This story documents live testimonies about Iranian penetration into Sudan, conveyed by “Al-Hajj,” “Al-Liwaa,” “Al-Diplomat,” and other sources whose names we have withheld for their protection and safety, who all agreed that this penetration into their country poses a threat to regional security in the Middle East and Africa in a way that cannot be ignored.

In the midst of the war in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, you can see the fear in people’s eyes and the awe in their carefully chosen words when dealing with strangers. I thought about this as I waited in the lobby of a hotel near the Blue Nile River for the car that would take me to a meeting at the home of the one person I could trust to provide me with solid details about Iran’s security and military involvement in Sudan. I will refer to him as “Hajj.”

As I waited, I checked my notes. Everything about Sudan was eye-catching: the low standard of living, the appalling poverty rates, the stagnant business environment, the high unemployment rate, the alarming lack of public security. The country was visibly militarized everywhere, even in the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. I could see it from my hotel window, surrounded by the grandeur of the King Farouk Mosque, the Coptic Orthodox Church, and the National Museum of Sudan. It made me wonder: How had this country been snatched from its former state of peaceful coexistence among its neighbors?

Over the past ten years, as a Middle East scholar, I have closely followed Iran’s incursions into Africa and its successful efforts to establish ties with the military establishments of targeted countries. I have observed how Iran has expanded its influence in the region and across the world by creating networks of “non-state actors” and armed militias that sow chaos and ensure the failure of vital national projects under the banner of “resistance and defiance.”

Iran has carefully planned its long-term strategy of “exporting the revolution” on the political, military, economic, and security levels. This strategy began with the Iran-Iraq war and has expanded through Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, all the way to the conflicts in Gaza and Africa. The establishment of security, intelligence, and military infrastructure wherever its tools can reach to build and expand an Islamic Republic is now bearing fruit, despite being seen as poisonous by the West, the East, and many of its neighbors.

After hours of waiting, I finally received a call that a car was waiting for me outside the hotel. It was driven by an armed man in military uniform, and I was accompanied in the car by armed guards. As we drove to the Hajj’s house, my companion stressed the importance of maintaining his privacy and security. After more than 40 minutes of driving through military checkpoints, we arrived at a heavily guarded villa. The Hajj welcomed me with the usual Sudanese hospitality, and joked with me, “Have you adapted to the heat and the sound of gunfire?”

We moved to a secluded corner of the villa’s backyard, away from the house. Al-Hajj dismissed all the guards. After once again stressing the importance of not mentioning his name or any details that might reveal his identity, we began our conversation about the Sudan-Iran issue. Or rather, Al-Hajj began dissecting the relations between the two countries while I listened.

Al-Hajj began by saying that Sudanese-Iranian relations were strengthened by the military coup that brought the Islamic Front to power in Sudan in 1989, a period he witnessed up close. The two countries were ideologically aligned, particularly in their shared hostility toward the United States. Iran supported the military coup and Omar al-Bashir as Sudan’s new president, and provided military and humanitarian assistance throughout the 1990s. Sudan, in contrast, supported Iran’s nuclear ambitions and voted against UN resolutions condemning Iran, particularly on human rights.

Regarding the security and intelligence relationship between Iran and Sudan, Al-Haj explained that it began in the early 1990s under the leadership of Major General Dr. Mahdi Ibrahim, the founder of the Sudanese security system along with Dr. Nafie Ali Nafie. At that time, Sudan’s security apparatus was divided into an internal security agency known as the National Security Service, and an external security agency overseen by the Sudanese Intelligence Service. However, in 2004, Bashir issued a decree merging all security agencies under a unified body called the General Intelligence Service.

Mahdi Ibrahim is credited with being the architect of the security relations between Sudan and Iran. Iran played a major role in shaping the Sudanese security and intelligence system, which was modeled after its own structure in terms of administrative organization, training, and operations. In the early stages, all Sudanese officers and soldiers were sent to Iran for training. Likewise, Iran sent its officers to Sudan to serve as experts and advisors within the nascent Sudanese intelligence apparatus.

During this period, Iran supplied weapons to the Sudanese military and smuggled weapons to affiliated factions throughout the Middle East and Africa. Sudan also became a training ground for extremists from around the world under Iranian influence. Eventually, Iran established weapons manufacturing factories on Sudanese soil.

To enhance its influence over Sudanese society and religious life, Iran established Husayniyyas (Shiite mosques) in Sudan, which served as a gateway to spreading Shiite Islam locally and across Africa. All of this was done under the umbrella of the Iranian Cultural Center, which established 45 branches and schools, such as the Furqan schools that are still operating to this day.

