The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

- Russia. Russia used the first Russia-Africa Ministerial Summit to continue pushing narratives and securing deals that advance its strategic objective of undermining the Western-led international system and highlighting its stature as a global power in Africa. The Kremlin advanced its vision of Russia as the leader of an anti-Western bloc seeking a multipolar world order and highlighting the narrative that Russia is not internationally isolated. Russia also discussed increasing cooperation in several sectors including finance, nuclear energy, satellite technology, and security. These partnerships aim to boost Russian influence and its image as a great power at the expense of Western economic, political, and security interests.

- Nigeria. Salafi-jihadi groups based in the Sahel are increasingly infiltrating northwestern Nigeria, likely with the long-term objective of establishing support cells that can coordinate with their Nigeria-based affiliates to fundraise and possibly carry out major attacks. Salafi-jihadi cells in northwestern Nigeria would likely serve as a rear support zone and facilitation hub for the affiliates’ centers of gravity in the Sahel and northeastern Nigeria. Stronger links between the groups would help the affiliates pool resources for major attacks, including outside their typical areas of operation in neighboring countries or even Europe.

- Somalia. The SFG is increasingly at odds with the Jubbaland state government in southwestern Somalia over disputed election reforms, increasing the risk of political violence or a regional proxy war in Somalia that would undermine Western security interests in the Horn of Africa. The fighting between the Somali Federal Government (SFG) and Jubbaland forces would likely be limited, but the political standoff between Egypt and Ethiopia over Somalia may exacerbate local tensions and escalate violence if the regional players back Somali actors as proxies. A breakdown in security in Jubbaland could provide opportunities for al Shabaab to strengthen its de facto statelet in southern Somalia, which would negatively affect Western counterterrorism interests in the Horn of Africa and threaten the surrounding region due to al Shabaab’s links to the Iran-backed Yemeni Houthis.

- Assessments:

Russia

Russia used the first Russia-Africa Ministerial Summit to continue pushing narratives and securing deals that advance its strategic objective of using Africa to undermine the Western-led international system and highlight its stature as a global power. Russia hosted the first Russia-Africa Ministerial Summit in Sochi on November 9 and 10. Russian officials reported that 54 countries sent delegations.[1] The summit aimed to build on last summer’s Russia-Africa summit, which featured African heads of state.[2] Russian and African officials discussed a wide range of bilateral cooperation including agriculture, defense, education, energy, investment, medicine, mining, political cooperation in international bodies, science, and trade.

Russia continued advancing its vision of Russia as the leader of an anti-Western bloc seeking a multipolar world order and highlighting the narrative that Russia is not internationally isolated. The joint statement adopted at the end of the summit included several points of Vladimir Putin’s plan for a “new world order” that draws on Russian narratives targeting the West.[3] Putin sees himself as the “voice” of the “global majority” that composes this new order.[4] The statement emphasized the importance of respecting sovereignty, alluding to a popular narrative across parts of Africa and Russia that the West infringes on sovereignty through paternalistic policies and coercive sanctions.[5] The statement repeatedly refers to equality, inclusivity, and a just international order, implicitly advancing the narrative of the need for a more multipolar system.[6] The joint statement explicitly outlines steps to preserve the historical memory of the colonial era and condemns neocolonial practices, indirectly highlighting Russia’s status as a non-colonial alternative and fueling anti-Western sentiment.[7]

Russian officials and media attacked the West more explicitly during and after the summit. Russia’s foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, said that a point of emphasis throughout the summit was the need to grow bilateral cooperation to decrease dependence on Western-led global mechanisms and advance toward a more multipolar world.[8] Russia’s Africa Corps–affiliated outlet Africa Initiative said that the summit showed Russia is not isolated and that the “Global South” supports Russia and not the “collective West.”[9] Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova said the conference “dashed dirty hopes” of isolating Russia.[10] Russian officials and media repeatedly attacked Western sanctions and accused sanctions of destroying globalization and inhibiting business and medical cooperation with Africa.[11]

These statements double down on Russia’s narratives from the recent BRICS forum in Kazan, Russia, in October. The Kremlin directed Russian media to similarly frame the BRICS forum as a sign that Putin is the “informal lead of the world majority” and that the West’s “attempts to isolate” Russia have failed.[12] Russian media highlighted Russia’s cooperation through BRICS and the Russia-Africa summit as strategic and multifaceted as opposed to the West’s “fleeting alliances.”[13] The joint statement at the end of the summit repeatedly emphasized the “strategic” nature of Russia-Africa cooperation, while Putin and Lavrov emphasized Russia’s “total support” across “all axes.”[14] Russia’s framing of the Russia-Africa summit also borrows from China’s narratives surrounding engagement with BRICS and the “Global South.” China has framed itself as the leader of the “Global South” and emphasized the importance of institutions like BRICS in developing alternative mechanisms that push for a more multipolar and less Western-dominated system.[15]

African countries have repeatedly signaled their preference for diversifying and balancing ties with China, Russia, and the West over choosing sides, which undermines the Kremlin’s goals to form an anti-Western bloc. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said after the BRICS summit that South Africa did not view “any particular country or bloc of countries as the enemy,” only friends, and that nonalignment with diverse partnerships is better than domination by any one country.[16] South Africa has demonstrated this stance by quietly stymying Russia’s efforts to transform BRICS into an explicitly anti-Western bloc.[17] African leaders have repeatedly stated this desire to work with all willing partners and to diversify cooperation without choosing sides in geopolitical rivalries.[18]

