A fuel blockade imposed by al-Qaeda-aligned militants has paralyzed the capital of Mali and roiled its repressive military government.

BAMAKO, Mali — After years spent accumulating arms and influence in rural parts of this West African nation, al-Qaeda-aligned militants have shown their power now extends to the heart of the state — imposing a fuel blockade that has paralyzed the Malian capital and threatens its military government.

Scores of humanitarian and commercial flights have been canceled or rescheduled. International embassies and nonprofits are stockpiling supplies and planning for worst-case scenarios. In Bamako, which has largely been spared the effects of the violence and instability gripping much of the rest of the country, frustrated residents spend hours searching for gas. Cars and motorcycles jostle for space in long lines snaking from the few open stations. Blackouts are spreading.

“The emergency is here, and the situation is very, very critical,” said Bamako resident Aboubacrine Ag Ali, 62, in an interview last week. He has been mostly stuck at home for weeks, unable to afford taxi fares that he said have doubled since early September, when a spokesman for the Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin militant group, or JNIM, declared it would block nearly all fuel imports into Mali.

The United States recently stepped up intelligence sharing with the junta, hoping to stanch the militants’ momentum. But they are only getting stronger.

“They are everywhere,” ag Ali said of the insurgents. “Everywhere.”

Experts put JNIM’s fighting force across the Sahel at around 6,000, a seemingly small figure in a nation of nearly 25 million. But the group has managed to solidify its rule — and win popular support — across vast swaths of Mali and neighboring Burkina Faso, and now menaces coastal nations such as Benin, Togo and Ghana. The group’s crippling fuel blockade, according to Malian and Western officials as well as analysts, is an expansion of its strategic economic warfare — and its most significant show of strength to date.

JNIM initially said the blockade was a response to government efforts to restrict fuel sales in areas it controls. In a statement Friday, the insurgents declared the siege would continue until the junta fell or agreed to apply “Islamic sharia law” nationwide. All women traveling outside Bamako, whether on public transport or in private cars, must wear the hijab, the statement decreed.

Militant leaders have expressed some openness to negotiating with the government, three Malian and Western officials said, but only if such talks are made official, giving the group the legitimacy it has long sought. For years, as its fighters have battled state forces, JNIM has formed governance agreements with local communities, often with tacit, but never formal, approval from national authorities.

Mali’s military leaders — who vowed to restore security when they took power in a 2021 coup d’état — have so far rejected the possibility of talks, the three officials said, speaking to The Washington Post on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. Instead, they said, the regime seems committed to doubling down on its strategy of all-out war.

The militants “want to paralyze the country, to turn the people against their state,” said Moussa Ag Acharatoumane, a member of Mali’s transitional government. “But the state will fight back.”

In partnership with Russian mercenaries, first with the Wagner Group and now with the Kremlin’s rebranded Africa Corps, Malian soldiers have waged a scorched-earth campaign in areas controlled by JNIM, killing thousands of civilians, according to rights groups.

The long-term objectives of the insurgency remain unclear, experts say. But the blockade has clearly demonstrated “both JNIM’s growing capacity — and the state’s incapacity in responding effectively,” said Héni Nsaibia, West Africa senior analyst for the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data project, or ACLED.

Neither Mali’s military spokesman nor its Foreign Ministry responded to requests for comment.

JNIM’s pressure campaign in Mali has major ramifications for the rest of the Sahel, where other military regimes have proved similarly unable to contain the group and face additional threats from the regional Islamic State affiliate.

“I have been covering these countries for a long time, and I have never been so worried about their futures,” said Ibrahim Yahaya Ibrahim, deputy director of the International Crisis Group’s Sahel project. “If one of these countries falls,” Ibrahim said, referring to Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, “the rest will be in trouble.”

The war comes home

In this usually lively capital city in Mali’s south, many residents were only dimly aware of JNIM’s strength, which is most pronounced in the sparsely populated north.

