The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

Sudan. The SAF launched an offensive to relieve several besieged units in Khartoum. Iranian or Turkish drones likely helped set conditions for the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) offensive. The end of the rainy season in Sudan will likely increase fighting across the country in the coming months, which will compound the humanitarian crisis and continue to stall peace talks.

Somalia. The Somali parliament is attempting to impeach the foreign minister over his support for Somalia’s growing military cooperation with Egypt, highlighting Somalia’s internal fissures over the response to the ongoing Ethiopia-Somalia dispute. Sacking the foreign minister would likely further delay Turkish-led negotiations between Ethiopia and Somalia. Growing external military engagement with Somalia has increased the risk that the dispute could escalate into a direct or proxy armed conflict.

Benin. Benin claimed to foil an elite coup. The thwarted attempt highlights Benin’s political fragility, which risks undermining US development and security assistance. A successful coup would jeopardize US cooperation with Benin, which is a key part of US efforts in the Gulf of Guinea to help contain the Sahelian Salafi-jihadi insurgency.

Russia. Russia is continuing to expand development and political cooperation in the Sahel as part of its strategic efforts in Africa, but it is facing challenges in continuing its phased implementation of a power plant construction project in Burkina Faso.

Assessments:

Sudan

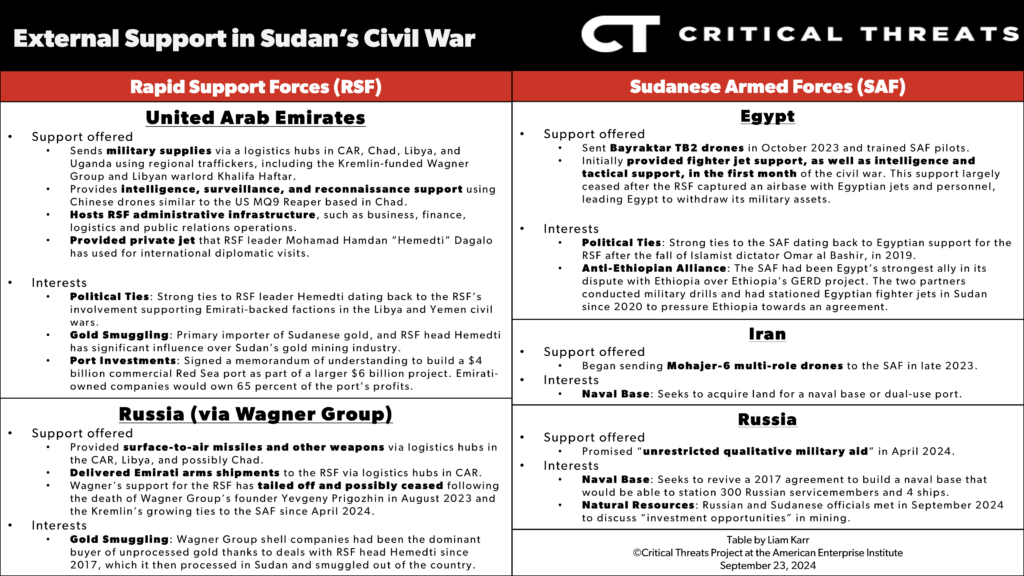

The SAF launched an offensive to relieve several besieged units in Khartoum. The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) launched the offensive on September 26 with shelling and air strikes on Rapid Support Forces (RSF) positions on the east side of the Nile River.[1] SAF units attacked from the west bank of the Nile in Omdurman, captured several key bridges over the following days, and established beachheads on the east side of the River.[2] The Nile had been a stalemate line between the SAF and RSF in Omdurman for more than a year. The RSF controlled the east bank of the Nile, most of Khartoum, Sharq al Nile, and Khartoum Bahri districts, and the southern half of the Omdurman district.[3] The SAF had controlled the west bank and the northern half of the Omdurman district.[4]

The offensive likely aims to relieve besieged SAF positions. SAF forces captured the Halfaya Bridge on September 28 and linked up with besieged SAF units that the RSF had besieged in the Kadroo Military Area.[5] The SAF also seized the White Nile and Ingaz Bridges in the initial stages of the offensive on September 26. These gains put SAF forces across the Nile and within four miles of besieged SAF positions around the SAF headquarters.[6]

