Key Takeaways:

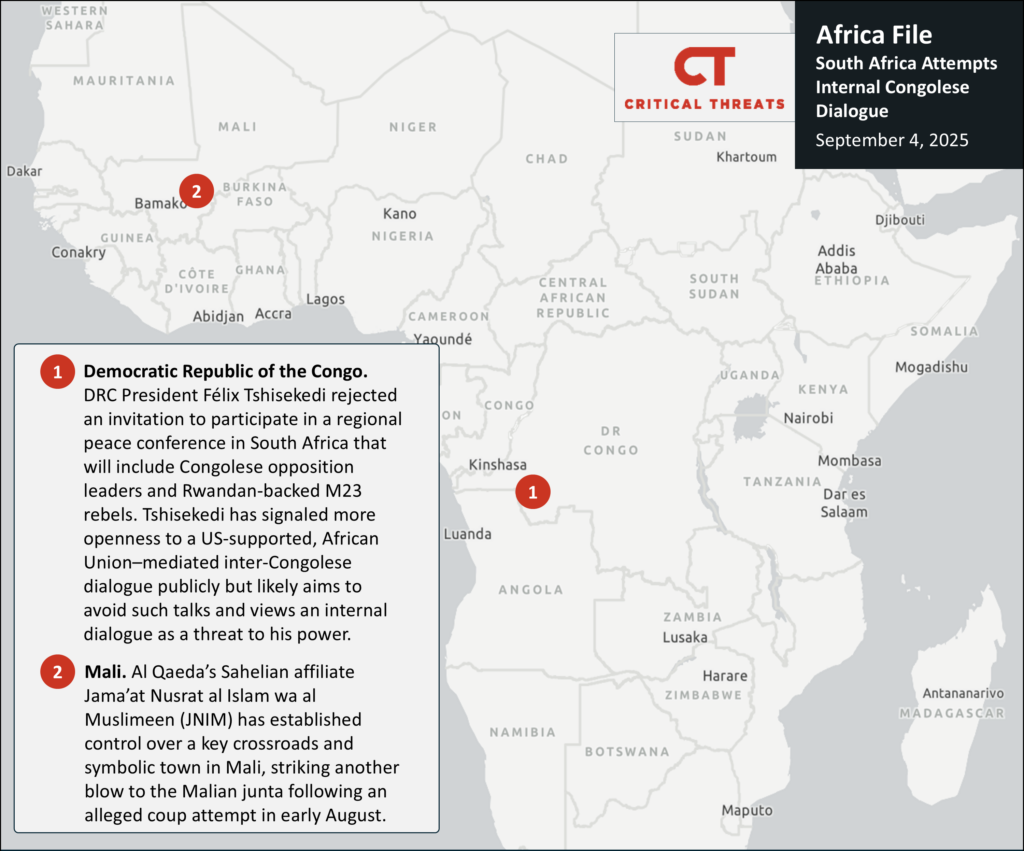

Democratic Republic of the Congo. DRC President Félix Tshisekedi rejected an invitation to participate in a regional peace conference in South Africa that will include Congolese opposition leaders and Rwandan-backed M23 rebels. Tshisekedi has signaled more openness to a US-supported, African Union–mediated inter-Congolese dialogue publicly but likely aims to avoid such talks and views an internal dialogue as a threat to his power.

Mali. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has established control over a key crossroads and symbolic town in Mali, striking another blow to the Malian junta following an alleged coup attempt in early August.

