Key Takeaways:

Ukraine. Mali and Niger cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine and other West African countries have criticized Ukraine after some Ukrainian officials claimed to support Tuareg separatist rebels in northern Mali. The moves from the pro-Russian Sahelian juntas are unsurprising, but countries not aligned with Russia have also criticized Ukraine. This criticism comes as Ukraine is trying to strengthen cooperation with West Africa to counter Russia’s growing influence in the region.

Turkey. Turkey’s parliament approved a motion to deploy its naval forces to Somalia as it seeks to implement deals signed in early 2024 that will make Turkey the main security force in Somali waters over the next two years as it builds the Somali Navy’s capacity. Somalia likely intends to use its partnership with Turkey to counter Ethiopia’s controversial port agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Turkey’s growing influence in Somalia is a major economic and geopolitical gain for Turkey that could jeopardize its ties with Ethiopia and shape the Turkish-Emirati rivalry in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa.

Somalia. Al Shabaab carried out its deadliest attack in Mogadishu since October 2022, which may be an effort to degrade government and popular morale after recent Somali Federal Government counterinsurgency operations.

Assessments:

Ukraine

Mali and Niger cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine and other West African countries have criticized Ukraine after some Ukrainian officials claimed to support Tuareg separatist rebels in northern Mali. Tuareg insurgents that CTP previously assessed had ties to both non-jihadist separatist rebels and al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate repelled a Malian-Russian offensive in northern Mali in late July, which resulted in the deaths of up to 84 Russian and 47 Malian soldiers.[1] The spokesperson of Ukraine’s military intelligence branch said on July 29 that “the [non-jihadist] rebels received the necessary information, and not just information” to enable the successful attack.[2] Multiple outlets also reported that the Ukrainian embassy in Senegal posted a video on Facebook that it has since removed that showed the Ukrainian ambassador alluding to supporting the rebels.[3] Mali cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine on August 4 following the claims of Ukrainian support. The Malian statement explicitly cited remarks from Ukrainian officials claiming to support the rebels and parroted Russian information narratives that brand Ukraine as “neo-Nazi . . . allies of international terrorism.”[4] The Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs formally responded to Mali’s criticism that it had failed to deny these allegations by retroactively denying any involvement in the attack on August 5 and branding Mali’s move as “short-sighted.”[5]