There are no accurate statistics on the actual percentage and number of Shia Muslims in Sudanese society, but various studies indicate that they constitute about 1% of the population, although this number may change. According to a 2009 study by the Pew Research Center , the Shia population in Sudan exceeds 1%, while the 2020 updates to the World Religions Database indicate that Shia represent about 0.07% of the population. According to the 2022 Religious Freedom Report issued by the US Department of State, this small Shia community resides mainly in the capital, Khartoum.

However, official relations between the two countries ended on January 4, 2016, when Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour confirmed to Al Jazeera that Sudan had severed diplomatic relations with Iran due to its sectarian interference in the region and its attacks on the Saudi embassy and consulate in Tehran.

Al-Hajj believes that the severing of diplomatic relations between Khartoum and Tehran in 2016 did not weaken Iranian influence in Sudan at the security, military, and economic levels. This view is consistent with the statements of a high-ranking Sudanese military source, whom I will call “the general.” The general confirmed to me that secret relations between the two countries continued at the level of the security services, using a civilian front, the “African-Arab Union for Digital Media,” to cover these relations.

The union, which was headed by a board of directors chaired by the wife of Major General Mohamed Atta al-Mawla, the director of the National Intelligence and Security Service, and the executive management of the union included intelligence officers and its executive director was Security Lieutenant Colonel Ghada Abdel Moneim. The union reported directly to the director of intelligence and operated for three years (2016-2019) as a security and military channel facilitating Iran’s operations in Sudan.

All Iranian military and security experts and advisors were brought in under the guise of being media personnel linked to the union. This arrangement continued until the fall of the Bashir government in April 2019, when the union was dissolved and relations severed, only to be resumed again in 2020 under the supervision of Sudanese military intelligence.

In 2016, the Sudanese security community made a case for maintaining military and security relations with Tehran, arguing that Iran was a key part of the axis of resistance, and that they could not abandon this alliance, even if political relations between Tehran and Khartoum ended. For this reason, the security and military establishments worked to maintain these relations for mutual economic and military benefits. This began by enabling members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps involved in military manufacturing in Sudan to train and provide Hezbollah and Hamas with the necessary resources in exchange for economic, military, and intelligence support for Sudan.

After the revolution in Sudan in December 2018 and the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in January 2019, the Military Intelligence and Military Security took over the file of contacts with the Iranians. Here, I find consistency between Hajj’s version of events and the general’s version.

In a related context, it can be noted that the direct supervision of the relationship from the Iranian side was entrusted to Qassem Soleimani until his assassination in January 2020. After that, Brigadier General Esmail Qaani took over the supervision. All communications between the two sides were conducted through the Iranian ambassador to Beirut, Mojtaba Amani, who was injured in the explosion of communications equipment in Lebanon on September 17, according to the Iranian Fars News Agency. Hajj said that it is likely, given the exposure that Lebanon suffers as a result of the superiority of Israeli intelligence over the country’s communications infrastructure, that the point of contact between the two sides has been changed or reassigned to another location.

Despite the fact that the relationship has had its ups and downs, the armed conflict between the Sudanese army and the Rapid Support Forces, along with the Gaza war, gave Tehran an opportunity to make Sudan a new platform for attacks on American, Israeli and Arab interests.

Al-Hajj stressed that Iranian military and intelligence support was a decisive factor in deciding the battle in favor of the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces. He believes that one of the decisive battles was a real turning point, as Iranian support enabled the army to achieve major breakthroughs in the course of the battles. This was particularly evident after the army attacked Omdurman and took control of the radio and television building on March 14, 2024, ending the Rapid Support Forces’ control over it, which had been in place since mid-April 2023.

With the dynamics shifting in Sudan and the changing balance of power, the armed conflict, which escalated into a civil war, reshaped alliances within the country. The conflict brought Islamists back to high-level positions, with their influence growing significantly as the war dragged on. They fought alongside the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces, particularly the Brotherhood battalions linked to the Sudanese Islamic Movement, known locally as the Kizan. Civilian politicians, including those from the Forces of Freedom and Change, a civilian and rebel alliance opposed to military rule, accuse Islamists of controlling the decision-making apparatus within the army after the war. This has largely contributed to the failure of all international and regional efforts to launch dialogue and propose solutions to the civil war, whether through the Jeddah talks, the IGAD initiative, or the Egypt conference.