“We had known terrorism was a problem,” said Seydou Touré as he pushed his motorcycle down the highway on a blisteringly hot Saturday afternoon in search of gas. “But this showed how capable they are,” he continued. “It surprised us.”

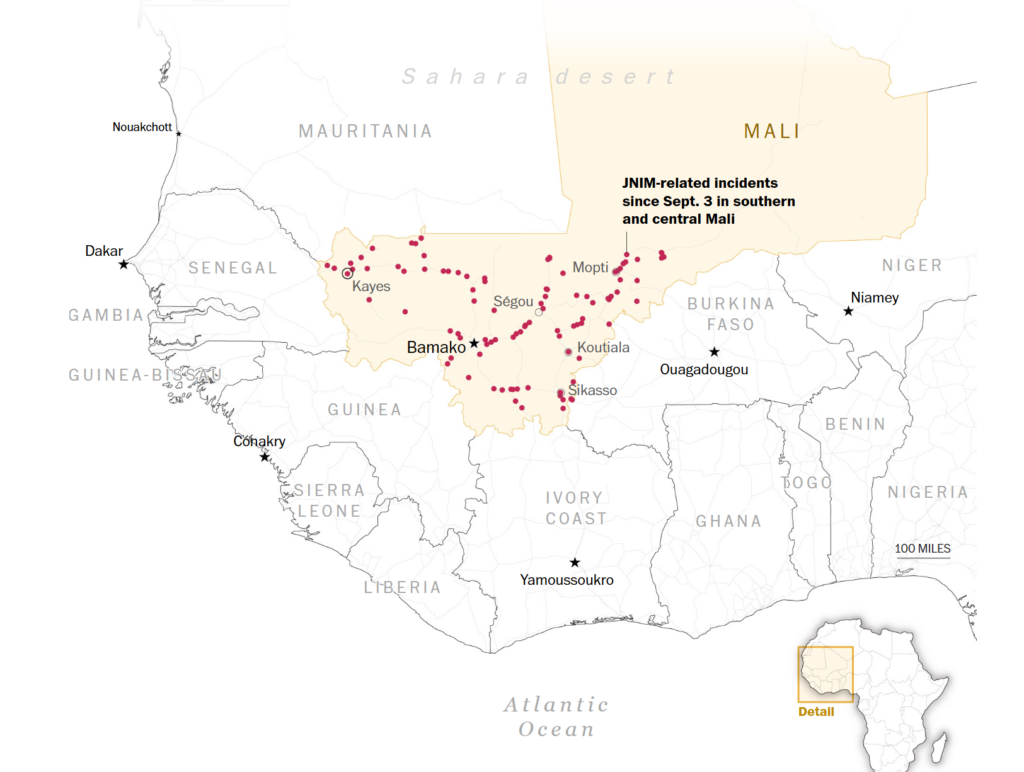

The blockade officially began Sept. 3, when a JNIM spokesman announced in a video that the group would obstruct fuel imports from Senegal and Ivory Coast, the countries that provide landlocked Mali with the vast majority of its fuel, along with Guinea and Mauritania. The spokesman also said that citizens were prohibited from leaving Kayes, near the border with Senegal, and Nioro du Sahel, near the border with Mauritania.

In the days that followed, militants kidnapped six Senegalese truck drivers on the Malian side of the border and repeatedly set fire to fuel trucks coming from Senegal and Ivory Coast. On Sept. 14, the group attacked a convoy of more than 100 fuel trucks escorted by the Malian army, according to ACLED, burning 51 trucks and killing a number of soldiers. The attacks have continued in recent weeks, with videos of blazing tankers circulating widely on social media.

Outside Bamako, the effects were felt almost immediately, producing long lines at gas stations from Mopti, northeast of Bamako, to Kayes in the west.

The United Nations — which runs flights across the country to support its humanitarian work — was forced to start pulling from the government’s emergency fuel stockpile in the third week of September, according to a person with direct knowledge of the supplies who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive situation. The price of jet fuel has more than doubled, the person said, contributing to a rash of canceled and delayed flights.