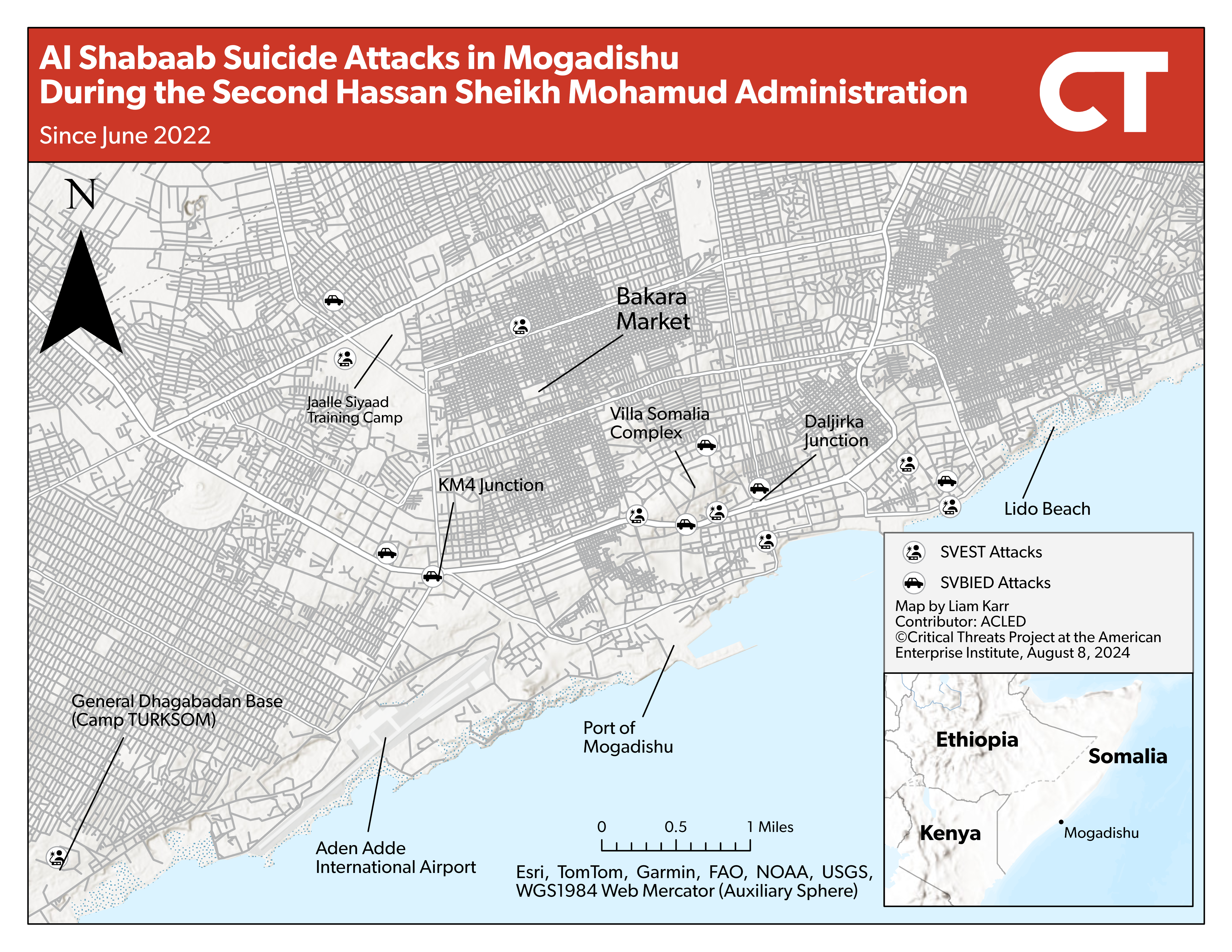

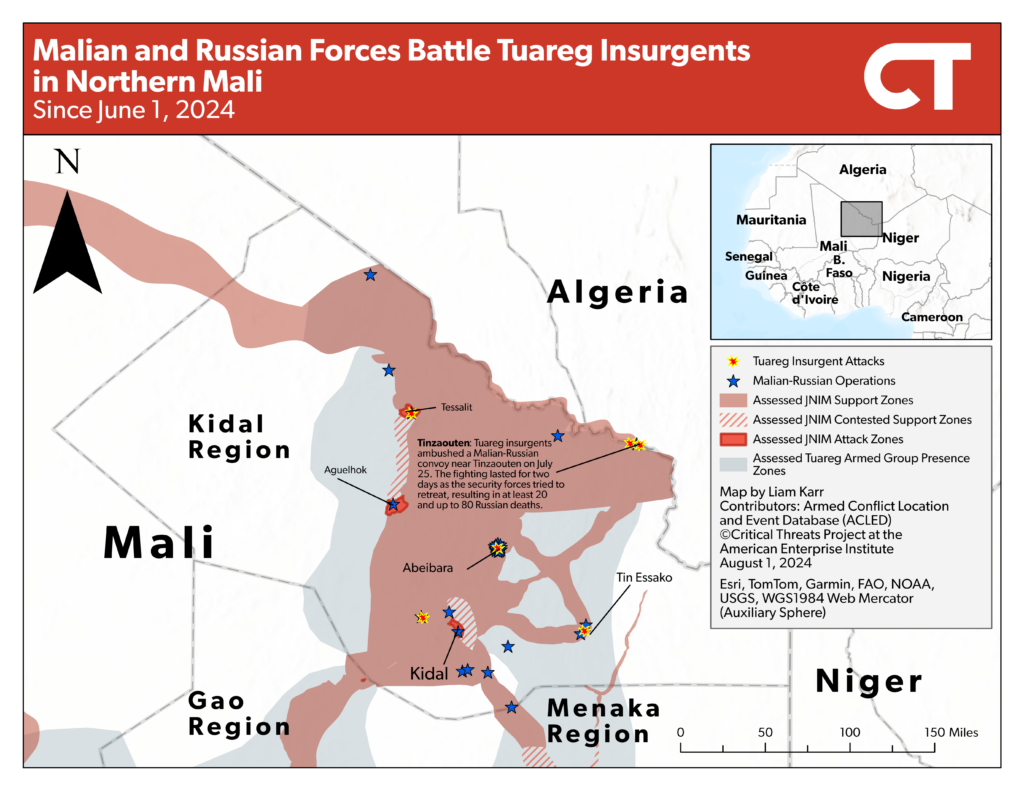

Figure 1. Malian and Russian Forces Battle Tuareg Insurgents in Northern Mali

Note: “B. Faso” is Burkina Faso.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location Event and Data Project.

Burkina Faso and Niger, Malian allies that also host Russian forces, have moved in solidarity with Mali. In response to the Facebook video, Burkina Faso called on the international community and African countries to denounce Ukraine’s actions and encouraged Ukraine to respect other nations’ sovereignty and not support “terrorist” groups.[6] Niger followed Mali’s lead and cut diplomatic ties with Ukraine on August 6.[7]

