Data Cutoff: January 26, 2024, at 9 a.m.

Key Takeaway: The US secretary of state met with key US partners in West Africa as Russia and Iran are bolstering their ties with authoritarian regimes in the region. Russia and Iran have capitalized on the rise of a bloc of anti-Western Sahelian juntas that overthrew Western partner states to advance their strategic aims of destabilizing Europe, mitigating Western sanctions, and diminishing Western influence worldwide. The growing Russo-Iranian partnerships with the authoritarian regimes have also enabled brutal and ineffective counterinsurgency strategies that have strengthened the regional Salafi-jihadi insurgency and undermined US regional counterterrorism interests.

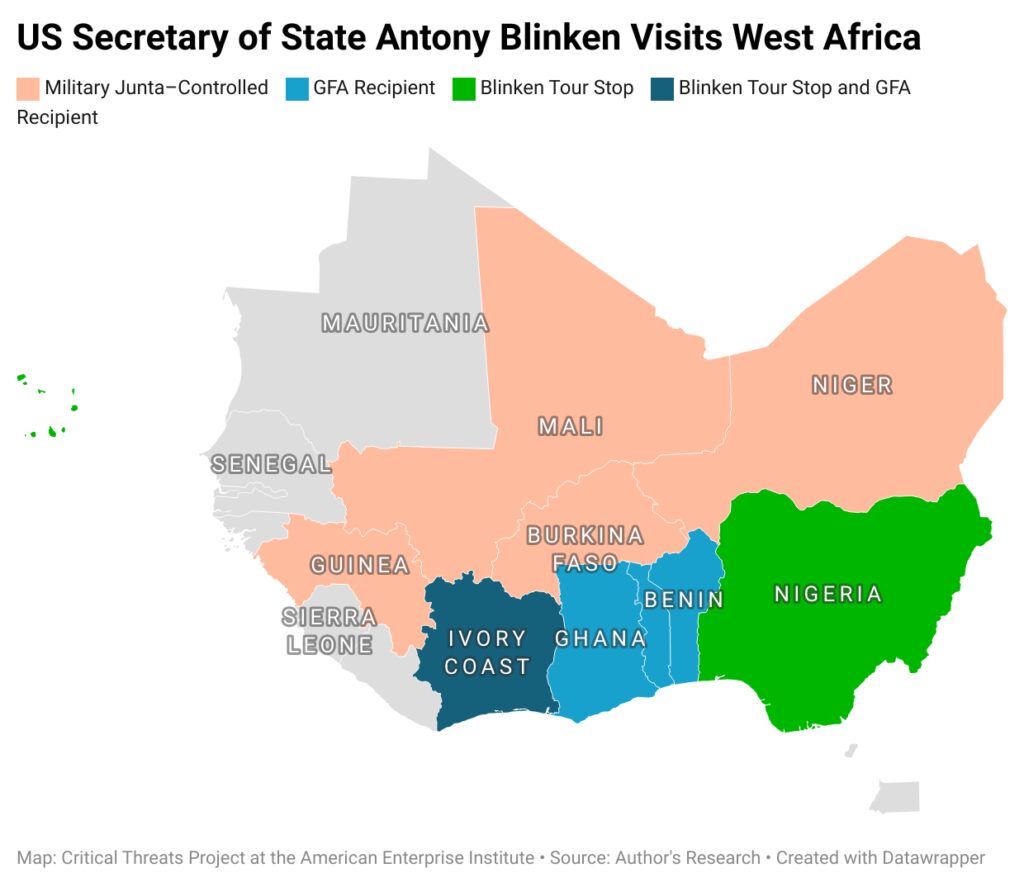

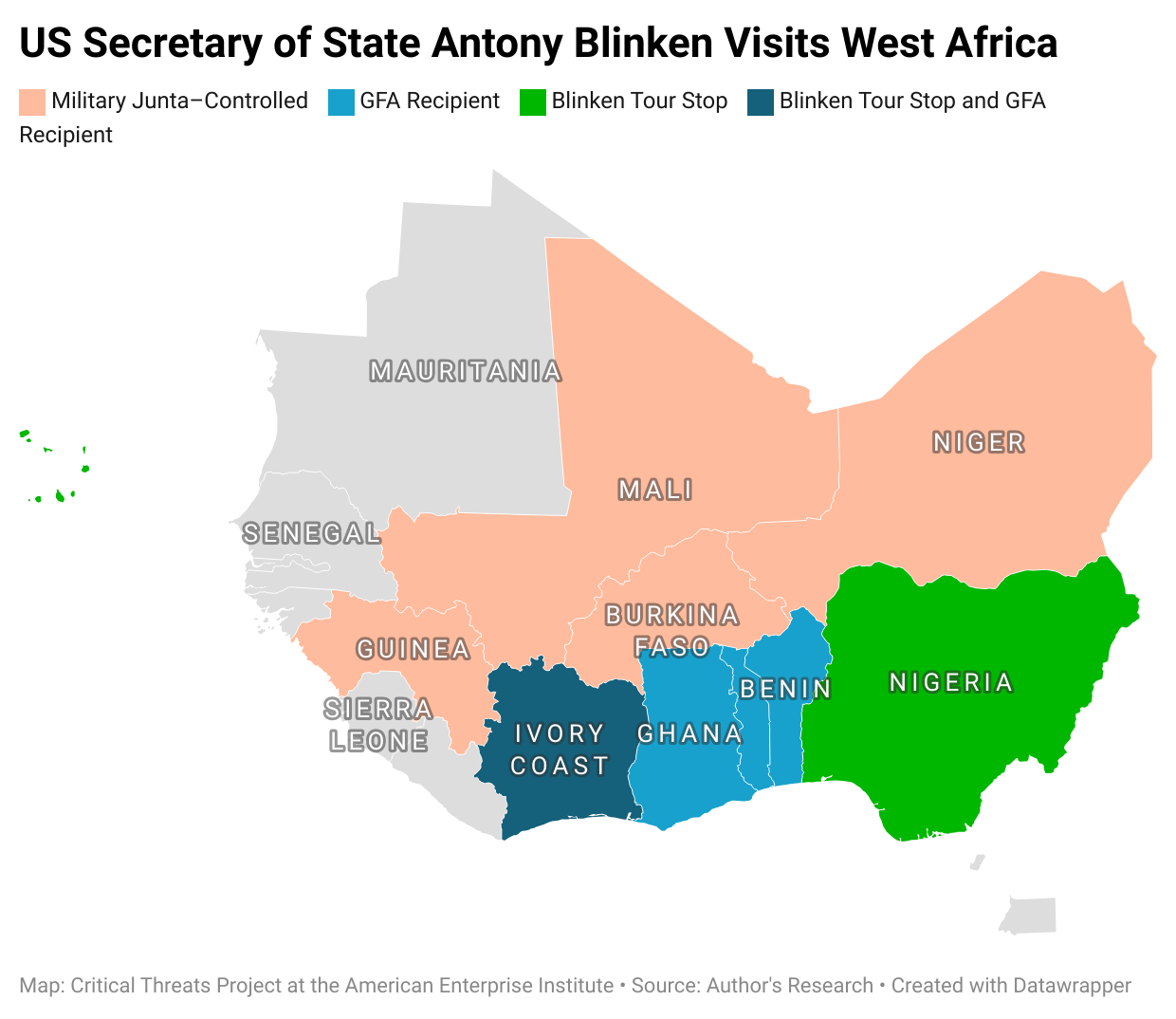

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken met with key US partners in West Africa amid growing threats to strategic US interests from Russo-Iranian entrenchment in the region through partnerships with nascent military regimes. Niger’s military overthrew its president and installed a military junta less than five months after Antony Blinken visited the country during his March 2023 trip to Africa.[1] Military regimes had already taken power in two of Niger’s neighbors—Burkina Faso and Mali—in 2021 and 2022, respectively.[2] The new Sahelian juntas have expanded economic and military relationships with each other, Iran, and Russia. These partnerships advance Russia and Iran’s efforts to destabilize Europe, mitigate Western sanctions, and diminish the West’s global economic and political influence. Russia and Iran have simultaneously failed to adequately replace Western economic and military engagement while amplifying security force abuses against civilians, which has worsened the regional Salafi-jihadi insurgency and threatened US counterterrorism interests.

