The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaways:

Ethiopia. Amhara ethno-nationalist militias known as Fano have waged an offensive in northern Ethiopia’s Amhara region since July that has involved militants expanding control over several key roadways and included an attack on Ethiopia’s second-largest city in September. The offensive likely aims to establish control over key lines of communication to degrade the federal government’s access to northern Amhara and disputed territories in Tigray region. The Ethiopian government is likely unable to defeat the insurgency militarily, but Fano’s decentralized structure makes it hard for it to leverage its strength into political power. A strengthened Fano insurgency increases the risk of ethnic conflict with neighboring regions in Ethiopia, such as Tigray and Oromia, and would affect transnational issues involving Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan that could further destabilize Ethiopia or other areas in the Horn of Africa.

Somalia. Egypt sent its second major shipment of arms to Somalia, which will likely further escalate tensions with Ethiopia and increase the risk of a direct or proxy conflict. The influx of weapons to Somalia also risks accidentally arming al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab.

Mali. Tuareg separatist rebels have begun using drones to drop explosives on security forces for the first time. The new tactic will grant the group indirect fire capabilities that it can use to harass or fix security force units. The rebels’ contacts in al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate could have supported the group to develop this capability. Ukrainian officials have also claimed to support the rebels, although Ukraine has denied these isolated claims.

Burkina Faso. The Burkinabe junta claimed to thwart another coup, which it is using to rally populist support after several large-scale insurgency massacres of civilians.

Assessments:

Ethiopia

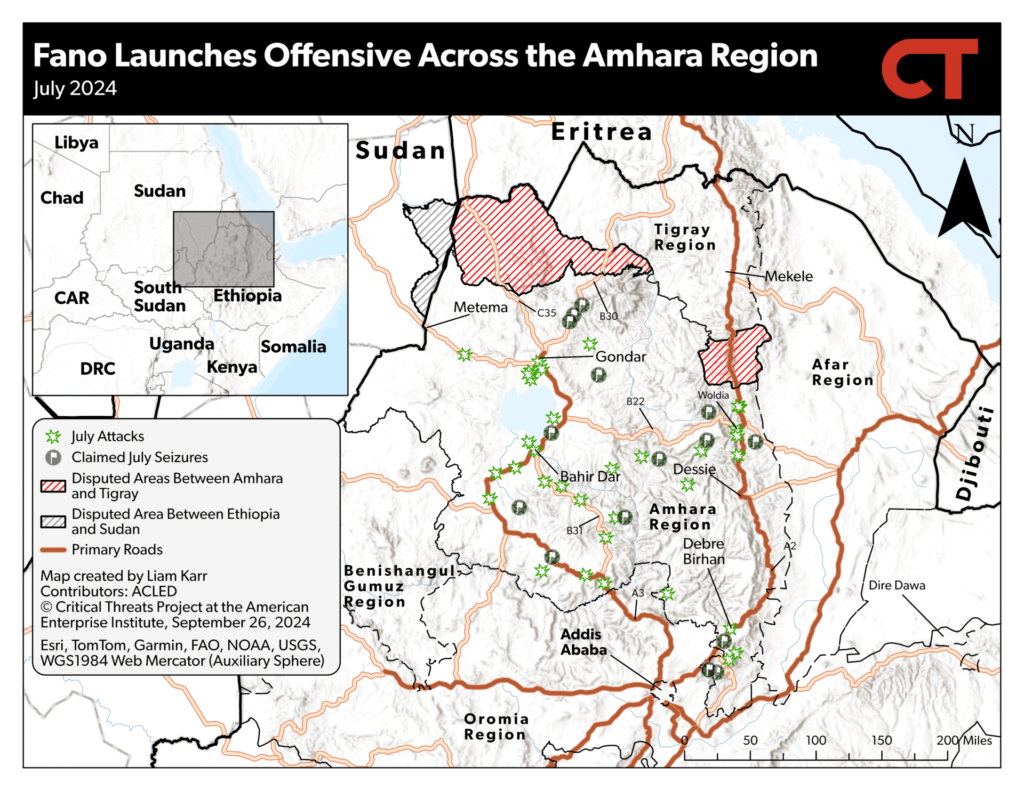

Fano has launched an offensive in northern Ethiopia’s Amhara region since July that has involved the militants’ briefly seizing several key areas, including parts of Ethiopia’s second-largest city in September. Fano is a wide range of loosely aligned, decentralized Amhara militias, most of which are small and operate autonomously.[1] These forces are highly effective despite their small size because they are well trained, as many members—including leadership—are former members of regional or federal armed forces and have extensive local support.[2]

