Key Takeaways:

Niger. JNIM claimed an attack on a border post in northern Niger near the border with Algeria, marking the group’s first attack in far northern Niger. Nigerien Tuareg rebels also gave a competing claim for the attack but failed to provide evidence. The competing claims possibly indicate that the two groups are coordinating their operations, as Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) has done with Tuareg rebels in Mali. JNIM and the Nigerien Tuareg rebels have similar short-term economic and military objectives that involve a common enemy in the Alliance of Sahel States that could encourage cooperation to augment their capacity and capabilities in northern Niger. Both groups have mutual ties with the Malian Tuareg rebels and shared ethnic bonds that could facilitate this link.

DRC. The DRC and Rwanda agreed to move forward in Angolan-mediated peace negotiations, but a lasting agreement remains unlikely in the short term as the parties still disagree on key aspects of the proposed deal. The Rwandan-backed March 23 Movement (M23) rebels also launched a new offensive on the Congolese army (FARDC) and its allied militia groups in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which risks derailing the Luanda Process by ending a ceasefire that has been in place since August. The M23 rebels likely launched the offensive on October 20 to increase pressure on the DRC and influence the Luanda Process negotiations.

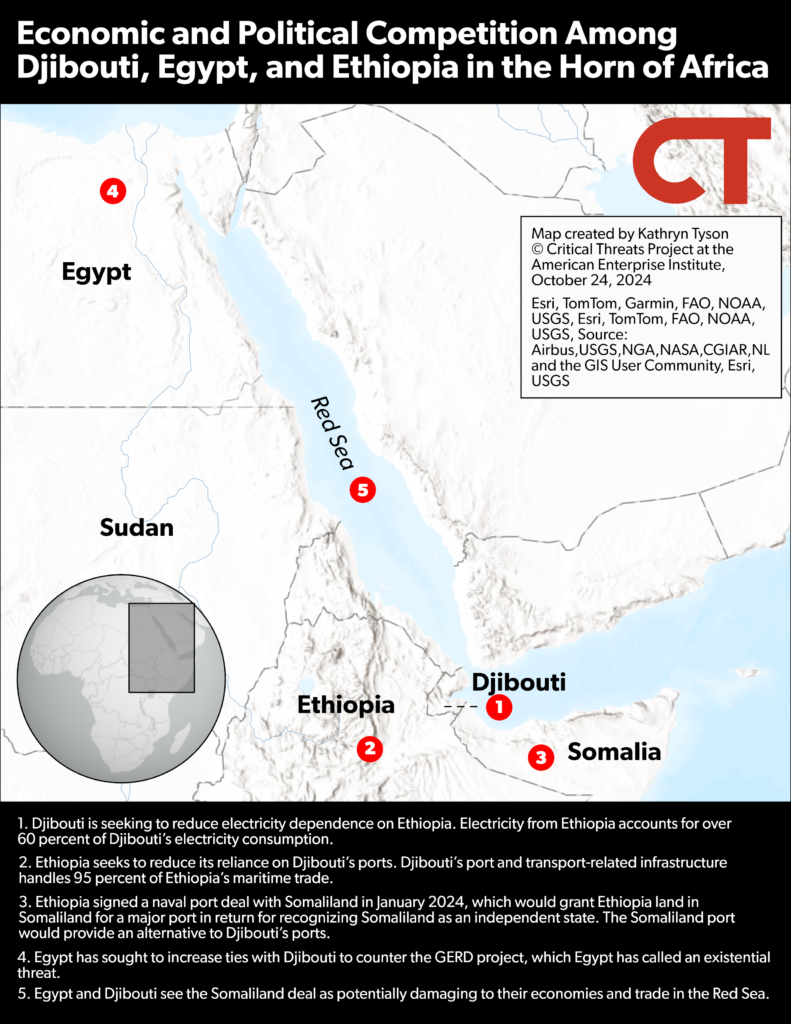

Djibouti. Djibouti and Egypt signed a contract to construct a solar power plant in Djibouti on October 14, representing growing electricity cooperation between Egypt and Djibouti since 2019. The contract is part of a changing balance in the Ethiopia-Djibouti partnership as both countries seek to reduce their reliance on each other. Egypt has also sought to increase ties with Djibouti over the past several years as part of its efforts to counter and isolate Ethiopia.