Blinken returned to Africa on January 22 to meet with Ivorian and Nigerian officials and visit Cabo Verde and Angola to discuss shared economic and security interests.[3] Blinken criticized Russia’s exploitation of people and resources in the Sahel and highlighted US support to fight insecurity by strengthening partner forces with equipment and technology, intelligence sharing, technical support, and civilian-focused security during a press conference in Nigeria on January 23.[4] The secretary and other State Department officials have repeatedly emphasized the importance of restoring and bolstering democracy and strengthening security partnerships to improve security in the region.[5] Blinken made almost identical comments warning against Russia’s track record and encouraging democracy following talks with the now-deposed Nigerien democratic administration in the previous 2023 visit.[6]

The Sahelian juntas have taken advantage of anti-Western sentiment to build partnerships with like-minded authoritarian regimes in Iran and Russia, seeking to mitigate the effects of Western and regional sanctions and the loss of Western aid. The juntas linked popular domestic anti-Western sentiment and postcoup punitive measures from the West and regional democracies with the failure of Western-backed counterinsurgency efforts.[7] This tactic generated popular support in each country for expelling Western and Western-backed forces.

France and the UN peacekeeping mission—which had collectively deployed over 20,000 soldiers to the Sahel to stem the Salafi-jihadi insurgency—withdrew from Mali at the junta’s request in 2022 and 2023, respectively.[8] France withdrew from Burkina Faso and Niger in 2023 following similar demands from the juntas.[9] Niger also ended security and defense partnerships with the EU in December 2023. Niger and Burkina Faso left the EU, UN, and African Union–funded Sahel G5 Joint Force that aimed to enhance regional counterterrorism coordination.[10] The United States, which is the other major Western military partner in Niger, has voluntarily reduced its force presence from 1,000 to 650 troops since September 2023 and is exploring alternative basing in the Gulf of Guinea that could replace its two bases in Niger.[11]

The Sahelian juntas have looked to Russia as an alternative security partner to the West, as it is more aligned with their callous authoritarian approaches to counterinsurgency and regime protection. The juntas contend that Russia has given them greater access to the military hardware they need to defeat the regional Salafi-jihadi insurgency than the West, including auxiliary forces such as the Kremlin-funded Wagner Group mercenaries that have operated in Mali since 2021.[12] The Kremlin provides such access to these regimes because it attaches fewer human rights requirements on its aid and is less concerned about security force abuses, which have spiked since Russia replaced the West as the primary partner in Mali.[13] The juntas also view Russia as a regime security provider. The Burkinabe and Nigerien juntas sought Russian mercenaries to help defend against immediate threats to their power—a coup and regional military intervention, respectively.[14]

The Sahelian juntas have also turned to Iran and Russia for economic development and cooperation to alleviate the effects of Western and African sanctions. The Burkinabe and Malian juntas increased the scope of their bilateral collaboration with Russia in several non-security sectors during the last quarter of 2023.[15] Burkina Faso and Niger also signed several non-security agreements with Iran in October 2023 and January 2024, respectively.[16] Iran and Russia have echoed the juntas’ anti-Western rhetoric to frame this support as a broader fight against Western “colonialism” and “unjust” Western sanctions.[17] The Sahelian countries also joined a mutual defense pact called the Alliance of Sahel States in 2023 under this same rhetorical framing to similarly increase multilateral cooperation with each other and deter potential interventions to reinstitute democracy to strengthen their regime security.[18]

Iran and Russia see North Africa and the Sahel as a means to advance their strategic aims of destabilizing Europe. Iran and Russia are using their partnerships in North Africa and the Sahel to establish an irregular military footprint that poses a risk to NATO’s southern flank via the Mediterranean. Russian mercenary activity in Libya has led to Russian-backed attacks on US drones in the area.[19] Russia has also used its conventional and irregular footprint in Syria to threaten and undermine US forces operating against Islamic State militants, underscoring the threat of Russian military presence near US and allied areas of operation.[20]

Iran has tried to establish its own irregular presence in North Africa by sending drones to separatist forces in the disputed territory of Western Sahara, on the northwestern coast of Africa.[21] Iranian support for the separatists creates the risk of a proxy force that Iran could use to harass Western shipping and military activity in the Mediterranean, similar to how the Houthis are using Iranian weapons systems to wreak havoc on the Red Sea from Yemen.[22] The growing Iranian-Russian footprint in the Sahel creates more opportunities to directly project pressure onto the Mediterranean from the northern reaches of the Sahelian countries and support their ongoing activity in North Africa.