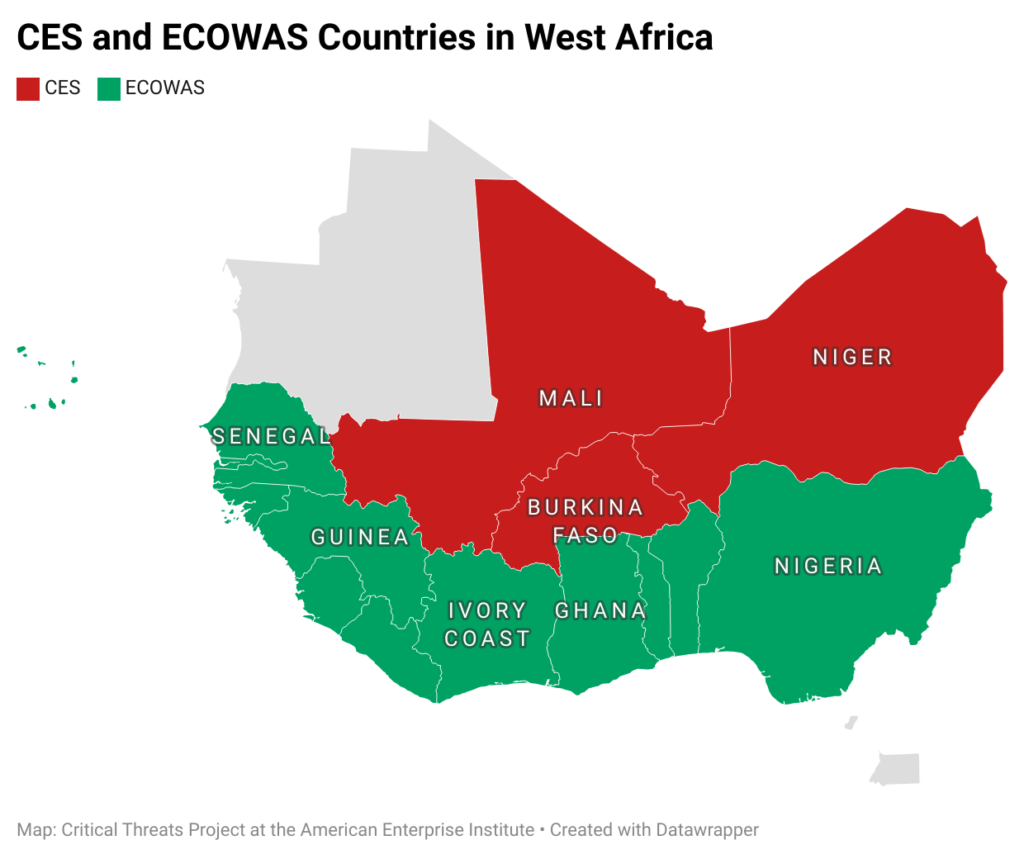

These moves are not surprising given the state of relations between the three Sahelian countries and Ukraine before the Tuareg insurgent attack. Mali and Ukraine have not had strong relations in recent years, amid the Malian junta’s growing ties with the Kremlin and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Mali was one of only seven countries that voted against a UN resolution calling for Russia to withdraw from Ukraine in February 2023, and it had abstained on two prior resolutions relating to the Russian invasion.[8] Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger all host Russian military personnel and have been working together as a pro-authoritarian and pro-Russian bloc called the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) since September 2023.[9] The three juntas announced their intentions to leave the relatively democratic and pro-Western Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in early 2024 and formed the Confederation of Sahel States (CES) in July 2024. The AES leaders have explicitly stated their desire to work with “sincere partners” like Russia and speak with “one voice” diplomatically, which is reflected in their shared rebuke of Ukraine in favor of continued cooperation with Russia.[10]

Figure 2. CES and ECOWAS Countries in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

West African countries not aligned with Russia and have tensions with the Russian-backed juntas have also criticized Ukraine. Senegal summoned and reprimanded the Ukrainian ambassador for the video, in line with its “neutrality” in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, rejection of any actions that “excuse terrorism,” and principles of “non-interference.”[11] ECOWAS also released a statement on August 5 extending its condolences to Mali and condemning “any foreign interference in the region that threatens peace and security.”[12] The timing of the ECOWAS statement indicates that the controversy surrounding Ukraine motivated ECOWAS given it occurred the same day as Mali’s and Burkina Faso’s actions against Ukraine and more than a week after the actual ambush. ECOWAS and its 11 unsuspended member countries have strong partnerships with the West and implemented sanctions on the AES juntas when they each took power by overthrowing democratically elected civilian governments.[13] Senegal is leading the ECOWAS effort to convince the AES countries to rejoin ECOWAS.[14]

ECOWAS’s and Senegal’s reprimands of Ukraine highlight their desire to avoid a proxy conflict in the region. African states don’t view themselves as players in the Russia-Ukraine war and have emphasized their neutrality and desire to continue developing their separate partnerships with Russia, Ukraine, and the rest of the West without foreign interference.[15] ECOWAS warned Russia against influencing the Niger crisis in the aftermath of the July 2023 Niger coup and condemned Russian-linked human rights abuses in Mali.[16] However, ECOWAS has clarified that regional countries are responsible for their bilateral agreements with Russia and that it holds those countries, not Russia, accountable for resulting actions.[17]

The diplomatic setback surrounding alleged support for the Tuareg rebels as Ukraine is trying to strengthen cooperation with West Africa to counter Russia’s growing influence in the region. The Ukrainian foreign minister toured Africa from August 4 to 8, visiting Malawi, Mauritius, and Zambia to strengthen ties and work towards African participation in “global efforts to restore a just peace for Ukraine and the world.”[18] The Ukrainian ambassador to Senegal also gave an interview to French media in late July discussing Ukraine’s ambitions to strengthen diplomatic, economic, and even military cooperation with West Africa to grow partnerships and counter Russian influence.[19] ECOWAS members like Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea-Bissau have emerged as economic and political partners for Ukraine despite both maintaining ties with Russia.[20] Ukraine has opened new embassies across Africa and seeks to return trade to prewar levels despite Russia’s military efforts to destroy Ukraine’s ability to ship exports through the Black Sea.[21]