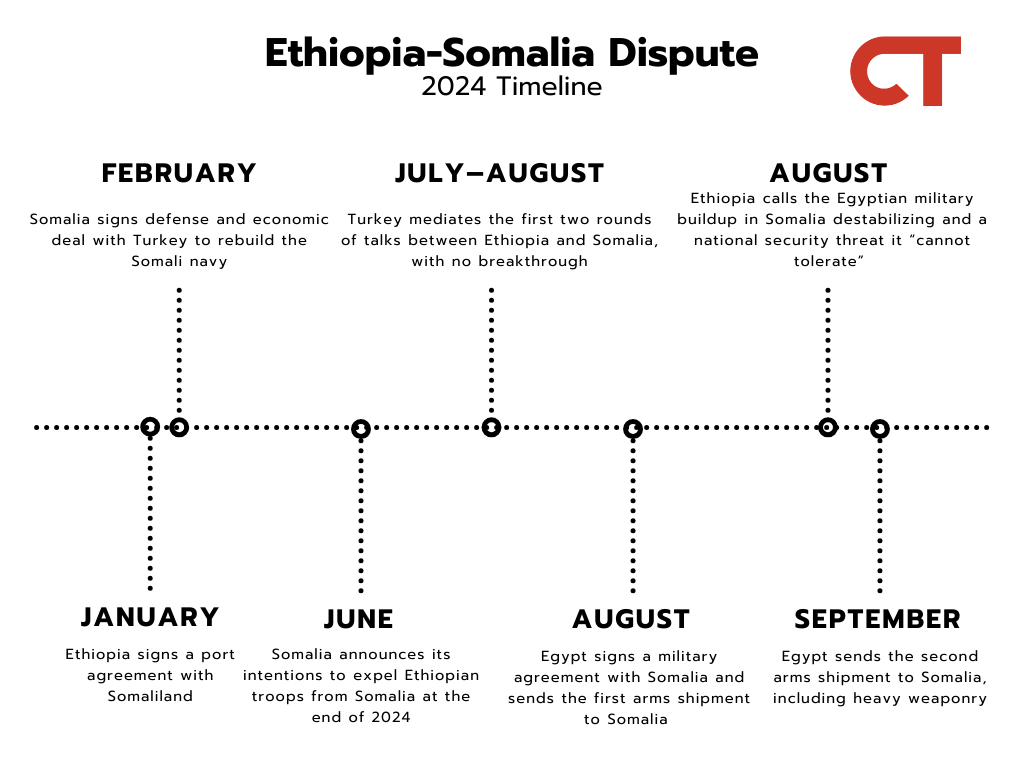

AUSSOM. Somalia and Ethiopia are likely trying to win support for their separate visions on Ethiopia’s involvement in the new AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia. Somalia plans to exclude Ethiopia from the new mission and replace its contingent with Egyptian troops in retaliation for Ethiopia’s port deal with Somaliland, which Somalia has repeatedly called illegal. Regional and international partners disagree on Somalia’s plan to replace Ethiopia with Egypt as the November 15 deadline to submit the mission plans to the UN Security Council approaches.

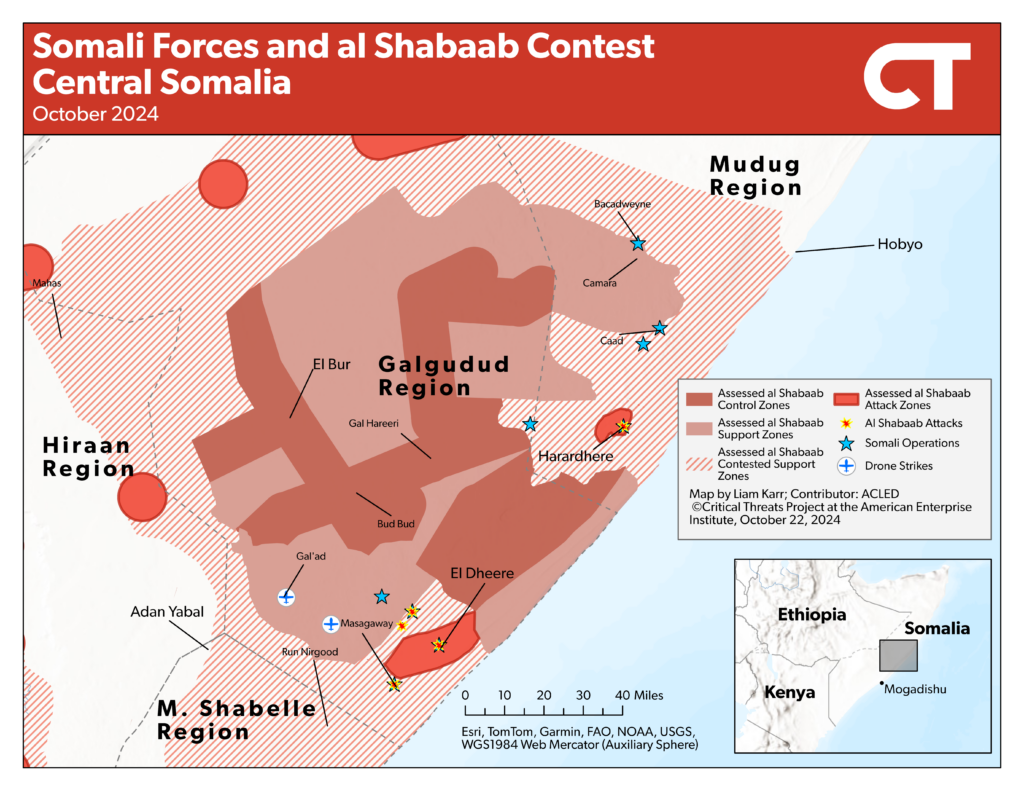

Somalia. The SFG and allied local clan militias have increased operations since October to clear contested areas that serve as a buffer zone and al Shabaab staging ground between key government-held district capitals and al Shabaab’s last remaining stronghold in central Somalia. Somali forces continue to face major political and military challenges to sustaining offensive operations and holding territory.

Assessments:

