner Group and Malian army took control of an artisanal gold mine in northeastern Mali, which will bolster the Kremlin’s sanctions evasion efforts. Wagner and Malian forces captured the Intahaka mine in Mali’s Gao region on February 9.[1] The mine is the largest artisanal mine in northern Mali. Multiple armed groups—including the regional al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates—have controlled and taxed the mine in recent years.[2]

Wagner has expressed interest in Malian gold since arriving in the country in 2021 but has been unsuccessful in displacing international companies from Mali’s large-scale mines in the southern part of the country.[3] The taxes that Western mining companies pay to the Malian government have helped the junta fund Wagner’s $10 million monthly contract, however, streamlining Wagner’s process of refining and selling gold to get cash.[4] The artisanal gold mine in Intahaka is the first gold mine in Mali that Wagner has secured control over.

The Blood Gold Report assessed in December 2023 that the Kremlin had generated $2.5 billion from Wagner’s blood gold ventures in Africa since invading Ukraine in February 2022.[5] Much of this money comes from the Central African Republic (CAR) and Sudan, where Wagner has secured mining concessions.[6] The Consumer Choice Center and 21Democracy—a nonprofit that tracks corruption and advocates government transparency—funded the report.[7] Wagner uses middlemen and front companies to exploit gaps in Western sanctions and sell the gold in global markets, mitigating the impact of Western sanctions on the Kremlin.[8]

The Kremlin will likely attempt to expand its influence over northern Mali’s artisanal gold mining sector in the coming year to replicate the indirect purchase model Wagner has used to generate billions from artisanal mines in Sudan. The Wagner Group expanded its area of operations in northern Mali in the fourth quarter of 2023 as it captured separatist rebel-held areas alongside Malian forces.[9] This offensive and subsequent operations have conveniently put the Russian mercenaries closer to the hundreds of unregulated artisanal gold mines in northern Mali’s Gao and Kidal regions that the rebels had controlled.[10] The Kremlin signed a nonbinding memorandum of understanding with the Malian junta in November 2023, as Wagner’s expansion into northern Mali unfolded, to finance and build a gold refinery in the Malian capital.[11] The refinery plans to process 200 tons of gold per year, more than triple the 66.2 tons Mali produced in 2022.[12]

Wagner likely lacks the capacity to control many artisanal mines in northern Mali but can mitigate these capacity issues and secure gold access by cooperating with partner forces, such as the Malian army or pro-government militias. Wagner’s contingent in Mali is only 1,000 personnel, spread across the entire country.[13] The Wagner mercenaries that helped capture Intahaka departed the day after arriving and left the mine in the hands of the Malian army, but they “promised to return.”[14] Pro-government militia fighters that had previously controlled the mine peacefully cooperated with Wagner and Malian forces and are still in the vicinity.[15]

Figure 1. Wagner Group Expands Operations Near Gold Mining Areas in Northern Mali

Note: Wagner Group–related activity is defined as all events involving Wagner Group personnel, including Wagner-initiated engagements, attacks on Wagner, and other interactions with civilians.

Sources: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime; and Matthew Gianitsos.

The Kremlin’s actions in Mali follow the playbook it has used in Sudan. Wagner has leveraged relationships with important power brokers in Sudan to establish itself as the main buyer of unrefined gold from largely artisanal miners instead of engaging in direct industrial-scale mining, as it does in the CAR.[16] It then processes this gold at a Wagner-owned refinery before smuggling it out of the country, generating up to an estimated $1.9 billion in 2021.[17] However, the Swiss-based international civil society organization Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime assessed in 2022 that Russian industrial-mining operations could be established in northern Mali “in the near future” if the Kremlin deemed the area profitable.[18] Such a shift would be more consistent with Wagner’s large-scale operations in the CAR.[19]

Malian officials claim that Mali’s artisanal mines generate 26 tons of gold per year.[20] Most artisanal gold—60–73 percent—comes from southwestern Mali, amounting to $1.23 billion, according to 2019 figures.[21] The lack of state control in northern Mali has made it hard to accurately assess how much gold the region produces, however. Wagner is not active in the gold-rich regions of southwestern Mali, but the expansion of al Qaeda–linked activity closer to these gold mining areas in 2023 presents a potential pretext for future Wagner expansion.

