The Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.

Key Takeaway: Russia and several countries in the Middle East, including Iran, are taking advantage of conflicts that have emerged in Sudan and Somalia to grow military engagement with some of the factions involved in the crises. These countries are advancing their economic, military, and political objectives in the Horn of Africa and the greater Red Sea area at the expense of the interests of the local populations and the United States. Shifting regional alliances in the Middle East have shaped some of the external engagement in the Horn of Africa as powers compete for economic, military, and political influence in the Red Sea.

Sudan. Iran, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates are backing various sides in Sudan’s civil war to advance their interests in the region, complicating peace talks and exacerbating the violence and resulting humanitarian crisis. Iran and Russia in particular are providing military supplies in pursuit of Red Sea naval bases that would enable both countries to threaten US economic and military interests in the Red Sea.

Somalia. Somalia has turned to Egypt and Turkey to help counter a naval base agreement between Ethiopia and the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region in northern Somalia. Egypt and Turkey have benefited from this development to advance their own economic, military, and political objectives in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea. Their involvement has increased the risk of a broader regional conflict and prolonged the crisis to the detriment of US counterterrorism interests in Somalia and the local population.

Assessment:

External powers are taking advantage of conflicts that have emerged in the Horn of Africa to advance their economic, military, and political objectives in the Horn of Africa and the greater Red Sea area at the expense of the interests of the local populations and the United States. Sudan’s ongoing civil war has resulted in a growing humanitarian crisis since it began in 2023.[1] The United Arab Emirates (UAE) has given military aid to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) to protect its economic and political ties in Sudan.[2] Egypt, which is a historical military partner for the rival Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), has been unable or unwilling to provide decisive military support, leaving a vacuum for Iran and Russia to strengthen their ties with the SAF. Iran and Russia are giving military support to the SAF in pursuit of Red Sea naval bases, which would threaten the freedom of navigation that underpins US economic and military interests in the region.[3] External military aid has made the civil war deadlier and complicated peace efforts to the detriment of the Sudanese people.

Ethiopia and Somalia are also locked in a separate dispute over Ethiopia trying to secure Red Sea access through a deal with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Somalia first turned to Turkey to counter Ethiopia, creating opportunities for Turkey to advance its economic and political interests.[4] Turkey’s gains have come at the expense of the economic and political interests of the UAE, which is trying to grow influence in the Red Sea through client ports with allies such as Ethiopia and Somaliland.[5] Somalia has also increased cooperation with Egypt to counter Ethiopia, opening another avenue for Egypt to counter Ethiopia’s growing influence in the Nile and Red Sea.[6] Growing external military engagement with Somalia has increased the risk that the dispute between Ethiopia and Somalia could escalate into a direct or proxy armed conflict and exacerbated the conflict to the detriment of counterterrorism efforts against one of al Qaeda’s strongest affiliates, al Shabaab.

Shifting regional alliances in the Middle East have shaped some of the external engagement in the Horn of Africa as powers compete for economic, military, and political influence in the Red Sea. Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia were at the core of a de facto anti-Iran and anti-Islamist coalition during the late 2010s that aimed to contain Iran and its proxies and coerce countries such as Turkey and Qatar from supporting regional Islamist factions. The Gulf states and Iran supported opposing sides in the Syrian and Yemeni civil wars, and the rivalry eventually contributed to the UAE and Saudi Arabia cutting diplomatic ties with Iran in 2016 and supporting US policy to isolate and weaken Iran through a “maximum pressure” campaign in the late 2010s.[7] Egypt has a deep historical rivalry with Iran, and the two have lacked formal diplomatic ties since the Iranian revolution in 1979.

Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia also view Islamist movements as threats to their regimes, which put them at odds with Turkey’s pro-Islamist president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Turkey and the three Arab countries took opposing sides on many issues, including the post–Arab Spring Islamist governments, the Libyan civil war, and the trio’s efforts to blockade Qatar for its links to Islamist movements and Iran.[8] Turkey maintained a tense relationship with both Gulf states and cut diplomatic ties with Egypt between 2013 and 2021 due to Turkey’s condemnation of the coup that overthrew Egypt’s Islamist government and installed Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi.[9]

Competition between the Egypt–UAE–Saudi Arabia coalition and their Iranian and Turkish rivals over military and political influence in the Red Sea manifested in the Horn of Africa. Iran had a strong relationship with former Sudanese dictator Omar al Bashir for decades after Bashir took power in an Islamist-backed coup inspired by the Iranian revolution in 1989.[10] The UAE and Saudi Arabia heavily contributed to Bashir abandoning this relationship in 2015 after they lured him to join their anti-Iran coalition with significant economic investment.[11] The UAE and Saudi Arabia then used Sudanese forces from both the RSF and SAF as part of their coalition against the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the Yemeni civil war.[12] Egypt quickly developed ties with the SAF after Bashir’s fall, in 2019.[13] The UAE and Turkey have also been key partners for more than a decade in Somalia, where both countries view engagement as an opportunity to grow their economic spheres of influence and expand their military footprint around the Red Sea.[14]

The Egypt–UAE–Saudi Arabia coalition has fractured since 2019 in the face of their policy failures and COVID-19–era economic shocks. Middle East political experts say Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia partially pushed for a détente because their more confrontational approach failed.[15] For example, the coalition’s efforts failed to stop Iran’s Yemeni proxy—the Houthis—from becoming the dominant faction in Yemen and launching drone attacks targeting the UAE and Saudi Arabia.[16] Qatar also never implemented any of the 13 demands of the blockading coalition.[17] Economic shocks stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war also further pushed all countries to pursue regional de-escalation so they could give greater priority to strengthening and diversifying their economies.[18]

