SUMMARY

The government of Sudan is responsible for “ethnic cleansing” and crimes against humanity in Darfur, one of the world’s poorest and most inaccessible regions, on Sudan’s western border with Chad. The Sudanese government and the Arab “Janjaweed” militias it arms and supports have committed numerous attacks on the civilian populations of the African Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa ethnic groups. Government forces oversaw and directly participated in massacres, summary executions of civilians-including women and children – burnings of towns and villages, and the forcible depopulation of wide swathes of land long inhabited by the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa. The Janjaweed militias, Muslim like the African groups they attack, have destroyed mosques, killed Muslim religious leaders, and desecrated Qorans belonging to their enemies.

The government and its Janjaweed allies have killed thousands of Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa – often in cold blood, raped women, and destroyed villages, food stocks and other supplies essential to the civilian population. They have driven more than one million civilians, mostly farmers, into camps and settlements in Darfur where they live on the very edge of survival, hostage to Janjaweed abuses. More than 110,000 others have fled to neighbouring Chad but the vast majority of war victims remain trapped in Darfur.

This conflict has historical roots but escalated in February 2003, when two rebel groups, the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) drawn from members of the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa ethnic groups, demanded an end to chronic economic marginalization and sought power-sharing within the Arab-ruled Sudanese state. They also sought government action to end the abuses of their rivals, Arab pastoralists who were driven onto African farmlands by drought and desertification – and who had a nomadic tradition of armed militias.

The government has responded to this armed and political threat by targeting the civilian populations from which the rebels were drawn. It brazenly engaged in ethnic manipulation by organizing a military and political partnership with some Arab nomads comprising the Janjaweed; armed, trained, and organized them; and provided effective impunity for all crimes committed.

The government-Janjaweed partnership is characterized by joint attacks on civilians rather than on the rebel forces. These attacks are carried out by members of the Sudanese military and by Janjaweed wearing uniforms that are virtually indistinguishable from those of the army.

Although Janjaweed always outnumber regular soldiers, during attacks the government forces usually arrive first and leave last. In the words of one displaced villager, “They [the soldiers] see everything” that the Janjaweed are doing. “They come with them, they fight with them and they leave with them.”

The government-Janjaweed attacks are frequently supported by the Sudanese air force. Many assaults have decimated small farming communities, with death tolls sometimes approaching one hundred people. Most are unrecorded.

Human Rights Watch spent twenty-five days in and on the edges of West Darfur, documenting abuses in rural areas that were previously well-populated with Masalit and Fur farmers. Since August 2003, wide swathes of their homelands, among the most fertile in the region, have been burned and depopulated. With rare exceptions, the countryside is now emptied of its original Masalit and Fur inhabitants. Everything that can sustain and succour life – livestock, food stores, wells and pumps, blankets and clothing – has been looted or destroyed. Villages have been torched not randomly, but systematically – often not once, but twice.

The uncontrolled presence of Janjaweed in the burned countryside, and in burned and abandoned villages, has driven civilians into camps and settlements outside the larger towns, where the Janjaweed kill, rape, and pillage – even stealing emergency relief items – with impunity.

Despite international calls for investigations into allegations of gross human rights abuses, the government has responded by denying any abuses while attempting to manipulate and stem information leaks. It has limited reports from Darfur in the national press, restricted international media access, and has tried to obstruct the flow of refugees into Chad. Only after significant delays and international pressure, were two high-level UN assessment teams permitted to enter Darfur. The government has promised unhindered humanitarian access, but has failed to deliver. Instead, recent reports of government tampering with mass graves and other evidence suggest the government is fully aware of the immensity of its crimes and is now attempting to cover up any record.

With the rainy season starting in late May and the ensuing logistical difficulties exacerbated by Darfur’s poor roads and infrastructure, any international monitoring of the shaky April ceasefire and continuing human rights abuses, as well as access to humanitarian assistance, will become more difficult. The United States Agency for International Development has warned that unless the Sudanese government breaks with past practice and grants full and immediate humanitarian access, at least 100,000 war-affected civilians could die in Darfur from lack of food and from disease within the next twelve months.

The international community, which so far has been slow to exert all possible pressure on the Sudanese government to reverse the ethnic cleansing and end the associated crimes against humanity it has carried out, must act now. The UN Security Council, in particular, should take urgent measures to ensure the protection of civilians, provide for the unrestricted delivery of humanitarian assistance and reverse ethnic cleansing in Darfur. It will soon be too late.

SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS

To the Government of Sudan

Government forces and government-supported Janjaweed militias must immediately cease their campaign of ethnic cleansing and attacks on civilians and civilian property in Darfur.

Immediately disarm and disband the Janjaweed militias in Darfur and withdraw them from those parts of Darfur they have occupied from 2003 to the present.

Conduct prompt, impartial and independent investigations of abuses by the Janjaweed militia forces and the Sudanese armed forces in Darfur, prosecute alleged perpetrators in accordance with international fair trial standards, and provide reparations for the victims of such abuses, including by recovering and returning all looted property.To the Government of Sudan and the opposition Sudanese Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM)

Facilitate the full, safe and unimpeded access of humanitarian personnel and the urgent delivery of humanitarian assistance to all populations in need in Darfur.

Take immediate and effective measures to enable the voluntary return of refugees and displaced persons to their homes in safety and dignity.

Facilitate the establishment of, and cooperate with, a U.N. human rights monitoring mission, and an international Commission of Experts to investigate and reach conclusions on the evidence concerning crimes against humanity, war crimes, and other violations of international humanitarian law committed by all parties in Darfur in 2003-2004.To the members of the U. N. Security Council

Take measures, including through the adoption of a resolution, that seek to end and reverse "ethnic cleansing" in Darfur, ensure the protection of civilians at risk, create an environment conducive to the voluntary return in safety and dignity of all refugees and displaced persons, and provide for the effective and unrestricted delivery of humanitarian assistance.

Establish an impartial Commission of Experts to investigate and reach conclusions on the evidence concerning crimes against humanity, war crimes and other violations of international humanitarian law committed by all parties in Darfur in 2003-2004.

Establish an international human rights monitoring mission with field offices in Darfur and Khartoum mandated to periodically publicly report on human rights and humanitarian law violations.To the African Union

Rapidly deploy the Ceasefire Commission and ceasefire observers to Darfur and ensure that adequate numbers of observers are deployed before the start of the rainy season.

Ensure that ceasefire observers periodically publicly report on all violations of the ceasefire agreement including the parties' compliance with international humanitarian law.

Monitor access to, and the provision of, humanitarian assistance to war-affected civilians.To U.N. member states

Contribute personnel, equipment, other resources and funding to the African Union ceasefire monitoring mission.

Contribute to the economic and social reconstruction of Darfur and support international humanitarian assistance and human rights monitoring and investigations in Darfur.To U.N. humanitarian agencies and humanitarian nongovernmental organizations

Promote the protection of civilians simultaneous with the distribution of humanitarian assistance; decentralize aid distribution rather than concentrate it in displaced camps and settlements, to the greatest extent possible within security limits.

Make efforts to prevent the creation of permanent displaced persons camps that reinforce the ethnic cleansing and forced displacement that has occurred.Complete recommendations appear near the end of the report.

