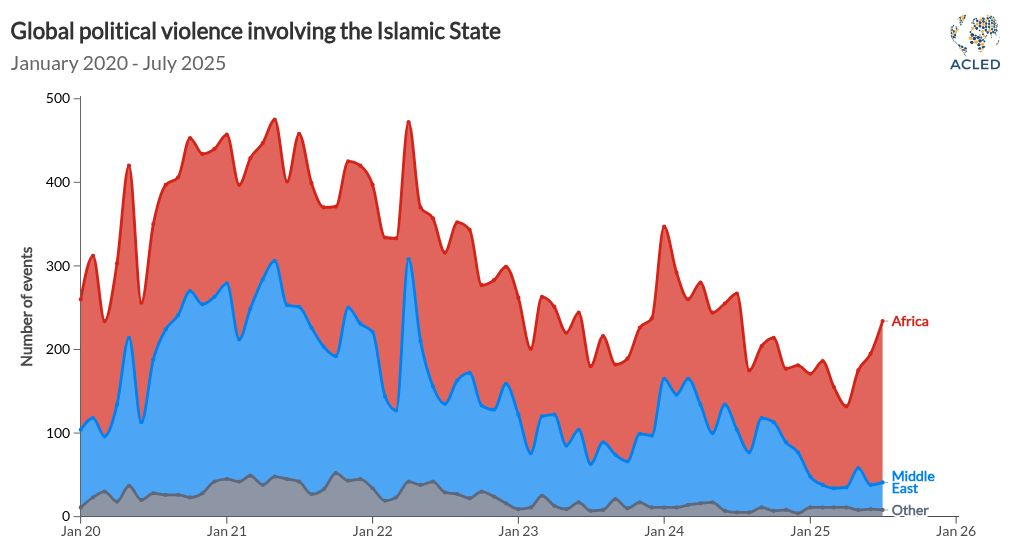

The Islamic State is increasingly pivoting its operations toward Africa, where it maintains the capacity to coordinate violence across a broad area, generate financial resources, and expand its recruitment base. Over two-thirds of the Islamic State’s global activity in the first half of 2025 was recorded in Africa (see graph below). This pivot to Africa comes as the group’s propaganda also focuses more and more on its operations in Africa, with its affiliates gaining influence and prestige in the global IS network. This surge in activity raises urgent questions about the Islamic State’s capacity for violence in Africa, its strategies, and the threat it poses to regional governments and the world.

In this Q&A, ACLED’s experts break down how IS affiliates in Somalia, the Sahel, the Lake Chad basin, the Great Lakes region, and northern Mozambique operate across the continent, how they engage with the IS global network, and how local governments and international partners are responding to this growing threat.

Where exactly do these Islamic State groups operate, and are they expanding?

