In June 2024, fighters from the Katiba Serma sub-group of Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) redoubled their efforts to cut off the town of Boni, in the Mopti region of central Mali.1 This is the latest iteration of a blockade that the jihadist group had intermittently imposed for more than nine months on the Route Nationale (RN) 16.2 Blockades are very much part of JNIM’s toolkit in its areas of influence not just in Mali, but also in neighbouring Burkina Faso.

Until June, some Boni residents had been able to negotiate passage in and out of the town on an ad hoc basis, but their ability to move was unpredictable and extremely constrained, generating profoundly negative consequences for the local economy. However, on 25 May, JNIM signalled that an intensification of the blockade was coming. The group sent messengers into the town warn residents that they believed some locals were collaborating with the security forces.3

This belief stemmed from the fact that Mali’s military had recently established a base in Boni, hosting Russia’s Africa Corps alongside its own soldiers.4 According to an aid worker, JNIM’s leadership became convinced that collaboration between civilians and soldiers at the camp explained the loss of several local leaders in unexpected strikes.5

A few days after the message was delivered, JNIM made good on its threats. Reports have emerged of the group robbing passengers arriving in buses and cars of all their money and belongings as they attempted to enter Boni, and an aid worker reported that JNIM had even seized vehicles from civilians attempting to enter the area.6 An academic researcher from the area confirmed that local extortion had worsened substantially since May.7

Truck drivers have also been seriously affected by these developments. On 18 June, four trucks were torched by JNIM on the RN16 near Boni.8 Some civilians reportedly still travel to JNIM bases in the bush near Boni to negotiate movement, including into town. However, this hardly guarantees their protection, since such movements risk attracting the suspicions of the military.9

