Every crisis has a rhythm. Libya’s has moved from a low thrum of dysfunction to the pounding urgency of collapse. What once appeared as a fragile equilibrium held together by fragile oil revenues, a delicate foreign balance, and conflict fatigue is now clearly in disrepair. The fiscal figures are no longer deniable. The consequences are no longer distant. And the illusion of economic stability has ruptured.

For months, economists and analysts warned of this trajectory. Their forecasts were not based on abstract models but on daily observations: rising inflation, widening budget shortfalls, and the quiet disappearance of public oversight.

The Central Bank of Libya (CBL), long reticent, has now joined that chorus with a rare and public statement. Its warnings are stark: In 2024, the Government of National Unity spent over 109 billion Libyan dinars (LYD), while the parallel government in the east accrued more than forty-nine billion in off-budget obligations. Neither figure reflects coordination or restraint—just the actions of officials either ignorant of or indifferent to the consequences of unchecked spending.

Bracing for financial chaos

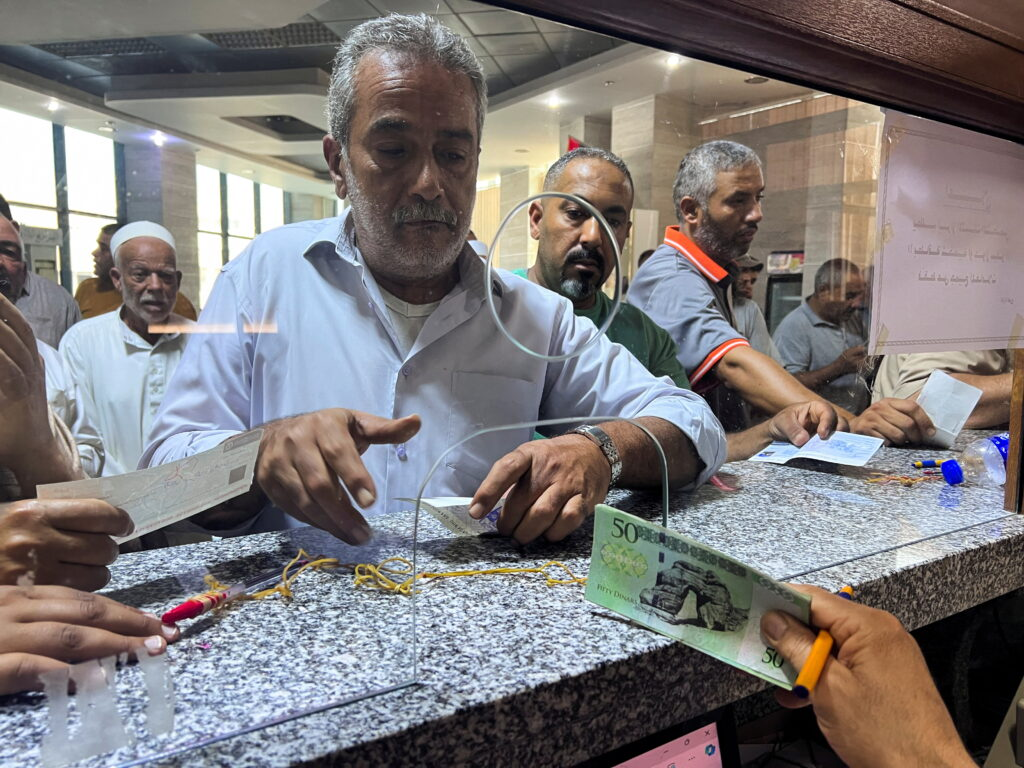

Both ledgers lay bare the scale of state capture and fiscal chaos. Alongside these warnings, the CBL also amended the official exchange rate, raising it to 5.48 LYD to the dollar while retaining its fifteen percent surcharge on foreign currency purchases. Framed as a technical adjustment, the move is a stopgap—an attempt to accommodate political excess within a shrinking monetary space. It underscores a deeper truth: Libya’s financial institutions are no longer guiding the economy. They are bracing against its unraveling.

Superficially, Libya still functions. Oil, at least in practice, is still exported. Salaries, though often late, are eventually deposited in the accounts of the country’s bloated public-sector employees.

But beneath the surface, the economy is disassembling. The black-market exchange rate has climbed to 7.8 LYD to the dollar within forty-eight hours of the CBL’s decree, a warranted vote of no confidence in Libya’s fiscal and monetary custodians. Institutions that once stabilized the system—through budgetary checks, revenue cycle audits, regulated foreign exchange, or centralized oversight—have been hollowed out or deactivated. What remains is an economy run on improvisation, backroom deals, and political convenience.

Looking back, the architecture of corruption has evolved in stages. First came the scramble for what Muammar Gaddafi had monopolized the allocation of: budget lines, salary schemes, and procurement deals. Later, transitional authorities waged fights over who wrote those allocations—to control the institutions and the budget pens. Today, that logic has culminated in the complete distortion of the allocation process itself. Libya’s economic crisis is no longer just about who benefits. It is about how benefit is manufactured.

