In light of the crisis that unfolded in southern Yemen at the end of 2025, ACLED’s Middle East Regional Specialist explains what happened and how players in the region have reacted.

Long-simmering tensions within Yemen’s Presidential Leadership Council (PLC) escalated in the last months of 2025, as the regional competition between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates trickled down to southern Yemen. Over the span of roughly one month, the crisis led to two sudden reversals in territorial control in the country’s south, driven by confrontations between the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC) and a constellation of Saudi-backed actors. ACLED’s Middle East Regional Specialist, Luca Nevola, explains what happened in Yemen, how players in the region reacted, and what their next steps may be.

What has happened in southern Yemen since December 2025?

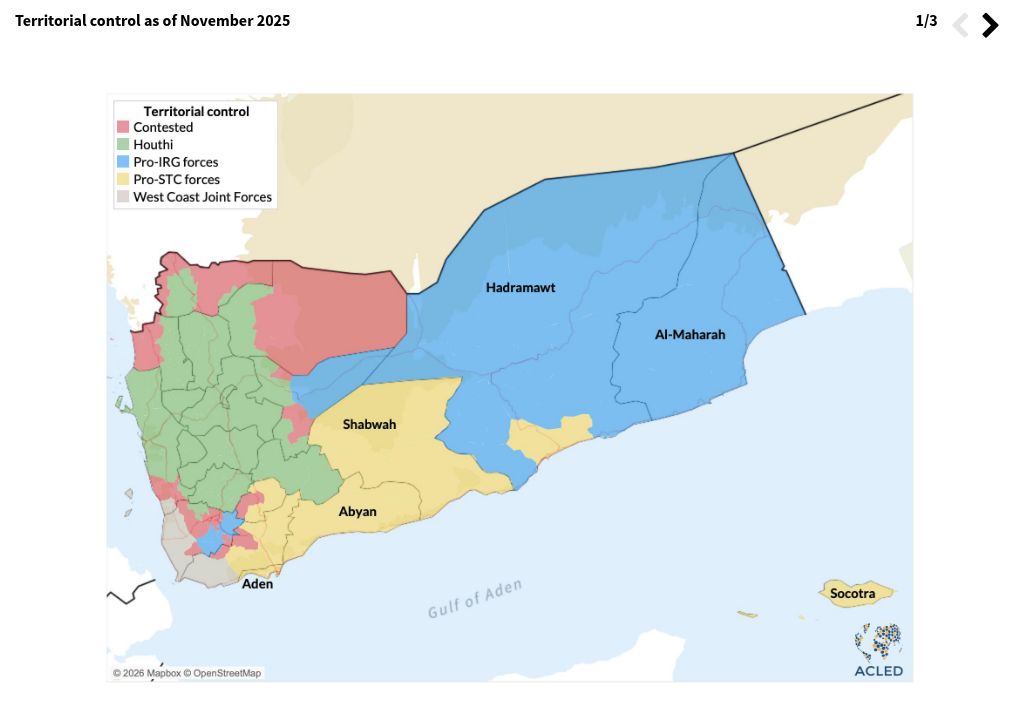

Over the span of roughly one month, the crisis led to two sudden reversals in territorial control in southern Yemen (see map below).

In early December, pro-STC forces advanced inland from the coastal area of al-Mukalla, seizing control of Hadramawt governorate before pushing further east to capture al-Mahra’s capital, al-Ghayda. Subsequently, they made territorial gains in Shabwa governorate and advanced into Abyan under the pretext of fighting terrorist groups. In parallel, Islah’s territorial presence contracted to its lowest level, with the party increasingly isolated in Marib — home to Yemen’s largest oil fields — its supply lines cut, and its positions in Taizz encircled by UAE-backed forces aligned with Tariq Saleh.

These rapid advances fueled fears that the STC could achieve the secession of southern Yemen. Yet the group’s apparent success was ultimately unsustainable, as its ambitions drove it to cross red lines established by Saudi Arabia and Oman by infringing on their border security interests.1

How did Saudi Arabia react to the STC’s advance?

