As fighting closes in, the fate of the lakeside city could reshape military strategy across the Kivus, reroute regional trade and alter Kinshasa’s political fortunes.

As fighting between the Congolese army coalition and the Rwanda-backed AFC/M23 rebels edges closer to Uvira, the strategically placed lakeside city has become the hinge on which, analysts warn, the next phase of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s war may turn.

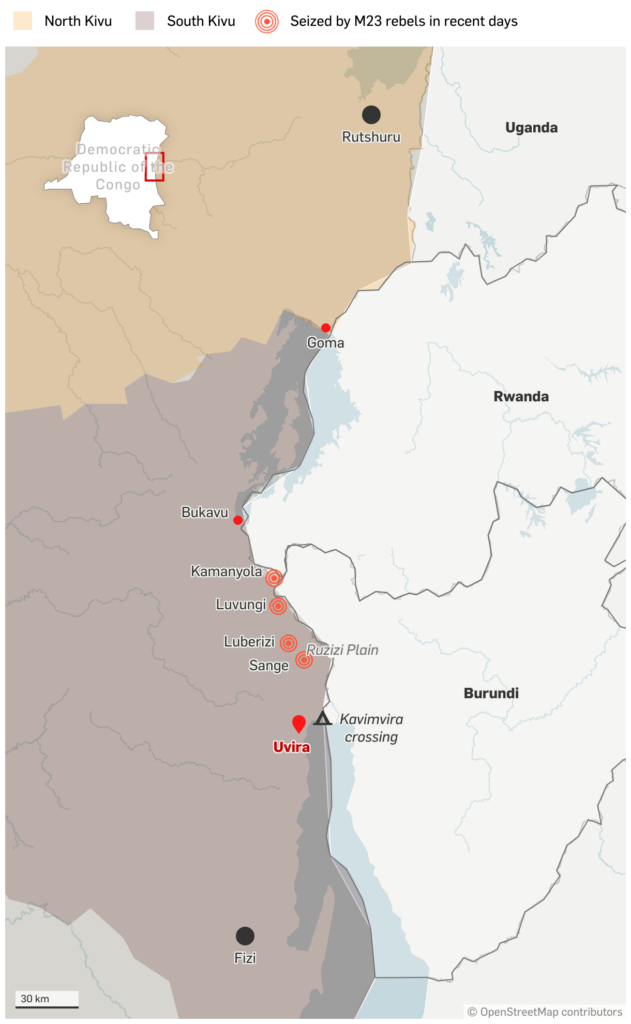

In recent days, the rebels have seized Kamanyola, Luvungi, Sange and Luberizi, pushing to within operational distance of Uvira, the government’s last major foothold in South Kivu after Bukavu’s fall in February.

For the city’s 700,000 residents, gunfire now echoes from the plateaus above, with tens of thousands fleeing toward Burundi or Kalemie as those who remain brace for a confrontation many fear is inevitable.

A city trapped by its own strategic geography

Uvira’s geography is both its strength and its vulnerability: it sits on a narrow strip of land squeezed between the towering plateaus to the west and Lake Tanganyika to the east.

This position, notes Jean Masemo, director general of the eastern DRC-based research organisation Initiative des Jacobins Éleveurs pour le Développement (IJED), makes the city an important hub not only for neighbouring Rwanda and Burundi but also for Tanzania and Zambia.

To the north lies the Ruzizi Plain, a 90km corridor that FARDC (DRC Armed Forces), Burundian forces and Wazalendo militias have turned into a defensive barrier, while to the south, a fragile road-and-lake axis to Fizi and Kalemie remains the city’s main lifeline for supplies and withdrawal.

Uvira is now “a city in freefall”, according to the security analysis group African Security Analysis (ASA).

In its latest intelligence report published on Tuesday, ASA warns that FARDC troops, allied militias and civilians “have descended into chaos amid internal clashes, desertions and a rapidly tightening rebel encirclement. The noose is closing from the Ruzizi Plain, the western highlands and the north–south axis”.

FARDC morale is collapsing, humanitarian agencies are withdrawing, and civilians are fleeing in multiple directions, the report says.

For Burundi, just across the Ruzizi River, the situation amounts to “its gravest national security threat in over a decade”.

What the fall of Uvira would ultimately mean

The capture of Uvira, South Kivu’s second-largest urban centre, will not be just another town changing hands on a crowded conflict map.

It will represent a structural shift in how power, territory, trade and leverage are distributed in eastern DRC and the wider Great Lakes region.

Militarily, Uvira is the last major node anchoring the Congolese government’s presence in South Kivu.

...living in a state of general psychosis without any tangible sense of hopeIts fall would complete a chain of losses that already includes Bukavu and a swathe of surrounding territory.

An eastern DRC scholar who requested anonymity for security reasons says control of the plateaus is decisive, noting that whoever holds the “heights above Uvira controls the approaches below”.

If M23 consolidates positions in localities such as Kashatu and pushes further along the ridgelines, the scholar warns, the city could be surrounded, with the Kavimvira crossing into Burundi as its only credible exit point.