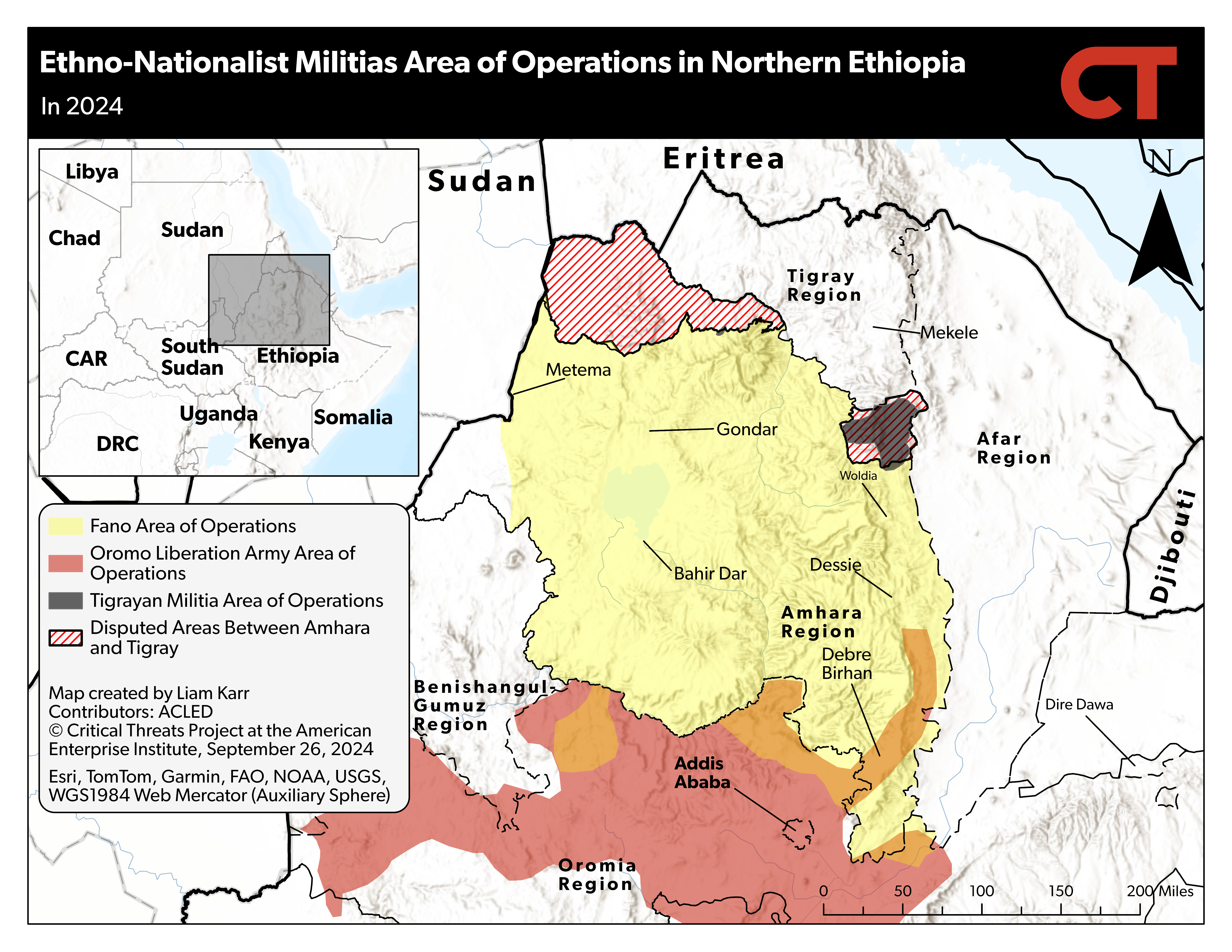

Figure 1. Fano Launches Offensive Across the Amhara Region

Note: Attacks are only Fano attacks against ENDF. Prior average is the monthly average from September 2023 to June 2024.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Fano factions have significantly increased their rate of attack on the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) across Amhara region since the beginning of July. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data project (ACLED) recorded that Fano carried out 68 attacks against the ENDF in Amhara region in each of July and August, and ACLED and CTP data show Fano is on pace to reach around this same number in September.[3] This rate is nearly triple Fano’s monthly average of roughly 25 attacks between September 2023 and June 2024.[4]

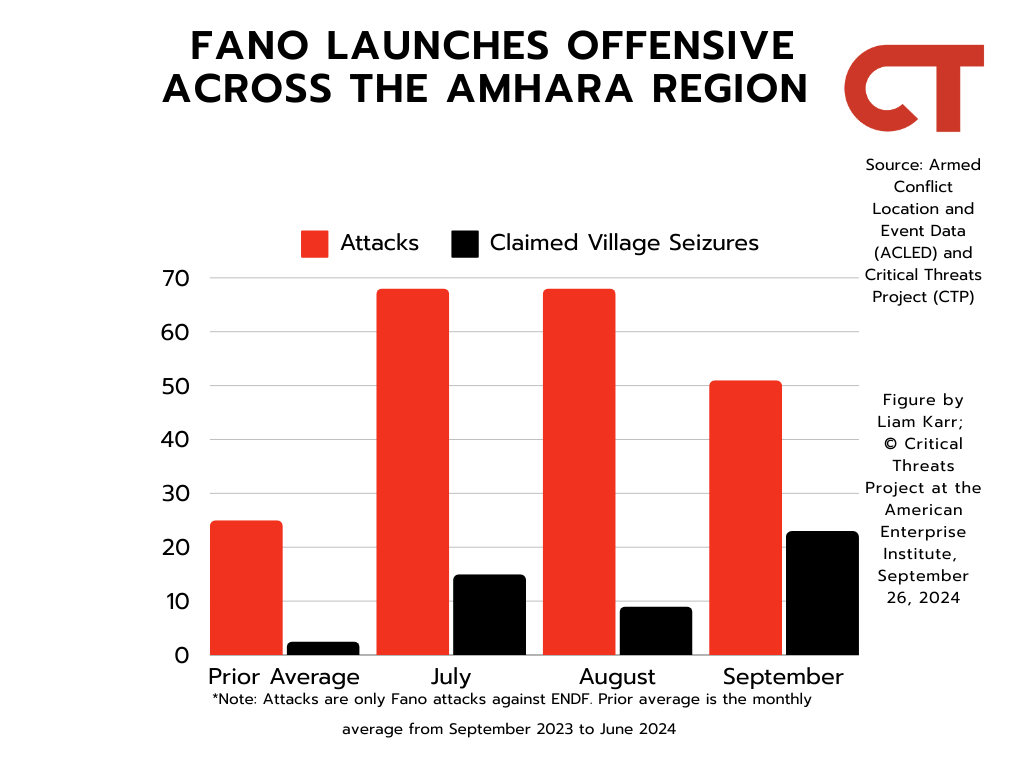

Figure 2. Fano Escalates Attacks Across the Amhara Region

Note: Attacks are only Fano attacks against ENDF in Amhara Region. “CAR” is Central African Republic and “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