Throughout December, Saudi Arabia exercised restraint through diplomacy, with little effect, as al-Zubaydi effectively rebuffed mediation efforts.2 Riyadh’s approach changed dramatically after its warplanes struck al-Mukalla port on 30 December, accusing Abu Dhabi of backing the STC. PLC President Rashad al-Alimi called for the withdrawal of UAE troops and introduced a state of emergency.3 Between 2 and 4 January 2026, NSF retook Hadhramawt and al-Mahra with support from Saudi airpower, while Aden capitulated on 7 January, resulting in the near-total collapse of the STC’s territorial holdings. Concurrently, the UAE completed a withdrawal of its forces from all Yemeni territory, including the strategic islands of Socotra and Perim.4

Who are the main actors involved in the current crisis, and how are they linked to regional powers?

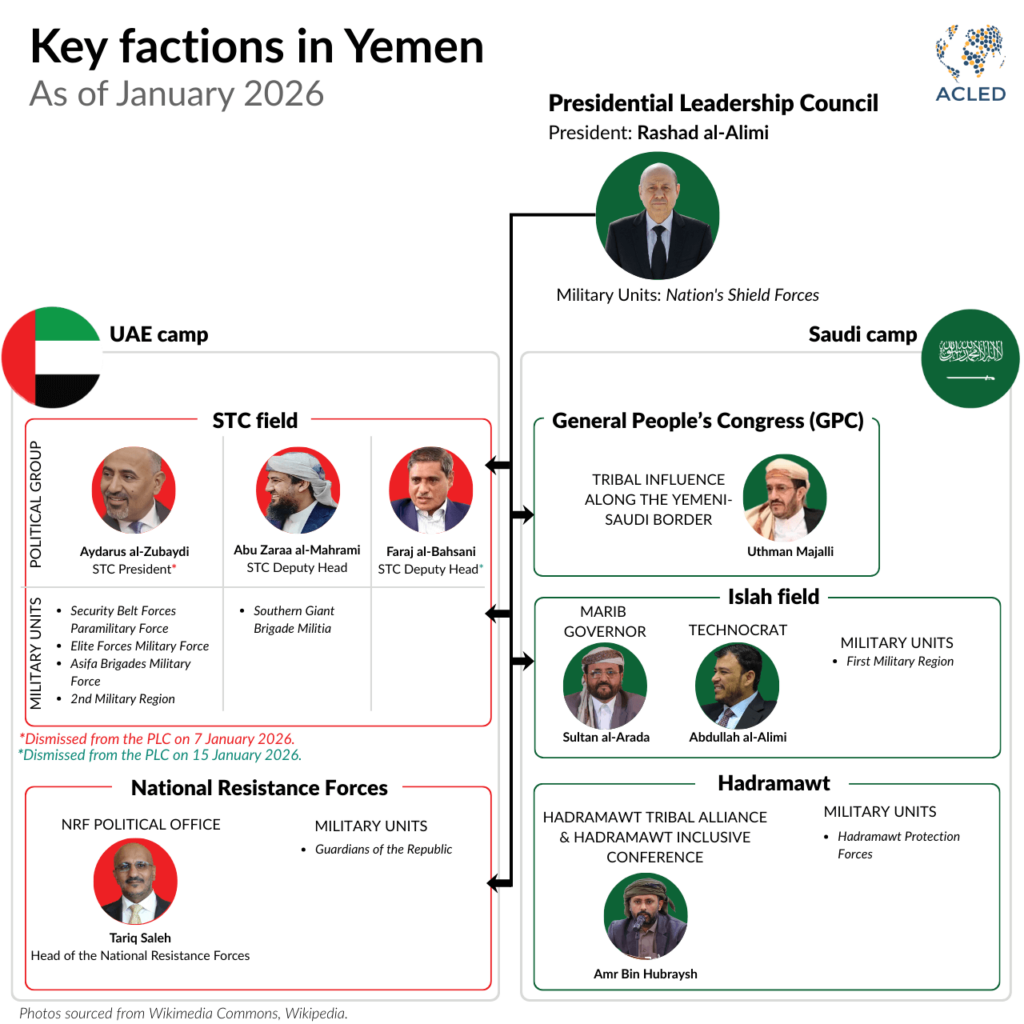

The crisis has occurred within the camp of Yemen’s Internationally Recognized Government (IRG), fueled by competing agendas pursued by Saudi Arabia and the UAE and their respective proxies. The bulk of the confrontations opposed military forces affiliated with the UAE-backed STC and a constellation of Saudi-backed actors, including tribal groups, the Islah party, and the NSF (see diagram below).

Who are the main players in the UAE-backed camp?

The STC is a southern secessionist political group led by Aydarus al-Zubaydi. On the eve of the crisis, it projected its influence across large swaths of southern Yemen, including its stronghold in al-Dali governorate, as well as Aden, Shabwa, Abyan, the coastal areas of Hadhramawt, and the island of Socotra. Politically, the STC had a consolidated position within state institutions, with several governors and cabinet ministers drawn from its ranks. Militarily, it relied on a network of UAE-backed forces, most notably the Security Belt Forces and Elite Forces.

Other key UAE-backed figures include Tariq Saleh, leader of the National Resistance Forces, who controls Yemen’s West Coast and advances a pro-unity agenda against the Houthis, and Abu Zaraa al-Mahrami, a Salafist leader, deputy head of the STC, and commander of the Southern Giants Brigades.

Overall, the UAE-backed camp was the dominant stakeholder within the PLC.5

Who are the main players in the Saudi-backed camp?

The Islah party is a pro-unity Islamist group that controls the powerful 1st Military Region in Marib province, along with areas in and around Taizz city. It is labelled a terrorist group by the STC, due to its connections with the Muslim Brotherhood. On the eve of the crisis, the 1st Military Region controlled the interior (Wadi) of Hadramawt, with its headquarters in Sayun.

