Persistent resistance to power sharing between Somalia’s federal and state governments has brought al Shabaab to the precipice of taking Mogadishu and escalating the threat from international jihadists.

Highlights

Al Shabaab poses a serious threat of taking Mogadishu—largely due to a breakdown in political cooperation between federal and state authorities.

Such an outcome would empower a militant Islamist alliance with global ties, profoundly reshaping the international fight against terrorist groups.

Somalia is becoming an increasingly regionalized conflict with Gulf states supporting rival Somali actors and ambitions.

Pulling Somalia back from the abyss may still be possible but would require fundamental political and security reforms and a reinvigorated African Union peacekeeping force.As al Shabaab embarked on a sweeping offensive across much of central Somalia in April 2025, diplomats in Somalia’s seaside capital began mulling over a disconcerting hypothetical. Would the fall of Mogadishu resemble more the Taliban conquest of Kabul or Hay’at Tahrir al Shams’ domination of Damascus? Al Shabaab had seized a succession of strategic towns from the Somali National Army with little apparent difficulty. By July, the militants had largely encircled the capital, advancing to less than 50 kilometers from Mogadishu and setting up checkpoints on its outskirts. Many foreign embassies in the city withdrew nonessential staff to neighboring Kenya. Then, inexplicably, the advance paused, leaving Somalia’s beleaguered federal government to claim victory while less sanguine observers wondered when the offensive might resume.

Somalia is embroiled in a deepening crisis involving an ascendant jihadist insurgency, a faltering peace support operation, domestic political polarization, and regional geopolitical competition. The federal government’s de facto sphere of control is confined to Mogadishu and a few satellite towns: essentially a metropolis with a diplomatic corps and a demoralized, ineffectual army. Absent a dramatic change in direction, likely near-term scenarios include collapse of the federal government and an al Shabaab takeover of the national capital, with profound consequences for regional stability and security.

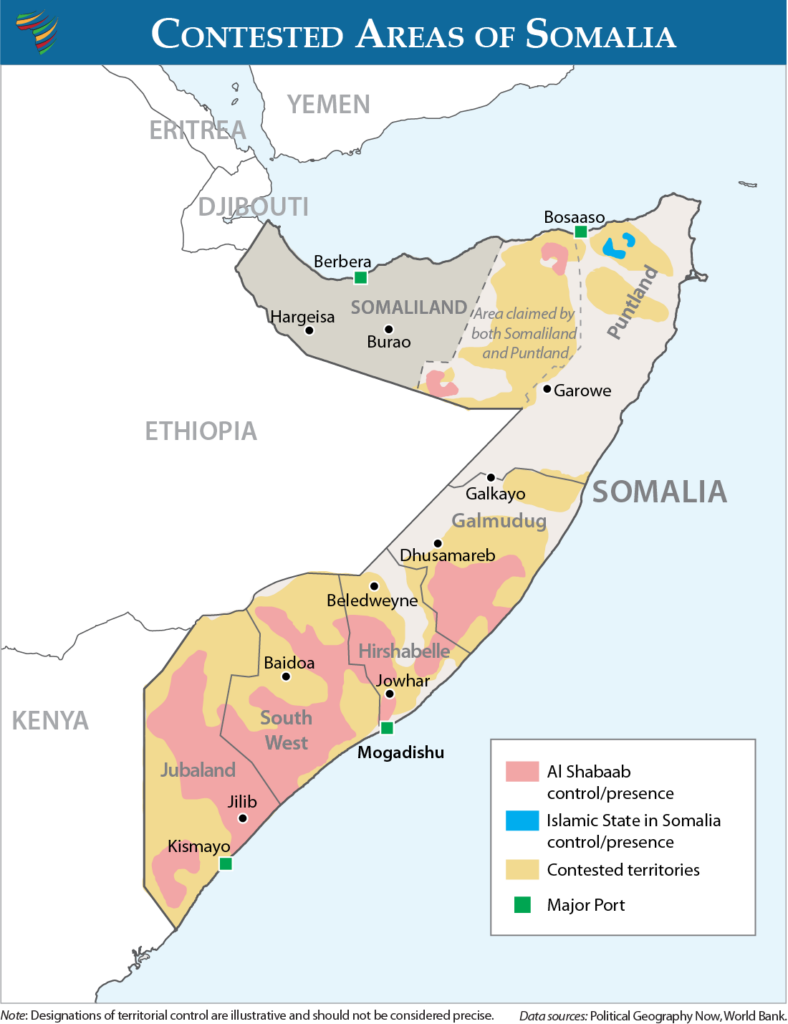

Al Shabaab’s strength has always been a reflection of the Somali government’s weakness.An insurgency waged by Harakaat al Shabaab al-Mujaahidiin (al Shabaab), an al Qaeda-affiliated terrorist organization, has been raging for nearly two decades. The group now controls roughly 30 percent of Somalia’s territory—far more than the fragile federal government in Mogadishu. In 2023, a short-lived government offensive, supported by U.S. special forces, succeeded in wresting large swaths of central Somalia away from the militants. But progress tapered off after a few months, and al Shabaab has since recovered almost all of that lost ground. The group is currently building up forces around Mogadishu and has stepped up attacks inside the city. In October 2025, an al Shabaab suicide squad stormed the Mogadishu branch of the national intelligence service, NISA, destroying valuable intelligence and releasing dozens of prisoners—just a stone’s throw from the presidential palace (Villa Somalia).