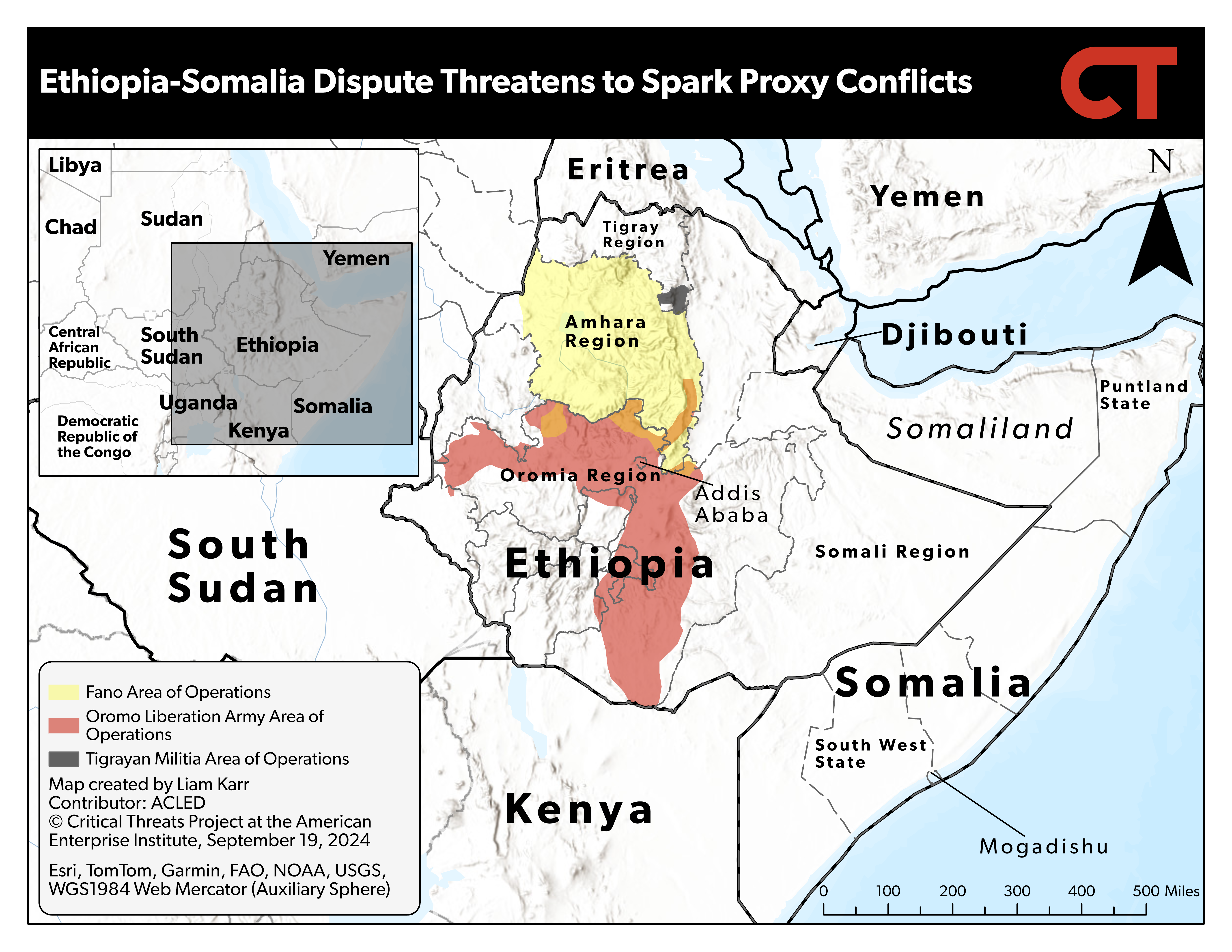

Iranian or Turkish drones likely helped set conditions for the SAF offensive. Sudan War Monitor reported that “drone attacks and artillery attacks (aided by drone spotters) have made the RSF’s defense of the Halfaya Bridge more difficult” in recent months.[7] This is because the access road to the bridge crosses open farmland, exposing RSF forces to drone strikes and artillery fire. The SAF began receiving Mohajer-6 multi-role drones from Iran in late 2023.[8] The Mohajer-6 drones have already helped the SAF in other clashes around the capital, with Sudanese media reporting they played a “decisive role” in the SAF’s offensive to retake RSF-held areas in Omdurman in early 2024.[9] Reuters also reported in April 2024 that the SAF used Iranian drones to “monitor RSF movements, target their positions, and pinpoint artillery strikes,” the same way the SAF used drones around Halfaya Bridge.[10] The SAF also acquired Turkish TB2 Bayraktar drones from Egypt in October 2023, but it is unclear how the SAF has used these drones.[11] CTP cannot verify which drones have been used in the latest offensive.

The usefulness of Iranian drones will presumably give Iran more leverage as it seeks to gain a Red Sea naval base concession from the SAF. Iran has used its support to try and obtain an agreement for a naval base or dual-use port in Sudan in exchange for continued aid and a helicopter-carrying ship.[12] The SAF has rejected Iran’s overtures to avoid alienating its historical allies—Egypt and Saudi Arabia—as well as Western countries.[13] An Iranian naval base at Port Sudan would support Iran’s and its Axis of Resistance’s power projection and attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

Figure 1. External Support in Sudan’s Civil War

Source: Liam Karr.

The end of the rainy season in Sudan will lead to an uptick in fighting across the country in the coming months, which will compound the humanitarian crisis and continue to hamper peace talks. Sudan War Monitor assessed that the three-month rainy period from July through September hampered off-road movement and led to a decrease in combat outside of urban areas since July.[14] The RSF launched several offensives in different parts of Sudan in the fourth quarter of 2023, including Darfur, Kordofan, and south of Khartoum.[15] Fighting between the RSF and the SAF with allied rebels has already escalated around El Fasher, the provincial capital of North Darfur province in the Darfur region, since late September.[16]

Figure 2. The Situation in Sudan

Note: SPLM-N refers to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North, a pro-SAF rebel group. SLA refers to the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, a pro-SAF rebel group. SLA-TC stands for Sudan Liberation Army–Transitional Council, a neutral breakaway faction of the SLA. SSPDF refers to the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces.