BACKGROUND

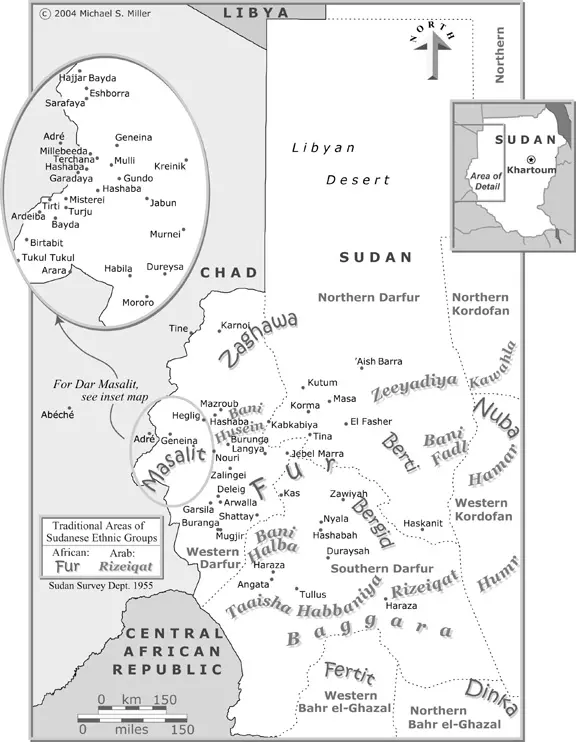

Darfur is Sudan’s largest region, on its western border with Libya, Chad, and the Central African Republic. Darfur has been divided into South, West, and North since 1994. The predominant ethnic groups of West Darfur are the Masalit and Fur, who have often united in marriage with Arabs and other Africans.1

West Darfur, with a population of more than 1.7 million,2 is ethnically mixed although African groups predominate: in Geneina and Habila provinces the Masalit are the majority (60 percent), followed by the Arabs and other Africans, namely, Zaghawa, Erenga, Gimr, Dajo, Borgo and Fur. In Zalingei, Jebel Marra, and Wadi Salih provinces the Fur predominate. In Kulbus province approximately 50 percent is Gimr, 30 percent Erenga, 15 percent Zaghawa, and 5 percent Arab. Together the Fur and the Masalit comprise the majority of the population of West Darfur. Dar Masalit, or homeland of the Masalit,3 is located around Geneina – the state capital – and north and south along the border.

The Masalit, Fur, and other sedentary African farmers in Darfur have a history of clashes over land with pastoralists from Arab tribes, primarily the camel- and cattle-herding Beni Hussein from the Kabkabiya area of North Darfur and the Beni Halba of South Darfur. Until the 1970s, these tensions were kept under control by traditional conflict resolution mechanisms underpinned by laws inherited from the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium (1898-1956). While clashes over resources took place, they were usually resolved through negotiations between community leaders.4 It is not the case, as the Sudanese government maintains, that the current violence is merely a prolongation of the predominantly economic tribal conflicts that have always existed in the region.

In recent decades, a combination of extended periods of drought; competition for dwindling resources; the lack of good governance and democracy; and easy availability of guns have made local clashes increasingly bloody and politicized. 5 A wide-reaching 1994 administrative reorganization by the government of President Omar El Bashir in Darfur gave members of Arab ethnic groups new positions of power, which the Masalit, like their Fur and Zaghawa neighbors, saw as an attempt to undermine their traditional leadership role and the power of their communities in their homeland.6

Communal hostilities broke out in West Darfur among other places in 1998 and 1999 when Arab nomads began moving south with their flocks earlier than usual.7 During the 1998 clashes, more than sixty Masalit villages were burned, one Arab village was burned, approximately sixty-nine Masalit and eleven Arabs were killed, and more than 5,000 Masalit were displaced, most fleeing either into Geneina town or to Chad. Despite an agreement for compensation for both sides negotiated by local tribal leaders,8 clashes resumed in 1999 when nomadic herdsmen again moved south earlier than usual.

These 1999 clashes were even bloodier, with more than 125 Masalit villages partially or totally burned or evacuated and many hundred people killed, including a number of Arab tribal chiefs. The government brought in military forces in an attempt to quell the violence and appointed a military man responsible for security overall, with the power to overrule even the West Darfur state governor. A reconciliation conference held in 1999 agreed on compensation for Masalit and Arab losses.9 Many Masalit intellectuals and notables were arrested, imprisoned, and tortured in the towns as government-supported Arab militias began to attack Masalit villages; a number of Arab chiefs and civilians were also killed in these clashes. The barometer of violence crept steadily upward.

ABUSES BY THE GOVERNMENT-JANJAWEED IN WEST DARFUR

Since the SLA attack on Fasher in April 2003, and particularly since the escalation of the conflict in mid-2003, the government of Sudan has pursued a military strategy that has deliberately targeted civilians from the same ethnic groups as the rebels.

Together the government and Arab Janjaweed militias targeted the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa through a combination of indiscriminate and deliberate aerial bombardment, denial of access to humanitarian assistance, and scorched-earth tactics that displaced hundreds of thousands of civilians.10 Government forces also regularly arbitrarily detained and sometimes tortured Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit students, political activists, and other individuals in Darfur and Khartoum suspected of having any allegiance to the rebel movements.

Mass Killings By the Government and Janjaweed

Human Rights Watch’s March-April investigations uncovered large-scale killings in fourteen incidents in Dar Masalit alone in which more than 770 civilians perished between September 2003 and late-February 2004. These are not the only incidents that occurred in Dar Masalit during those six months, but rather those which Human Rights Watch was able to corroborate with testimony from witnesses and other credible sources. Human Rights Watch obtained further information from witnesses to mass executions in the Fur areas of Wadi Salih province in the period from November 2003 through April 2004. Although this information is also far from complete given the difficulty of access to victims living in government-controlled towns and camps for the displaced, it indicates that the attacks on Masalit and Fur villages often follow a similar pattern.

Attacks and massacres in Dar Masalit

All fourteen incidents in Dar Masalit involved coordinated attacks by the army and Janjaweed. Four were conducted with prior air attacks – starting in late December 2003. In two incidents prior to late December, helicopters lifted supplies and/or troops into the area before the attacks. In five of the incidents, a location was subjected to attack more than once. At least six of the fourteen incidents involved clusters of villages, up to thirty in one example.

From mid-2003, attacks on villages rather than rebel positions have been the norm rather than the exception. While many of the bigger villages have self-defense units – first set up in the 1990s to give a measure of protection against Arab raiders – many have had little or no armed presence at all. The SLA in Dar Masalit, at least when Human Rights Watch visited, did not base armed men in villages; they were hidden under outcroppings of rocks and in ravines. In several instances when the rebels attempted to intervene in attacks on Masalit farming communities, they arrived too late to prevent destruction and death. On other occasions, the reported presence of rebels in a market has been sufficient to trigger an attack.

The majority of the victims in the Masalit attacks documented by Human Rights Watch have been men. This would seem to be because villages in the path of mobilized government and Janjaweed forces have been alerted by friends, relatives, and tribal kinfolk, who have sent runners to give warning. Women and children have been sent away – by donkey to Chad or the nearest town, when time was on their side; by foot, to nearby valleys where trees and rocks might provide cover, when it was not.

In most of these attacks, shooting by government and Janjaweed appeared to be targeted at the civilian population. Fatalities in all but the smallest villages are almost always in double figures – rising as high as eighty in the most extreme cases. The number of deaths is alarming as the villages attacked seldom have more than a few hundred inhabitants. It is likely, moreover, that the death toll resulting from these attacks has risen, unrecorded, in the days and weeks after the attacks as wounds, disease, and the hardships of displacement took their inevitable toll.

Massacres or mass killings of civilians in Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa areas have taken three forms: extrajudicial executions of men, by army and Janjaweed; attacks in which government soldiers and Janjaweed have played an equal role, fighting side by side; and attacks in which government forces have played a supporting role to Janjaweed – “softening up” villages with heavier weapons than those carried by the Janjaweed, providing logistical support and, in the opinion of many villagers interviewed, “giving the Janjaweed protection as they leave.”11

Janjaweed always outnumber government soldiers, but arrive with them and leave with them. It is not clear which force is the commanding force. It is clear that the Janjaweed are not restrained, in any way, by the uniformed government forces who accompany them in army cars and trucks.

The following reports of mass killings are based on the testimonies of civilians who were displaced from the villages concerned and who spoke to Human Rights Watch in March and April 2004.12 These reports are necessarily incomplete. The dispersal of communities, and the difficulty of getting detailed information from government-controlled towns and displaced camps, makes investigation difficult.

- Mororo village, close to the Masalit-Fur border: forty dead

On August 30, 2003, soldiers and Janjaweed attacked and burned Mororo, stealing cattle and killing sixteen people. They returned the following day and killed twenty-four more people, all young men since women and children had already run away. One of the attackers’ leaders reportedly shouted: “We must get these people out of this place!”

The village’s self-defence group was reportedly very small and could offer no resistance.

In the following weeks, a few villagers returned and built rough shelters. But in November a large force of Janjaweed and army returned and burned the village for a second time, killing a blind man. The village was again abandoned. 13

- The Murnei area, twelve villages: eighty-two dead

On October 9, 2003, soldiers and Janjaweed attacked twelve villages in the Murnei area – Dingo, Koroma, Warai, Hydra, Andru, Zabuni, Taranka, Surtunu, Narjiba, Dureysa, Langa and Fojo – killing eighty-two people including women, children, and worshippers in a mosque, according to reports collected by local leaders. Jumaa, a twenty-two-year-old farmer from the village of Gokur, visiting relatives in the area at the time, said it was raining hard and even the soldiers were on horseback.