Early this month, the shortages began to be felt in Bamako, a sprawling city built along the banks of the Niger River that is home to about 20 percent of Mali’s population. Most of the gas stations here have closed; cars and motorcycles throng the few that still have working pumps.

A store owner said many of his shelves were empty because commercial truck drivers from Senegal are too scared to travel. Power outages — already a problem before the blockade — have gotten worse, he said, because there was not enough fuel to power the electrical grid. In Mopti, Mali’s third-largest city, three residents told The Post they had been without electricity for more than two weeks.

The situation is “the worst I’ve seen,” the store owner said on a recent afternoon in Bamako, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he feared reprisals from Mali’s increasingly repressive military rulers. “And I fear worse is coming.”

‘Too much death’

JNIM was founded in Mali in 2017 as an umbrella organization combining four Islamist extremist groups, and its leaders pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda. Headed by Iyad ag Ghali — a diplomat turned militant from the north — and Amadou Koufa — a preacher from central Mali — it has largely focused its violence on military and government targets as opposed to civilians, helping it build grassroots support in far-flung communities neglected by the state.

In the areas JNIM controls, it is now operating with increasing confidence and visibility, said Wassim Nasr, a Sahel specialist and senior research fellow at the Soufan Center. He pointed to recent propaganda videos showing well-armed combatants driving around a Malian town near the border with Burkina Faso in an easily identifiable car.

Experts say JNIM has signed agreements with local communities across the Sahel, usually requiring adherence to the group’s strict interpretation of Islamic law — including paying zakat, or tax, in exchange for peace. Often, according to experts, the government is aware of these agreements and does not try to get in the way, an acknowledgment of its ever-shrinking power.

Alioune Nouhoum Diallo, a former president of Mali’s parliament who has been involved in local negotiations with militant leaders, told The Post it is time for the government to consider engaging with Ag Ghali and Koufa in a national dialogue about the future character of the state.

One possible outcome, he said, would be that Mali becomes an Islamic republic, like neighboring Mauritania. “There has been too much death,” Diallo said in an interview in Bamako. “And the solution the military has put in place has reached its limits.”

While some diplomats in the capital fear a Taliban-style takeover of the country, others believe JNIM is more interested in a power-sharing agreement — or in bringing down the current government in the hope that it would be replaced by a friendlier regime, allowing the group to expand the already massive smuggling networks it uses to move drugs, weapons and cattle across West Africa.

“I think everyone is stumped on the way forward,” said one of the Western diplomats. “But if this government goes down, it is not clear what other options there are.”

Ag Acharatoumane, the member of Mali’s transitional administration, said the government is not yet willing to negotiate with JNIM. But in the long term, he said, “dialogue with those who wish to engage should be considered.”

No escape

Ag Ali, the Bamako resident, who fled from Timbuktu a decade ago as violence by Islamist militants and separatists racked the north, feels stuck. A musician and an artisan, he said life in the capital had been difficult, but at least his family was safe.

Now, the blockade has disrupted their lives and thrown their future into doubt. His loved ones have been largely sequestered at home for weeks; traveling to other parts of the country to perform was out of the question.

“To flee only to find you didn’t really flee,” he said, pausing. “I don’t know what to say. It is painful.”

In interviews across Bamako, others gave voice to a similar mixture of fear, resignation and deep frustration — not just with the militants but with their leaders. Mali’s government has barred photography at gas stations, citing the “preservation of public order.” But residents saw it as the latest example of the junta’s crackdown on free speech and a futile ploy to salvage its public image.

“What I will say is that things are not right,” said Mohamed Sylla, 25, choosing his words carefully. He had pushed his motorcycle taxi for six miles looking for fuel. The authorities, he said, “need to do everything they can to find gas.”

A Malian analyst, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he feared reprisals by the state, said the government faced a deepening conundrum. Officials had few options left except to negotiate, he said, but worried negotiations would make them look even weaker.

JNIM, he said, “has created a psychosis in this country.”