Al Shabaab’s strength, however, has always been a reflection of the Somali government’s weakness. Despite more than two decades of investment and billions of dollars in training and equipment, the Somali National Army (SNA) is still incapable of sustained clearing and holding operations. In an address before Parliament in November 2025, Chief of Defense Forces General Odowaa Yusuf Raage disclosed that between 10,000 and 15,000 troops had been killed or wounded in action over the past 3 years. The force suffers from a host of troubles, including poor leadership, corruption, uneven training standards, and a reliance on clans deemed loyal to a sitting president rather than being a force having a genuinely national character. This has left the federal government of Somalia heavily reliant on the African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) for security. Meanwhile, Mogadishu’s political interference in the mission has left AUSSOM under strength, without a unified chain of command, and hemorrhaging donor support, threatening the reduction or termination of the mission.

These challenges are symptoms of much deeper problems: the unravelling of Somalia’s federal political settlement and cyclical constitutional and electoral crises. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s recent attempts to amend the constitution, impose a new electoral system, and redraw the federal map are widely viewed as maneuvers to stay in power beyond the end of his term in May 2026,1 with the effect of spinning Somalia even faster toward fragmentation.2 As a result, Somalia’s political class is dangerously polarized and unable to forge a united front against their common enemy, al Shabaab.

Al Shabaab, for its part, seems content to watch and wait while its enemies quarrel, international partners cut back on security and development assistance, and AUSSOM contemplates withdrawal. As a growing number of international partners have begun quietly exploring prospects for a negotiated peace with the militants, absent some deus ex machina to salvage Somalia’s federal system, al Shabaab’s seizure of Mogadishu may already be simply a matter of time—whether through military action or negotiations. If so, a new cycle of armed conflict between a further empowered al Shabaab in control of Mogadishu and its 4 million inhabitants, and their sworn enemies in other parts of the country will be all but inevitable. Neighboring countries would similarly face the heightened prospect of renewed terrorist attacks across their borders. The time for hopeful half-measures is past. Only urgent, decisive, and concerted intervention can prevent Somalia from becoming a jihadist state.

Contested State Formation

Almost 35 years since the collapse of the dictatorial government of Siad Barre in 1991, Somalia’s leaders are unanimous in their commitment to a unified nation-state (with the exception of Somaliland, which declared independence in 1991 and has functioned as a separate state ever since). Aside from that, they agree on very little else. The essential elements of a comprehensive governing charter continue to elude them: a definitive and universally recognized constitution, stable power-sharing arrangements, and a unified electoral system. Instead, the country remains fractured and fissile, ensnared in a perpetual power struggle between the country’s fragile federal government and powerful regional administrations.

A Dark Legacy of Concentrated Power

As one of the world’s least developed countries, Somalia has relied on foreign financial and military support for its survival as a state. A 1957 assessment by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) projected that the new state would require financial assistance for at least 20 years post-independence. Western governments shouldered the burden for almost a decade after the Somali Republic was established in 1960, but a 1969 military coup brought Siad Barre to power with the blessing of a new benefactor: the Soviet Union (USSR). The military payroll alone quickly escalated to over a quarter of the national budget, with hardware such as tanks and aircraft donated by the USSR and Eastern Bloc allies. External debt nevertheless soared as well, exceeding $1.7 billion—almost twice the value of GDP—immediately prior to state collapse in 1990.3

This combination of Soviet patronage and rapacious borrowing enabled Barre to rule Somalia for almost a decade as a highly centralized and militarized garrison state. But when Somalia staged a disastrous invasion of Ethiopia in 1977-8, the USSR decided to back Addis Ababa instead. Barre pivoted to a much less obliging United States and its Western allies. Reeling from its catastrophic military defeat and the loss of virtually unconditional Soviet support, the Barre regime struggled to maintain its authority. Armed opposition first emerged in 1978, and rebel groups proliferated through the 1980s, harrying the regime on several fronts. With the suspension of American military support in 1989 and the fall of the Berlin Wall the same year, Barre was on his own. Without a foreign benefactor to pay the bills, he was no longer able to hold the country together.

Throughout the 1990s, an array of warlords with clan militias jostled for supremacy—some of them even adopting the title of “president.” But the Somali Republic had effectively disintegrated into a patchwork of clan-based, local authorities managing parts of the territory, with the rest consigned to a combination of pre-colonial, Somali governance traditions and predatory militia factions. As the symbolic seat of national power, Mogadishu remained particularly lawless, since its resident warlords and their supporters believed that control of the capital was tantamount to national leadership, and therefore worth fighting for. But that was the one thing that most other Somalis could agree on: never again should so much power be vested in a national government such that despotism or dictatorship could reemerge.