Riyadh also backs several local groups in Hadramawt that uphold self-rule and oppose the STC’s secessionist approach, rejecting the primacy of the so-called “Southern Question” — an ensemble of southern Yemeni grievances over unaddressed political, economic, and social demands — and prioritizing local identity over a broader southern identity. These groups include the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance and Hadramawt Inclusive Conference, both led by the tribal shaykh Amr bin Hubraysh.

The NSF are military units funded and established by Saudi Arabia in 2023 to support the PLC, the executive body of Yemen’s IRG. They are led by Salafi commanders and conceived as a pro-unity force loyal to Riyadh, serving as a counterbalance to UAE-backed formations. On the eve of the crisis, they controlled parts of the interior of Hadramawt and al-Mahra.

What are the immediate political consequences of these territorial shifts?

The rapid Saudi advance left the STC isolated and weakened. On 7 January, al-Zubaydi deliberately avoided scheduled peace talks in Riyadh. His attempt to mobilize an armed insurgency in Yemen prompted his dismissal from the PLC and his referral to a penal court on charges of high treason.6 Concurrently, nearly the entire contingent of STC-affiliated government officials was dismissed from their positions. On 9 January, the STC delegation in Riyadh announced the dissolution of the secessionist body.7

Saudi Arabia appears to recognize that dissolving the STC created a political vacuum in the representation of southern constituencies and the Southern Question. Accordingly, it launched the Comprehensive Southern Dialogue Conference8 — an initiative supported by the STC delegation in Riyadh and attended by other major UAE-backed Yemeni forces9 — as part of a broader effort to broaden southern representation, reform the PLC, and stabilize southern Yemen.

Is this the end for the STC?

The situation in southern Yemen remains highly volatile. The STC appears significantly weakened, but not defeated. Several senior STC figures have rejected the move to disband the organization and continue to support Zubaydi’s leadership and his secessionist agenda.10 Meanwhile, STC offices inside Yemen remain operational,11 despite attempts by government authorities to shut them down.12 STC hardliners are likely to continue operating from abroad, while second-tier leaders may be absorbed into future southern organizations. Grassroots support is likely to remain rooted in southwestern Yemen, particularly in al-Dali and Aden.