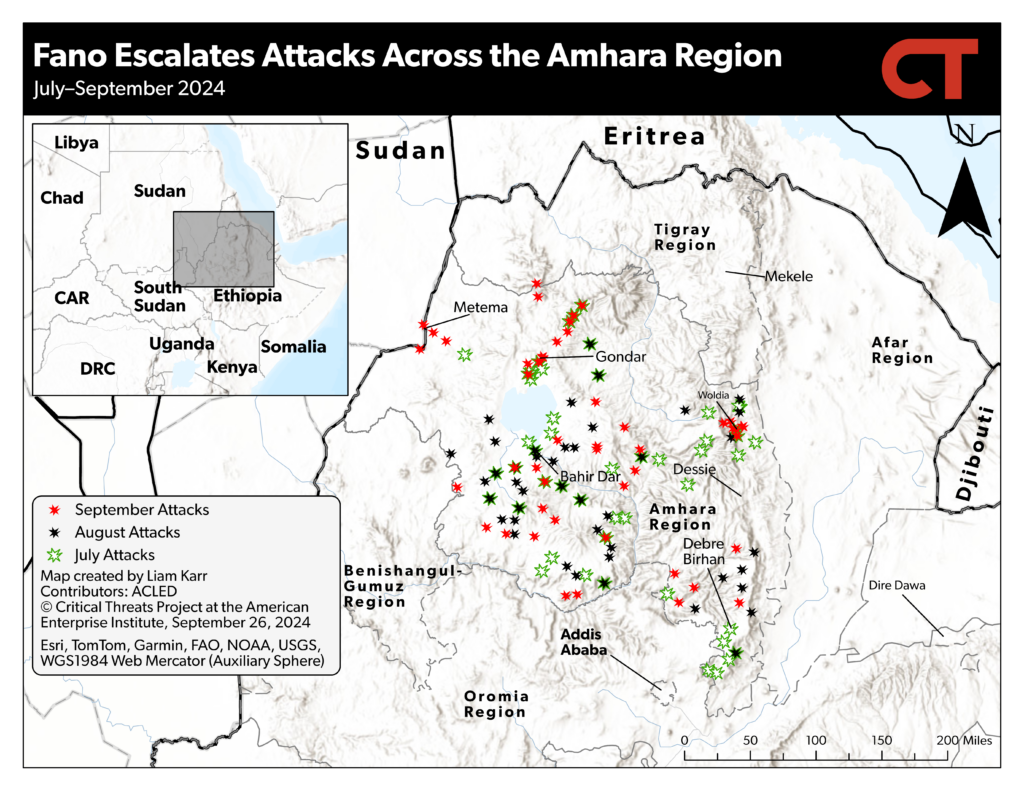

Fano has also claimed to briefly capture significantly more villages or rural districts, called woredas, during the offensive. ACLED recorded 15 Fano-claimed captures in July, nine in August, and another four in September.[5] CTP has recorded a further 19 claimed captures in September from Amhara-affiliated media sources, although it cannot confirm these claims.[6] These figures are exponentially larger than the monthly average of two to three villages from September 2023 to June 2024.[7] Fano also claimed to hold local elections to set up local administrations in seized areas, creating mechanisms to maintain its influence even though government forces often reenter most areas when Fano withdraws after the brief seizures.[8]

Figure 3. Fano Briefly Seizes Areas Across the Amhara Region

Note: “CAR” is Central African Republic and “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Fano attacked Gondar, Ethiopia’s second-largest city, on September 16.[9] Militants briefly controlled the southern part of the city before withdrawing to defense positions within 10 kilometers of the town.[10] It was Fano’s first significant assault on Gondar since it briefly seized the city during its first major offensive in August 2023.[11]

The Fano insurgency initially began in April 2023 after more than a year of deteriorating Fano ties with the federal government over grievances with the federal government’s protection of Amharas and Fano interests in various violent conflicts across Ethiopia. Fano initially began as a protest movement against the former Tigray-dominated federal government in 2016.[12] The movement adopted a more ethno-nationalist and militant approach in 2018 after the new Abiy-led government released many Amhara nationalist leaders from prison.[13] These leaders established ties to local militias and began recruiting ethno-nationalist fighters and former Ethiopia National Defense Force (ENDF) soldiers into paramilitary units that are now collectively known as Fano.[14] The militants organized to protect and advance Amhara ethno-nationalist interests, including land disputes and defending Amhara minorities facing violence in parts of Ethiopia outside Amhara region.[15]

Fano militants initially fought alongside the federal government during the Tigray war from 2020 to 2022.[16] Fano supported the federal government largely due to their shared enemy in the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).[17] Fano had been part of the political coalition that ousted the previous TPLF-led federal administration. The conflict was also a chance for Fano to assert its control over disputed areas of Tigray region that are de jure part of Tigray region but contain ethnic Amhara who want to be part of Amhara region.[18]

The partnership between Fano and the government fractured in 2022 as the Tigray war ended and tensions between the two surfaced.[19] The federal government views Fano as a threat because it is an unincorporated force outside government control.[20] Fano also had several issues with the Pretoria peace agreement that ended the Tigray war in November 2022. Fano was concerned that the federal government planned to force it to return control of the disputed areas it had captured during the civil war.[21] The government has since proposed a referendum in the disputed areas in line with the language of the Pretoria peace deal, but most Amharas oppose the idea.[22] Amharas also believe the peace deal fails to achieve accountability and justice for TPLF abuses against Amhara civilians during the war.[23] Amharas viewed the deal as a betrayal due to the popular perception that the federal government failed to protect Amhara when the TPLF invaded in 2021 and 2022, leaving Fano as the only line of defense.[24]

The schism between Fano and the federal government turned violent in April 2023 after the federal government moved to dissolve regional special forces across Ethiopia.[25] Fano and Amhara nationalists had already accused Abiy—an ethnic Oromo—and his government of failing to protect ethnic Amharas from ethnically motivated violence in the Beshangul-Gumuz and Oromia region and secure justice for the TPLF abuses.[26] This popular lack of trust in Abiy’s government contributed to many Amharas viewing the decisions to disarm Fano in 2022 and dissolve the regional special forces in 2023 as moves that aimed to leave Amharas defenseless.[27] The announcement triggered demonstrations and armed clashes between some Amhara regional special forces fighting alongside Fano militias against the Ethiopian federal government.[28] The ENDF forces took control of Amhara region, arrested Fano members and supporters, and disbanded the regional special forces, leading clashes to decline in May and June 2023.[29]