They encircled the village. I hid in the grass and heard the commander saying over his Thuraya [satellite phone]: ‘We are near the village no. 1541. We found the self-defense groups and killed them.’ They burned everything, looted everything. They burned all the mosques that were not made of bricks. The Janjaweed took girls into the grass and raped them there – in Dingo and Koroma. They raped thirteen including eighteen-year-old Khadija.14

Jumaa said some of the villages had self-defence units, but they were independent of the SLA and were purely defensive. “The SLA was nowhere near,” he said. “They were in the mountains. The government is not after the SLA. They want to put Arabs in the villages.”15

Jumaa said the area was burned for a second time in December.

- Mango, in the Terbeba-Arara area: at least twenty killed

In November 2003, Janjaweed attacked at least four villages close to Mango – Angar, Bayda, Nyorongta and Shushta – and remained in the villages after burning them. Izhaq, a forty-two-year-old farmer from Mango Gobe, said helicopter gunships also landed in the area. “No one was allowed anywhere near the area before the helicopters came,” he said. “We think they were bringing weapons. Two or three days later they attacked Mango.”16

In just one village in the Mango cluster, Mango Buratta, soldiers and Janjaweed killed twenty people.17 Adam , a forty-one-year-old farmer, said they stole all the cattle in the village and burned the entire village. “On that same day, they attacked eleven villages,” he said. “Not a single home was left. Antonovs and helicopters came the next day. Why? How can we know? To see if anyone was left, I suppose. They didn’t bomb.” 18

Sherif, a thirty-five-year-old farmer, said villagers managed to bury the dead in the night, before the airplanes came. They then went to Chad, with no possessions, finally driven out by the combination of government and Janjaweed forces.

It took ten hours walking. We lost all our cattle. We have no grain or sesame or groundnuts. The problem began around 1997 with the Arab nomads. It wasn’t Janjaweed and government soldiers [then], like this [is now]. Now the government has many helicopters.19

- Urum, near Habila: 112 killed in two attacks

Urum, which became a centre for Masalit civilians displaced from nearby villages, was attacked twice. “Why did they kill so many people in Urum – 122 in two attacks over a month? I don’t know. But many villages were burned before Urum and the civilians were in Urum. The villages burned included Gororg, Dureysa, Tirja, Maliam, Mororo, Gorra and Korkojok,” said thirty-seven-year-old Ahmad, a former Urum resident.20

On the first occasion, in November 2003, eyewitnesses reported that Janjaweed came without the army and burnt eighty of 300 huts. They took 3,000 head of cattle and killed forty-two men, most of them young men.

“There was a funeral that day for an eighty-year-old man, Yahya Abdul Karim, and people were in the mosque reading funeral prayers for him,” said eyewitness Ahmad. “Sixteen of the forty-two were killed in the mosque.” 21 The imam and his three-year-old grandson were killed, then the attackers chased after others fleeing and shot them down as well.

The imam, Yahya Warshal, ran from the mosque to his home to get his three-year-old grandson, who was an orphan. The Janjaweed followed him and killed him and the child. The youth of the village didn’t fight. They were running to save themselves. The Janjaweed galloped after them and killed them. More than 3,000 cows were stolen and goats and sheep, horses and donkeys. The Janjaweed wore khaki – the same as the army.22

A second, joint attack by army and Janjaweed followed in the first week of December – variously reported as December, 6 or 7, 2003. The Janjaweed returned, this time with the army, at 6:00 a.m. Eighty people, including women and children, were killed in the second attack, which lasted four days while the army watched.

The soldiers were in Land Cruisers with doschkas mounted on them. They had one lorry too. The Janjaweed came on horses and camels. The government stayed on the edge of the village. The Janjaweed went in and killed eighty people including women and children in a four-day period. The army saw everything.

“I went back at night and stayed for three days. Bodies were everywhere. I buried twenty-three people. But the Janjaweed returned after four days,” 23 said Ahmad.

- The Bareh area, east of Geneina: 111 killed

In three villages in the Bareh area – Arey, Haskanita and Terchana – Janjaweed accompanied by three car-loads of soldiers killed 111 people in one day, December 11, 2003, according to survivors. Village leaders said the villages had 485 huts in all – 80, 200, and 205 respectively – and suffered twenty-three, thirty-five and fifty-three dead respectively. The dead included twenty-three women and a one hundred-year-old man, Barra Younis, from Terchana.

“Barra Younis couldn’t walk and the Janjaweed burned him alive in his hut,” said a forty-two-year-old Terchana man, Adam. “They saw him there and they burned him.”24

Adam said the attack began at 9:00 a..m. The joint forces surrounded the village and killed fifty-two people as they were running away.

They took the cattle and burned all the village. They took some food for their horses and burned the rest. Helicopters came when we were burying the bodies, right after the attack. They were flying low. We could see the pilot. He was only wearing a vest. He killed a woman – seventy-year-old Mariam Abdul Qadar – and a horse. The Janjaweed were wearing uniforms, with stripes on the shoulders.25

This witness said villagers did not resist because the presence of army cars told them the attack was more serious than a cattle raid.

The Arab nomads never came with cars and helicopters. This is not Arab nomads. This is the government. We had a self-defense unit, but when we saw the cars we said ‘This is the government’ and we ran. We didn’t fight. The government doesn’t like black people. We didn’t complain to the police. The police are near us in Kreinik and did nothing. We all left the village and went to Geneina and Chad.26

- Habila Canare, twenty-five kilometers east of El Geneina: fifty killed

On December 20, 2003, government soldiers and Janjaweed surrounded the village at 6:00 a.m. An hour later, according to eyewitnesses, three helicopter gunships landed in the village and soldiers got out. Then the soldiers and Janjaweed who had been waiting outside the village came in. They were wearing identical uniforms but for the fact that the soldiers’ were a darker shade of green. The attack left approximately fifty people dead – including fifteen women, ten children and a Masalit policeman – in a population estimated approximately 500 (seventy-three huts). Some were killed as they were running away; some were shot dead inside their huts. The attackers took all the guns from the police station and also its zinc roof. The Janjaweed took the cattle and left. The soldiers then burned the village. 27

- Kondoli, in the Misterei area: twenty-four killed

Villagers from the Misterei area said Janjaweed moved into Misterei at the end of 2003. One witness, Nureddine, a twenty-eight-year-old former policeman, said they came from Geneina, in nine army cars, and brought their own food. “They came in two groups,” he said. “One group joined the army post and the other the police post. They patrolled by themselves in the bush for a week.” 28

Soon after this, on December 28, 2003, soldiers and Janjaweed killed twenty-four people including five women – including Khamisa Haroun, forty-seven; Shama Adam, thirty-three, Mariam Khamis, twenty-five, and Ijela Mohammed, thirty-eight – in the village of Kondoli, a few miles outside Misterei. Kondoli, with 150 huts, had a population of about 1,000 people. Yayha, a thirty-two-year-old farmer, said army and Janjaweed had moved into the village the previous day, December 27.

“We were afraid and wanted to run away,” he said, “but they said: ‘No, no. We don’t want to hurt you. We are the government. Don’t be afraid. We are coming to save you.'” The 400 Janjaweed “protectors” made a place for themselves on the eastern side of the village. The next day they attacked Kondoli, shooting a three-year-old child at point blank range, while making racial epithets:

They came into Kondoli saying: 'Kill the Nuba! Kill the Nuba!' They shot a child who was lying on the ground because he was afraid. They said: 'Get up so we can see you.' But he was afraid. So they shot him. He was called Maji Gumr Zahkariah and he was three years old.29The survivors fled to Chad, four hours away. “They took everything and burned the entire village…. We can’t go back at night to get food because Janjaweed are on the road.” 30

- Nouri, near Murnei: 136 killed

Nouri, a large area of several villages comprising 900-1,000 huts, or about 7,000 people, was attacked by Janjaweed and army on December 29, 2003. Villagers interviewed separately said about 170 villagers were killed in twenty-four hours. They said two helicopter gunships rocketed the area before ground forces arrived. They were flying so low that people in the largest village, Nouri Jallo, could see the pilot.

