African states have led the charge against apartheid before. They could also spearhead the boycott of Israel today.

Even by the low standards of a country used to being regularly condemned for human rights abuses, disregarding international law and committing war crimes, February was a pretty bad month for Israel and its standing in the world.

From revelations about its companies subverting democratic elections across the globe to this week’s scenes of its illegal settlers, protected by its army, carrying out a pogrom against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank town of Huwara, the country has had its true face exposed to the world in a cruel and meticulous fashion.

At the opening ceremony of the African Union’s annual summit, held at its headquarters in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia two weeks ago, there was another nasty surprise and more humiliation in store for the Jewish state. Ambassador Sharon Bar-Li, the deputy director of the Africa Division of Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was booted out after turning up, brandishing a non-transferable invitation that had supposedly been issued to Israel’s ambassador to the African Union, Aleli Admasu.

A video posted on social media showed uniformed security personnel escorting her out of the auditorium and Moussa Faki, chairperson of the AU, followed up with a clarification that Israel’s controversial 2021 accreditation as an observer state, which it had pursued for two decades, had actually been suspended and “so we did not invite Israeli officials to our summit”.

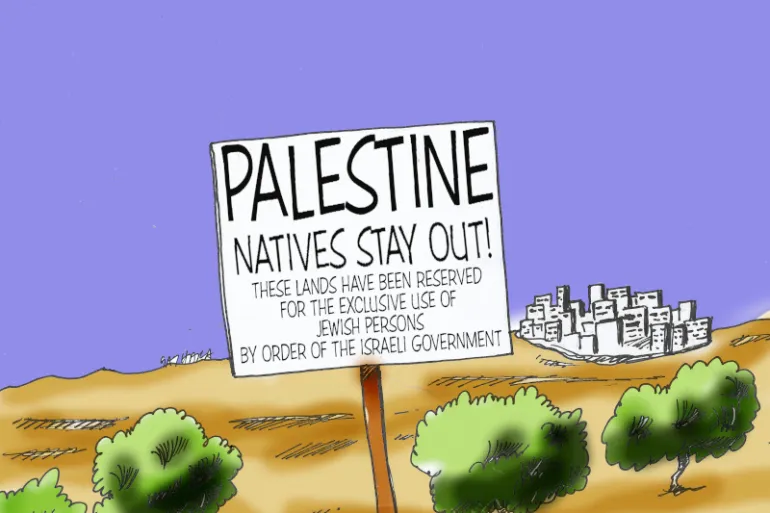

Even worse was to come. According to a Draft Declaration On The Situation In Palestine And The Middle East circulated among reporters at the end of the summit, the AU not only expressed “full support for the Palestinian people in their legitimate struggle against the Israeli occupation”, decrying the “unceasing” illegal settlements and Israel’s intransigence but, significantly, urged member states to “end all direct and indirect trade, scientific and cultural exchanges with the State of Israel”.

This latter recommendation, which echoes the demands of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, if implemented, could be the start of a change in Israel’s fortunes, not just on the continent, but across the globe. After all, Africa is no stranger to leading a global movement seeking to isolate and pressure oppressive, ethno-supremacist regimes, having led one targeting the apartheid regime in South Africa in the 1980s. And, in fact, the draft declaration calls on “the international community … to dismantle and prohibit the Israeli system of colonialism and apartheid”.

That’s tough talk. But whether any action is likely to follow is up in the air. The relationship between Africa and Israel is complex and has fluctuated. Further, the AU’s stance on relations with Israel and the foreign policies of its individual members do not always align. While Israel’s actions towards its neighbours have been a major irritant, they are far from the only consideration for African nations. And in the last 21 years, the AU has tended to be more principled while its member nations have been more pragmatic.

Initially, Israel cultivated close ties with newly independent African countries as a way to counter the isolation and hostility imposed on it by its Arab neighbours. In the 1960s, more than 1,800 Israeli experts were running development programmes on the continent and by 1972, Israel hosted more African embassies than Britain.

It had established diplomatic relations with 32 of the 41 independent African states which were also members of the Organisation of African Unity, the forerunner to the AU, founded in 1963. For much of this period, attempts by the North African nations, led by Egypt, to gain backing for the Arab cause from the rest of Africa had been largely unsuccessful, the relatively young nations not wanting to become enmeshed in the conflict.

But attitudes began to change following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war. African reactions to the conflict were mixed, with some countries such as apartheid South Africa and Ethiopia, which was initially critical, expressing support for Israel and others siding with the Arab states. Overall, however, many African leaders, with memories of colonialism’s acquisition of land by force still fresh, viewed Israel’s actions dimly and on June 8, as the fighting was ongoing, the OAU condemned Israel’s “unprovoked aggression” and called for an immediate ceasefire.

However, the real rupture came in the 1970s and, especially, following the 1973 October war. By then, despite resistance from many countries, the troubles in the Middle East had been inching up the continent’s agenda and generating rifts within a continent that valued consensus and solidarity. At its 1971 summit, the OAU made a half-hearted and ultimately ineffectual attempt to mediate between the Arabs and the Israelis, calling for negotiations and appointing a committee led by Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere to oversee its efforts.

Between March 1972 and the outbreak of war in October 1973, eight African countries broke off relations with Israel. At the 10th-anniversary meeting, tensions over the issue burst into the open. OAU Secretary-General Nzo Ekangaki declared that “as long as Israel continues to occupy parts of the territory of one of the founding members of the OAU, Egypt, she shall continue to have the condemnation of the OAU.” However, many other African states refused to sacrifice their relations with Israel for the sake of this issue, despite the OAU’s urging.

The October war and the resulting oil embargo by Arab states that drove up global oil prices changed that calculus. By November, all but four African states – Malawi, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Mauritius – had abandoned Israel, which thereafter only made matters worse by cultivating a close relationship with the apartheid regime in South Africa, a move that continues to poison its relations with the continent to this day.

Despite the restoration of ties in the 1980s and 1990s, Israel has never regained the stature it had enjoyed two decades prior. While today it has diplomatic relations with more than 40 countries on the continent, it remains locked out of the AU and the vast majority of the 54 African votes at the UN General Assembly are still reliably pledged to the Palestinians.

The push in recent years to improve ties has borne some fruit but has also come up against the tide of history. The fact is, the situation today is akin to that in 1973, with the continent split over how to respond to Israeli oppression, with countries balancing a principled opposition to apartheid with pragmatic economic and security cooperation.

However, a major crisis could shift the balance in favour of the former. What an internal assessment by the Israeli foreign ministry concluded in July of that year rings true half a century later: “Israel’s image as an occupier, its refusal to withdraw from all territories – are not acceptable in Africa, and the Arab demands receive emotional and instinctive support even amongst our friends … There is a danger that these trends will continue to escalate …”.

The events in Addis this February were an indicator of that.