Russia discussed nuclear energy and space cooperation with several countries, two sectors that expand Russian influence while undermining the West’s economic, political, and security interests in Africa. Russia and Rwanda discussed plans to increase nuclear energy education and training.[19] Rwanda signed a memorandum of understanding with the Russian state nuclear energy company Rosatom in 2018 that laid the groundwork for a subsequent deal in 2019 to build a nuclear science center.[20] Rwanda has more recently signed memorandums of understanding with the Canadian-German company Dual Fluid Energy in 2023 to build a test nuclear reactor and the US firm NANO Nuclear in August 2024 to construct mini reactors in Rwanda.[21] Angola signed a memorandum of understanding “in the space industry,” expanding on preexisting collaboration with the Russian space manufacturer Energia that helped Angola manufacture and launch two satellites into orbit in 2017 and 2022.[22]

Figure 1. Russian Nuclear Cooperation in Africa

Source: Liam Karr; European Parliament

Russia’s emphasis on nuclear and space cooperation has helped expand its influence on the continent. Russia has positioned itself as a global leader in the nuclear energy market, including in Africa.[23] Russia has signed dozens of agreements on nuclear energy cooperation, including recent deals to construct nuclear power plants in Burkina Faso and Mali.[24] Russia has slowly grown cooperation surrounding satellite technology since the 2010s. It partnered with Egypt, Angola, and Tunisia to launch their first satellites in 2014, 2017, and 2021, respectively. Glavcosmos, a subsidiary of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, has signed several deals with Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger since 2023 to provide them with satellite technology.[25]

These deals create multiple revenue and export-market opportunities for the Kremlin. Nuclear cooperation enables Russia to export nuclear energy technology, secure power plant construction projects, and sell the fuel that the power plants need to operate.[26] Satellite technology similarly provides opportunities for entities like Roscosmos and Energia.[27]

Russia’s nuclear projects on the continent come at the expense of Western economic and political interests. Russia’s nuclear projects create African dependence on Russia, strengthening the Kremlin’s long-term influence in Africa. Nuclear power plants will rely on Russian experts to operate and maintain the plants or on the Russian training of an initial group of domestic experts. Russia has emphasized education and training initiatives to create this self-reliance, but countries will continue to be reliant on Russia for nuclear fuel, which has caused dependency problems for European countries.[28]

The West is missing out on the political influence that comes with supporting Africa’s space efforts to the detriment of political influence and national security concerns. The United States used space diplomacy during the Cold War to signal its commitment to the continent and help dictate international norms on space, but the continent is now turning to countries like China and Russia in the West’s absence.[29] This shift risks enabling China and Russia to dictate international positions on data sharing, safety coordination, and other international space norms.[30] China and Russia can also use this cooperation to strengthen their surveillance capacities in the many cases in which they construct and launch the satellites for their African partners.[31]

Russia laid out plans to increase human ties to the continent, which increases its diplomatic footprint and soft-power influence. Russian media reported that the Kremlin plans to open embassies in Comoros, Gambia, Liberia, and Togo.[32] Russian media has said throughout 2024 that the Kremlin plans to open embassies in Niger, South Sudan, and Sierra Leone.[33] The Kremlin aims to grow more informal human network ties to Russia by increasing air links with Africa and increasing the number of African students studying at Russian universities.[34] Russia reached agreements with the Central African Republic (CAR) and Rwanda to implement visa-free travel for some officials.[35]