Figure 2. Al Qaeda– and Wagner Group–Related Activity Near Gold Mining Regions in Southwestern Mali

Note: JNIM stands for Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen, al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate. Wagner Group– and JNIM-related activity is defined as all events involving Wagner Group or JNIM personnel, including events where the groups are initiators, targets, or otherwise interacting with civilians.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database; and Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

Somalia.

Al Shabaab claimed an attack in Mogadishu that killed several Emirati military officers in Mogadishu, which is part of the group’s campaign against the UAE for its role in training Somali forces. An al Shabaab defector who had recently joined the Somali National Army conducted an attack at the General Gordon military base, which is run by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in Mogadishu on February 10.[22] The newly trained soldier opened fire on the military trainers and officials when they started praying, killing four Emirati trainers and a Bahraini officer and wounding several Somali soldiers.[23] Al Shabaab claimed the attack in support of Palestine, said that the UAE is “the right arm of the Zionist-Crusader alliance,” and claimed that the UAE’s actions in Somalia aimed to destroy Somalia’s chances of independence.[24]

This is the first time al Shabaab has inflicted casualties on Emirati forces in Somalia. The group had targeted the General Gordon military base and Emirati-trained Somali soldiers in Mogadishu in 2023, however, including three suicide attacks.[25] Al Shabaab has previously used undercover “defectors” to infiltrate Somali government and military institutions from where they can gain information and facilitate or carry out attacks.[26]

Emirati military personnel in Somalia are helping train thousands of Somali soldiers to combat al Shabaab. The Emirati training is part of a military cooperation agreement between Somalia and the UAE that began in 2014.[27] The UAE paused cooperation in 2018 after Somali forces seized an Emirati plane with $9.6 million on board, which inflamed preexisting tensions due to Somalia’s neutrality on the Gulf states’ blockade of Qatar.[28] The program expanded in 2022 when Hassan Sheikh Mohamud returned to the Somali presidency and repaired the partnership he built during his first term from 2012 to 2017.[29]

The training program is a key part of the Somali Federal Government’s (SFG) plans to strengthen Somali security forces before the scheduled withdrawal of African Union troops at the end of 2024.[30] At least two Emirati-trained Somali battalions deployed in Mogadishu have helped improve security in the capital throughout 2023, decreasing overall al Shabaab attacks and fatalities inflicted compared to 2022.[31] The UAE also provides salaries for some of these forces.[32] Al Shabaab targeted these Mogadishu-based UAE-trained Somali forces several times in 2023 and highlighted these attacks as targeting “Emirati mercenaries” in its media publications.[33]

Al Shabaab is also conducting attacks in Mogadishu to intimidate local businesses as part of the group’s operations to extort revenue from Somali civilians. Al Shabaab carried out three attacks against businesses in Bakara Market in December after warning that it would target businesses complying with a government mandate to install closed-circuit television cameras to crack down on extortion practices.[34] The group detonated several improvised explosive devices (IED) targeting the market on February 6, several blocks away from demonstrations against al Shabaab’s taxation and extortion practices.[35] Al Shabaab had tried to detonate an IED in the market on December 3, but security forces thwarted the attack.[36] The group also targeted the assets and employees of the Hormud telecom company at least three times in Mogadishu in mid-December.[37] Analysts suspect al Shabaab targeted the company because it refused to pay taxes to the group.[38]

Al Shabaab makes $100 million in annual revenue, which helps the group finance its war machine and support al Qaeda’s global goals, including attacking the United States and its interests. The US government and military assess that al Shabaab is “the largest, wealthiest and most lethal al-Qaeda affiliate in the world.”[39] The group extorts merchants in areas outside their direct control, such as Mogadishu, by threatening to attack homeowners and businesspeople if they do not pay a property tax.[40] Al Shabaab also has an extensive checkpoint taxation system along key roads throughout southern Somalia, and it taxes citizens living in areas under its direct control.[41]