Turkey

Turkey’s parliament approved a motion to deploy its naval forces to Somalia as it seeks to implement deals signed in early 2024 that will make Turkey the main security force in Somali waters over the next two years as it builds the Somali Navy’s capacity. Turkey will deploy an unspecified number of naval forces to Somalia to help the Somali Federal Government (SFG) protect its territorial waters and build the Somali forces’ capacity to counter terrorism, piracy, smuggling, and other threats.[22] The deployment is part of a defense and economic deal that Turkey signed with Somalia in February 2024 to reconstruct, equip, and train the Somali Navy in exchange for 30 percent of the revenue from resources found in Somalia’s offshore exclusive economic zone.[23] Turkish naval forces have already been present in the area supporting international efforts to combat piracy since 2009.[24]

Turkey has been a major partner in Somalia since the early 2010s.[25] Turkey established its first African military base in Mogadishu in 2017 to help train and arm the elite Haramcad and Gorgor special force units, which play important roles in the fight against al Shabaab.[26] Between 2011 and 2022, Turkey provided $1 billion in aid for projects in the health and education sectors, municipal services, and infrastructure projects, landing Turkey middle on the list of providers of official direct aid to Somalia.[27] Turkey and Somalia have grown even closer in 2024 with the signing of a gas and oil cooperation deal in Istanbul in March that expands the February 2024 economic-military agreement. The March deal gives the state-owned company Turkish Petroleum exploration and production rights off the coast of Somalia.[28] Somali and Turkish officials have also held at least four high-level meetings in 2024.[29]

Somali forces have minimal naval capabilities, which will make Somalia dependent on Turkish forces and presumably Turkish-supplied assets as part of the cooperation. The Somali Navy has carried out little to no activity since the Somali government reestablished the force in 2009 and has consisted of at most 550 personnel and two dozen light patrol boats.[30] Turkey donated nearly a dozen light patrol boats to the Somali Navy in 2020.[31] Other foreign partners have decided to focus on investing in the capacity of the Somali Police Force’s coast guard department. The EU improved the department’s capacity around Mogadishu by providing communication equipment, radar, a floating jetty, a generator, a headquarters building, and training in 2022.[32]

Somalia likely intends to use its partnership with Turkey to counter Ethiopia’s controversial port agreement with the de facto independent breakaway Somaliland region. Ethiopia signed a memorandum of understanding on January 1 with the de facto independent Somaliland Republic, a breakaway region of Somalia, which will give Ethiopia a naval base on Somaliland’s Red Sea coast in exchange for recognizing Somaliland’s independence.[33] Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed described Red Sea access in July and October 2023 as an existential issue and “natural right” that Ethiopia would fight for if it could not secure it through peaceful means.[34] The memorandum of understanding grants Ethiopia access to a leased military base near the port city of Berbera along Somaliland’s coast on the Gulf of Aden.[35] The port would give Ethiopia access to Red Sea shipping lanes via the Bab al Mandeb strait between Djibouti and Yemen that connects the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

The Somali Federal Government has strongly rejected the deal as a violation of its sovereignty. The SFG rejected the port deal on January 2 as “null and void” for violating Somali sovereignty and international law and threatened to “retaliate” if Ethiopia followed through on the deal.[36] The Somali cabinet labeled the Somaliland-Ethiopia MOU as a “blatant assault” on its sovereignty and said it was an example of Ethiopian “interference against the sovereignty of Somalia.”[37] Somaliland reacted similarly to the Turkey-Somalia agreements that ensued.[38] Somali officials have used similar rhetoric to frame its February defense agreement with Turkey as a measure to protect its sovereignty, indicating it is aimed at the MOU. Somali media initially reported that the February deal would involve Turkey deploying ships to combat illegal activity and remove “any external violations or threats” to Somalia’s coast.[39] However, Somali and Turkish officials maintain that the recent agreements are unrelated to the memorandum between Somaliland and Ethiopia.[40]