“People were very afraid because they had never seen them [helicopters] before,” said a former police officer, Ali. “They said they were flying so low that if you threw something, you could hit them.”31

Mohammed, a thirty-year-old doctor from the area, said three Land Cruisers carrying soldiers and many Janjaweed came to the police station in Nouri Jallo before the attack and asked about the SLA. The police replied: “We don’t have any. Really we don’t.” Then, Dr. Mohammed said, the attackers burned the village and killed seventy-five people including five women. “Most of the dead were men because women and children stayed [hidden] in the huts.”32

In the largest village, Nouri Jebel, forty-six bodies were counted including seven or eight children. The attackers made off with the zinc roof off the village school.

In Nouri Heglig, where there were sixty-four huts, the attack began at 7:30 a.m. Feisal, a twenty-seven-year-old farmer, said that the army and the Janjaweed all wore the same uniforms when they entered the village:

The army was in Land Cruisers and the Janjaweed on horses and camels.... The Janjaweed entered the village first, followed by the cars. They were shooting indiscriminately. They went into tukls [huts] and killed people who were hiding under their beds.33Feisal said seven villagers were killed. “People went to bury them,” he said, “but the Janjaweed and army came back to burn the village. They burned everything. Not a single tukl was left. The people only had time to cover the bodies with grass because of the heat. The soldiers and the Janjaweed burned the bodies … “34

The Nouri area was attacked a second time, on February 10, 2004. People had returned to the area because they had been told by local government officials in Murnei and Sissi that they should.

“At 10:00 a.m., one helicopter gunship arrived, flying low, followed by Janjaweed in front and Land Cruisers behind,” said Dr. Mohammed. “They burned the entire village and killed thirty-eight including four men who were praying in the mosque. We formed a self-defense group in 1996 and a lot of them were killed on that day. Most had only Kalashnikovs [assault rifles]. They had no link to the SLA. The SLA forces are very far away. The SLA doesn’t put soldiers in the villages. They don’t have enough.”35

- Kenyu, near Forbranga: fifty-seven killed

Villagers told Human Rights Watch that Kenyu was attacked twice within a month. On the first occasion, in December 2003, people were awake and fought the attackers off. On the second, in January 2004, people were asleep when Janjaweed and army Land Cruisers approached, at dawn, from two directions – from the east and from the west – and soldiers began shooting with heavy weapons including rocket-propelled grenades. Fifty-seven people – including the village imam – were reported killed in a population of about 3,500 (500 huts.)

“People ran without their children because there were so many bullets,” said twenty-two-year-old Adam, who subsequently joined the SLA.36 “They could not stop to pick them all up. So many children were killed. Everything was burned. On the same day they burned Buranga. They looted but did not burn Suju.”37

- Sildi, south-east of Geneina: twelve killed

Sildi was attacked, first by air and then by land, on February 7, 2004. Abdul, a forty-two-year-old farmer, said two Antonovs bombed first, destroying two huts and sending women and children running for shelter in the hills.

“Then the Janjaweed and the government came,” he said. Twelve were killed in the village, then it was burned. Some were killed point-blank.

They killed twelve people including two women. The women were Asha Adam, sixty, who was killed in her home, and Arba Mohammed, forty. She was told to bring the water for the soldiers, but refused. The Janjaweed killed her. They burned all the village and we came to Chad.38

Both the Janjaweed and the government came into the village and shot the villagers.

This witness could tell the difference between the Janjaweed and the army soldiers only because of insignia on the uniforms.

The Janjaweed have a horse on their pockets and the soldiers don’t. The leader of the Janjaweed has stripes on his shoulders, just as they do in the army. 39

Another farmer, forty-year-old Ahmad, said he saw only one Antonov – at 8:00 a.m. “At 9:00 am,” he said, “the Janjaweed came with horses and camels and behind them the army with cars.”40 In the next few days, thirty villages of Sildi were looted and burned: the number of dead is not known.

- Tunfuka, south of Murnei: twenty-six killed

Tunfuka was attacked, by air and land, on February 7, 2004, killing at least twenty-six people, according to villagers now in Chad. Izhaq, a twenty-four-year-old farmer, said two Antonovs bombed for an hour and killed eight people – including three men, three children and two old women. He said seven camels and thirteen cows were killed, and the village began to burn.41

The army arrived in vehicles and the Janjaweed followed an hour later, shouting racial abuse, shooting eighteen people dead and looting the cattle, according to this witness:

Then seven army Land Cruisers came. The Janjaweed arrived an hour later. They burned the village, rounded up the cattle and shot people who were running away. They killed eighteen people. Then the Janjaweed left with the cattle followed by the government. The Janjaweed were shouting: 'Kill the Nuba!'42This Tunfuka farmer, was hiding in the grass only thirty meters from the huts, identified the Janjaweed commander by name: “Abdullah Sheneibat was the one giving orders,” he said.

.He had a pistol and a beige car. It was the same as the army’s cars except army cars are green. He got out of his car and was giving orders to the soldiers and the Janjaweed. He left with the soldiers. Two government cars went first, then Sheneibat, then another car.43

Following the hour-long bombing, village burning, and ground attack by Janjaweed and soldiers killing twenty-six, the survivors fled to Chad.

- Tullus: at least twenty-seven killed

On February 10, 2004, Antonov planes bombed the village of Tullus in advance of an attack on the village by Janjaweed. Most women and children managed to leave the village before the Janjaweed arrived. They were warned of the approach, according to forty-two-year-old Kaltoum, but the Janjaweed went looking for them where they were hiding in the mountains:

We were told by someone in Murnei that the Janjaweed were coming, so we left the village and ran to the mountains. Only the Janjaweed burned the village. But after that the Janjaweed came with the army looking for civilians in the mountains about a mile away. The army had cars. Some of them were on foot. 44One villager, Hassan, said at least twelve men were killed in the village; other sources put the figure as high as twenty-three. Fifteen people including seven women and six children were reportedly killed outside the village – some of them targeted and then shot in cold blood.45

Hussein, twelve, was hiding away from the village, behind a tree with three other children, when Janjaweed and soldiers shot him three times – in the face, right arm and right leg. Three other children hiding with him were injured at the same time:

I was in a valley near the mountains. I saw many Janjaweed and soldiers coming. They shot me from that far (gesturing to a tree about twenty yards away) and I fell down. They saw me and aimed at me. I was hiding behind that tree with three other children – Yassin (twelve), Manyo (nine); and Fatima (seven). I saw them all fall down [injured].... I saw three people dead in that valley, including a woman – Gaisma Mohammed Yousif (eighteen).46Hussein said he did not know who shot him. “They were all wearing uniforms,” he said. They were certainly close enough to see that he was not a full-grown man. “Before they shot me they said: ‘You are Tora Bora'” – a reference to the Afghan mountains where Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda fighters operate and a phrase often used by Janjaweed to refer to SLA rebels. “Then they took the cows and left me alone. There are no Tora Bora in Tullus. It’s a village.”47

Hussein’s father wrapped him in a blanket and took him on a donkey to Dwelem, some twenty-five miles away, and then to Chad. The three other children were taken by their families to the town of Murnei. In the words of Hussein: “They saw us, they aimed at us, and they shot us.”48

- Terbeba: twenty-six killed

Terbeba was attacked by army and Janjaweed on February 15, 2004, at 6:00 a.m. The village headman, Abdullah, forty-nine, said these forces killed thirty-one people49 including old men and women and five members of the SLA who arrived to try to defend the village two hours after the attack began.50

“There were more than 500 families in Terbeba,” he said. “We grew potatoes, cucumbers, beans, millet.” Against the 500 families and eight Masalit policemen were 300 mounted Janjaweed accompanied by four government cars with soldiers:

The attack was done by some 300 Janjaweed on horses and camels, accompanied by four government cars – three Land Cruisers carrying soldiers and a Renault for logistics [ammunition]. The Janjaweed were shouting: 'Kill all the Nuba!' About 90 percent of them were wearing army uniforms and the rest were in ordinary clothes.51The SLA arrived after two hours, and together with the eight Masalit policemen in the police station put up resistance. “The police shot,” Sheikh Abdullah said, “but were useless. The attackers burned the police station too.” The army participated in the burning and looting as well. From beginning to end, the fighting lasted for eleven hours.