Fano regrouped, organized, and launched an offensive against several key cities in Amhara region in July and August 2023.[30] The federal government estimates that at least 50 percent of the disbanded special forces joined Fano, which was key to Fano’s strengthening.[31] Fano fighters attacked and briefly captured key cities, including the regional capital Bahir Dar, Gondar, and Lalibela.[32] Federal forces retook the towns, but the offensive undermined the federal government’s legitimacy by demonstrating that the group could inflict serious costs on federal forces and significantly disrupt civilian life.[33] Amhara regional council established a new government, including a new president and security sector heads, to try and address grievances in August 2023, but Fano and Amhara nationalists have continued to have little faith in the government and accused it of being dominated by Oromos.[34]

The recent Fano offensive likely aims to establish control over key lines of communication to degrade the federal government’s access to northern Amhara and disputed territories in Tigray region. The offensive began in July with operationally distinct Fano militias in Gondar and Gojjam provinces (known as zones in Ethiopia) increasing the rate of attacks along key roads.[35] ACLED recorded that Fano carried out ten attacks on the A3 road, which links the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa to Amhara regional capital Bahir Dar.[36] Militants carried out seven attacks along the B30 highway between the Gondar suburbs and the disputed regions in Tigray.[37] This included three temporary seizures of villages along the B30.[38]

Figure 4. Fano Launches Offensive Across the Amhara Region

Note: “CAR” is Central African Republic and “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Fano militants in Gojjam province escalated their efforts to degrade the lines of communication between Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar in August. ACLED recorded another 13 Fano attacks against ENDF forces along the A3.[39] Militants also expanded attacks to the neighboring B31 road, the other major road linking Addis Ababa and Bahir Dar, carrying out 12 attacks along the B31.[40]

Fano units in Gondar increased attacks on the B30 in September after a lull in August and launched an offensive to gain control over the C34 road, which links Amhara to neighboring Sudan. Fano carried out another eight attacks along the B30, this time claiming to briefly seize four villages, including two villages it previously claimed to capture in July.[41] Fano militants carried out ten attacks along the C34 and overran ENDF forces at Metema at the beginning of September, which Sudanese media reported led ENDF forces to withdraw and surrender to Sudanese forces across the border.[42] Controlling the crossing allows Fano to regulate and tax goods and people moving across the border from Sudan into Amhara region.[43]

Fano militias have regularly attacked and encircled Gondar city and Woldia town since July, likely to isolate government forces and establish control over smaller villages and rural areas along nearby roads. Fano’s voluntary withdrawal to encircle Gondar city and encirclement of Woldia highlights an attempt to isolate government forces in these larger population centers rather than establish lasting territorial control.[44] Fano has rarely controlled major urban centers since the insurgency began, and for only limited amounts of time, and this pattern repeated itself in Fano’s latest Gondar city attack.

Gondar and Woldia are key nodes in Amhara’s road system, with at least three major roads running through or near both towns. Gondar lies on the A3, B30, and C35, which all run north–south and link Addis Ababa, Amhara, and the western half of Tigray. It also links the east–west C35, which connects Amhara to Sudan. Woldia is on the A2, which runs north–south from Addis Ababa to southern Tigray via Amhara, and is the eastern endpoint of the B22, which connects eastern and Western Amhara and the A2 and A3 highways. Fano seized villages and district seats in more rural areas along the respective roads with government forces preoccupied with the threat to the major population centers.[45] These claims include numerous seizures on the B22, B30, and C34.[46]

The Ethiopian government is likely unable to defeat the insurgency militarily, and the latest offensive threatens to further erode the local trust and legitimacy of the federal government. The Ethiopian government has taken a military-centric approach to the insurgency by declaring a state of emergency, which establishes a command post from which a specially appointed federal representative reports directly to the prime minister.[47] The representative exercises broad powers, including the ability to detain suspects and search property without a court order, declare curfews, restrict group movements, and ban public gatherings.[48] The latest offensive highlights that these efforts have not degraded the insurgency.[49] Fano also claimed to set up local administrations in captured areas during the September 2024 offensive, creating mechanisms to maintain its influence even if government forces reenter these areas.[50]

The growing insurgency and violence against civilians threaten to further undermine popular support for the government in Amhara.[51] The general insecurity has contributed to the proliferation of criminal behavior such as kidnapping for ransom and civilian targeting.[52] This has led to protests against the federal government over the degradation of security.[53] Recent protests in Gondar city in September turned violent after security forces fired on protestors, killing at least 25 people and further feeding the popular grievances that are propelling the Fano insurgency.[54]

However, Fano’s decentralized structure makes it hard for the movement to leverage its strength into political power. Fano lacks a leader or unified platform for negotiations with the government, and the various factions that compose Fano have different strategic aims. Fano militias are also disunited and have varying goals due to their political, religious, and birthplace differences.[55] Fano factions’ goals range greatly, including some segments that want to overthrow Abiy’s government.[56] Fano has tried to organize to help facilitate peace talks, but internal fissures and a lack of trust in the federal government have hampered the discussions and prevented it from articulating a clear plan or positioning itself as a viable alternative to the federal government.[57] Fano commanders have personally stated that they are not ready to negotiate with the government before unifying themselves.[58] The federal government created a 15-member peace council in June to facilitate negotiations that has not made significant progress, but the head of the council said on September 25 that some leaders had shown an interest in discussions.[59]