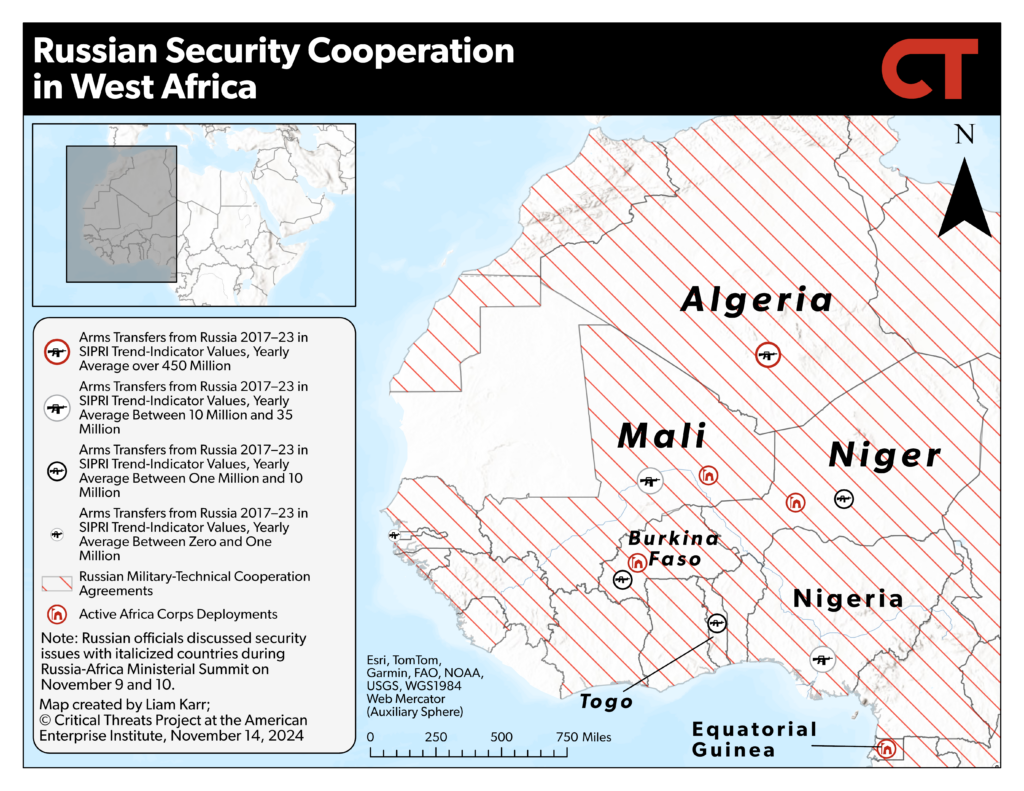

The Kremlin continued to highlight its role as a security provider on the continent, advancing its efforts to expand its military influence and perception as a great power at the West’s expense. Russian leadership highlighted the “export of security” as a theme of the conference, and Putin’s opening remarks and a joint statement adopted at the end of the conference heavily emphasized the importance of anti-terrorism cooperation.[36] The concluding joint statement announced plans to set up a dialogue mechanism to coordinate efforts on multiple security-related issues.[37]

Russian officials held bilateral discussions with some security partners. The Sudanese deputy foreign minister reiterated that Sudan is still interested in following through on its agreement to build a Russian naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea coast in Port Sudan. Mikhail Bogdanov, the Russian deputy foreign minister and special representative for the Russian president in Africa and the Middle East, met with Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) officials in April 2024 to revive a stalled 2017 agreement for the naval base in exchange for “unrestricted qualitative military aid,” but the SAF has yet to ratify and implement the deal.[38] Russian officials separately met with their counterparts from Algeria, Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, and Togo to discuss security issues during the summit.[39] These countries are key to Russia’s defense footprint across West Africa, where thousands of Russian Africa Corps forces are supporting the Sahelian governments at the epicenter of the region’s Salafi-jihadi insurgency. Russia has increased cooperation with Togo in recent years as it faces the spillover of the insurgency, while its joint operations with Malian forces near the Algeria-Mali border have strained its historically strong relations with Algiers.[40]

Russian officials announced plans to open trade missions in Senegal and Tanzania, which will help connect Russia’s network in the landlocked central Sahel to the sea. The trade missions specifically seek to gain access to Senegalese and Tanzanian ports.[41] Russia’s use of Cameroonian ports as a key logistic hub for its imports and exports to the CAR provide a template for how Africa Corps would use Senegalese ports as hubs for activity in Mali.[42]

Figure 2. Russian Security Cooperation in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

Russia’s growing security footprint has come at the expense of Western interests. The Kremlin positioned itself as an alternative security partner to the Sahelian juntas, which contributed to their decisions to expel French and US forces pursuing counterterrorism objectives against al Qaeda (AQ) and Islamic State affiliates in the Sahel.[43] The insurgents have only strengthened since Russian forces arrived and are now carrying out attacks near the Malian and Nigerien capitals.[44] A Russian naval base in Sudan would enable the Kremlin to better challenge the West in the Red Sea and adjacent theaters such as the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean in the event of a broader conflict.

Russia used the summit to amplify narratives villainizing Ukraine. Russia accused Ukraine of supporting terrorism in Africa and amplified statements from Mali and the chairman of the West African regional economic bloc, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) accusing Ukraine of state-sponsored terrorism in Mali.[45] Niger and Mali cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine after Ukrainian officials implied they aided non-jihadist Tuareg rebels in an attack in northern Mali in July that killed at least 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers.[46] Ukraine’s military intelligence spokesperson said “the [non-jihadist] rebels received the necessary information, and not just information” to enable the successful attack.[47] However, the Ukrainian government has since denied these claims.[48] The Associated Press, CTP, and Radio Free Liberty/Radio Europe all assessed in that case that the fighters involved in the ambush had ties to both AQ’s Sahelian affiliate and the non-jihadist Malian Tuareg rebel coalition.[49] Non-Russia-aligned actors like Senegal and ECOWAS that have strained ties to the pro-Russian juntas also condemned any foreign interference.[50]