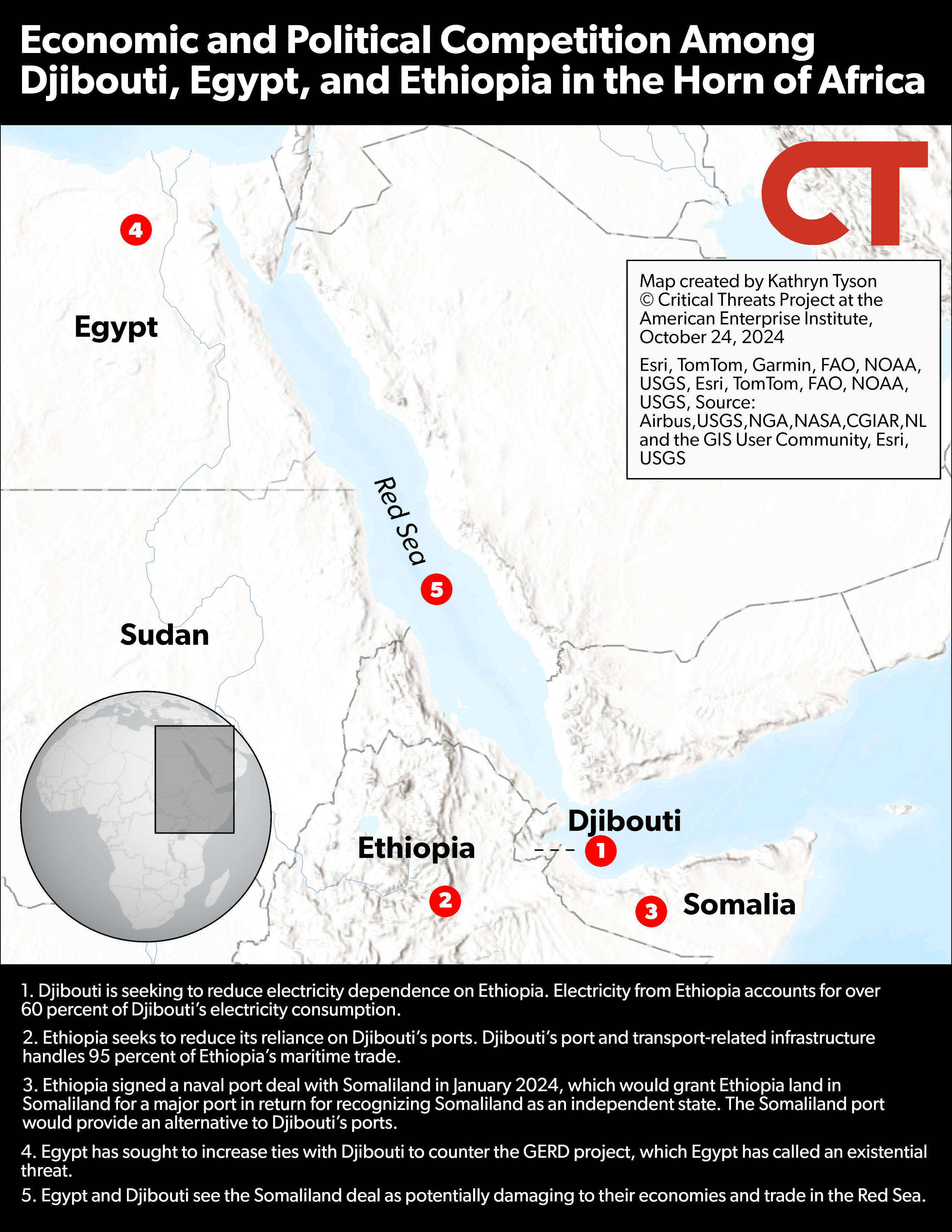

Niger

JNIM and Nigerien Tuareg rebels separately claimed an attack on a border post in northern Niger near the border with Algeria. The attackers targeted a security checkpoint in Assamaka, Niger, less than 10 miles from the Algerian border, on October 19.[1] Assamaka’s military post is comprised of three mixed positions that the National Guard, National Police, and Nigerien Army man.[2] Nigerien officials reported the attackers killed six soldiers and one civilian.[3]

JNIM and Nigerien Tuareg rebels both claimed the attack. The Free Armed Forces (FAL), a Nigerien Tuareg rebel group led by exiled former minister Rhissa Ag Boula, released a statement on October 19 taking credit for the offensive.[4] The FAL is an evolved movement of the Council of Resistance for the Republic (CRR), a group Boula created after the 2023 Nigerien coup to “promote an armed front against the junta.”[5] The group is allied with other Nigerien rebel groups, including the primarily Toubou Patriotic Liberation Front (FPL), which disabled a part of Niger’s China-funded oil pipeline in June 2024.[6] Boula is currently exiled in France after last year’s coup.[7] JNIM claimed responsibility for the attack shortly after and released pictures of looted materials.[8]

This is the first time JNIM has claimed an attack in far northern Niger. Unidentified militants presumed to be bandits sporadically attack civilians and soldiers in Assamaka and surrounding areas, but JNIM has never claimed involvement in any of these attacks. The closest JNIM attack to the Algerian border in Niger was over 150 miles south, near Midal in the Tahoua region, in July 2017, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) project.[9] The October 19 assailants retreated to Mali after the attack, where JNIM has rear support zones.[10] This movement and JNIM’s photo evidence support its claim that it was behind the attack. Unknown militants were involved in another clash with the Nigerien army near Assamaka on July 30 and retreated toward Mali after the firefight.[11] The army arrested three militants and seized two vehicles but made no connections to JNIM.

Figure 1. JNIM Contests Sahelian Forces Along the Algerian Border

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

The competing claims possibly indicate that the two groups are coordinating their operations, as JNIM has done with Tuareg rebels in Mali. JNIM and the Tuareg rebel coalition in Mali each provided a contested claim for an ambush on a security-force convoy that killed at least 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers near the Algerian border in Mali in July.[12] AP, CTP, and Radio Free Liberty/Radio Europe all assessed in that case that the fighters involved in the ambush had ties to both JNIM and the Malian Tuareg rebel coalition.[13] AP and Radio Free Liberty/Radio Europe specifically reported that the Malian Tuareg rebels repelled the convoy’s advance, which led it to retreat into a JNIM ambush. CTP has no direct evidence that JNIM is cooperating with the Nigerien Tuareg rebels, however, and cannot confirm to what degree any cooperation would entail.