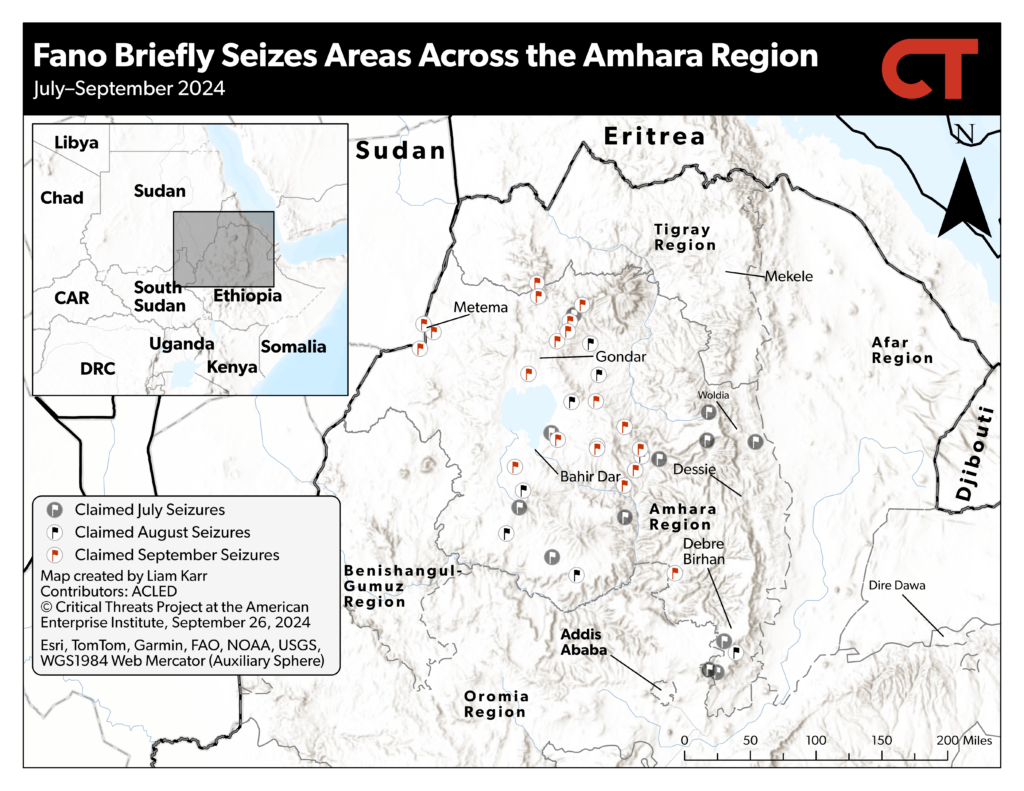

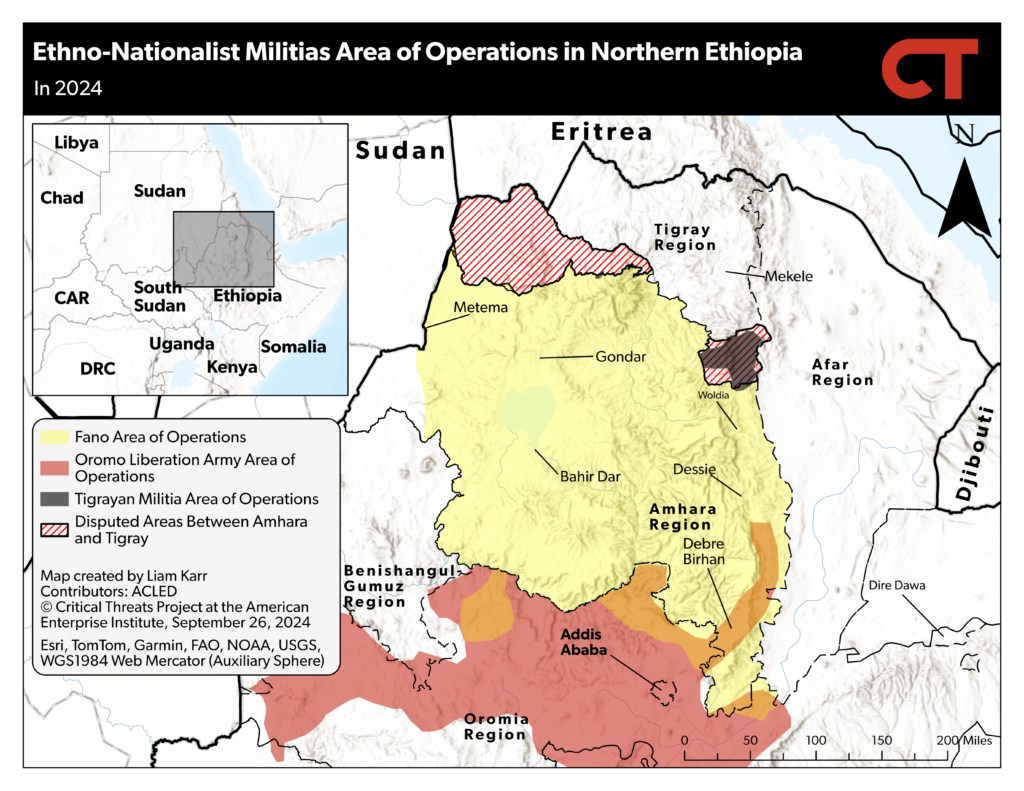

A strengthened Fano insurgency increases the risk of ethnic conflict with neighboring regions in Ethiopia, such as Tigray or Oromia. Fano’s effort to degrade government control of the lines of communication connecting Addis Ababa to the disputed areas of Tigray region during its recent offensive may be setting conditions to prevent political or military efforts to remove the territories from Amhara control, which would increase ethnic conflict between Amharas and Tigrayans. Tigrayan militia forces mobilized in February 2024 to retake the disputed areas under the de facto control of the Amhara administration, leading to several clashes with Fano.[60] The Tigray administration has also demanded that all non-Tigrayan forces withdraw from the disputed areas before a potential referendum, while the current Amhara administrations have rejected referenda outright.[61] The Tigrayan administration claimed in May that it reached an agreement with the federal government to return the thousands of displaced Tigrayans to the disputed areas, disarm combatants in the area, and create new local administrations.[62] Fano commanders called the announcement a provocation and accused the Tigrayan administration of “beating a war drum,” threatening to respond to any “invasion.”[63]

Figure 5. Ethno-Nationalist Militias Area of Operations in Northern Ethiopia

Note: “CAR” is Central African Republic and “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

add note

tweet

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Heavy-handed counterinsurgency measures could also further increase political tensions and violence between various segments of the Amhara and Oromo communities. Tension between the Amhara and Oromo regions has significantly grown since Abiy took office in 2018 on the back of a coordinated alliance between Amhara and Oromo opposition. Anti-Amhara pogroms in Oromia region and insurgent attacks against Amhara civilians by the insurgent Oromo Liberation Army have stoked anti-Oromo resentment in the Amhara community.[64] Fano has also forcibly territory in the Oromo region, which has led to several battles with regional security forces and attacks on Oromo civilians that have increased anti-Amhara resentment among the Oromo community.[65] The growing grievances have led to a split within the Amhara and Oromo factions of the ruling government as elites in the regional governments regularly contest each other’s narratives, reflecting the popular polarization to maintain the legitimacy of the factions.[66] Abiy leading a destructive counterinsurgency campaign would further inflame popular grievances that Abiy’s government is anti-Amhara and increase the potential of deadly ethnically motivated violence or fighting between Amhara militias and federal forces with Oromo militia support.[67]