The army burned houses, stole 1,000 cattle, stole some grain and burned the rest. They stole our horses and used them for burning, stealing and killing…. They hit women 52

In addition to hitting women, the attackers burned one of two mosques and tore up the Qorans in both, according to the headman.

- Millebeeda village and area, south-west of Geneina: fifty-nine civilians killed

On February 17, 2004, according to the local tribal leader or omda, thirty-seven-year-old Musa, government soldiers with “big guns” – doskhkas and rocket-propelled grenades – attacked Millebeeda village together with Janjaweed.53 Musa had left the village fifteen minutes before the attack and did not witness it. But he quoted villagers as saying “they all wore one uniform”. He said thirty-one villagers were killed including four women, three children and a Masalit rebel fighter, twenty-seven-year-old Ibrahim Ismael.54 According to a villager, someone from nearby Misterei sent warning of the attack, saying: “‘The Janjaweed may attack in the next few days because they say the SLA is in the village.'”55

The coordinated attack was conducted by hundreds of army soldiers and Janjaweed who descended on the village from three directions. A villager who witnessed the attack, thirty-year-old Bukhari., said hundreds of Janjaweed and government soldiers came in three groups from the north, south and east with camels and horses. 56

“When they came into the village,” Bukhari said, “they began shooting people. I saw my uncle Arbar, forty-five, leave his house, unarmed, and run away. They shot him from 200 yards. He had four children. Then the police began to resist – there were only seven or eight of them, but they were all Africans – and I succeeded in escaping with my wife and two-year-old son.”57

Mass Executions of captured Fur men in Wadi Salih: 145 killed

On March 5, 2004, government and Janjaweed forces executed at least 145 men belonging to the Fur tribe in Wadi Salih, one of West Darfur state’s six provinces. The men were killed on the same day in different places – nine Fur chiefs in prisons in Mugjir and Garsila, where they had been taken a week earlier,58 seventy-one captured Fur men in a valley south of Deleig, and another sixty-five captured men in a valley in the Mugjir area west of Deleig. 59

The men executed in the valley south of Deleig were part of a larger group rounded up in a number of villages earlier in the day, after being asked their villages of origin. Witnesses said the government and Janjaweed were singling out men displaced from villages that had been previously burned – with special emphasis on the Zamey area south of Deleig.

The mass executions in Wadi Salih, one of the gateways to the SLA’s headquarters in the Jebel Marra mountains, may have been in retaliation for an SLA attack on government troops in the Mugjir area of the province a month earlier, on February 1, in which the SLA says it killed more than one hundred government soldiers.

A survivor of one of the mass killings, a farmer who was shot in the back rather than the neck, told a neighbor that the arrested men were taken, in army trucks and cars, to a valley a few miles south of Deleig. “Then they lined us up, made us kneel down and bend our heads – and shot us from behind,” he told a neighbor. “I was left for dead … ” The executioners were army soldiers and Janjaweed, operating together.60

The neighbor, who can be identified only as Abdul,61 said people in the heart of the Wadi Salih area woke up on March 5 to find the whole area surrounded by government soldiers and Janjaweed commanded by Ali Kwoshib. Kwoshib reportedly established a Janjaweed base in Garsila in July 2003 and, after being given 1,500 automatic rifles by the army, burned a large area of Wadi Salih. “Dozens of villages around Deleig have been burned by the government and many people had fled to Wadi Salih,” he said. 62

A similar hunt for men displaced from the burned villages took place in other areas of Wadi Salih. “The government and Janjaweed came and asked men aged between twenty and sixty where they came from. If they were displaced they took them to the police station.”63

On or about the same day as the massacre south of Deleig, March 5, 2004, dozens of these detained men were taken from the police station to a place “south of Wadi Salih [where] there is a hill and near that hill a valley. They killed seventy-one men there that evening … It happened in Mugjur just like it happened in Deleig. They took them to the hills and killed them there,” he said.

Other Mass Killings of Fur civilians in Wadi Salih

In August 2003, Fur villages in Mukjar and Bindisi districts were attacked by Janjaweed and government forces who looted the villages and killed civilians, sometimes after SLA attacks in the area.

The SLA attacked Bindisi town, one of the larger towns in rural West Darfur, with an estimated population of 16,000, in early August. SLA forces looted the police station of ammunition and machine guns, killed two people including an Arab detainee in the police station and abducted a businessman.

Within a week, police came to Bindisi and a nearby village called Kudung in the early morning and told the population that the “Janjaweed were coming but that nobody should clash with them and all should remain in their houses.” One witness from Bindisi said that the policemen came with a letter from the commissioner of Garsila (now the Minister of Health for West Darfur) stating that the Janjaweed were coming to “collect their share of the zakat” or Islamic tax.64

Both Bindisi and Kudung were partly burned and destroyed and forty-seven people were killed in the attack. The market and shops were totally looted, and most of the loot was carried away on camel and horseback.

Kudung was revisited by the Janjaweed in the early morning several weeks later and the rest of the village was destroyed. More people were killed, including one child and an old woman who burned to death in her house. 65

The attacks described above are clearly only a fraction of the total number of attacks on civilians and villages in the Wadi Salih area, particularly since there have been further attacks in 2004.

Aerial bombardment of civilians

The government of Sudan has made extensive use of attack aircraft – mainly Antonov supply planes dropping crude but lethal “barrel bombs” filled with metal shards, but also helicopter gunships and MiG jet fighters – in many areas of Darfur inhabited by Masalit, Fur, and Zaghawa civilians.66 It has bombed not only villages, but also some towns where the displaced have congregated.

Significantly, Antonov bombing has seldom been used along the southern part of the international border with Chad, although there has been significant bombing north around Tine and Kulbus, where two rebel groups have had a presence. In border areas of Dar Masalit, helicopters and Antonov planes have however, often been used for reconnaissance, both before and after attacks.

Tunfuka was bombed by two Antonovs on February 7, 2004, killing eight people including Abdo Mohammed, An-Nur Mohammed Zein, Adam Mohammed Idriss, Khadija Mohammed and Asha Yaacoub. A twenty-eight-year-old villager, who witnessed the bombardment, Izhaq, said the Antonovs returned the following day, but did not bomb. He surmised this was because the village had been completely destroyed.67

But the most lethal confirmed case of aerial bombardment occurred in the town on Habila on August 27, 2003. Habila was at the time packed with civilians displaced from villages that had already been cleared – among them, Urum, Tunfuka, Tullus, Andanga and Hajjar Bayda.

Jamal, a thirty-year-old lawyer, was in Habila at the time visiting family. He said twenty-four people – all civilians – died in the bombardments, including four of his own relatives: his brother Mustafa, twenty-seven; sister Sadiya, twenty-five; and two nephews, Safa, seven, and Mada, four. Five other relatives were wounded – his mother Jimhia, two brothers and two nephews.68

“Antonovs bombed Habila six times that day,” he said. “Twenty-four people were killed. All were civilians.” The residents surmised that Habila was so extensively bombed despite the presence of police and army because it was full of displaced people.

There are many questions about this bombing: there were police in Habila, and army. The police were Masalit, but the army was mixed – Masalit and Arabs. Habila was full of displaced. We think the bombing was because of the displaced. 69

Gunships have been used to reconnoitre villages in advance of ground attacks. On January 5, 2004, a single helicopter gunship flew over Korkoria village, near Geneina. Omar, a thirty-one-year-old farmer, said the gunship was flying at hut-level – suggesting it was not expecting any ground fire. He said it did not bomb. The next day, however, a group of approximately 150 Janjaweed attacked Korkoria, killing four people and leaving only one hut unburned.70

Gunships have also been used to reconnoitre villages immediately after they have been burned and attacked – arriving within one to three days of the initial attacks, according to villagers. Sheikh Abdullah of Terbeba said gunships and Antonovs flew over Terbeba three or four days after the village was destroyed. “They did not bomb,” he said. “We think they were looking – to see what was there and to make sure the village was empty.” It was the same in Millebeeda, close to the border with Chad: Antonovs flew over three days after the attack, according to Omda Musa. Millebeeda, too, was deserted.71

Systematic Targeting of Marsali and Fur, Burnings of Marsalit Villages and Destruction of Food Stocks and Other Essential Items

Human Rights Watch research in Darfur in March and April 2004 confirmed reports from refugees in Chad and other sources that Sudanese government forces and Janjaweed have systematically attacked and destroyed villages, food stocks, water sources and other items essential for the survival of Fur and Masalit villagers in large parts of West Darfur.72

Villages were not attacked at random, but were emptied across wide areas in operations that reportedly lasted for several days or were repeated several times until the population was finally driven away. Many civilians were killed in the course of these attacks as described in more detail above and below. In one of the areas systematically surveyed by Human Rights Watch in April, all villages were partially or totally burned. Food storage containers and other items necessary for the storage and preparation of food were all destroyed.