Source: Thomas van Linge.

New offensives would likely stall peace efforts as both sides attempt to maximize their negotiating position. The United States attempted to resume peace talks in August after US- and Saudi-mediated talks ended without an agreement in December 2023.[17] The SAF actively boycotted the talks, which it publicly said was because of the involvement of the United Arab Emirates in the discussions, which provides military equipment and funding to the RSF.[18] Sudan War Monitor also said the SAF’s boycott is at least partially because the SAF anticipates that new weapons and recruits will enable it to turn the tide and achieve a military victory.[19] The SAF’s absence from the talks contributed to the efforts reached no crucial breakthrough, although international stakeholders did advance some humanitarian efforts. There is currently no date for future talks, but US President Joe Biden called on the SAF and RSF to resume talks during his address to the UN General Assembly in September.[20]

An increase in fighting will exacerbate Sudan’s dire humanitarian situation. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs reports that fighting has already displaced over 10 million people, over 2 million of whom have left the country.[21] More than half the country’s population also faces “acute hunger,” and over 750,000 people are on the brink of famine.[22] Local volunteers claim that the war is killing 10 to 15 civilians daily in Khartoum Bahri district alone and that the district is approaching famine.[23] El Fasher, surrounding areas, and nearby refugee camps were already facing famine conditions since fighting around the city began in April 2024 due to both sides refusing to cooperate with aid efforts.[24] The UN called for an end to the RSF siege and fighting around the city in late September and accused both sides of carrying out human rights abuses against civilians.[25] The UN also warned that the fall of El Fasher to the RSF would likely lead to ethnically targeted violence, similar to the RSF’s ethnic cleansing campaign after capturing El Geneina, the provincial capital of West Darfur province.[26]

The international community is not meeting the current challenge, much less a worsening situation. The United States and other international stakeholders agreed in August to open three humanitarian corridors that US officials say will help food, medicine, and other lifesaving services to 20 million people in Sudan.[27] However, other multilateral initiatives to address the humanitarian and refugee crisis are severely underfunded. The 2024 Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan for Sudan is only half funded, with the UN still $1.3 billion short on funding.[28] The $1.5 billion 2024 Sudan Regional Refugee Response Plan, which aims to support the fragile neighboring countries taking in Sudanese refugees, is only 25 percent funded.[29]