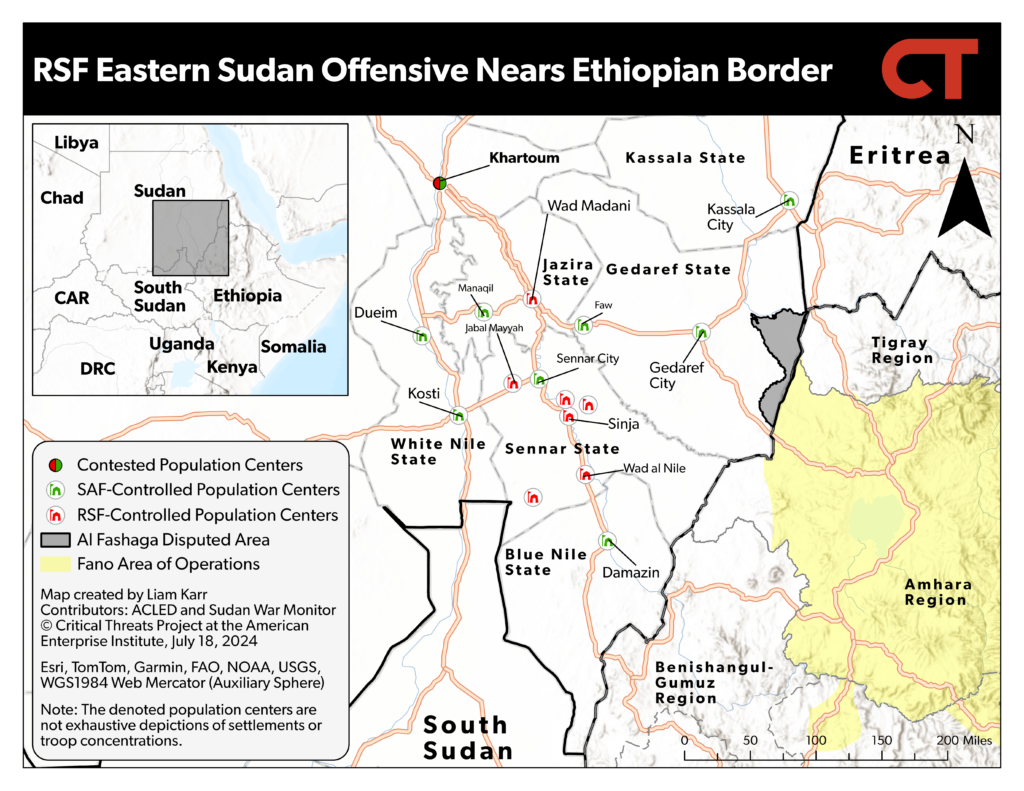

A stronger Fano insurgency or greater ethnic violence in Ethiopia would affect transnational issues involving Eritrea, Somalia, and Sudan that could further destabilize Ethiopia or other areas in the Horn of Africa. Greater insecurity in Ethiopia risks exacerbating refugee crises and ethnic violence in war-torn Sudan. Ethiopian officials have privately noted their concern that Fano could use its presence along the Sudanese border to establish ties with the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF).[68] Officials aired these concerns around the time Abiy met with the opposing Sudanese Armed Forces head in Sudan in early July 2024, shortly after the RSF established a presence near the Ethiopian border with an offensive in June 2024.[69]

Figure 6. RSF Eastern Sudan Offensive Nears Ethiopian Border

Note: The denoted population centers are not exhaustive depictions of settlements or troop concentrations. “CAR” is Central African Republic and “DRC” is Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Sudan War Monitor; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Fano and the RSF have mutual enemies inside Ethiopia and Sudan. The RSF is fighting the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), which Fano has fought several times since 2020 after the SAF evicted thousands of mostly Amhara fighters when it took control of the disputed al Fashaga border zone during the Tigray war.[70] The RSF has also made unsupported claims that Tigray militants are fighting alongside the SAF in Sudan, creating another mutual enemy with Fano.[71] CTP previously assessed that Fano and RSF coordination or cooperation would lead to an increase in illicit weapons flows and ethnic violence against Tigrayan refugees in Sudan and possibly Ethiopia.[72]

High tensions between Eritrea and Ethiopia could also lead Eritrea to support a strengthened Fano as a proxy. Eritrea already has ties with Fano dating back to the Tigray war, when it trained Fano militants to degrade the TPLF in the disputed areas of western Tigray that border Eritrea.[73] Fano’s efforts to keep the disputed areas under Amhara control with its recent threats and offensive on the roads linking Addis to western Tigray would keep lines of communication between Fano and Eritrea open in the event of a conflict. Continued Amhara administrative control of these disputed areas would hinder government efforts to uproot Fano from the area and cut its access to the C35 road, which connects Eritrea and western Tigray.

Eritrea had fought alongside the federal government against the TPLF, but tensions between the two former partners have grown substantially since the end of the Tigray war. Eritrea, much like Fano, viewed the Pretoria agreement negatively because it left the TPLF intact despite Eritrea’s desire to destroy the group.[74] Eritrea kept forces in Ethiopia for months after the 2022 peace deal due to concerns that the TPLF still constituted a national security threat, which was amplified by the increased alignment between the TPLF and the Ethiopian federal government following the peace deal.[75] Abiy also made inflammatory claims in 2023 that Ethiopia has a right to sea access, and that it could secure these rights through deals with Eritrea to the Eritrean ports of Assab or Massawa.[76] Abiy said that regaining Red Sea access, which it lost when Eritrea became independent in 1993, was an existential issue and “natural right” that Ethiopia would fight for if it could not secure it through peaceful means.[77] The two sides began mobilizing troops along their border in November 2023, increasing the risk of a clash.[78]