Iran and Russia are also feeding insecurity in the Sahel, which is contributing to potentially destabilizing migration influxes from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa, Europe, and even the United States.[23] The EU has repeatedly emphasized migration as a strategic issue, and Russian President Vladimir Putin has previously weaponized migrant crises to destabilize Europe.[24] Iran and Russia’s backing of the authoritarian regimes has further supported and emboldened brutal and ineffective security strategies that have strengthened the Salafi-jihadi insurgency and amplified security force human rights abuses.[25] The Armed Conflict Location and Event Database (ACLED) found that civilian fatalities in the Sahel increased by 38 percent in 2023, continuing an exponential rise in violence affecting civilians that security forces directly and indirectly contribute to.[26] Insecurity and violence against civilians will continue to grow these migration flows to North Africa and Europe, which risks a destabilizing impact on fragile North African countries that would further surge migration flows and have a ripple effect across the Mediterranean to Europe.[27] The Nigerien junta lifted a controversial EU-backed migration deal in December 2023 that will increase already record-high migration from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa and Europe.[28]

Iran and Russia are also using cooperation with the Sahelian juntas to weaken Western global influence by undermining the coercive strength of Western efforts to economically and politically isolate authoritarian states, which degrades the US’s ability to achieve its global democratic and security interests. The partnerships undermine Western efforts to economically isolate Iran, Russia, and other unfriendly authoritarian states by helping all countries mitigate sanctions. Iran and Russia seek to gain access to valuable natural resources, such as gold, that help them mitigate the effect of Western sanctions from their partnerships with African countries. The various Russian mercenary groups that have deployed to the Sahel have all sought to gain access to these resources directly or through political arrangements.[29]

Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps and regime-affiliated outlets have repeatedly encouraged increased economic engagement with Africa to obtain gold payments that Iran can use to evade sanctions as part of its “neighborhood policy.”[30] Burkina Faso and Mali are among the top five gold producers on the continent, and Niger also has major gold mines.[31] US intelligence officials also said that the Wagner Group used the Malian junta as a middleman to circumvent sanctions and acquire weapons for Russian fighters in Ukraine.[32] These partnerships have additionally undermined Western efforts to politically isolate these states by creating a larger anti-Western and antidemocratic bloc in institutions such as the UN, where the juntas voted favorably for Russia on key issues relating to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and could vote similarly on Iranian-backed efforts to isolate Israel and the United States.[33]

Iran and Russia may also seek access to Niger’s large uranium deposits. Niger is the seventh-largest uranium producer in the world and has one active major uranium mine, which provided about 2,020 tons of uranium in 2022.[34] This is equal to about 5 percent of the world’s mining output and almost exactly 100 times more uranium than Iran’s estimated domestic output in 2022.[35] Iran allegedly attempted to acquire uranium from Niger and Zimbabwe as part of its diplomatic push in Africa in 2013.[36]

Iranian attempts to obtain Nigerien uranium are unlikely as it has sufficient domestic uranium mines, mills, conversion facilities, and stockpiles for its current civilian and military needs, but Iran’s growing relationship with Niger still increases the risk it procures Nigerien uranium to accelerate its nuclear programs.[37] Iran is also in the process of operationalizing at least six new mines as part of a 20-year plan that will supply it with enough uranium for civilian and military purposes.[38] The anti-regime outlet Iran International reported that Iran sought to import 800,000 tons of phosphate from Iran-controlled mines in Syria to extract uranium from the ore in 2023, however, although CTP cannot verify this report.[39] More enforceable international regulations and supply-chain obstacles would hamper similar efforts in Niger compared to Syria.

Russia also likely seeks access to Nigerien uranium as part of its efforts to increase strategic leverage over African countries by creating energy dependence through monopolizing nuclear energy.[40] Russian state-owned energy company Rosatom has signed numerous agreements on nuclear education, nuclear energy production, and uranium mining across Africa.[41] This includes two agreements it signed in October 2023 to construct nuclear power plants in Burkina Faso and Mali.[42]

The Nigerien junta has not indicated that it intends to replace the French- and Canadian-based mining companies that currently own the majority shares in nearly all Nigerien uranium mines, including the only active mine.[43] The Nigerien state holds a minority share in all these mines and levies royalty taxes.[44] Burkina Faso and Mali have similarly not evicted Western gold mining companies, although they have used the taxes levied on these companies to fund other security deals with Russia.[45]

