Key Takeaways:

- North Africa–Sahel. Algeria and Morocco are vying for economic and political influence in the Sahel to assert themselves as regional leaders and legitimize their positions on the Western Sahara, a disputed territory on the coast of northwest Africa. Morocco is spearheading its engagement with the Sahel through an initiative to connect the landlocked central Sahel states to the Atlantic Ocean via a Moroccan port in Western Sahara. Algeria has tried to counter Morocco’s Atlantic initiative through a combination of carrots and sticks. However, its strained bilateral relations with its Sahelian neighbors—especially Mali—undermine its position. Algeria has turned to its longtime Russian partners for assistance, but Russia’s destabilizing activity in the Sahel may be driving a wedge between the two partners.

- Libya. Recent political disputes and troop mobilizations are destabilizing the fragile political ecosystem that has been in place since a UN-brokered ceasefire in 2020. The UN-backed Western-based government is attempting to replace the Eastern-backed Central Bank of Libya (CBL). The crisis may also cause an economic fallout due to retaliatory cuts to oil production and the CBL’s inability to pay government salaries. The CBL issue may exacerbate a dispute over control of another Tripoli-based body that has a say in all major constitutional changes and appointments, including positions like the CBL board of directors. The crises could end violently due to the widespread lack of institutional legitimacy. The Eastern-based Libyan National Army (LNA) separately deployed forces to southwestern Libya in early August in an unsuccessful bid to bloodlessly capture key infrastructure points. The LNA deployments may alternatively be related to a quid pro quo that has resulted from growing engagement between Libyan warlord and LNA head Khalifa Haftar and the central Sahelian countries.

- Burkina Faso. JNIM carried out another mass-casualty attack. The latest attack increases pressure on the strategic central-north capital of Kaya and further threatens support for the embattled Burkinabe junta. CTP has previously assessed that Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) likely aims to establish uncontested support around Kaya by quashing armed civilian resistance and degrading security forces’ capability and will to conduct patrols and operations outside their bases. The attack adds to growing internal pressure to overthrow the Burkinabe junta.

Assessments:

North Africa–Sahel

Algeria and Morocco are vying for economic and political influence in the Sahel to assert themselves as regional leaders and legitimize their positions on the Western Sahara, a disputed territory on the coast of northwest Africa. Morocco is spearheading its engagement with the Sahel through an initiative to connect the landlocked central Sahel states to the Atlantic Ocean. Morocco initially said that it was ready to make “its road, port, and rail infrastructure” available to Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger in September 2023 and announced a more comprehensive plan in November 2023.[1] The initiative involves linking Morocco’s transportation and shipping infrastructure to the Sahelian countries and implementing other large-scale development projects to introduce advanced agriculture and solar energy, improve education, give vocational training, and improve health care services.[2] The foreign ministers from Burkinabe, Malian, and Nigerien juntas—which compose the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), a regional confederation—met their Moroccan counterpart in Marrakech in December to continue planning the “Morocco initiative” and create a task force to work toward implementing aspects of the project.[3]

Morocco has leveraged its growing relationship with the Sahelian states to increase bilateral cooperation. Burkina Faso had already signed several agreements customs and development agreements with Morocco in June 2023.[4] The two countries signed a military agreement in June 2024 that includes training, joint exercises, knowledge exchange, and military-health cooperation.[5] Niger sent a high-ranking ministerial delegation that included the prime minister and the economic, foreign affairs, and state ministers in February 2024.[6] The Chadian and Moroccan foreign ministers discussed resuming the Chad-Morocco cooperation commission in 2025 and signed five agreements covering customs, forest management, and education and research when meeting in August 2024.[7]

Figure 1. Moroccan Outreach to the Central Sahel

Source: Liam Karr and Avery Borens.