The situation was the same in another area surveyed – less systematically, because of the presence of Janjaweed in many of the villages burned – between the villages of Misterei and Bayda. The only civilian life encountered was a terrified group of some fifteen people – men and women, all pitifully thin – who were attempting to reach their former village to dig up buried food stores. Many villagers reported having started burying their grain – in pits almost ten feet deep – in recent months in anticipation of attacks on their villages. “We began burying grain about four months ago,” said thirty-five-year-old Omar, of Gokar village. “But there is no way to go back to get it. If they see you, they kill you.”73

In some parts of Darfur, Human Rights Watch received reports that Janjaweed forces deliberately dug up and destroyed buried grain in some villages or beat people they found trying to return and salvage these food stocks.74

Hundreds of villages have been targeted by the government’s campaign of deliberate destruction. On February 7, 2004, Sildi, south-east of Geneina, was attacked, first by air and then by land. Eyewitnesses said thirty villages were attacked, in a matter of days, in the sweep that destroyed, Sildi – Nouri, Nyirinon, Chakoke, Urbe, Jabun, Bule, Dangajuro, Gundo, Jedida, Arara, Kastere, Galala, Nyariya, Werjek, Sildi, Araza, Noro, Roji, Stuarey, Kondi, Ardeba, Cherkoldi, Ustani, Takata, Byoot Teleta, Kikilo, Hogoney, Ambikili, Mishedera. In other incidents documented by Human Rights Watch, up to fifteen villages were attacked and destroyed in a single day as recently as March 2004.

One farmer from Sildi, 40-year-old Ahmad, said “the Janjaweed came with horses and camels and behind them the army with cars. Janjaweed on horses killed the men and took the cows. Janjaweed on camels took the sorghum, clothes and beds. Soldiers in four cars were shooting. They killed 13 people including two women, but more died later from their wounds. Everyone wore uniforms. We saw nothing but uniforms. They said: ‘We aren’t going to leave any of you here. We are going to burn all these villages.’

“The government and the Arabs came together at 8:00 a.m., while people were praying” said twenty-five-year-old Zeinab, a mother of four from Miramta. “They came in cars and on camels and horses. The Janjaweed were wearing government clothes [army uniform]. Without warning, they began to burn the village and shoot civilians. We put the children on donkeys and on our backs. Some we pushed like cars. They left 80 percent of the village burned.”75 Zeinab’s husband, Mohammed, said the killing was indiscriminate. “They killed everything black – guns or no guns, cattle or no cattle. This is the program: they don’t want African tribes in this place.”76

The government and Janjaweed forces have implemented a similar pattern of deliberate destruction in Fur areas of West Darfur. Around Bindisi in Wadi Salih province, forty-seven villages were destroyed between November 2003 and April 2004. Seven of thirteen villages in the Arwalla area and up to forty villages around Mugjir were looted and totally or partially destroyed. Most of the villagers were forced into neighboring larger towns, almost entirely destitute.

Destruction of Mosques and Islamic Religious Articles

In addition to villages and civilian property, the Sudan government has engaged in the systematic destruction of mosques and the desecration of articles of Islam in Darfur. The African Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa of Darfur, unlike the African population of southern Sudan, are Muslims. Almost all Darfurians belong to the Tijaniya sect of Sufi Islam that extends from Senegal to Sudan.

In the past year, government and Janajweed forces have killed imams, destroyed mosques and prayer mats. In some villages, they have torn up and defecated on Qorans.

“We do not know why the government burns our mosques and kills our imams,” said Imam Abdullah, sixty-five, of Jalanga Kudumi. “Our Islam is good. We pray all the time. We read the Qoran all the time.”

Yet government forces and Janjaweed have burned at least sixty-five mosques in Dar Masalit77 and have killed scores of people in mosques. Janjaweed who attacked Urum in November 2003 killed sixteen men as they mourned eighty-year-old Yahya Abdul Karim, and the imam and his orphaned three-year-old grandson. Janjaweed also rode into the mosque in Mulli and shot dead ten people including the imam, Yahya Gabat.

In Sandikoro, a joint army-Janjaweed force tore Qorans and defecated on them. In Kondoli, they killed the imam, Ibrahim Durra, the second imam, and the muezzin during prayers.

“The government wants to kill all African people, Muslim or not Muslim, so as to put Arabs in their places,” said Imam Abdullah. “They are not good Muslims.”78

Killings and assault accompanying looting of property

While most attacks on villages are carried out by a combination of Janjaweed and government forces, it is the Janjaweed whom villagers blame for the lion’s share of the looting that has stripped the Masalit and Fur of much of their wealth – primarily cattle, but also horses, goats and sheep.

The difference between the Janjaweed and government looting of recent years and the looting of “Arab nomads” in the past is that much of the looting today is part and parcel of a deliberate policy of forcible displacement and is usually accompanied by widespread killing. The theft of cows – seen by many Masalit as a “reward” to the Janjaweed for “Arabization” services rendered to the government – now goes hand in hand with the deliberate and widespread killing of those of Masalit and Fur ethnicity.

In the words of Asha, a sixty-two-year-old woman from Kudumule village: “The problem began ten years ago. It began with the stealing of cows. Two years ago they started killing our men.”79

On April 23, 2003, Janjaweed attacked the weekly market in Mulli, east of Geneina on the Habila road, and killed forty-three people – many of them in the mosque.80

“Near to the market there is a place for prayers,” said Ali, a twenty-eight-year-old farmer. He described how the attackers killed the imam and ten people praying, then shouted racially derogatory invectives as they turned on others:

It was 2:30 p.m., time for prayers. The Janjaweed went in, on foot and on horseback, and killed ten people including the imam, Yahya Gabat. Then they turned and started shooting into the market. The bullets were falling like rain and they were shouting: 'Kill the Nuba! Kill the Nuba!' They killed my seventy-five-year-old aunt, Kaniya Hassan, because she refused to let them take her sheep and goats. 81Futr, twenty-seven, had gone to Mulli for market day and witnessed the same attack. “It was 2:30 p.m. and some people were praying; others were in the market,” he said:

The Janjaweed came and surrounded the market. At first people thought they had come to protect it. But then they began to shout: 'Kill the Nuba!' and they attacked. They had RPGS and M79 grenade launchers and killed many people and stole everything from the market 82Musa, twenty-five, was on the eastern side of the market when this attack began. “Most of the Janjaweed were wearing uniforms,” he said. “They stole everything – sugar, money. If you refused to hand something over, you were shot. They killed about thirty people in the market.”83

Ali, thirty, said fifty Janjaweed came from the east with camels and horses. “They had guns and attacked the market. There was no army. Some people were praying in the mosque. They shot indiscriminately at everyone. After that everyone ran away. They stole sugar, meat, everything in the market. They stayed in the market for one hour.” Ali, joined the SLA after the attack.84

No one asked the authorities for redress; they considered the Janjaweed to be the authorities. Futr said about the attackers: “They wore the same uniforms as the army. Nobody complained to the government. We know these people are from the government. They always say: ‘We are the government.'” 85

Six young men were killed in the village of Gozbeddine on October 1, 2003, following the burning of the village the previous day. Idriss, a forty-three-year-old farmer, said the six returned to the village to collect their cows but encountered the Janjaweed. The young men tried to run but were killed as they fled. 86

The Janjaweed brought camels into the village and they ate all the sorghum. They burned the village and stole all my things – including fourteen cows. They were shouting: ‘Kill the Nuba! Kill the Nuba!’ All this is because we are black. We could defend ourselves against the Arab nomads, but not against the Janjaweed. The government has given them very good guns and attacks with them.87