The course of the war has become unpredictable, said Hajj, who spent 40 years in politics, military service and foreign security. The Islamists are allied with Iran as a state and an ideology, seeking to strengthen Tehran’s power, protect its interests and expand its influence. They have strong ties with other Islamist organizations in the region, such as Hamas, al-Qaeda, Hezbollah and the Houthi movement. These ties deepened and became more intertwined after the war in Gaza and the assassination of Hamas’s political leader, Palestinian Ismail Haniyeh, in Tehran on July 31, as well as a series of Israeli military strikes in Lebanon, which in a month killed 18 Hezbollah leaders, including Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah on September 27.

All of this brings me back to a 2012 book by American intelligence officer Stephen O’Hearn, “Iran’s Revolutionary Guard: The Threat That Grows While America Sleeps.” In the book, O’Hearn asserts that Iran brought Osama bin Laden to Sudan after the IRGC struck a deal with Hassan al-Turabi (1932-2016), the leader of the Sudanese National Islamic Front, in which Tehran would provide millions of dollars for training centers and arms transfers that would turn Sudan into an Iranian launchpad for the rest of Africa.

Today, the Persian strategy of conflict – exporting extremism and terrorism, and strengthening the presence of rogue states – is being repeated, but with new methods and tools.

In this context, a source who claims to have met with a group of American intelligence officers in the late 1990s and before 9/11 confirmed that Sudan would be a central focus of Salafi jihadism. During the Bashir regime, the Muslim Brotherhood believed that they had secured a country ruled by the international organization of the Muslim Brotherhood and were planning to launch from there to control other countries. Therefore, Iran considered Sudan early on as a strategic ally that would help it achieve its ambitions and export its revolution to Mecca, and redirect Muslims around the world to Iran, which claimed that it would lead the Islamic world as a savior from the colonial face of the United States and end the state of Israel.

As midnight approached, the pilgrim began to look tired. I politely suggested that he could rest and we would continue tomorrow. But he just smiled and replied, “Can you guarantee that we will be able to do this session tomorrow? Let’s continue. Maybe someone will read or listen.”

Thus, Alhaj believes that not only have the main actors recently returned, but the conditions are remarkably similar to those in Sudan in the 1990s. Khartoum has been isolated internationally and regionally, and the lack of trust between the Sudanese military and the various parties in the peace negotiations has become evident. The military’s need for new allies with experience operating in complex conflict environments, such as the Iranians, has increased, especially after the losses it suffered during the early stages of the war. Given that it views its battle against the RSF as existential, all of these factors have increased the influence of both the Islamists and the Iranians.

Thus, Hajj concluded, the conditions and actors are in place to recreate the 1990s scene, but this time accompanied by a highly volatile and turbulent African and Middle Eastern environment. To understand the implications of Iranian empowerment in Sudan, Hajj said, one must first examine the broader current landscape of Africa. For example, the continent is undergoing rapid transformations, with increasing challenges to the United States’ capabilities to combat growing terrorism there. These challenges have been exacerbated by four post-2020 coups in African countries: Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Following the withdrawal of U.S. forces in July 2024 from their air base in Niger dedicated to counterterrorism, Central Africa has become a quagmire where local governments struggle against terrorist organizations such as ISIS and Al-Qaeda, as well as sympathizers seeking to foment chaos.

Observing Iranian activity in its early stages may not provide an accurate reading of our current situation. In this regard, the general stated: “Iran has been operating in Africa for many years, and recently Iranian drones reached Ethiopia during the government’s war with the Tigray Front in 2020-2022, and now they are working with the Sudanese army and I do not rule out that they are at risk of falling into the wrong hands.” He confirms that Tehran continues to support the Somali terrorist movement Al-Shabaab and is actively involved with the Islamic Movement in Nigeria, which acts as an Iranian proxy similar to Hezbollah, the Popular Mobilization Forces, and the Houthis.

This comes at a time when Tehran is increasingly seeking to reclaim its centrality and pivotal role in supporting anti-US and anti-Israeli Islamist groups, especially in light of the ongoing conflict in Gaza. The failure of its recent missile attack on Israel on April 13 highlighted Iran’s inability to attack either country from within its territory, reinforcing Tehran’s need to enhance its covert operations and attacks while maintaining deniability.

