For decades, the United Nations was the primary institution overseeing peacekeeping missions in Africa. But the U.N. hasn’t launched a new mission since 2014, and its missions in Mali and the Democratic Republic of the Congo were forced to shut down amid rising insecurity and host-country resistance.

As the U.N. pulls back, African institutions are stepping up. The African Union and regional organizations oversee 10 peace operations with more than 70,000 men and women serving in 17 countries. In 2022, the AU matched its highest total of new missions by launching four peace operations.

Many observers now argue that the future of interventions on the continent will be African led. These missions, under the umbrella of African institutions and primarily staffed by African Soldiers, are, at their best, nimble, quick to respond and willing to aggressively engage enemies in ways U.N. missions are not.

“African-led PSOs [peace support operations] have demonstrated a wealth of experience, skills, capacity and knowledge despite the limited resources and funding,” wrote Dr. Andrew Yaw Tchie of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs in an article for the journal Global Governance. “African-led PSOs are at a unique point to not only adjust and adapt, but also become a key asset in dealing with future instability and continue to plug in a gap which the UN PKOs have not been fully successful in doing.”

African peacekeepers already are among the most experienced and battle-tested in the world. In 2000, African peacekeepers made up about 20% of all forces in U.N. missions. By 2020 that figure had grown to more than 50%.

But questions remain as to how the next generation of missions will be constructed and mandated. What types of crises will they seek to address? Who will fund them? Can they work to resolve conflicts through dialogue? As leaders chart the path forward, a unique African model of how, when and where to intervene is developing.

Different Shapes for Different Problems

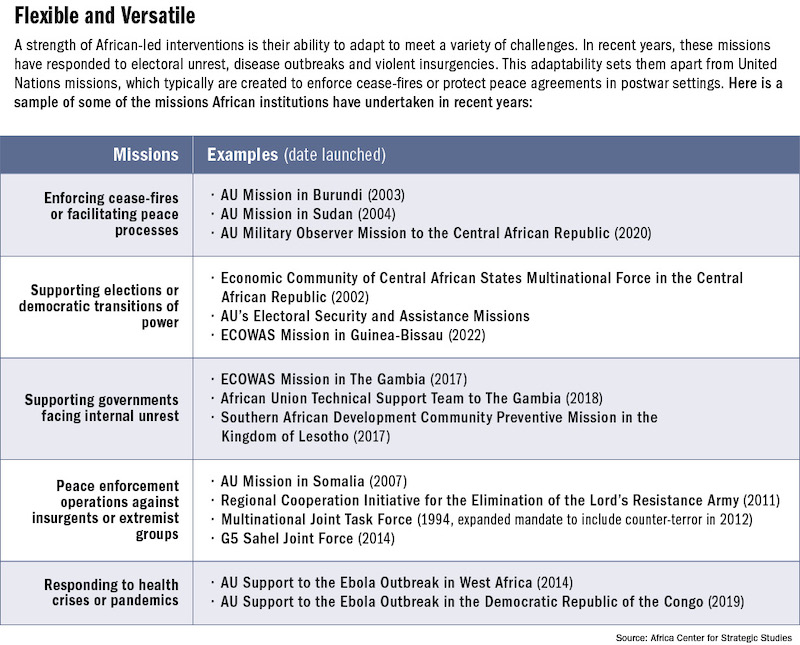

One advantage of the African-led missions is their versatility. There are large-scale missions mandated by the AU, like the mission in Somalia, which began in 2007 and included up to 20,000 troops. There also are smaller missions authorized by the regional economic communities (REC) like the 630-person Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) intervention in Guinea-Bissau formed to help stabilize the country after a coup attempt. Finally, there are ad hoc missions built out of a coalition of countries to address a shared threat such as terrorism or banditry. An example of this is the 10,000-person Multinational Joint Task Force composed of Lake Chad Basin countries in response to terrorism and crime.

The AU’s African Peace and Security Architecture guides these missions, but many are now fairly independent of the AU. As of 2023, only three of the 10 African-led peace operations were AU-mandated and supported financially and logistically by the AU. Others, like the South African Development Community Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM), are organized by a REC while operating under the framework of the AU’s African Standby Force (ASF).

Observers say a move toward more local control of missions is a good thing. They say that regional bodies and neighboring countries have a greater stake in the outcomes than do peacekeepers from far away.

“When it comes to peace enforcement, the motivation of troop-contributing countries is key,” Maj. Gen. Richard Addo Gyane, commandant of the Kofi Annan Peacekeeping Training Centre, told ADF. “If something happens in Nigeria, I would rather go and fight because I know it could affect Ghana easily. There is something for me to fight for.”

Similarly, these regional coalitions can be formed and deployed faster than those developed through a slow-moving bureaucratic process. The 2002 protocol establishing the ASF called for each region of the continent to be able to deploy an intervention battalion in 14 days. This urgency was necessitated by past acts of mass violence in which international intervention came too late to save lives.

Although the ASF structure is in varying levels of readiness, Dr. Cedric de Coning, a senior advisor to the African Centre for the Constructive Resolution of Disputes and an expert on peacekeeping, said that speed should be one of the greatest assets of African-led peace operations. He said interventions have been most effective using a “just-in-time” model in which coalitions of countries are built to quickly intervene when a crisis breaks out.