The Somalia-Turkey naval agreement is a major economic and geopolitical gain for Turkey that could jeopardize Turkey’s relationship with Ethiopia. The deal will increase Turkish and pro-Turkish naval presence near critical waterways off the Somali coast, such as the Bab el Mandeb Strait, enabling Turkey to increase its geopolitical influence in the broader Horn of Africa-Red Sea region.[41] The Turkish navy is branding the Somali naval deal as another way it can combat piracy, illegal fishing, and other multilateral issues.[42] Turkey’s 30-percent stake in the Somali exclusive economic zone holds significant economic potential if Turkey can help develop Somalia’s “blue economy,” which refers to economic activities in the ocean and coastal areas, including fisheries, aquaculture, tourism, shipping, and offshore oil and gas extraction.[43] Turkey announced that it will send an exploration vessel in September to search for oil and gas off the coast of Somalia to help unlock Somalia’s potential 30 billion barrels of undeveloped offshore gas and oil deposits.[44]

Turkey is working to find a peaceful settlement to the Ethiopia-Somalia dispute to protect its partnership with Ethiopia. A Turkish defense official said in February that its agreement with Somalia aims to combat “illegal and irregular activities in [Somalia’s] territorial waters.”[45] This vague language applies to nonstate threats such as piracy, illegal fishing, and weapon smuggling, which could exempt Turkey from an obligation to confront the Ethiopia-Somaliland port.[46] Turkey is the second-largest foreign investor in Ethiopia and invested $2.5 billion in projects in the country by the end of 2021.[47] Turkey also provided TB2 Bayraktar drones to the Ethiopian government during the Tigray civil war.[48] However, Turkey has previously condemned the port deal as a violation of Somalia’s sovereignty, and Somalia’s interpretation of its defense agreement with Turkey will increase the risks of military confrontation with Ethiopia.[49]

Turkey has also been mediating talks between Somalia and Ethiopia. Turkey hosted discussions between Ethiopia and Somalia in early July.[50] The effort failed to yield a breakthrough, but both sides agreed to hold a second round of talks in Ankara in September.[51] Turkish officials are also separately meeting with Ethiopian officials and will presumably discuss the issue in these meetings. The Ethiopian and Turkish ministers of foreign affairs met in Ethiopia on August 3, 2024.[52] Turkey is also supporting direct negotiations between Somalia and Somaliland, but Somaliland explicitly warned Turkey against deploying naval forces to its maritime zones following the Turkish parliament’s approval of the move in late July.[53]

Turkey’s growing influence in Somalia will also likely shape the Turkish-Emirati rivalry in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have been rivals for over a decade as they competed to expand their regional influence.[54] Both countries see the broader Red Sea area as a crucial strategic theater of competition due to its pivotal geographical position, rich mineral resources, and development potential.[55] A stronger presence near the Red Sea also creates more opportunities for collaboration with other actors with interests in the region, including China, Iran, Russia, and the United States.[56] All four powers have various partners throughout the region to project their power and protect their economic and military interests, given the Red Sea’s strategic importance for maritime traffic.

Turkey’s agreement with Somalia comes at the expense of the UAE. The UAE has competed with Turkey for influence in Somalia through its own bilateral agreements to help train and provide salaries for thousands of Somali soldiers.[57] The partnership had contributed to the SFG’s considering a similar landmark deal with the UAE for over a year before it signed the 2024 deal with Turkey.[58] CTP previously assessed that this setback led the UAE to suspend salary payments and consider broader support cuts to the SFG in March 2024.[59]

The UAE could take steps to counterbalance Turkey’s growing influence in Somalia via its strong ties to Ethiopia and Somaliland. The UAE has invested billions of dollars in Ethiopia since 2018 and sent arms during the Tigray war from 2020–22.[60] It began building an air base in Somaliland but voluntarily scrapped the project in favor of a civilian airport in 2019 when its diminishing role in the Yemeni civil war removed the need for the base.[61] The UAE has also invested nearly half a billion dollars in Somaliland’s Berbera port in exchange for a 30-year concession to manage the port.[62] The Emiratis sought to get Ethiopia partial ownership in the Berbera port in 2019, but Ethiopia failed to make necessary payments on time.[63] The UAE has continued to support Ethiopia’s efforts to gain greater access to the Red Sea with a bilateral maritime agreement in 2023.[64] The UAE helping landlocked Ethiopia gain more access to the Red Sea would reap significant benefits for the UAE given Ethiopia’s economic and political importance in Africa.