Nigeria

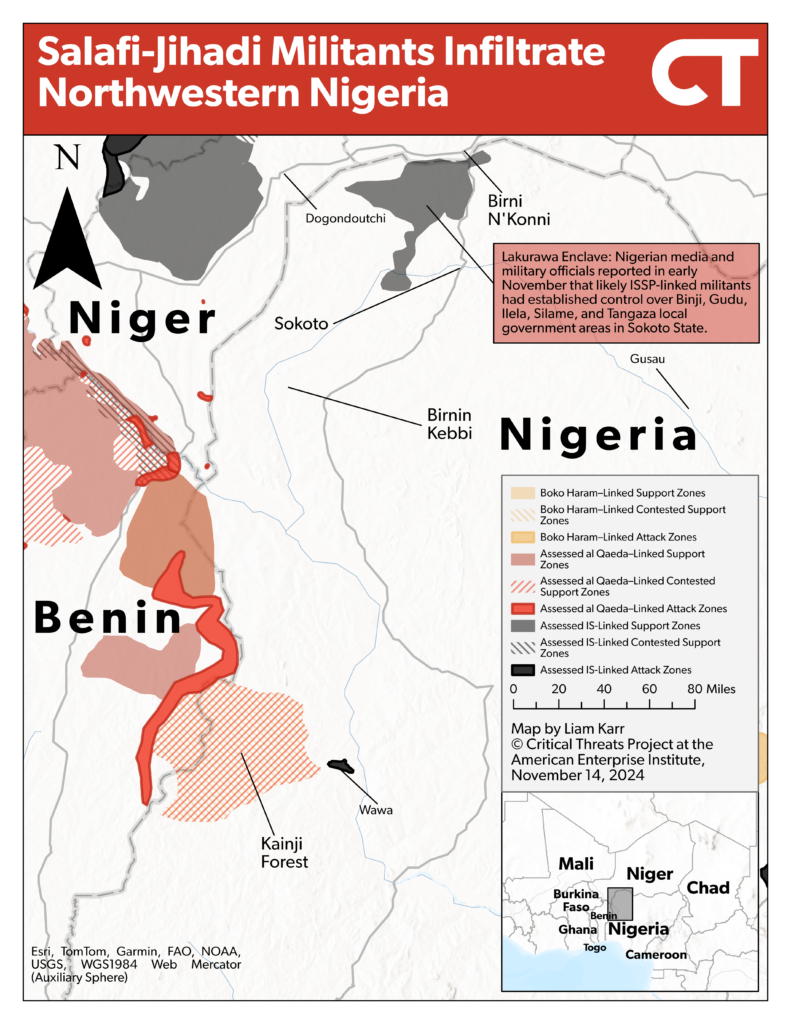

Salafi-jihadi groups based in the Sahel are increasingly infiltrating northwestern Nigeria, likely with the long-term objective of establishing support cells that can coordinate with their Nigeria-based affiliates and create fundraising opportunities. Nigerian military officials sounded the alarm in early November that IS-linked Salafi-jihadi insurgents locally referred to as “Lakurawas” had increasingly infiltrated northwestern Nigeria’s Kebbi and Sokoto states from neighboring Niger and Mali.[51] Nigerian media reported that the insurgents control some communities across five districts in Sokoto state, which borders Niger.[52] The insurgents have imposed their harsh interpretation of shari’a law and taxed communities in these areas.[53] Military officials linked the Lakurawa resurgence to the deteriorating security situation in the Sahel and a decrease in Niger-Nigeria joint operations following the July 2023 Niger coup.[54]

The Lakurawa faction is not new and had previously tried to infiltrate Nigeria in 2018. This previous iteration of this group embedded itself into communities in Sokoto state in late 2018.[55] It alienated the local population, however, after attempting to impose shari’a and excessively taxing the locals, and a joint Nigerian-Nigerien military operation pushed the militants back across the border by early 2019.[56] Researchers Jake Barnett and Murtala Ahmed Rufa’i assessed in 2023 that the faction is affiliated with IS Sahel Province (ISSP) due to their movement patterns and tribal ties.[57]

Figure 3. Salafi-Jihadi Militants Infiltrate Northwestern Nigeria

Source: Liam Karr.

Salafi-jihadi–linked militants have already infiltrated northwestern Niger farther south along the Beninese border in recent years. Multiple researchers have reported that militants with loose suspected links to the Boko Haram offshoot Darul Salam and AQ’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) have embedded themselves in the Kainji forest area since at least 2021.[58] The Dutch research institute Clingendael reported in June 2024 that the militants in Kainji were linked to an increase in bandit-related incidents along the Beninese-Niger border, signaling potential ties to Darul Salam, given the faction’s ties to bandit groups, or JNIM, given that it is the dominant group in Benin.[59] The Nigeria-based IS West Africa Province (ISWAP) claimed an attack on a prison in this area in late 2022, however, suggesting that it is also present in the area or that the militants there have fluid affiliations and may have cooperated on the attack.[60] Ansaru, a small AQ-linked Boko Haram offshoot that has been publicly dormant since 2022, is also active near this area.[61]

Salafi-jihadi cells in northwestern Nigeria likely serve as a rear support zone for the affiliates’ centers of gravity in the Sahel and northeastern Nigeria. Rear support zones in northwestern Nigeria could help facilitate and coordinate activity and resources between AQ and IS affiliates. A UN report in June 2024 stated that ISWAP established cell and facilitation networks in northwestern Nigeria with the express aim of supporting ISSP operations at the behest of IS core leadership.[62] The UN report said that these networks help move weapons, fuel, equipment, and fighters to ISSP in Burkina Faso and Mali, and that cells in Sokoto state play a particularly pivotal role.[63] Local researchers have cast doubt on the report given that the existence of such deep support networks has not come up in interviews with defectors, indicating that it would be a new development if the UN report is accurate.[64] However, researcher Vincent Foucher reported that ISWAP defectors have previously claimed that ISWAP and ISSP sent cadres back and forth to each other.[65] IS supporters claimed that Nigerian fighters traveled to Mali in 2022 to support ISSP as it launched offensives against JNIM and pro-government militia groups.[66]

AQ and IS hubs in northwestern Nigeria would create opportunities for fundraising.[67] Nigerian media have already linked IS to a regional smuggling network that runs through a town on the Niger-Nigeria border in Kebbi state.[68] Local reports of Lakurawa taxation indicate that IS is extracting resources from their areas of operation. The increase in bandit-related activity near the Beninese border in areas with suspected JNIM presence signals that the cells there are generating revenue through criminal activities such as kidnapping prominent local figures for ransom and cattle rustling.[69]

