Abstract: The Yemen-based Houthis’ top priority is the continued development of their unmanned vehicle and missile programs. Both programs are vital to the Houthis’ ability to exert leverage over both their domestic and external enemies. Securing supply chains and funding for the programs, especially funding and supplies that are independent of Iran, is a key objective for the Houthi leadership. To this end, the Houthis have deepened their relationship with Yemen-based al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). AQAP, in turn, has opened new doors for the Houthis to interact with Horn of Africa-based militant groups such as al-Shabaab. Both AQAP and al-Shabaab now act as facilitators and, to a degree, as partners that help the Houthis smuggle needed materiel into and out of Yemen. These relationships are also vital to the Houthis’ expanding efforts to fund their weapons programs and the broader organization. The Houthis’ relationship with al-Shabaab and Horn of Africa-based smugglers points to the organization’s growing footprint in the Horn of Africa.

The last 14 months have demonstrated that the Houthis’ prioritization of their missile and UAV programs is vital to the Yemen-based group’s ongoing transformation to a near-state power.1 The once small band of guerrilla fighters who were confined to a few hundred square miles of rugged terrain in the northwest corner of Yemen have, over the course of 20 years, evolved into an organization that now has regional reach and the ability to impact the global economy. Since declaring their support for Hamas following Hamas’ October 7, 2023, attack on Israel, the Houthis have targeted at least 134 vessels with missiles, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).2 The Houthis have also launched missiles and UAVs at Israel, with at least one successful strike on an apartment block in Tel Aviv that killed one Israeli.3

The economic ramifications of the Houthis’ attacks are reverberating through regional economies. The number of vessels transiting the Suez Canal has fallen by more than 50 percent since October 2023 as shipping companies are forced to route ships around the Cape of Good Hope.4 Egypt, a country that is struggling with a weak economy, has seen critical hard currency revenues from the canal decline by six billion USD.5 a Companies and consumers, especially in Europe, face higher prices due to increased shipping costs.6 Dockings at the Israeli port of Eilat are down by 85 percent and contributed to the port operator declaring bankruptcy in July.7 The threat of attack by the Houthis has become so severe, despite costly U.S., U.K., and E.U. efforts, that some warships avoid transiting the Red Sea. In October 2024, a German Navy frigate was forced to sail around the Cape because it was not adequately equipped to defend itself against possible attack by the Houthis.8 In desperation, some shipping companies are now paying the Houthis not to attack their vessels.9

The Red Sea and Gulf of Aden campaign has been a resounding success for the Houthis with few costs.b The attacks have set the Houthis up as one of the premier members of the “Axis of Resistance,” and messaging that paints the Houthis as “defenders of the Palestinian people” has helped bolster domestic, regional, and even international support.10 c

These political and financial gains would not be possible without the group’s Iranian-supported UAV, UUV, and missile programs. These weapons systems provide the Houthis with tactical and strategic reach that they leverage both in and outside Yemen. It was the Houthis’ use of UAVs and missiles to target Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that forced both countries to reevaluate how to approach the war in Yemen.11

For the Houthi leadership, there is no higher priority than the advancement and continuity of these two programs.12 Maintaining the inflow of the materiel needed to assemble and produce UAVs, UUVs, and missiles is a critical mission for the Houthis. A growing percentage of the required materiel for these programs transit the Horn of Africa via a web of intermediaries.13 Consequently, the Houthis are prioritizing the build-out of their presence in the Horn of Africa to help secure supply chains. To further facilitate the movement of illicit and licit goods, the Houthis are also building durable ties with armed groups, namely al-Shabaab, and smugglers that operate in Somalia and Puntland.14 The Houthi leadership views enhanced influence in the Horn of Africa as both critical to maintaining the flow of needed materiel and to securing new revenue streams and increased political leverage.15 For the Houthis, one of the first steps toward enhancing their covert presence in the Horn of Africa was the formation of a pragmatic alliance with Yemen-based al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

This article begins by examining how AQAP’s shifting priorities have driven them and the Houthis into a relationship based on some shared objectives and mutual benefits. The Houthi-AQAP relationship is looked at in some detail as cooperation between the two former enemies has helped the Houthis establish ties with Somalia-based al-Shabaab and Horn of Africa-based illicit networks. This nexus of shared interests between the Houthis, AQAP, al-Shabaab, smugglers, and Iran is looked at in light of the Houthis’ need to generate revenue to sustain their organization and secure independent supply chains for their weapons programs. The article concludes by assessing how the Houthis’ expanding ties to Horn of Africa-based groups align with and reinforce the Houthis’ longer-term aims to enhance their existing leverage over domestic and external enemies by further developing and securing their weapons programs and revenue streams. Research for the article was carried out during multiple trips to the region during 2024. The article draws heavily on interviews with a range of Yemen and region-based officials, practitioners, and analysts.

New Friends and Illicit Networks

The Houthis were once one of AQAP’s most formidable enemies. AQAP’s membership, which nominally adheres to militant salafi ideologies, regarded the predominately Zaidi Shi`a Houthis as heretics. Now, the two organizations are increasingly cooperating due to shared enemies and business interests.