The fracturing of the Egypt–UAE–Saudi Arabia coalition and growing emphasis on economic power has changed how Middle East powers are interacting with each other as they continue to compete for influence in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea. The UAE and Saudi Arabia are competing for economic spheres of influence in Africa through mineral access and supply-chain infrastructure, such as client ports in the Horn of Africa.[19] This impact of these changing priorities is evident in Sudan, where the coalition is no longer holding the fragile government together and instead supporting opposite sides of the war to advance their own interests.[20] The split has created the space for Iran to reconnect with Sudan without the Emirati-Saudi pressure on Sudanese actors to distance themselves from Iran.[21] Egypt is also on the opposite side of the UAE on regional issues including Sudan and Ethiopia but still finds itself constrained by its own economic reliance on the UAE to support its ailing economy.[22] Egypt has simultaneously increased diplomatic and economic cooperation with Turkey, which has created space for collaboration on now-less contentious foreign policy issues in the Palestinian territories, Libya, and parts of sub-Saharan Africa.[23]

Sudan

Sudan’s civil war has resulted in a growing humanitarian crisis since 2023, with internationally backed peace talks floundering and neither side able to reach a decisive breakthrough. The paramilitary RSF and the SAF have been fighting across Sudan since April 2023 to secure control over the state. Both groups jointly ruled Sudan in a delicate and informal power-sharing structure since helping overthrow both Sudan’s former dictator Omar al Bashir, in 2019, and the subsequent civilian-led transitional government, in 2022.[24]

The resulting civil war has led to a humanitarian catastrophe. The fighting has left 25 million Sudanese civilians facing acute food insecurity, displaced more than 10.2 million people, and killed at least 150,000 people, according to UN and US estimates.[25] Both sides have committed human rights abuses against civilians, and numerous international organizations have accused the RSF of ethnic cleansing against non-Arab civilians in Sudan’s Darfur region, where the Janjaweed militias that eventually became the RSF committed similar genocidal crimes that killed 300,000 people in the same area in the early 2000s.[26] Multiple international peace efforts have failed, and neither side has achieved a decisive victory, despite some significant RSF breakthroughs in parts of Sudan.[27]

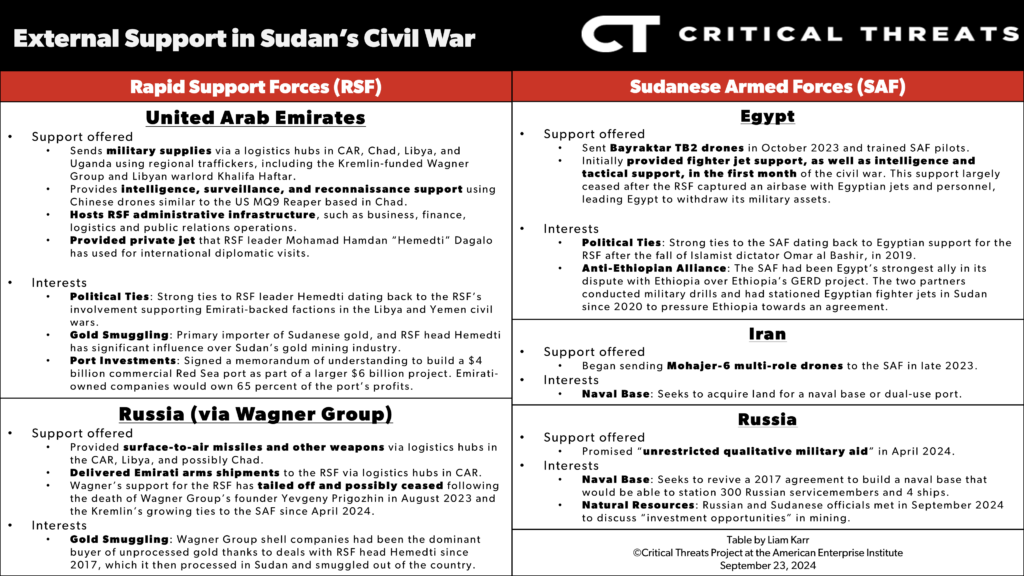

The UAE has backed the RSF to advance its economic and political objectives in Sudan and the Red Sea through its ties with the RSF leader, Mohamed Hamdan “Hemedti” Dagalo. The UN, United States, and other international observers have accused the UAE of funding and supplying the RSF with matériel via logistics nodes in neighboring countries such as the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Libya, and Uganda.[28] The New York Times reported in September 2024 that the UAE had recently begun using Chinese drones similar to the US MQ9 Reaper to provide intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support based in Chad.[29]

Hemedti and the RSF cultivated strong ties with the UAE via participation in the Emiratis’ military coalitions in Libya and Yemen that have since expanded into an economic partnership.[30] Hemedti’s influence over Sudan’s gold mining industry further makes him a crucial partner for the UAE, which is the leading importer of Sudanese gold.[31] These ties make Hemedti the UAE’s preferred partner to implement a $6 billion port and agriculture project on Sudan’s Red Sea coast that the UAE announced in 2022.[32] Emirati companies own a 65 percent stake in the planned port’s profits, and the project is part of the UAE’s strategy to grow economic and political influence and power via client ports along the Red Sea.[33]

Figure 1. External Support in the Sudanese Civil War

Source: Liam Karr.