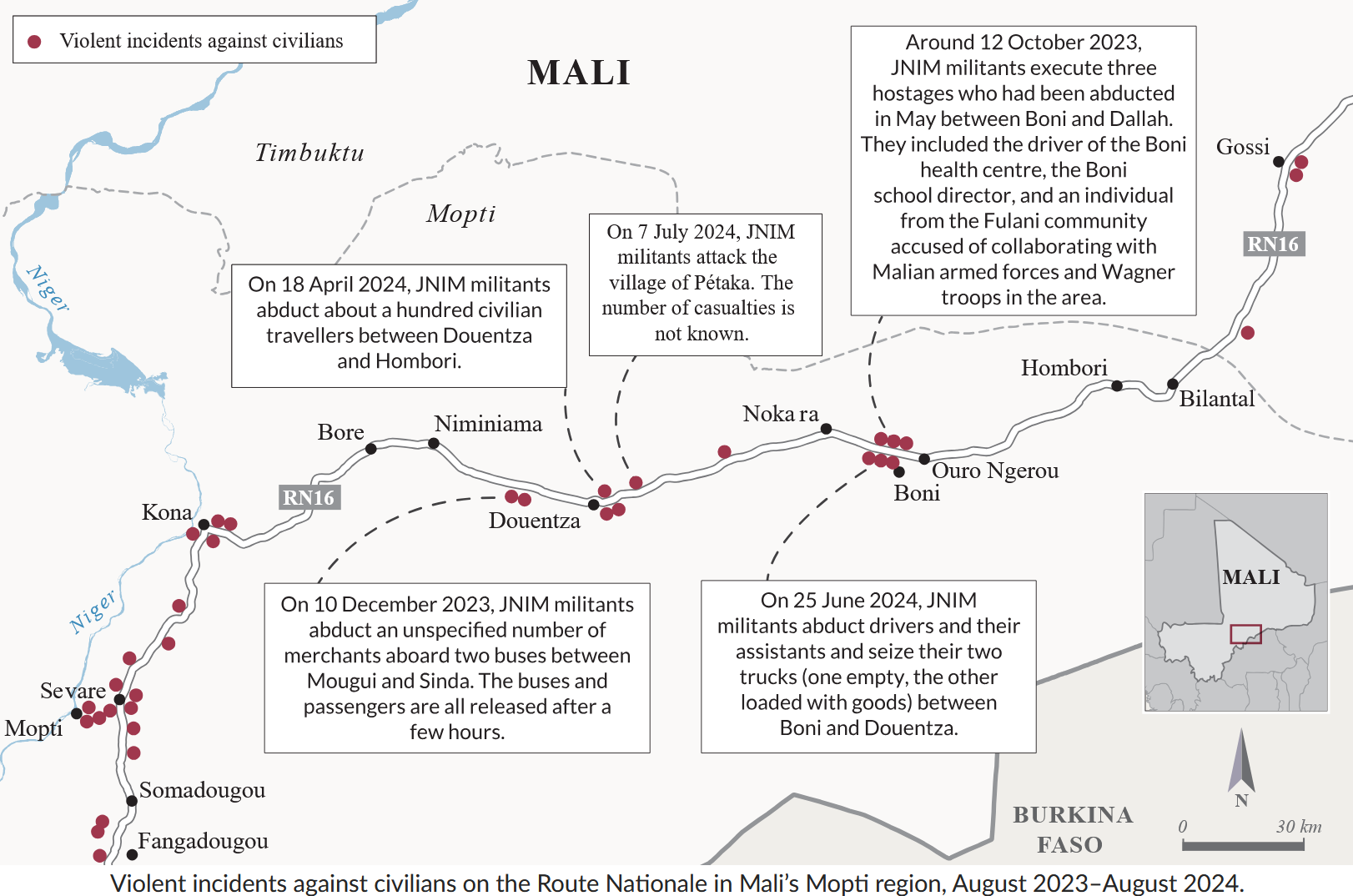

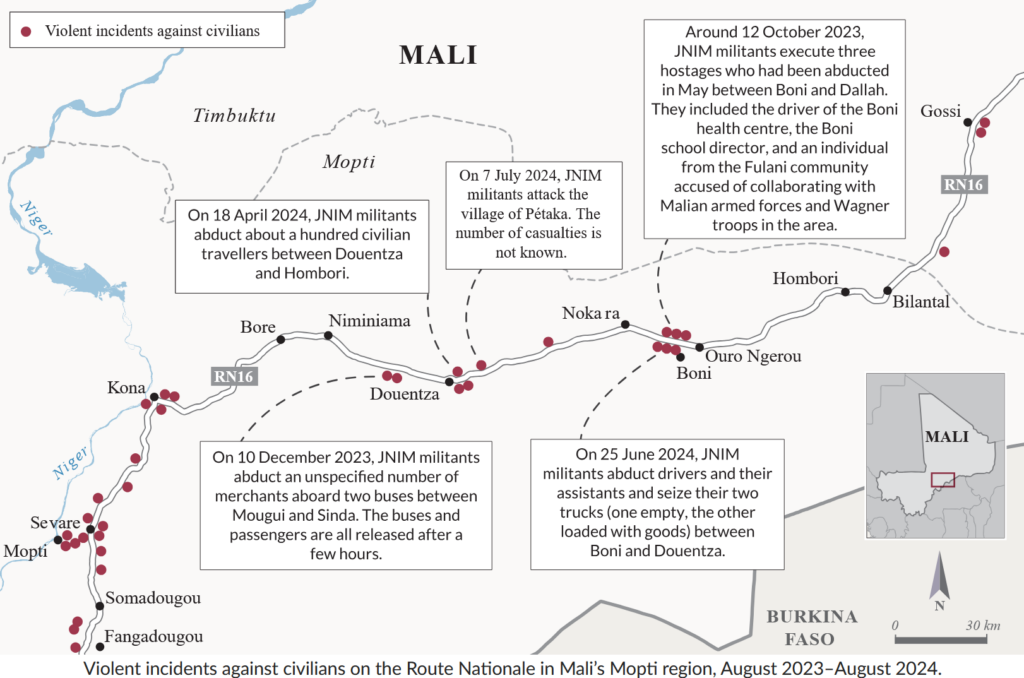

Figure 1 Violent incidents against civilians on the Route Nationale in Mali’s Mopti region, August 2023–August 2024.