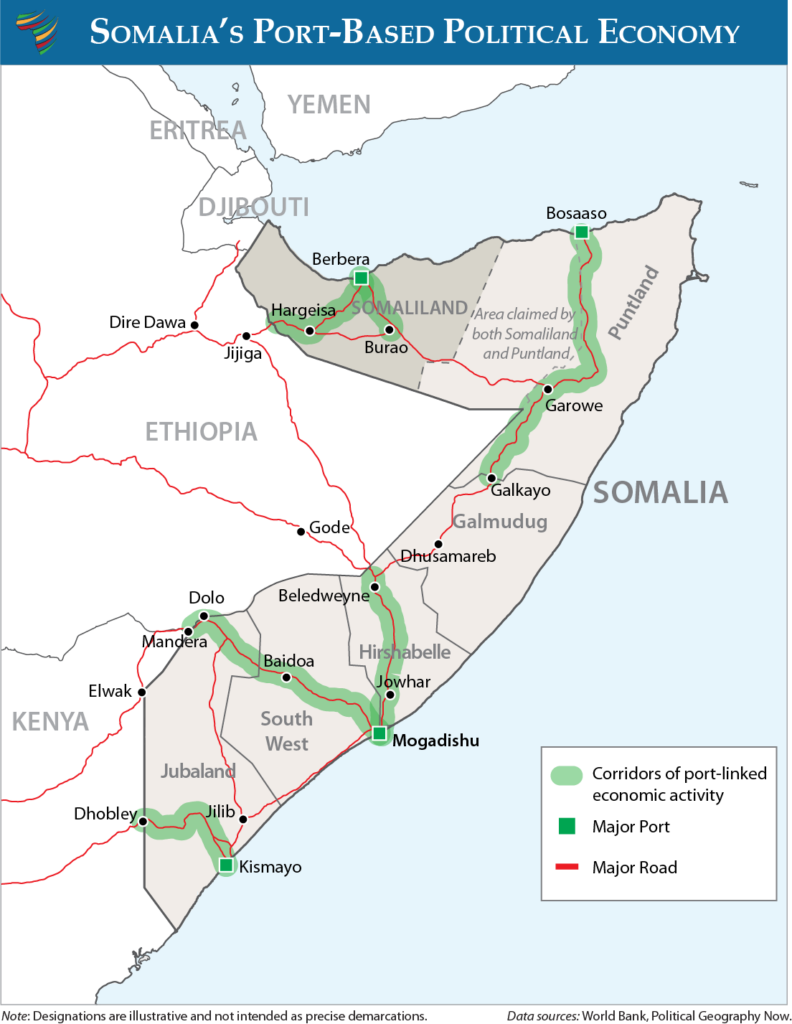

In the absence of a functioning national government, power in Somalia became not just decentralized but “uncentralized,”4 with its political economy coalescing around four deepwater ports—Berbera, Bosaaso, Kismayo, and Mogadishu. Control of these lucrative assets, as well as lesser economic infrastructure such as airports and roads, came to shape the dynamics of Somalia’s protracted civil war. By the late 1990s, it had become widely accepted that a decentralized process of state reconstruction, starting with these “port economies” and their corresponding regional authorities, offered the most logical path forward in Somalia’s highly dispersed and complex societal structures. By 1999, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), comprising the member states of the Horn of Africa, had coalesced around a bottom-up, proto-federal paradigm known at the time as the “building blocks” approach, rather than the imposition of a national government in Mogadishu.

Following several false starts, Somalia’s parliament adopted a provisional constitution in 2012 that laid the foundation for a parliamentary, federal republic. According to the Provisional Constitution, the Council of Ministers, chaired by the Prime Minister, is designated as “the highest executive authority of the Federal Government,” with the President serving in an essentially ceremonial role.5 The Provisional Constitution stipulates two levels of authority: the Federal Government (FGS) and Federal Member States (FMS). Not coincidentally, the three most powerful States—Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland—administer the port economies of Berbera, Bosaaso, and Kismayo, respectively. The fourth port, Mogadishu, sustains both the local Banaadir administration and the FGS itself, which controls 85 percent of Mogadishu’s port revenues.

Today, each of these port economies generates between $100 and $400 million in revenue per year, sustaining regional authorities and their security establishments. In the absence of a comprehensive political settlement, relations between these administrations are characterized by an inevitable degree of competition. None of them—including the putative “federal government” in Mogadishu—is strong enough to impose its will on the others. Meanwhile, Somalia’s remaining FMS—South West, Hirshabelle, and Galmudug—all lack deepwater ports and are largely dependent on the authorities in Mogadishu for revenue. This imbalance is a source of deep political friction within the incipient federation. The wealthier, more powerful FMS assert more autonomy from Mogadishu, while the weaker members generally acquiesce to the FGS’s wishes.

Creating and maintaining functional federal structures is a challenging undertaking anywhere, since they explicitly require power sharing between different levels of government (and often between different parties, ethnicities, and interests). The benefits are that they bring government decision-making closer to citizens, allow for more contextualization within diverse societies, and represent another check on unrestrained executive authority. But in Somalia’s case, the challenges of building a functioning federation have been amplified by the vagaries and ambiguities of the Provisional Constitution—a deeply flawed document. Apart from designating authorities for foreign affairs, national defense, citizenship and immigration, and monetary policy to Mogadishu, the text is silent on the division of powers and resources between federal and state authorities. Nearly all else, from national security to fiscal federalism, natural resource management, and social services, “shall be negotiated and agreed upon by the Federal Government and the Federal Member States.”6

Instead of negotiating, however, successive federal presidents have sought to concentrate power in their own hands, both by unilaterally arrogating authorities to the central government and by assuming executive authority that is constitutionally vested in the Council of Ministers. This trajectory has reached its zenith during the second term of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud (HSM), who appears determined to establish a presidential, unitary system of government in all but name.7 Two of Somalia’s five FMS, Puntland and Jubaland, have reacted by suspending relations with Mogadishu and withdrawing their recognition of federal authority. The power struggle has plunged the federation into political chaos and a constitutional void, paralyzing the war effort against al Shabaab.