“The comparative advantage of the AU and all the African countries is that they can deploy fast, and they’re willing to be more robust,” de Coning said.

Tchie said this speed and self-sufficiency is a sea change from previous missions where countries had to wait for approval from an international body or a Western backer. “They’re doing most of the logistics and they’re using most of their own equipment,” Tchie told ADF. “These are frontline states putting their assets forward to be able to deliver on these operations. That is very different from the traditional U.N. model where you’re waiting for everyone to commit.”

A Philosophy of ‘Non-Indifference’

In 2019, the AU adopted a Peace Support Operations doctrine that made it clear it was willing to intervene in scenarios the U.N. traditionally avoids. The document highlights that the continental body has shifted from a philosophy of nonintervention in the affairs of member states to one of “non-indifference.”

“Non-indifference means that the AU and its Member States shall not stand by and not take action and may deploy even where there is no peace to keep, to prevent and/or respond to grave circumstances namely: war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide,” the doctrine states. “This is an obligation of AU Member States.”

The doctrine also allows for interventions without the consent of the member state to stop mass atrocities. But in practice, the AU has not always intervened when a member country is in turmoil. Civil wars in Ethiopia and Sudan did not elicit an AU mission. Militaries have led coups across the continent largely without AU or REC intervention.

“The African-led peace operations often fail to uphold the AU founding principle of non-indifference to leaders who, through war crimes, genocides, or unconstitutional seizures of power, abuse their citizens,” wrote Dr. Nathaniel Allen in the Africa Center for Strategic Studies paper, “African-Led Peace Operations: A Crucial Tool for Peace and Security.”

African-led missions have done better in the fight against violent extremist groups. Six of 17 African-led missions over the past 10 years were in response to radical Islamic extremism. These missions in places such as Mozambique, Somalia and the Lake Chad Basin take a high-tempo, muscular approach to peace support operations. This differs from the U.N., which typically is willing to intervene only to enforce a cease-fire or signed peace agreement.

African institutions also have shown a willingness to launch operations to restore constitutional order such as the 2017 ECOWAS mission to The Gambia. Missions also have been launched to ensure free and fair elections, in response to natural disasters or health crises like the West African Ebola outbreak, and to take on violent extremist groups like the Lord’s Resistance Army.

“There is no such thing as a cookie-cutter African-led peace operation,” Allen wrote.

The Challenge of Funding

Even when the will to intervene is there, funding is a challenge. Many African-led missions rely heavily on donor support.

The only recent mission to be financially self-sustaining has been SAMIM, Tchie found in his research. Other missions have needed support to last beyond 30 days. This is not surprising since the AU itself relies on donor support for about 70% of its budget and has stated that more than 40% of member states do not pay their yearly dues. An AU Peace Fund created in 2002 to support operations has been underfunded. Even the Peace Fund’s goal of $400 million is not enough to sustain long-term missions, experts say.

There is some cause for optimism. In December 2023, the U.N. Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution that will let it consider supporting the budget of AU-led peacekeeping missions on a case-by-case basis.

But, observers believe, in the future, these missions must be self-sustaining.

“By avoiding dependency on partners, African-led PSOs can reduce their transaction costs, avoid loss of agency and design missions according to the financial means of the bodies and member states that deploy these operations,” Tchie and de Coning wrote in an article for the Journal of International Peacekeeping.

Prioritizing Conflict Resolution

Although African-led missions have shown an ability to counter insurgencies and protect civilians, the process of building a lasting peace often is elusive. African-led missions are primarily military missions with military objectives.

Although most AU missions are led by a civilian representative of the AU chairperson, their personnel are nearly entirely military. The missions have a small civilian staff to deal with complex issues that drive conflicts such as political affairs; legal issues; humanitarian needs; disarmament, demobilization and reintegration; and other matters.

Tchie and de Coning believe these future missions will need to prioritize a political resolution to conflicts and address underlying drivers of instability. This will require a greater investment in the civilian component of a peace operation. They believe military efforts should be made to allow space for negotiation. That way a durable, political agreement can emerge.

“If the underlying drivers are not addressed, the conflict will not be resolved, and violence will return,” Tchie and de Coning wrote.

In too many countries, missions have been able to silence the guns, only to see a quick return to violence because the warring parties did not participate in a peace process and the underlying drivers of violence were not addressed. The AU has mechanisms for conflict early warning and mediation to resolve disputes, but experts say these are underdeveloped.

“Serving a political project or peace process is critical to the credibility and legitimacy of any African-led PSO,” Tchie and de Coning wrote. “Without a political project, there is no sustainable end-state or exit strategy.”

As African-led missions evolve, their ability to respond to complex threats will have major implications for the continent’s prosperity and stability.

“It is no stretch to argue that future peace and security on the continent depends upon the continued growth and evolution of African-owned modalities of conflict prevention and resolution,” Allen wrote. “To achieve their full potential, the AU, RECs, and member states must reinforce the successes and address the shortcomings of African-led peace operations.”