Somalia

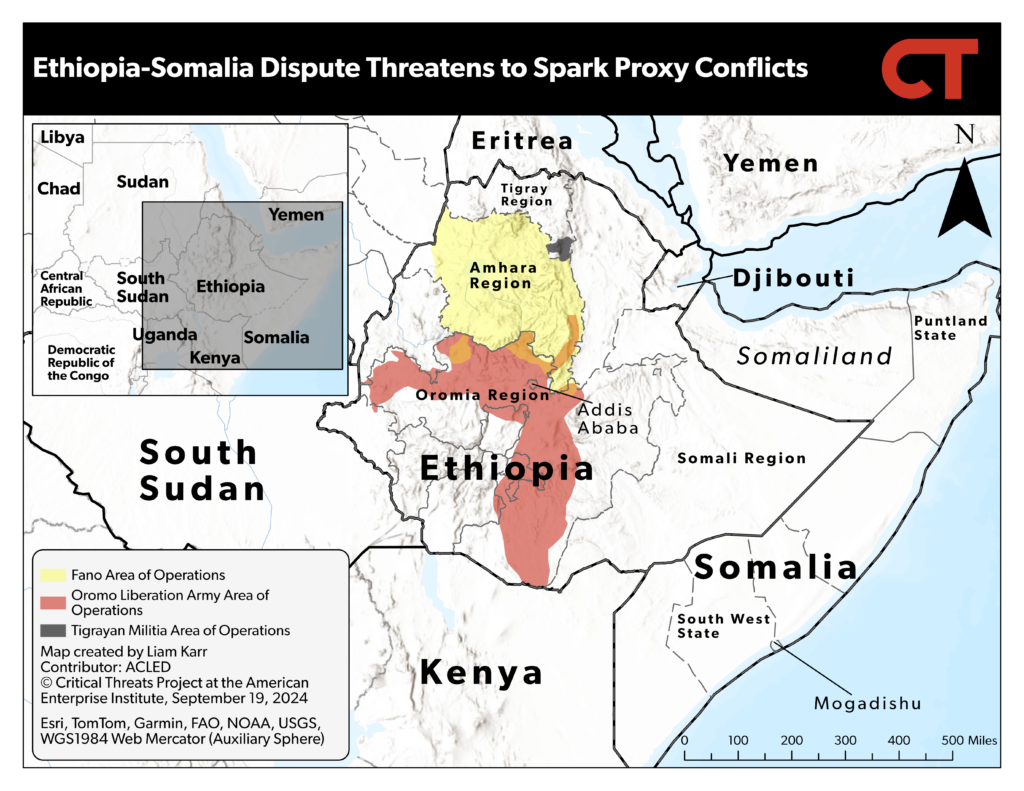

The Somali parliament is attempting to impeach the foreign minister over his support for Somalia’s growing military cooperation with Egypt, highlighting Somalia’s internal fissures over the response to the ongoing Ethiopia-Somalia dispute. Over 180 members of Somalia’s parliament submitted a proposal to impeach Somali Foreign Minister Ahmed Fiqi on September 28.[30] Somali media reported that a debate over the proposal is expected to happen “soon.”[31] Somali media cited Fiqi’s support for Egypt’s military deployment to Somalia as a possible cause of the impeachment proposal.[32]