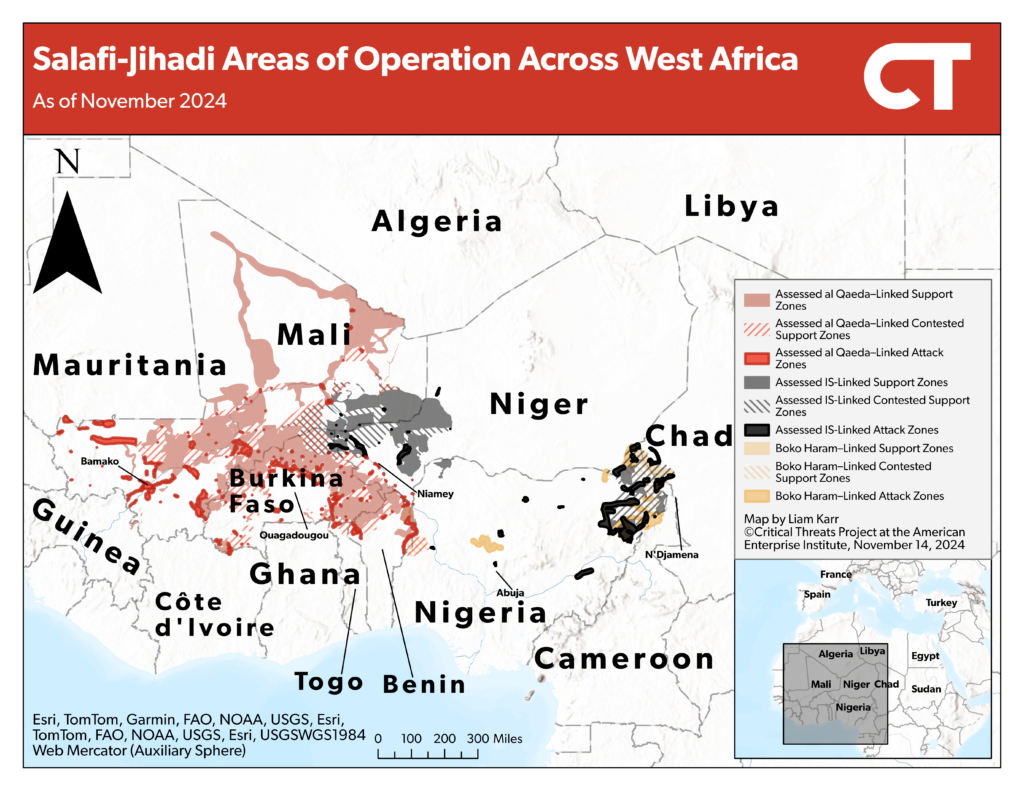

Figure 4. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation Across West Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

Greater links between the groups would help the affiliates pool resources for major attacks. These operations could target areas outside their typical areas of operation, including Europe. JNIM has previously converted rear support zones to attack zones opportunistically or in response to security pressure. JNIM used support zones in Benin and Togo to increase attacks against both governments in response to heightened counterinsurgency activity in 2022, for example.[70] The cells in northwestern Nigeria have also demonstrated their willingness to cooperate for spectacular attacks in Nigeria. The Islamic State claimed two major attacks in central and northwestern Nigeria in 2022—an attack on the Kuje prison near Abuja in July 2022 and an attack on the Wawa cantonment near Kainji Lake in October 2022.[71] Researchers believe that militants with links to Ansaru, Darul Salam, and non-jihadist bandit factions played various roles in both attacks.[72] Darul Salam fighters cooperated with bandits and potentially with Ansaru-linked fighters in March 2022 to abduct dozens of passengers from a train that runs from the northern city of Kaduna to Abuja.[73]

Greater coordination between ISSP and ISWAP would benefit IS’s external attack plot apparatus, including in Europe. IS coordinates external activity through its General Directorate of Provinces. The General Directorate of Provinces has regional offices that help coordinate this activity on the regional level.[74] ISWAP hosts the West Africa office, Maktab al Furqan, which oversees ISSP and ISWAP.[75] IS has repeatedly used these regional offices to coordinate resources from multiple provinces to fund, recruit, or otherwise facilitate external activity.[76]

Greater coordination will help Maktab al Furqan pool its resources and link the office to ISSP’s trans-Saharan facilitation networks. ISSP’s location along migration and smuggling routes that run north to Europe positions it to support activity in Europe. Spain disrupted an IS cell operating out of Morocco and Spain in 2021 that had links to ISSP, IS Khorasan Province in Afghanistan, and IS cells in the Middle East and Europe.[77] Security forces would presumably crack down on the cells in northwestern Nigeria if it supported high-visibility attacks, however, which disincentivizes IS from using the area for attack purposes given it would dilute the area’s utility as a rear support zone.