Instead of negotiating, successive federal presidents have sought to concentrate power in their own hands.The FGS contends that Puntland and Jubaland are spoilers, whose demands for autonomy are unwarranted and unreasonable. From a constitutional perspective, however, the federal government does not have the authority to decide which powers should reside with the FMS. It is empowered only to negotiate. Villa Somalia’s attempt to position itself as the arbiter of powers and resources within the federation is not enabled by constitutional authority but rather by its externally conferred sovereign status and access to foreign assistance. Universal international recognition of the FGS in 2012, despite its provisional legal status, unlocked unprecedented access to donor support. Since then, donor funding for Somalia has risen to between $5 and 7 billion per year, of which roughly one-third is earmarked for security and approximately $1 billion is designated as direct “on-budget” financial support for the FGS. In fiscal year 2025-2026, this constitutes roughly 70 percent of the federal budget. Without this financial lifeline, the FGS would struggle to administer Mogadishu, let alone dictate terms to the FMS.

Another source of tension in the negotiations over the federal structure involves a new “one person one vote” electoral system promising universal suffrage. Villa Somalia envisages a “three tier” electoral process, with local elections followed by state elections and, eventually, elections for a new federal parliament, which will in turn elect the next president. Some international partners have welcomed this intention as a critical step toward democracy. However, others are concerned that voting could only take place securely in Mogadishu and a handful of other towns in southern Somalia where the FGS holds sway. The proposed electoral model would enable voters from these urban enclaves to elect the entire parliament. The effect would be that the vast majority of new federal members of parliament (MPs) would represent parts of the country where no election takes place—such as Puntland and Jubaland—a result that would dangerously magnify the regional and clan cleavages that have rendered Somalia’s crisis so intractable.

Since it is highly unlikely to complete all the steps required for such an electoral process by May 2026, Villa Somalia is quietly preparing the ground for an unconstitutional term extension for HSM of at least 2 more years.8 Such a move would likely be strongly rejected by Puntland and Jubaland as well as the National Salvation Forum—an opposition political coalition based in Mogadishu. The risk of subsequent violent uprisings is very real. In 2021, national opposition leaders—HSM among them—mobilized militias in the capital city to block then President Mohamed Abdillahi Farmaajo from seeking a term extension under near-identical circumstances. A similar standoff would likely be triggered again. Violent clashes in the streets of Mogadishu would serve only to delegitimize the FGS even further, while handing another propaganda victory to al Shabaab.

Toward an Islamist State

While the path to constructing a functional federal system in Somalia remains unclear, the prospect of the country becoming an illiberal, Islamist state is growing increasingly likely. Somalia’s 1960 Constitution established Islam as the state religion but confined the application of Shari’a law to the personal status of Muslims. In all other respects, Somalia possessed the characteristics of a secular state. The 2012 Provisional Constitution, however, is explicitly “based on the foundations of the Holy Quran and the Sunna of our prophet Mohamed (PBUH) and protects the higher objectives of Shari’ah and social justice.”9 No law can be enacted that “is not compliant with the general principles and objectives of Shari’ah.”10

Hopeful portrayals of al Shabaab as a reasonable political actor and potential partner in Somalia’s governance are unfounded and untested.The unequivocally religious character of the new constitutional text is symptomatic of the steady rise of Somali Islamist movements following the collapse of the Barre regime in 1991. Since 2009, when President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed ushered in his Aala Sheekh faction of the Muslim Brotherhood into Villa Somalia, political Islamists have enjoyed uninterrupted alternations of power in Mogadishu. HSM succeeded Sheikh Sharif in 2012 as the candidate of the Damul Jadiid (“New Blood”) party, another faction of the Muslim Brotherhood with ties to Qatar, Türkiye, and Kuwait. In 2017, HSM handed over power to Farmaajo and the powerful Salafi sect, al Ictisaam b’il Kitaab wa Sunna (al I’tisaam)—a secretive offshoot of Somalia’s first jihadist organization: al Itixaad al Islaami (al Itihaad).

Established in 1983, al Itihaad fought to establish an Islamic “emirate” in Somalia in the early 1990s but was crushed by the Ethiopian military in 1997 and split into two factions: al Shabaab and al I’tisaam. The two factions are ideological twins—two faces of the same Salafi-jihadist coin—but political rivals who pursue political power through different means. Whereas al Shabaab seeks to rule through force of arms, al I’tisaam proselytizes through an extensive network of Salafi mosques, madrassas, markazes, schools, and universities, while its vast empire of businesses and charities wages socioeconomic “jihad.” Today, Somalia’s financial services, telecommunications, and petroleum products—to name just a few—are dominated by enterprises affiliated with al I’tisaam. During Farmaajo’s administration, al I’tisaam tasted unprecedented proximity to power as the undeclared ruling party. Any prospects for reconciliation with al Shabaab, however, did not materialize. When HSM was reelected in 2022, al I’tisaam was shunted aside.

During HSM’s second term, Damul Jadiid and Al I’tisaam have settled into a tetchy modus vivendi, mediated by their common patron, Qatar. Damul Jadiid dominates the executive branch while a prominent al I’tisaam cleric, Sheikh Bashir Salaad, chairs the national Ulema Council. Damul Jadiid is routinely depicted as more “progressive” than other Somali Islamist groups, but the conservatism and religious bigotry of some senior officials are a matter of public record. Villa Somalia’s controversial constitutional amendments, moreover, are suffused with Salafi jurisprudence proffered by al I’tisaam legal scholars, including provisions that contravene Somalia’s human rights obligations as a member of the African Union (AU) and United Nations (UN).11

If Somalia does succeed in holding some kind of election in 2026, any serious presidential contender will likely require the backing of one of these Islamist groups. And if the winner is not al I’tisaam’s chosen candidate, he will likely need to strike a deal with the Salafists in order to govern effectively. That will reinforce pressures toward greater centralization of power in Mogadishu and an increasingly pervasive influence of Salafi dogma in the guise of religious authenticity. It will therefore also probably engender even deeper tensions between the federal center and its peripheries, which have yet to fall as deeply under Salafi influence.