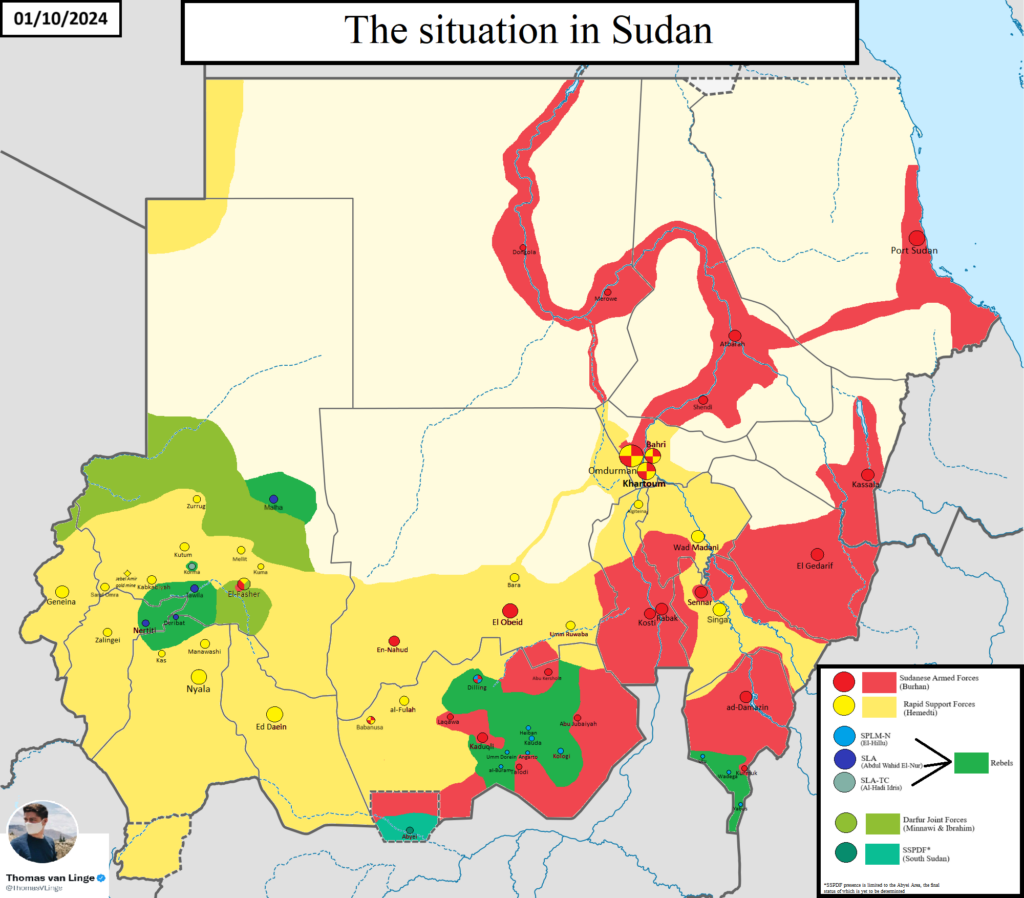

Figure 3. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

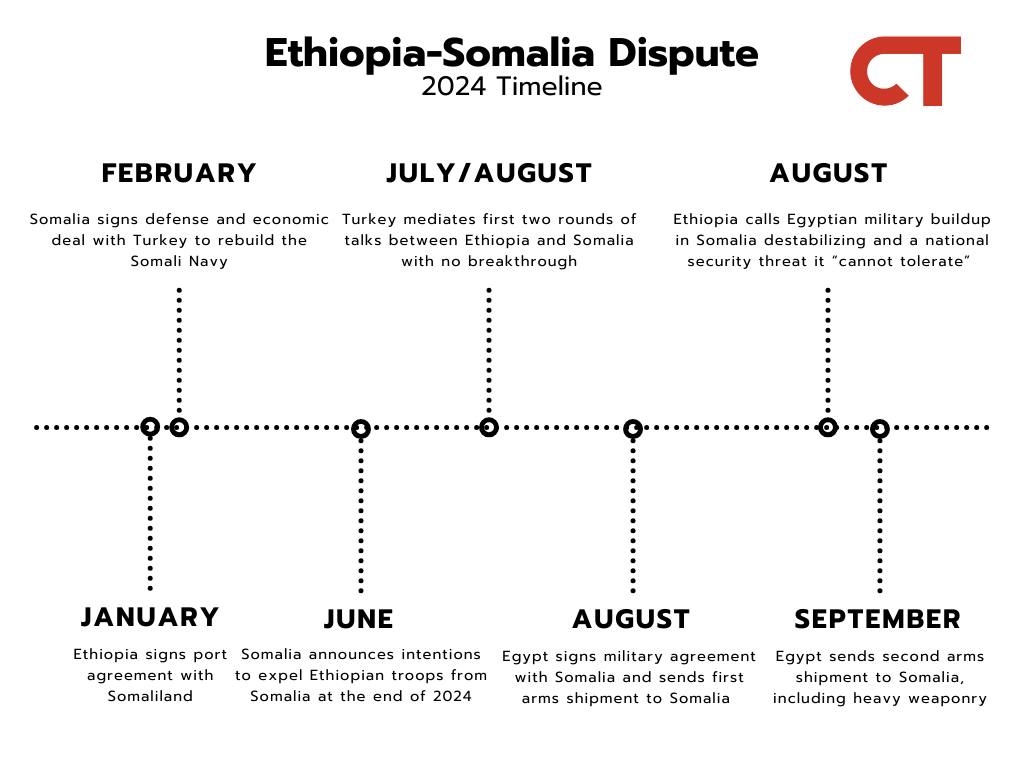

The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has increased military cooperation with Egypt as an alternative partner to replace Ethiopian forces and counter Ethiopia after Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding for a naval base with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region in northern Somalia in January 2024.[33] The SFG has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty and since said it will expel the 3,000 Ethiopian troops in Somalia as part of the African Union (AU) mission when the mission concludes at the end of 2024 and the additional 5,000–7,000 Ethiopian troops that are in Somalia on a bilateral basis.[34] Egypt and Somalia signed a defense cooperation agreement when Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud visited Egypt in August. Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi confirmed that Egypt will contribute troops to the revamped AU mission in Somalia that is scheduled to begin in 2025.[35] Egypt has already sent two arms shipments to Mogadishu since August 2024 that included small arms and heavy weapons such as antiaircraft guns and artillery.[36] Egyptian media also claimed that Egypt deployed 1,000 troops to Somalia in August, but Somali officials have denied these reports.[37]

Tension is also growing between the SFG and local leaders and politicians in Somalia’s South West State over the SFG’s plan to expel Ethiopian soldiers and replace these soldiers with Egyptian forces.[38] Over 20 members of parliament from South West State rejected the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces following protests in the state against Egyptian deployments in August 2024.[39] The SFG has retaliated against politicians from the area speaking out against the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops. The SFG suspended flights to South West State and barred some officials from traveling there in September.[40] Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud fired his special envoy for health and nutrition—who was a member of parliament from South West State—on September 1 after the envoy voiced support for Ethiopian troops remaining in Somalia and warned against bringing the Nile conflict (i.e., the dispute over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam) to Somalia.[41] Somali media reported on October 2 that Mohamud is holding closed-door talks with the South West State president on the presence of Ethiopian troops on the sidelines of the ongoing National Consultative Council session in Mogadishu.[42]

Sacking the foreign minister would likely further delay Turkish-led negotiations between Ethiopia and Somalia. Fiqi represented Somalia in talks with Ethiopia in July and August.[43] A potential impeachment would further delay the progress of already stalled negotiations. There was a three-month delay between the former foreign minister’s resignation in December 2023 and Fiqi’s appointment in April 2024.[44] The impeachment proposal also did not include a recommended replacement for Fiqi.[45] Turkey was stipulated to lead a third round of negotiations on September 17, but Turkey postponed the negotiations over scheduling conflicts.[46] The Ethiopian foreign minister and Fiqi expressed optimism about a deal during the last round of talks in August, however. The Turkish foreign minister said there was “convergence on some major principles” since the July talks.[47]

Growing external military engagement with Somalia has increased the risk that the dispute could escalate into a direct or proxy armed conflict. Egyptian-Somali military cooperation is meant to combat al Shabaab while threatening Ethiopia. Egypt’s foreign ministry spokesperson said in late September that its arms shipments aimed to support Somalia to “combat terrorism and preserve its sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity.”[48] The latter objective suggests the shipment is at least in part to counter Ethiopia’s port deal with Somaliland, which Somalia has said violates Somalia’s territorial sovereignty.[49] CTP has previously noted that some of the arms Egypt has sent, particularly heavy weaponry such as anti-tank and antiaircraft artillery, is meant for use against Ethiopia, as al Shabaab lacks the capabilities to warrant such weaponry.[50] Fiqi also threatened in September to establish contact with insurgents in Ethiopia if Ethiopia followed through on its port deal with Somaliland.[51]

Figure 4. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute Threatens to Spark Proxy Conflicts