Egypt—a historical military partner for the SAF—has been unable or unwilling to provide decisive military support, leaving a vacuum for Iran and Russia to strengthen their ties with the SAF in pursuit of Red Sea naval bases. Egypt’s poor economy and overstretched military have limited its ability to support the SAF. Multiple Africa-focused outlets and analysts reported that Egypt was considering entering the war more broadly in support of the SAF.[34] Egypt initially provided some fighter jet support, as well as intelligence and tactical support in the early days of the war.[35] However, the RSF attacked an SAF stationing Egyptian jets and pilots, causing Egypt to withdraw its assets and personnel from Sudan.[36] Egypt has seemingly not attempted to replace this support beyond a shipment of Turkish Bayraktar drones in October 2023 due to its nearly collapsed economy.[37] A $35 billion Emirati investment in February and billions more from the International Monetary Fund and EU have temporarily helped stave off the impending crisis, but the situation has greatly diminished Egyptian political capital and increased Egypt’s reliance on the RSF’s UAE backers.[38] Saudi Arabia has been a major economic partner for Sudan and has close political ties with the SAF but has never offered direct military aid.[39]

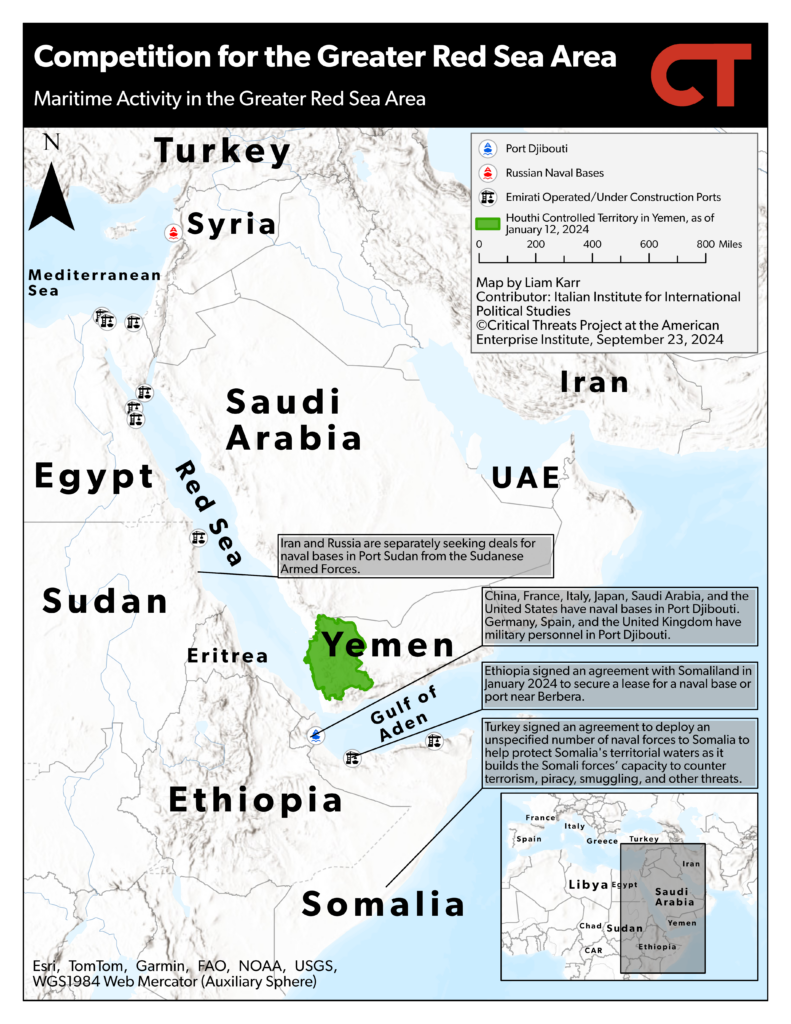

Iran and Russia have filled this vacuum by giving military aid to the SAF in pursuit of naval bases on Sudan’s Red Sea coast that would grow their power projection capabilities in the Red Sea. Iran restored diplomatic ties with the SAF-backed Sudanese government after a seven-year break in 2023, leading to several high-level meetings and the exchange of ambassadors in July 2024.[40] Iran also began sending Mohajer-6 multi-role drones to the SAF beginning in late 2023, which have helped the SAF in battles around the capital.[41] Iran has sought but failed to obtain an agreement for a naval base or dual-use port in Sudan in exchange for continued aid and a helicopter-carrying ship.[42] The SAF has rejected Iran’s overtures to avoid alienating its historical allies—Egypt and Saudi Arabia—as well as Western countries.[43]

The Kremlin increased its outreach to the SAF in 2024 to revive a dormant naval port agreement. Russia has been attempting for years to implement an agreement it signed with Bashir in 2017 to build a naval base in Sudan that would be able to station 300 Russian service members and four ships.[44] The Russian deputy foreign minister and special representative for the Russian president in Africa and the Middle East met with SAF Head Gen. Abdel Fattah al Burhan and other high-ranking officials in April 2024 and promised “unrestricted qualitative military aid” in exchange for the SAF—which controls Sudan’s coastline—implementing the 2017 deal.[45] The assistant SAF commander-in-chief claimed in late May that Sudan and Russia would soon sign a series of military and economic agreements to finalize the exchange.[46] However, Sudanese media reported in August that the sides are still finalizing aspects of the deal surrounding the conditions of the base and Russia providing fighter jets.[47]