The Houthis and AQAP fought pitched battles from 2014 to 2016 for control of parts of the governorate of al-Bayda in central Yemen and in parts of Marib, Taiz, Lahij, and Aden where AQAP fighters were integrated into many anti-Houthi militias.16 Following its 2016 retreat from the Yemeni port city of Mukalla, which it had controlled for a year, AQAP began adopting more pragmatic approaches to surviving Yemen’s complex and interlocking wars. These approaches included acting as “guns for hire” for multiple armed groups as well as for Yemen-based smugglers.17 AQAP’s fighters and operatives were valuable commodities for anti-Houthi militias. Many of these men were relatively well trained, and, most significantly, more senior operatives and fighters maintained familial and business links to important tribes in critical areas such as al-Bayda, Abyan, Shabwa, and Hadramawt.18

In addition to acting as mercenaries, AQAP’s diffuse leadership also worked to enhance the organization’s role in Yemen’s thriving illicit networks.19 Hiring fighters out as mercenaries provided AQAP with some revenue, but it was the organization’s enmeshment, or more accurately re-enmeshment, with smuggling networks that provided an influx of cash for the group’s elites. During AQAP’s 2011-2012 occupation of parts of Abyan, AQAP operatives helped facilitate the trafficking of drugs, humans, and weapons from Yemen’s southern coasts into the interior.20 It was AQAP’s relationship with al-Shabaab, whose fighters fought alongside AQAP in Abyan, that helped AQAP deepen its ties to Horn of Africa-based smugglers and some of their Yemeni counterparts. While AQAP was forced out of most of Abyan and Shabwa in 2012, the group’s connections with Yemen and Somalia-based smugglers as well as al-Shabaab persisted.21

The core of the AQAP-al-Shabaab relationship is built around shared business interests. As with most terrorist groups, AQAP and al-Shaabab are, first and foremost, businesses dedicated to making money to sustain their organizations and enrich elite members of the groups.22 While some of AQAP’s senior leadership has been successfully targeted over the last 10 years, the organization’s cellular structure—which mirrors al-Shabaab’s—means that the loss of senior leaders does not sustainably impair its broader workings, which focus more and more on profit-making activities.23

Since 2020, AQAP has markedly scaled up its involvement in smuggling activities. The group offers a menu of services for smugglers and the grey-zone businesses that abound in Yemen.24 These services include defending and escorting high-value shipments, the facilitation and delivery of illicit goods from Somalia-based intermediaries, intelligence gathering, contract killing, and even the management of tribal relations.25 The smuggling of illicit goods, from high-end weapons systems and captagon to humans, brings enemies together in Yemen.26 Members of warring tribes, political rivals, parties to blood feuds, and salafis and Zaidis frequently work together to ensure that illicit goods arrive at their final destinations. Those destinations include all parts of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, and other countries. In many parts of Yemen, especially in parts of southern and eastern Yemen, smuggling is the lifeblood of local economies. AQAP’s involvement in the smooth operation of smuggling routes is one of the reasons the group now cooperates with the Houthis.27 However, the two organizations also have a shared enemy in Yemen’s Southern Transitional Council (STC).28

AQAP and the Houthis are both battling forces allied with the STC. Since 2021, AQAP has focused much of its efforts on targeting UAE-supported forces allied with and commanded by the STC. The animus between AQAP and the STC and allied forces is partly rooted in the 2021-2022 battles between Islah-allied forces and the STC for control of the governorates of Shabwa and Abyan.29 Shabwa is home to much of Yemen’s remaining oil wealth, and both governorates are transected by vital smuggling routes. Despite officials allied with Islah and the STC both being members of the Presidential Leadership Council (PLC), Islah-allied forces and the STC fought periodic but fierce battles for control of Abyan and Shabwa from 2021-2022.30 At the same time, STC-aligned forces, namely the UAE-backed Giants Brigades, also fought the Houthis in Shabwa. The Houthis were attempting to retake parts of Shabwa from the STC and Islah. The STC defeated Islah, thwarted Houthis advances in Shabwa, and took control of most of Abyan and Shabwa by mid-2022.31

While all sides in the conflict in Yemen routinely accuse one another of working with AQAP, AQAP’s leadership expressed anger over the STC takeover of Shabwa and its expulsion of the Islah-aligned governor in December 2021.32 AQAP operatives and fighters have long been active in Marib, where Islah-aligned tribes and militias predominate.33 This is not to argue that Islah is allied with AQAP, but there are overlapping interests. AQAP has deep roots in Abyan and Shabwa and abiding ties to tribes and sections of tribes in both governorates.34 Most significantly, AQAP wants to maintain access to the smuggling routes that lead up from the two governorates’ extensive coastlines to the Yemeni interior, which includes Houthi-controlled governorates. For the Houthis, these smuggling routes are vital as is the eventual control, if they are successful, of Shabwa’s oil and gas resources.

Since early 2023, the pragmatic alliance between AQAP and the Houthis has deepened further. The Houthis and AQAP have engaged in multiple prisoner exchanges and increasingly share intelligence on common enemies, namely the STC.35 There are also indications that the Houthis are providing AQAP with weapons, including UAVs which are in high demand by AQAP and al-Shabaab.36 Like most states and non-state actors, AQAP is a keen observer of how UAVs, especially First Person View (FPV) UAVs, are reshaping battlefield dynamics in the war between Ukraine and Russia. While, due to their distrust of AQAP, it is unlikely that the Houthis would provide AQAP with UAVs with significant range, the Houthis are providing AQAP with lower-end UAVs.37

The alignment of the Houthis’ and AQAP’s near-term interests have helped open the door for the Houthis to cooperate with Horn of Africa-based groups like al-Shabaab. The Houthis’ cooperation with Somalia-based al-Shabaab is an outgrowth of the Houthis’ working alliance with AQAP. The three organizations, as well as Yemen- and Horn of Africa-based smugglers and Iran, have formed a kind of symbiotic relationship whereby all parties benefit from increased revenue, access to illicit goods, and greater political leverage.