“Should that corridor be cut, Uvira will be sealed off from land evacuation and resupply,” the scholar adds.

The M23’s capture of Luvungi and Kamanyola – both near the Burundian border and roughly 30km from Uvira – has complicated the diplomatic landscape.

Jervin Naidoo, a political analyst at Oxford Economics, says these gains weaken the foundations of the 4 December Donald Trump-backed peace deal signed between the DRC and Rwanda in Washington, as well as the ongoing Doha negotiations between Kinshasa and M23.

“The advances suggest that any agreements reached may only offer short-term stability without addressing the underlying drivers of the conflict,” he says.

Losing key battles

Naidoo adds that Uvira, still under government control, has become a key flashpoint.

Its loss, alongside M23’s hold over Bukavu and Goma, would signal that the army is losing key battles and allow the rebels to consolidate a broad corridor of influence across the east.

“This would substantially increase political risk,” he says, weakening President Félix Tshisekedi’s authority, reinforcing perceptions of persistent state fragility and raising uncertainty among investors, regional actors and international partners watching the DRC’s stability.

“With control over key towns and the revenue they generate, M23 has little incentive to compromise, forcing the DRC government, and President Tshisekedi in particular, to negotiate from a position of weakness,” Naidoo tells The Africa Report.

Kigali’s allies control Goma, Bukavu and Uvira, while Kinshasa clings to less strategic urban centres further inlandThis dynamic, he adds, undermines Tshisekedi’s standing domestically and will embolden rivals, including figures like former president Joseph Kabila and the AFC, who are “eager to exploit” any perception of fragility to challenge his authority.

ASA says Uvira now faces an “imminent” takeover by the M23 alliance, pointing to the rebels’ “sweeping and unprecedented” gains in Goma and Bukavu.

“Should Uvira fall, it would mark the near-total loss of government control across the Kivus,” the report warns, “triggering consequences that will reshape regional security”.

Regional power play: Burundi, Rwanda and Lake Tanganyika

Uvira’s fall will also reshape regional security calculations. The town sits almost opposite Bujumbura across Lake Tanganyika.

For Burundi, M23’s arrival on the lakeshore will mean a hostile force within eyesight of its economic capital.

Burundi has escalated by firing artillery into Kamanyola from its own territory and pushing thousands of troops into Congo to block the rebel advance.

Analysts say the loss of Uvira despite this effort will be a psychological and strategic blow to Bujumbura, undercutting the narrative that Burundian intervention could halt M23’s momentum.

It could push Burundi into deeper, riskier engagement or conversely into a more defensive posture focused on guarding its own borders, leaving FARDC more exposed.

For Rwanda, Uvira will represent an expanded depth of influence along the lakefront and another bargaining chip in any future talks.

“The optics will be stark,” the DRC scholar argues.

“Kigali’s allies control Goma, Bukavu and Uvira, while Kinshasa clings to less strategic urban centres further inland.

“That imbalance will feed into regional diplomacy, from Washington to Doha, and intensify debates over whether the balance of power in the Great Lakes is tilting decisively away from Kinshasa.”

Neighbouring Tanzania and Zambia, which rely on Lake Tanganyika and associated trade corridors, will also be forced to recalibrate.

An M23 presence in Uvira will inevitably pull the conflict’s security risks closer to its own logistical arteries.

Economic shock

Uvira is one of the key commercial lungs of South Kivu.

It is a port, a road junction and a customs point all at once, connecting Bukavu to Burundi and Tanzania and helps channel goods, from food, fuel and cement to industrial inputs, across the lake and into the interior.

Should Uvira fall, it would mark the near-total loss of government control across the KivusMichael de Kock, an economist at Oxford Economics, notes intensified conflict around Uvira would likely disrupt formal export routes for 3Ts (tin, tungsten and tantalum) and gold, adding however, that global supply chains will more likely experience disruption to traceability rather than total supply shortfalls.

“M23’s advances across Uvira territory and South Kivu’s provincial capital Bukavu have already stifled certified mineral trade through official channels, meaning minerals will increasingly flow through informal smuggling networks via Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda, a pattern already well-documented, though the governments of these countries tend to deny these allegations of these smuggling networks,” de Kock tells The Africa Report.

For regional trade balances, he adds, this dynamic will further inflate official mineral export revenues for some of the DRC’s neighbouring countries at Kinshasa’s expense.

Humanitarian freefall

There are also growing concerns that the fall of Uvira will deepen an already dire humanitarian crisis.

The town has long served as a refuge for people fleeing violence in the highlands, the Ruzizi Plain and other parts of South Kivu.

Médecins Sans Frontières reported that by late May more than a quarter of a million people had been displaced towards Uvira, with many more on the move since.

Should the rebels enter the city, a second, even more chaotic wave of displacement will follow across Lake Tanganyika in overcrowded boats, up the Ruzizi River or into already overstretched urban centres like Kalemie.

With nearly six million people displaced across eastern DRC and 27 million facing hunger, the region has little capacity to absorb another shock of that scale.

Jean Masemo describes a population already “living in a state of general psychosis without any tangible sense of hope”.