While Africa is teeming with jihadist fighters, Iran has the expertise, knowledge, and history of organizing and supporting them through various means. Expanding its influence in Sudan amid growing uncertainty and ambiguity would allow Iran to redevelop its infrastructure, enabling it to direct and organize these organizations and groups. This is especially likely to happen if the Sudanese military succumbs to external pressure and transforms from a national institution into a body of diverse military groups similar to the Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq, effectively becoming a proxy for Tehran. In such a scenario, Sudan could revert to a rogue state that threatens regional stability and poses a military and security threat to all its neighbors, with Al-Haj specifically pointing to Egypt and Saudi Arabia as Iranian targets in the medium term.

The Red Sea: The Safe Corridor Knot Between Iran and Its Interests in Sudan

I have often pondered Iran’s strategy of approaching and offering assistance to countries, especially in times of armed conflict. This strategy involves providing support that gives the aggrieved party a sense of importance and the ability to change the balance of deterrence and power, allowing Iran to impose its terms on other demands. This is exactly what happened in Sudan.

Iran’s appetite for expansion and growth in Sudan, Hajj told me, is not only driven by the current circumstances and realities of war, but also by Sudan’s important geopolitical position in the Red Sea environment. In 2012, Iran offered to help Sudan set up air defenses along the Red Sea coast after an airstrike that Israel was accused of carrying out.

Here comes the role of the Houthis in developing the infrastructure through the Iranian concept. Al-Hajj noted that the actual relationship between Sudan and the Houthi movement began five years after the so-called Operation Decisive Storm, which began on March 25, 2015. The main topic of discussion between the two parties was the Sudanese prisoners in Yemen.

Sudanese intelligence was managing communications with Brigadier General Yahya Saree, the Houthi spokesman, and Mohammed Abdul Salam, the chief negotiator, as well as Abu Maitham, the Houthi movement’s external security director who was originally based in Beirut. It is currently unclear whether he is still there after the change in contact points and Israeli strikes targeting known leaders as part of the Axis of Resistance, or if he has moved elsewhere.

Referring to the general who is believed to have been in charge of communications with Iran in 2020, specifically with the Revolutionary Guards. During that period, a set of understandings were reached stipulating that the Houthis would not target Sudan militarily. In return, the Sudanese military intelligence and the General Intelligence Service, with the approval of General Burhan, agreed to allow the smuggling of weapons to the Houthi movement via the Red Sea under the supervision of Sudanese intelligence. And to facilitate the movement of the Houthis via Khartoum Airport to travel outside Sudan after arriving from Yemen via the Red Sea; this included facilitating the arrival and transfer of 17 Houthi leaders from Khartoum Airport on three separate flights to Beirut, as well as treating wounded Houthis in Sudan.

In late 2021, the relationship between the two parties developed, with a focus on the efficient smuggling of drone engines to the Houthi movement via the Sudanese port of Flamingo on the Red Sea. The smuggled shipments included precision spare parts and guidance technology for ballistic missiles arriving via fishing boats anchored in Port Sudan. In addition, the number of Houthis smuggled from Sudan to Beirut has steadily increased to at least five people per week.

Al-Hajj believes that Sudan’s facilitation of the Houthis and Iranians contributed to the development of relations leading to agreements to supply Sudan with drones and train some Sudanese Armed Forces officers, culminating in early 2024 with the formal restoration of full relations between the two countries, as well as increased intelligence and military activities.

The pace of Houthi attacks has begun to take a new direction since entering the fifth phase, according to their media, in terms of the pace of their targeting of commercial ships in the Red Sea. The movement has begun to document its attacks. On October 3, 2024, the Houthi war media showed footage showing the targeting of the British oil tanker Cordelia Moon in the Red Sea, using an unmanned boat. This reveals a new media fact that aims primarily to promote their ideologies and prove the effectiveness of their military option, despite its failure to stop the war in the Gaza Strip.

Al-Hajj continues the narrative in an engaging way, trying to historically link the goals of each event to the events that followed. After the official restoration of relations between the two countries, a senior security officer in charge of supervising the project to supply Sudan with drones, General Al-Sadig, who once served as General Burhan’s chief of staff, traveled to Tehran twice this year, where the old agreement on arms smuggling – the trade in drones and precision missile guidance equipment to the Houthis – was confirmed.

Furthermore, Iran was granted a military base on the Red Sea, ensuring the flow of weapons and military equipment to Hamas. There was also an agreement to deploy a Sudanese liaison officer in Eritrea to facilitate smuggling operations across the Red Sea, as well as an understanding that the Sudanese Armed Forces stationed in Saudi Arabia would not deal with the Houthis, while providing all necessary support and facilities to target Khalifa Haftar’s plans in Libya.