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Ethiopia may also be arming actors more favorable to Ethiopia’s presence in Somalia to buffer against the Egyptian deployments. Somalia said that Ethiopia shipped weapons to Baidoa, the de facto political capital of South West State, without specifying the timeframe of the shipment.[52] The Somali government accused Ethiopia of sending two lorries carrying weapons to the semiautonomous Puntland region in Somalia in late September. Puntland and the Somali federal government have been at odds since April 2024, when Puntland announced it would function as an independent government unless the Somali government addressed its grievances on Somalia’s constitution.[53] The president of Puntland was notably the only state president absent from the National Consultative Council session in Mogadishu on October 2, underscoring the large divide between Puntland and the federal government.[54]

Benin

Benin claimed to foil an elite coup. The thwarted attempt highlights Benin’s political fragility, which risks undermining US development and security assistance. Beninese security forces arrested prominent businessman Olivier Boko, Commander of the Republican Guard Djimon Dieudonné Tévoédjrè, and former sports minister Oswald Homéky on September 24 and 25 in connection to a coup conspiracy. [55] Boko led the conspiracy and worked with Homéky to convince Tévoédjrè to launch the coup. Homéky paid Tévoédjrè $2.5 million and opened Tévoédjrè a bank account with $177,000 in it, expecting the republican guard to carry out the coup on September 27.[56]

Boko and Homéky likely plotted the coup due to their political ambitions and grievances. Boko was a close partner of President Patrice Talon, who had known Talon for more than 20 years.[57] However, the France-based outlet Jeune Afrique reported that multiple internal sources claimed the relationship deteriorated in recent months, after Boko expressed interest in succeeding Talon in the next presidential election, scheduled for 2026.[58] Talon promised not to run for a third term but strongly warned Boko and other allies against brazenly aligning for succession.[59] Talon pushed Homéky to resign after Homéky publicly supported Boko as Talon’s successor in October 2023.[60]

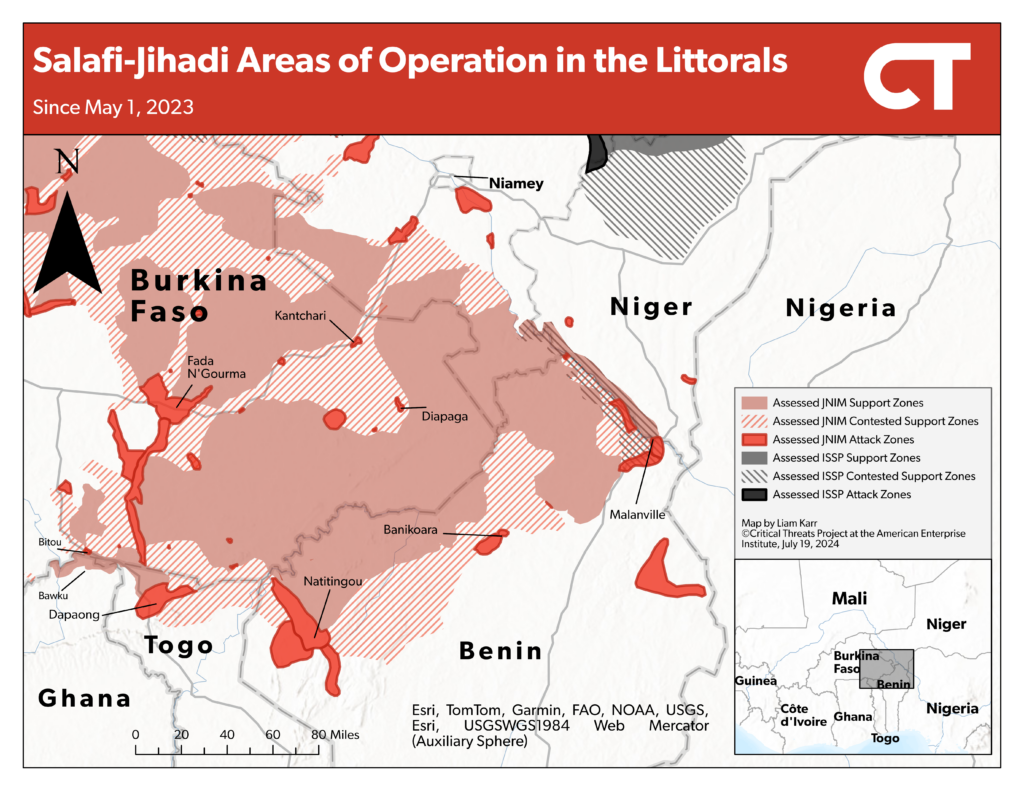

A successful coup would jeopardize US cooperation with Benin, which is a key part of US efforts in the Gulf of Guinea to help contain the Sahelian Salafi-jihadi insurgency. Section 7008 of the US Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2021 requires the United States to end nearly all non-humanitarian assistance to coup governments until a transition back to civilian and constitutional rule is agreed upon.[61] The law specifically ends bilateral economic assistance, international security assistance, multilateral assistance, and export and investment assistance.[62] This law caused the United States to cut cooperation with the Nigerien government after officially declaring the July 2023 coup a coup in October 2023. The end of US cooperation with Niger contributed to the Nigerien government eventually annulling defense deals with the US in March and fully embracing alternative partners, such as Russia and Turkey.[63] Coups in neighboring Mali in 2020 and 2021 and Burkina Faso in 2022 also installed anti-Western juntas that have decreased cooperation with the West in favor of pro-authoritarian partners.[64]