All major Somali Islamist movements aspire to a centralized, unitary Somali state, but most have struggled to gain traction beyond Mogadishu and the central regions. Only al I’tisaam has managed to sway politics in Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland—typically by suborning politicians and subverting their governments in order to gradually dilute their autonomy and compel their incremental integration within a central Islamist authority. However, as recent history attests, when Islamist sects take power in Mogadishu, and the federal government’s formidable instruments of compulsion—diplomatic isolation, economic pressure, lawfare, and even warfare—are harnessed with the aim of dismantling federalism, the result is even deeper polarization, militarization, and armed conflict.

Regional Geopolitics are Amplifying Pressures

Geopolitics across the Horn of Africa are further aggravating Somalia’s internal fissures. Regional dynamics are increasingly shaped by the interests of rising middle powers, especially the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye. Somalia is just one of several theatres in which their strategic competition, ideological dissonance, and unstable coalition diplomacy are playing out.

The rise of Somalia’s Islamist movements represents one key axis of middle power rivalry. HSM’s closest allies are Qatar and Türkiye—relationships anchored in ideological affinity. Somalia’s Damul Jadiid and Türkiye’s Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) are both aligned with the Muslim Brotherhood, whose foremost global patron is widely acknowledged to be Doha. But Qatar also maintains discreet relationships with al I’tisaam and al Shabaab, including financial support for social services and humanitarian assistance in areas controlled by the militants, ostensibly to cultivate conditions for negotiations to end the conflict. Doha’s persistent promotion of a political dialogue between the FGS and al Shabaab, with a view to some kind of power sharing arrangement, is anathema to Somalia’s closest African neighbors (Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda) and many Western partners. Even al Shabaab seems unenthusiastic about the prospect of talks. But Qatar appears to believe that if al Shabaab were to renounce its affiliation with al Qaeda and rescind any territorial claims against neighboring countries, international reservations about the group could be overcome. And Doha’s unswerving advocacy to this effect suggests that the wealthy Gulf emirate is less invested in the success of any particular Somali leader than in realizing a long-term vision for Somalia’s future Islamist governance—with al Shabaab potentially as a major stakeholder.

“Most [Somali Islamist movements] have struggled to gain traction beyond Mogadishu and the central regions.”Beyond ideological ties, Türkiye’s interest in Somalia is both strategic and economic. Since President Recep Erdoğan (then Prime Minister) first visited Mogadishu in 2011, Ankara has enormously expanded its commercial, military, and humanitarian investments in Somalia (totaling roughly $220 million).12 Turkish NGOs have built hospitals, clinics, and schools across the capital. Turkish enterprises have been awarded long-term contracts to manage Mogadishu’s port and international airport, as well as infrastructure projects like roads and government offices—some of which are reportedly funded by Qatar (which also has more than $200 million of investments in Somalia). The TURKSOM military base and training center in Mogadishu is Türkiye’s largest in Africa and has trained thousands of soldiers for the SNA’s Gorgor advanced infantry battalions and the Haram’ad—a special paramilitary police unit. In early 2024, Ankara signed two ambitious agreements with Mogadishu: a comprehensive maritime and defense agreement and an oil and gas cooperation deal—both on highly favorable terms. Türkiye has also announced plans to build a major space launch facility and ballistic missile testing base on Somalia’s Indian Ocean coastline. Like Qatar, such large-scale investments are indicative of a long-term Turkish commitment to Somalia, regardless of who occupies the presidency.

While Qatar and Türkiye promote a strong, unitary Somali state under Islamist leadership, the UAE sits squarely on the opposite side of the equation. Abu Dhabi generally abhors Islamist movements and is sympathetic to decentralized, federal systems of governance. The UAE has therefore cultivated close ties with Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland, providing them with limited financial and security assistance, while maintaining prickly, but cordial, relations with Mogadishu—including payment of salaries for Emirati-trained military police units around the capital. Estimates are that the UAE supports $600 million in nonmilitary investment in Somalia—much of which is in Puntland. Emirati forces have established bases at Berbera airport (Somaliland) and Bosaaso airport (Puntland)—the latter serving as a logistics and transit hub for UAE military operations across the wider region.13 Emirati DP World has been awarded contracts to manage the ports of Berbera and Bosaaso, including major expansions of both facilities—strategically flexing the UAE’s considerable economic muscle.

More pragmatic, inclusive leadership from Villa Somalia, aimed at reunifying the country’s fraying federation and addressing Somaliland’s aspirations through meaningful dialogue, would go a long way toward harmonizing regional powers behind these same goals.In this regard, Emirati strategic objectives dovetail with those of Ethiopia and Kenya, whose vital security interests involve political and security cooperation with Somaliland, Puntland, and Jubaland. Conversely, as part of its rivalries with these three entities, Villa Somalia has turned to Egypt and the military authorities in Sudan for support, with both governments providing training for Somali intelligence officers and Cairo preparing to deploy a contingent of troops to Somalia with AUSSOM. As a result, Somalia is becoming increasingly entangled in a regional conflict vortex that, broadly speaking, pits Egypt, Eritrea, Sudan, Qatar, and Türkiye against Ethiopia, Kenya, and the UAE. For now, at least, external interference is more a symptom of Somalia’s internal disarray than its cause. More pragmatic, inclusive leadership from Villa Somalia, aimed at reunifying the country’s fraying federation and addressing Somaliland’s aspirations through meaningful dialogue, would go a long way toward harmonizing regional powers behind these same goals.