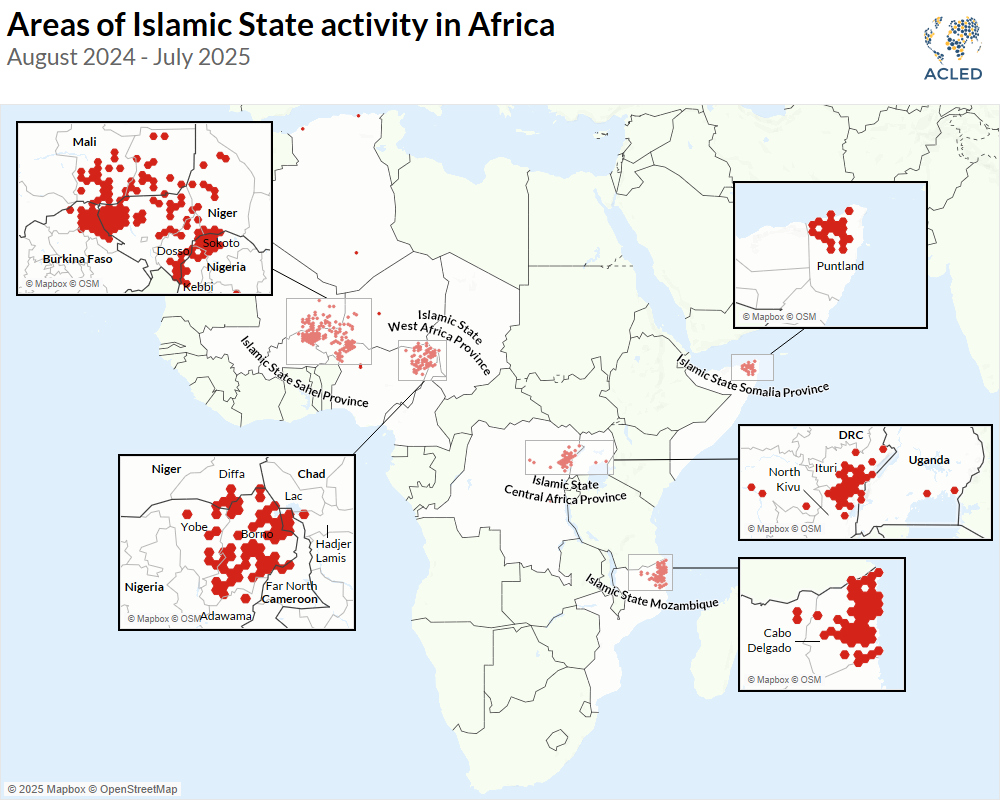

Héni Nsaibia: The group’s so-called Sahel province, ISSP, operates mainly in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, especially in the area known as the tri-state border region (or Liptako-Gourma), where the three countries intersect. Since the beginning of 2024, it has expanded its operations southward along the Niger and Nigeria borders, in particular in Niger’s Dosso region and Nigeria’s northwestern Sokoto and Kebbi states.

Miriam Adah: In the Lake Chad Basin, the group is referred to as the West Africa province, or ISWAP. So far in 2025, the group has exploited the porous borders in the region following the shortcomings in military cooperation of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), after Niger exited in March 2025, and Chad threatened withdrawal in late 2024. ISWAP has been increasingly focused on attacking Nigerian military bases in the northeastern states of Borno and Yobe, using IEDs and ground operations against military forces, and recently gained numerous foreign militants in Niger’s Diffa region.

Dr. Ladd Serwat: In and around the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Islamic State Central African Province, or ISCAP, is known locally as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF). The group operates in northern North Kivu and southern Ituri. Though less frequent than in the DRC, ISCAP also carries out attacks in Uganda via cross-border raids or through clandestine cells operating in Uganda. After more than a year without ISCAP-related violence in Uganda, the group conducted a failed suicide bombing on the outskirts of Kampala on 3 June, a Christian holiday in Uganda called Martyrs’ Day. The bombing reportedly killed only the bomber herself and her motorcycle driver.

Mohamed: Despite the recent prominence of IS Somalia within the organization’s global operations, the group carries out limited violence in Somalia. IS Somalia operates out of the Golis mountain range in Puntland’s Bari region at the tip of the Horn of Africa. In recent years, IS Somalia made notable territorial gains but has come under sustained pressure from counter-offensive operations by Puntland forces since late 2024. These operations have resulted in Puntland state forces gaining control over several of IS Somalia’s stronghold positions, including Turmasaale and Sheebaab villages.

Peter Bofin: IS’s Mozambique outfit has its heartland in Macomia and Muidumbe districts in northern Cabo Delgado province, particularly along the Macomia coast, in inland forests, and along the Messalo river basin. However, in 2025, it has also undertaken brief operations in Niassa province to the west in May, and in southern Cabo Delgado province in July.

As the Islamic State aims to expand its influence across Africa, it often contests with state security forces to maintain its bases or expand across broader areas. However, it’s also widely known for its violence against civilians, both those within its territories of control and when taking over new areas. How prominent is civilian targeting by these IS affiliates?

Héni: Notorious for committing mass atrocities around the Sahel, ISSP has in recent years attempted to portray itself as a governance actor. The group enforces strict Sharia law, regulates local markets, and conducts sermons, or dawa, to build legitimacy among the people living in its areas of control or influence. Yet, it still uses extreme violence to subdue this same population by targeting military forces, militias, and civilians alike to quell resistance. At the same time, it has intensified high-value kidnappings — which are often outsourced to local bandits — as a growing source of revenue. These operations supplement the income the group receives from extortion, cattle theft, artisanal gold mining, looting, and taxation of communities within its expanding areas of control.

Miriam: ISWAP directly contests state control through targeted attacks on state forces, increasingly engaging in complex attacks that have overrun multiple military bases in the Lake Chad Basin, and especially in Nigeria’s Borno State. The group also actively targets Christian-majority villages; it abducts civilians for ransom and sets churches ablaze in areas that are home to large Christian communities, such as Chibok. While Boko Haram attacks Christians and Muslims alike, ISWAP largely views Christians as “infidels.” IS Central’s al-Naba propaganda reports feature claims of attacks on Christians and their places of worship. ISWAP also distributes pamphlets with Islamic teachings and organizes sessions to teach civilians the benefits of having an Islamic state, as part of its propaganda.