Russia has pursued the naval port agreement despite its ties to the RSF via the Wagner Group. The Kremlin-funded Wagner Group worked with the RSF between 2017 and 2023 due to its business interests in Sudan’s gold mines and even armed the RSF following the outbreak of the civil war.[48] CTP and The Telegraph have noted that Wagner’s support for the RSF has likely tailed off and possibly ceased following the death of Wagner Group’s founder, Yevgeny Prigozhin, in August 2023 and the Kremlin’s growing ties to the SAF since April 2024.[49] Russia is also attempting to replace the gold smuggling arrangements it had with the RSF through mining deals with SAF after the civil war halted Wagner’s smuggling operation.[50]

Greater Iranian and Russian power projection in the Red Sea threatens freedom of navigation that underpins US economic and military interests. An Iranian naval base at Port Sudan would support Iran’s and its Axis of Resistance’s power projection and attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. A Russian naval base would enable the Kremlin to better challenge the West in the Red Sea and adjacent theaters such as the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean in the event of a broader conflict.

Figure 2. Competition for the Greater Red Sea Area

Source: Liam Karr.

External military support for both sides has intensified and prolonged the civil war to the detriment of Sudanese civilians. Outside support for the factions in Sudan makes the conflict more deadly for civilians and soldiers by introducing higher-end weapon systems, such as drones.[51] The continued provision of matériel enables both sides to continue fighting and carrying out their human rights abuses without proving decisive, complicating mediation efforts.[52] For example, Iranian drones have helped the SAF regain territory in the Sudanese capital while the SAF continues to suffer losses elsewhere, meaning the support is not decisive enough to win the SAF the war but it helps it avoid a decisive defeat and continue fighting for a more optimal outcome.[53]

Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia have been pushing for peace in Sudan. A halt to the conflict would help stabilize Egypt and Ethiopia’s borders with Sudan and protect Saudi Arabia’s significant economic investments in the country.[54] Egypt and Ethiopia have used their relationship with the UAE to encourage the Emiratis to push for peace.[55] Ethiopia has also used its ties with both Sudanese factions and Sudanese civil society to facilitate increased dialogue between Sudanese and external backers.[56] The growing pressure has led to more serious peace talks after a significant lull in the first half of 2024 following failed efforts throughout 2023.[57] However, both sides remain far from common ground on even basic issues, leading to no-shows or bad-faith participation in most discussions.[58] The external parties’ self-interests also jeopardize their ability to serve as impartial mediators.[59]

Somalia

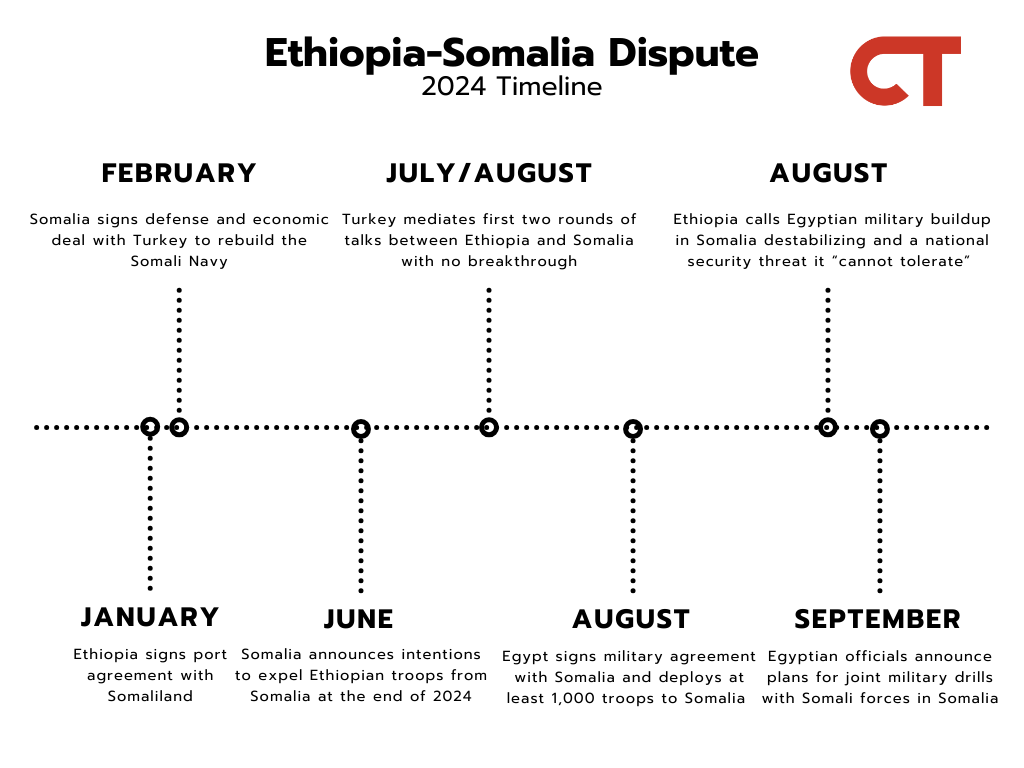

Ethiopia and Somalia are locked in a diplomatic dispute that is drawing involvement from external powers looking to strengthen their hand in the wider Red Sea theater, increasing the risk that the crisis escalates into a regional conflict. Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding on January 1 with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region in northern Somalia that will give Ethiopia a lease of land for a port or naval base along Somaliland’s coast in exchange for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[60] The port would give Ethiopia access to Red Sea shipping lanes via the Bab al Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen that connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed described Red Sea access in July and October 2023 as an existential issue and “natural right” that Ethiopia would fight for if it could not secure it through peaceful means.[61]

The Somali Federal Government (SFG) has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty. The SFG rejected the agreement on January 2 as “null and void” for violating Somali sovereignty and international law and threatened to “retaliate” if Ethiopia followed through.[62] The Somali cabinet labeled the Somaliland-Ethiopia memorandum a “blatant assault” on its sovereignty and said it was an example of Ethiopian “interference against the sovereignty of Somalia.”[63]

Figure 3. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute: 2024 Timeline

Source: Liam Karr.

