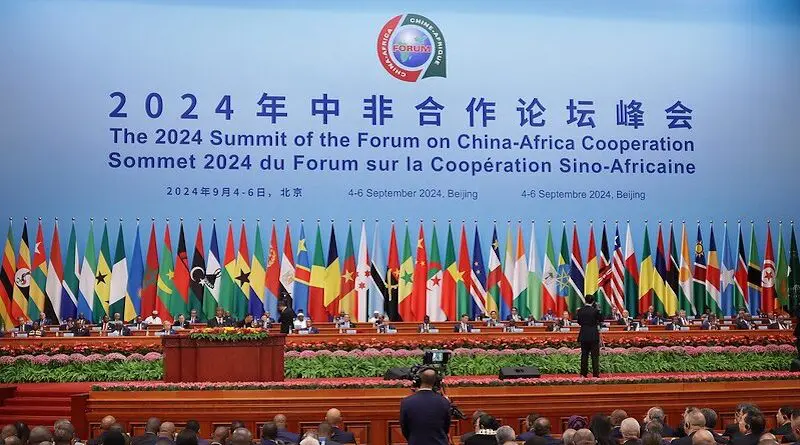

It was disappointing to see so little in-depth discussion among the US national security community at the recent 2024 Forum On China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) outside of the usual circles of Africanists and China specialists. The summit meeting provides a crucial roadmap as to how relationships with the states of the African continent—and within the Global South more broadly—need to be conducted.

For the rising and developing states of the Global South, the democracy-authoritarian axis is less critical than what might be termed the “prosperity-legitimacy equation”: that governments will be assessed positively or negatively to the extent that they are able to take steps to provide a more stable, middle-class lifestyle and at minimum guarantee a basic level of access to staples, consumer goods, and welfare services. China, of course, offers its system of party management of state and society to argue that a vanguard elite is best positioned to deliver positive outcomes—as Chinese President Xi Jinping laid out in his August 2021 address on “Boosting Common Prosperity” to the meeting of the Central Committee on Financial and Economic Affairs. This is why Nils Schmid, the foreign affairs spokesman for the Social Democrats in the Bundestag, stressed in his comments in the Winter 2022 issue of Orbis that “democracies and socially oriented market economies” had to demonstrate their capacity “to generate growth and equality, equal opportunities, and social cohesion.”

The prosperity-legitimacy equation requires solving the “energy-food-water” trilemma. Sustaining basic standards of living and creating conditions for growth and development—while also avoiding further climate and environmental shocks—requires finding ways to guarantee access to clean water (for drinking, agriculture, and industry), sufficient food supplies (especially protein), and energy (to power all aspects of life). If the trilemma is not addressed, then the health, economic, and energy security of a country is imperiled. On the last point, many of the emerging technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as well as proposed “green” solutions to the water and food crises, will require large amounts of energy which will need to be sustainable, reasonably inexpensive, and also not contribute to carbon emissions.

Increasingly, most countries in the world will face tremendous, if not existential, challenges from “climate change, technology, disease, and financial crises” as a 2021 Global Trends assessment concluded. Traditional security concerns—including invasion, as Ukraine’s ongoing struggle demonstrates—have not disappeared, but for most countries, having military security guarantees will not generate energy nor guarantee food supplies.

Not surprisingly, a major theme of this year’s China-Africa summit was green energy. In the communique from the gathering, participants stressed that “energy is central to the continent’s economic and social development.” Chinese interest in this is not rooted in abstract altruism: The continent contains much of the raw material Beijing needs for new technologies, which makes it integral to China’s own security and prosperity. Items offered by Beijing at the summit—transferring capabilities that will enable African governments to adapt to climate and industrial disruptions, enhancing power capacity from “clean” sources, and promoting so-called “green industrial developments”—are designed to secure the extraction and processing supply chains for the commodities and components needed for Fourth Industrial Revolution goods and services.

African governments are eager to accept any sources of finance and technology that will enable them to navigate the trilemma. But in the aftermath of the FOCAC summit, African leaders were also signaling that, despite their warm relationships with Beijing, they are interested in diversifying their portfolios and looking for Western “private-sector engagement and … public-private partnerships” with Western governments and companies.

Yet the countries of the continent—and within the Global South more broadly—will not wait indefinitely. Even when China’s efforts to claim leadership to rival the United States is not endorsed, Beijing’s “message of rewriting the international order resonates with African nations that feel frustrated and abandoned by their traditional Western partners.” At the summit, a Chinese version of wandel durch handel (change through trade) is well underway: Beijing hopes that its economic leverage and its efforts to rewire the global trading system will induce political change that will redound to its benefit.