An innovative system of corruption

Over the past several years, opaque and improvised mechanisms have steadily replaced formal revenue channels. At first, these workarounds were viewed as a tolerable compromise—a necessary price for preserving a fragile calm and avoiding renewed conflict. But what was once seen as a temporary accommodation has metastasized into a full-blown system of economic governance, one in which accountability is absent and discretion is unchecked. Crude-for-fuel barter deals, once framed as a pragmatic workaround, have become routine, sidestepping the national budget and brokered through opaque channels with no public oversight. They routinely bypass the national budget entirely and were often negotiated through informal brokers with transnational networks and no public scrutiny. Though the National Oil Corporation (NOC) has pledged to end crude-for-fuel swaps by March 2025, these deals are already being eclipsed by more elaborate and opaque arrangements—the latest evolution in Libya’s system of innovative corruption.

One of the most illustrative examples is Arkenu, a Benghazi-based company originally established for geological research but now repurposed as a vehicle for shadow oil exports. According to the United Nations Panel of Experts, Arkenu is operated by actors aligned with Libyan National Army (LNA) Commander Khalifa Haftar and serves as a financial conduit for eastern military and political interests. In 2024 alone, Arkenu independently exported approximately $460 million worth of crude oil under a GNU-approved deal, absent any transparent bidding, auditing, or publication of terms. As of 2025, it remains active—continuing to lift crude monthly from the National Oil Corporation—and sits at the center of an emerging system in which state-linked assets are repurposed to fund political actors outside formal channels.

The role of armed groups

Meanwhile, armed groups have entrenched themselves deeper into the infrastructure of Libya’s energy economy. In both east and west, militias have embedded themselves in utilities such as the General Electric Company of Libya (GECOL), where operational choices are influenced more by kleptocratic leverage than by institutional standards. Between 2022 and 2024, an estimated 1.125 million tons of diesel—allocated theoretically for power generation—were illicitly exported from Benghazi’s old harbor. These exports were facilitated through inflated supply requests issued via GECOL, the obstruction of audits, and threats of violence against oversight bodies.

The NOC, too, has been drawn into this vortex. Crony contracting has allowed politically connected firms to secure procurement deals and operational privileges, eroding the firewall between national resource management and elite patronage. This dynamic accelerated following the 2022 appointment of Farhat Bengdara as NOC chairman in a power-sharing arrangement between the GNU and eastern authorities. Though intended to ease executive tensions, the move entrenched political influence over the corporation’s operations. Bengdara’s abrupt resignation in early 2025 did not reverse this trajectory. Instead, his tenure left a lasting imprint: a politicized NOC, increasingly leveraged for factional gain rather than safeguarding Libya’s oil wealth.

This erosion of institutional neutrality has a fiscal analog in Libya’s monetary policy, where political imperatives now override sound economic management. At the core of the dysfunction lies the unchecked expansion of the money supply. Independent estimates suggest that the volume of money in circulation now exceeds 170 billion LYD—a level of liquidity that far outpaces productive output or revenue generation. But the deeper concern lies not in the quantity itself, but in how much of it has been manufactured ex nihilo.

Digital monetary creation—the injection of funds into the economy without any corresponding revenue or production—has become the fallback of a political order unwilling to curb spending or enforce discipline. The predictable result has been a cascading erosion of the LYD’s value, a surge in inflation, and a growing public mistrust in the state’s ability to steward its financial future. As foreign reserves shrink and black-market rates spike, Libya’s monetary system is no longer a stabilizing force; it is a mirror of its dysfunction. To call this mismanagement is too generous. This is structural predation, a system designed both to fail and extract. Public wealth is scarcely channeled into services or national development. It is captured, funneled through kleptocratic networks, and increasingly siphoned through untraceable contracts and offshore accounts.

Avenues of reform

Addressing this collapse requires more than fiscal prudence. It demands political realignment. Libya’s economic institutions must be recentered as sites of national governance, not tools of factional financing. The institutions that govern oil revenues, control disbursement, and oversee procurement must be protected, reformed, and in many cases rebuilt, not just with new laws, but with new incentives, protections, and public visibility.

A credible reform strategy must begin with mandatory public disclosure of all oil contracts, real-time publication of state spending, and a ban on off-budget arrangements. Procurement must be regulated through transparent, competitive systems. Revenue distribution must be guided by transparency, equity, and public oversight—not by decentralization for its own sake, nor by external stewardship. Reform must strengthen national institutions while ensuring that public funds reach intended sectors and communities through accountable, legally grounded mechanisms. These are not just technocratic ideals. They are prerequisites for legitimacy and recovery.

International actors—donors, multilateral institutions, and diplomatic envoys—must stop treating Libya’s economic collapse as a mere byproduct of its political fragmentation. Stability manufactured atop corruption is not stability at all. While much emphasis is placed on unifying the government, doing so without reforming its fiscal architecture would merely centralize corruption under a single executive. That may deliver temporary coherence, but it will not constitute progress. In fact, it risks consolidating the very networks that have driven economic ruin. Libya does need a single budget and a unified executive—but one subject to strict and enforceable guardrails on how public money is spent, disclosed, and audited. External engagement must support this principle. Anything less only subsidizes the continuation of state capture under a new administrative label.

Libya is not doomed to economic failure. But its current trajectory is unsustainable—not solely because the price of the oil barrel dropped, but because the political will to govern with integrity has long since evaporated. Recovery will require confrontation, not consensus. And it must begin with reclaiming the institutions that were designed to serve the public, not those who profit from its decline. Tinkering with technical levers like the exchange rate may buy time. But when such adjustments are used to sustain elite corruption rather than correct structural imbalances, they do not stabilize, they provoke. If this continues, the next phase of Libya’s crisis will not be quiet erosion. It will be public revolt.