A Nexus of Shared Interests

The Houthis, Iran, AQAP, and al-Shabaab all benefit from a developing nexus of shared interests.38 The cornerstone of these symbiotic relationships is the exchange of weapons. Al-Shabaab has long struggled with acquiring higher-end weapons. While Somalia and semi-autonomous Puntland are hotspots for arms smuggling, most of the weapons flow out to other countries in Africa or the region.39 Consequently, the prices for small and medium arms in Somalia are higher than in Yemen, which was awash in weapons even before the start of the civil war in 2014. Yemeni arms smugglers have long exploited the arbitrage that exists between Yemeni and Somali arms markets. The Yemen-Somalia arms trade is highly lucrative.40 For example, a crate of Chinese or Iranian-made AK-47s can be sold in Somalia for up to five times what they cost to acquire in Yemen. Margins for other weapons and materiel such as sniper rifles, RPG-7s, man-portable mortars, and night vision devices are considerably better. Modifiable commercial and military-grade UAVs command even higher premiums.41

The Houthis and elites loyal to the Houthis have been involved in the arms trade since at least 2010. After their September 2014 takeover of Sana’a, Houthi involvement in the arms trade increased due to both their greater political power and reach and due to their access to much of the Yemeni Armed Forces’ armaments and stockpiles.42 The Houthis’ involvement in the weapons trade is a significant source of revenue for the group and provides them with domestic political leverage. Somewhat ironically, the Houthis give weapons to some recalcitrant tribes to secure support. They also reward dedicated commanders and units by providing them with superior small arms that are often regarded as the personal property of the officers and soldiers.43 As in many countries, weapons are a kind of hard currency in Yemen that cement relationships and grease political and financial transactions.

The weapons trade between Yemen and Somalia is fundamental to the Houthis’ initiative to enhance their relations with al-Shabaab and other Horn of Africa-based armed groups and illicit networks. Yemen-based arms smugglers have been shipping weapons to Somalia since the fall of Siad Barre in 1991.44 There is nothing new about weapons flowing from Yemen to Somalia; Yemen has long been a regional arms bazaar. However, since 2023, the Houthis have asserted more control over the trade, which is, at least in part, managed by their intelligence wing.45 While there are weapons flows from non-Houthi controlled parts of Yemen to Somalia and elsewhere, the Houthis—in cooperation with chosen smugglers, AQAP, and al-Shabaab—are now the major actor in the trade.46 Just as in Yemen, the Houthis are using weapons, and especially promises of access to UAVs and military expertise, as a way of acquiring support from groups in Somalia. The Houthis, in cooperation with Iran, are also using the provision of weapons as a way of securing supply chains for their drone and missile programs.47

Since at least 2019, the Houthis have been assembling and manufacturing many of the UAVs they use and some of the less sophisticated missiles.48 Many of the inputs for these programs are dual-use items. Others, such as guidance and optical systems, gyroscopes, engines, and chemicals for rocket fuel and explosives, are not and are therefore subject to sanctions. While dual-use items often arrive in the Houthi-controlled port of Hodeida or ports controlled by the Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) and its allies, restricted items are usually smuggled.49 Many of these items are shipped from Iran and other countries on small and medium-sized boats that anchor either off Yemen’s southern coast (coastlines in the governorates of Abyan and Shabwa) or off the coast of Somalia. There, the materiel is offloaded to smaller vessels for transport to Yemen.50 Some materiel is also landed in Somalia both at ports and along the coast where it is broken into smaller shipments that travel on hard-to-detect small boats and skiffs to the Yemeni coast or Yemeni islands in the Red Sea where it is cached for later retrieval by the Houthis or smugglers.51 Like AQAP in Yemen, al-Shabaab as well as some newly revived pirate gangs oversee transshipment and provide security and logistics support for smugglers. There are indications that al-Shabaab wholly controls some of the transshipment operations.52

Much of the materiel transshipped from Somalia is brought ashore in the Yemeni governorate of Lahij, which is under the control of forces nominally allied with the STC.53 Smuggling is a significant source of income for the tribal militias that control most of Lahij where AQAP is also active. The routes begin along Lahij’s coast near Ras al-Arah and pass through al-Subhaia up into the governorate’s northern mountains, which abut the governorates of Taiz, Ad Dali’, and al-Bayda. Smugglers operating in Lahij are also involved in the trafficking of drugs and humans.54

