African, Latin American, and Caribbean countries can enhance the benefits of their engagements with China by expanding coordination and lessons sharing to ensure that citizens’ interests are prioritized.

2024 is a pivotal year for China and the Global South. China continues to make an active diplomatic push for influence in the developing world with a strong presence at the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit and the Third South Summit of the Group of 77 Plus China, in Kampala, Uganda early in the year. These meetings will kickstart preparations for the ninth Forum for China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the fifth China-Latin American and Caribbean Forum (China-CELAC) summits in mid-2024.

China positions itself as a champion of the Global South. Beijing’s foreign policy is guided by the doctrine “Big powers are the key, China’s periphery the priority, developing countries the foundation, and multilateral platforms the stage.”

China is Africa’s largest trading partner and the second largest for Latin America. Its portfolio of engagements comprises access to markets, infrastructure, energy, strategic minerals, digital infrastructure, space, security, and party-to-party exchanges. Many Global South states vote alongside China in multilateral bodies.

When engagement by civil society, courts, and other independent institutions is robust, then governments and their Chinese partners can be held more accountable.While some African, Latin American, and Caribbean countries have realized positive outcomes from their engagements with China, others such as Angola, Ecuador, Venezuela, Argentina, Ethiopia, and Zambia have faced mounting debts. Further downsides include environmental damage, human rights violations (particularly in the extractives industries), weakened due diligence and oversight, corruption, and elite capture.

In recent years, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Zambia, Ethiopia, and Kenya have sought debt relief from China with mixed success. The environmental risks of major Chinese investments are also a key concern to civil society in the Global South. A study by the Business and Human Rights Resource Center found that 76 percent of recorded allegations of abuse linked to Chinese firms in the Global South between 2013 and 2020, were in the mining, construction, fossil fuels, and renewables sectors. Africa posted the second highest number of allegations.

As some Latin American, Caribbean, and African countries have faced challenges of unconstitutional changes of government, China’s approach has been to strengthen incumbent governments regardless of how they came to office. It does not raise concerns over human rights claiming “non-interference.” China’s preferred model of engagement, hence, endears it to authoritarians and gives them options they would otherwise not have. Countries that are either heavily sanctioned or isolated from the international system (like Zimbabwe and Bolivia) can count on China’s support as “all weather friends.”

Latin American, Caribbean, and African countries have gained valuable lessons about the importance of due diligence from these engagements over the years. When engagement by civil society, courts, and other independent institutions is robust, then governments and their Chinese partners can be held more accountable.

Institutional Framework: A Mirror-Image with Some Differences

FOCAC and China-CELAC are part of a system of multilateral institutions that China built over the past two decades in an effort to construct an alternative international architecture alongside the current global order. FOCAC, China-CELAC, and similar forums—like the China Arab States Cooperation Forum (CASCF)—are in many ways mirror images of one another—with similar organizational structures, goals, and objectives consistent with China’s ideological values.

FOCAC was established in October 2000 in Beijing, just before China joined the World Trade Organization. It is the oldest of China’s regional forums. The forum took off in 2006, when Beijing announced a $5-billion China-Africa Development Fund and offered interest-free loans and increased aid. Since then, it has evolved into a comprehensive mechanism spanning a host of issues.

The China-CELAC forum—which is modeled on FOCAC—was first announced in 2014, during President Xi Jinping’s visit to Brazil. This was just one year after Xi officially rolled out China’s flagship “One Belt, One Road” strategy (coined as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) for international audiences). Before the forum, China’s engagement with CELAC countries was largely bilateral. The first China-CELAC ministerial meeting was held in Beijing in 2015.

In all, China’s lending in the Global South between 2008 and 2021 represented 83 percent of the World Bank loan portfolio over the same period.Since then, 22 out of the 33 CELAC countries have joined the BRI. In Africa, the BRI has near universal membership (53 countries) with Eswatini the only exception (and the only African country that still recognizes Taiwan). In CELAC, 13 countries recognize Taipei. China is trying to entice them into its orbit, mainly through economic incentives. Since 2017, targeted BRI investments helped flip the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.