Somaliland

The question of Somaliland remains especially contentious within this context of regional geopolitics. In May 1991, soon after the fall of Siad Barre, the territory announced the dissolution of its messy 1960 union with Italian Somalia and reclaimed the sovereignty it had briefly enjoyed upon gaining independence from the United Kingdom. Somaliland has functioned as a de facto state ever since, with its own constitution, democratically elected government, security forces, currency, and passports—almost entirely without the benefit of bilateral donor support. Despite its lack of international recognition, Somaliland’s de facto independence from Somalia already exceeds the brief period during which the two states were united, meaning that the majority of Somalilanders—close to 75 percent—have no memory of a united Somali Republic. Among those old enough to remember, most suffered marginalization, brutal repression, and a “near genocidal” military campaign at the hands of the Somali government,14 leaving only a small, but vocal, minority of the population interested in any form of reunification with Mogadishu.

Somaliland also conducts an independent foreign policy, engaging in diplomatic relations with a growing number of foreign governments. Mogadishu and its allies reject Somaliland’s claim to independent statehood. However, after more than a decade of fruitless dialogue and 12 rounds of talks—in which Mogadishu has reneged on commitments it made—Hargeisa appears to have given up on any prospect of an “amicable divorce” from Somalia. Ethiopia is Somaliland’s largest neighbor and closest international partner with respect to security cooperation, trade, and exchange programs. The UAE also provides security assistance and has invested more than $500 million in upgrading the port and trade corridor between Berbera and the Ethiopian border. Somaliland’s close relations with Taiwan have also attracted the ire of Beijing, which has adopted a more explicitly “One Somalia, One China” policy and stepped up its relations with the FGS.

Ethiopia and Somaliland’s Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in January 2024, which proposed Ethiopia’s leasing 20 kilometers of Somaliland coastline for a naval base in exchange for recognition of Somaliland, dramatically boosted Somaliland’s geopolitical profile and provoked a bitter backlash from Mogadishu and its allies. Ethiopia subsequently paused implementation of the MOU. However, renewed American interest in Somaliland has ensured that the issue remains very much alive.

Somaliland, Puntland, and to a lesser extent some other FMS administrations, have proven that they are capable of providing not only peace and security, but also economic opportunities and personal freedoms that al Shabaab would never countenance.Opponents of Somaliland’s recognition argue that it would embolden separatist groups elsewhere in Africa, further destabilize Somalia, and aggravate the threat from al Shabaab. Proponents cite the unique strength of Somaliland’s legal case for independence; its relative peace, stability, and democratic credentials; and its Western-leaning foreign policy. Recognition, they argue, would enable Somaliland to engage in normal trade and commerce, and to become a meaningful partner in collective security and regional development. An AU fact finding mission in 2005 generally concurred with these arguments: Somaliland’s case for recognition, it concluded, is “historically unique and self-justified in African political history….[and]….should not be linked to the notion of ‘opening a Pandora’s box.’”15 Lack of recognition, on the other hand, “ties the hands of the authorities and people of Somaliland as they cannot effectively and sustainably transact with the outside to pursue the reconstruction and development goals.”16

In principle, Somaliland’s sovereign status should be determined by its intrinsic legal, moral, and political merits, and not only as a function of Somalia’s dysfunction. Nonetheless, Somaliland’s aspirations have long been subject to Mogadishu’s de facto veto—regardless of whether a viable Somali government existed or not. If the situation in southern Somalia does indeed deteriorate further toward either state collapse or an al Shabaab takeover, a growing number of countries seem prepared to reexamine Somaliland’s case for statehood on its own terms.

AUSSOM

Regardless of such a kaleidoscope of domestic and geopolitical dynamics, Somalia’s immediate fortunes hinge largely on the fate of the African Union Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). After nearly two decades in Somalia, donor fatigue and financial uncertainty over AUSSOM’s future may necessitate a drawdown, or even full withdrawal of the mission. The United States objects to the use of a new United Nations mechanism that would authorize the use of core UN funds for AUSSOM.17 Meanwhile, other traditional donors, including the European Union and United Kingdom, are unwilling to meet the shortfall on their own. As a result, the mission’s capabilities are certain to degrade and it may have to be reconfigured as little more than a guard force for Mogadishu’s port, airport, and foreign diplomatic “green zone.” Absent a new, bilateral military deployment by one of Somalia’s close allies, the FGS’s prospects of survival beyond that point would dramatically recede.

The AU’s protracted mission in Somalia has been widely maligned for its duration, cost, and failure to stabilize the country. But much of this criticism is undeserved. Between 2007 and 2011, AU troops battled street by street to liberate Mogadishu from al Shabaab, suffering grievous casualties in the process. In 2012, AMISOM regained control of the port of Kismayo, which had been a major source of revenue for al Shabaab. By 2016, the mission had achieved most of its primary objectives by securing the capital city and most other major towns across southern Somalia. For more than a decade, the presence of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) underpinned the freedom of Somali political leaders to deliberate the future of their country, build civic institutions, and generate sufficient Somali military and police forces to assume responsibility for national security.

A comprehensive plan for Somalia’s security and stability was adopted in May 2017 at a conference in London attended by representatives of the FGS, FMS, and international partners. The ensuing Security Pact, which was the culmination of almost a full year of negotiations between the FGS and FMS, mandated a federated National Security Architecture (NSA) to be in place by the end of 2017.18 Primary responsibility for the kinds of counterinsurgency and counterterrorism operations required to defeat al Shabaab was assigned to some 32,000 police officers, including heavily armed paramilitaries, distributed between the federal and state governments. An 18,000-strong SNA could provide higher echelon support as required. The transition from AMISOM to Somali security forces would begin in 2018.