Source: Based on ACLED data

JNIM usually seeks to differentiate itself from its local jihadist rival, Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel), through better treatment of civilians. It also typically exerts quite a high degree of control over its fighters, to prevent them from extorting civilians. JNIM’s violence against civilians tends to be targeted and in line with clear political objectives.10 However, these acts of extortion and apparently indiscriminate attacks against road users and truck drivers around Boni should not be read as the wholesale adoption of a more predatory, criminal strategy by JNIM.

Roads as spaces of enhanced civilian targeting

This is not to say that JNIM is not in need of money nor that it is never tempted by criminality. Indeed, JNIM cells in Mopti are reportedly short of money, partly due to increased aerial surveillance over Serma forest, which has restricted their ability to steal livestock from those communities they deem acceptable targets.11 However, the seizure of belongings from the few road users attempting to enter Boni does not constitute a serious revenue generation strategy. Nor is JNIM attempting to resell the trucks it seizes – instead, it burns them, albeit after confiscating the cargo.

The seizing and burning of trucks, and indeed thuggish and indiscriminate violence towards road users, has been perpetrated by JNIM elsewhere. While the aims of the Boni blockade are local, and intended to elicit compliance from the resident population, JNIM does also tend to exhibit a higher degree of violence and unjust behaviour towards people in transit, especially road users passing through areas the group is attempting to control. The violence and pillaging in Boni reflects not only JNIM’s local aims, but also the challenge that roads as mobile spaces present to JNIM – rather than a pivot by JNIM to greater criminality. A similar trend can be seen in JNIM’s history of violence on roads in Burkina Faso.

Traffic on Burkina Faso’s major roads, particularly in the north-east, began to grind to a near-halt in 2022, provoking localized shortages of goods. This was in large part because JNIM frequently attacked passenger transport and trucks. Trucks were stopped by armed men on the road, and the drivers were told to follow fighters’ directions and drive into the bush to a secluded location.12

The goods in the truck would be taken, and typically the truck would be torched or abandoned.13 While the drivers would usually be released, the trauma of the ordeal and the loss of their truck meant that most lost their livelihoods. While the military tried to escort large convoys of trucks to keep goods moving, these convoys became the targets of some of the worst mass attacks. For instance, in September 2022, 11 soldiers and more than 50 civilians were killed after a JNIM ambush on a convoy approaching the blockaded city of Djibo.14

The gains of these attacks on roads for JNIM are twofold. By attacking convoys nominally protected by the state, it sends a clear signal that the state cannot protect civilians, to the point where any association with the state becomes perceived by civilians as a source of danger. The second benefit of substantially limiting movement on roads is that it helps the group to entrench control over territories it already holds.

A defensive form of offensive behaviour

A key goal of JNIM in resorting to violence is to prevent state-linked individuals infiltrating areas it controls. Paranoia around state informants sharing intelligence with security forces is also a key driver of other JNIM behaviour, including its widespread use of kidnapping.15

Violence on roads, for JNIM, is ultimately a defensive strategy that involves offensive violence. However, this form of defensiveness substantially undermines the local popular legitimacy that JNIM has tended to build in the Sahel, which often relies on offering economic incentives. JNIM can often make the case that civilians will be freer to pursue local economic opportunities in peace under their rule. This is particularly effective in places where most economic opportunities have an illicit dimension – such as smuggling, artisanal gold mining or the grazing of cattle in protected areas.