China’s effort to create alternative international structures has gained traction. Between 2000 and 2022, African countries accessed $170 billion in Chinese loans via an increasingly complex network of Chinese-created institutions, such as the Silk Road Fund and the Asia Infrastructure Investment Fund. CELAC countries, meanwhile, accessed $130 billion. In all, China’s lending in the Global South between 2008 and 2021 represented 83 percent of the World Bank loan portfolio over the same period. In essence, Beijing’s plethora of new multilateral institutions are offering alternatives, but on less concessional terms than the World Bank, which is why some countries in the Global South see China as a lender of last resort.

Nearly Identical Structures

FOCAC and the China-CELAC Forum meet triennially at the heads-of-state level and release 3-year joint action plans to guide their relations between summits. As of 2024, China had released eight joint action plans for Africa and two for CELAC. China also issues regular national strategies on both regions, such as the China-Africa white papers of 2006, 2015, and 2021, and similar ones for CELAC countries in 2008 and 2016.

FOCAC meetings among senior officials often take place between summits, frequently on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), the African Union (AU), and other forums. These structures are replicated on the China-CELAC side, but since CELAC was established 3 years before China-CELAC, the various sides simply grafted some forum structures onto existing CELAC organs. For instance, in addition to the Ministerial Conference, there are meetings between the Chinese foreign minister and the CELAC “Quartet”–four members holding specific leadership roles in CELAC. FOCAC’s Senior Officials Meeting corresponds with China-CELAC’s National Coordinators’ Meeting since these roles already existed in CELAC. Some China-CELAC meetings also occur during UNGA.

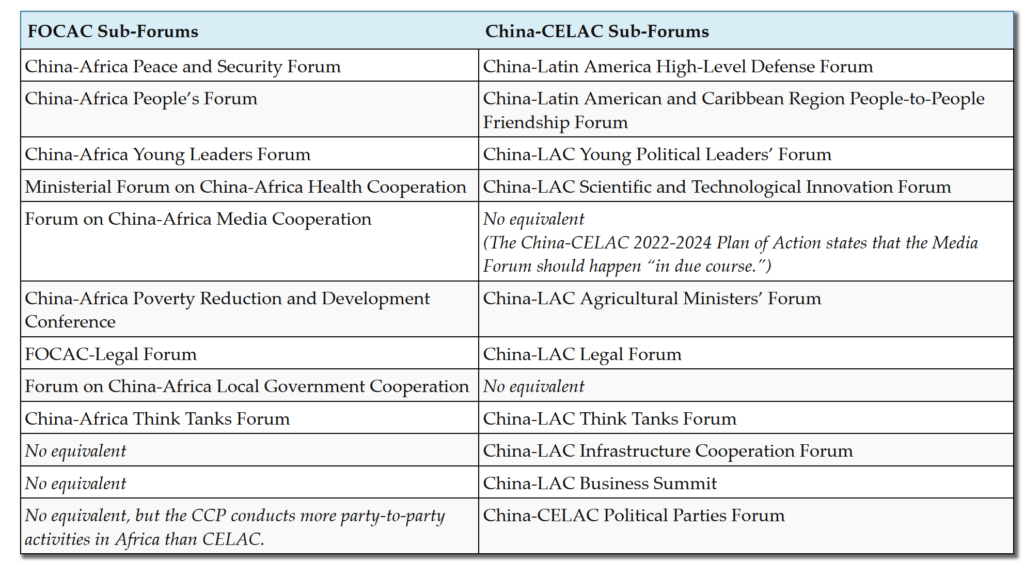

Both groupings have numerous sub-forums (9 for FOCAC and 10 for China-CELAC), creating venues for China to build bridges, cultivate influence, and promote its governance model. They also help expand its partnerships. For example, China’s military ties with CELAC received a boost after the establishment of the China-Latin America High-Level Defense Forum in 2015, when China-CELAC was inaugurated. Since then, China has provided more professional military education training slots for Latin American and Caribbean officers than the United States, by a factor of five to one in some years.

China’s military education quotas in Africa are also on a scale that is unmatched. These are drawn from training slots offered at every summit (approximately 100,000 academic scholarships, media fellowships, and invitations triennially to African countries through FOCAC prior to the pandemic and around 50,000 for CELAC). Both regions send roughly the same number of students to China annually (60,000-70,000), including around 6,000 government officials each.