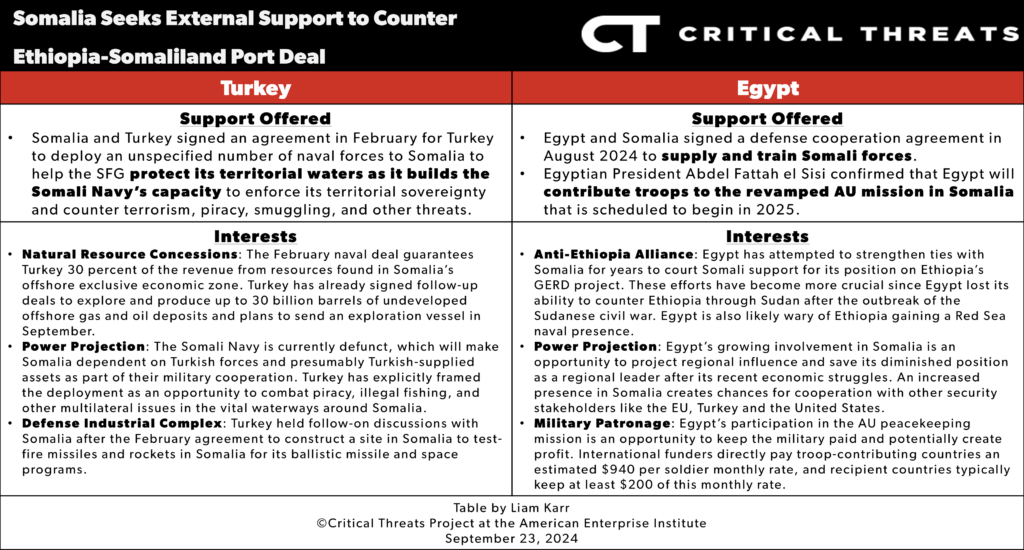

Somalia has turned to Turkey to counter the port deal, creating significant opportunities for Turkey to advance its economic, defense, and power projection interests in the wider Red Sea theater. Turkey and Somalia signed an economic and defense deal in February 2024 that increases its military presence in crucial waterways and gives it access to underdeveloped offshore oil reserves in exchange for reconstructing, equipping, and training the defunct Somali Navy.[64] CTP previously assessed that Somalia intends for the deal to counter or deter Ethiopia’s port deal despite the SFG officially denying the two are connected. The deal guarantees Turkey 30 percent of the revenue from resources found in Somalia’s offshore exclusive economic zone. This stake has significant potential if Turkey can develop Somalia’s “blue economy,” which refers to economic activities in the ocean and coastal areas, and offshore oil and gas extraction.[65] Turkey has already signed follow-up deals to explore and produce up to 30 billion barrels of undeveloped offshore gas and oil deposits and announced plans to send an exploration vessel in October.[66]

The agreement also boosts Turkey’s defense and general power projection aims in the Red Sea. Turkey will deploy an unspecified number of naval forces to Somalia to help the SFG protect its territorial waters as it builds the Somali forces’ capacity to counter terrorism, piracy, smuggling, and other threats.[67] Somali forces have minimal naval capabilities, which will make Somalia dependent on Turkish forces and presumably Turkish-supplied assets as part of the cooperation.[68] Turkey has already announced plans to send two warships to Somalia to protect its exploration vessel.[69] This situation will increase Turkish and pro-Turkish naval presence near critical waterways off the Somali coast, such as the Bab el Mandeb strait, enabling Turkey to increase its geopolitical influence in the broader Horn of Africa–Red Sea region.[70] Turkey has explicitly framed the deployment as an opportunity to combat piracy, illegal fishing, and other multilateral issues in the region.[71] Turkey has also held follow-on discussions with Somalia to construct a site in Somalia to test-fire missiles and rockets in Somalia for its ballistic missile and space programs.[72]

Turkey’s agreement with Somalia comes at the direct expense of the UAE’s economic and political interests in the Horn of Africa and the broader Red Sea area. The SFG had been considering a similar landmark deal with the UAE for over a year before it signed the 2024 deal with Turkey.[73] The SFG may have chosen Turkey over the UAE due to the UAE’s strong ties with Ethiopia and Somaliland. The UAE has invested nearly half a billion dollars in Somaliland’s Berbera port in exchange for a 30-year concession to manage the port.[74] The UAE has also invested billions of dollars in Ethiopia since 2018 and sent arms during the Tigray war from 2020 to 2022.[75] It began building an air base in Somaliland but voluntarily scrapped the project in favor of a civilian airport in 2019 when its diminishing role in the Yemeni civil war removed the need for the base.[76]

The Ethiopia-Somaliland agreement is also in UAE’s economic interests and aligned with its strategy to create more friendly client ports along the Red Sea. The UAE helping landlocked Ethiopia gain more access to the Red Sea and establishing another potential client port would reap significant benefits for the UAE given Ethiopia’s economic and political importance in Africa. Ethiopia is Africa’s fifth-largest economy. The Emiratis already sought to get Ethiopia partial ownership in the Berbera port in 2019, but Ethiopia failed to make the necessary payments on time.[77]