JNIM and the FAL have mutual links with the Tuareg rebels in Mali, a common enemy in the Alliance of Sahel States, and shared ethnic ties that could help encourage and facilitate cooperation to augment their capacity and capabilities in northern Niger. CTP has previously noted that the JNIM subgroup in northern Mali has significant historical and shared ethnic ties with the Malian Tuareg rebels.[14] CTP also assessed that JNIM is almost certainly deconflicting activity and may even be coordinating some attacks with the Malian Tuareg rebel coalition.[15] Boula has historical connections to the Tuareg networks across the Sahel and maintained contact with the Malian Tuareg rebels.[16] Boula has also sought to tighten this relationship in the wake of the Niger coup and the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States. French media has reported that Boula aims to “coordinate the efforts of the different groups and open multiple fronts against the Malian and Nigerien armies united in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES).”[17] CTP previously noted that JNIM’s ties with Malian Tuareg groups also provide it an opportunity to build its relationships with the transnational Tuareg population and embed itself in regional smuggling networks.[18]

Both groups have economic and military interests in degrading the government’s influence along the Algerian border. JNIM and the Nigerien Tuareg rebels are likely seeking to degrade the Nigerien government’s ability to influence the trafficking networks that run through Assamaka. The Assamaka border crossing is the main crossing point between Niger and Algeria, making it one of the major migratory routes from sub-Saharan Africa to northern countries. The Nigerien junta lifted migration restrictions in December 2023, and soldiers are embedded in the local migrant smuggling economy.[19] JNIM and FAL already influence or control many other segments of this trans-Saharan network in northern Mali and Niger.[20]

The attack also supports preexisting separate JNIM and FAL military campaigns. The broader Nigerien rebel coalition that includes the FAL has explicitly tried to undermine the junta by attacking other economically vital targets, including oil pipelines.[21] JNIM, alternatively, could use rear support zones along the Algerian border in Niger to help protect its long-established support zones along the Malian-Algerian border. Malian and Russian forces sent a reinforced convoy to reattempt to capture Tinzaouten in early October; however, the convoy withdrew without reaching the area.[22] Stronger havens in Niger would create a rear support zone that JNIM could use as a fallback point or staging ground if it faces increased pressure from Malian and Russian forces. Degraded government control over the area would also degrade the Nigerien government’s ability to assist its Malian and Russian allies in any offensive on the Algerian border.

DRC

The DRC and Rwanda agreed to move forward in Angolan-mediated peace negotiations, but a lasting agreement remains unlikely in the short term as the parties still disagree on key aspects of the proposed deal. Foreign ministers from Angola, the DRC, and Rwanda met in Luanda, Angola, on October 12 under the auspices of the Luanda Process, a trilateral peace initiative mediated by Angola.[23] The parties signed off on a “harmonized plan” for the FARDC to launch an offensive against the Hutu armed group Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) and for Rwanda to initiate the “disengagement of forces” and the “lifting of defensive measures” in the eastern DRC.[24] Rwanda’s Tutsi-dominated government views the FDLR as a threat due to the DRC’s use of the FDLR as an anti-Rwandan proxy, the FDLR’s ties to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and the group’s anti-Tutsi ideology. Officials from all sides agreed to jointly draft a conceptual strategy before the next ministerial meeting on October 30 on how to launch the anti-FDLR offensive.[25]

The Congolese foreign minister declined to sign a similar version of the plan during the last round of meetings on September 14, halting a potential breakthrough.[26] The Congolese foreign minister accused Rwanda of providing insufficient details about the Rwanda Defence Force’s (RDF) disengagement and argued its withdrawal should occur simultaneously with FARDC’s offensive on the FDLR.[27] The Rwandan foreign minister responded by denouncing Kinshasa for negotiating in bad faith and purposefully sabotaging the talks.[28]

Officials from the DRC and Rwanda remain divided over core details of the plan’s measures. The Congolese prime minister and French media claimed after the October 12 discussions that Rwanda agreed to withdraw its estimated 4,000 troops from the eastern DRC in exchange for the DRC’s parallel commitment to dismantle the FDLR.[29] The UN and US say the Rwandan troops are supporting the Rwandaphone M23 rebels.[30] The Rwandan foreign minister called the claims about the agreement details “baseless” and asserted that Rwanda has never “agreed to present a withdrawal plan for more than 4,000 military personnel,” including during the October 12 meetings.[31] Angolan President João Lourenço held separate telephone conversations on October 19 with the DRC and Rwandan presidents to contain the fallout following the allegations.[32]

Both sides also still do not agree on the sequence and criteria for success that would dictate the implementation of the deal. The official report from the October 12 meeting recorded that the Rwandan foreign minister reiterated support for the original plan formulated in late August by Congolese and Rwandan intelligence officials—stipulating the RDF would begin scaling back its defensive posture five days after FARDC “neutralized” the FDLR—while the DRC restated its demand for concomitant implementation.[33] French magazine Jeune Afrique reported that Rwanda will not fulfill its obligations to “lift defensive measures” until Kigali judges that the action against the FDLR has reached a “satisfactory” level.[34]