Ladd: Civilians in the DRC, and sometimes Uganda, are frequently violently targeted by ISCAP. The group often publicizes these mass casualty massacres through IS Central and ISCAP media. One such report was of a string of attacks that included the reported killing of at least 36 civilians in the Bapere sector on 13 August. While these attacks are framed as targeting Christians, they typically devastate entire communities regardless of religion. The group avoids direct confrontations with military forces but has recently consolidated its camps to make sure each group has sufficient fighters to defend against Uganda’s heightened military presence.

Mohamed: IS Somalia carries out attacks on both Puntland state forces and civilians, and faces competition for control of Puntland’s Bari region from al-Shabaab. The group also uses violence to generate an income: Militants have heavily targeted pastoralists and businesses to collect extortion money, but in July, local pastoralists resisted the extra payment requirements by IS Somalia, leading to clashes that resulted in multiple people being killed on both sides.

Peter: ISM operates mostly in small groups, primarily targeting civilians in Cabo Delgado through fatal attacks, abductions, and destruction and looting of property. In 2025, looting and abduction have become more pronounced as the group seeks to source basic supplies and raise cash through ransom. It also carries out attacks on under-resourced Mozambican military outposts, but limits its engagement with Rwandan intervention forces.

How do these groups fund their operations, recruit people, and acquire weapons? Are they supported by any local communities?

Héni: Fear, a lack of state presence, and grievances among marginalized communities in remote border areas enable ISSP’s survival. The group has multiple, diverse revenue streams in the Sahel, as previously mentioned. It acquires weapons through battlefield captures and cross-border smuggling, as well as local manufacturing of explosive devices. Recruitment is carried out through coercion; ideological indoctrination, including of children; and the exploitation of ethnic tensions and socio-economic grievances, particularly among marginalized communities. Despite ISSP’s strict rule enforcement and basic governance provision in the areas under its control, local support varies, ranging from passive compliance to active resistance.

Miriam: Similarly, ISWAP obtains its labor force largely through coercion, but economic factors also entice some recruits to the group due to promises of better standards of living as a fighter for the group. Its revenue consists of ransom payments and taxes imposed on civilian communities, including fishers around Lake Chad. While some of their weapons are from the Islamic State and other affiliate groups in the region, much of ISWAP’s arsenal comes from ransacked military bases, camps, convoys, and deserting soldiers.1 This trend has intensified in 2025, as ISWAP launched several sophisticated attacks on military bases in Nigeria’s Borno state.

Ladd: Originally a Ugandan rebel group, ISCAP still draws recruits from Uganda, but also from the DRC and across other areas of eastern Africa. ISCAP generates funds and resources by looting villages and relying on pillaged resources. Further, the group often abducts civilians for forced labor or marriage. Collectively, the decimation of villages and use of rural camps show ISCAP’s lack of interest in governing many of the areas where the group operates. While most weapons are acquired locally through arms trafficking or clashes with militias and state forces, ISCAP militants have also learned bomb-making skills from Islamic State trainers operating across eastern and southern Africa.2

Mohamed: As I mentioned in the previous question, IS Somalia sustains its operations primarily through extortion and illicit taxation of businesses. In Bosaso, the group reportedly demanded up to $500,000 from local businesses in 2023.3 The city’s strategic coastal positioning also allows access to arms trafficking networks operating between Yemen and Somalia, with militants using existing weapons smuggling networks that operate across several coastal regions in Somalia. IS Somalia recruits defectors from al-Shabaab and enjoys support from local communities, including the prominent sub-clans of the Majeerteen clan, especially the Ali Saleban sub-clan in the Bari region, which the group’s leader, Abdulkadir Mumin, is from.

Peter: Armaments are mostly seized in operations against the Mozambican military. In 2022, ISM started to produce and deploy IEDs. Technical assistance is thought to have come from the DRC, where ISCAP’s IED use increased noticeably in 2021. Recruits come from northern Mozambique, Tanzania, and other countries in the Great Lakes, particularly the DRC — reflecting connections with ISCAP — while some are abducted into the group, including children. Networks in towns and cities in the north support supply and financing networks that supplement ISM’s looting and ransom activities. ISM actively seeks support in some coastal and nearby areas that are predominantly Muslim, and where some leaders originate, but this is tempered by its intimidation, looting, and extortion of these same communities.