Al Shabaab’s $100 million annual revenue helps it finance military procurements, provide funding to the al Qaeda core, and support plots to attack the United States and its interests. The UN said in a July 2022 report that the group spends approximately $24 million on weapons and explosives in Somalia annually.[42] The UN also noted in the same report that one member state asserted that al Shabaab supports al Qaeda financially.[43]

Al Shabaab’s stable financial situation also allows it to support external attack plots. The group demonstrated its intent to target the United States and its capability to support attack cells outside of East Africa when the FBI thwarted an al Shabaab–directed 9/11-style terror plot targeting the US homeland in 2019.[44] US investigators linked the plot to a global al Qaeda campaign that the group and its affiliates launched in response to the United States moving its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.[45]

Al Shabaab exploits the SFG’s weak financial regulation enforcement mechanisms to raise and move money with relative impunity. Al Shabaab abuses loopholes in the enforcement of efforts to stop money laundering, counterterrorism finance protocols, and the national identification system to use Hawala providers or formal banking institutions with little traceability.[46] The group uses Hawala transfers—a loosely regulated, semi-informal system of international money transfer often used in environments without full access to the formal banking system—to move most of its funds.[47]

The UN assessed in January 2024 that al Shabaab’s financial capacity “remains undiminished” despite SFG and international partner efforts to degrade al Shabaab’s financial networks since 2022.[48] The SFG claims it has closed hundreds of al Shabaab–linked bank accounts and dozens of mobile money-transfer accounts since 2022.[49] The group has adapted to new regulations on mobile money transfers and large transfers by demanding more cash payments and sending more transfers of smaller sums.[50] Al Shabaab has also forced some money-transfer operators to not comply with laws and sanctions with threats, and many other operators still cooperate with the group without threats because they rely on al Shabaab’s lucrative business to survive.[51]