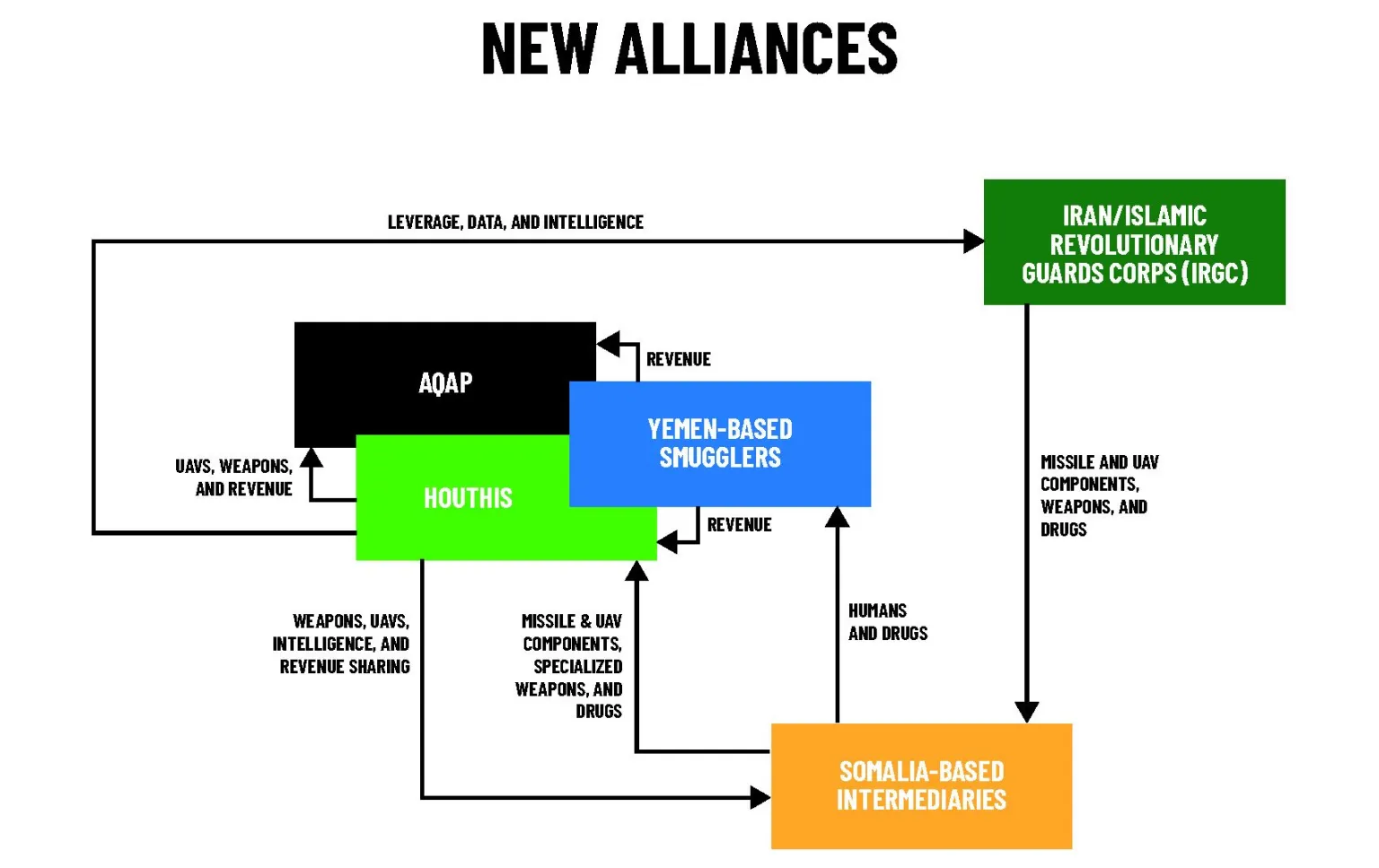

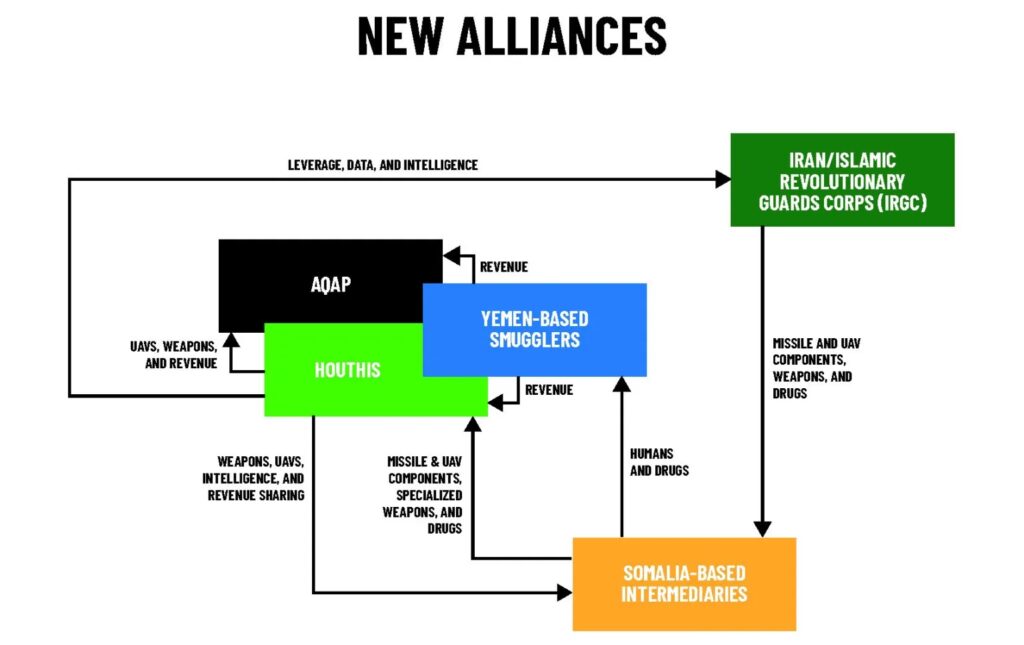

The Houthis, AQAP, al-Shabaab, Iran, and smugglers have developed a relationship from which all benefit. (See Figure 1.) Iran continues to provide the Houthis with needed components for their vital UAV and missile programs, in addition to some small arms.55 In exchange, Iran gets the leverage that comes with a well-armed and capable proxy that shares a long border with Saudi Arabia and occupies land near the strategic chokepoint of the Bab al-Mandeb.56 Iran and Hezbollah, both of which have advisers in Houthi-controlled Yemen, also benefit from being able to collect data from the Houthis’ use of what are primarily Iranian-designed UAVs and missiles against multiple targets, including U.S. and allied warships.57 Al-Shabaab benefits from acquiring small arms, UAVs, and, potentially, war-fighting expertise from the Houthis. All these parties benefit financially. Al-Shabaab has long been involved in human trafficking, which generates tens of millions of dollars for the networks that facilitate the movement of men, women, and children from multiple Horn of Africa nations to Yemen.58 The Houthis and AQAP receive fees from Yemen-based smugglers who move the refugees from southern Yemen toward the Saudi and Omani borders.59