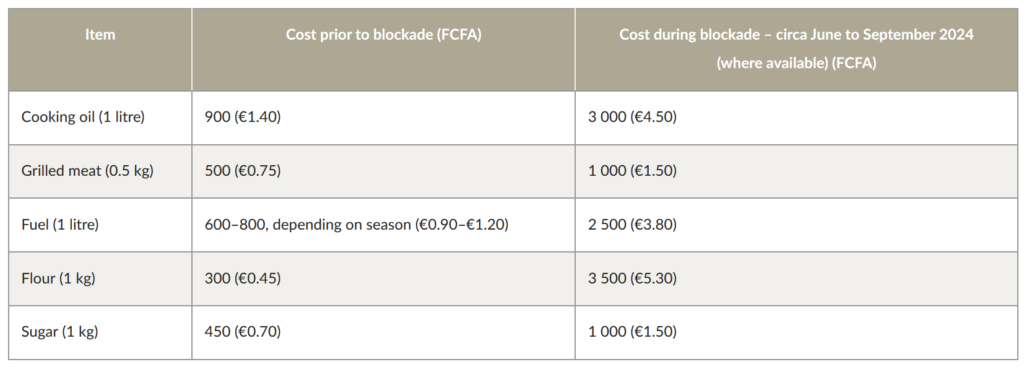

However, in applying the blockade against Boni, JNIM seems unperturbed by the resultant damage to local communities’ livelihoods. It is difficult to overstate the impact on those affected; some goods in Boni are selling for 10 times the pre-blockade price (see Figure 2).16

Still, the town’s residents emphasize that the main problem is extreme scarcity rather than price. Flour, for instance, has not been available since April 2024. Residents are relying on fruit and herbs, alongside stocks of meat, but the humanitarian situation is acute. One resident even reported being prevented from harvesting herbs by JNIM fighters:

On 7 August, I went out of town to look for ‘oulo’, a herb that grows a lot in the area and is eaten in times of severe famine … a unit of three motorbikes from the jihadists came and asked me to leave what I’d already picked …. Their leader told me that they were going to lay siege to Boni until the people of Boni returned to God.17

Figure 2 A comparison of prices for staples in Boni before the blockade and in August 2024.

Source: Telephone interviews with Boni residents, August 2024

Ultimately, JNIM has calculated that the costs of blockading Boni are outweighed by the risks generated by residents colluding with personnel at the newly established army base. Put another way, legitimacy building has been put on hold until such time as the leadership’s perception of risk declines to a level that it judges is commensurate with lifting the blockade. While JNIM is generally more willing to deploy violence against mobile, transient populations, it is also prepared to use extreme coercion against those it hopes eventually to win over; or even those it has previously invested significantly in winning over.

Notably, in West Africa, a person’s physical mobility (i.e. their access to good, reliable transport) is deeply connected to their social mobility, to the point where those with poor transport options are economically disadvantaged from birth.18 In this context, JNIM’s strategy in Boni is conceived as a temporary extreme, designed to relieve intensified military pressure.

Conclusion

JNIM’s ongoing blockade of Boni helps us to understand why armed groups tend to veer towards relatively severe predatory behaviour on roads, even when such behaviour damages the legitimacy they are trying to cultivate over the longer term. In this case, violence and pillaging aim not just to force residents into compliance, but to discourage all possible road movement that could also represent a threat. JNIM’s local legitimacy in Boni will be deeply damaged, but that damage is intended by the group to be temporary. Judging from the experience of Burkina Faso, transient populations on roads are viewed as a more constant threat, and will be at higher risk until the group is absolutely confident of its control.

In conflict-affected areas, danger on roads (and the economic consequences) represents one of the most acute ways that many civilians experience instability. This is certainly not unique to the Sahel, but a consequence of armed group activity around the world, including elsewhere in West Africa.19 Roads, by consequence, are a critical – and opportune – space for positive state interventions. State efforts to secure mobility could have profound economic benefits and counter armed groups’ rhetoric on how the state restricts freedoms – although for such a measure to work, it is critical that state agents do not themselves extort vulnerable citizens on the move.