Figure 4. Somalia Seeks External Support to Counter Ethiopia-Somaliland Port Deal

Source: Liam Karr

Somalia has also increased military cooperation with Egypt to deter Ethiopia from following through on its port deal with Somaliland. This has created an opportunity for Egypt to advance its preexisting efforts to counter Ethiopia’s growing influence in the vital Nile and Red Sea. Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud has visited Cairo twice in 2024, following strong and outspoken Egyptian support for the SFG’s position on the Ethiopia deal.[78] Egypt and Somalia signed a defense cooperation agreement during Mohamud’s most recent visit, in August, and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el Sisi confirmed that Egypt will contribute troops to the revamped African Union (AU) mission in Somalia that is scheduled to begin in 2025.[79] International media reported that 5,000 Egyptian troops will deploy to Somalia around Mogadishu as part of the mission, while Egyptian media said the deployment could be as many as 10,000.[80]

Egypt recently deployed troops to Somalia as part of this new cooperation. Egypt sent 1,000 soldiers and arms and ammunition to Mogadishu between August 27 and 29.[81] Egyptian officials said Egypt would ship armored vehicles, rocket launchers, artillery, anti-tank missiles, radars, and drones as part of the defense deal. Egypt and Somalia are also planning to hold joint military exercises in Somalia sometime in September.[82] Egyptian officials said the exercise will involve ground, air, and naval forces and “send a clear and loud message about our firm commitment to co-operate and protect Somalia.”[83]

Egypt has attempted to strengthen ties with Somalia for years to court Somali support for its position on Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project.[84] Egypt has repeatedly labeled the GERD an existential threat that will degrade—or enable Ethiopia to control—its Nile water supply and argued that Ethiopia should not fill the GERD without a legally binding agreement that resolves concerns about the dam’s downstream effects.[85] The Nile is vital for Egypt’s economy and general population given that it gets 90 percent of all its water from the Nile, which it uses for electric production, agriculture, and drinking water.[86]

These efforts have become more vital since Egypt lost its ability to counter Ethiopia through Sudan after the outbreak of the Sudanese civil war.[87] The SAF had backed Egypt’s stance on the GERD as Sudan is another downstream Nile country, and the two had engaged in military drills and stationed Egyptian fighter jets in Sudan since 2020 to pressure Ethiopia towards an agreement.[88] However, the Sudanese civil war has preoccupied the SAF and nullified Egypt’s military capacity in Sudan after Egypt withdrew from Sudan following an RSF attack that hit its Sudan-based assets in the early days of the war.

Egypt also likely wants to deny Ethiopia Red Sea naval access, which would create opportunities for Ethiopia to threaten Egypt’s Red Sea rents in the far future. Egypt received roughly $9 billion annually from Suez Canal receipts before the Israel-Hamas war in Gaza, which began in October, and the subsequent Houthi campaign in the Red Sea.[89] The Houthi attacks have more than halved this figure in 2024.[90] Ethiopia signed defense accords with France to reestablish its defunct navy in 2019 but has not made notable progress since.[91]

Egypt’s engagement with Somalia also creates opportunities for Sisi to rebuild international and domestic prestige. Egypt’s growing military cooperation with Somalia may signal a renewed Egyptian effort to project regional influence and save its diminished position as a regional leader after its recent economic bailout. Egypt has faced a stagnating economy and resulting economic crunch in recent years that the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas war have exacerbated, leading to inflation, rising poverty rates, and significant foreign debt.[92] The crisis depleted Egypt’s political capital and contributed to Egypt being unable to project decisive power outside of its borders, including places like Sudan.[93] However, more than $50 billion of investment—equal to 10 percent of Egypt’s total gross domestic product—from the EU, International Monetary Fund, and UAE in early 2024 has presumably alleviated Sisi’s economic concerns and created more bandwidth for more assertive foreign policy.[94] Using this bandwidth to increase its role in Somalia helps restore Egypt’s prestige as a regional military power and creates opportunities for cooperation with Somalia’s other security stakeholders, including the EU, Turkey, and the United States.

Egypt’s participation in the AU peacekeeping mission will also help Sisi domestically by helping fund his vital military powerbase and potentially create profit. International funders directly pay troop-contributing countries an estimated $940 per soldier each month.[95] The contributing governments typically keep at least $200 of the per-soldier monthly rate for administrative uses, such as uniforms and training, and give the remaining amount to soldiers. For reference, Kenya received $48 million in funding in fiscal year 2023.[96]

Egypt’s military buildup in Somalia is heightening tensions and growing the risk of a regional conflict. The timing and nature of Egypt and Somalia’s recent military cooperation indicate that the collaboration is not tied purely to the mandate of the AU peacekeeping mission and is meant to threaten Ethiopia. Egyptian troops have arrived months before the planned AU transition at the end of 2024. Furthermore, the AU and UN will not finalize the new mission’s funding, concept of operations, and other troop-contributing countries until October.[97] This timing discrepancy indicates that the soldiers are not primarily there as part of the planned peacekeeping mission. The anti-tank missiles Egypt plans to send are also more geared for a conventional conflict, as al Shabaab does not use sophisticated enough vehicles to require anti-tank weapons.