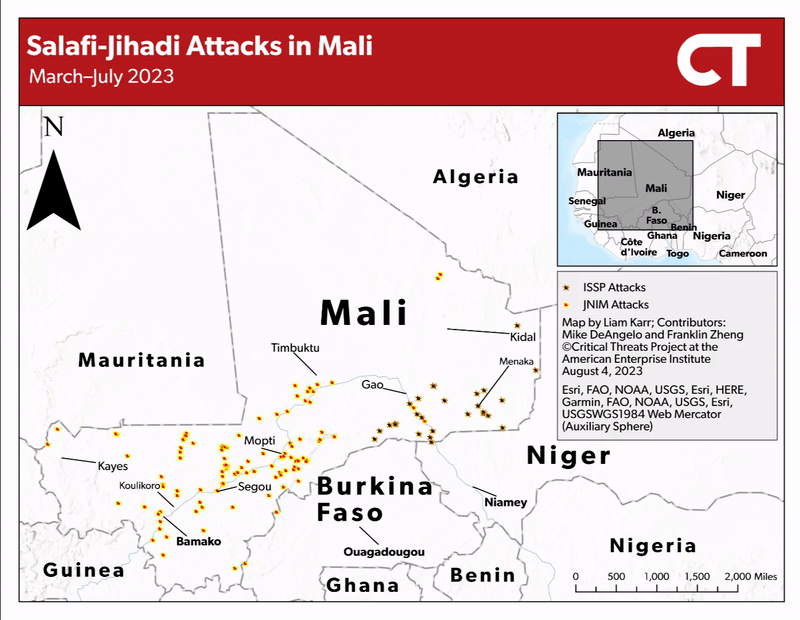

Russia has increased bilateral outreach to the juntas since they took power, especially in the second half of 2023, leading to a slew of economic and military deals that increase the Sahelian juntas’ reliance on the Kremlin. The most visible sign of Russian cooperation has been Russian mercenaries. The Malian junta contracted 1,000 Wagner Group mercenaries in 2021 that have since functioned as auxiliary forces in its fight against Salafi-jihadi insurgents and Tuareg separatist rebels. Wagner was mostly concentrated in central Mali but extended into northern Mali in the last quarter of 2023 to help Malian forces retake areas from Tuareg rebels, conveniently expanding operations near more of northern Mali’s artisanal gold mines.[46]

The Kremlin has stepped up engagement with the Sahelian juntas as part of its effort to replace the Wagner Group after the July 2023 Wagner rebellion and the death of the group’s former leader, Yevgeny Prigozhin, in August 2023.[47] Open-source intelligence organizations have assessed that the Russian Ministry of Defense is ramping up recruitment for a new private military company called “Africa Corps” that aims to establish a foothold in Burkina Faso and Niger and subsume preexisting Wagner operations in other countries such as Libya and Mali.[48]

This outreach accelerated a small but growing Russian mercenary presence in Burkina Faso, with Africa Corps–affiliated Telegram accounts publishing images of 100 mercenaries arriving in Ouagadougou on January 23.[49] The Burkinabe contingent is smaller than the Malian contingent, is focused on regime security and the training of elite units, and has not directly engaged in counterinsurgency operations.[50] Their arrival after two thwarted coup attempts in September 2023 and January 2024 underscores their emphasis on regime security.[51]

CTP previously assessed that Niger may deploy Russian mercenaries to help fill capacity gaps left by the Western departure from Niger and address the escalating Salafi-jihadi insurgency. The Nigerien junta initially showed interest in a Wagner Group deployment in its first days in power, although this was when it faced a potential regional invasion to restore democratic rule.[52] Junta officials have more recently met with Russian defense officials on multiple occasions and signed an unspecified defense agreement with Russia in December 2023.[53] The Nigerien junta vice president additionally met with the Russian deputy defense ministers during a Nigerien ministerial delegation tour in Moscow on January 16 and agreed to “intensify” military cooperation.[54]