Some Lessons from Each Region

Both regions play host to the same Chinese institutional actors, from state-owned enterprises, Chinese policy banks, public security, and national defense ministries, to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), security firms, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials, and Confucius institutes.

Many CELAC countries are middle-income economies, presumably giving them greater leverage in securing optimal deals. Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru achieved Free Trade Areas (FTAs) with China, while Ecuador, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama are actively negotiating theirs. Mauritius is the only African country that has a FTA with China, although Kenya has also expressed interest.

Because of the overlap between CELAC and the China-CELAC Forum, Latin American and Caribbean officials have arguably been more successful in negotiating as a bloc.Because of the overlap between CELAC and the China-CELAC Forum, Latin American and Caribbean officials have arguably been more successful in negotiating as a bloc. The CELAC National Coordinators Meeting helps them harmonize positions ahead of China-CELAC meetings. The African side does not have a comparable mechanism, though in recent years, African professionals have offered many proposals for AU members to devise a common strategy towards China.

Both regions have gained experience in citizen advocacy and engagement. One example is the Latin American nongovernmental (NGO) coalition, the Collective on Chinese Financing and Investment, Human Rights and the Environment (CICDHA). In February 2023, it tabled a report at the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, based on field studies of major Chinese ventures that failed to comply with local labor, environmental, and human rights standards in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela.

The Las Bambas copper mine in Peru, operated by Chinese firm MMG, the largest foreign investment in the country to date, is one such example. The Muqui network, an NGO coalition representing over 30 environmental and social justice organizations, documented forced relocations of communities near the mine and also alleged that MMG “modified the environmental impact study” and failed to conduct public consultations prior to the project.

Mindful of the potential reputational hazards, China has acknowledged such claims and promised to establish a grievance mechanism in line with guidelines for preventing environmental risks laid down by Xi Jinping in 2021 in response to escalating public pressure that the BRI faces over environmental, corruption, and other concerns.

Much of the pressure comes from Global South NGOs with access to UN institutions, which China is seeking to influence. Strategic litigation has emerged as a favored tool in Africa, alongside media investigations and policy advocacy. Litigators have worked on delicate cases in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, and Uganda, among others. In Guinea, NGOs involved in monitoring the bauxite industry have partnered with the Center for Legal Assistance to Pollution Victims (CLAPV), China’s first NGO environmental law clinic with a wealth of experience in Chinese litigation. It has trained several African NGOs on how they can apply Chinese legal tools to enforce compliance by Chinese firms operating in their countries.

Such innovation draws on the steady growth of independent China knowledge networks that have developed in Latin America, Africa, and Asia in recent years. The oldest of these, the Chinese in Africa and Africans in China Research Network, boasts an active membership of 1,200 Africa-China thought leaders producing research, sharing connections, and lessons learned. In 2023, African, Latin American, and Caribbean researchers, academics, and practitioners formed the Africa-Americas Forum on China, a first of its kind cross-regional platform to compare and contrast China’s engagement in the AU and CELAC regions, organize its own conferences, and transfer lessons and best practices.

Expanding Coordination between Africa and Latin America

Independent voices from Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean are calling for greater coordination to enhance attention on citizen priorities ahead of the next FOCAC and China-CELAC summits. Specifically:

The AU should convene a senior officials coordination meeting akin to CELAC’s National Coordinators Meeting to help harmonize positions ahead of FOCAC.

Governments should consult NGOs already collaborating and distilling cross-regional lessons. Government representatives should take part in independent civil society forums that will be held ahead of the summits, and beyond.

NGO actors from both regions should intensify their collaboration and facilitate the sharing of experiences to help shape policy priorities.

The AU and CELAC should engage each other more strategically to borrow lessons and develop a global and holistic perspective of Chinese engagement.By convening meetings among senior officials, systematically distilling best practices, consulting with civil society professionals, and relaying those lessons to their foreign ministers, the AU and CELAC can be more effective in advancing their respective citizens’ interest. China often espouses South-South cooperation. By working together, the AU and CELAC stakeholders would be engaging in South-South cooperation of the highest order, maximizing their relationship with China across the Pacific, while improving the lives of their citizens across the Atlantic.