Figure 1. South Africa Attempts Internal Congolese Dialogue; JNIM Controls Farabougou: Africa File, September 4, 2025

Assessments:

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Former South African President Thabo Mbeki is set to host a regional peace conference with various Congolese opposition leaders and Rwandan-backed M23 rebels to discuss the security crisis in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Mbeki’s foundation is hosting the second annual African Peace and Security Dialogue conference near Johannesburg, South Africa, from September 3 to September 6.[1] Mbeki’s foundation plans to facilitate informal discussions on the political and security crisis in the eastern DRC, among other crises across the African continent.[2] The French magazine Jeune Afrique reported that Mbeki’s foundation likely aims to hold the informal talks outside of the DRC to “encourage people to speak without pressure.”[3]

Over 175 leaders will attend the conference, including Congolese civil society leaders, religious leaders, and several Congolese opposition figures.[4] Former DRC President Joseph Kabila, veteran opposition leader Moïse Katumbi, and at least six other opposition figures plan to attend.[5] Martin Fayulu, another opposition leader who has tried to balance his position between the opposition and DRC President Félix Tshisekedi, rejected the offer to participate, however, and said that the conference’s agenda was vague.[6]

The Congolese government has tried to prevent these opposition politicians from attending.[7] The Congolese government denied visas and held up travel for several opposition delegations slated to participate in the conference in South Africa.[8]

Mbeki’s foundation also invited the Congolese rebel groups to the conference. Corneille Nangaa, the head of M23’s political branch, said that M23 would send a “large” delegation to the conference.[9] Thomas Lubanga, the leader of a Ugandan-backed armed rebellion in the eastern DRC’s Ituri province, also said he would join the talks.[10]

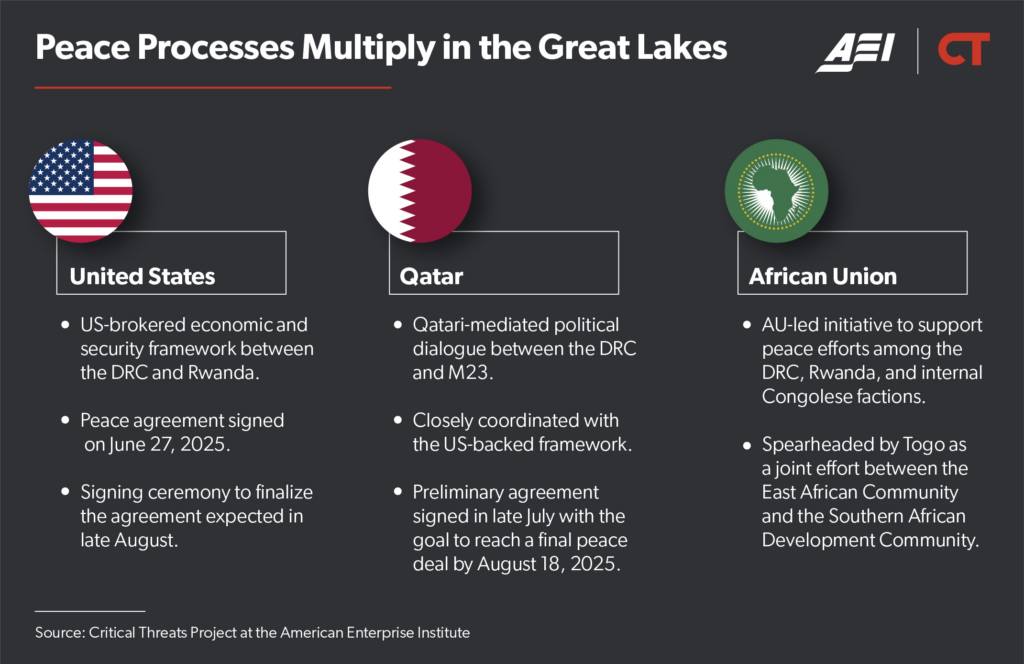

Tshisekedi rejected a formal invitation to participate in the conference because he likely views Mbeki as too close to his political enemies and sympathetic to M23. Other Congolese authorities are also unlikely to participate in the conference. Mbeki’s foundation invited close advisers to Tshisekedi and Vital Kamerhe, president of the National Assembly.[11] Kamerhe has been in South Africa—reportedly for a separate reason—since August 28.[12] The Congolese government officially declined an invitation to participate on August 28, which Congolese officials said was because it is already involved in several peace initiatives. Tshisekedi explicitly cited the DRC’s involvement in the US-brokered peace framework between the DRC and Rwanda, Qatari-led talks with M23, and an African Union–led initiative with Congolese religious authorities.[13]