To verify the information of the pilgrim and the narrative he provides, it was necessary to consult the general, who confirmed that by the end of January 2024, two Mohajer-6 drones entered service and began operating from Wadi base, one of the largest military bases in Sudan. These drones are currently participating in military operations.

During the same period, an Iranian ship arrived at Port Sudan carrying four Mohajer-6 drones, along with five 130mm artillery pieces, six 120mm mortars, and a wide range of different munitions. He added that fishing boats crossing the Red Sea are widely used for smuggling weapons, often loaded with fish on the deck while hiding between 600 and 800 assault rifles below deck. Furthermore, larger fishing vessels also carry various types of missiles and spare parts for drones.

He said that after the relationship between the two countries became normal and direct, Iran, through the Sudanese Military Industrialization Authority, provided 300,000 fully equipped military uniforms and surveillance and espionage equipment to the Sudanese army.

Regarding securing the transfer of weapons and military equipment to Hamas, there was coordination between military intelligence and Sudanese intelligence to use the expertise of the Rashaida tribe, which settled in Sudan in 1846. Weapons and military experts are smuggled from Sudan through the Sinai Desert, in coordination with some tribes inside Egypt, all the way to the tunnels leading to Gaza. In this regard, the general, who greatly respects and appreciates the Egyptian leadership, wonders about its decision to support the Sudanese army, saying, “Egypt supports the Sudanese army in its fight against the Rapid Support Forces, based on its need to achieve stability in Sudan and the Sudanese army’s supportive position towards Egypt in its position on the Renaissance Dam, in addition to the historical relations between the two parties,” and he pauses for a moment to atone; “However, Cairo today faces a major challenge in preserving its interests with the Sudanese army after the war pushed it to ally with the Iranians and Islamists who have come to enjoy great influence within the army, especially since Cairo has suffered for decades from radical Islam and the Muslim Brotherhood’s projects against the Egyptian political system, which intersect greatly with the Iranian project, whether towards the region as a whole or Egypt in particular, and has paid a heavy price in Sinai because of the Takfiris,” he added.

Therefore, Cairo must determine its position and assess the repercussions of the Sudanese army regaining control over the country’s geography, which may lead to the presence of a radical Islamic force that may feed on the one hand the Muslim Brotherhood’s ambitions to rule Egypt, and the attempts of terrorist organizations to regain their previous presence in Sinai.” The general took a deep breath, looked me directly in the eye and said firmly: “Egypt must decide this battle and take the lead from the Iranians.”

For a specialist researcher who wanted to verify the sources, it was necessary to find someone within the Sudanese Foreign Ministry who could discuss the Sudanese Foreign Minister’s visits to Tehran, the first of which was on February 5, 2024. During my time in Khartoum, I wanted to meet an active diplomat working in foreign affairs, and so through research and mutual friends, one name repeatedly came up in diplomatic circles, whom I will refer to as “the diplomat.”

The delegation accompanying the minister reportedly included representatives from the National Intelligence and Security Service and the Al-Baraa Bin Malik Battalion, also known as the Al-Baraa Bin Malik Brigade or the “Shadow” Battalions. This armed group has an extremist ideological affiliation and maintains a network of relations with Sudanese armed groups that cooperate with the Sudanese army against the Rapid Support Forces.

The diplomat also noted an implicit and direct agreement between the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Sudanese General Intelligence Service and Military Intelligence that allowed both countries to withdraw from the agreement. The Al-Baraa bin Malik group was tasked with carrying out armed military operations in the Red Sea, while maintaining a connection with the Revolutionary Guard similar to that of Hezbollah and the Houthis, as well as some factions in Iraq.

This is consistent with what the general told me: “A number of members of the Al-Baraa bin Malik Battalion were trained to operate drones and explosive-laden sea boats in Iraq and Lebanon.” In addition, the foreign minister’s visit to Tehran resulted in an agreement to set up a drone and suicide boat production line in Port Sudan under Iranian supervision to supply the Houthis and Hamas with these types of aircraft. In return, Iran was granted one million acres of agricultural land from Sudanese territory.

As soon as the name of the Bara bin Malik Battalion appeared alongside a group of extremist armed groups, many questions arose in my mind that contribute to understanding the security chaos that is taking place in the Middle East and Africa, and which will continue to unfold. It was necessary to ask about the existence of ISIS: is it already present on the ground and fighting alongside the Sudanese army? Is it generously funded and has access to new military technologies?