On February 13, 2004, Janjaweed entered the village of Abun to look for cattle. Nearby villages had already been bombed by Antonovs and burned, and Abun was empty but for men who had stayed behind to try to bury food stocks and other non-perishable items in anticipation of being able to return one day. Jamal, a native of Abun, said the Janjaweed killed one man – twenty-four-year-old Adam Bakhit – and captured and beat ten others, asking them: “”Where are the cows and the camels?”88

They beat them very hard. They said: ‘We know the cows and camels are in Chad and must get them.’ They asked for guns. They searched but didn’t find any. They burned all the houses that weren’t visible from the main Geneina-Habila road. They took blankets, money and clothes. They took animals. 89

The Janjaweed were divided over whether to kill the prisoners or not. They finally released them and ordered them away from the village for good: “‘We don’t want to see you again in this place. It is for us, our camels and cows. Leave it soon.'”90

Much of today’s cattle rustling is organised on an almost industrial scale. Dozens of displaced villagers told Human Rights Watch that stolen cows are gathered in Janjaweed cattle camps or “collection points” – the largest of them reportedly at Um Shalaya – from where they are driven to the government slaughterhouse in Nyala for export from Nyala, by air, to Arab countries like Libya, Syria and Jordan.91

“It’s very, very big business – and brings the government a lot of money,” one witness said. “That’s why the government likes the Arabs. They don’t get much return from poor farmers.”92

Killings during looting expeditions are not limited to men, and include women and children. Kudumule, outside Misterei, was attacked, on February 24, 2004.

“The Janjaweed came and attacked the village and stole the cattle,” said sixty-two -year-old Asha. “Abakar Mohammed was defending the village. He was thirty years old. When he went to get the cattle, they killed him. They also killed his seven-year-old niece, Mariam Ahmad.”93

Villagers seldom protest Janjaweed actions to army or police, believing the army to be one with the Janjaweed and the police to be ineffectual and powerless. On the rare occasions that they have protested, they have not had satisfaction.

Also on February 24, 2004, Janjaweed from outside Misterei looted large numbers of cows from inside the town. Most of these cows belonged to displaced people who had gone to Misterei for safety from the joint government-Janjaweed attacks on villages. The people appealed for help to the local army chief – a Dinka from southern Sudan, known to the Masalit residents only as Ango.

“Ango went and brought about half of the goats and sheep that had been taken, but no cows,” said twenty-five-year-old Mohieddine. At this point, some people left for Chad. Many others followed after the next large-scale looting a month later.

On March 22, the Janjaweed made a second raid and stole 400 cows. They wore the same uniform as the government. Ango followed again and again brought half of the goats and sheep but no cows. We decided to go to Chad and left in the night.94

It is not just the theft of assets like livestock that send Masalit fleeing to Chad. For poor people who have few assets, small losses hit hard. Omar, a thirty-seven-year-old farmer from Gokar Aminta, left for Chad after Janjaweed stole his watch in the street. The Janjaweed abused and persecuted those whom they did not expel:

They came into Gokar with a group of thirty soldiers and moved with them into the police station. They called a meeting in the police station and said: 'Your village will not be burned. You must stay here.' But then they began to torment us. They came into the houses and took whatever they wanted. They hit people. What did the soldiers do? Nothing.95Hawa, thirty-five, was one of those robbed and beaten in her home, then accused of being the wife and mother of SLA rebels to put her in her place.

The Janjaweed came to my house at midday and took clothes and radio and blankets and watch. They asked: ‘Where is your husband?’ I said he went to bring water. They hit me with sticks and said: ‘Your husband is SLA. Your son, too.’96

Displaced Masalit, Fur and Zaghawa civilians and residents in the larger government-controlled towns continue to be assaulted and sometimes tortured by Janjaweed for loot or suspected rebel affiliation even once they have fled their villages in the rural areas.

In March 2004 in one of the larger towns in Wadi Salih, Janjaweed detained a wealthy Fur community leader, his wife and daughter, beat them all and hung the man upside down with ropes around his neck and arms in an effort to obtain money and goods from the family.97

In a case of torture reported from the Garsila area in April, a Fur man was detained and whipped until all the skin was flayed from his back. The whip handle was then used to gouge holes in his flesh. Human Rights Watch also received reports of men being buried alive around Garsila and Deleig by janjaweed members.98

Displaced people continued to report that Janjaweed committed crimes against them including violent attacks, disappearances, and looting of their remaining livestock. These crimes have been committed in numerous displaced camps around Geneina, Nyala, and other large towns under government control.99 Even relief supplies distributed to them have been looted.

Rape and other forms of sexual violence

Rape appears to be a feature of most attacks in Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa areas of Darfur. The extent of the rape is difficult to determine since women are reluctant to talk about it and men, although willing to report it, speak only in generalities. Human Rights Watch received reports of rape in roughly half the villages it confirmed were burned. The real figure is certainly higher.

In the villages of Dingo and Koroma in Dar Masalit, for example, men said the Janjaweed “took girls into the grass and raped them there.” One of the girls raped was only thirteen years old. Near Sissi, three women, aged thiry-two, twenty-two and twenty-five, were abducted at a water hole and taken to Nouri school, which was abandoned, and were raped. 100 In the village of Dureysa, on the Masalit-Fur border, a seventeen-year-old girl who resisted rape was killed and her naked body left on the street.

Rape continues to take place in and around the displaced settlements and towns under government control, even after civilians have fled their villages. In April, a displaced Fur woman collecting firewood outside Garsila town was attacked by Janjaweed who tried to rape her. She was beaten so badly she later died.101

Efforts to Prevent Return of Displaced Masalit and Fur

Janjaweed are now camped in some of the villages they have burned in Dar Masalit, guaranteeing that no Masalit civilians will return to the area. An SLA commander, Abdul Qassim “Toba”, told Human Rights Watch that a string of villages on the eastern side of Dar Masalit were occupied by Janjaweed in recent months – among them Tullus, Urum and Dureysah. From here, he said, “they are going into the mountains every day looking for the SLA.”

Human Rights Watch also saw Janjaweed camped in villages far from the SLA’s bases in the mountains – close to the border with Chad on the western edge of the Masalit area. From these villages, the Janjaweed mounted raids across the border into Chad and exerted some control over the movement of displaced persons. Their mere presence close to the border ensured that refugees in Chad did not attempt to cross back into Darfur to salvage buried grain or other belongings.

On March 25, Aisha, a 35-year-old woman from Abun, left Chad in the night to attempt to bring food from her village. She and one other woman walked for two days. “We found the Janjaweed in our houses, sleeping on our beds,” she said. “Only Janjaweed, with cows. They wore uniforms like the army. If they saw me, they would have killed me.”102

Some Fur villages around Wadi Salih remain intact, but only because residents have paid large sums of “protection” money to Janjaweed who control their movements and circulation in the area. Witnesses told Human Rights Watch that even severely ill or wounded villagers were forced to remain in their home villages and denied access to larger towns with hospitals and health care unless they had janjaweed escorts. Displaced in government and Janjaweed-controlled towns continue to suffer systematic attacks. Even old women trying to collect firewood outside the towns risk beatings and rape if they leave the towns.

The insecurity coupled with the complete destruction of food stocks and other essentials such as water sources further guarantees that displaced Masalit will not return to their home villages. The repeated attacks by Janjaweed and government forces, burning of villages and destruction of livelihoods has left displaced Masalit and Fur destitute and dependent on relief aid.

A recent UN humanitarian mission to Darfur found that people want to return home but are unwilling to do so until they are reassured that security has been restored.103 Some have attempted to return, but often they end up fleeing again as a result of renewed attacks. In some Fur areas of West Darfur, civilians have paid sums of money to the Janjaweed in order to return to their villages, only to face further attacks once they returned. These examples clearly indicate the impossibility of return while the janjaweed remain encamped in and around the villages of the displaced.

Recent U.N. reports indicate that in some places the government is now trying to force people to return to their villages despite their lack of action to disarm and disband the Janjaweed, or remove them from the areas they occupy.104 These efforts are very likely due to increased international pressure and awareness of the massive humanitarian crisis threatening the region, but no returns should take place until adequate security is in place including dismantling and removal of the Janjaweed forces.