Russia has also increased cooperation with the Sahelian juntas in non-security sectors since the second half of 2023. Mali signed numerous agreements with Russian entities on nuclear and renewable energy, mineral extraction, satellite communications technology, petroleum provision, and agriculture following a Malian ministerial delegation trip to Moscow in October 2023.[55] Burkina Faso also signed a nuclear energy deal with Rosatom, and Russia reopened its embassy in Burkina Faso for the first time since 1992 in December.[56] Niger’s more nascent junta has had less time to develop strong formal ties with the junta. Still, Nigerien officials visited Moscow on January 15 to discuss agriculture, energy, and health care with their Russian counterparts.[57]

Iran has also increased bilateral outreach to the juntas, with most attention given to strengthening economic ties. Iranian officials met with their counterparts in the Sahelian juntas throughout 2023. These interactions included Burkinabe, Malian, and Nigerien ministers separately traveling to Tehran to meet with Iranian officials and new cooperation committee meetings with delegations from all three juntas.[58] Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi also emphasized that Iran wanted to work with Niger “especially on economic issues” in October 2023, and Niger and Iran signed agreements on energy, health, and finance in January 2024.[59] Burkina Faso signed several agreements on energy, mining, pharmaceutics, and vocational training with Iran in October 2023.[60]

Iran has increased its engagement across Africa since Iranian President Raisi entered office in 2021.[61] The cooperation is part of Raisi’s “neighborhood policy,” which aims to grow economic ties with non-Western partners to undermine Western sanctions and enable Iran to de-emphasize rapprochement with the West.[62] Raisi was the first Iranian president to visit Africa since 2013 when he traveled to Kenya, Uganda, and Zimbabwe in July 2023.[63]

Iran is also looking to grow security ties with the juntas and could offer its drones as cheaper alternatives to the Turkish drones the juntas currently use. Mali agreed to strengthen defense and security ties with Iran after a meeting between the Malian defense minister and the Iranian ambassador in October 2023.[64] Iran also signed an unspecified defense agreement with Burkina Faso in October 2023.[65]

Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have all deployed at least six Turkish TB2 Bayraktar drones to fight against Salafi-jihadi insurgents since 2022.[66] New partnerships with Iran would open up cheaper alternatives, however, as Iranian drones are a fraction of the cost of TB2s.[67] Iran and Russia are also cooperating to increase the production of Iranian drones for Russia’s war in Ukraine, which creates opportunities to manufacture more drones for other theaters.[68] Iran has sent Ababil-3 multi-role and Mohajer-6 multi-role drones to Ethiopia, Sudan, and Western Sahara since 2021, setting a potential precedent for future shipments to the Sahel.[69]

Iran and Russia’s overlapping interests in Africa create potential avenues for future Russo-Iranian cooperation. Iran and Russia have opportunistically collaborated when they have overlapping interests in areas like Syria and significantly increased cooperation since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[70] Both countries have also worked together to strengthen regime security apparatuses in their own countries, with Russia sending Iran communication surveillance capabilities, eavesdropping devices, advanced photography devices, and lie detectors since 2022.[71] They now have a shared interest in propping up like-minded anti-Western authoritarian regimes in the Sahel, which enables future cooperation in providing military equipment or regime security apparatuses to the friendly Sahelian juntas.