Al-Shabaab, AQAP, Iran, and the Houthis are also involved in drug trafficking, which is almost as lucrative as weapons trafficking. Iran manufactures amphetamines such as captagon and also acts as a conduit for heroin sourced from Afghanistan.60 The Houthis also manufacture smaller amounts of captagon that are used domestically and smuggled into Saudi Arabia.61 However, given the amounts of money that can be generated from the sale of drugs and the ease with which they can be smuggled, the Houthis will almost certainly increase their manufacturing capacity. The drugs, especially captagon, are in high demand in Somalia as well as further afield.62

Yemen’s National Resistance Forces (NRF), led by Major General Tariq Saleh, also a vice president on the PLC, controls much of Yemen’s southern Red Sea coastline. The NRF’s strategic location means that its forces are well-placed to collect intelligence on the movement of Houthi-linked boats and interdict suspicious vessels. Speaking to the author, a senior aide to Major General Saleh warned that the NRF “is seeing increased coordination between al-Shabaab and the Houthis.” The aide indicated that “al-Shabaab operatives ensure that shipments of drone and missile components are safely offloaded in Somalia or its waters and then loaded onto smaller boats that take the contraband to Yemen. In exchange, al-Shabaab receives money, small arms, and guidance from the Houthis.” The aide added that in October, the NRF intercepted a shipment of weapons bound for Somalia from Yemen as well as a shipment of Iranian-sourced radars, missile components, and communication equipment that was shipped from Somalia to Djibouti and then to Yemen. The same aide also told the author that the “NRF has intelligence that indicates that the Houthis intend to supply al-Shabaab with more advanced weaponry that might enable them to target shipping in the Gulf of Aden.”63

Leveraging Chaos

The emerging relationship between the Houthis and al-Shabaab can potentially expand the capabilities of both organizations. Just as access to UAVs and missiles transformed the Houthis from a group whose reach did not extend beyond Yemen to one that can now bomb Tel Aviv, similar access to UAVs could further empower al-Shabaab and other Horn-based militant groups. This could benefit the Houthis by helping al-Shabaab secure more territory and better support lucrative smuggling networks. The Houthi leadership is determined to ensure the durability of the supply chains that allow them to continue to assemble and manufacture the missiles and UAVs, which enables them to keep domestic enemies at bay while also cowing regional rivals. Dependence on Iran for components for the UAV and missile programs, as well as the Houthis’ reliance in part on Iranian money, are both regarded as vulnerabilities by the Houthi leadership.64

Enhancing its relationships with groups such as al-Shabaab and establishing a covert and overt presence in the Horn of Africa helps the Houthis address both vulnerabilities. While Iran remains the source for many of the components required by the Houthis to assemble and, in some cases, manufacture UAVs, UUVs, and missiles, the group is trying to source components, especially multi-use items, from non-Iranian suppliers and companies with no connection to Iran.65 The Houthis possess a well-developed system for procuring needed materials (see Figure 2) and ensuring they arrive in Yemen.66 d This system is adaptive and resilient like most Houthi-run entities. The Houthis’ equally well-developed intelligence wing, specifically the economic intelligence unit, is charged with finding new suppliers for licit and illicit goods. The Houthis are mirroring Lebanon-based Hezbollah’s approach to establishing operatives and connections in Africa and further afield.e

From the mid-1990s onward, Hezbollah worked to establish front companies and covert ties to legitimate companies based in Africa and South America.67 These companies, both knowingly and, in some cases, unknowingly, helped supply and finance Hezbollah. Hezbollah, like the Houthis, feared overreliance on Iran and wanted independent sources of revenue. In the case of Hezbollah, the group drew heavily on expatriate Lebanese communities in West and East Africa and Latin America.68 Many of these communities have deep ties to—and knowledge of—the countries where they work and live. While a minority of Lebanese expatriates may have supported Hezbollah, Hezbollah used mafia-style tactics to threaten others into working with them, often to transport contraband.69 Long-established Yemeni communities exist in almost all Horn of Africa countries, and many operate businesses with regional footprints. The Houthis are targeting some members of these communities to help them continue to acquire licit and illicit goods and materiel.70

The Houthis are equally creative when it comes to financing their operations. The Houthis rely on numerous revenue streams ranging from “taxes” and fees on Yemenis, Yemeni businesses, and imports, to land and property seizure and sales.71 Funds from fees and revenue sharing from illicit networks make up an increasing percentage of the Houthis’ revenue. Like AQAP, the Houthis charge fees for the safe passage of goods and materiel and humans through the territories they control. Fees from shipping companies paying the Houthis not to attack their ships are a new and growing source of income.72 The Houthis also profit from the sale of weapons and military expertise.73 The Houthi leadership is watching closely how Iran and Turkey, in particular, profit from the sale of UAVs and other weapons systems. The Houthis are also undoubtedly taking note of the political leverage that comes from supplying these weapons to various regimes. While the Houthis are years away from developing the capacity to manufacture weapons systems at scale, they do have the ability to assemble, manufacture, and export limited numbers of armed and surveillance UAVs.f The Houthi leadership view the export of weapons and military expertise as areas ripe for expansion.74 Ongoing wars and insurgencies in Sudan, Ethiopia, and Somalia and the overall febrile nature of politics in the Horn of Africa will provide the Houthis with ample opportunities for expanding their reach.