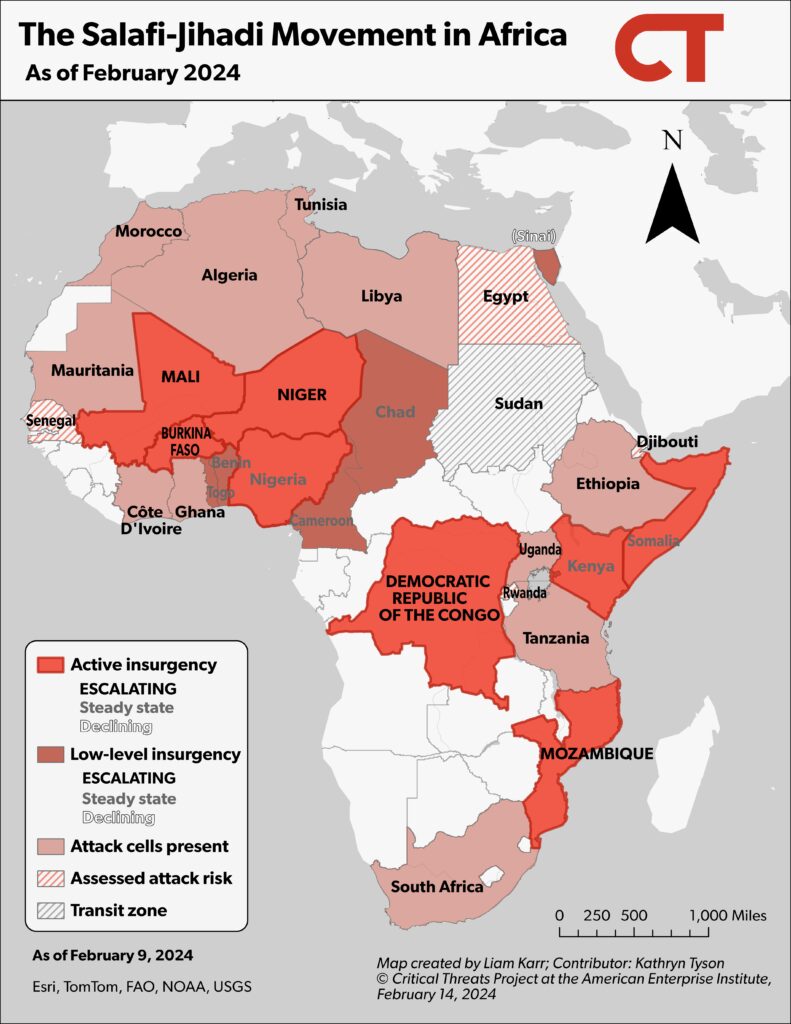

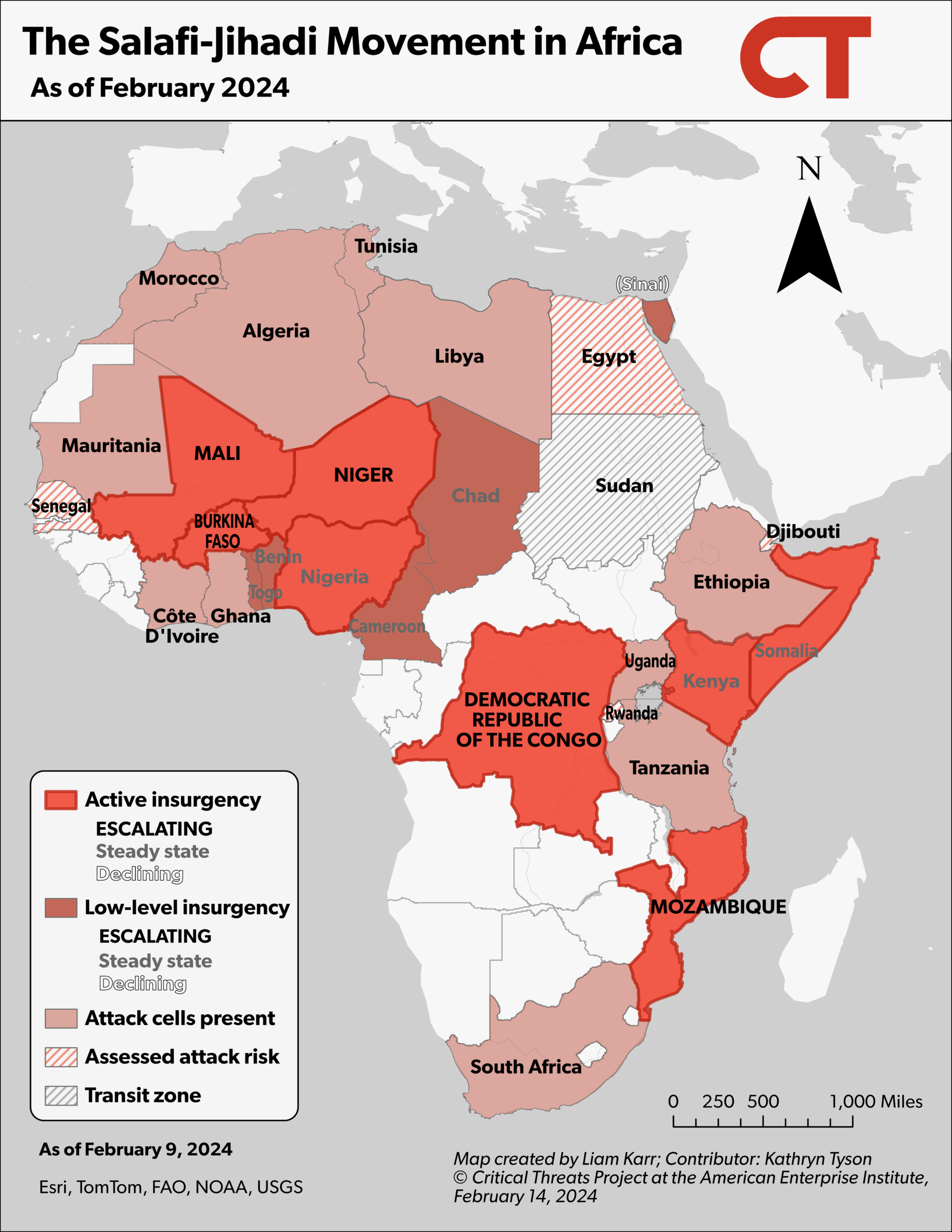

Figure 3. The Salafi-Jihadi Movement in Africa