The United States named Benin as key in bolstering resilience to security threats in West Africa and is heavily engaged with Benin to strengthen social coercion and effective governance via programs such as the US Global Fragility Act (GFA) and the US-German Coastal States Stability Mechanism (CSSM).[65] Both initiatives aim to enhance security and conflict prevention through political, humanitarian, and defensive efforts. Beinin is currently one of five coastal West African countries that receive support from the GFA, which supports long-term plans to increase community resilience and address the root political causes of instability.[66] The program is a whole-of-government plan that provides locally attuned development, political, and security assistance through the US Department of State, Department of Defense, and Agency for International Development (USAID).[67] USAID is also helping fund CSSM, which has helped launch discussions and workshops with community members, security forces, and government authorities in northern Benin to improve local resiliency, collaboration, and stability.[68]

Benin has also emerged as one of the main US defense partners in West Africa since the United States decreased security cooperation Niger following the Nigerien coup in July 2023 and fully withdrew in September 2024.[69] The United States maintained roughly 1,000 soldiers across two bases that helped train, advise, and provide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support for French and Nigerien troops.[70] The Wall Street Journal reported in September that the United States is undertaking a $4 million refurbishing of an airfield in Parakou, Benin.[71] The project aims to refurbish taxiways, install aircraft shelters, and accommodate US helicopters. The Wall Street Journal also reported that US Africa Command also has helicopters and medics stationed in Parakou to evacuate wounded Beninese soldiers fighting al Qaeda and Islamic State-affiliated insurgents in northern Benin near the Burkinabe and Nigerien borders and a special forces team stationed in Cotonou to advise Beninese troops.[72] However, US officials have emphasized that the United States aims to maintain a lighter footprint across the Gulf of Guinea than it had in Niger.[73]

Figure 5. Salafi-Jihadi Areas of Operation in the Littorals

Source: Liam Karr.

Russia

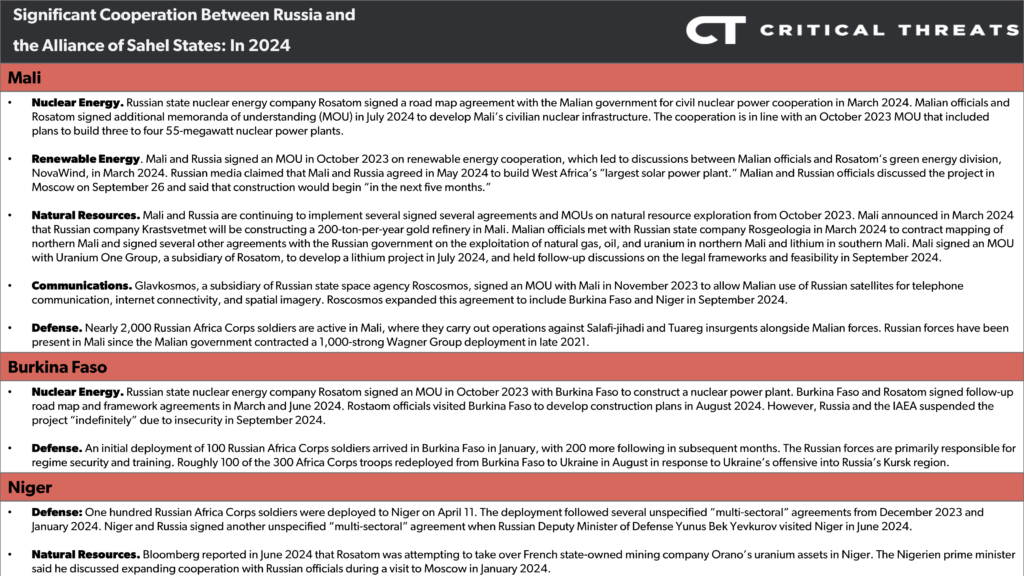

Russia is continuing to expand development and political cooperation in the Sahel but is facing challenges in following through on a nuclear power agreement in Burkina Faso. Malian and Russian officials engaged in another round of discussion on planned joint solar and lithium projects during meetings in Moscow on September 26 as part of a phased implementation of base agreements signed in October 2023.[74] Malian officials said the construction of what Russian media labeled as West Africa’s “largest solar power plant” would begin in the next five months.[75] Russia and Mali also signed an agreement calling for a ban on militarization in space on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly on September 27.[76] Burkina Faso will also hold a forum in Moscow from October 8 to 11 to increase Russian investment.[77]

Figure 6. Significant Cooperation Between Russia and the Alliance of Sahel States

Source: Liam Karr. Individual sources available upon request.