The initiative is also part of Morocco’s plans to support its claim to Western Sahara. Spain left Western Sahara in 1975, leaving Morocco, Mauritania, and the Algeria-backed, Sahrawi Arab–affiliated Polisario Front battling for control of the region. Morocco consolidated control over 80 percent of the region, while the Polisario militants retained 20 percent after several victories that forced Mauritania to withdraw before the ensuring military stalemate led to a UN-mediated ceasefire in 1991.[8]

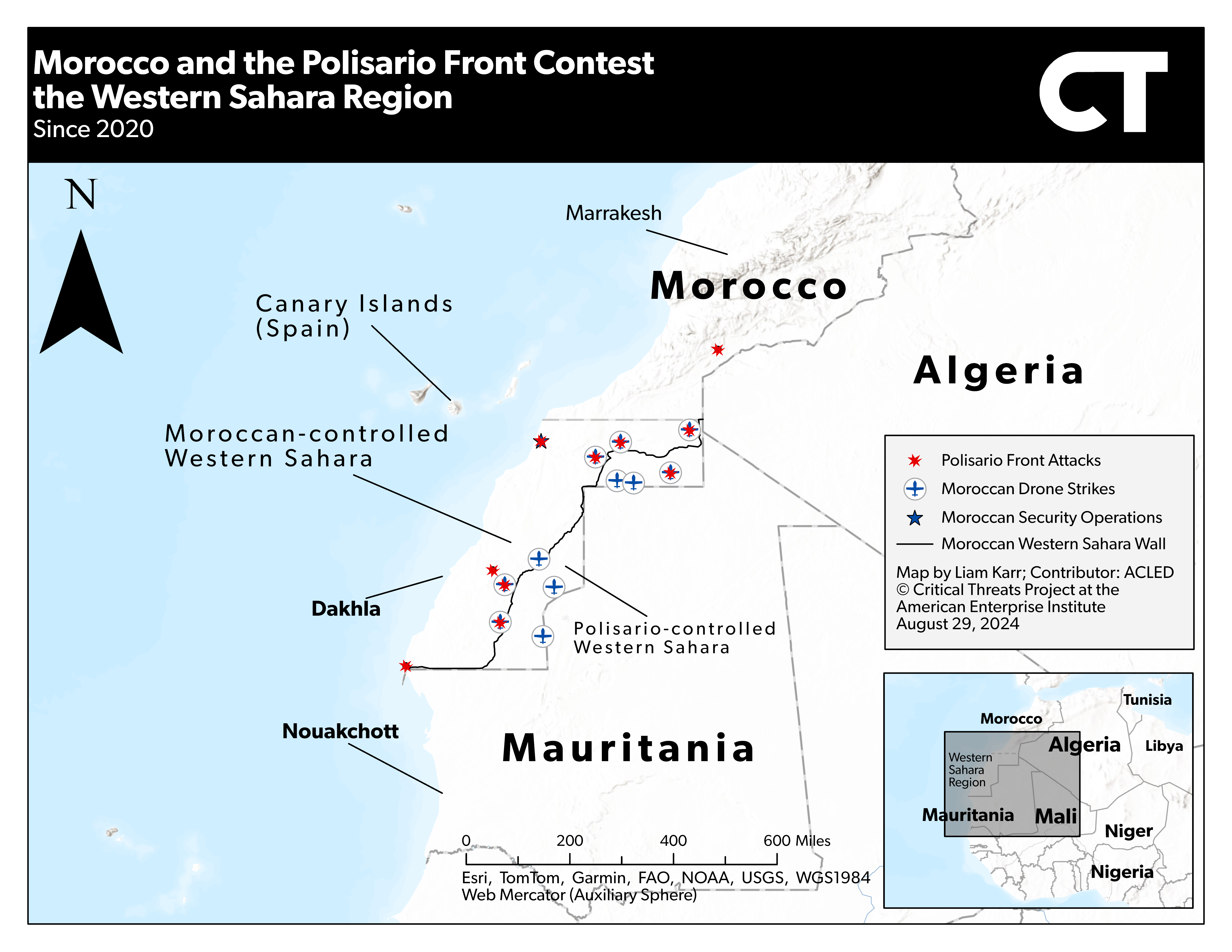

Figure 2. Morocco and the Polisario Front Contest the Western Sahara Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The ceasefire held until 2020. Morocco began consolidating international support for its control over the region—including US recognition of Moroccan sovereignty—in 2019 and violated the UN buffer zone to clear a Polisario blockade in November 2020.[9] These moves led the Polisario Front to resume low-intensity attacks against Morocco.[10] Algeria cut diplomatic ties with Morocco in August 2021 in retaliation for Morocco’s moves and has since cooperated with Iran to support Polisario militants.[11] US officials have maintained contact with all stakeholders and have worked with the UN to push mediation efforts.[12]

Morocco has linked the initiative with its $1.2 billion port project in the Western Saharan port city of Dakhla. Morocco plans to use the Dakhla port as the nexus for the landlocked Sahelian countries.[13] Morocco expects to finish constructing the port in 2028, which will handle 35 million tons of goods annually that will connect to North and West Africa through the coastal highway.[14] Greater international engagement in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara would help legitimize Moroccan control over Western Sahara. The initiative has already rallied preexisting political support among the Sahelian countries to recognize Morocco’s claim to the disputed territory.[15] Chad also became the second of the central Sahelian countries to open a consulate in Dakhla in August 2024, joining Burkina Faso.[16]

Algeria has tried to counter Morocco’s Atlantic initiative through a combination of carrots and sticks, but its strained bilateral relations with its Sahelian neighbors undermine its position. Algiers initially suspended loan payments to all countries involved in the initiative in January 2024.[17] It soon unveiled plans in February 2024 to develop “free trade zones” with Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Tunisia to enhance infrastructure and bolster economic relations.[18] However, Algeria and the Sahelian states have not agreed to move forward with these plans. Algeria has also tried to counter Morocco’s advances in the Sahel through greater outreach to its North African neighbors in Libya and Tunisia.[19]