In this regard, many sources I spoke with agreed that the relationship between the Sudanese Islamic Movement and extremist Islamist groups is close and advanced. At various times, these groups have provided funding, training, protection and intelligence. Through institutions such as the Quran Society, the Islamic Call Organization, the University of Africa, the University of Omdurman Islamic, the Al-Birr and Al-Tawasul Organization, the Madkar Organization and the Foreign Students Union, they provided a ready infrastructure for engaging with and absorbing the ideas of the terrorist organization ISIS, which has played a public role in military operations since the beginning of the war. This is evident from the confession of politician Mohamed Ali Al-Jazouli, who also serves as the Secretary-General of a Sudanese Islamist group, when he was arrested by the Rapid Support Forces in May 2023.

In analyzing the extremist scene in Sudan and tracking the movements of wanted extremists, it appears that a large number of ISIS members from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan – estimated at around 6,000 – have been invited to fight alongside the Sudanese army under the guise of studying at Sudanese universities.

Furthermore, a researcher specializing in countering violent extremism in Sudan told me that a man named Saddam, who uses the nom de guerre “Abu Abdullah,” is living in Sudan. Despite his involvement in the January 1, 2008, killings of American citizens John Granville and Abdel Rahman Abbas Rahma, Saddam has never been captured, has been smuggled into Iraq, then Syria and Libya, and is now fighting alongside the Sudanese military in Omdurman, the country’s second-largest city.

When I presented the information I had to Al-Hajj, asking for confirmation or denial, I was surprised when he said, “If you want to get rich, all you have to do is show the Americans Sudan.” In a sarcastic tone, he added, “Do they even know about us?” He then explained that most of the individuals wanted under the U.S. State Department’s Rewards for Justice Program are here in Sudan—including Al-Dasouki, nicknamed “Khomeini”; Sheikh Jibril; Imam Bilal; Hashim Arabi, a former colonel in Syrian intelligence; and Hisham Al-Tijani, the student leader of the Sudanese Student Association, all of whom were active members of the terrorist organization ISIS.

While in Khartoum, I met with one of the diplomats active in foreign affairs. As is often the case, everyone in this country wants to find a way out of the crisis and get messages out to the world, but they fear assassination. The diplomat tried to explain why. He said: “In the period before the outbreak of war in Sudan, there were attempts by the head of the military council, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, to improve relations with moderate countries in the region and cleanse the country of the legacy of Bashir and the Islamic Front. In October 2020, Khartoum agreed to normalize relations with Israel, and two months later the United States removed Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism. But that did not last. Sudan is a country where all contradictions come together, and it is impossible to plan for the future because of the intertwined data, the complexities and the multiplicity of actors who come from different and often conflicting backgrounds.”

I tried to reach out to anyone in the RSF to get their account and perspective on what was happening in Sudan, but I was unsuccessful. In fact, I was strongly advised against contacting them due to the complexities of the situation. They warned me that asking questions and possibly misinterpreting their understanding of my position could lead to “challenges” that would be difficult to deal with.

How to analyze the implications of Iranian control over Sudan

Iran’s clear ambition to control Sudan has serious and long-term consequences for the security and economic interests of the United States and its Arab partners, especially Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Iranian control of Sudan could turn it into an active and influential state regarding the fate of a vital trade corridor for Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and Israel.

The negative effects of Iran’s presence are evident in the recent military activities of the Houthis, who now have a route for smuggling weapons, transferring leadership, advanced technology and spy equipment, creating a new terrorist hub that will be difficult to dismantle. Moreover, the geographic depth of the Iranians and the Houthis is increasing. Given that Sudan is the gateway to Africa, Iranian influence will continue to expand there.

It cannot be underestimated that the Iran-Sudan agreements have allowed Tehran to gain full control of the Red Sea, which threatens maritime navigation in both the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea. Consequently, Saudi interests are exposed to multiple levels of military, security and economic risks. This includes development projects under Saudi Vision 2030, where the Saudi coast along the Red Sea plays a pivotal role, as well as the NEOM project and the Red Sea Coast Development Project, both of which are part of Saudi Arabia’s plans to diversify its economy away from oil dependence by positioning itself as a hub for tourism, entertainment and foreign investment.

In addition, there is a direct impact on the Egyptian economy, as the Suez Canal handles 15% of international shipping traffic, 30% of container trade worldwide, and 40% of trade between Europe and Asia . Suez Canal revenues have fallen sharply due to the Houthi attacks, to around $2 billion in the 2023-24 fiscal year , as shipping traffic diverts around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa.