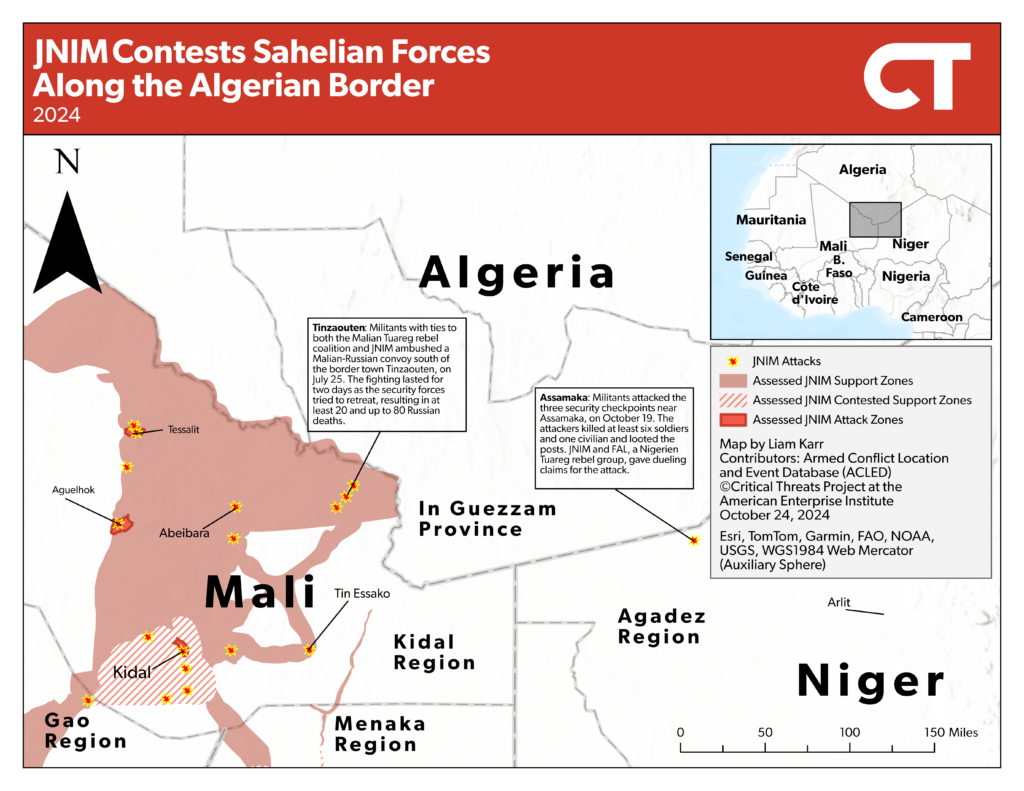

The Rwandan-backed M23 rebels also launched a new offensive on FARDC and its allied militia groups in the eastern DRC, which risks derailing the Luanda Process by ending a ceasefire that has been in place since August. M23 militants attacked pro-Kinshasa militia positions in an area straddling the Rutshuru, Masisi, and Walikale territories of North Kivu on October 20, seizing control of two localities rich in minerals and regarded as strategic access points to the interior of the region.[35] Local residents reported intense fighting, including the use of heavy weaponry, between the M23 rebels and FARDC-aligned militia groups known as “Wazalendo” near the Kalembe and Ihula localities.[36] French media reported that the M23 rebels launched the attack after the rebels claimed the Wazalendo provoked them.[37]

Pro-government forces launched a counterattack but have not retaken the contested areas. Wazalendo militants mounted a counteroffensive on the same day to reoccupy Kalembe, but local media said they failed to reestablish control.[38] The FARDC flew in an unspecified number of troops on helicopters the next day on October 21 and intervened to launch a second counteroffensive with the objective of retaking the town.[39] Local sources reported Wazalendo militants succeeded in reoccupying Kalembe, but both FARDC and the M23 rebels claimed they retained control of the locality.[40]

Figure 2. Clashes Continue in Eastern DRC After the August 4, 2024, DRC-Rwanda Ceasefire

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

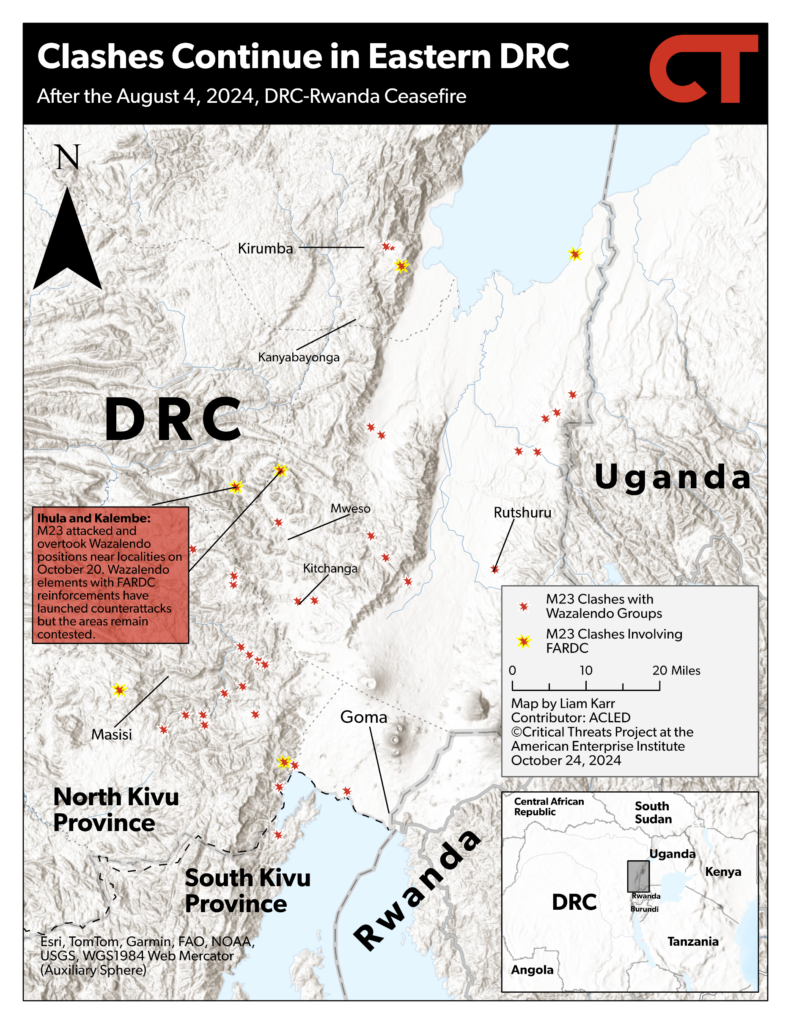

The renewed M23 offensive violates a fragile ceasefire, which has been key to advancing the ongoing peace talks in Luanda. DRC and Rwandan officials met in late July as part of the Luanda Process and agreed to a cessation of hostilities that went into effect on August 4.[41] The ceasefire halted M23 advances that had been ongoing since June 2024 within the Rutshuru and Masisi territories, which increased the group’s territorial control in the eastern DRC by 21 percent.[42] The UN claims Rwanda’s military interventions in the eastern DRC have been decisive to the rebel group’s “superior combat strength” since its resurgence in 2021 through Rwanda’s provision of troops, training, and military equipment.[43] During the last Luanda meeting on October 12, officials from the DRC and Rwanda reaffirmed their commitment to abide by the ceasefire and agreed to submit the names of officers who will represent their respective countries and help establish a regional mechanism to enforce the agreement’s terms.[44] The Angolan government accused the M23 of violating the ceasefire with its new offensive and called on all parties to observe its implementation.[45]