Russia uses its engagement with the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) to build leverage and advance its strategic aims of securing economic concessions and political allyship that help it mitigate Western pressure. The AES (l’Alliance des États du Sahel in French) comprises the three pro-Russian juntas in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. The Kremlin is the primary security partner and regime protector for all three countries and has used this initial security cooperation to grow economic and political ties.[78] Russia uses development investment and general economic cooperation to create export markets and gain access to or stakes in crucial natural resource deposits, which alleviates Western economic pressure.[79] These projects also make recipient countries reliant on Russian expertise, financing, and tech.[80] Russia also uses its relationship with the juntas to gain their support and boost its international political legitimacy on multilateral issues and agreements, such as its ban on militarizing space.

Figure 7. Russia’s Strategy in Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

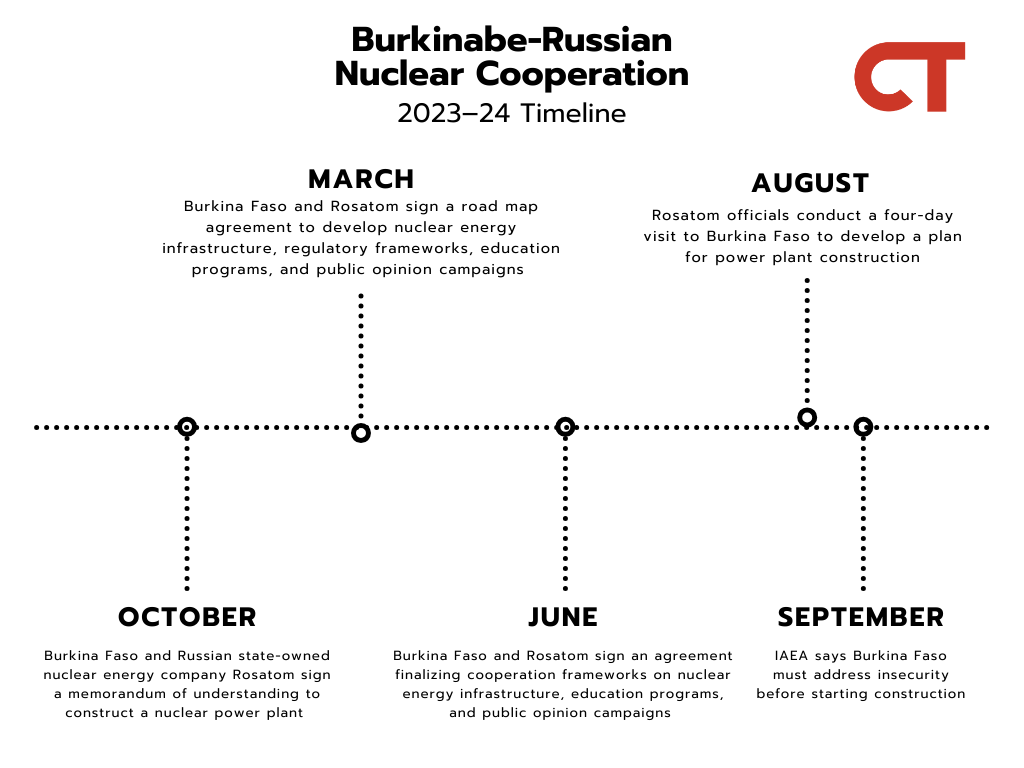

However, Russia faces challenges in continuing its phased implementation of plans to construct a power plant in Burkina Faso after the IAEA said Burkina Faso must address its deteriorating security situation before starting construction. Mikhail Chudakov, the current deputy director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and director of the Moscow Centre of the World Association of Nuclear Operators, said on the sidelines of a Russian energy summit on September 26 that the Burkinabe junta “must end all clashes in the north of the country” in order to start construction.[81] Chudakov encouraged Burkina Faso to carry out a “self-assessment of the state of preparation of its infrastructure before inviting a mission from the agency” to prepare.[82] Chudakov stated that no such IAEA mission was scheduled for 2024 or 2025.[83] Burkina Faso and Russia signed an agreement to construct a nuclear power plant in October 2023 and have completed various preparatory phases since. Rosatom officials visited Ouagadougou in early August to discuss plans for building the power plant.[84]

Figure 8. Burkinabe-Russian Nuclear Cooperation

Source: Liam Karr.

Russian security assistance has not stopped the deteriorating security situation. Russia deployed 100 Africa Corps soldiers to Burkina Faso in January 2024 and eventually grew this number to between 200 and 300 troops.[85] Russian forces are primarily responsible for training, regime security measures, and protecting the junta leader Ibrahim Traore.[86] However, this support has not slowed the Salafi-jihadi insurgency in Burkina Faso. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has carried out several large-scale attacks in recent months, including two attacks in northern Burkina Faso since June that each killed hundreds of civilians and soldiers.[87] Russia also redeployed 100 soldiers from Burkina Faso to Ukraine in September, indicating they are unable or unwilling to scale up direct military support to address the deteriorating situation in Burkina Faso.[88]