Outlook

The diffusion of drone and missile technology to state, non-state, and near-state actors such as the Houthis is transforming war fighting as well as regional political dynamics. The Houthis’ rapid adoption and incorporation of UAVs and missile technology give them an edge over not only their domestic enemies but also leverage over their regional rivals. These weapons systems combined with the Houthis’ well-developed intelligence capabilities and a martial culture that is rooted in guerrilla warfare, make them an especially formidable foe. The Houthis increasing interest in and cooperation with Horn of Africa-based armed groups and illicit networks, add yet another layer of complexity and risk to an already unstable region beset with brittle states.

The integration of armed non-state groups such as AQAP and al-Shabaab into illicit networks is a well-established global trend. The Houthis’ emerging relationships with both armed groups and with those who run the smuggling networks that link Iran, Yemen, and many of the Horn of Africa nations will, if allowed to persist, provide the Houthis with the more durable and diversified supply chains that they seek. These relationships are undoubtedly already providing the Houthis with new sources of revenue as well as opportunities to exert even greater leverage over both domestic and regional foes. The symbiotic relationship between the Houthis, AQAP, al-Shabaab, Iran, and smuggling networks ensures that all sides have, for now, an interest in ensuring that the relationships continue to evolve. All of these organizations feed off of the instability that they help create. This is especially the case for the Houthis who seem to fully understand what T.E. Lawrence was describing when he wrote, referring to his irregular forces’ tempo and method of operations, “in a real sense, maximum disorder was our equilibrium.”75 If left unchecked, the Houthis’ expanding presence in the Horn of Africa will drive the disorder that they profit from.

Substantive Notes

[a] Losses for Egypt’s economy extend well beyond the loss of revenue from the Suez Canal. Egypt’s farmers are also paying a high cost for the Houthis’ attacks on shipping. Seasonal fruits that are usually shipped to Asian markets are not being shipped. This has caused a glut in some exported fruits as exporters try to reroute shipments to European markets. The loss of revenue from the Suez Canal and from Egypt’s agricultural sector also put pressure on the country’s credit worthiness, which in turn impacts the exchange rate for the Egyptian pound. This, in turn, fuels inflation.

[b] The United States, United Kingdom, and Israel have all carried out air and missile strikes against the Houthis. While the strikes may have diminished the Houthis’ ability to carry out missile attacks, they have not had a significant impact on the group’s capability to launch UAVs. UAVs are easier to conceal and more mobile than missiles. The Houthis routinely move both UAVs and some missiles around the parts of Yemen that they control by commercial trucks. The UAVs are stored and, in some cases, launched from modified intermodal shipping containers, which are ubiquitous in Yemen. The Houthis also use modified fuel tankers to conceal and move both UAVs and missiles. UAV assembly and manufacturing facilities have largely been moved to urban areas that provide civilian cover. Israel’s July and September attacks on fuel storage tanks, port infrastructure, and a power generation facility were more impactful due to the economic damage done to the Houthis. Fuel smuggling and sales produce vital revenue for the Houthis and the patronage networks that they must sustain to maintain power. However, the Israeli counterstrikes on the Houthis also took a toll on Yemen’s vulnerable civilian population. See Eleonora Ardemagni, “Yemen: Why Israel’s Attack Hurt the Houthis More Than U.S. Strikes,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, July 25, 2024.

[c] Following the Houthis’ November 19, 2023, hijacking of the vehicle carrier Galaxy Leader, a significant number of tribes and sections of tribes as well as some members of Islah shifted support to the Houthis. Some elite members of the Murad (Marib-based), Nihm (territory between Sana’a and Marib), Dahm (al-Jawf), and Jadaan (Marib) among others visited Houthi officials to praise their actions. In the weeks after hijacking the Galaxy Leader, the Houthis converted parts of the ship into a mafraj (a place where Yemenis traditionally chew qat, a mild narcotic). Tribal elite and Houthi elite competed with one another for opportunities to visit the ship and chew qat on the vessel. Author interviews, multiple former Yemeni government officials and Yemen-based analysts, September-October 2024.

[d] Goods of all kinds—from luxury cosmetics and handbags to illicit items like silencers—arrive in Sana’a with incredible speed. Wealthy Yemenis as well as elites loyal to the Houthis living in Sana’a routinely order goods from around the world and can usually obtain them within a week, often less. Author interviews, Yemen-based analysts and former government officials, September 2024.

[e] Iran and Hezbollah have a history of operating in Somalia. There is debate about the extent of Hezbollah and Iranian involvement with the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) and later al-Shabaab. A 2006 U.N. report indicated that fighters from Somalia fought with Hezbollah during its 2006 war against Israel. See Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2015) and Andrew McGregor, “Accuracy of New UN Report on Somalia Doubtful,” Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, November 21, 2006.

[f] The Houthis are developing a range of new armed and surveillance UAVs that are made of cheap, durable, and hard to detect materials that include laminated cardboard, carbon fiber and resin, as well as plastic. The Houthis use 3D printers to make and customize parts and fittings for some of their UAVs. Author interviews, Tihama-based security officials, October 2024.

Citations

[1] See Michael Knights, “A Draw is a Win: The Houthis After One Year of War,” CTC Sentinel 17:9 (2024).

