With recent questions surrounding the June 24 election in Sierra Leone, international partners must reevaluate their response to seriously flawed elections.

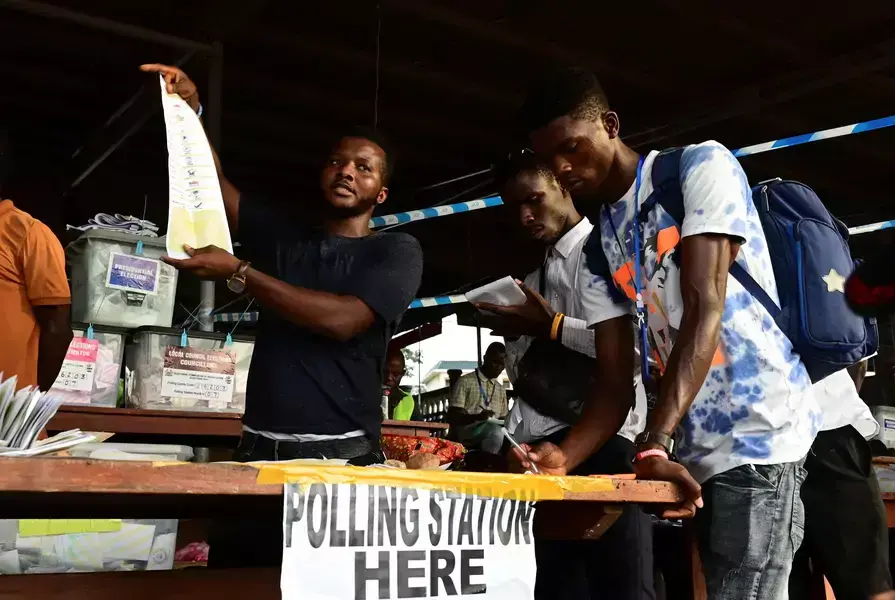

Life has been hard for the people of Sierra Leone. They have been coping with soaring inflation, high rates of poverty and unemployment, and widespread food insecurity. Over the past year, these conditions have triggered popular protests, which were met with a deadly state response. With 67 percent of Sierra Leonians believing their country is headed in the wrong direction, one might have expected a surge of “change” votes in the June 24 general election. Few expected the incumbent to be re-elected in the first round, which required that he garner over 55 percent of the votes cast. Thus, it was somewhat surprising when the Electoral Commission of Sierra Leone announced that incumbent President Julius Maada Bio had been reelected with just over 56 percent of the votes.

Surprise has turned to alarm. International observers, usually quite mild in their assessments, have been pointed in raising concerns about the process. The EU Observation Mission has pointed to “statistical inconsistencies” in reported results. In a joint statement, the United States and several European ambassadors expressed concern about “the lack of transparency in the tabulation process” even as they called for all parties to exercise restraint. Domestic observers with the seasoned organization National Elections Watch found “major disparities” between their Parallel Vote Tabulation and the official results. For their trouble, some of the members of NEW have reportedly been threatened and harassed.

The major opposition party has demanded that elections be re-run. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which has been trying to hold the line on unconstitutional transfers of power in the region in accordance with its Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, but has struggled to respond to murkier problems like third-term bids, has been notably quiet since it issued a preliminary statement on June 26.

If the election was rigged, what is to be done about it? For external actors like the United States, the standard playbook in these situations in to emphasize the importance of calm, and to urge parties to pursue their concerns through the courts. But according to Afrobarometer, just 32 percent of Sierra Leonians trust the courts “somewhat” or “a lot.” Friends of Sierra Leone, and champions of democracy, cannot simply point toward a potential judicial process and then move on.

Elections that are only “peaceful and inclusive” in name but neither free, fair, nor transparent in reality are a problem, not a cause for celebration. They erode support for democracy because they misrepresent it as political theater that has no real relationship to citizens’ ability to hold their leaders accountable for their performance. States that have emerged from horrific conflict, like Sierra Leone, are not well-served by the idea that simply averting conflict is “good enough.” Peace should not be premised simply on a fear of returning to the past, but rather hope for building a better future. With multiple elections approaching in the region, both ECOWAS and Sierra Leone’s development partners need the courage of their convictions. Accepting election results that lack integrity only increases the chances of unconstitutional transfers of power down the line and dims the prospects for sustainable growth. Election-rigging should be met with consequences tough enough to make it undesirable, and civic champions of a fair process—who are channeling the overwhelming popular support for democratic governance—deserve meaningful support.