Figure 3. The Ceasefire Has Decreased Fighting Between M23 and FARDC in the Eastern DRC

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

However, the M23 claims that it is not subject to the ceasefire and that it is only defending itself from FARDC attacks.[46] The M23 believes the Luanda discussions are “incomplete” without its participation and has repeatedly demanded direct negotiations with the Congolese government since its resurgence in 2021.[47] The Rwandan foreign minister denied reporting from France-based investigative outlet Africa Intelligence after the September 14 disagreement that the “harmonized plan” formulated in late August—and agreed on in principle on October 12—included the withdrawal of the M23 from Congolese soil.[48]

The Congolese government has labeled the M23 as “terrorists” and refuses to negotiate directly with the group.[49] Angolan officials recently proposed direct dialogue between Kinshasa and M23 representatives, but the Congolese government declined.[50] Kinshasa restated its position after the recent M23 offensive that “no negotiations are possible outside the framework set by the Luanda Process.”[51] The DRC has also excluded the M23 rebels from talks under the East African Community initiative known as the Nairobi Process, which aimed to facilitate interstate dialogue between the DRC government and rebel groups in the eastern DRC.[52]

The M23 rebels likely launched the offensive on October 20 to increase pressure on the DRC amid the Luanda Process negotiations. French media reported that the main military objective of the M23’s offensive is to “absorb” pro-government militias and “continue their advance in the region.”[53] An elected official from the Walikale territory expressed concern that the DRC government is “distracted by the Luanda ceasefire” and that Wazalendo fighters “could either ally themselves with the enemy to preserve their lands, or turn against a government that would become suspect by allowing the aggressors to occupy their villages.”[54]

The timing of the M23’s attack coincides with the next round of Luanda negotiations, suggesting it aims to affect the discussions despite its formal absence. The M23 fighters were stationed only 10 kilometers from the town for roughly eight months before launching the offensive, which indicates that external factors contributed to the M23’s sudden shift in operational strategy, leading it to attack the two strategic localities.[55] A resident from Walikale told Reuters that local sentiment reflects the belief that the M23 rebels “want to turn up the heat in anticipation of the upcoming exchanges” under the Luanda Process.[56]

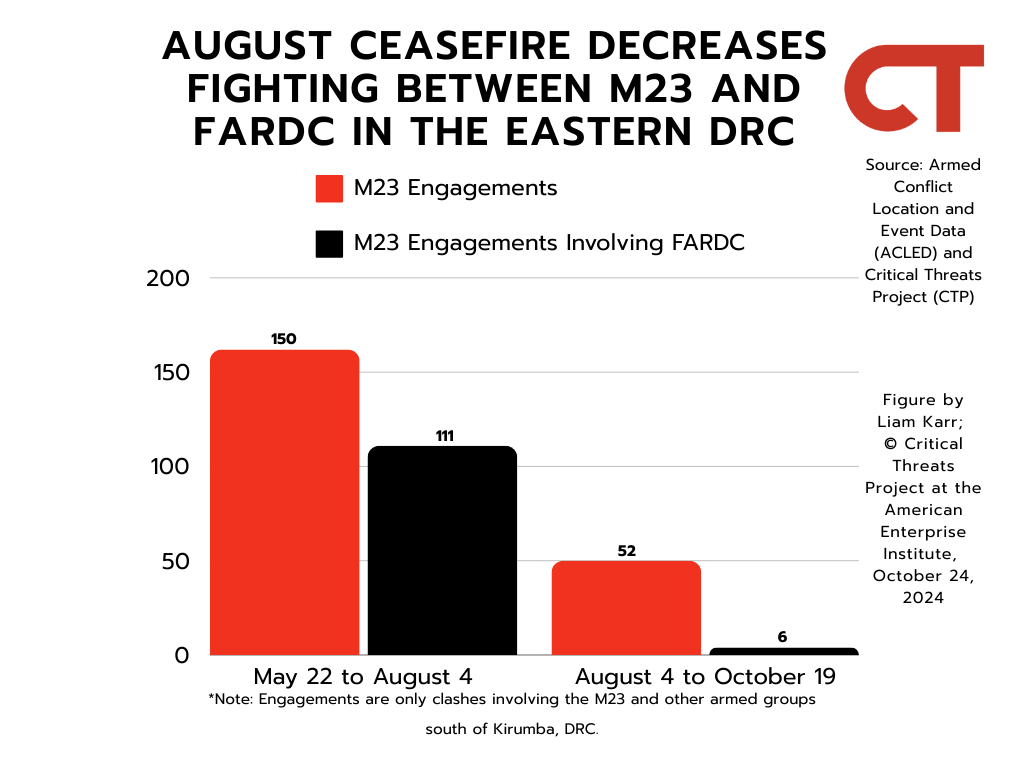

Djibouti

Egypt and Djibouti signed a contract to construct a solar power plant in Djibouti on October 14, representing growing electricity cooperation between Egypt and Djibouti since 2019.[57] Egypt will finance and build a 276.5-kilowatt solar power plant, according to the agreement.[58] Egyptian Minister of Electricity and Renewable Energy Mahmoud Esmat highlighted the “strong ties” between Egypt and Djibouti and expressed Egypt’s interest in further strengthening cooperation in renewable energy with Djibouti. Djibouti’s Minister of Energy and Natural Resources Yonis Ali Guedi said the agreement represents Egypt and Djibouti’s “strong and growing relationship.” The contract demonstrates ongoing coordination between Egypt and Djibouti on electricity since the countries signed a memorandum of understanding to enhance electricity cooperation in 2019.[59] This cooperation is also part of an ongoing effort by Djibouti to develop more sources of renewable energy since 2014, when it announced a plan to achieve energy independence using 100 percent renewables by 2035.[60]