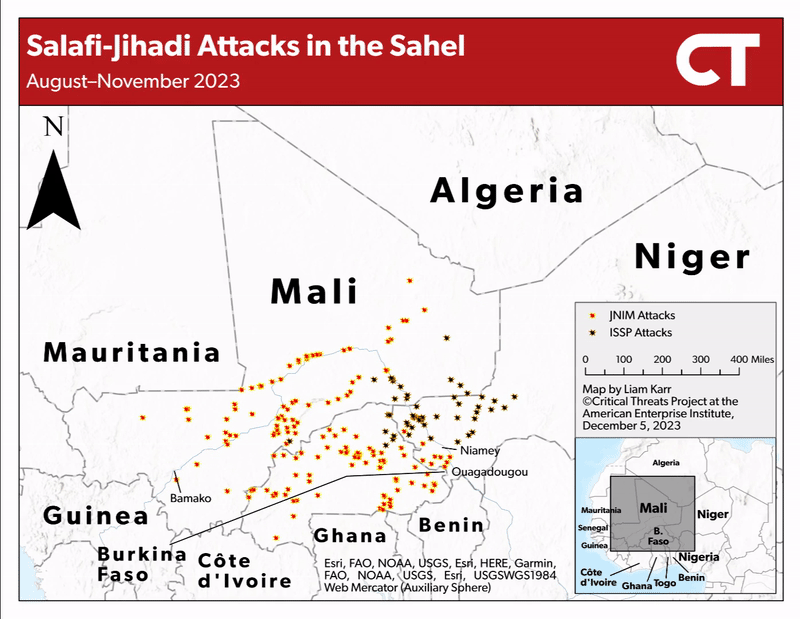

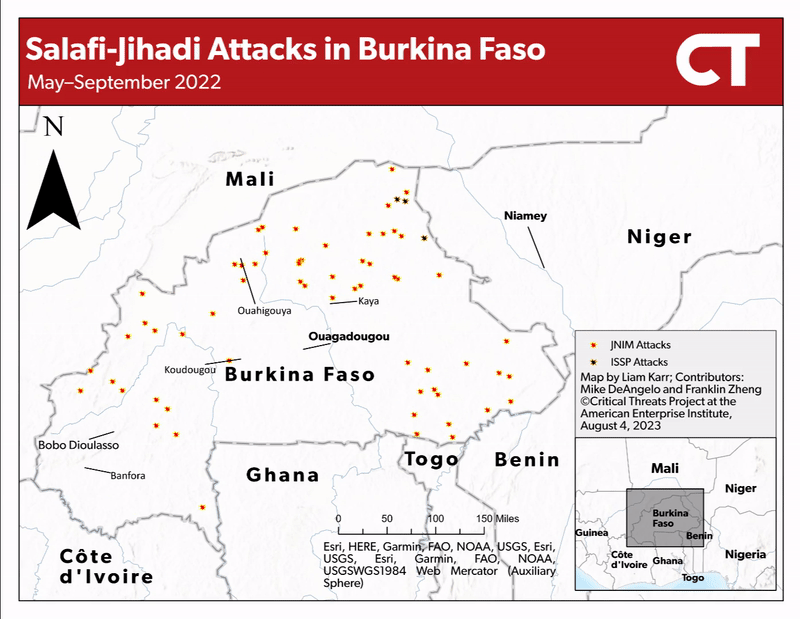

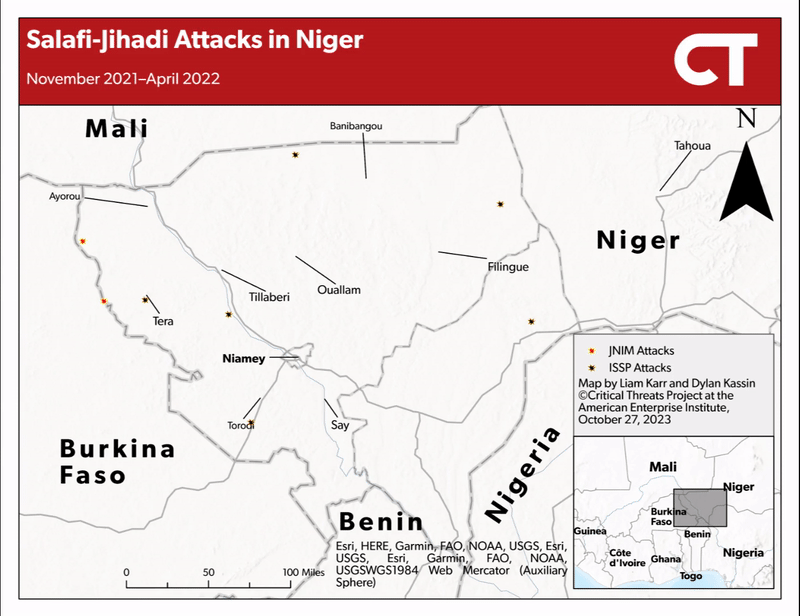

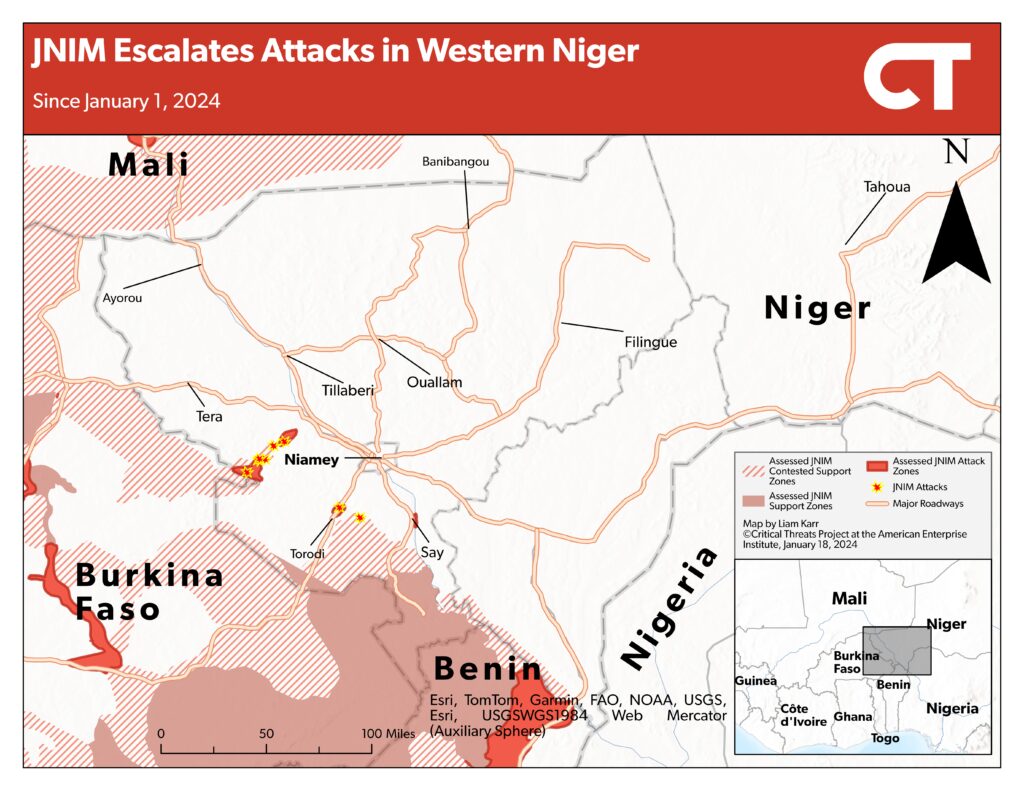

Iranian and Russian assistance has failed to adequately replace Western support and emboldened brutal and counterproductive counterinsurgency strategies, allowing the regional Salafi-jihadi insurgency to strengthen. The Wagner contingent’s size is insufficient to address the insurgency in Mali, given its force composition is roughly 6 percent of the struggling French and UN troops it replaced.[72] Increased drone usage in all three countries has made it more dangerous for militants to gather, but state security forces lack the capacity to retake territory.[73] Al Qaeda– and Islamic State–linked groups are taking advantage of these shortcomings to strengthen their support zones and expand toward political centers in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.[74]

Note: “JNIM” is al Qaeda–affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen. “ISSP” is the Islamic State’s Sahel Province.

Note: “JNIM” is al Qaeda–affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen. “ISSP” is the Islamic State’s Sahel Province.

Note: “JNIM” is al Qaeda–affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen. “ISSP” is the Islamic State’s Sahel Province.

Note: “JNIM” is al Qaeda–affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen. “ISSP” is the Islamic State’s Sahel Province.

The Russian-backed counterinsurgency strategies have further exacerbated the conflict by amplifying security force abuses through indiscriminate violence and collective punishment tactics.[75] The Salafi-jihadi militants use such abuses to pose as protectors and recruit more people to their cause.[76] The juntas’ approaches have also retained critical failures in the Western counterinsurgency approach around addressing poor governance and local political dynamics.[77] ACLED found that 2023 was one of the deadliest years in the Sahel since the insurgency began in 2012, thanks in part to an increase in insurgent and security force attacks on civilians.[78]

Worsening insecurity in the Sahel will undermine US regional counterterrorism interests with partners like Côte d’Ivoire and Nigeria in coastal West Africa and increase the Salafi-jihadi groups’ transnational threat risk. Stronger Salafi-jihadi insurgencies in Burkina Faso and Niger will amplify pressure on vital US counterterrorism and economic partners in littoral West Africa.[79] This risks overwhelming US efforts to insulate Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Togo from a cross-border insurgency through the Global Fragility Act (GFA).[80] Growing Salafi-jihadi control over parts of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger will also increase the transnational threat risk by giving IS and al Qaeda militants the resources and space to plot attacks against neighboring African states—or attacks in Europe, should they choose to do so.