Somalia

Al Shabaab carried out its deadliest attack in Mogadishu since October 2022. Five al Shabaab gunmen and a suicide bomber attacked a restaurant near Mogadishu’s Lido beach area on August 2, killing at least 37 people.[65] Al Shabaab claimed responsibility for the attack and said it had targeted Somali officials and officers at a nightclub.[66]

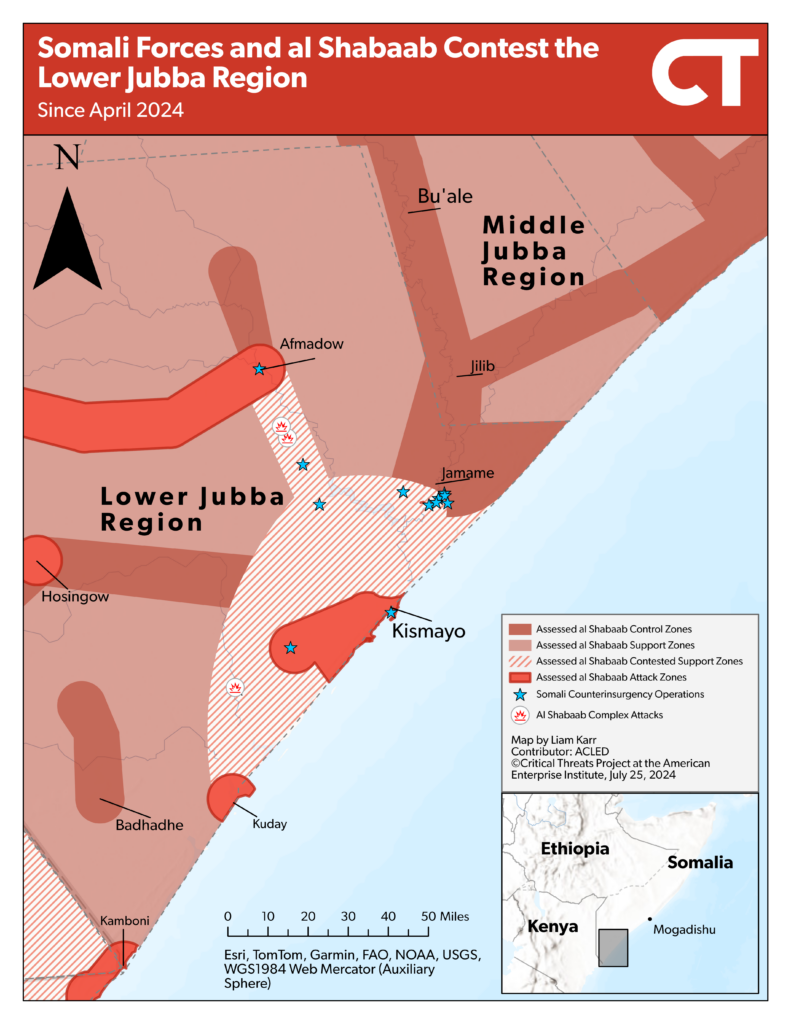

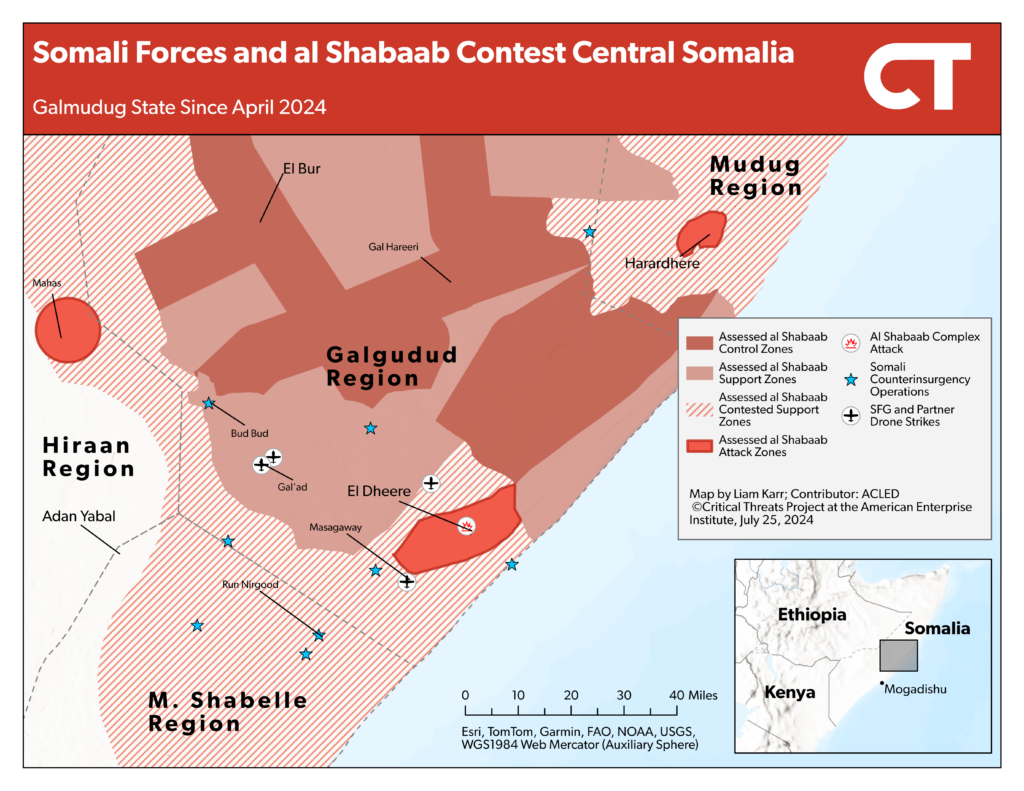

Al Shabaab may have carried out the attack as a response to recent SFG counterinsurgency operations. The SFG escalated counterinsurgency operations against al Shabaab in central and southern Somalia in July 2024. The Somali National Army (SNA) and Jubbaland State Forces launched an offensive in early July in southern Somalia’s Lower Jubba region to strengthen SFG supply lines between government-controlled Kismayo and Afmadow and disrupt al Shabaab’s support zones between its strongholds in the Middle Jubba region and the Badhadhe district.[67] Security forces peacefully secured three crucial towns in southwestern Somalia and subsequently repelled al Shabaab counterattacks on most of the towns in late July.[68] The SFG and allied clan militias in central Somalia also retook the initiative in central Somalia’s Galgudud region in July for the first time since August 2023 and began re-clearing areas that al Shabaab captured in 2023.[69]

Figure 3. Somali Forces and al Shabaab Contest the Lower Jubba Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Figure 4. Somali Forces and al Shabaab Contest Central Somalia

Note: “M. Shabelle” is Middle Shabelle.

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Al Shabaab has previously carried out high-visibility attacks to degrade government and popular morale despite increased counterinsurgency pressure. The group carried out a series of high-visibility suicide bombings between August 2022 and January 2023.[70] That offensive was in response to the SFG’s initial offensive against al Shabaab in central Somalia that began in August 2022.[71] The attacks sought to demonstrate the group’s resiliency and ability to threaten supposedly secure areas despite the pressure it faced from the SFG offensive. The August 2 attack similarly hit a high-traffic area that was supposedly “secure” behind multiple checkpoints.[72] Locals have since organized protests at the beach to demand that the SFG take stronger security measures in the capital.[73]

Figure 5. Al Shabaab Suicide Attacks in Mogadishu During the Second Hassan Sheikh Mohamud Administration