The contract is part of a changing balance in the Ethiopia-Djibouti partnership as both countries seek to reduce their reliance on each other. Djibouti has sought to reduce electricity dependence on Ethiopia. Electricity from Ethiopia accounts for between 60 and 80 percent of Djibouti’s electricity consumption and generates significant foreign exchange for Ethiopia.[61] The solar energy contract represents less than 1 percent of Djibouti’s total daily energy consumption, but Djibouti has taken other steps to increase its domestic power production.[62]

Ethiopia seeks to reduce dependence on Djibouti’s ports.[63] Djibouti’s port and transport-related infrastructure handles 95 percent of Ethiopia’s maritime trade.[64] Ethiopia signed a naval port deal with Somaliland in January 2024, which would grant Ethiopia land in Somaliland for a major port in return for recognizing Somaliland as an independent state.[65] The Somaliland port would provide an alternative to Djibouti’s ports, giving Ethiopia access to Red Sea shipping lanes via the Bab al Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen, which connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.[66] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has described Red Sea access as an existential issue and “natural right” that Ethiopia would fight for if it could not secure it through peaceful means.[67]

Djibouti would suffer economically if the Somaliland port deal goes through. Port revenues, along with foreign military bases, are Djibouti’s primary source of income.[68] Djibouti would lose the almost $1.5 billion in annual fees it charges Ethiopia for the ports and see commercial transit plummet.[69] Djibouti offered Ethiopia a new port in northern Djibouti in July 2024 as an alternative.[70]

Egypt has also sought to increase ties with Djibouti over the past several years as part of its efforts to counter and isolate Ethiopia. Egypt is attempting to secure regional alliances to counter the Ethiopian Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD).[71] Egypt has repeatedly labeled the GERD an existential threat that will degrade—or enable Ethiopia to control—its Nile water supply.[72] Egypt President Abdel Fattah al Sisi made the first visit to Djibouti in 2021 in over three decades to strengthen bilateral ties with Djibouti in the context of the GERD.[73]

Djibouti and Egypt agreed that the GERD should be implemented based on a “binding legal agreement” on the projects’ management, a line that Egypt has pushed for several years.[74] Sisi reiterated Egypt’s position on the GERD to Djibouti’s president in 2022.[75] Egypt views Ethiopia’s deal with Somaliland as a potential threat to its own Red Sea rents, which amounted to $9 billion annually from Suez Canal receipts before the Israel-Hamas war and the Yemen-based Houthi attack campaign on Red Sea shipping.[76]

Egypt’s growing relationship with Eritrea could be a limiting factor in its partnership with Djibouti due to the uneasy relationship between Djibouti and Eritrea. Egypt has also used the port deal to bolster relations with other concerned regional actors, such as Eritrea and Somalia, to further isolate Ethiopia. The three countries formalized a de facto anti-Ethiopian alliance following a trilateral summit in Eritrea on October 10.[77] Eritrea also seeks to counter Ethiopia due to a fallout in relations related to the 2022 Tigray war and Abiy’s strong rhetoric on Ethiopian Red Sea access that Eritrea viewed as a threat to its Red Sea coastline.[78]. The Djiboutian president recently expressed concern over the growing Eritrean-Egyptian cooperation in a meeting with the Somali president, according to unspecified Djiboutian officials on October 23.[79] Djibouti and Eritrea had a decade-long territorial dispute over the Ras Doumeira border area and Doumeira island in the Bab el Mandeb strait that resulted in a brief military conflict in 2008 that killed at least 100 soldiers.[80] The two counties avoided another round of fighting in 2017 and restored diplomatic relations in 2018, but the dispute remains unsolved despite UN and AU mediation efforts.[81]

Figure 4. Economic and Political Competition Among Djibouti, Egypt, and Ethiopia in the Horn of Africa

Source: Kathryn Tyson.

AUSSOM

Somalia and Ethiopia are likely trying to win support for their separate visions on Ethiopia’s involvement in the new AU peacekeeping mission in Somalia. The UN approved a new African Union (AU) peacekeeping mission in Somalia in August 2024 to replace the current mission, the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) starting in 2025.[82] Somalia and Ethiopia have conducted separate meetings with AU troop-contributing countries to discuss the transition from ATMIS to the new AU Support and Stabilization Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM). Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud met with presidents from Burundi, Djibouti, Kenya, and Uganda to discuss the ATMIS transition and enhancing security cooperation against al Shabaab during a tour of the region between October 19 and 22.[83] Ethiopian President Ahmed held a meeting with defense ministers from AU troop-contributing countries on October 16 to discuss the transition.[84]

Somalia plans to exclude Ethiopia from the new mission and replace its contingent with Egyptian troops in retaliation for Ethiopia’s port deal with Somaliland, which Somalia has repeatedly called illegal.[85] Somalia and Egypt have signed several agreements since August 2024 that aim to enable Somalia to replace the 8,000–10,000 Ethiopian troops fighting al Shabaab in Somalia.[86] Somalia is both doubling down on its plan to expel Ethiopian forces and insisting that it has the final say in who participates in ATMIS. Somalia’s Foreign Ministry reiterated on October 23 that it would not allow Ethiopian forces to participate in ATMIS.[87] The foreign ministry added that Somalia has a right to determine which troop-contributing partners joins the missions and that “all decisions must prioritize our national interests.”[88] Ethiopian officials have implied that Ethiopian troops will stay in Somalia past 2024 if Ethiopia has international and local support, regardless of whether Somalia approves their presence.[89] Ethiopia seeks to maintain a buffer zone against al Shabaab in Somalia and prevent an al Shabaab offensive into Ethiopia, as the group launched in 2022.[90]