Competition in northwestern Nigeria could fuel the inter-jihadi rivalry between AQ and IS for supremacy in West Africa. ISSP and JNIM are clashing less frequently in the Sahel since 2023, when the two groups were fighting for supremacy in the Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger border area in the Sahel.[78] Another battle for dominance in northwestern Nigeria could spark similar violence. IS would presumably view a strong JNIM presence in the Benin-Niger-Nigeria border area as a buffer to future IS expansion, similar to how JNIM’s dominance across most of Burkina Faso and Mali is a major reason ISSP is unable to expand farther west. Meanwhile, IS has largely established itself as the dominant actor in Nigeria, which is a bulwark against AQ influence in Africa’s most populous country. AQ or IS linking Nigeria and the Sahel would provide a major propaganda boon for either group to highlight its credentials as the leaders of global jihad in West Africa.[79]

Somalia

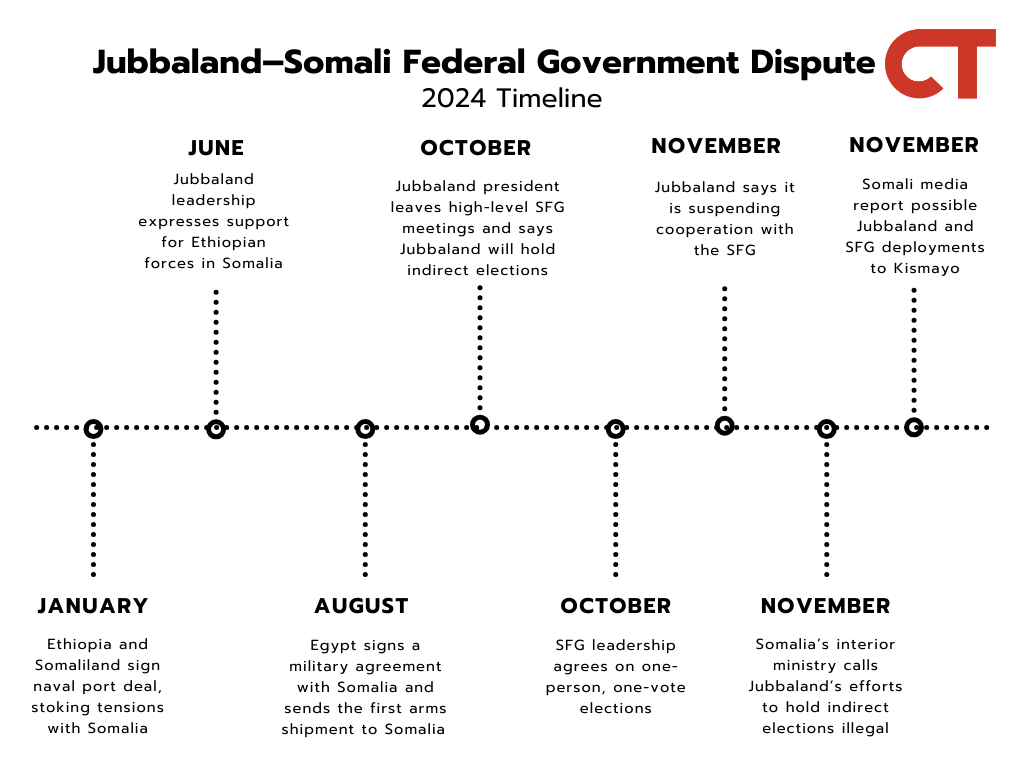

The SFG is increasingly at odds with the Jubbaland state government in southwestern Somalia over disputed election reforms, increasing the risk of political violence in Somalia. The Somali Federal Government (SFG) and three of the five federal member states agreed on a one-person, one-vote election system in late October after monthlong talks under the National Consultative Council. Jubbaland and Puntland states both protested the decision and said they would hold their own elections.[80] Jubbaland President Ahmed Mohamed Islam, also known as Madobe, withdrew from the October council meetings, said the new system would undermine Jubbaland’s regional autonomy, and accused Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud of attempting to extend his term.[81] Madobe plans to run for a third term as the Jubbaland president, after the Jubbaland parliament abolished term limits for the upcoming elections.[82]

The Jubbaland government said on November 10 that it suspended cooperation with the SFG over the SFG reform.[83] MPs from Jubbaland voiced opposition to the SFG’s election plans during a meeting in the Jubbaland state capital, Kismayo, on November 9 and said the SFG was “stoking tribal conflict” against Jubbaland and Puntland. Puntland had already cut ties with the SFG in April.[84] Jubbaland also accused the SFG of obstructing counterterrorism efforts in Jubbaland by neglecting operations in the state and failing to rotate out SFG forces.[85]

Figure 5. Jubbaland–Somali Federal Government Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

The political dispute could lead to limited political violence between the SFG and Jubbaland as Jubbaland plans to hold indirect elections over the coming weeks.[86] The SFG condemned Jubbaland’s decision to hold indirect elections. The SFG interior ministry called Madobe’s actions “illegal” and said Madobe’s term expired in August 2023.[87] The SFG seeks to delegitimize Madobe and his government to provide a justification for intervening in the Jubbaland elections. Somali media reported on November 12 that the SFG may deploy troops to Kismayo to influence Jubbaland elections, according to unspecified sources.[88] Somali media said that Jubbaland forces have deployed to Kismayo airport reportedly to obstruct the Somali prime minister from traveling to the state ahead of elections, although controlling the airport also denies the SFG the ability to deploy additional troops in Kismayo.[89] Troops loyal to the SFG and Jubbaland previously clashed in early 2020 after a disputed election in Jubbaland in 2019.[90]