Figure 3. Algerian Outreach to the Central Sahel

Source: Liam Karr and Avery Borens.

Algeria has struggled to maintain ties with Mali during the past year. Mali has escalated military activity against separatist Tuareg rebels in northern Mali near the border with Algeria, which broke a 2015 Algerian-brokered peace deal.[20] Algeria strongly supported the 2015 peace agreement and met with rebel leaders and prominent clerics to salvage the deal in December 2023 due to fears that renewed hostilities in Mali would mobilize the Tuareg population in Algeria and cause refugees to flee into Algeria.[21] Mali withdrew its ambassador from Algeria in retaliation for those efforts.[22] Mali then accused Algeria of undermining its sovereignty as it formally withdrew from the peace agreement in January 2024.[23] Algeria conducted live ammunition military drills on its border with Mali in February 2024 to deter Malian overreach.[24]

Malian and Russian forces launched an offensive to clear longtime rebel sanctuaries along the border in July 2024. The offensive resulted in a rebel- and al Qaeda–linked ambush that killed over 100 Malian and Russian soldiers.[25] Mali has since increased drone strikes in this area, killing dozens of civilians from Mali and surrounding countries that participate in the local mining economy and forcing wounded and refugees to flee into Algeria.[26] Algeria’s representative to the UN called for accountability for human rights abuses in a statement on the strikes on August 27.[27]

Figure 4. Malian and Russian Forces Battle Tuareg Insurgents in Northern Mali

Note: “B. Faso” is Burkina Faso.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Algeria has worked on improving its complicated relationship with Niger to maintain some ties with the AES and address trans-Saharan migration concerns. Algeria initially pushed against a proposed regional intervention to overthrow the Nigerien junta after it took power in July 2023 and positioned itself as a mediator to the regional crisis.[28] However, the junta rejected the proposed six-month transition plan and accused Algeria of “manipulation.”[29] Algeria subsequently suspended its initiative due to “inconclusive” discussions and “legitimate questions” about Niger’s willingness to accept Algerian mediation.[30]