Plans for an Egypt-Somalia military exercise further underscore the partnership’s anti-Ethiopian intentions. Egyptian officials announced a future military exercise with Somalia one day after their September 1 warning about Ethiopia’s GERD activity.[98] Egypt previously used military exercises with Sudan to pressure Ethiopia on GERD negotiations.[99] Egyptian officials also said the exercise aims to “send a clear and loud message about our firm commitment to co-operate and protect Somalia.”[100] This framing is consistent with Egypt’s previous promises to protect Somali sovereignty from Ethiopia throughout 2024, indicating that the exercises are a message to Ethiopia and not counterinsurgency operations.[101] Military exercises in regions of Somalia that border Ethiopia would further indicate the anti-Ethiopian nature of the exercises by putting Egyptian forces within range of Ethiopian soldiers and outside of their reported AU peacekeeping area of responsibility around Mogadishu.[102]

Ethiopia has strongly warned that the growing Egyptian military presence on its border poses a national security threat. The Ethiopian foreign affairs ministry released a statement on August 28 implicitly warning Egypt and the international community against Egyptian military involvement in the new AU mission and Somalia more broadly.[103] The statement repeatedly accused external actors—presumably Egypt—of destabilizing the region and said that it “must shoulder the grave ramifications” of doing so. Ethiopia framed these concerns as potential threats to its national security and actions that it “cannot tolerate.” Multiple local reporters have reported that Ethiopia began building up its military forces in the Ogaden region, which borders Somalia, in August.[104] Ethiopia also captured several airports in Somalia’s Gedo region, presumably to deny Egyptian and SFG access to the areas.[105]

The AU peacekeeping transition at the end of 2024 could trigger growing tensions into a regional conflict. Ethiopian officials have implied that Ethiopian troops will stay in Somalia past 2024 if Ethiopia has international and local support regardless of the SFG’s actions.[106] Local leaders and politicians in parts of southwestern Somalia have spoken out against the SFG’s plans to expel Ethiopian soldiers.[107] Ethiopia’s position is consistent with CTP’s previous assessment that Ethiopian forces will almost certainly try to remain in Somalia to maintain a buffer zone against al Shabaab and prevent an al Shabaab offensive into Ethiopia, as the group launched in 2022.[108] Ethiopia’s stated national security concerns about the Egyptian military buildup in Somalia further incentivize it to maintain this buffer zone.

Ethiopian forces remaining in Somalia past 2024 would provide a clear pretext for the SFG, with Egyptian support, to attack Ethiopian soldiers on Somali soil or along the border. The SFG has repeatedly condemned Ethiopia for violating its sovereignty throughout 2024 and threatened to retaliate.[109] Sisi has warned that Egypt would protect Somalia from any threats to its sovereignty on multiple occasions and explicitly threatened Ethiopia to “not try Egypt, or try to threaten its brothers especially if they ask it to intervene” after meeting with the Somali president in January.[110] Egypt’s GERD concerns also give it internal reasons to support military intervention against Ethiopia. Egypt wrote to the UN Security Council on September 1 that Ethiopia’s unilateral policy on the GERD “threatens the stability of the region” and that Egypt is “prepared to take all measures and steps guaranteed under the UN Charter” to defend itself after Ethiopia began the fifth stage of filling the GERD.[111]

The dispute may also lead to proxy conflicts in both countries between local actors and the federal governments. Ethiopia’s strong ties to various local actors in Somalia also increase the risk of an armed proxy conflict in Somalia between the SFG and pro-Ethiopian regional Somali administrations, even if Ethiopian forces withdraw. Multiple leaders and politicians in Somalia’s Jubbaland and South West states have spoken out against the SFG’s plans to expel Ethiopian troops.[112] Many of the Somali forces that operate in these states alongside Ethiopian soldiers respond to their clan and regional leaders, not federal entities, such as the Somali National Army or the SFG.[113] Disagreements between the federal government and these local factions have historically led to clashes between local and national forces, often the local factions receiving external backing from Ethiopia or Kenya.[114]

Tensions over the dispute have grown between the SFG and the South West State (SWS) government in September, which may lead to a military clash. The SFG has already begun retaliating against local politicians speaking out in favor of Ethiopia, marginalizing these communities and increasing the risk of an internal conflict.[115] Somali officials including the prime minister and president have also increased outreach to local leaders to try to find a peaceful solution.[116] A senior regional official and local journalist denied Somali media reports that the SFG deployed Turkish-trained special Haramcad special police and Gorgor commandos to the de jure SWS capital, Barawe, on September 16.[117] Such a deployment would be a clear precursor to infighting given that the SFG typically deploys special forces during conflicts with regional governments due to the command and control issues the SFG has with local forces and their allegiance to shared clan ties.[118]