Occupation and Resettlement of Masalit Villages by Janjaweed

Masalit persons in Geneina reported seeing women and children they said were the families of Janjaweed fighters moving south through Geneina, beginning at the end of March 2004. The movement coincided with a broadcast on state-run Geneina radio calling one of the most feared Janjaweed leaders, Hamid Dawai, “the emir of the emirate of Dar Masalit”. One Masalit chief reported that these woman and children were travelling with an army escort.

A twenty-seven-year-old farmer called Feisal said he saw “Janjaweed families coming from the north with their tents and baggage” in the first week of April. “They arrived in Geneina in cars with government cars behind,” he said. “From Geneina, they took cars south to Habila and Forbranga. Big cars, with thirty to forty in each car. I counted about thirteen families. Dar Masalit is becoming an Arab area. They are going to bring their families.” Asked how he recognized the travellers as Arabs, he said: “Why do you ask this? Do you think we do not know? It is their color, their language and their clothes. They are not as we are.”105

Although the movement of families appears to be small at this time, a number of displaced men have reported seeing Arab women and children in places where previously there were only armed men. Hassan, a twenty-two-year-old farmer from Gokar, reported seeing “Arabs with their wives and children and many cows” in the villages of Tur, Urum and Tullus.106

An elderly man from Tunfuka said he found a handful of Arab families in Tunfuka when he went back one night recently to try to salvage belongings. He said one family had built a new dwelling, not in the traditional Masalit style, while another was living in an unburned hut that had belonged to a man called Abdul Magid Fadhel. The Arabs had built a new mosque in the village, he said. Asked what the women were doing, he said: “They were gathering all the food and giving it to the government, who came to collect it in trucks.”107

Impeding the free movement of civilians

In recent months, with greater international attention on the atrocities in Darfur, there have been increasing reports of the Janjaweed and government forces obstructing displaced civilians from seeking refuge into Chad or moving to large urban centers like Nyala. Masalit and Fur leaders believe this is to prevent information about the ethnic cleansing of Darfur reaching the outside world. Suspicions that these efforts are encouraged by the government are strengthened by the official letter to the only Masalit omda whose villages have not been burned, apparently because of their proximity to Chad, urging him to “come back to Sudan with all your people.”108

One day before this local leader received the letter, sent by local government officials, Janjaweed leader Hamid Dawai called a meeting with Masalit leaders brought to Misterei in army trucks and asked them to organise “security” to stop their people crossing into Chad. He promised large payments if they did. Two people who attended the meeting said the Masalit told Dawai: “We don’t like your money. We don’t believe in your security. We are suffering from Arab militias.” Damai responded: “If you don’t make security, I will kill all your civilians.”109

A month earlier, Janjaweed who had moved into the army base in Misterei closed the road to Chad after people began leaving in despair at widespread looting.

“The Janjaweed said: ‘Why are you going? We are here to save you’ – and closed the road,” said twenty-five-year-old Mojieddine. “The Janjaweed are at the heart of the whole administration.”

By March 2004 there were ten Janjaweed checkpoints between Adre (just inside the Chad border) and Geneina. Refugees described the circuitous routes they had to take to avoid the checkpoints, increasing by several days their journeys to safety in Chad.

In addition to trying to prevent people from leaving Darfur and crossing into Chad, government forces have urged Chadian authorities to pressure the Sudanese refugees to return to Darfur, despite the volatility of the situation, the fact that security remains absent in the towns and rural areas of Darfur, and government forces and Janjaweed continue to enjoy full impunity for their attacks on civilians.

On April 14, 2004 a Sudanese government delegation accompanied by Chadian officials and military convened a meeting with Sudanese refugee leaders in Forchana refugee camp in Chad, home to thousands of Masalit and other Sudanese refugees. Most refugee leaders refused to participate. A few individuals eventually turned up and the Sudanese delegation demanded that the refugees return to Darfur.

The meeting deteriorated as the refugees began throwing stones at the Sudanese delegation and the Chadian military fired shots in the air. Two refugees were apparently arrested and detained and several were allegedly beaten by Chadian soldiers. 110 The Sudanese government issued a statement that refugees were returning to Sudan shortly thereafter, despite fresh evidence that civilians continue to flee Darfur into Chad.111

Janjaweed manning checkpoints detain, rape and kill Masalit and Fur civilians and tax vehicles moving along roads, discouraging many from attempting to travel between towns – or from towns to the bush. They impose “taxation” on cars moving between towns, and threaten death or imprisonment if payment is not met. They threaten the drivers with accusations: “You always carry rebels from the bush to the towns”.

Feisal from Nouri was stopped at a Janjaweed checkpoint at Mechmairey, on the road to Geneina, early in 2004. The Janjaweed, who had a Thuraya telephone, demanded that he and his fellow travellers pay £200,000 Sudanese or “we will kill seven people”. In the end they settled for £50,000 and the car continued on to Geneina. At the first Janjaweed checkpoint outside Geneina they were stopped again and a Janjaweed with a Thoraya telephone asked: “Why didn’t you pay the full amount in Mechmairey?”112

Displaced Fur civilians in Garsila, Deleig, Mugjir and other towns controlled by government forces and Janjaweed are regularly forced to pay bribes and subjected to violence by Janjaweed “officials” when attempting to move outside the displaced settlements and camps around these towns. Women who attempt to leave the towns to collect firewood run a serious risk of assault and rape.

Civilians are also prevented from travelling from smaller villages to these larger towns without government authorization. The larger towns are currently the only places with any functioning social services including health care. One witness from a village approximately 15 km from Garsila told Human Rights Watch that his child died after he was forced to wait six days for a Janjaweed escort before taking the child to a health center in Garsila.113

Due to the restrictions on movement and continuing attacks by Janjaweed militias, many displaced civilians lack essential items such as shelter materials, adequate water, food and fuel for cooking. Even where food is available in local markets, displaced Fur and Masalit civilians are often unable to travel to those markets to purchase it.

“ETHNIC CLEANSING” IN WEST DARFUR

In this report, Human Rights Watch has documented a pattern of human rights violations in West Darfur that amount to a government policy of “ethnic cleansing” of certain ethnic groups, namely the Fur and the Masalit, from their areas of residence.114 Other credible sources, in particular the Emergency Relief Co-ordinator of the U.N. system and the former Resident Co-ordinator of the U.N. system in Sudan, Mukesh Kapila, have made similar claims.115

Although “ethnic cleansing” is not formally defined under international law, a U.N. Commission of Experts has defined the term as a “purposeful policy designed by one ethnic or religious group to remove by violent and terror-inspiring means the civilian population of another ethnic or religious group from certain geographic areas…. This purpose appears to be the occupation of territory to the exclusion of the purged group or groups.”116

The Commission of Experts elucidated the meaning of “ethnic cleansing” as it occurred in the former Yugoslavia:

The coercive means used to remove the civilian population from the above-mentioned strategic areas include: mass murder, torture, rape and other forms of sexual assault; severe physical injury to civilians; mistreatment of civilian prisoners and prisoners of war; use of civilians as human shields; destruction of personal, public and cultural property; looting, theft and robbery of personal property; forced expropriation of real property; forceful displacement of civilian population.... 117The United Nations has repeatedly characterized the practice of ethnic cleansing as a violation of international humanitarian law, and has demanded that perpetrators of ethnic cleansing be brought to justice.118 The individual human rights abuses that characterize ethnic cleansing are crimes against humanity and war crimes.

Human Rights Watch has found credible evidence that the government of Sudan has purposefully sought to remove by violent means the Masalit and Fur populations from large parts of Darfur in operations that amount to ethnic cleansing. The attacks directed against civilians, the burning of their villages, the mass killings of persons under their control, the forced displacement of populations, the destruction of their food stocks, livelihoods and the looting of their livestock by government and militia forces are not merely a scorched earth tactic or an element of a counterinsurgency strategy. Their aim appears to be to remove those ethnic groups from large areas of the region and redistribute this population, mainly into the vicinity of government-controlled towns where they can be concentrated, confined and controlled.

The subsequent denial of humanitarian assistance to this population by the government of Sudan, in conditions where the population has been rendered entirely dependent on relief, can also be considered as part of a strategy to weaken and perhaps destroy a large proportion of the displaced population and prevent their return to their home villages. The situation has been exacerbated by the occupation and apparent resettlement of some Masalit and Fur areas by Janjaweed and related Arab ethnic groups. The ethnic make-up of the region will be permanently altered if the large-scale displacement that has occurred is not urgently addressed and reversed.