The fighting between the SFG and Jubbaland forces would likely be limited. The SFG and Jubbaland forces clashed for approximately a month during the last election dispute, between February and March 2020. The clashes were limited in scope, with violence occurring in only the Gedo region. The fighting ended in June 2020, when the SFG recognized Madobe as the interim president of Jubbaland.[91]

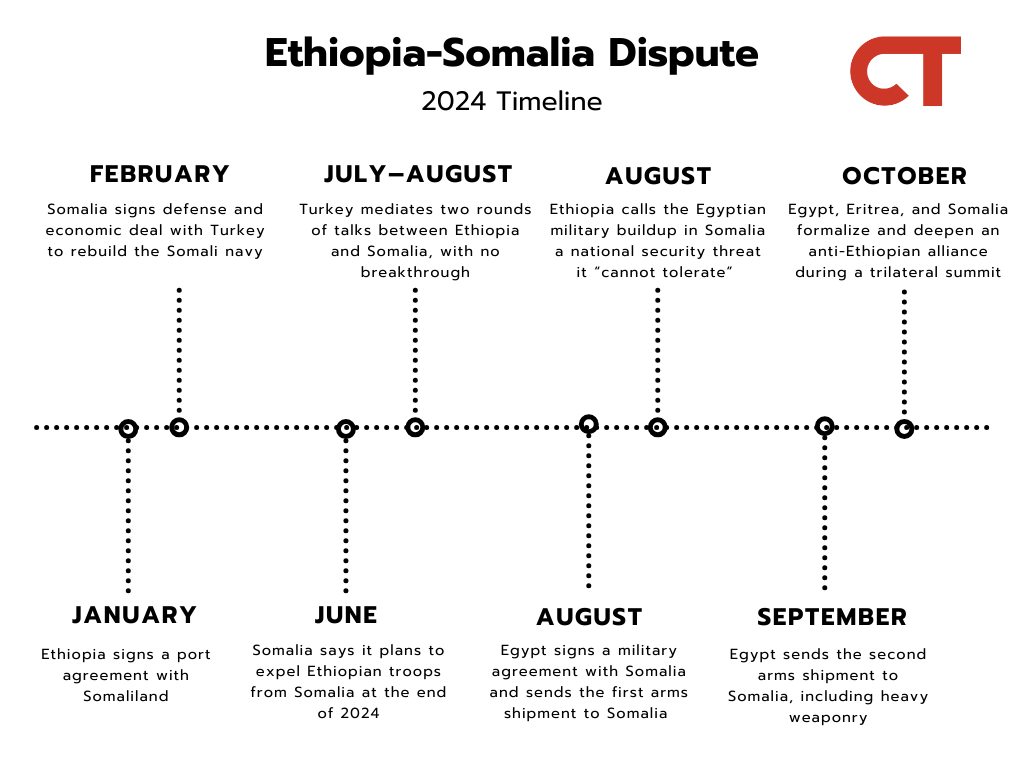

The political standoff between Egypt and Ethiopia over Somalia may exacerbate local tensions and escalate violence if Egypt or Ethiopia backs Somali actors as proxies. Relations between Ethiopia and the SFG have deteriorated since January 2024, when Ethiopia signed a naval base agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region.[92] Mohamud has repeatedly called the agreement a threat to Somalia’s territorial integrity and insisted that Ethiopian troops will be replaced by Egyptian forces in the new African Union (AU) mission in 2025.[93] Egypt has sent heavy weapons to Somalia after signing defense deals in August and plans to deploy up to 10,000 troops to Somalia as part of the AU mission and separate bilateral cooperation.[94] Ethiopia has called the Egyptian buildup and its removal from the AU mission national security threats, especially in light of Egypt’s saber-rattling over Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam as an “existential threat” to its Nile water supply.[95]

Figure 6. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute

Source: Liam Karr and Kathryn Tyson.

External backing helped stalemate the conflict in 2020. The strong Ethiopian presence in the disputed region of Jubbaland in 2020 dissuaded Jubbaland and its Kenyan backers from expanding violence into the disputed region as long as they maintained control over the state government.[96] Meanwhile, the SFG and its Ethiopian partners were content with their de facto control over the disputed region and preferred freezing the conflict to angering Kenya.[97]

Somali factions and their external backers are more polarized in 2024, however, increasing the risk that external intervention will cause violence. Ethiopia and Jubbaland are now on the same side due to Jubbaland’s stated preference for Ethiopian troops to remain in Somalia and both parties’ general opposition to the SFG.[98] The SFG is presumably unwilling to accept the current de facto state of play with a rogue state government that would allow a continued Ethiopian presence, and its Egyptian partner has repeatedly signaled its desire to support the SFG’s “sovereignty” and its opposition to Ethiopia.[99] Any SFG and Egyptian effort to interfere in Jubbaland would threaten the Jubbaland regime and undermine Ethiopia’s military presence in Somalia, which Ethiopia has highlighted as a national security concern.[100] A Kenyan delegation reportedly met with Madobe on November 4 to ease tensions between Jubbaland and the SFG, however.[101]