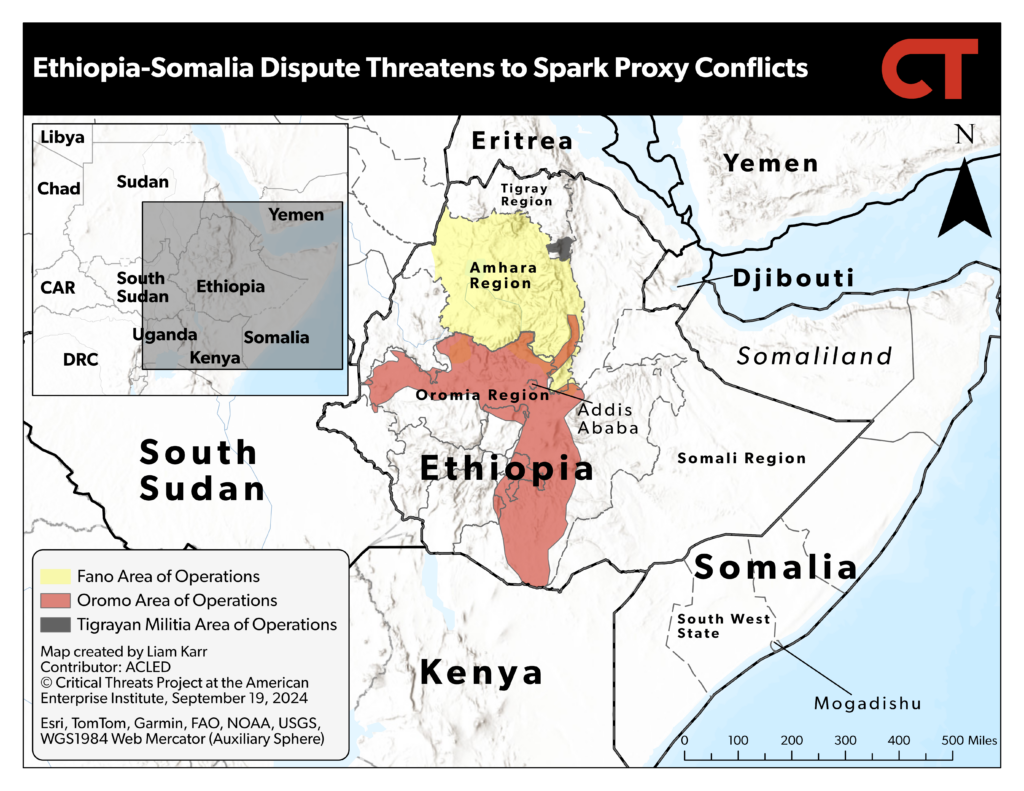

Figure 5. Ethiopia-Somalia Dispute Threatens to Spark Proxy Conflicts

Note: “DRC” stands for Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The SFG has also threatened to support ethno-nationalist insurgents in Ethiopia. Somali Foreign Minister Ahmed Moalim Fiqi said in mid-September that the SFG would consider establishing contact with rebels if Ethiopia followed through on its agreement with Somaliland but that the crisis had not yet “reached that stage.”[119] Ethiopia is facing several ethno-nationalist insurgencies across the country. A loose collection of decentralized Amhara militias known as Fano have been waging an insurgency against the federal government in northern Ethiopia since August 2023 and captured several key points along the Sudanese border and near Ethiopia’s second-largest city in September 2024.[120] The Fano insurgency overlaps with a conflict between federal forces, and Oromo insurgents that also sometimes fight Fano in central Ethiopia.[121] The federal and regional governments in Tigray are also still working to implement the 2022 peace agreement that ended the Tigray war, which has caused clashes and threats of violence over disputed areas between Amhara and Tigrayan militias.[122] Former insurgents in the majority ethnically Somali region in eastern Ethiopia have also claimed that the Ethiopian government’s retaliatory actions against Somali citizens are threatening a 2018 peace deal that ended their over 30-year insurgency.[123]

The Ethiopia-Somalia dispute has weakened the SFG’s counterterrorism efforts, undermining US counterterrorism goals to weaken al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab. The SFG has given priority to these issues over its counterinsurgency campaign against al Qaeda affiliate al Shabaab, undermining the fight against the group and contributing to its retaking territory in central Somalia that the SFG had captured in 2022 in a US-backed counterterrorism offensive that top US officials called “historic” and “impressive.”[124]

The fallout surrounding the port deal has weakened counterterrorism cooperation with critical counterterrorism partners such as Ethiopia and the UAE. CTP assessed that Somalia’s agreement with Turkey alienated the UAE, contributing to the UAE decreasing its financial and training support for Somali forces.[125] The SFG’s threat to expel Ethiopian troops could lead to opportunities for al Shabaab by either creating a force gap if Ethiopian forces leave or decreasing the SFG’s legitimacy and increasing popular anti-Ethiopian sentiment if they stay, which would boost al Shabaab recruitment.[126]

Figure 6. Al Shabaab Area of Operations: As of April 3, 2024

Note: “S. Sudan” stands for South Sudan.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database Project.

The growing tensions surrounding the Egyptian military buildup have also jeopardized Turkish-led peace talks between Ethiopia and Somalia. Turkey is the second-largest foreign investor in Ethiopia, with an estimated $2.5 billion in projects in the country at the end of 2021, and also provided TB2 Bayraktar drones to the Ethiopian government during the Tigray civil war.[127] Turkey has used its leverage with Ethiopia and Somalia to mediate talks between the two sides in July and August.[128] The effort has failed to yield a breakthrough, both sides have accused each other of wanting to destabilize the other, and a third round of talks scheduled for September 17 was postponed days prior.[129] The Somali minister of foreign affairs left the August meeting blaming Ethiopia for the talks’ collapsing.[130] Ethiopia also blamed Somalia for “colluding with external actors aiming to destabilize the region” instead of pursuing the peace talks.[131]

Turkey also risks alienating Ethiopia and diminishing its status as a negotiator due to its growing ties with Egypt and Somalia. Sisi met with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan on September 5 for the first time since Sisi took power in 2013, which led Turkey to cut ties with Egypt and shelter the Muslim Brotherhood leaders that Sisi overthrew.[132] Turkey has also been a steadfast supporter of Ethiopia on the GERD issue in recent years.[133] Egypt and Turkey signed 17 bilateral agreements during Sisi’s visit and discussed the need to “preserve the unity and territorial integrity” of Somalia among other issues.[134]