[2] ACLED, Yemen Conflict Observatory, Red Sea Attack Dashboard; “US Navy destroys Houthi missiles and drones targeting American ships in Gulf of Aden,” Associated Press, December 1, 2024.

[3] Emanuel Fabian, “Explosive Drone from Yemen hits Tel Aviv apartment building, killing one man, wounding others,” Times of Israel, July 19, 2024.

[4] Nuran Erkul Kaya, “Red Sea trade sees historic decline amid rising tensions in Middle East,” Anadolu Ajansi, July 10, 2024.

[5] “FM to IMO Secretary-General: Egypt suffers losses of $6 billion due to Houthis attacks in Red Sea,” Egypt Today, November 1, 2024.

[6] Thibault Denamiel, Matthew Schleich, William Alan Reinsch, and Wilt Todman, “The Global Economic Consequences of the Attacks on Red Sea Shipping Lane,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, January 22, 2024.

[7] Nick Savvides, “Attacks on Red Sea shipping bankrupt Israeli port,” Seatrade Maritime News, July 10, 2024.

[8] Thomas Newdick, “German Navy Confirms Its Supersized Frigate Will Avoid the Red Sea,” Warzone, November 4, 2024.

[9] “Report: Houthis On Track to Earn $2B a Year by Shaking Down Shipowners,” Maritime Executive, November 4, 2024.

[10] Stacy Philbrick Yadav, “The Houthis’ ‘Sovereign Solidarity’ with Palestine,” Middle East Report Online, January 24, 2024; Gerald M. Feierstein, “Houthis see domestic and regional benefit to continued Red Sea attacks,” Middle East Institute, January 11, 2024.

[11] Abdullah Baabood, “How Gulf States Are Reinterpreting National Security Beyond Their Land Borders,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 1, 2024; Bruce Riedel, “The Houthis have won in Yemen: What next?” Brookings, February 1, 2022; Tyler B. Parker and Ali Bakir, “Strategic Shifts in the Gulf: GCC Defence Diversification amidst US Decline,” International Spectator, October 14, 2024; Thomas Juneau, “Unpalatable Option: Countering the Houthis,” Survival 66:5 (2024): pp. 183-200.

[12] Author interviews, multiple Yemen-based security practitioners and analysts, October-November 2024.

[13] Author interviews, Somalia- and Yemen-based government officials and security practitioners, September-November 2024.

[14] See “UN Security Council letter dated 11 October from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” United Nations, October 11, 2024.

[15] Author interviews, Yemen-based analysts and security practitioners, September 2024.

[16] Nadwa al-Dawasari, “Our Common Enemy: Ambiguous Ties Between al-Qaeda and Yemen’s Tribes,” Carnegie Middle East Center, January 11, 2018; Michael Horton, “Fighting the Long War: The Evolution of al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017).

[17] Michael Horton, “Guns for Hire: How al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula Is Securing Its Future in Yemen,” Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, January 26, 2018.

[18] Author interviews, Yemen-based analysts, September 2024.

[19] Andrea Carboni and Matthias Sulz, “The Wartime Transformation of AQAP in Yemen,” ACLED, December 14, 2020.

[20] Tricia Bacon and Daisy Muibu, “Al-Qaida and Al-Shabaab: A Resilient Alliance,” in Michael Keating and Matt Waldman eds., War and Peace in Somalia: National Grievances, Local Conflict and Al-Shabaab (London: C Hurst & Co Publishers Ltd, 2018).

[21] Dan Joseph and Harun Maruf, Inside al-Shabaab: The Secret History of Al-Qaeda’s Most Powerful Ally (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2018); author interviews, Yemen and Somalia-based analysts, November 2024.

[22] Jay Bahadur, “Terror and Taxes: Inside al-Shabaab’s Revenue Collection Machine,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2022.

[23] “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula: Sustained Resurgence in Yemen or Signs of Further Decline?” ACLED, April 6, 2023.

[24] Author interviews, Yemen-based analysts, September-November 2024.

[25] Author interviews, Yemeni government officials and Yemen-based security practitioners and analysts, September 2024 and October 2024.

[26] Author interview, Yemeni government officials, September 2024; “Integrated Responses to Human Smuggling from the Horn of Africa to Europe,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 2017.

[27] Author interviews, Yemen, Ethiopia, and Somalia-based officials and analysts, September-October 2024.

[28] See “Thirty-fourth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolution 2734 (2024) concerning ISIL (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations, July 22, 2024, p. 14.

[29] Abu Bakr Ahmed, “Al-Qaeda’s Shifting Alliances during the Yemen War,” Sanaa Center for Strategic Studies, October 13, 2023.

[30] Eleonora Ardemagni, “Emirati-backed forces eye Yemen’s energy heartland,” Middle East Institute, August 30, 2022.

[31] Fernando Carvajal, “The Decline of Yemen’s Islamist al-Islah Party,” New Arab, October 12, 2022.

[32] “Al-Qaeda resurgence in Yemen offers fresh threat to stability,” Gulf States Newsletter, June 19, 2022.

[33] “Yemen’s al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base,” International Crisis Group, February 2, 2017.

[34] Ludovico Carlino, “Al-Qaeda’s Strategy in the Yemeni War,” Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 19, 2019; Michael Horton, “Capitalizing on Chaos: AQAP Advances in Yemen,” Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, February 19, 2016.

[35] “Al-Qaeda says swapped prisoners with Houthis: Report,” New Arab, February 20, 2023; “The Curious Tale of Houthi-AQAP Prisoner Exchanges in Yemen,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, December 17, 2021.

[36] Reuben Dass, “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s Drone Attacks Indicate a Strategic Shift,” Lawfare, August 20, 2023.