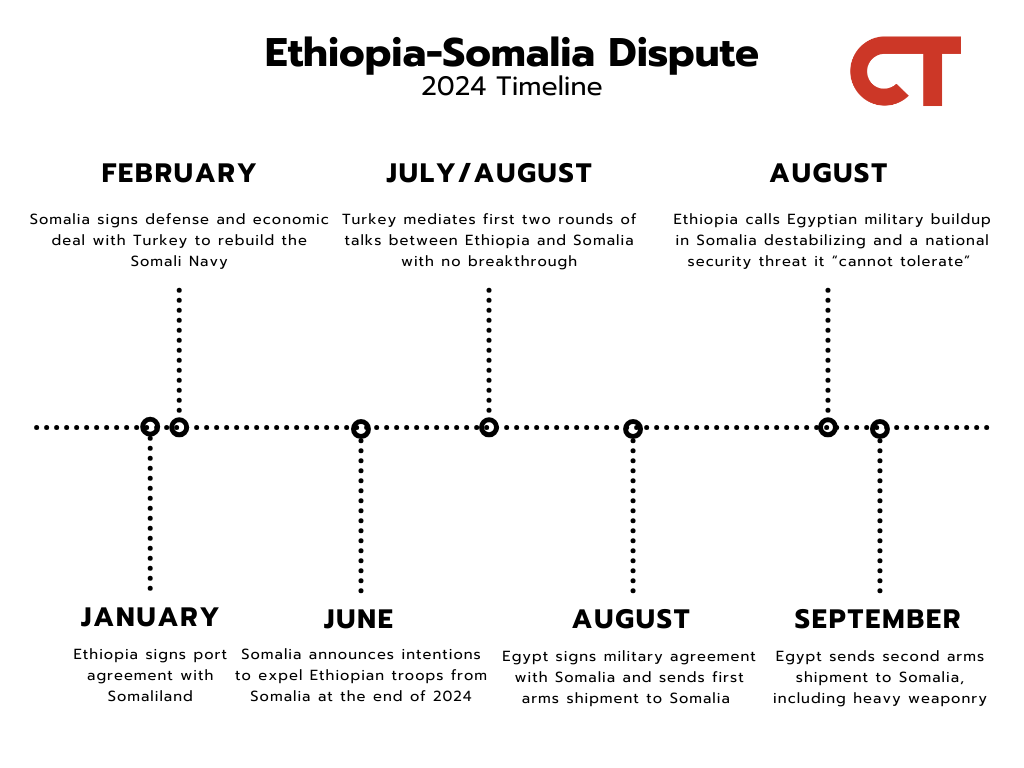

Greater internal conflict will also constrain Ethiopia’s ability to respond to Somalia and its ally Egypt, who are in a standoff with Ethiopia over Ethiopia’s decision to pursue Red Sea access through a deal with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding on January 1 with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region in northern Somalia that will give Ethiopia a lease of land for a port or naval base along Somaliland’s coast in exchange for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[79] The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty and turned to Egypt and Turkey to help counter Ethiopia’s move.[80] Egypt has seized the opportunity to advance its preexisting efforts to counter Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam project, which it has repeatedly labeled as an existential threat that will degrade—or enable Ethiopia to control—its Nile water supply.[81]

Figure 7. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

Ethiopia has labeled Egypt’s growing military presence in Somalia and Somalia’s threats to support ethno-nationalist movements—like Fano—as security threats and threatened to retaliate.[82] Egyptian media said Egypt deployed 1,000 soldiers to Mogadishu between August 27 and 29, while international media has reported on two arms shipments including ammunition, arms, artillery, and other weaponry since August.[83] Somalia also intends to replace Ethiopian forces fighting al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab with Egyptian forces, threatening to erode the buffer zone Ethiopia has created in Somalia to protect itself against al Shabaab attacks.[84] The Somali foreign minister said in mid-September that the SFG would consider establishing contact with rebels in Ethiopia if it followed through on its port agreement. CTP has assessed that currently dormant Somali insurgents in eastern Ethiopia would be the most practical option due to its proximity to Somalia rather than Fano.[85]

Ethiopia could redeploy some troops from its front with Somalia if the Fano insurgency significantly escalates, although CTP continues to assess that it is unlikely to withdraw from Somalia entirely despite the SFG’s plans to replace Ethiopian forces fighting al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab with Egyptian forces.[86] Bloomberg reported in 2020 that Ethiopia redeployed up to 3,000 soldiers from Somalia to Tigray during the Tigray war.[87] However, it never withdrew from the African Union peacekeeping mission entirely. This drawdown may have contributed to al Shabaab making some initial breakthroughs during its first major offensive into Ethiopia in 2022, although the ENDF and state paramilitary police helped repel the attack.[88] The al Shabaab offensive highlighted Ethiopia’s need to maintain a buffer zone in Somalia to protect against such attacks. Ethiopia maintains more than 3,000 troops in Somalia as part of the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), and 5,000–7,000 additional Ethiopian soldiers are in the country on a bilateral basis across the regions of central and southern Somalia that border Ethiopia.[89] Local outlets have reported that Ethiopia began building up its military forces in Somali region in August and has seized several airports in regions of Somalia bordering Ethiopia in response to Egypt’s military buildup in Somalia.[90]

Somalia

Egypt sent its second major shipment of arms to Somalia, which will likely further escalate tensions with Ethiopia and increase the risk of a direct or proxy conflict. An Egyptian warship arrived in Mogadishu on September 22, carrying heavy weaponry that included antiaircraft guns and artillery.[91] Egypt sent its first shipment of arms and ammunition to Somalia in late August.[92]

Ethiopia said it was “deeply alarmed” by the shipment, and Egypt and Ethiopia have traded threats. The UK-based outlet al Araby al Jadid reported on September 24 that Ethiopia sent a backchannel message to Egypt via Djibouti that “any Egyptian military forces that harm Addis Ababa’s interests in Somalia will not be immune from dealing with them.”[93] Egypt reportedly responded that “it is ready to escalate and respond forcefully to any attempt to harm the Egyptian presence in Somalia or Somali interests, in implementation of the military protocol signed with Mogadishu.”[94]