In the same vein, the Iranian-Sudanese rapprochement has contributed to Sudan’s distancing itself from supporting Saudi interests. As previously mentioned, Sudan stood in solidarity with Saudi Arabia and cut ties with Iran after the storming of the Saudi embassy in Tehran in 2016. However, it has become clear that Sudan’s support was superficial and insincere. In addition, Sudanese forces participated in the Saudi campaign against the Houthis in Yemen, which also seemed to serve Iranian interests.

We are facing a major shift in the expansion of Iranian influence in Sudan, which poses a geopolitical threat to Saudi Arabia. This may be Iran’s ultimate goal. The Sudanese army’s lack of seriousness in responding to Saudi pressure to stop the war only increases the turmoil in the Red Sea and negatively affects Saudi national economic and development projects.

Moreover, the expansion of Iranian influence in Sudan increases pressure on its military and weakens its position against the establishment of an Iranian naval base, especially given the intensity of the civil war, which increases the military’s need for Iranian support. This would put the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps just 200 miles (320 kilometers) from the Saudi coast . Also, the presence of an Iranian naval base would enhance Iran’s intelligence and reconnaissance capabilities in one of the busiest sea lanes in the world. Imagine how much more Iran could achieve than the role it plays in providing the Houthis with data on passing ships, enabling them to successfully carry out their attacks .

Conclusion

Today, after many interviews with people whose names I have withheld for their protection and safety, I believe that we are on the verge of confronting a violent extremist terrorist axis that targets all countries in the world that do not align with the Iranian project.

In the case of Sudan, its maritime borders could put the Red Sea at the mercy of Iranian-backed terrorist groups. It would be unrealistic for the United States to turn a blind eye to this threat, especially at a time when it has mobilized a large part of its naval military force to combat Houthi threats to international shipping. The Houthis have gained support and assistance from Iran, particularly in their use of missile and drone arsenals against military and commercial vessels, as well as Israeli targets. Iran continues to seek to influence the dynamics of the Red Sea, by influencing the Bab al-Mandab Strait and establishing a foothold along its coast.

Moreover, Iran’s growing presence in the Red Sea poses an existential threat to energy supplies and utilities, a previous goal of Iran when it enabled the Houthis to target Saudi facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais in 2019. In addition, the Houthis have attacked several oil tankers in the Red Sea during the escalation of the war in Gaza. In February 2024, the British cargo ship Robimar was hit by a Houthi ballistic missile off the coast of Yemen, threatening an environmental disaster due to a potential oil spill that extended 18 nautical miles.

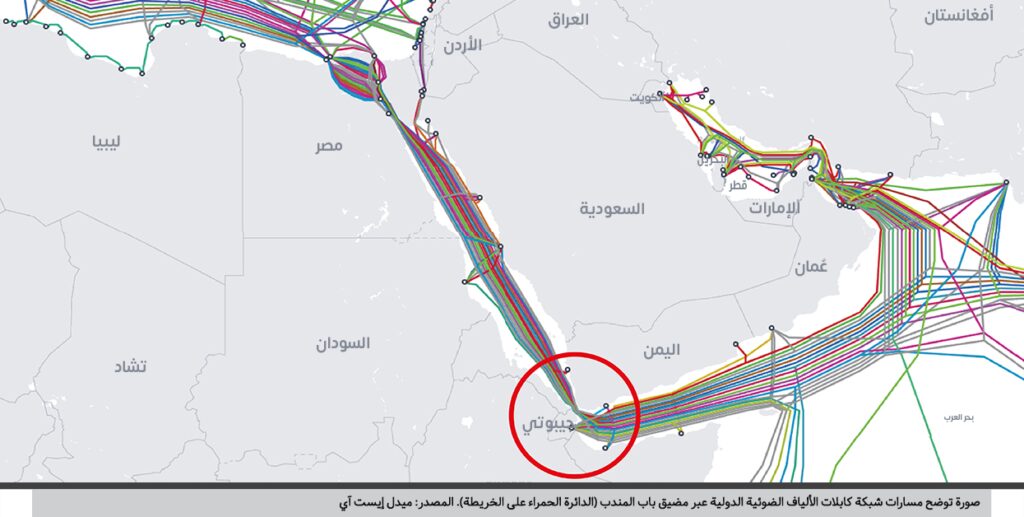

However, Iranian and Houthi activity in the Red Sea has implications that extend beyond commercial and energy security. There are real concerns about threats to global digital infrastructure, with underwater cables potentially becoming targets for Iran and its proxies. The Red Sea bed hosts 16 fiber optic lines, which together account for 17% of all international data transmission lines . “The threat from the Houthis to cut the underwater cables is serious,” said a military source, “and has been discussed between Sudanese intelligence and the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.”