What is the current relationship between these local Islamic State affiliates and the IS global network?

Héni: Ties to IS Central remained tenuous for years after the group first pledged allegiance without official recognition in 2015. However, IS Central formally integrated ISSP, then known as Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, into ISWAP in March 2019 as a separate subgroup. ISWAP operatives were deployed to oversee and support ISSP’s growth, while regional affiliates in Libya and Nigeria facilitated propaganda, strategic guidance, and financial support. Since gaining status as an IS province in March 2022, ISSP has remained largely self-sustaining while being fully embedded within the Islamic State’s global structure and media ecosystem.

Miriam: Since it emerged from a split with the previously IS-aligned Boko Haram in 2016, ISWAP has been the official IS affiliate in the Lake Chad basin. Propaganda showcasing ISWAP’s activities is often published by the Islamic State’s media. Evolutions in ISWAP activity in recent years, though, point to collaboration in terms of training with its global network. In particular, the resurgence of IED attacks in 2024 indicates that training was provided to the group to replace lost fighters. ISWAP has also modified its strategy by using drones to carry out attacks, likely as part of a technological transfer by the global IS network to other localized branches like ISWAP.

Ladd: Musa Baluku, a Ugandan and former imam who joined the group in 1994 before becoming the current leader of ISCAP in 2015, steered the group toward IS affiliation. By 2020, the ADF formally rebranded as ISCAP. Previous leadership had long resisted integration with IS, but evidence of a connection with IS slowly emerged under Baluku’s leadership as the group increasingly drew on foreign fighters or trainers to increase capacity and move finances.4 IS Central has more frequently published propaganda about ISCAP operations over the past year — often within days of attacks — signaling closer coordination and stronger integration into IS’s global messaging infrastructure.

Mohamed: There is a strong relationship between IS Somalia and IS Central. Not only does IS Central view Somalia as a burgeoning operational area for its global operations due to its strategic location and the weakness of the Somali government, but IS Somalia also hosts IS’s regional coordination hub: the al-Karrar office. IS Somalia is one of IS’s most profitable branches and, as such, serves as the financial hub for the wider IS network in Africa and beyond. Its importance extends far beyond the region, though. Even if Mumin, IS Somalia’s leader, is not the head of IS Central as some reports have suggested, he is widely acknowledged to be one of IS’s most senior leaders globally.5

Peter: ISM draws heavily on support from regional IS affiliates. It has documented ties with ISCAP in the DRC — the source of its IED manufacturing capacity — and IS support networks in South Africa and Somalia. Islamist networks in Tanzania are also a source of support in accessing finance and moving people. ISM has received funding through the al-Karrar office in the past and has strong and ongoing relations with IS media operations, as reflected in regular reporting in their outlets through a consistent IS style.

Given the threat to governance, economies, and civilians, how are local governments responding?