On 10 January, a massive demonstration in Aden rallied in defense of the STC, calling for renewed attention to the southern cause and rejecting external pressures. This served as a stark reminder that a significant political space around the southern cause persists and continues to demand credible political answers.

What are the next steps for Saudi Arabia?

Riyadh is seeking to develop a unified political representation for southern Yemen. This effort is fraught with challenges. Southern politics are currently fragmented among a proliferation of groups with limited local representation. Any dialogue will need to identify credible actors and bridge key political divides — most notably between local self-rule claims and the pursuit of a shared southern identity.

In parallel, Saudi Arabia is likely to pursue PLC reform, as its eight-member structure — designed to balance military forces on the ground — has proved unwieldy and ineffective, hampering decision-making. The PLC is therefore expected to be reduced to a more streamlined leadership structure, centered on a president and one or two deputies.

Lastly, the collapse of most pro-STC forces opens a window for reform of the military and security apparatuses. In line with the 2019 Riyadh Agreement, President Rashad al-Alimi is likely to pursue the unification of command and control, integrating all forces under the Ministries of Defense and Interior.13 Yet factional loyalties and external backing remain major obstacles, particularly as Saleh and al-Mahrami continue to receive UAE support.

What’s the role of the UAE in Yemen’s future?

The role of the UAE remains unclear. Against a backdrop of regional realignment — where Abu Dhabi is increasingly seen as being close to Israel and distant from Riyadh14 — the UAE operates in relative isolation. In this context, the STC’s secessionist stance met strong regional and international pushback, with many actors — including Egypt, China, the European Union, and the United Nations — reaffirming support for Yemen’s unity.

Overall, Abu Dhabi has suffered a major setback, losing influence over the key port cities of Aden and al-Mukalla. Yet, the withdrawal from Socotra and Perim may represent a tactical de-escalation. Moreover, the UAE has historically relied on two powerful allies — Tariq Saleh and Abu Zaraa al-Mahrami — who retain influence over strategic areas along the west coast, maintain security in Aden, and continue to play a pivotal role on the frontlines against the Houthis. Both allies are politically closer to Riyadh’s pro-unity position, but they may ensure continued Emirati influence during the current phase.

What’s the Houthis’ reaction to the crisis?

The Houthis remained largely silent throughout the crisis, reiterating their long-standing view that both the UAE and Saudi Arabia are occupying forces in southern Yemen seeking to sow chaos through divide-and-rule politics.15 However, despite this claimed equidistance, the group is clearly more hostile toward the UAE and has strongly criticized Abu Dhabi’s implicit support for Israel’s recognition of Somaliland.16

A weakened role of the UAE in Yemen may facilitate negotiations between Riyadh and the Houthis and pave the way for a nationwide settlement, though several obstacles remain. First, trust between Riyadh and Sanaa has deteriorated following Houthi attacks in the Red Sea, creating the need for specific security guarantees. Second, the foreign terrorist organization designation of the Houthis may complicate the implementation of any agreement. Finally, a United States or Israeli military operation against Iran could trigger a new round of confrontations and further delay peace talks.

Can AQAP exploit the current crisis?

Since 2022, the STC has conducted counter-terrorism operations against al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) in the governorates of Abyan and Shabwa. While AQAP activity has largely remained low, the group has proved highly resilient, limiting the effectiveness of these operations and repeatedly forcing STC forces to re-clear the same areas. The last campaign took place in September 2025.

AQAP reportedly portrayed the STC’s pullback as a victory and is alleged by local sources to have looted arms depots left vacant by withdrawing forces17 and to have expanded into Hadramawt.18 The retreat of UAE-backed counter-terrorism units is likely to create openings for AQAP to regain lost positions in Abyan and Shabwa, while enabling a strategic recalibration of its targeting.