Figure 2. Peace Processes Multiply in the Great Lakes

Tshisekedi likely views Mbeki as an unfavorably biased mediator for the crisis in the eastern DRC. Mbeki has blamed the eastern DRC conflict on Tshisekedi’s mismanagement and poor leadership, which he claims has been divisive and ineffective.[14] Mbeki hosted Kabila in South Africa in March 2025 as part of Kabila’s return to Congolese politics and has criticized the Congolese government’s prosecution against Kabila.[15] The Congolese communications minister called some of Mbeki’s recent statements “ignorant” and favorable to Rwanda and said that the Congolese government was uneasy about committing to another peace track led by someone who is “partisan” with respect to the eastern DRC conflict.[16] Tshisekedi said in a speech in late August that he would support a dialogue on the security crisis in the eastern DRC but “without Congolese people subservient to foreign countries.”[17]

add note

tweet

Tshisekedi has signaled more openness to a US-supported, African Union–mediated inter-Congolese dialogue publicly but likely aims to avoid such talks and views an internal dialogue as a threat to his power. Tshisekedi has held several meetings with Congolese religious leaders to discuss initiating a national dialogue in 2025. The dialogue is in close coordination with African Union mediators who have met with Tshisekedi and other Congolese opposition figures several times in 2025. The religious leaders presented Tshisekedi with a concrete plan in late August for Tshisekedi to initiate a dialogue and are awaiting his decision.[18]

US- and Qatari-led peace efforts support plans for a future inter-Congolese dialogue to bolster the long-term stability and viability of peace efforts. The African Union dialogue effort is closely coordinated with the US-brokered peace framework between the DRC and Rwanda. The draft Qatari-led agreement reportedly includes a plan to initiate a national dialogue in 2026.[19]

Tshisekedi agreed in principle to a dialogue but has set his own conditions and tried to stall the process. Tshisekedi has committed to explore the initiative but remained skeptical and impeded the process since March, making the leaders wait for months for his response and demanding that they collaborate with other religious denominations first before presenting their plan.[20] Tshisekedi said in a speech in late August that there would “never be any dialogue outside of my initiative,” indicating his aim to control any dialogue.[21] Tshisekedi has reportedly tried to exclude Kabila, Katumbi, and Nangaa from the dialogue, which would undermine the leaders’ initiative to create a fully inclusive process.[22]

Tshisekedi likely views the dialogue as a threat to his power. The religious leaders met with Nangaa and senior M23 officials in Goma in early 2025.[23] CTP assessed previously that Kabila likely aims to use his position to regain power in some form through a national dialogue.[24] The dialogue would include M23 and other rebellions and would ultimately aim to restructure power and the allocation of government positions across the DRC.

Mali

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) has established control over a key crossroads and symbolic town in central Mali. JNIM overran a Malian army base in Farabougou on August 19—100 miles north of the central Malian regional capital Ségou. JNIM fighters remained in the adjacent town in the proceeding days and took videos of Friday prayers on August 22.[25] The group has since signed an agreement with local leaders to allow civilians who had fled the town to return. Returnees must pay taxes and follow JNIM-interpreted shari’a law, including provisions on music, alcohol consumption, and clothing.[26] The group assassinated a dissenting local leader on August 31 in Dogofry, a nearby village 15 miles east of Farabougou, who had encouraged the Malian army to recapture Farabougou.[27]