The Farmaajo administration (2017-2022) quietly shelved the Security Pact before the ink was dry. The new FGS had no intention of seeing the bulk of external security assistance directed toward the FMS.19 Donors failed to hold Farmaajo accountable to the London deal, and funding was redirected exclusively to federal forces that were subsequently deployed more aggressively against domestic opposition than against al Shabaab – early indicators of Villa Somalia’s broader political swerve away from federalism toward a centralized, unitary state.20 Momentum against the militants was lost, and the federation began to fray at the seams. AMISOM’s name was optimistically changed to the AU Transitional Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), with no end to the “transition” in sight.

Since HSM assumed the presidency for a second time in 2022, the federal government’s posture toward the AU mission has whiplashed wildly, alternating between demands for a drawdown, strategic pauses, and requests for more troops. Soon after HSM took office, clan militias in the Hiiraan region, collectively known as Macawiisley, launched a series of successful operations against al Shabaab and made significant territorial gains. The FGS initially supported these efforts by deploying U.S.-trained Danab special forces to assist with intelligence, targeting, and coordination. But from mid-2023, as Villa Somalia attempted to wrest leadership of the campaign away from local clans and place it under SNA command and control, it foundered and collapsed, enabling al Shabaab to recover lost ground.

Nevertheless, in early 2024, Villa Somalia demanded that ATMIS draw down to less than 12,000 troops by the end of the year, dismissing AU objections that the mission would become untenable. Exactly a year later, with al Shabaab resurgent across south central Somalia, the FGS made an abrupt about face and called for an 8,000-strong ATMIS “surge.” Since Mogadishu’s erratic juggling of AU force levels cannot be explained by progress on the battlefield, a more plausible explanation—based on candid discussions between Somali officials and their foreign counterparts—relates to Villa Somalia’s misplaced expectation that resources spared from the AU mission would simply be reallocated to the SNA.

International partners are becoming queasy about funding a Somali military establishment that is increasingly deployed against political opponents rather than al Shabaab.International partners are becoming queasy about funding a Somali military establishment that is increasingly deployed against political opponents rather than al Shabaab.21 A SNA offensive against the Jubaland administration in 2024 degenerated into a fiasco as hundreds of defeated federal troops fled across the border into Kenya and left many international partners fuming over the FGS’s misuse of security assistance to fight its own FMS instead of al Shabaab. In mid-2025, deliveries of arms from Villa Somalia to FGS-aligned militias in Puntland and Jubaland compelled both state governments to divert attention and resources away from counterterrorism operations. Since July 2025, federal forces have revived efforts to wrest Gedo region away from Jubaland, triggering intermittent clashes along the Ethiopian and Kenyan borders.

Some foreign governments have subsequently begun recalibrating their security partnerships in Somalia. In recent months, the United States, UAE, Ethiopia, and Kenya have all provided direct support for the Puntland government’s vigorous ground campaign against Islamic State fighters, dismantling their northern stronghold and disrupting the terror group’s global financial operations. In southern Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia have signaled their growing displeasure with Mogadishu’s belligerence toward the Jubaland administration, with which they both cooperate to ensure border security.22

AUSSOM has received barely a quarter of the $166 million mission budget for 2025, while shouldering more than $100 million in arrears from the previous year.23 Expected contributions from the EU and other donors are unlikely to fill the funding gap, but they may enable AUSSOM to limp into 2026 in a diminished form and with deep uncertainty about its longevity. Whether or not international partners rediscover any appetite to continue funding at levels needed to sustain the mission may be partly influenced by Somalia’s political outlook beyond the expiry of HSM’s term of office in May 2026.

Outlook

As the clock runs out on HSM’s second presidential term, Somalia is lurching toward the brink of an even deeper constitutional, political, electoral, economic, and security polycrisis—much of which is self-inflicted. The FGS’s “Hobson’s choice” between a lopsided election or no election at all threatens to strain the country’s unstable political settlement beyond the breaking point, bringing armed opposition into the streets of Mogadishu and leaving the federal government even more isolated and enfeebled than it is at present. Donor forbearance of the status quo, entailing continued financial support and funding of AUSSOM’s costs, will be strongly tested. Meanwhile, al Shabaab’s strategic calculus is steadily shifting in favor of seizing the capital.

Hopeful portrayals of al Shabaab as a reasonable political actor and potential partner in Somalia’s governance are unfounded and untested. The group’s own messaging—including a September 2025 video that decries constitutional rule, women’s rights, music, and dancing as forms of heresy—leaves no reason to doubt that it intends to establish a totalitarian theocracy in Somalia more akin to Taliban rule in Afghanistan than to Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham’s awkward embrace of constitutional democracy in Syria. Any attempt to negotiate a settlement between Villa Somalia and al Shabaab will almost certainly be rejected by Puntland and Jubaland, which have persistently defended their autonomy from Mogadishu and have battled the jihadists more consistently and, relatively speaking, more successfully than the FGS. Al Shabaab attacks on Kenyan and Ethiopian troops in border areas would likely accelerate and intensify unless some kind of diplomatic entente were reached. But this would leave the rest of Somalia more vulnerable to al Shabaab’s destabilization and aggression, potentially heralding a new chapter in Somalia’s civil war. Meanwhile, the divergent interests of rival regional powers are more likely to escalate and entrench the conflict, as in Sudan, rather than to curb and contain it.