Furthermore, the Houthis’ control extends to the Bab al-Mandab Strait, one of the three choke points for cables around the world, connecting Europe, India, and East Asia. Contrary to false assumptions that the Houthis lack the technical and military capabilities to damage underwater cables, they have demonstrated remarkable superiority during their engagement in the Gaza Strip, particularly after targeting Israel in mid-September 2024 with a “hypersonic” missile that traveled 1,300 miles (2,040 kilometers ) in 11 and a half minutes, according to Houthi military spokesman Yahya Saree.

On the other hand, cutting underwater cables, which are usually no thicker than a garden hose, does not necessarily require any special expertise, trained personnel or even professional divers. Some cables are located in shallow waters as deep as 100 meters . Let’s not forget that three divers were arrested in Egypt in 2013 for trying to cut an underwater cable near the port of Alexandria.

The risk of damage to underwater cables is perhaps even more threatening than maritime piracy. The Red Sea carries an estimated 17% of the world’s internet traffic along its fiber pipelines, making it a rich target for the Houthis. Damage to these cables could have enormous consequences for the global economy, as well as civil, military, and financial information services.

Alarm bells were set off in December 2023 when Houthi-linked Telegram channels published a map of underwater communications cable networks in the Mediterranean, Red Sea, Arabian Sea and Gulf accompanied by a threat: “Yemen appears to be in a strategic location, with internet lines connecting entire continents – not just countries – passing nearby.”

Another channel linked to Lebanon’s Hezbollah posted a post asking: “Did you know that internet lines connecting the East and West pass through the Bab al-Mandab Strait?” This prompted a five-bell alarm by telecom companies regarding possible sabotage by the Houthis .

However, the risks to underwater cables may not necessarily stem from deliberate actions. The Houthis’ fierce naval war in the Red Sea could inadvertently damage these cables. When the British cargo ship Robimar, which was hit by a Houthi missile attack off the coast of Yemen in March this year, evacuated its crew and dropped its anchor in deep water. The anchor tangled in three underwater cables and dragged them along the seabed, disrupting internet access for millions of people, from nearby East Africa to thousands of miles away in Vietnam.

Finally , it is important to highlight the humanitarian cost of the war. According to a report by the International Rescue Committee, since April 2023, the ongoing war has killed 150,000 people, a figure far higher than the officially reported death toll of 15,000. Furthermore, 12 million people have lost their homes, with 10 million internally displaced and 2 million fleeing to neighboring countries. In addition, 18 million people face severe food insecurity amid shortages of food, water, medicine and fuel.

All of the above not only raises the question of Iran’s intervention in Sudan and its ability to help the Sudanese army achieve victory and regain control of the country. It also raises the question that has never been asked: whether the United States and the Middle Eastern countries are prepared to bear the consequences of Iranian intervention in another conflict in the region, especially in a country whose coastline extends for about 670 kilometers along the Red Sea.

This was the only question that the pilgrim, the general, and the diplomat did not even attempt to answer, except by shrugging their shoulders in an expression of their despair and weariness of the world.

As I was editing and reviewing this article, on October 1, Iran launched 180 ballistic missiles at Israel in response to the assassinations of Hamas political bureau chief Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran and Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut. At the time, Hezbollah was facing structural, logistical, and organizational challenges due to Israeli strikes targeting its leaders and weapons storage sites.

The latest Iranian attack may differ from its combined attack on April 14 in terms of its range of reach, which took about 15 minutes, the few interceptions of missiles compared to the first attack, which shot down about 99% of the flying objects, the targeted sites, which are directly linked to the course of the war in the Gaza Strip and Lebanon, and its achievement of the element of surprise, as Iran entered a state of complete silence before it, and its indicators were monitored by the Americans and Israelis hours before its implementation.

This brings us back to the idea that the space given to Iran through the Sudan gateway has contributed to the development of its missile program. What would the Hajj, the General, and the Diplomat say? I think they would agree with me that October 1 is just a deadly example of how Tehran has taken advantage of the period of freedom of movement it has enjoyed in Sudan in recent years.