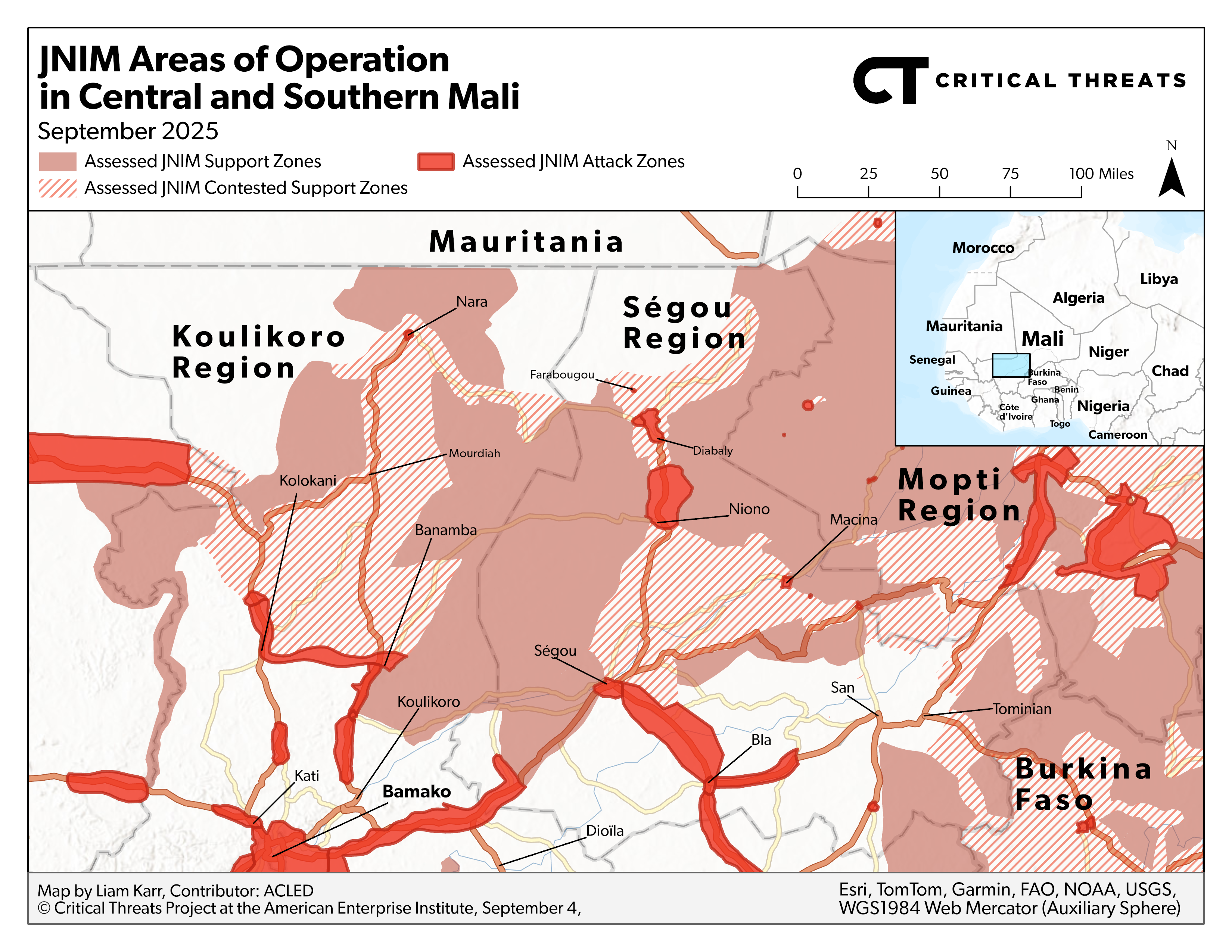

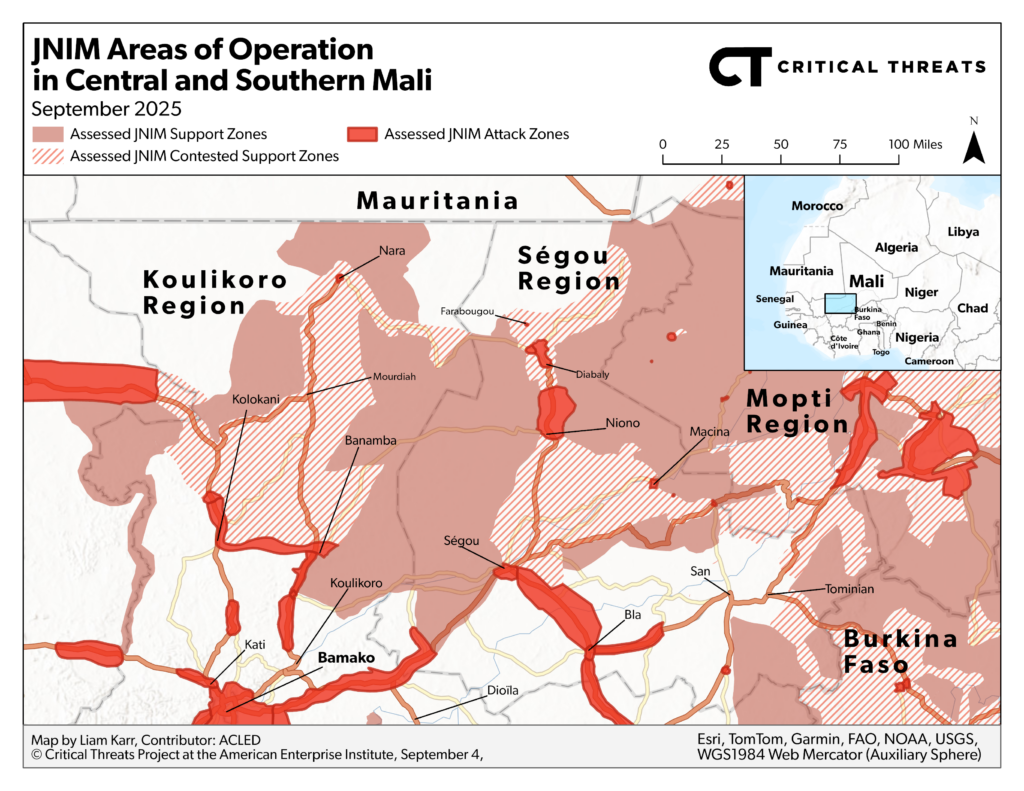

Figure 3. JNIM Area of Operations in Central and Southern Mali

The loss of Farabougou is an operational and symbolic blow to the Malian junta, which is already under pressure following an alleged coup attempt. Farabougou is near the RN31 highway, which connects central and southern Mali via the northern parts of the Ségou and Koulikoro regions along the Mauritanian border. The capture of Farabougou will expand JNIM support zones along the Mauritanian border further into central and southern Mali, given that Malian forces used their base in the town to monitor cross-border trafficking networks and JNIM havens near the border.[28] JNIM can use these expanded and strengthened support zones to increase pressure on Nara, the district capital on the western end of the RN31. CTP has previously assessed that JNIM has conducted regular attacks on the other main road south of Nara since late 2023 to isolate the town by degrading the surrounding lines of communication.[29]

Farabougou is also symbolically important to the Malian junta. JNIM had besieged Farabougou in 2019 and the first half of 2020.[30] The Malian junta broke the siege and liberated the town in October 2020 as one of its first major military operations after taking power.[31] Malian junta leader Assimi Goïta visited the town following the campaign.[32] The loss of Farabougou five years later clearly undermines the junta’s narrative that it has improved the security situation in Mali.

The Malian junta arrested dozens of officials as part of an alleged coup plot in early August.[33] CTP and others have assessed that the arrests are likely related to internal power struggles and possible discontent with the deteriorating security situation.[34] Unconfirmed reports on X claim that Malian soldiers have refused to advance toward Farabougou without special forces reinforcements. Malian special forces are allegedly stationed near the capital protecting Malian junta leader Assimi Goïta, however, who originated in the special forces.[35]