Al Shabaab can only be defeated through simultaneous military action on multiple fronts, with the strategic objective of dismantling their strongholds in the Juba River Valley and southwest Somalia.Pulling Somalia back from the abyss and on course to recovery may still be possible, but it is primarily a political challenge rather than a military one. Al Shabaab can only be defeated through simultaneous military action on multiple fronts, with the strategic objective of dismantling their strongholds in the Juba River Valley and southwest Somalia. This, in turn, can only be achieved by coordinated deployment of FMS security forces, with select federal units in a supporting role. This demands a level of trust between FGS and FMS political leaders that currently is lacking.

The HSM administration appears to be more focused on sidelining and subordinating the FMS instead of enlisting their support in a joint effort to fight al Shabaab. By doing so, they apparently underestimate Mogadishu’s vulnerability to an al Shabaab offensive. International partners are confronted with a choice between whether to intervene urgently and forcefully enough to induce a course correction in the coming months, or to allow events to unfold while they consider longer term implications and options.

Government of National Unity

Forging a cohesive national coalition against al Shabaab is probably unachievable short of restructuring the FGS as a government of national unity. As a first step, HSM would need to convene an emergency conference of FMS leaders to initiate the process of restoring trust and to agree on a common military strategy. But with frictions so high, confidence so low, and time so short, rebuilding trust between HSM and other political leaders will be an uphill task. The involvement of genuine honest brokers would probably be indispensable.

Convincing FMS leaders and other political forces that Villa Somalia is serious about power sharing will depend on whether HSM is prepared to return to the core principles of the Provisional Constitution—notably a rules-based, consensus-oriented approach to constitutional amendments and organic legislation that affects the interests of the FMS. This would mean reverting to the original text of the 2012 Provisional Constitution and conducting of indirect federal elections by May 2026. Confidence in the electoral process would be immeasurably enhanced if HSM were to appoint a genuinely neutral independent federal elections management body to oversee the preparations and implementation of the vote—and to announce that he will not stand for another term. Some observers may be disappointed by the prospect of another clan-based, indirect election in May 2026, but a smooth political transition anchored in tried and tested methods is preferable to a dangerously contentious and contested electoral experiment or a presidential term extension.

The greatest asset of the anti-al Shabaab forces is not their combined military might but the promise of a better life than under al Shabaab.On the military front, it will be essential to reconfigure Somalia’s National Security Architecture to integrate and empower FMS forces, including local defense militias. The 2017 Security Pact could serve as a framework for negotiations, assigning greater responsibility and resources to the FMS in planning and executing counterinsurgency operations. A high-level military coordination committee, with devolved functions in each FMS, should be established to develop a unified strategy to combat al Shabaab, shifting the center of gravity of fighting from central Somalia toward jihadist strongholds and headquarters elements in the southwest.

AUSSOM’s political autonomy should be reinforced, eliminating Villa Somalia’s political interference in the selection and deployment of national contingents. Subject to funding support, AUSSOM’s core mission should be to consolidate its achievements to date, secure vital FGS and FMS government sites and functions, and continue providing specific combat support functions for Somali offensive operations. AUSSOM participation in ground offensive operations should be authorized only in exceptional circumstances at the Force Commander’s discretion. Moreover, operational command and control should be substantially devolved to the sector level, enabling closer coordination with FMS security forces and community defense militias, in addition to the SNA.

The engagement and support of external partners would greatly enhance the prospects of success. International partners should be prepared to show flexibility in the rebalancing of “train and equip” programs, as well as resource allocations, by giving equal priority to FMS and community defense forces, in line with a reconfigured National Security Architecture and strategic plans.

Collapse and Containment

In a worst-case scenario, Villa Somalia’s rejection of a national unity government need not obstruct concerted action against al Shabaab, since FMS and other Somali political forces could, independently of the FGS, join forces against this common threat. Ethiopia, Kenya, the UAE, and the United States have convincingly demonstrated the value of partnership directly with state and local forces and should retain this option.

By the same token, al Shabaab’s potential capture of Mogadishu need not foreshadow a total jihadist conquest of Somalia. A Provisional Federal Government, comprising FMS, regional authorities, and other political forces, could be established in a secure interim capital, preserving the core functions of statehood while exercising de facto territorial control over more than half of Somalia’s territory between the Gulf of Aden and the Kenyan border.

The balance of forces between a Mogadishu-based al Shabaab and a Provisional Federal Government located, for example, in Baidoa, would initially be evenly matched but increasingly unstable. In addition to the symbolic value of controlling the national capital, al Shabaab’s full access to Mogadishu port revenues would potentially triple its income overnight. Since the militants would stand to inherit most of the arms, equipment, and vehicles currently in the SNA’s possession, al Shabaab’s military capabilities would rapidly surge.

On the other side of the military equation, security forces in the States of Puntland, Jubaland, and the region of Hiiraan, among others, have already proven far more effective in battle than federal troops. They have also been more resistant to Islamist influences that seek the creation of a theocratic government. With cross-border support from Ethiopia and Kenya, fortified by regional and international allies, they would stand an even greater chance of containing al Shabaab advances, while preparing the ground for a concerted counteroffensive against vital al Shabaab strongholds in the Juba and Shabelle Valleys.

The greatest asset of the anti-al Shabaab forces, however, is not their combined military might—it is the promise of a better life than under al Shabaab. Somaliland, Puntland, and to a lesser extent some other FMS administrations, have proven that they are capable of providing not only peace and security, but also economic opportunities and personal freedoms that al Shabaab would never countenance. Unless a new government of national unity or provisional authority holds genuine promise of better days to come, then Somalia’s future will be as dark as al Shabaab’s black banner.