Infighting would provide opportunities for al Shabaab to strengthen its de facto statelet in southern Somalia, which would negatively affect Western counterterrorism and regional security aims in the Horn of Africa. Jubbaland has long been a hotbed of al Shabaab activity in Somalia[102] The Middle Jubba region, one of the three regions of Jubbaland, is al Shabaab’s center of gravity. Al Shabaab maintains leadership headquarters and openly governs towns in this region.[103] Jubbaland’s state capital, Kismayo, is a major port city, making the state strategically significant for both al Shabaab and government forces. Al Shabaab maintains an attack zone in Kismayo and has regularly conducted attacks throughout the state over the past year.[104] The SFG was unable to expand its 2022 offensive against al Shabaab in central Somalia to the group’s main havens in southern Somalia, where clan rivalries and grievances against al Shabaab have not mobilized locals to combat the group.[105] Al Shabaab also launched several large-scale attacks in 2023 to overrun Somali bases designated for operations into Middle Jubba.[106]

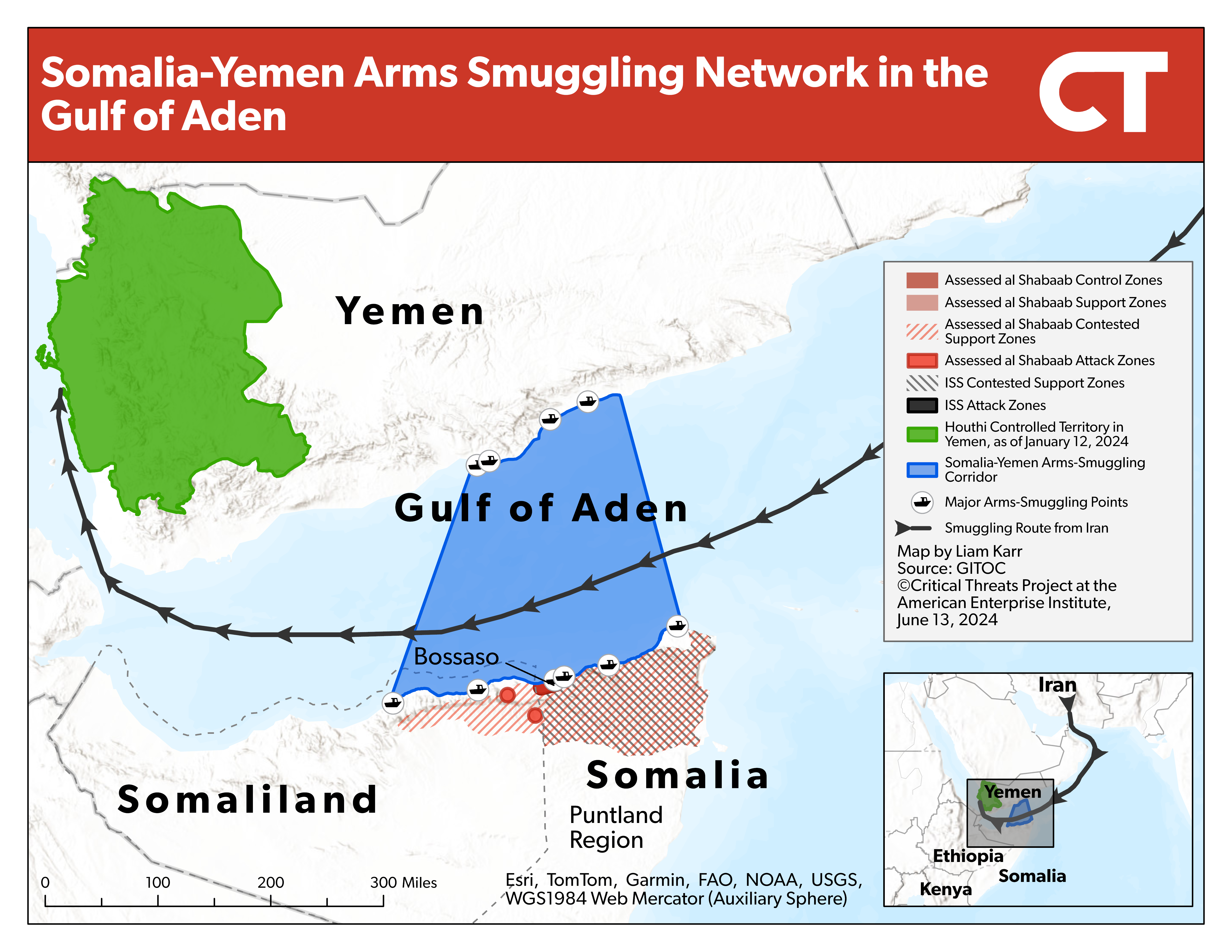

Al Shabaab strengthening in southern Somalia would presumably benefit its ongoing outreach to the Iran-backed Houthi militants, threatening critical waterways off the northern Somalia coast. US intelligence officials claimed in June 2024 that the Houthis and al Shabaab discussed a deal for the Houthis to provide weapons to al Shabaab.[107] The UN reported in October that the Houthi outreach to al Shabaab aims to extend the Houthis’ area of operations and enable them to carry out attacks at sea from the northern Somali coast.[108] The UN report stated that the Houthis had increased small arms and light weapons shipments to al Shabaab.[109] CTP previously assessed in June that the two groups are likely interested in exchanging higher-grade systems such as surface-to-air missiles or attack drones given US intelligence reports and both groups’ preexisting access to small and light arms via the illicit Somalia-Yemen arms trade.[110]

Figure 7. Somalia-Yemen Arms Smuggling Network in the Gulf of Aden

Source: Liam Karr; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.