[37] Author interviews, Yemen-based security officials, October 2024.

[38] See Assim al-Sabri, “How the Gaza Crisis Could Bring Iran and Al-Qaeda in Yemen Together,” Sanaa Center, December 11, 2023.

[39] Chiara Gentili, “Countering the arms race in Somalia,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, May 23, 2024; David Willima, “An ocean of weapons: arms smuggling to Somalia,” Institute for Security Studies, February 7, 2023.

[40] Michael Horton, “Yemen: A Dangerous Regional Arms Bazaar,” Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, June 16, 2017.

[41] Author interviews, Somalia and Yemen-based analysts and government officials, October 2024.

[42] Michael Knights, “The Houthi War Machine: From Guerrilla War to State Capture,” CTC Sentinel 11:8 (2018).

[43] Author interviews, former Yemeni government officials and Yemen-based security practitioners, September 2024.

[44] Andrew Black, “Weapons for Warlords: Arms Trafficking in the Gulf of Aden,” Terrorism Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, June 18, 2009.

[45] Author interview, Yemen-based analysts, October 2024.

[46] Author interviews, Somalia and Yemen-based analysts, September-October 2024.

[47] Author interviews, Somalia and Yemen-based security practitioners, August 2024.

[48] Thomas Harding, “The Houthis have built their own drone industry in Yemen,” National, June 13, 2020; “Yemen’s Houthis manufacture new ballistic missiles, drones,” Middle East Monitor, July 8, 2019.

[49] “Seized at Sea: Iranian Weapons Smuggled to the Houthis,” Defense Intelligence Agency, April 30, 2024.

[50] “Assessment of the Response to Illicit Weapons Trafficking in the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea,” United Nations Global Maritime Crime Programme, 2024.

[51] Author interviews, Yemeni security officials based in the Tihama region, October 2024.

[52] Author interview, Somalia and Somaliland-based government officials and security practitioners, October-November 2024.

[53] Author interview, Yemeni government official, October 2024.

[54] See “Ra’s al `Arah: Ethiopian migrants’ path to hell,” Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, 2019.

[55] “Iran: Enabling Houthi Attacks Across the Middle East,” Defense Intelligence Agency, February 2024.

[56] See Andreas Krieg and Jean-Marc Rickli, Surrogate Warfare: The Transformation of Warfare in the Twenty-First Century (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2019); Michael Eisenstadt, “Iran’s Gray Zone Strategy: Cornerstone of it Asymmetric Way of War,” PRISM 9:2 (2021).

[57] Samia Nakhoul and Parisa Hafezi, “Iranian and Hezbollah commanders help direct Houthi attacks in Yemen,” Reuters, January 20, 2024.

[58] “Yemen’s Torture Camps: Abuse of Migrants by Human Traffickers in a Climate of Impunity,” Human Rights Watch, May 2014; “Transit in Hell,” Mwatana for Human Rights, December 18, 2023.

[59] Author interview, Yemen and Ethiopia-based researchers, September 2024.

[60] “Under the Shadow: Illicit Economies in Iran,” Global Initiative against International Crime, October 2020; “Houthis Accused of Turning Yemen into Drug Hub in Illicit Trade Worth Billions of Dollars,” Asharq al-Awsat, June 30, 2023.

[61] Author interview, Yemen-based analyst, October 2024.

[62] Caroline Rose and Karam Shaar, “The Captagon Trade from 2015 to 2023,” New Lines Institute, May 30, 2024; Hesham Alghannam, “Border Traffic: How Syria Uses Captagon to Gain Leverage Over Saudi Arabia,” Carnegie Middle East Center, July 9, 2024.

[63] Author interview, senior aide to Major General Tariq Saleh, November 2024.

[64] Author interview, Yemen and UAE-based security analysts, October 2024.

[65] See Victoria Cheng, “Case Study on smuggling sensitive U.S.-origin items through Chinese front companies to Iranian military entities,” Institute for Science and International Security, August 12, 2024; “Treasury Targets Sanctions Evasion Network Moving Billions for Iranian Regime,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, March 9, 2023; Kimberly Donovan, Maia Nikoladze, Ryan Murphy, and Yulia Bychkovska, “Global Sanctions Dashboard: How Iran evades sanctions and finances terrorist organizations like Hamas,” Atlantic Council, October 26, 2023.

[66] Figure 2 is based on research conducted by the author during 2023.

[67] See Matthew Levitt, Hezbollah: The Global Footprint of Lebanon’s Party of God (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2015).

[68] Ibid.

[69] Ibid.

[70] Author interviews, Yemeni expatriates and Ethiopia and Djibouti-based officials and security analysts, October-November 2024.

[71] Hesham Al-Mahya, “How the Houthis’ alternative economy is worsening Yemen’s humanitarian crisis,” New Arab, May 2, 2024; Eleonora Ardemagni, “The Houthi’s Economic War Threatens Lasing Peace in Yemen,” Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, June 15, 2023; Saeed al-Batati, “Houthis pocket millions of dollars of public funds say UN experts,” Arab News, March 2, 2023.

[72] Gary Dixon, “Houthis Extort 2 Billion from Ship Owners in Red Sea Racket, UN Told,” TradeWinds, November 5, 2024.

[73] Author interviews, Yemen-based officials and analysts, October 2024.

[74] Author interviews, Yemen and United Arab Emirates-based analysts, October 2024.

[75] Thomas Edward Lawrence, “The Evolution of a Revolt,” Combat Studies Institute (CSI), US Army and General Command Staff College, 1920.