Figure 5. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

Regional and international partners disagree on Somalia’s plan to replace Ethiopia with Egypt as the November 15 deadline to submit the mission plans to the UN Security Council approaches. Regional troop-contributing countries have criticized Egypt’s potential participation in the mission. Some international and regional partners warned that Egypt’s inclusion would give Egypt a victory in its rivalry with Ethiopia and undermine the main objective of the mission to counter al Shabaab.[91] Uganda’s foreign minister also argued that Egypt’s inclusion in the mission would disrupt the mission’s structure, given that the current troop-contributing countries have been working together in Somalia for a decade.[92] The US has also expressed tacit support for the presence of Ethiopian troops in Somalia. The US assistant secretary of state for African affairs said in September 2024 that “all of Somalia’s neighbors—Djibouti, Kenya, and Ethiopia—as well as important contributions by Uganda and Burundi have been important over the years as they’ve worked collectively together shoulder to shoulder to help the Somali people.”[93]

However, the AU already provisionally accepted Egypt’s offer to participate in the new mission in August.[94] Egypt, Eritrea, and Somalia released a joint statement supporting the deployment of Egyptian peacekeeping forces during a summit on October 10.[95] The AU, UN, and Somalia held private talks in early October over the mission design, but there were no publicly announced breakthroughs in the disagreement over the Egyptian troops.[96]

Somalia

The SFG and allied local clan militias have increased operations since October to clear contested areas that serve as a buffer zone and al Shabaab staging ground between key government-held district capitals and al Shabaab’s last remaining stronghold in central Somalia. Somali forces have conducted at least 12 operations to clear al Shabaab from rural areas of the Galgudud region, north of El Dheere town, since October 3.[97] Somali forces also began offensive operations roughly 75 miles northeast to clear al Shabaab positions near Harardhere town in the Mudug region. Somali forces have conducted at least five operations around Harardhere since October 14, including bloodlessly securing three villages after al Shabaab militants retreated from the area.[98] Al Shabaab has also increased its attacks in both areas in October as it targets patrolling Somali forces.[99] These operations are the first time that Somali forces have sustained operations around El Dheere since July 2024 and around Harardhere since the first quarter of 2024.[100] The October offensive is also more heavily focused in the Galgudud and Mudug regions, whereas Somali forces have focused on clearing areas of the eastern Middle Shabelle region throughout 2024.

Figure 6. Somali Forces and al Shabaab Contest Central Somalia, October 2024

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project.

Somali forces are targeting areas that al Shabaab recaptured in 2023 and 2024 and has since used support attacks on government-held areas. Al Shabaab retook the areas in El Dheere district after thwarting the last major Somali Federal Government (SFG) offensive to capture the last al Shabaab–controlled district capital, El Bur. Somali forces reached the town but were overextended, leaving a string of weakly defended forward operating bases in the rural areas they cleared to reach the town.[101] Al Shabaab regrouped and overran one of these bases, inflicting significant casualties and causing the SFG’s position to disintegrate, isolating El Bur and forcing Somali forces to withdraw from it and several other rural villages.[102] Al Shabaab retook several rural areas north of Harardhere after local militias withdrew in March 2024 due to disputed salary payments.[103] Al Shabaab has since used these rural areas to isolate the SFG-controlled district capitals and stage large-scale attacks on SFG bases throughout the area.[104]

Somali forces continue to face major political and military challenges to sustaining the offensive and holding territory. Local reports have alleged that some local militias have left the anti–al Shabaab coalition in recent months after not receiving promised salary payments. Somalia media reported in October that there was discontent among the local Abgaal subclan militia around El Dheere after the government failed to honor bounty promises for killing al Shabaab militants.[105] Another group of subclan militias withdrew from their defensive positions in Harardhere town in September after they alleged that they had not received any payment since the offensive began in 2022.[106] Al Shabaab played on similar tensions to peel local support away from the government throughout 2023 and 2024.[107] Unified clan support was crucial to the SFG’s initial success in 2023.[108]

SFG officials are also preoccupied with the ongoing dispute with Ethiopia and internal political tensions, limiting their bandwidth to rally local support as they have during previous offensives. Somali President Mohamud worked out of the Galgudud regional capital between September and October 2023 as he rallied local support and helped hold together the militia coalition when the SFG last attempted to capture El Bur.[109] However, Mohamud gave priority to meeting with international allies to rally support against Ethiopia’s port deal with Somaliland in early 2024, leading him to only spend one day in central Somalia during the last multifront offensive.[110]

Mohamud has continued prioritizing regional and domestic political challenges over the latest offensive. He traveled to Burundi, Djibouti, Kenya, and Uganda to discuss the ATMIS transition between October 19 and 22, attended a summit with Egypt and Eritrea in Eritrea earlier in the month, and has not visited central Somalia since the latest uptick in operations began.[111] The Wall Street Journal reported in October that multiple Western officials were concerned that the SFG’s preoccupation with the Ethiopia dispute created an opportunity for al Shabaab to regain momentum.[112] President Mohamud is also expending his domestic political capital trying to reach deals with Somali leaders in southern Somalia on unified one-person, one-vote elections and replacing Ethiopian partner forces with Egyptian soldiers.[113]

Al Shabaab also still likely retains vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) capabilities in central Somalia, which have enabled the group to derail previous offensives. The group has continually withdrawn from key towns to avoid conventional engagements with Somali forces before launching large attacks involving suicide VBIEDs targeting the makeshift Somali bases, often overrunning them, inflicting severe casualties, and forcing Somali forces to withdraw.[114] Al Shabaab has used these attacks to stymie multiple SFG offensives to clear the group’s remaining havens in central Somalia in January, April, and August 2023.[115] Somali forces and international partners are specifically targeting the staging areas that al Shabaab has used to orchestrate these attacks, which is critical to degrading this capability by cutting al Shabaab resupply lines and rear support zones.[116]