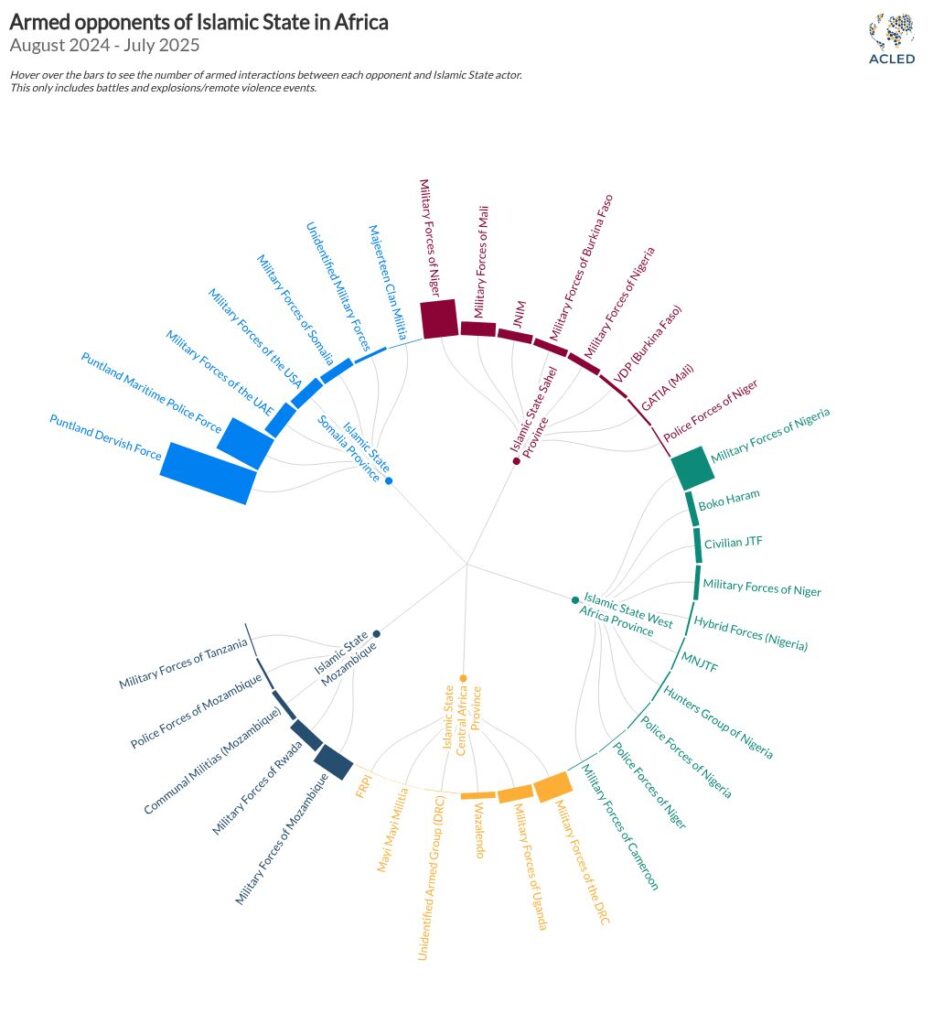

Héni: Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have responded to the ISSP threat primarily through military and security operations, both unilaterally and through occasional regional coordination. Mali has also received support from Russian partners, initially through the Wagner Group and more recently the Africa Corps. Where state presence is limited, authorities rely heavily on militias and self-defense groups. These include Burkina Faso’s state-backed Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP) and community-based self-defense groups in Mali and Niger, but these forces have struggled to contain and resist ISSP. The main bulwark against ISSP’s expansion, however, has been its al-Qaeda-affiliated rival Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin. These groups fought intensely between 2020 and 2023, but both seem to be prioritizing fighting state forces and militias since.

Miriam: The spread of the group across the Lake Chad region led to the birth of the MNJTF, whose troops came from Nigeria, Niger, Benin, Chad, and Cameroon. Recent coups and internal political tussles in Niger and Chad have threatened the stability of the MNJTF, leading to a lack of coordination among member countries and the withdrawal of Niger’s troops from the task force in 2025. Chad also threatened to withdraw its troops and support in 2024. Independently, the Nigerian military carries out special military exercises in the region and has gradually evolved into training and deploying designated units for this sole purpose. The French military provided some support to the MNJTF until 2023, when it exited Niger.

Ladd: The Congolese military deals with ISCAP through security partnerships with Uganda and local militias. It launched joint operations with the Ugandan army in 2021 to counter ISCAP’s growing threat. However, local militias and Ugandan forces have taken a more prominent role in confronting ISCAP in more recent years, as the Congolese army struggles to sustain pressure on multiple fronts, exacerbated by the recent resurgence of the March 23 Movement rebellion. Joint Ugandan-Congolese operations have pushed the militants westward since 2024. Notably, on 10 July 2025, Ugandan forces claimed that they captured ISCAP’s largest camp in Apakwang, Ituri Province, commonly called Madina.

Mohamed: The Puntland administration’s security forces have maintained an ongoing operation targeting IS Somalia stronghold positions in the Cali Miskat mountain range in the Bari region since December 2024. There, security forces have gained control over several IS stronghold villages, destroyed hideouts, and killed and captured senior IS members. The United Arab Emirates and United States support these operations through both military aid and airstrikes.

Peter: Mozambique currently relies on troops from Rwanda and Tanzania to support its counter-insurgency efforts against ISM. Of the two, Rwanda is the most important, as it has over 4,000 troops deployed across the north of the province, but concentrated around the TotalEnergies natural gas project. A two-and-a-half-year military intervention by the Southern African Development Community ended in 2024, with Mozambique preferring bilateral arrangements over complex multilateral support.