Algeria’s anti-immigrant policies have also caused tensions with Niger. Major trans-Saharan migration routes from Mali and Niger run through Algeria.[31] Algeria maintains a forceful anti-immigrant policy that involves mass arrests and expulsions of tens of thousands of migrants.[32] Migrant trafficking is an illicit local economy that benefits the army and state in Niger, unlike in Mali where organized crime actors including al Qaeda–affiliated militants control most major smuggling routes.[33] The Nigerien junta lifted an EU-backed migration law in November 2023 that criminalized the transport of migrants from northern Niger to Algeria and Libya to better reap the financial and patronage benefits of the migrant trafficking.[34] Algeria and Niger summoned each other’s ambassadors in April 2024 over a dispute related to Algeria forcibly expelling tens of thousands of migrants to Niger.[35]

Algeria has sought to maintain its ties with Niger despite these disagreements. Algerian President Abdelmadjid Tebboune and Nigerien Prime Minister Ali Lamine Zeine led high-ranking delegations that met in Algiers in August.[36] The Algerian army chief of staff, Algerian foreign affairs minister, and Nigerien defense minister participated in the discussions.[37] The parties discussed ways to strengthen bilateral cooperation, such as military and security coordination and infrastructure projects, including the African gas pipeline that aims to link Nigeria and Europe via Algeria and Niger.[38]

Algeria has turned to its longtime Russian partners for assistance, but Russia’s destabilizing activity in the Sahel may be driving a wedge between the two partners. Algeria has maintained a strong relationship with Russia dating back to the Soviet Union, which cultivated strong defense ties and cooperation in international institutions that persist despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[39] Russia is also a key military and political partner for the Malian and Nigerien juntas, and CTP previously noted that Russian forces have been essential to Mali’s offensives on rebel-controlled areas in northern Mali since 2023.[40] French media reported in March 2024 that Russia was acting as an intermediary between Algeria and Mali to resolve their dispute.[41] Pro-Moroccan media claimed that Algeria asked for Russian mediation to repair its relationship with Mali and Niger in April 2024.[42]

Algeria has made increasingly frequent and hostile statements about the activity of Russian soldiers in the Sahel. Algeria has always been skeptical of Russia’s military meddling in Africa. Algeria has loosely supported the UN-recognized Government of National Accord that is fighting Russian-backed Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar and condemned the presence of all foreign forces in Libya.[43] President Tebboune also said in 2022 that Mali would be better off spending the money that it costs to hire the Kremlin-funded Wagner Group on development projects.[44] Algeria directly relayed its fears of the Wagner Group’s destabilizing impact in Mali to Moscow in May 2024.[45] Algeria’s representative to the UN called for an “immediate end” to mercenary activities and related human rights abuses in Mali on August 27, presumably referring to Russian forces in Mali.[46]

Libya

Recent political disputes and troop mobilizations could destabilize the fragile political arrangement in Libya that has been in place since a UN-brokered ceasefire in 2020. Libya is divided between the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) and allied militias that control western Libya and the Libyan warlord and Libyan National Army (LNA) head Khalifa Haftar, who controls the Libyan parliament—formally known as the House of Representatives—based in eastern Libya. Haftar’s LNA launched an unsuccessful offensive to seize Tripoli in 2019, ending in a UN-brokered ceasefire in 2020 that produced the GNA as an interim government until scheduled elections in 2021. However, Libya’s institutions have continued to decay as election and reunification deadlines have passed while corrupt elites on both sides remain in power.[47]

Political disputes over control of key Western-based institutions have increased tensions across Libya. The relationship between Central Bank of Libya (CBL) head Sadiq al Qabir and GNA Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeiba has deteriorated since mid-2023 due to fallout surrounding east-versus-west power struggles over control of Libya’s National Oil Corporation—which sells all Libyan oil and sends all revenue to the CBL—and subsequent corruption and patronage spending.[48] The CBL is in GNA-controlled Tripoli but controls all of Libya’s oil funds, which compose 90 percent of Libya’s fiscal revenues and 68 percent of its total GDP.[49] The CBL has worked with both governments to pay government salaries and support their individual patronage networks.[50] However, the recent tensions have led Qabir to grow his ties with Haftar’s regime in eastern Libya while withholding funds for Dbeiba’s allies.