Egypt and Somalia are intentionally framing their military cooperation to threaten Ethiopia while hedging that their cooperation will also help combat al Shabaab. Egypt’s foreign ministry spokesperson said the shipment aimed to support Somalia to “combat terrorism and preserve its sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity.”[95] The latter objective refers to Somalia’s efforts to counter Ethiopia’s port deal with Somaliland. CTP has previously noted that many of the arms Egypt has sent could be used against al Shabaab.[96] However, the arrival of heavy weaponry such as anti-tank and antiaircraft artillery is more clearly meant for use against Ethiopia, as al Shabaab lacks the capabilities to warrant such weaponry. Egyptian media also reported in early September that Egypt and Somalia were planning a military exercise, which CTP previously assessed as almost certainly anti-Ethiopian rather than anti-al Shabaab.[97]

CTP previously assessed that the rising tensions could lead to a direct war or proxy conflict that pits Ethiopia against Egypt and Somalia. You can read the full assessment of the dispute, each actor’s objectives, and forecasts in the latest Africa File Special Edition: “External Meddling for the Red Sea Exacerbates Conflicts in the Horn of Africa”: https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/africa-file-special-edition-external-meddling-for-the-red-sea-exacerbates-conflicts-in-the-horn-of-africa#Somalia.

The influx of weapons to Somalia also risks unintentionally arming al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab. Somaliland officials both warned that the weapons could fall into the hands of al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab.[98] Al Shabaab has previously looted SFG weapons and stockpiles when it overruns Somali National Army (SNA) bases or acquired weapons on the black market due to corruption within the SFG and SNA.[99] Somalia recently lifted a partial arms embargo to Somalia at the end of 2023 that had been in place in various forms for several decades due to these fears.[100]

Mali

Tuareg separatist rebels have begun using drones to drop explosives on security forces for the first time. The Tuareg rebel coalition Strategic Framework for the Defense of the People of Azawad (Cadre stratégique pour la défense du peuple de l’Azawad, or CSP-DPA) has used drones to drop explosives on security forces at least three times since August. They first debuted the tactic in their deadly ambush on Malian and Russian forces at Tinzaouten, which killed up to 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers.[101] The rebels then claimed an attack that involved a drone dropping mortars on a Malian army base in the Timbuktu region on September 11.[102] Local sources linked the CSP to a similar attack that targeted the Malian army base in Timbuktu city during Malian Independence Day celebrations on September 22 and another army base in the Timbuktu region on September 26.[103]

The new tactic enables the group to conduct indirect fire to harass or fix security force units. The CSP seems to lack mortar supplies. ACLED has only recorded one mortar attack from the CSP and its constituent groups since they resumed fighting the Malian government in August 2023.[104] This attack also could have been al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al Islam (JNIM), which regularly shells Malian army camps. The drone explosive tactics will help address this mortar gap. The tactic presumably contributed to the severity of the Tinzaouten ambush by helping halt and sandwich the convoy. The rebels are also still learning to use this new technology. For example, the CSP missed its target and dropped the payload outside of the Malian army camp during the September 11 attack.[105]

The CSP’s contacts in JNIM could have supported the group to develop this capability. ACLED first recorded JNIM using this same drone tactic in September 2023 in an attack on a militia base in central Mali. ACLED has since recorded seven similarly styled attacks in central Mali and Burkina Faso. The CSP has significant historical ties to JNIM dating back to the 1990s, and in recent years, they have made informal ceasefire agreements in their shared support areas, maintained significant areas of operation and membership overlap, and operationally coordinated against the Islamic State Sahel Province.[106] These ties and dueling claims led CTP and international media outlets to assess that militants from both groups participated in the Tinzaouten ambush, where the CSP claimed to first debut this tactic.[107]

However, the JNIM subgroup using these tactics in central Mali and Burkina Faso is different from the JNIM subgroup in northern Mali, which could inhibit tech transfers. The Macina Liberation Front (MLF) is the JNIM subgroup based in central Mali, while Ansar al Din is in northern Mali. The MLF and Ansar al Din are heavily connected, however. The MLF’s founder was a disciple of JNIM emir and Ansar al Din founder Iyad ag Ghali, many of its longtime members fought under Ansar al Din in the 2012 rebellion, and the group initially described itself as Ansar al Din’s “Fulani branch” in 2016, referring to its recruitment among the Fulani ethnic group.[108] Ansar al Din has not conducted any drone attacks similar to the CSP or MLF attacks despite these ties.

A Ukrainian official also claimed that Ukraine supported the CSP, but the Ukrainian government denied it. The spokesperson of Ukraine’s military intelligence branch said after the Tinzaouten that “the [non-jihadist] rebels received the necessary information, and not just information” to enable the successful attack.[109] The Ukrainian government has since denied these claims.[110] Ukraine has used drones to drop explosives like mortars and grenades on invading Russian forces.[111]

Burkina Faso

The Burkinabe junta claimed to thwart another coup, which it is using to rally populist support after several large-scale insurgency massacres of civilians. Burkinabe Security Minister Mahamadou Sana made a statement on state media on September 24 that the junta had thwarted a broad conspiracy to overthrow the junta.[112] Sana said the conspiracy involved previous junta leader Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, Western intelligence agencies, European mercenaries, and dissidents based in neighboring countries like Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria.[113] Sana said the plan involved a group of 150 militants that were to attack the presidential palace in Ouagadougou, and two other groups to attack key drone installations and border posts to preoccupy security forces.[114] The junta also framed a recent JNIM attack on August 2024 that killed hundreds of civilians as part of the plot and said that the attack aimed to destabilize the country to facilitate the coup.[115]

CTP has assessed in recent months that the Burkinabe junta faced a high coup risk due to several major Salafi-jihadi attacks. The most recent attack killed at least 100 villagers in northern Burkina Faso on August 24, with most sources citing death tolls of between 200 and 400 civilians.[116] JNIM militants killed nearly 200 Burkinabe soldiers and civilians during an ambush on a military convoy on August 9.[117] The junta had already survived a potential coup in June, which followed what had been the JNIM’s deadliest-ever attack on Burkinabe forces.[118] The junta also claimed to thwart a coup attempt in September 2023, several weeks after another major attack.[119] Large-scale insurgent attacks contributed to both successful coup attempts in Burkina Faso since 2022.