Dbeiba and his allies are now attempting to replace Qabir to gain control of the CBL. Opposing militias surrounded the CBL headquarters on August 11, and unknown militants kidnapped the CBL’s IT director on August 17, leading the bank to shut down for one day.[51] The GNA Presidential Council used the move to justify dismissing Qabir.[52] Dbeiba voiced his support for these efforts and instructed Libyan embassies to inform foreign officials dealing with the bank that Qabir was no longer the bank head.[53] The GNA announced an agreement with armed groups to secure infrastructure including the CBL on August 24 and appointed a new interim governor that promised to return 90 percent of CBL employees to work by August 29.[54] Qabir has rejected the move, however, and said he is responsible to the Haftar-backed Libyan parliament, which has made multiple decrees in support of Qabir since 2023.[55]

The conflict could cause an economic crisis that would further destabilize the situation. The Haftar-controlled eastern government retaliated against the GNA on August 26 by closing oil production and exports until Qabir “resumes his functions.”[56] The move impacts 65 to 90 percent of Libya’s oil fields and terminals and has already halved Libya’s oil output.[57] Qabir has also said that the government may not be able to pay August salaries due to the conflict, while the GNA-appointed interim governor promised on August 28 to resume salary payments within two days but does not have the passwords to access the banking system.[58] Unilateral and forcible actions to replace the CBL head also risk Libya’s continued access to international financial institutions and markets.[59]

The CBL crisis may exacerbate another institutional dispute over control of the Tripoli-based Libyan High Council of State (HCS).[60] A UN-backed 2015 agreement created the HCS as a power-sharing body to the eastern-based Libyan parliament that must agree to all major constitutional changes and appointments, including positions like the CBL board of directors.[61] The HCS Presidency has been contested since the August 6 elections were decided by one vote between former head Khaled al Meshri and his successor Mohammed Takala, who had been in office for one year.[62] Meshri is more amenable to working with the Libyan parliament, which presumably led pro-Dbeiba forces to block the HCS from holding a Meshri-led special session on August 28 to agree on a new president.[63] Analysts have assessed that Dbeiba and the GNA presidential council may de jure dissolve the HCS and Libyan parliament in an attempted power grab, which would inflame the ongoing political dispute.[64]

Neither government has significant political legitimacy, increasing the risk that disputes are resolved by force. The GNA presidential council has largely been symbolic since forming in 2020, lacks the right to dismiss the CBL head, and has stayed in power past the December 2021 election deadline.[65] The Haftar-controlled Libyan parliament has not stood for election since 2014 or met quorum since 2020.[66] The GNA sent a delegation of officials and militia officers to the central bank on August 20 to force Qabir to step down.[67] Presumed GNA supporters also broke into the CBL on August 26.[68] Qabir said on August 27 that the CBL had been unable to operate due to militia threats and the kidnapping of four staff members.[69]

The LNA also deployed forces to southwestern Libya in early August in a potential attempt to take key infrastructure. The LNA claimed that the troops aim to secure the borders, combat trafficking, and stop terrorism.[70] However, analysts and media suspect that the operation originally sought to capture key areas controlled by the GNA, such as the Gahadames airport or Hamada oil and natural gas field.[71] Ghadames and Hamada both have economic value. Ghadames is along migrant smuggling routes and a key border crossing point near Algeria and Tunisia, whereas the Hamada oil field just finished its first phase of development and is projected to deliver at least 8,000 barrels of oil a day when it becomes operational in the coming month.[72] Tarek Megerisi, a senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, said that the LNA aimed to flip local militias to their side and capture the areas in a fait accompli. However, they peacefully abandoned the plan when they failed to gain enough local support and Tripoli put its forces on high alert.[73]

The LNA operation may also be related to a quid pro quo with Chad and Niger. A separate LNA brigade from the one operating near the Algerian border forces engaged unknown Chadian militants near the Chad-Libya border on August 19.[74] The Italy-based Agenzia Nova reported that the clash was part of the August “border operations” and a piece in a deal Haftar struck with Chad and Niger. The deal allegedly involves the LNA helping clear Chadian rebels and traffickers from the Libyan border to open agreed-upon free trade zones that would allow Haftar to ship oil to Niger and Chad to ship arms to Libya, circumventing the UN arms embargo.[75] The Haftar-backed government and Niger agreed to establish free trade zones along their border in August, supporting the existence of this broader deal. Chad has also historically cooperated with Haftar to pursue Chadian rebels that have rear bases in Haftar-controlled areas of Libya.[76] Chad and Niger did not make any statements on the LNA August mobilizations, indicating tacit consent, unlike Algeria, the UN, and Western countries, which urged restraint.[77]

The alleged deal reflects growing engagement between Haftar and the central Sahelian countries throughout 2024. European media reported that Haftar sent multiple delegations to Niger in early 2024 to discuss closer collaboration, including military cooperation.[78] Nigerien Interior Minister Mohamed Toumba also led two delegations to the Haftar-backed capital Tobruk in February and August.[79] Toumba discussed border-control cooperation in August and signed a memorandum of understanding to establish free trade zones along their shared border.[80] Haftar’s son, Saddam—who is also his special envoy and commander of LNA ground forces—also met with the Chadian President Mahamat Deby and Burkinabe junta head Ibrahim Traore in June and July, respectively.[81]

Burkina Faso

JNIM carried out a mass-casualty attack, increasing pressure on the strategic central-north capital of Kaya and Burkina Faso’s embattled junta. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) militants attacked Barsalogho village, nearly 25 miles from the Centre-Nord regional capital, Kaya, on August 24.[82] Western media sources claim the attack killed at least 100 villagers and soldiers.[83] Local media sources claimed the attack killed more than 208 people, most of whom were civilians that the army had reportedly enlisted to dig trenches around the town in preparation of an expected attack.[84] JNIM released a video showing dozens of bodies but has not released exact details about the attack’s total casualties or motive.[85] Burkinabe Security Minister Mahamoudou Sana acknowledged significant casualties and promised that security forces will “provide a firm response.”[86]

Figure 5. JNIM Intensifies Pressure Around Kaya

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

CTP has previously assessed that JNIM likely aims to establish uncontested support around Kaya by quashing Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland resistance and degrading the capability and will of security forces to conduct patrols and operations outside their bases. Kaya is a strategic point in north-central Burkina Faso that houses the main military base in the region between JNIM-contested territory and the capital, Ouagadougou.[87] JNIM had already increased the intensity of its attacks along the N3 road east of Kaya in May and June. The Kaya attack brought the number of people killed in JNIM attacks since May in the Namentenga and Sanmatenga provinces around Kaya to at least 420 people compared with just 199 in the first four months of 2024.[88] The increasingly severe activity around Kaya follows JNIM’s pattern of besieging towns—including provincial capitals—around Burkina Faso.[89] The group uses this strategy to consolidate control over rural areas, overwhelm weakened and isolated towns, and project shadow influence into besieged centers by controlling the economic activity in the surrounding areas.

The attack adds to growing internal pressure to overthrow the Burkinabe junta. High-casualty militant attacks preceded both successful Burkinabe coups in January and October 2022.[90] The junta survived a potential coup in early June after JNIM killed over 100 Burkinabe soldiers in what had been the deadliest attack on Burkinabe forces.[91] The junta has now suffered the deadliest attack against Burkinabe forces and potentially the overall deadliest attack in Burkina Faso in less than a month. JNIM militants ambushed a military convoy on August 9, killing more than 140 Burkinabe soldiers and nearly 50 civilians.[92]